Estimar la incidencia agrupada de la parálisis de Bell después de la vacunación contra el COVID-19.

MétodosRealizamos búsquedas sistemáticas (dos investigadores independientes) en PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Web of Science y Google Scholar. También se realizaron búsquedas en la literatura gris, incluidas las referencias de las referencias y los resúmenes de congresos. Extrajimos datos sobre el número total de participantes, el primer autor, el año de publicación, el país de origen, femenino/masculino, el tipo de vacunas y el número de pacientes que desarrollaron parálisis de Bell después de la vacunación contra el COVID-19.

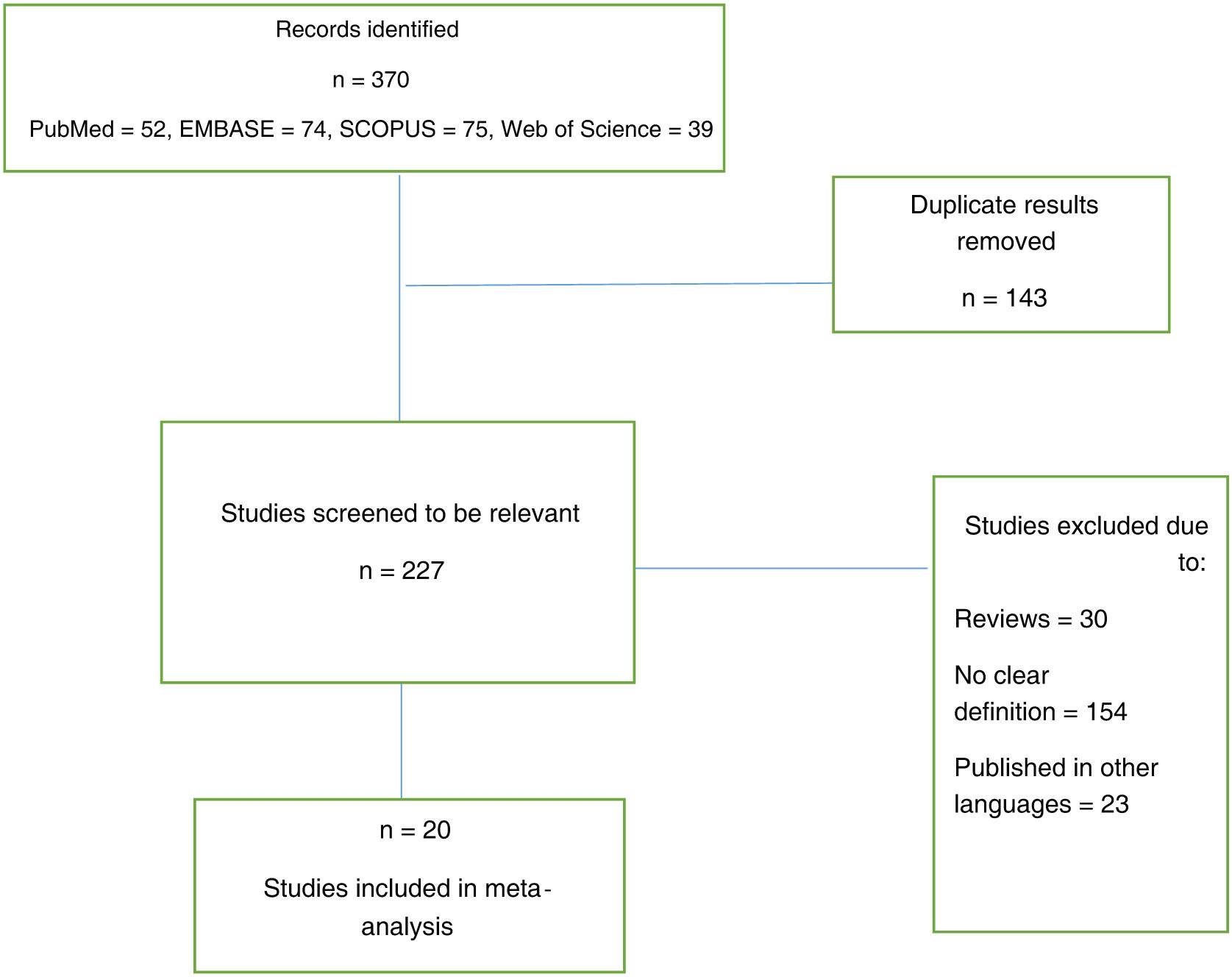

ResultadosLa búsqueda bibliográfica reveló 370 artículos, eliminando posteriormente los duplicados que quedaban 227. Después de una cuidadosa evaluación de los textos completos, quedaron veinte artículos para el metanálisis. Las vacunas más comúnmente administradas fueron Pfizer seguida de Moderna.

