Stroke has a significant impact on mental health and health-related quality of life (HRQoL); these aspects have not been sufficiently studied in young stroke.

ObjectivesTo evaluate HRQoL, mental health, and the relationship between these variables and the incorporation of young adults into working life after stroke.

Material and methods: We conducted a prospective descriptive study of patients with JS between 2016 and 2017, using such questionnaires and scales as EuroQol-5D, the 36-item Short Form Health Survey, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS), modified Rankin Scale (mRS), 12-item General Health Questionnaire, Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Rating Scales, and BURQOL-meter; tests were administered at 2 interviews, held 6 and 12 months after stroke.

ResultsWe analysed 41 patients, with a mean age of 41.8 years. At one year, the mean NIHSS score was 0.54 and mRS score was 0–2 in 95.1%. No differences were observed over time in quality of life or mental health scales. Prevalence rates for depression and anxiety at one year were 46.3% and 41.5%, respectively. Male sex and active employment were associated with better HRQoL. A total of 41.5% of patients were in work at one year after the stroke. Statistically significant associations were observed between quality of life, mental health, and incorporation into working life.

ConclusionsYoung stroke affects HRQoL, and patients are at high risk of anxiety and depression, underdiagnosed and undertreated disorders that affect quality of life and the return to work, which decreases after stroke in young adults.

El ictus provoca un importante impacto sobre la salud mental y la calidad de vida relacionada con la salud (CVRS); aspectos no suficientemente estudiados para el ictus juvenil (IJ).

ObjetivosEvaluar la CVRS, la salud mental y la relación entre éstas y la incorporación a la actividad laboral tras un IJ.

Material y métodosEstudio descriptivo prospectivo de pacientes con IJ entre 2016−2017. Se emplearon los cuestionarios y escalas EuroQol-5D, SF-36, NIHSS, Rankin-m, GHQ12, Hamilton Ansiedad, Hamilton Depresión y BURQOL-meter, realizados en dos entrevistas, a los 6 y 12 meses tras el IJ.

ResultadosFueron analizados 41 pacientes, 41.8 años de media. Tras un año la media de NIHSS fue 0.54 y el Rankin 0–2, 95.1%. No hubo diferencias en las escalas de calidad de vida y salud mental en el tiempo. La tasa de depresión y ansiedad al año fue de 46.3% y 41.5% respectivamente. Los hombres y trabajadores tienen mejor CVRS. El 41.5% de los pacientes trabajaban tras un año del IJ. La calidad de vida, salud mental y la incorporación a la vida laboral tienen relación estadísticamente significativa entre sí.

ConclusionesEl IJ altera la CVRS y los pacientes tienen alto riesgo sufrir ansiedad y depresión, patologías infradiagnosticadas e infratratadas, las cuales condicionan la calidad de vida, así como la incorporación a la vida laboral, que se ve mermada tras el IJ.

Young stroke (YS) is defined as cerebrovascular disease in patients younger than 55 years.1,2

The incidence of YS has increased in recent years, probably as a result of the increase in the use of toxic substances, the prevalence of vascular risk factors, environmental pollution, and lifestyle changes.3,4 The incidence of YS in Europe is approximately 8 cases/100 000 population, with a slightly lower rate among women.5

Stroke is a frequent cause of disability; in the specific case of YS, the greater survival rate is associated with an increased risk of neuropsychiatric comorbidities. The aim of this study is to examine health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among patients with YS, as well as the incidence of anxiety and depression in this population and their relationship with these patients’ employment status.

Material and methodsWe conducted a prospective, descriptive study of patients aged 18–50 years who were admitted to a tertiary-level hospital for acute stroke treatment between 2016 and 2017. We excluded patients who: 1) presented language disorders preventing their participation in any stage of the study and who did not have a proxy (a friend or relative who could respond on the patient’s behalf); 2) were resident in a foreign country; 3) could not be located; and 4) did not agree to participate in the study. Patients with language disorders that improved in the assessment at 12 months did participate in the study.

The study was conducted in 3 stages: collection of data related to the care provided for stroke; and 2 in-person or telephone interviews, at 6 and 12 months after stroke.

