Hereditary ataxia (HA) and hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) are rare diseases; as such, they are rarely managed in general neurology consultations. We present a set of brief, practical recommendations for the diagnosis and management of these patients, as well as a standardised procedure for comprehensive evaluation of disability. We provide definitions for HA and “HA plus,” and “pure” and “complicated” HSP; describe the clinical assessment of these patients, indicating the main complementary tests and clinical scales for physical and psychological assessment of the patients; and summarise the available treatments. These recommendations are intended to facilitate daily neurological practice and to unify clinical criteria and disability assessment protocols for patients with HA and HSP.

Las ataxias hereditarias (AH) y paraparesias espásticas hereditarias (PEH) son enfermedades raras, poco frecuentes en las consultas del neurólogo general. Proponemos una guía práctica y breve de diagnóstico y manejo de estos pacientes, así como un procedimiento para la evaluación integrada del grado de su discapacidad. Se describen por apartados los conceptos y definiciones de AH y AH-plus y PEH pura y complicada, la valoración clínica de los pacientes con las principales pruebas complementarias a realizar, las escalas clínicas necesarias para poder graduar la condición física y psíquica de los pacientes, y se resumen los tratamientos disponibles. Esta guía pretende facilitar la asistencia clínica diaria por parte del neurólogo y unificar los criterios médicos y la metodología de evaluación de la discapacidad de los pacientes con AH y paraparesias espásticas hereditarias.

Rare diseases are defined as diseases that affect a limited number of individuals in a given population. In Spain and in Europe, rare diseases are classed as those affecting less than 1 individual per 2000 population (general prevalence of 6%-8% patients worldwide).

Over 7000 rare diseases have been described, many of which affect the nervous system. Up to 65% of these conditions cause a high level of physical or intellectual disability, greatly limiting independence.

Hereditary ataxia (HA) and hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) are neurodegenerative syndromes with a highly heterogeneous genetic basis. Their prevalence is unknown, but is estimated at 3-20 cases per 100 000 population for HA and 1.2-9.6 cases per 100 000 population for HSP. HA and HSP may affect individuals of any age and sex, but are more common in young adults.

A recent epidemiological study estimated the prevalence of HA and HSP between 2018 and 2019 in Spain.1 That study estimated prevalence rates of HA and HSP in Spain at 5.48 and 2.24 cases per 100 000 population, respectively. The most frequent type of dominant HA is SCA3, followed by SCA2, while the most frequent types of recessive HA are Friedreich ataxia and Niemann-Pick disease type C. The most frequent type of dominant HSP is SPG4, and the most frequent recessive type is SPG7, followed by SPG11. Genetic diagnosis was unavailable in 47.6% of cases included in the study by Ortega Suero et al.1

The recently enacted Spanish law on disability (Law 8/2021 of 2 June, Spanish Official State Gazette [BOE] of 3 June) stipulates a series of amendments to previously enacted laws to increase the support offered to people with disability.2 HA and HSP are very infrequent at general neurology departments and other specialist consultations involved in the assessment of disability in these patients (primary care, internal medicine, physical medicine and rehabilitation, occupational medicine, occupational health departments, medical experts, etc).3,4

The purpose of these practical recommendations is to assist neurologists and other specialists in the diagnosis of HA and HSP and the assessment of the associated disability, and to facilitate patient access to the necessary social and legal resources.

MethodsWe conducted a literature search on PubMed, Cochrane Library Plus, Clinical Keys, MESH, and MEDLINE to identify articles published between 1980 and 2021. We also evaluated the most frequently published clinical practice guidelines and consensus documents.

This brief set of guidelines aims to assist in the diagnosis of HA and HSP and the clinical assessment of these patients’ physical and mental status. To this end, we provide definitions for HA and HSP and select the validated scales most widely used in clinical practice. We also provide a series of tables and flowcharts that facilitate diagnosis of HA and HSP and comprehensive assessment of the associated disability, which is the main purpose of this document.

A wide range of classifications for HA and HSP have been published, based on the genetic pattern, type of onset, age of onset, complementary test findings, etc; these assist in selecting the most appropriate genetic test. Furthermore, several validated scales are available that provide additional information about these patients’ physical and mental status. A review of these resources is beyond the scope of these brief, practical clinical practice guidelines, but further information may be consulted at the website of the Spanish Society of Neurology: “Guidelines for the diagnosis and assessment of disability of patients with hereditary ataxia and hereditary spastic paraplegia” (https://www.sen.es/profesionales/guias-y-protocolos; document in Spanish).