En total, 4,54e+07 personas recibieron vacunas contra la COVID-19 y 1739 casos desarrollaron parálisis de Bell. En nueve estudios, se inscribieron controles (individuos sin vacunación). El número total de controles fue de 1809069, de los cuales 203 desarrollaron parálisis de Bell. La incidencia de la parálisis de Bell después de las vacunas COVID-19 fue ignorable. La probabilidad de desarrollar parálisis de Bell después de las vacunas contra la COVID-19 fue de 1,02 (IC 95 %: 0,79-1,32) (I2 = 74,8 %, p < 0,001).

Conclusiónlos resultados de esta revisión sistemática y metanálisis muestran que la incidencia de parálisis facial periférica después de la vacunación contra el COVID-19 es despreciable y que la vacunación no aumenta el riesgo de desarrollar parálisis de Bell. Tal vez, la parálisis de Bell es un síntoma de presentación de una forma más grave de COVID-19, por lo que los médicos deben ser conscientes de esto.

To estimate the pooled incidence of Bell’s palsy after COVID-19 vaccination.

MethodsPubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched by 2 independent researchers. We also searched the grey literature including references of the references and conference abstracts. We extracted data regarding the total number of participants, first author, publication year, the country of origin, sex, type of vaccines, and the number of patients who developed Bell’s palsy after COVID-19 vaccination.

ResultsThe literature search revealed 370 articles, subsequently deleting duplicates 227 remained. After careful evaluation of the full texts, 20 articles remained for meta-analysis. The most commonly administered vaccines were Pfizer followed by Moderna.

In total, 4.54e+07 individuals received vaccines against COVID-19, and 1739 cases developed Bell’s palsy. In nine studies, controls (individuals without vaccination) were enrolled. The total number of controls was 1 809 069, of whom 203 developed Bell’s palsy. The incidence of Bell’s palsy after COVID-19 vaccines was ignorable. The odds of developing Bell’s palsy after COVID-19 vaccines was 1.02 (95% CI: 0.79-1.32) (I2 = 74.8%, P < .001).

ConclusionThe results of this systematic review and meta-analysis show that the incidence of peripheral facial palsy after COVID-19 vaccination is ignorable and vaccination does not increase the risk of developing Bell’s palsy. Maybe, Bell’s palsy is a presenting symptom of a more severe form of COVID-19, so clinicians must be aware of this.

In December 2019, a new coronavirus was detected in Wuhan, China which spread rapidly all over the world.1 It is in the pandemic stage and different vaccines have been developed to stop the pandemic.2 The European Medicines Agency, the US Food and Drug Administration, and the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency have approved various types of vaccines since December 2020.2 Each vaccine has its safety and efficacy profiles which raises the necessity for careful evaluation. The side effects have a wide range from injection site pain (swelling) to extreme reactions such as anaphylaxis.3,4 Neurological complications have been reported after COVID-19 vaccination including Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS), neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD), transverse myelitis, multiple sclerosis (MS), thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome, and Bell’s palsy.5–10

Bell’s palsy is acute peripheral facial nerve with unknown aetiology and sudden onset of unilateral peripheral facial paralysis.10 It is transient and more than half of the affected patients recover within 6 months without treatment.11 The relationship between vaccination and incidence of Bell’s palsy is unclear while mimicry of host molecules by the vaccinal antigen could be the possible explanation.12 Up to now, different studies reported various incidence rates of Bell’s palsy after vaccination with different vaccines.13–16 So, we designed this systematic review and meta-analysis to estimate the pooled incidence of Bell’s palsy after COVID-19 vaccination.

MethodsPubMed, Scopus, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched by 2 independent researchers. We also searched the grey literature including references of the references and conference abstracts by 10th February 2022.

After deleting duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of the potential studies and in the case of discrepancy, they asked the third one to solve the disagreement.

Then the full texts of the remained studies were assessed and the data were extracted. The extracted data were entered in a datasheet and the third one checked the data of two sources.

