The Frontal Assessment Battery is a short bedside test used to assess executive functions (EF). The aims of the present study were, first, to evaluate the psychometric proprieties of the Spanish version of the FAB (FAB-E) in a representative sample, and second, to establish cut-off points for impairment in executive function according to age and education level.

MethodsA sample of 798 healthy Spanish adult subjects aged 19 to 91 participated in this study. Neuropsychological assessment of participants was conducted using the FAB-E, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Trail Making Test (TMT). We examined internal consistency, intraclass correlation, test-retest reliability, and concurrent and divergent validity. In addition, we established a cut-off point for detecting executive function impairment based on the 5th percentile by age group and education level.

ResultsThe analysis of the psychometric properties of the FAB-E showed good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.60), intraclass correlation (0.72), test-retest reliability (0.70) and concurrent and divergent validity between the TMT (r = −0.523), MMSE (r = 0.426) and the FAB-E. The cut-off points for each age group were 16 points for the ≤ 29 group, 15 points for the 30-39 group, 14 points for the 40-49 and 50-59 groups, 12 points for the 60-69 group, and 10 points for the ≥ 70 age group.

ConclusionsThe psychometric analysis showed that the FAB-E has good validity and reliability. Thus, FAB-E may be a helpful tool to evaluate EF in a healthy Spanish population. In addition, this study provides information on reference data that will be very valuable for clinicians and researchers.

El Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) es una prueba de evaluación breve que se utiliza para evaluar las funciones ejecutivas (FE). Los objetivos del presente estudio fueron, en primer lugar, evaluar las propiedades psicométricas de la versión española del FAB (FAB-E) en una muestra representativa y, en segundo lugar, establecer puntos de corte del deterioro de la función ejecutiva según la edad y el nivel educativo.

MétodosEn este estudio participó una muestra de 798 adultos sanos españoles de 19 a 91 años. La evaluación neuropsicológica de los participantes se realizó mediante el FAB-E, el Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) y el Trail Making Test (TMT). Examinamos la consistencia interna, la correlación intraclase, la confiabilidad test-retest y la validez concurrente y divergente. Además, establecimos un punto de corte para la detección del deterioro de la función ejecutiva en base al percentil 5 por grupo de edad y nivel educativo.

ResultadosEl análisis de las propiedades psicométricas del FAB-E mostró buena consistencia interna (α de Cronbach = 0.60), correlación intraclase (0.72), fiabilidad test-retest (0.70) y validez concurrente y divergente entre TMT (r = -0.523). MMSE (r = 0.426) y FAB-E. Los puntos de corte para cada grupo de edad fueron 16 puntos para el grupo ≤ 29, 15 puntos para el grupo 30-39, 14 puntos para los grupos 40-49 y 50-59, 12 puntos para el grupo 60-69 y 10 puntos para el grupo de edad ≥ 70.

ConclusionesEl análisis psicométrico mostró que el FAB-E tiene buena validez y confiabilidad. Por tanto, FAB-E puede ser una herramienta útil para evaluar la FE en una población española sana. Además, este estudio aporta información sobre datos de referencia que serán de gran valor para clínicos e investigadores.

Executive functions (EF) refer to a complex set of cognitive processes, behavioural, affective and motivational abilities necessary to pursue and achieve a goal, and adaptative functioning in daily life1,2,3. The processes and components involved in EF are related to control and adaptation of thinking and behaviour, working memory, inhibitory control, decision-making, planning and flexibility in behaviour, and effective execution of goal-oriented actions.4–6