ResultsDefinitionsAtaxia: a disorder of coordination due to damage to the cerebellum or its connections.

Ataxia plus: a disorder that combines ataxia with clinical manifestations of damage to other structures of the nervous system or to other body systems (optic atrophy, retinal degeneration, oculomotor dysfunction, epilepsy, myoclonus, pyramidal signs, signs of polyneuropathy, multisystem involvement, etc).

Hereditary spastic paraplegia: a heterogeneous group of genetic diseases characterised by bilateral lower limb spasticity and weakness, which cause difficulty walking (pyramidal signs ± sphincter dysfunction ± reduced vibration sensitivity in the distal lower limbs).

Hereditary spastic paraplegia plus: a disorder that combines HSP with such other clinical manifestations as ataxia, myoclonic epilepsy, seizures, extrapyramidal signs, oculomotor dysfunction, etc.

Medical historyA complete medical history should be gathered in all cases of suspected ataxia, including data on family history of ataxia, parental consanguinity, pregnancy and delivery, psychomotor development, gait or balance disorders, instability, speech alterations (dysarthria), oculomotor dysfunction (eg, diplopia, oscillopsia), limb rigidity, and stumbling.5–7

Information must also be gathered on the form of disease onset (acute, subacute, chronic) and progression (slowly progressive, rapidly progressive, episodic, stable), as well as on trigger and exacerbating factors, with a view to differentiating hereditary ataxias from acquired forms (Tables 1 and 2). Other manifestations to consider include urinary urgency or incontinence, paraesthesia, muscle spasms and pain in the lower limbs, and psychiatric or systemic alterations. Consumption of alcohol and toxic substances and use of other pharmacological treatments also constitute relevant information.

Classification of primary ataxias by Klockgether (2005).

| Hereditary ataxia | Non-hereditary ataxia |

|---|---|

| Autosomal dominant (SCA) | Cerebellar-type multiple system atrophy |

| Autosomal recessive (ARCA) | Idiopathic late-onset cerebellar ataxia |

| X-linked cerebellar ataxias | Symptomatic ataxias (alcoholic cerebellar degeneration, other toxic causes, paraneoplastic, vitamin deficiency, acquired metabolic disorders, autoimmune cerebellar encephalitis) |

| Episodic |

Classification of secondary or acquired ataxias.

| INFECTIOUS |

| - Cerebellitis |

| - Epstein-Barr virus |

| - Post-infectious encephalitis |

| - Bickerstaff encephalitis |

| - Human immunodeficiency virus |

| - Whipple disease |

| - Mycoplasma pneumoniae |

| - Meningitis |

| PRION DISEASES |

| - Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease |

| - Gerstmann-Sträussler-Scheinker disease |

| TOXIC |

| - Alcohol |

| - Antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin) |

| - Hg, Mn, Bi, Pb |

| - Chemotherapy drugs (5-FU, cytosine arabinoside) |

| - Lithium |

| - Solvents (toluene) |

| - Siderosis |

| - Wilson disease |

| METABOLIC |

| - Vitamin B1/B12/E deficiency |

| ENDOCRINE DISORDERS |

| - Hypothyroidism |

| - Hypoparathyroidism |

| VASCULAR DISEASES |

| - Vertebrobasilar stroke |

| - Haemorrhage |

| - Arteriovenous malformations |

| TUMOURS |

| - Posterior fossa tumours |

| - Meningeal carcinomatosis |

| PAROXYSMAL |

| - Epilepsy |

| - Migraine |

| - Fever |

| - Heat stroke |

The examination should target the cerebellum, motor system, and cognition and mood (Fig. 1). The patient’s clinical history should include specific sections for this information.

Standardised scales for disability assessmentThe most widely used scales for disability assessment, both in clinical practice and in the research setting, are the following7–20:

- -

Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia (SARA)

- -

Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale (FARS)

- -

Inventory of Non-Ataxia Signs (INAS) for systematic phenotyping, with modifications (eg, bradykinesia, ptosis, head impulse test)

- -

Spastic Paraplegia Rating Scale (SPRS)

- -

Activities of Daily Living (ADL)

- -

Questionnaires for depression and quality of life (EQ-5D/EQ-5D-Y and PHQ-9)

- -

Disease severity index for autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay (disease-specific outcome measure).