We extracted data regarding the total number of participants, first author, publication year, the country of origin, sex, type of vaccines, and the number of patients who developed Bell’s palsy after COVID-19 vaccination.

The MeSH terms which were used for searching in the PubMed are attached in a supplementary file.

Inclusion criteria were: retrospective/prospective cohort studies which reported incidence of facial palsy after vaccination, articles published in English.

Exclusion criteria were: Letters to the editor, case-control, case reports, and cross-sectional studies which had no clear data.

Risk of bias assessment: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (adapted for cohort studies).17

Statistical analysisAll statistical analyses were performed using STATA (Version 14.0; Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA.

To determine heterogeneity, inconsistency (I2) was calculated.

We used random-effects model for meta-analysis as the heterogeneity between study results (I2) was more than 50%.

ResultsThe literature search revealed 370 articles, subsequently after deleting duplicates 227 remained. After careful evaluation of the full texts, 20 articles remained for meta-analysis (Fig. 1).

The most commonly administered vaccines were Pfizer (in 16 studies [80%]) followed by Moderna (4 [25%]).

In total, 4.54e+07 individuals received vaccines against COVID-19, and 1739 cases developed Bell’s palsy

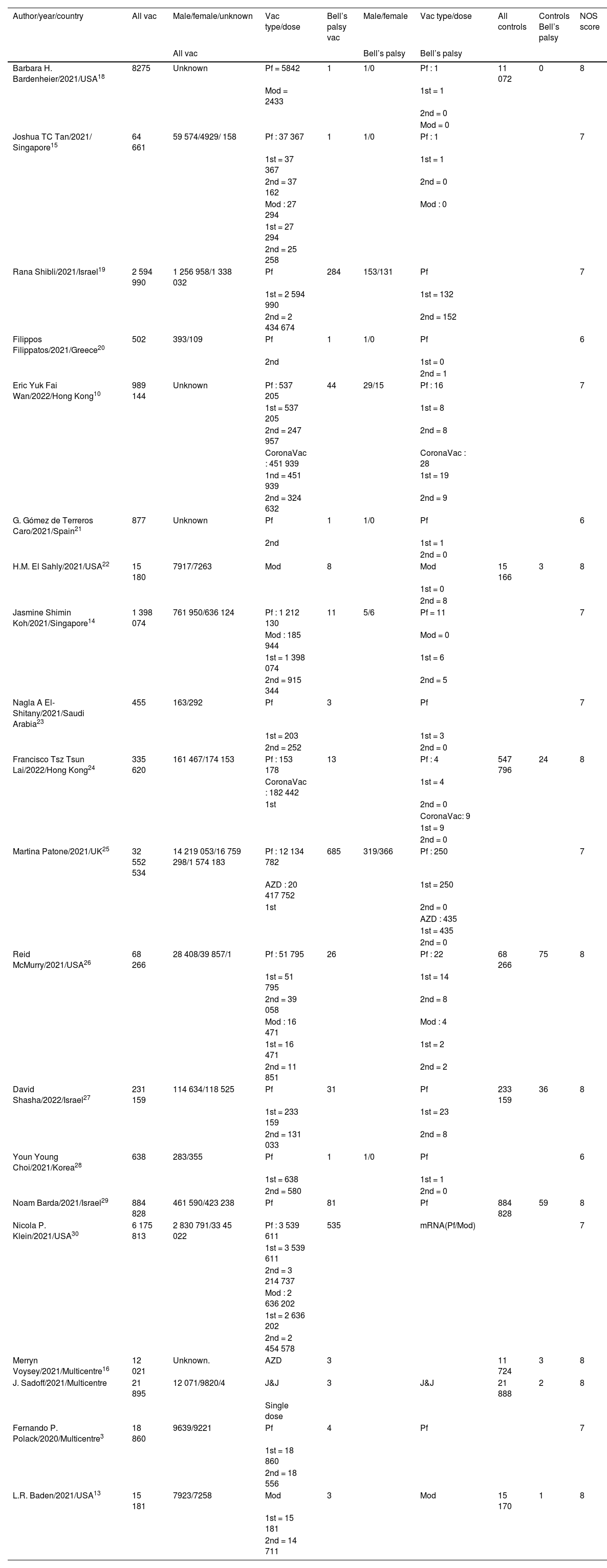

Totally 1.79e+07 patients received Pfizer vaccines and 429 cases developed Bell’s palsy. In 12 studies, it was determined the dose of the vaccines (first or second). In 9 studies, controls (individuals without vaccination) were enrolled. The total number of controls was 1 809 069, of whom203 developed Bell’s palsy. The quality assessment scores of included studies ranged between 6 and 8 (Table 1).