During these interviews, we administered different questionnaires assessing HRQOL (EuroQoL-5D and the 36-item Short-Form Health Survey [SF-36]) and mental health (Hamilton Depression and Anxiety Rating Scales [HAM-D and HAM-A, respectively] and the 12-item General Health Questionnaire [GHQ-12]), and an adapted version of the Social Economic Burden and Health-Related Quality of Life in patients with Rare Diseases in Europe instrument (BURQOL-RD), which collected information on patients’ employment status. We also recorded National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) and modified Rankin Scale (mRS) scores.6 Where necessary, scores were recoded according to the user manuals for each instrument.6–11 For HAM-A and HAM-D scores, cut-off points were used to establish the presence and severity of anxiety and depression6,8,12,13: HAM-A: 0–7 points: no or minimal anxiety; 8–14 points: mild anxiety; 15–23 points: moderate anxiety; ≥ 24 points: severe anxiety14; HAM-D: 0–6 points: no depression; 7–17 points: mild depression; 18–24 points: moderate depression; 25–52 points: severe depression.6,8,13

Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS® statistics software. We performed a descriptive analysis of frequencies, analysed dependencies with the chi-square test, compared scale scores using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test and comparison of means, studied correlations using the Spearman rho statistic, and compared factors using the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test. The reliability of the scales was analysed with the Cronbach alpha statistic, with a lower bound of 70%. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P < .05 (95% confidence interval).

ResultsA total of 107 patients with YS were admitted to the hospital, accounting for 11.7% of all strokes (n = 894). Twenty-six percent were excluded, and 34.4% did not agree to participate, despite an improvement in participation with increased use of telephone interviews. We interviewed a total of 41 patients: 40 at 6 months and 41 at 12 months (the difference is due to improvement in a language disorder in one patient). Surveys were completed by patients in 97.5% of cases; in one case, a proxy completed the survey due to severe aphasia in the patient.