All these instruments are complex and take over 15 minutes to complete. The most widely used in clinical practice are the SARA7 and the SPRS17; at least these 2 should be administered to patients with disability.

Complementary testsPatients should ideally complete certain basic complementary tests that are available at most primary care centres and hospitals: head and neck MRI; electromyoneurography; visual, somatosensory, and/or auditory evoked potentials; ophthalmological, cardiological, and otorhinolaryngological assessment; and laboratory tests (Fig. 2).5,20–23

Metabolic and hormonal studies may analyse a wide range of parameters, but in general terms, the laboratory parameters that should be measured in all cases are:

- -

Electrolytes, CPK, albumin, complete blood count with a blood smear for detecting acanthocytes, ALT, GGT, alkaline phosphatase

- -

TSH, T3, T4

- -

Vitamins A, B1, B12, D, E, and K; alpha-fetoprotein; immunoglobulins; angiotensin-converting enzyme; homocysteine; copper; ceruloplasmin; albumin

- -

Antineuronal, anti-GAD, antinuclear, antiphospholipid, antiganglioside, anti-TG2, and antiendomysium antibodies.

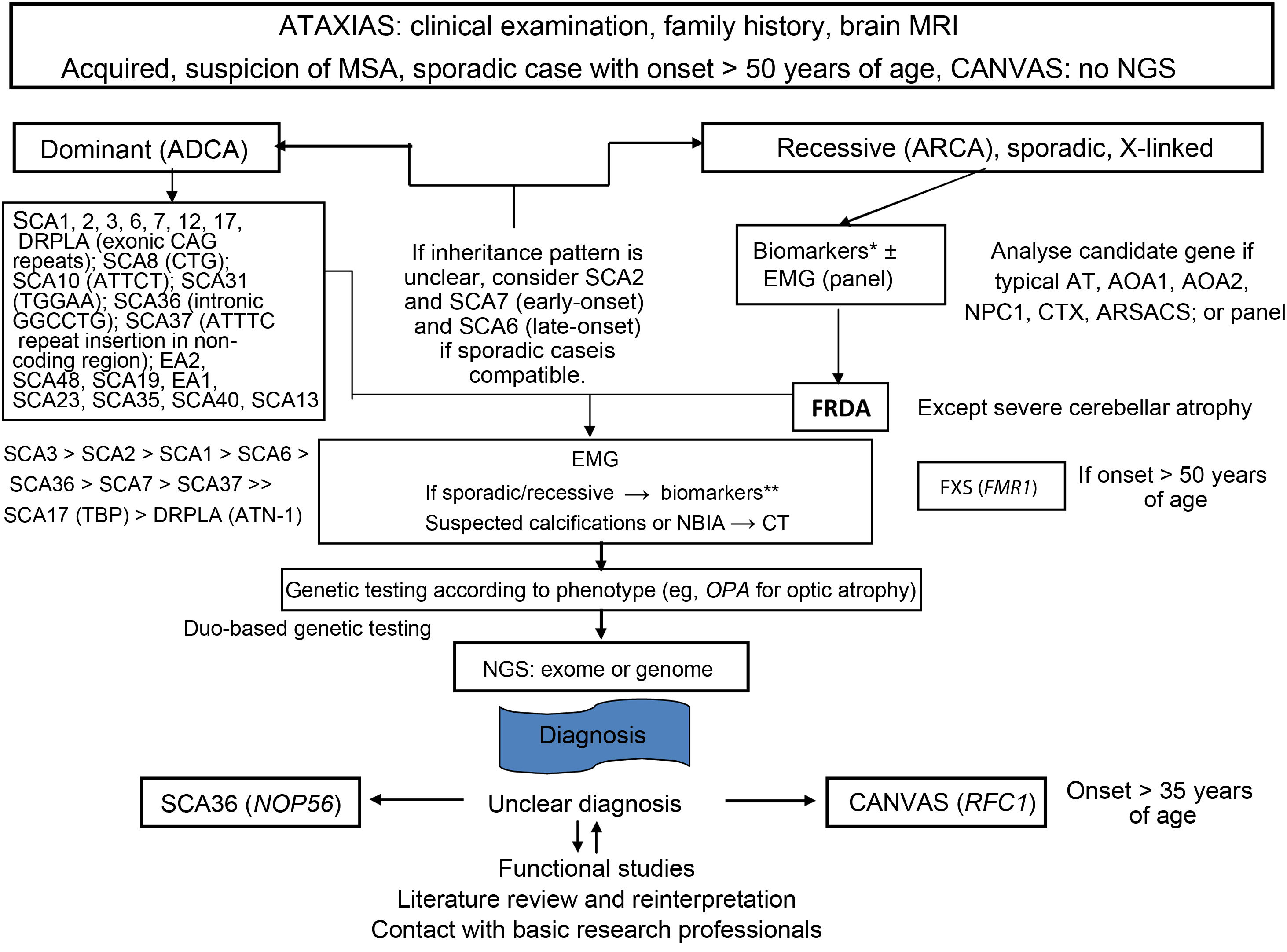

Finally, a molecular genetic study should be performed to determine the type of HA or HSP, where possible. There exist autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked, and mitochondrial forms of both HA and HSP. The specific genetic studies used will depend on the suspected diagnosis and availability at each centre and in each autonomous community (Figs. 3–5).5,20–22,24,25 However, despite a rigorous diagnostic process, 40%-50% of patients will not receive a definitive diagnosis.1

Flow diagram showing the genetic diagnosis process of ataxia. Modified from Angelini et al.,4 with permission.

AOA1: ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 1; AOA2: ataxia with oculomotor apraxia type 2; ARSACS: autosomal recessive spastic ataxia of Charlevoix-Saguenay; AT: ataxia telangiectasia; ATN-1: atrophin 1; CAG: cytosine-adenine-guanine trinucleotide; CANVAS: cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy and vestibular areflexia syndrome; CT: computed tomography; CTX: cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis; DRPLA: dentatorubral-pallidoluysian atrophy; EA: episodic ataxia; EMG: electromyography; FRDA: Friedreich ataxia; FMR1: fragile X mental retardation 1 gene; FXS: fragile X syndrome; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; MSA: multiple system atrophy; NBIA; neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation; NGS: next-generation sequencing; NOP56: nucleolar protein 56; SCA36: spinocerebellar ataxia 36; NPC1: Niemann-Pick disease type C1; OPA: optic atrophy; RFC1: replication factor C subunit 1; SCA: spinocerebellar ataxia; SCA17: spinocerebellar ataxia 17; TBP: TATA-binding protein.

*Vitamin E, copper, ceruloplasmin, alpha-fetoprotein, albumin, hexosaminidases, phytanic acid, pristanic acid, very–long-chain fatty acids, homocysteine, cholesterol, cholestanol, lyso-SM-509, creatine phosphokinase, gonadotropins, acanthocytes, Glut1 (METAglut1).

**(Under fasting conditions:) lactate, pyruvate, plasma amino acids by chromatography, urinary organic acids by chromatography, coenzyme Q10.

Flow diagram showing the genetic diagnosis process of hereditary spastic paraplegia. Modified from Angelini et al.,4 with permission.

ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; CP: cerebral palsy; EMG: electromyography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PLS: primary lateral sclerosis.

*Metabolic disorders: methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase deficiency and hyperhomocysteinaemia (type III homocystinuria); methylmalonic acid and orotic acid in urine; pyrimidines in urine; total plasma homocysteine (cobalamin C disease); plasma ammonia (urea cycle disorders); biotinidase; phenylketonuria; hyperglycinaemia (glycine encephalopathy); folate; urinary carnosinase (homocarnosinosis); lactate; aconitase, very–long-chain fatty acids (adrenomyeloneuropathy); cholesterol and triglycerides; cholestanol (cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis); amino acids (citrulline, proline, ornithine, arginine, lysine, cysteine); gonadotropins; manganese; amino acids, ribitol, and d-arabitol in the cerebrospinal fluid; and nutrition disorders (copper, vitamin B12, vitamin E, β-tocopherol).

Comprehensive assessment of hereditary ataxias and spastic paraplegias.