Dubois et al.7 developed the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB), a short bedside test used to assess the presence and severity of dysexecutive syndrome affecting cognitive and motor behaviour. This test can be administered in approximately 10 minutes and consists of 6 subscales: conceptualisation, mental flexibility, motor programming, sensitivity to resistance to inference, inhibitory control, and environmental autonomy. The FAB has been translated and culturally adapted in several countries (China, Japan, Turkey, Korea, Croatia, Iran, Portugal, Spain)8–15 and applied in different clinical populations16 such as neurological disorders, chronic diseases, and mental health disturbances.17–25 In addition, analysis of psychometric properties and normative data of the FAB in the healthy population are available for the Italian,3 Taiwanese,26 Brazilian,27 German,28 and Slovakian29 versions. According to these studies, the FAB is a valid and reliable instrument to assess EF in healthy populations.3,26–28.Notably, the availability of normative data on the FAB, stratified by age and education level, provides researchers and clinicians with a helpful tool for screening EF impairment to take preventive actions or complement interventions in different populations.11,30

The Spanish version of the FAB (FAB-E) has recently been published,15 and its psychometric properties of reliability and validity have been examined in a Spanish Parkinson’s disease population.31 However, no study has explored FAB-E performance in the healthy Spanish population. Thus, the present study aimed to examine the validity and reliability of the FAB-E and establish normative data according to age and educational level in a Spanish representative sample of healthy adults.

MethodsStudy design and participantsThis study is part of the NOR+ Project, which aims to establish normative data for relevant assessment instruments used by Spanish healthcare professionals and examine their psychometric properties. This project includes validating the Spanish version of FAB and developing normative data from a representative sample of the Spanish population. To recruit the participants, we used non-probability convenience sampling. Furthermore, to preserve the heterogeneity of the general population, we selected the participants (ie, age, gender, and education level) according to data published by the National Statistics Institute (INE; Instituto Nacional de Estadística).32 The recruitment was carried out from January 2017 to April 2019, and participants were recruited at the street level. After excluding participants without complete information on the main study variables, 798 healthy subjects (435 women and 363 men) aged 19 to 91 were included. Inclusion criteria were being a native Spanish speaker and having a score of 28 or higher in the MiniMental State Examination (MMSE).33 In addition, subjects were excluded if they had a history of the following medical conditions: visual or hearing impairment, psychiatric disease (depression, schizophrenia, substance or alcohol abuse in the last 2 years), a systemic disease associated with cognitive impairment, significant neurological alteration (stroke, acquired brain damage, dementia, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and other movement disorders), primary medical diseases (eg, cancer, heart disease, diabetes, chronic pain), or with comprehension difficulties that limit the performance of the tests.

All participants provided written informed consent, and the Miguel Hernández University ethics committee approved the research protocol (DCP.PPG.02.17).

Instruments and data collectionSpanish version of the Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB-E)The FAB is a screening test for detecting EF impairment. It consists of 6 subtests assessing functions of the frontal lobes: 1) similarities (abstract reasoning/conceptualisation), 2) lexical fluency (mental flexibility),3) motor series (programming and motor planning), 4) conflicting instructions (sensitivity to interference), 5) go-no-go test (inhibitory control and impulsiveness), and 6) prehension behaviour (ability to inhibit a response to sensory stimulation). Each subtest scores between 0 and 3 points. The maximum possible score is 18 points, and higher scores indicate better performance.

Other neuropsychological instrumentsBased on previous validation studies of the FAB, we used an adapted and validated version for the Spanish population of the Trail Making Test B (TMT-B)34 to assess the FAB-E’s concurrent validity. This test evaluates cognitive flexibility and set-shifting abilities by drawing a line linking sequenced letters and numbers. The score is the time in seconds that it takes to complete the task, so subjects have to complete tasks as quickly as possible without a time limit for completing the task. In addition, we used the Spanish version of MMSE33 to check the FAB-E’s divergent validity. The MMSE is an 11-item test measuring general cognitive functioning through five cognitive areas: temporal and spatial orientation, memory, registration, attention and calculation, recall, and constructive language). The maximum score on this test is 30.

In this study, several trained research assistants administered the neuropsychological tests to all participants in one-on-one sessions. On the same occasion, they also collected information on the socio-demographic features of each participant (age, gender, education level, working situation, marital status, and native language). Unfortunately, 19 participants did not complete the TMT-B due to a lack of time at the interview.