Basic characteristics of included studies.

| Author/year/country | All vac | Male/female/unknown | Vac type/dose | Bell’s palsy vac | Male/female | Vac type/dose | All controls | Controls Bell’s palsy | NOS score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All vac | Bell’s palsy | Bell’s palsy | |||||||

| Barbara H. Bardenheier/2021/USA18 | 8275 | Unknown | Pf = 5842 | 1 | 1/0 | Pf : 1 | 11 072 | 0 | 8 |

| Mod = 2433 | 1st = 1 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 0 | |||||||||

| Mod = 0 | |||||||||

| Joshua TC Tan/2021/ Singapore15 | 64 661 | 59 574/4929/ 158 | Pf : 37 367 | 1 | 1/0 | Pf : 1 | 7 | ||

| 1st = 37 367 | 1st = 1 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 37 162 | 2nd = 0 | ||||||||

| Mod : 27 294 | Mod : 0 | ||||||||

| 1st = 27 294 | |||||||||

| 2nd = 25 258 | |||||||||

| Rana Shibli/2021/Israel19 | 2 594 990 | 1 256 958/1 338 032 | Pf | 284 | 153/131 | Pf | 7 | ||

| 1st = 2 594 990 | 1st = 132 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 2 434 674 | 2nd = 152 | ||||||||

| Filippos Filippatos/2021/Greece20 | 502 | 393/109 | Pf | 1 | 1/0 | Pf | 6 | ||

| 2nd | 1st = 0 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 1 | |||||||||

| Eric Yuk Fai Wan/2022/Hong Kong10 | 989 144 | Unknown | Pf : 537 205 | 44 | 29/15 | Pf : 16 | 7 | ||

| 1st = 537 205 | 1st = 8 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 247 957 | 2nd = 8 | ||||||||

| CoronaVac : 451 939 | CoronaVac : 28 | ||||||||

| 1nd = 451 939 | 1st = 19 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 324 632 | 2nd = 9 | ||||||||

| G. Gómez de Terreros Caro/2021/Spain21 | 877 | Unknown | Pf | 1 | 1/0 | Pf | 6 | ||

| 2nd | 1st = 1 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 0 | |||||||||

| H.M. El Sahly/2021/USA22 | 15 180 | 7917/7263 | Mod | 8 | Mod | 15 166 | 3 | 8 | |

| 1st = 0 | |||||||||

| 2nd = 8 | |||||||||

| Jasmine Shimin Koh/2021/Singapore14 | 1 398 074 | 761 950/636 124 | Pf : 1 212 130 | 11 | 5/6 | Pf = 11 | 7 | ||

| Mod : 185 944 | Mod = 0 | ||||||||

| 1st = 1 398 074 | 1st = 6 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 915 344 | 2nd = 5 | ||||||||

| Nagla A El-Shitany/2021/Saudi Arabia23 | 455 | 163/292 | Pf | 3 | Pf | 7 | |||

| 1st = 203 | 1st = 3 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 252 | 2nd = 0 | ||||||||

| Francisco Tsz Tsun Lai/2022/Hong Kong24 | 335 620 | 161 467/174 153 | Pf : 153 178 | 13 | Pf : 4 | 547 796 | 24 | 8 | |

| CoronaVac : 182 442 | 1st = 4 | ||||||||

| 1st | 2nd = 0 | ||||||||

| CoronaVac: 9 | |||||||||

| 1st = 9 | |||||||||

| 2nd = 0 | |||||||||

| Martina Patone/2021/UK25 | 32 552 534 | 14 219 053/16 759 298/1 574 183 | Pf : 12 134 782 | 685 | 319/366 | Pf : 250 | 7 | ||

| AZD : 20 417 752 | 1st = 250 | ||||||||

| 1st | 2nd = 0 | ||||||||

| AZD : 435 | |||||||||

| 1st = 435 | |||||||||

| 2nd = 0 | |||||||||

| Reid McMurry/2021/USA26 | 68 266 | 28 408/39 857/1 | Pf : 51 795 | 26 | Pf : 22 | 68 266 | 75 | 8 | |