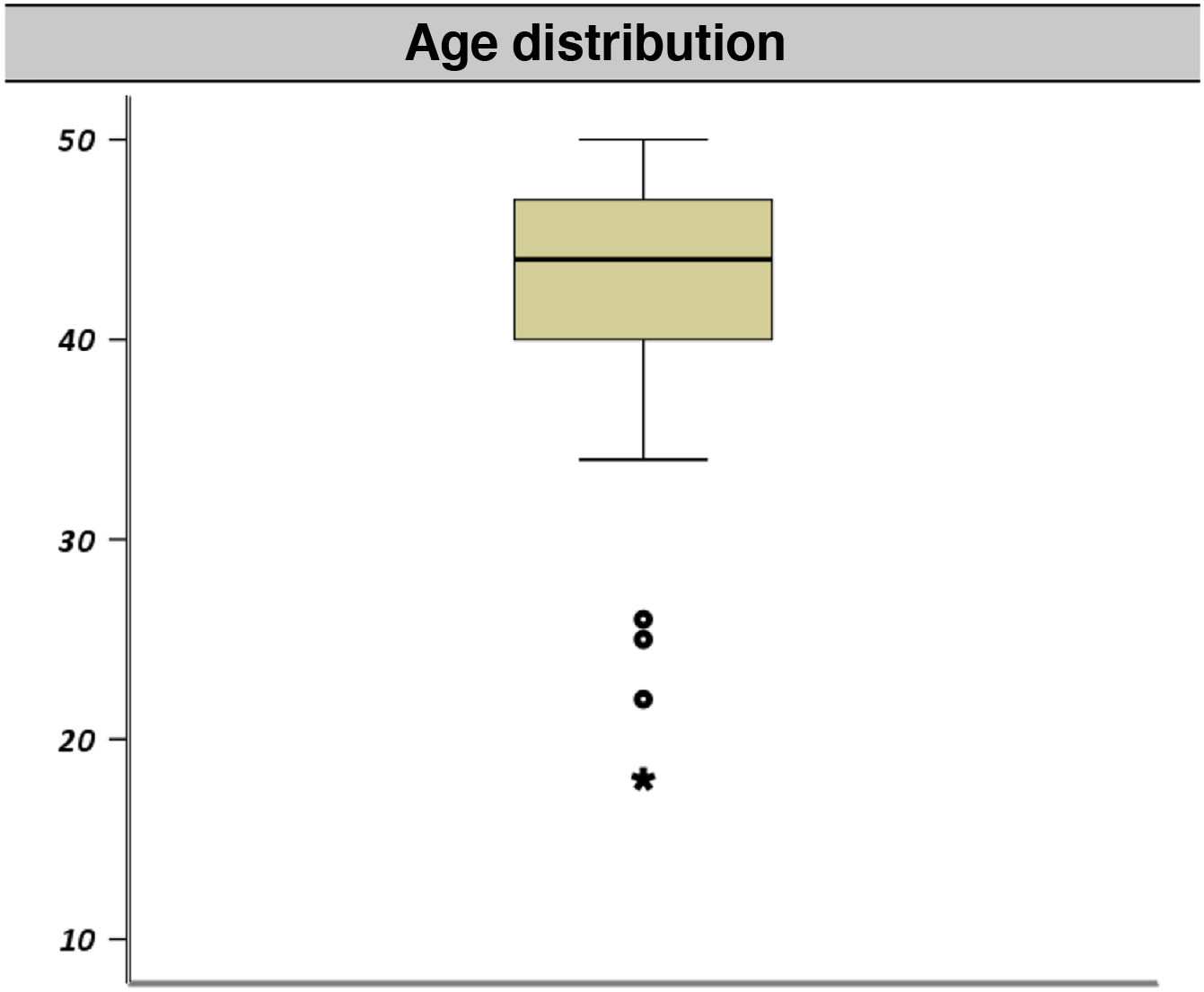

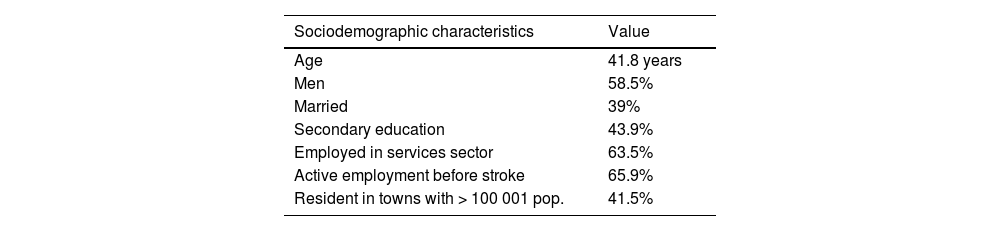

Mean age (standard deviation [SD]) was 41.8 (7.41) years; most patients were men (58.5%). The main sociodemographic characteristics are presented in Table 1; Fig. 1 shows participants’ age distribution.