Statistical analysisWe analysed data using the R software, version 4.1.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.r-project.org). We applied bilateral statistical tests and established significance at 0.05. Moreover, we used the Lilliefors correction of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to check the normal distribution of the continuous variables. Finally, we described continuous variables as the median and interquartile range (IQR) and categorical variables as frequencies and percentages.

To check the internal consistency of FAB-E, we applied Cronbachs alpha test. As suggested, we accepted a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.70 as a reasonable estimate for internal consistency.35 We also examined the intra-rater and test-retest reliability of the test using intraclass correlation (ICC) and Spearman correlation (rs) coefficients. Reliability measures were analysed in a subsample of 205 participants who were reassessed in a two/four-week interval time after the initial assessment. We considered a value of ≥ 0.75 for a good ICC36 and a coefficient ≥ 0.50 for a strong Spearman correlation.37 Regarding validity measures, we estimated the FAB-E’s concurrent and divergent validity using Spearman correlation coefficients.

Descriptive stratified analyses by age group (≤ 29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69, ≥ 70) and education level (primary studies or less, secondary, university) were carried out to establish the FAB-E normative data. In the ≤ 29 age group, we presented data separating two education levels (secondary studies or less, university) because there were only three people with a primary education level or less. We calculated four cut-off points for each age and education group based on the 5th, 25th, 75th, and 95th percentiles. Finally, we established a cut-off score for detecting EF impairment based on the 5th percentile as proposed by Benke et al.28 and Abrahámová et al. (2020).29

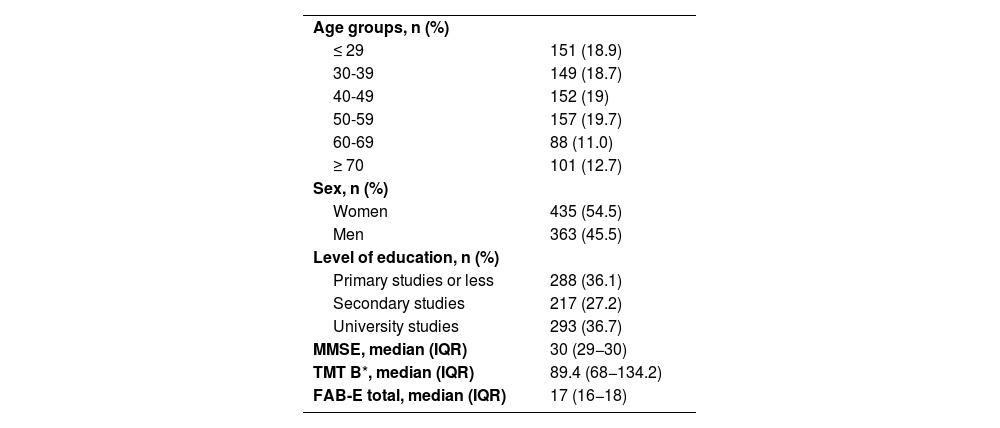

ResultsThe general characteristics of the 798 study participants are displayed in Table 1. The median age of participants was 46 years (IQR: 32-58), 54.5% were women, and around one-third had university studies. More than 40% of participants obtained the best possible total FAB-E score (ceiling effect = 18 points). The proportion of participants scoring at the ceiling decreased from 56.3% (≤ 29 years), to 54.4% (30-39), to 53.3% (40-49), to 38.9% (50-59), to 22.7% (60-69), and to 12.9% (≥ 70 years). Only one person aged 76 obtained the worst possible score (floor effect = 7 points).