| 1st = 51 795 | 1st = 14 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 39 058 | 2nd = 8 | ||||||||

| Mod : 16 471 | Mod : 4 | ||||||||

| 1st = 16 471 | 1st = 2 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 11 851 | 2nd = 2 | ||||||||

| David Shasha/2022/Israel27 | 231 159 | 114 634/118 525 | Pf | 31 | Pf | 233 159 | 36 | 8 | |

| 1st = 233 159 | 1st = 23 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 131 033 | 2nd = 8 | ||||||||

| Youn Young Choi/2021/Korea28 | 638 | 283/355 | Pf | 1 | 1/0 | Pf | 6 | ||

| 1st = 638 | 1st = 1 | ||||||||

| 2nd = 580 | 2nd = 0 | ||||||||

| Noam Barda/2021/Israel29 | 884 828 | 461 590/423 238 | Pf | 81 | Pf | 884 828 | 59 | 8 | |

| Nicola P. Klein/2021/USA30 | 6 175 813 | 2 830 791/33 45 022 | Pf : 3 539 611 | 535 | mRNA(Pf/Mod) | 7 | |||

| 1st = 3 539 611 | |||||||||

| 2nd = 3 214 737 | |||||||||

| Mod : 2 636 202 | |||||||||

| 1st = 2 636 202 | |||||||||

| 2nd = 2 454 578 | |||||||||

| Merryn Voysey/2021/Multicentre16 | 12 021 | Unknown. | AZD | 3 | 11 724 | 3 | 8 | ||

| J. Sadoff/2021/Multicentre | 21 895 | 12 071/9820/4 | J&J | 3 | J&J | 21 888 | 2 | 8 | |

| Single dose | |||||||||

| Fernando P. Polack/2020/Multicentre3 | 18 860 | 9639/9221 | Pf | 4 | Pf | 7 | |||

| 1st = 18 860 | |||||||||

| 2nd = 18 556 | |||||||||

| L.R. Baden/2021/USA13 | 15 181 | 7923/7258 | Mod | 3 | Mod | 15 170 | 1 | 8 | |

| 1st = 15 181 | |||||||||

| 2nd = 14 711 |

Pf = Pfizer, Mod = Moderna, AZD = AstraZeneca.

UK: United Kingdom.