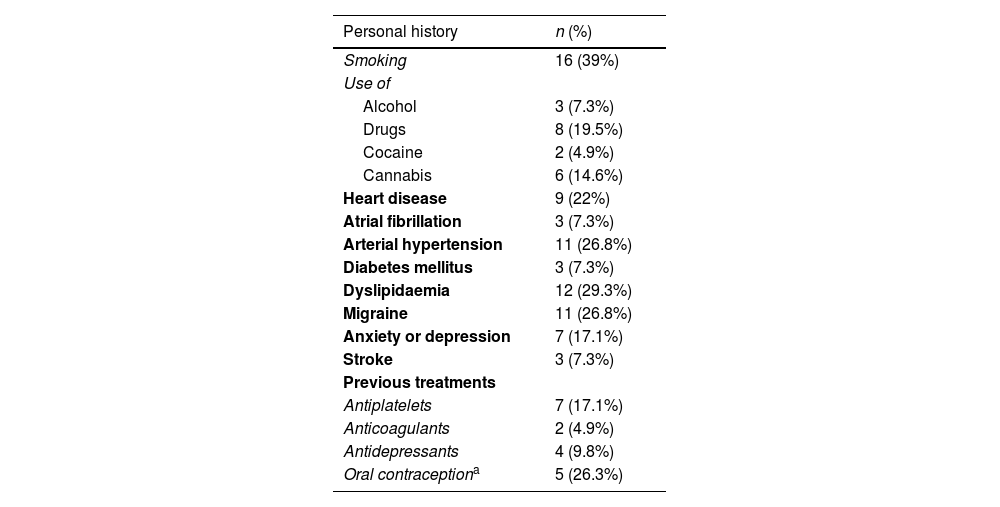

Regarding patients’ personal history (Table 2), the most frequent vascular risk factors were smoking (39%), dyslipidaemia (29.3%), and arterial hypertension (26.8%). Some 19.5% reported use of some illegal drug.

Personal history.

| Personal history | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Smoking | 16 (39%) |

| Use of | |

| Alcohol | 3 (7.3%) |

| Drugs | 8 (19.5%) |

| Cocaine | 2 (4.9%) |

| Cannabis | 6 (14.6%) |

| Heart disease | 9 (22%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 3 (7.3%) |

| Arterial hypertension | 11 (26.8%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (7.3%) |