EQ-5D: EuroQol 5 Dimensions; FARS: Friedreich Ataxia Rating Scale; IADL: Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; INAS: Inventory of Non-Ataxia Signs; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire; SARA: Scale for the Assessment and Rating of Ataxia; SPRS: Spastic Paraplegia Rating Scale.

In the event of strong clinical suspicion, patients for whom this basic set of diagnostic tests is unable to provide diagnostic certainty may also be transferred to one of the 7 reference centres for hereditary ataxias and spastic paraplegias currently operating in Spain: Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla (Cantabria), Hospital Universitari Vall d’Hebron (Catalonia), Hospital Clinic de Barcelona (Catalonia), Hospital Sant Joan de Deu (Catalonia), Hospital Universitario La Paz (Madrid), Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal (Madrid), and Hospital Universitario y Politécnico La Fe (Valencia).

Treatment and prognosisAetiological treatments are available for some types of HA and HSP; identifying the disease type is therefore essential (Table 3).20,23,26

Types of hereditary ataxia and hereditary spastic paraplegia for which specific treatments are available.

| Cerebellar ataxia and coenzyme Q10 deficiency (SCAR9, SCAR10, mutations in COQ2, PDSS2, COQ4, COQ5, and COQ9) | High doses of coenzyme Q10 |

| Cerebrotendinous xantomatosis | Chenodeoxycholic acid and statins |

| Vitamin E deficiency (abetalipoproteinaemia, hypobetalipoproteinaemia, ataxia with vitamin E deficiency) | High doses of vitamin E |

| Biotinidase deficiency | Biotin supplementation |

| Hartnup disease | Nicotinamide supplementation |

| Hyperammonaemia and urea cycle disorders | Low-protein and low-arginine diet; ornithine and citrulline supplementation; sodium phenylbutyrate |

| Maple syrup urine disease | Dietary protein restriction, thiamine supplementation |

| Refsum disease | Diet low in phytanic acid, plasmapheresis |

| Niemann-Pick disease type C1 | Miglustat |

| Wilson disease | Penicillamine and other chelating agents, zinc supplementation |

However, most types of HA and HSP are characterised by progressive functional disability. Efforts should be made to preserve the patient’s functional status with such rehabilitation therapies as physical therapy, speech therapy, and occupational therapy. The need for orthotic devices and such aids as canes, walkers, and wheelchairs, should also be considered. Determining the degree of disability helps to identify patient needs and to adapt the available resources.

Furthermore, symptomatic pharmacological treatment with botulinum toxin infiltrations or oral or intrathecal drugs (baclofen, tizanidine) improves spasticity and gait and helps to correct posture. Oxybutynin is useful in improving urinary urgency, while aminopyridines (4-AP, fampridine, dalfampridine) improve downbeat nystagmus, and acetazolamide and/or 4-AP improve episodic ataxia type 2.23–26

Lastly, patients may also benefit from home adaptations, as well as other social resources made available either by regional governments or at the national level under the Spanish Law for Dependent People. We should be aware of the slowly progressive course of these conditions, as a result of which these patients’ level of disability and quality of life change over time.

Discussion and conclusionsThe lack of a definite diagnosis and thorough assessment of the associated disability in patients with HA and HSP results in considerable uncertainty for patients and their families and hinders access to medical and social resources from which these patients would benefit greatly.

The purpose of these practical recommendations is to improve diagnosis and to assist and standardise the assessment of disability in patients with HA and HSP. Assessment should be universally available, regardless of the healthcare professionals involved (neurologists with or without a specialisation in these conditions, primary care physicians, physiatrists, medical experts, etc) or the autonomous community where the patient is assessed.

Several guidelines have been published for the assessment of disability in patients with rare diseases3,4 or other, more common diseases, including stroke and Parkinson’s disease; however, no specific guidelines have been issued on disability in HA and HSP. We hope that these recommendations, together with the full-text version available at the website of the Spanish Society of Neurology, will assist general neurologists and such other specialists as physiatrists, internists, primary care physicians, and occupational medicine physicians in their clinical practice.

In conclusion, HA and HSP are rare neurodegenerative diseases that frequently present a slowly progressive course, leading to progressive functional disability. Standardised, systematic evaluation of all cases of suspected HA or HSP may improve diagnosis and disability assessment. These practical recommendations are intended to assist general neurologists and other specialists in the diagnosis and management of these patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.