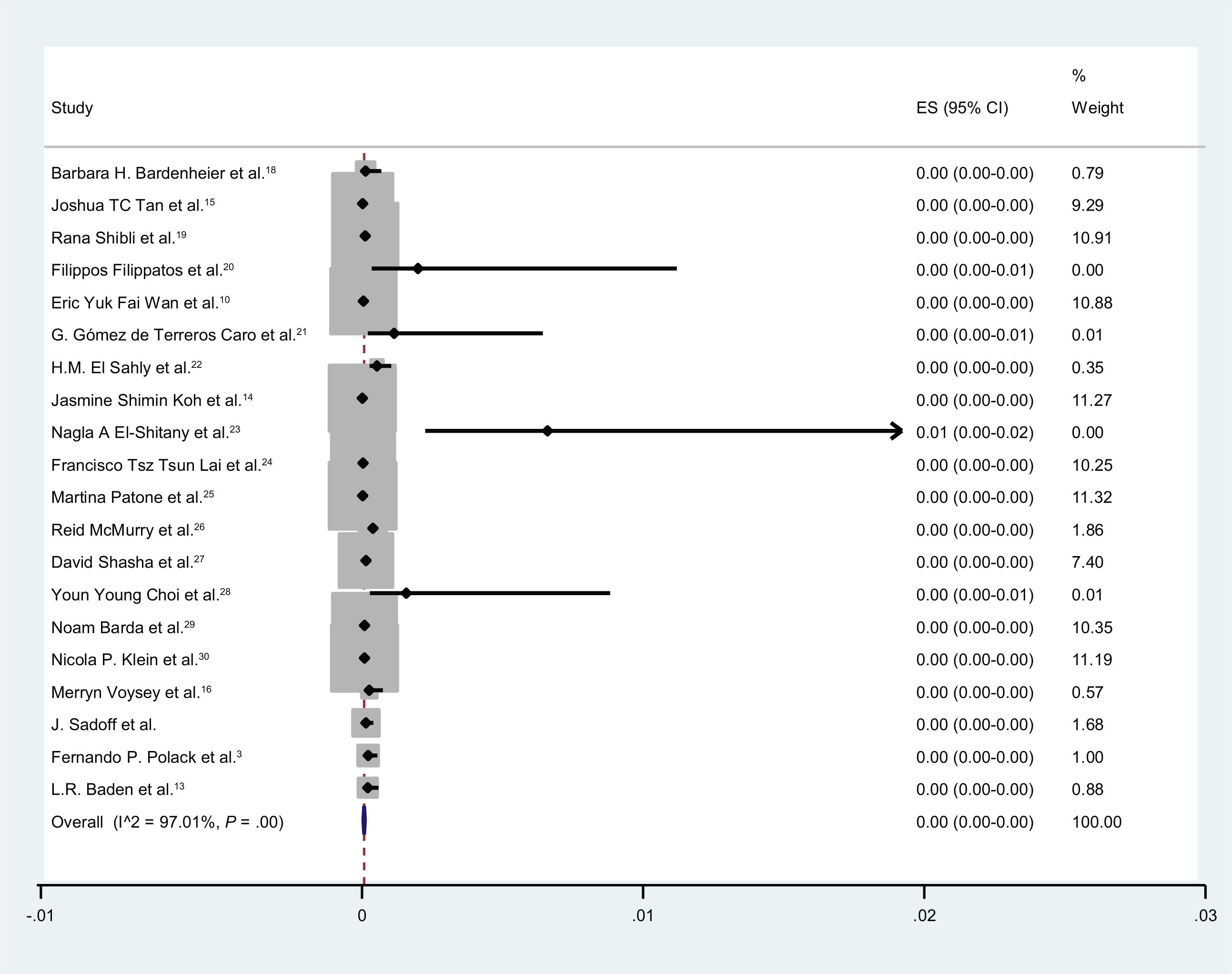

The incidence of Bell’s palsy after COVID-19 vaccines was ignorable (Fig. 2).

The incidence of Bell’s palsy after COVID-19 vaccines was ignorable (Fig. 2).