| Dyslipidaemia | 12 (29.3%) |

| Migraine | 11 (26.8%) |

| Anxiety or depression | 7 (17.1%) |

| Stroke | 3 (7.3%) |

| Previous treatments | |

| Antiplatelets | 7 (17.1%) |

| Anticoagulants | 2 (4.9%) |

| Antidepressants | 4 (9.8%) |

| Oral contraceptiona | 5 (26.3%) |

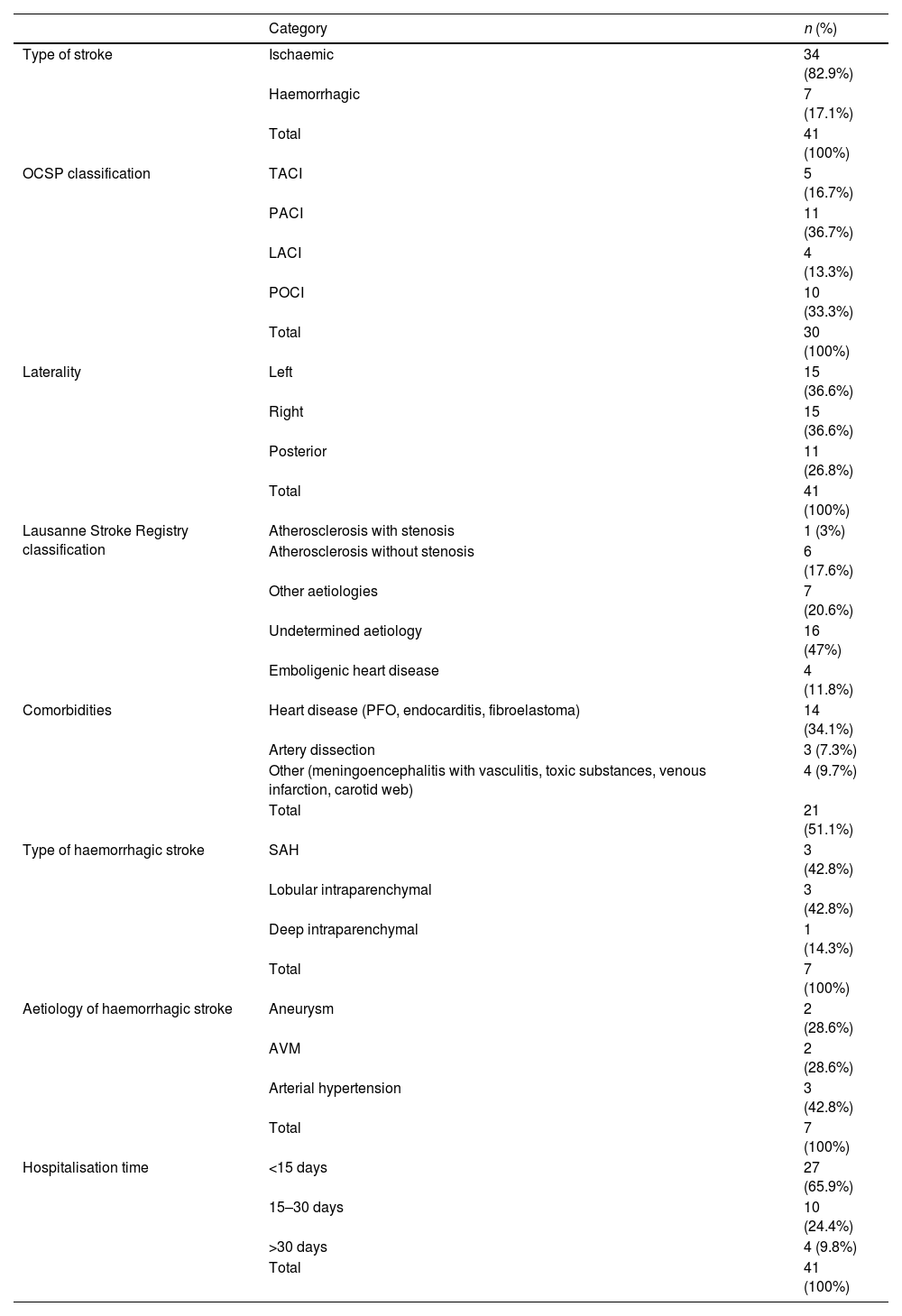

Stroke was ischaemic in 82% of cases, with 9.7% being transient ischaemic attacks; the most frequent type of stroke was partial anterior circulation infarct (36.7%), with stroke of undetermined cause being the most frequent aetiology (47%). Among haemorrhagic strokes, subarachnoid haemorrhage and lobular intraparenchymal haemorrhage were the most frequent types (42.8% each; Table 3).

Overview of stroke characteristics.

| Category | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of stroke | Ischaemic | 34 (82.9%) |

| Haemorrhagic | 7 (17.1%) | |

| Total | 41 (100%) | |

| OCSP classification | TACI | 5 (16.7%) |

| PACI | 11 (36.7%) | |

| LACI | 4 (13.3%) | |

| POCI | 10 (33.3%) | |

| Total | 30 (100%) | |

| Laterality | Left | 15 (36.6%) |

| Right | 15 (36.6%) | |

| Posterior | 11 (26.8%) | |

| Total | 41 (100%) | |

| Lausanne Stroke Registry classification | Atherosclerosis with stenosis | 1 (3%) |

| Atherosclerosis without stenosis | 6 (17.6%) | |

| Other aetiologies | 7 (20.6%) | |

| Undetermined aetiology | 16 (47%) | |

| Emboligenic heart disease | 4 (11.8%) | |

| Comorbidities | Heart disease (PFO, endocarditis, fibroelastoma) | 14 (34.1%) |

| Artery dissection | 3 (7.3%) | |

| Other (meningoencephalitis with vasculitis, toxic substances, venous infarction, carotid web) | 4 (9.7%) | |

| Total | 21 (51.1%) | |

| Type of haemorrhagic stroke | SAH | 3 (42.8%) |

| Lobular intraparenchymal | 3 (42.8%) | |

| Deep intraparenchymal | 1 (14.3%) | |

| Total | 7 (100%) | |

| Aetiology of haemorrhagic stroke | Aneurysm | 2 (28.6%) |

| AVM | 2 (28.6%) | |

| Arterial hypertension | 3 (42.8%) | |

| Total | 7 (100%) | |

| Hospitalisation time | <15 days | 27 (65.9%) |

| 15–30 days | 10 (24.4%) | |

| >30 days | 4 (9.8%) | |

| Total | 41 (100%) |

AVM: arteriovenous malformation; LACI: lacunar infarction; OCSP: Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project; PACI: partial anterior circulation infarction; PFO: patent foramen ovale; POCI: posterior circulation infarction; SAH: subarachnoid haemorrhage; TACI: total anterior circulation infarction.