General characteristics of participants in the Nor+ Project (n = 798).

| Age groups, n (%) | |

| ≤ 29 | 151 (18.9) |

| 30-39 | 149 (18.7) |

| 40-49 | 152 (19) |

| 50-59 | 157 (19.7) |

| 60-69 | 88 (11.0) |

| ≥ 70 | 101 (12.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Women | 435 (54.5) |

| Men | 363 (45.5) |

| Level of education, n (%) | |

| Primary studies or less | 288 (36.1) |

| Secondary studies | 217 (27.2) |

| University studies | 293 (36.7) |

| MMSE, median (IQR) | 30 (29−30) |

| TMT B*, median (IQR) | 89.4 (68−134.2) |

| FAB-E total, median (IQR) | 17 (16−18) |

FAB-E: Spanish version of the Frontal Assessment Battery; IQR: interquartile range; MMSE: Mini–Mental State Evaluation; n: number of participants; TMT B: Trail Making Test part B.

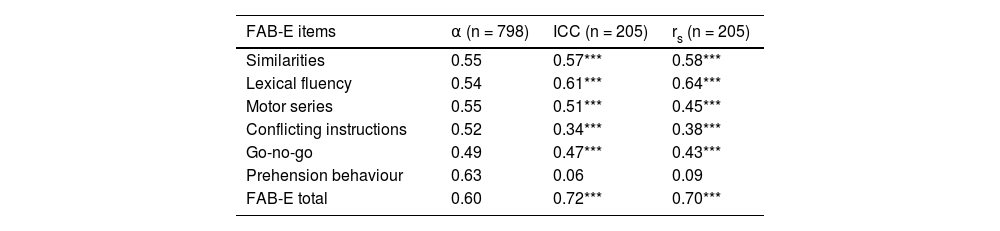

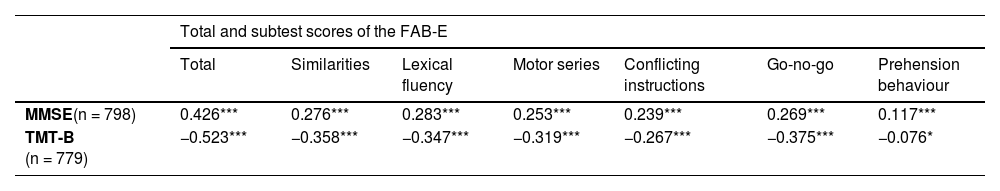

Table 2 displays the FAB-E’s internal consistency and reliability measures in a representative sample of Spanish adults. The results suggested a moderate internal consistency of the FAB-E (Cronbach's α = 0.60), ranging from 0.49 (when excluding the Go-no-go item) to 0.63 (when excluding the prehension behavioural item). Good inter-rater (ICC = 0.72) and test-retest reliabilities (rs = 0.70) were observed in FAB-E. Regarding the validity measures displayed in Table 3, total FAB-E scores showed a moderate-strong correlation with total MMSE (rs = 0.426, ie, divergent validity) and a strong correlation with TMT-B (rs = −0.523, i.e., concurrent validity). The subtest scores of the FAB-E generally showed moderate correlations with both MMSE and TMT-B, although they were slightly higher with TMT-B. The prehension behaviour item showed low concurrent and divergent validities.

Internal consistency and reliability measures of the FAB-E scores.

| FAB-E items | α (n = 798) | ICC (n = 205) | rs (n = 205) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Similarities | 0.55 | 0.57*** | 0.58*** |

| Lexical fluency | 0.54 | 0.61*** | 0.64*** |

| Motor series | 0.55 | 0.51*** | 0.45*** |

| Conflicting instructions | 0.52 | 0.34*** | 0.38*** |

| Go-no-go | 0.49 | 0.47*** | 0.43*** |

| Prehension behaviour | 0.63 | 0.06 | 0.09 |

| FAB-E total | 0.60 | 0.72*** | 0.70*** |

α: Cronbach's alpha; ICC: Intraclass correlation coefficient; n: number of participants; rs: Spearman correlation coefficient.

*P < .05.