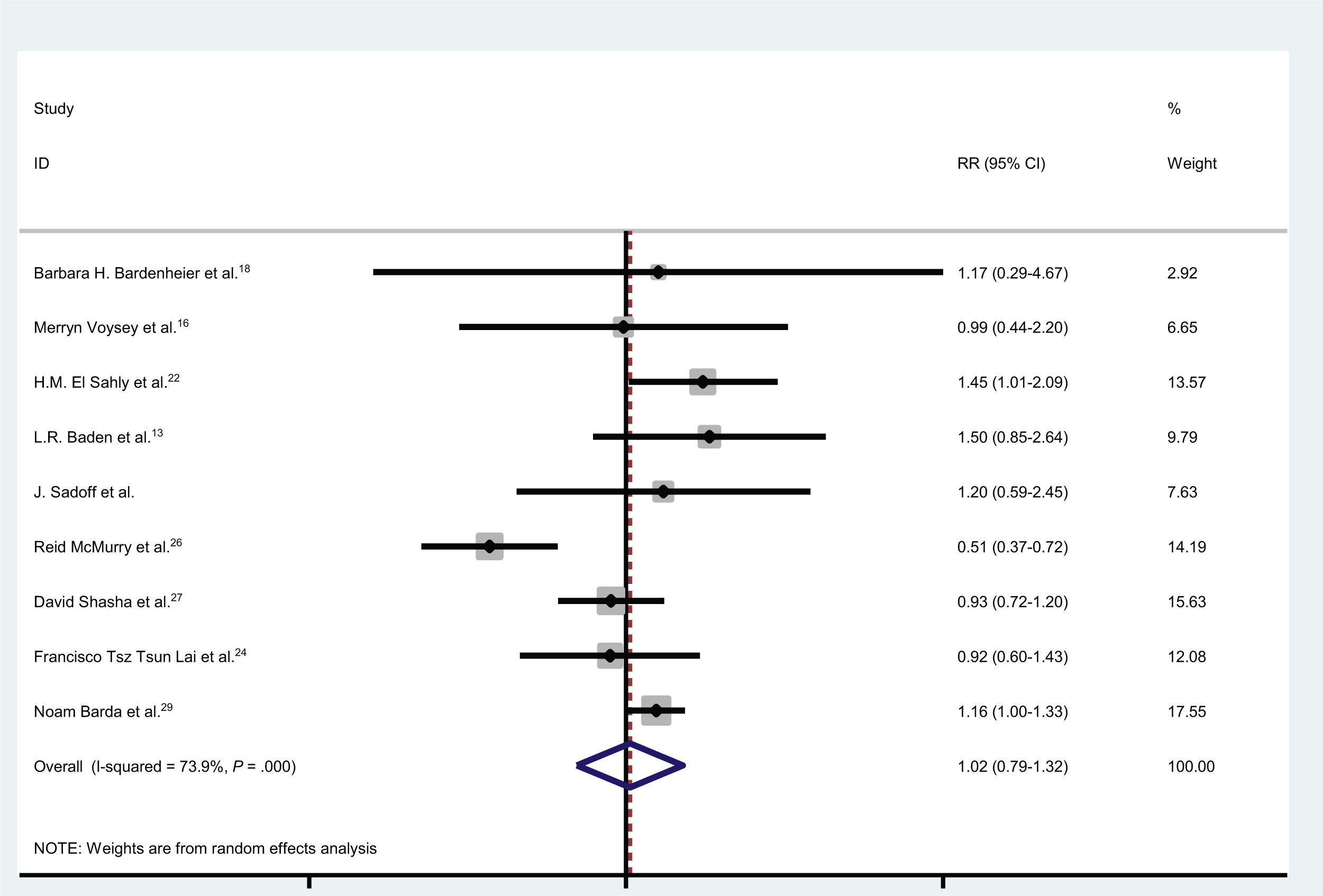

The odds of developing Bell’s palsy after COVID-19 vaccines was 1.02 (95% CI: 0.79-1.32) (I2 = 74.8%, P <0.001) (Fig. 3) (only 9 studies had controls).

DiscussionTo our knowledge, this is the first systematic review and meta-analysis estimating the pooled incidence of Bell’s palsy after COVID-19 vaccines. The results show that the pooled incidence is ignorable and administration of the COVID-19 vaccines does not increase the risk of developing Bell’s palsy.

In a multi-centric study in the USA which was conducted by Baden et al.,13 15 181 individuals who received Moderna vaccine and 15 170 controls were evaluated. Their results show that 3 individuals in the vaccinated group and one in the control group developed Bell’s palsy.13 The odds of developing Bell’s palsy in their study was 1.5, which was not significant (95% CI: 0.85-2.6).

McMurry et al.26 enrolled 68 266 vaccinated individuals and 68 266 controls. In their study, the incidence of Bell’s palsy was higher among controls which suggested that administration of COVID-19 vaccines decreases the risk of Bell’s palsy (OR = 0.51, 95% CI: 0.37-0.72).26

In another large study which was conducted in Israel, Barda et al.29 recruited 884 828 vaccinated and the same number of controls. The incidence of Bell’s palsy was higher in the vaccinated group while there was no significant association between Bell’s palsy and COVID-19 vaccination.29

Association between vaccination and Bell’s palsy occurrence had been reported previously. Strong associations were reported between the intranasal inactivated influenza vaccine and also influenza H1N1 monovalent vaccine.31,32 The aetiology of Bell’s palsy after vaccination is not fully understood while there are some hypotheses that re-activation of a herpes virus infection, mimicry of host molecules, or activation of dormant auto-reactive T cells play a role.12 As the results of this systematic review show, there is no association between COVID-19 vaccination and Bell’s palsy.

A new study shows that the incidence of neurological adverse effects after COVID-19 infection is higher than rates of neurological complications after vaccination, besides serious neurological adverse effects are rare.33

In all included studies in this systematic review, Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca vaccines were used. Pfizer and Moderna are mRNA vaccines while the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is an adenoviral (ChAdOx1) vector-based COVID-19 vaccine with a wide range of complications including thrombosis with thrombocytopenia syndrome, transverse myelitis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, etc.34–36 In only two included studies AstraZeneca was administered which showed no significant association between vaccination and Bell’s palsy.

This study had some strengths. First, it is the first systematic review and meta-analysis in this field. Second, we estimated the odds of developing Bell’s palsy after vaccination.

ConclusionThe results of this systematic review and meta-analysis show that the incidence of peripheral facial palsy after COVID-19 vaccination is ignorable and vaccination does not increase the risk of developing Bell’s palsy. Maybe, Bell’s palsy is a presenting symptom of a more severe form of COVID-19, so clinicians must be aware of this.