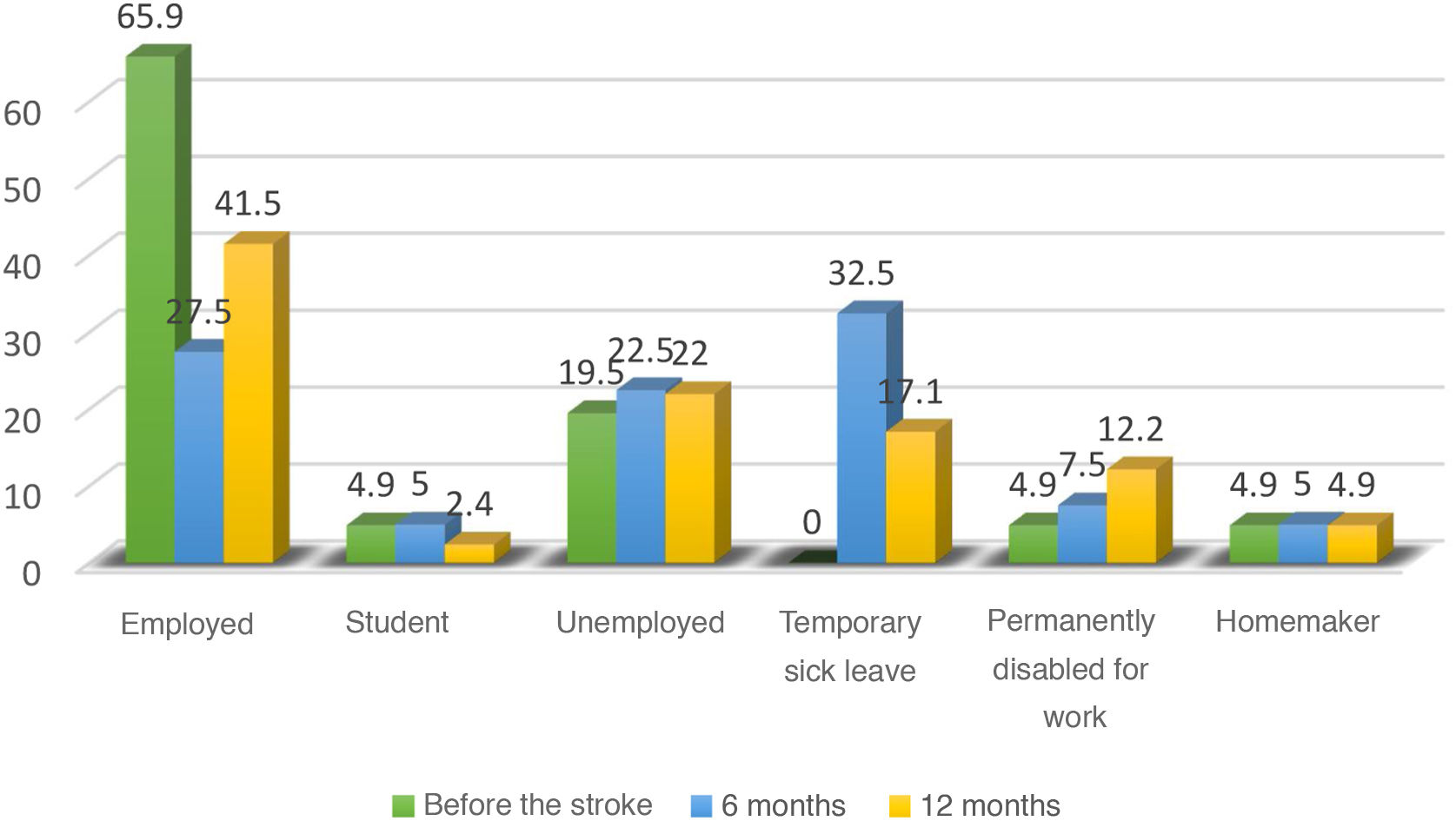

Prior to stroke, 65.9% of patients were in active employment; after stroke, this percentage decreased to 27.5% at 6 months and 41.5% at 12 months (Fig. 2). At one year after stroke, an increase was observed in the percentage of patients on temporary or permanent sick leave (17.1% and 12.2%, respectively).