**P < .01.

Divergent and concurrent validity using Spearman correlations between the total and subtest scores of the FAB-E and the MMSE and TMT-B.

| Total and subtest scores of the FAB-E | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Similarities | Lexical fluency | Motor series | Conflicting instructions | Go-no-go | Prehension behaviour | |

| MMSE(n = 798) | 0.426*** | 0.276*** | 0.283*** | 0.253*** | 0.239*** | 0.269*** | 0.117*** |

| TMT-B (n = 779) | −0.523*** | −0.358*** | −0.347*** | −0.319*** | −0.267*** | −0.375*** | −0.076* |

MMSE: Mini Mental State Examination; TMT: Trail Making Test.

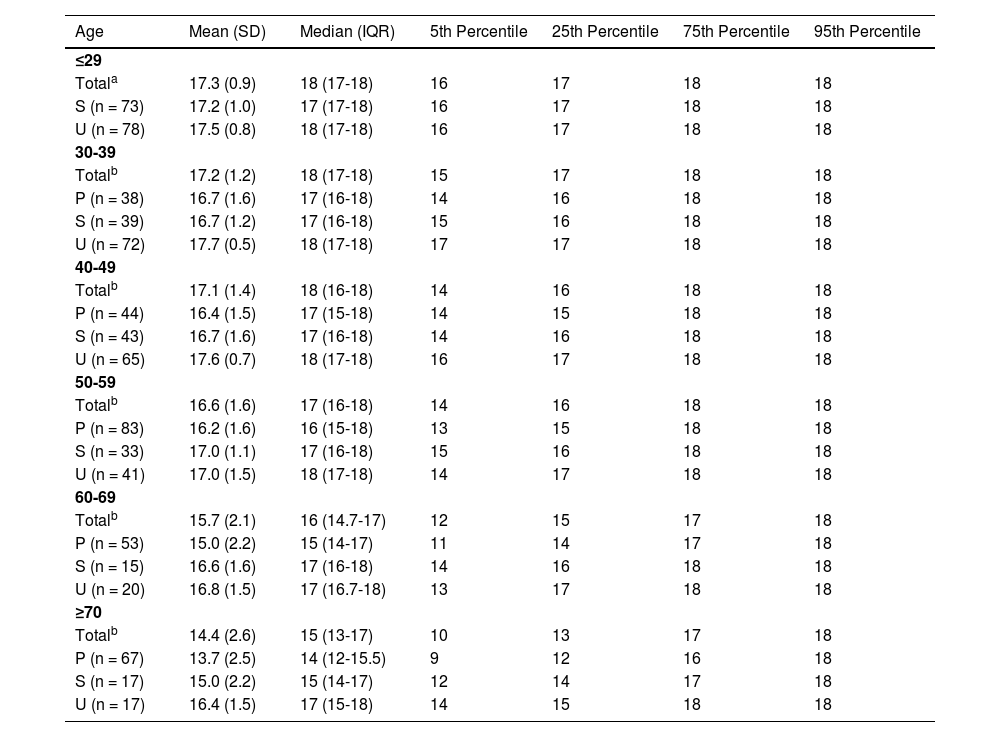

**p < 0.01.

Table 4 shows the normative data of the FAB-E in a Spanish adult sample population stratified by age and education level. Overall, we observed differences in the total scores of FAB-E across age and education levels. Those participants with lower education levels and older age had the lowest total FAB-E scores. Regardless of education level and age, total FAB-E scores remained similar in those that scored at the 75th and 95th percentiles. However, we observed a considerable decrease in total FAB-E performance in those who scored at the 25th percentile, especially in those with primary studies within the 60-69 and ≥ 70 age groups. The cut-off scores for detecting EF impairment based on the 5th percentile were 16 (≤ 29 group), 15 (30-39 group), 14 (40-49 and 50-59 groups), 12 (60-69 group), and 10 (≥ 70 age group).

Normative data of the FAB-E in a healthy adult Spanish population (n = 798).

| Age | Mean (SD) | Median (IQR) | 5th Percentile | 25th Percentile | 75th Percentile | 95th Percentile |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤29 | ||||||

| Totala | 17.3 (0.9) | 18 (17-18) | 16 | 17 | 18 | 18 |

| S (n = 73) | 17.2 (1.0) | 17 (17-18) | 16 | 17 | 18 | 18 |

| U (n = 78) | 17.5 (0.8) | 18 (17-18) | 16 | 17 | 18 | 18 |

| 30-39 | ||||||

| Totalb | 17.2 (1.2) | 18 (17-18) | 15 | 17 | 18 | 18 |

| P (n = 38) | 16.7 (1.6) | 17 (16-18) | 14 | 16 | 18 | 18 |

| S (n = 39) | 16.7 (1.2) | 17 (16-18) | 15 | 16 | 18 | 18 |

| U (n = 72) | 17.7 (0.5) | 18 (17-18) | 17 | 17 | 18 | 18 |

| 40-49 | ||||||

| Totalb | 17.1 (1.4) | 18 (16-18) | 14 | 16 | 18 | 18 |

| P (n = 44) | 16.4 (1.5) | 17 (15-18) | 14 | 15 | 18 | 18 |

| S (n = 43) | 16.7 (1.6) | 17 (16-18) | 14 | 16 | 18 | 18 |

| U (n = 65) | 17.6 (0.7) | 18 (17-18) | 16 | 17 | 18 | 18 |

| 50-59 | ||||||

| Totalb | 16.6 (1.6) | 17 (16-18) | 14 | 16 | 18 | 18 |

| P (n = 83) | 16.2 (1.6) | 16 (15-18) | 13 | 15 | 18 | 18 |

| S (n = 33) | 17.0 (1.1) | 17 (16-18) | 15 | 16 | 18 | 18 |

| U (n = 41) | 17.0 (1.5) | 18 (17-18) | 14 | 17 | 18 | 18 |

| 60-69 | ||||||

| Totalb | 15.7 (2.1) | 16 (14.7-17) | 12 | 15 | 17 | 18 |

| P (n = 53) | 15.0 (2.2) | 15 (14-17) | 11 | 14 | 17 | 18 |

| S (n = 15) | 16.6 (1.6) | 17 (16-18) | 14 | 16 | 18 | 18 |

| U (n = 20) | 16.8 (1.5) | 17 (16.7-18) | 13 | 17 | 18 | 18 |

| ≥70 | ||||||

| Totalb | 14.4 (2.6) | 15 (13-17) | 10 | 13 | 17 | 18 |

| P (n = 67) | 13.7 (2.5) | 14 (12-15.5) | 9 | 12 | 16 | 18 |

| S (n = 17) | 15.0 (2.2) | 15 (14-17) | 12 | 14 | 17 | 18 |

| U (n = 17) | 16.4 (1.5) | 17 (15-18) | 14 | 15 | 18 | 18 |

IQR: interquartile ranges; n: number of participants; P: primary education or less; S: secondary education; SD: Standard deviation; U: university education.

This study showed that the FAB-E has an acceptable internal consistency, good inter-rater and test-retest reliability, and moderate concurrent and divergent validity to assess EF in the healthy adult Spanish population. In addition, we determined normative data by age and education level to establish the cut-off points of the FAB-E for detecting EF impairment. To our knowledge, this is the first time a study explores the FAB’s psychometric properties in a representative general Spanish population and provides normative reference values of EF for specific conditions such as age and education level.

Compared with previous studies, the internal consistency of the FAB-E was higher than that estimated for the German version of the FAB28 (Cronbach’s α = 0.46), very similar to that for the Taiwanese version26 (Cronbach’s α = 0.68), and lower than that for the Korean version11 (Cronbach’s α = 0.80). One possible explanation for the modest internal consistency of the FAB-E could be attributed to the participants’ age in our study. For example, the mean age of the participants in the study by Kim et al.11 was 74, while those who participated in our study were 46, which could indicate that FAB might perform better in older people. Moreover, following the interpretation given by Benke et al.,28 the FAB includes different cognitive domains grouped under the broad term of EF, which could explain the low intercorrelation or internal consistency of FAB’s items. In line with previous research on normative data for the FAB,11,26,28we observed that the prehension behaviour item showed the lowest coefficient correlations and that, when it was deleted, the FAB-E’s internal consistency improved (Cronbach’s α = 0.63). In this respect, prior research and Ilardi et al.38 have pointed out that this item has a poor discriminant power because it yields a marked ceiling effect in healthy and clinical populations, thereby weakening the FAB’s validity. In response to this shortcoming, a new shortened 15-item version of the FAB has recently been proposed.38 However, reliability measures showed the FAB-E has a good reproducibility with results similar to the previous studies.3,11,26 In addition, total FAB-E scores displayed a good concurrent validity with TMT B (r = −0.523), which is equivalent to the estimate of the Italian version of the FAB tested in healthy participants.17 Consistent with former studies, the results for divergent validity showed that the total FAB-E scores correlated with the MMSE.3,10,27,29,30,39

Since sociodemographic features influence the FAB’s performance, we provided normative data of FAB-E stratified by education and age groups, as in previous studies conducted in different countries.3,11,27–30 Moreover, we established cut-off points to detect impairment of EF in a healthy population based on the 5th percentile, as proposed in prior studies by Benke et al.28 and Abrahámová et al.29 We observed slight variations between the cut-off points estimated in our study and in the latter, probably due to differences in the age of the population studied. While our study involved subjects between 19 and 91 years old with a median (IQR) age of 46 (32-58), the participants in the study by Benke et al.28 were aged 50 years or older and those in the study of Abrahámová et al.29 had a mean age of 55.3 years. Nevertheless, the total scores of FAB-E were lower as the age increased and the education level decreased, which is in line with the prior research.3,11,13,18,26

This study has some limitations and strengths that we should acknowledge. Compared to previous studies in healthy populations, our study had the largest sample size (n = 798), followed by the studies of the FAB’s Korean version11 (n = 635) and Slovak version29 (n = 487). Although the sample size of our groups stratified by age and education level was variable, our study is representative of the Spanish population. We estimated the sampling according to age, sex, and education level based on the reference population rates published by the National Statistics Institute of Spain.32 Regarding the neuropsychological instruments, the TMT-B39 is not totally equivalent to the FAB, although both tools assess global EF, so we analysed concurrent validity using TMT as the gold standard. Moreover, a score of 28 in the MMSE may not be representative of the cognitive status of people aged 70 or older, especially those with a lower education level. It is known that in older people with low educational backgrounds, scores of 27 or lower in the MMSE may not indicate a pathological condition.40 In our study, among subjects aged 70 or older with primary education (n = 67), 20.6% were only able to read or write. In addition, it should be noted that normative data of any assessment instrument are only valid for the study population where they were estimated. Therefore, they are unsuitable for other countries or subjects with different sociodemographic characteristics. Nevertheless, normative data and cut-off points for the FAB-E may contribute to the improvement of its diagnostic capacity as a screening instrument for EF impairment.

ConclusionsThis study shows the FAB-E has good psychometric properties, indicating that it can be used as a reliable and valid tool to evaluate EF in a healthy adult Spanish population. Furthermore, this study provides normative data and cut-off points for the FAB-E for healthy subjects according to age group and education level. Notably, the information on reference data will help compare patients’ EF performance with a normative sample, which will be extremely valuable in parallel for medical care and further research in the area.

Funding informationThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors would like to thank all the anonymous participants included in the sample, the Pathology and Surgery Department of UMH, and the students who collaborated in the recruitment process.