Among patients who were in employment prior to YS, the mean (SD) duration of sick leave at one year was 191.85 (143.608) days.

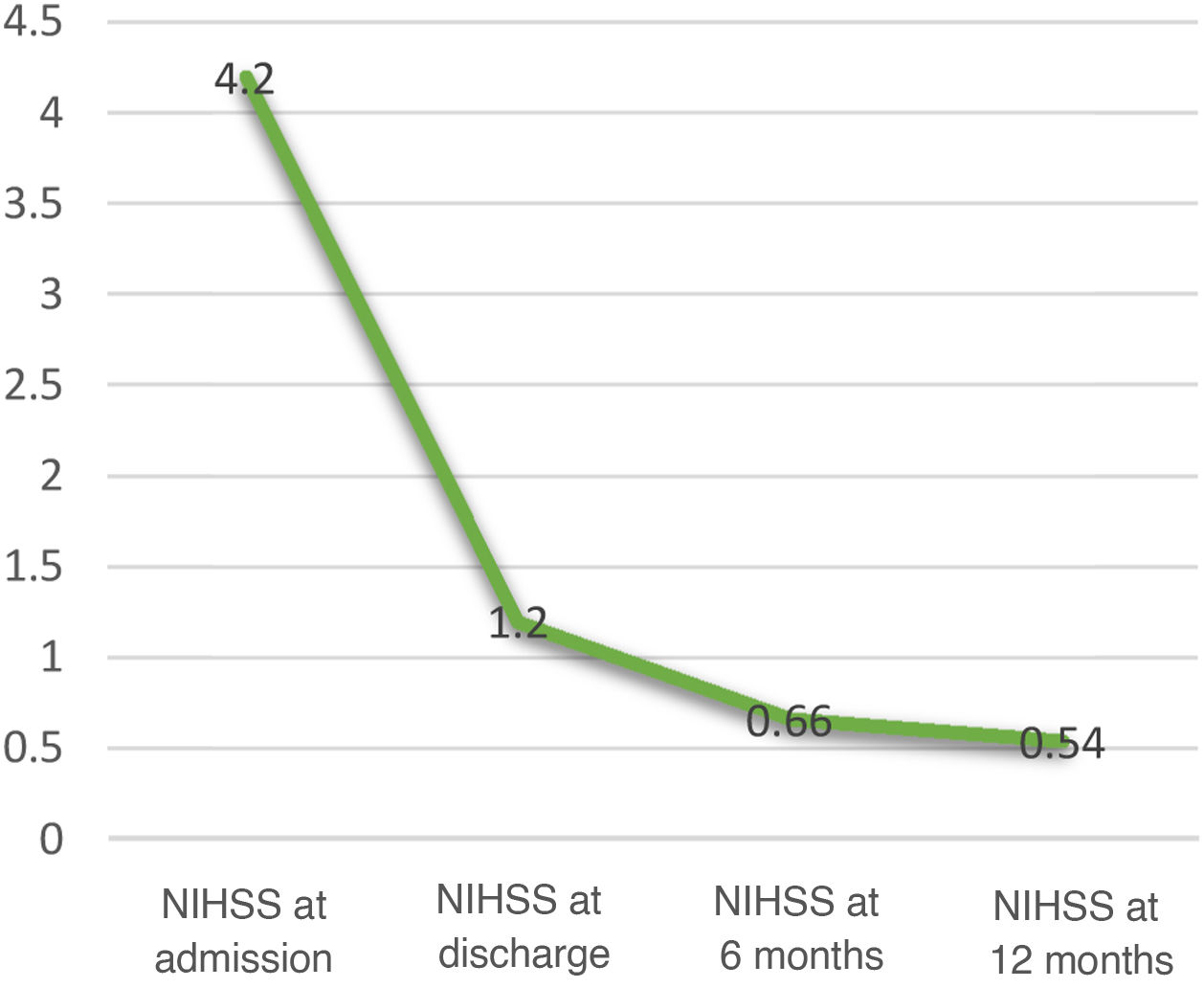

Disability and functional statusNIHSSMean NIHSS score decreased over time, from 4.2 at admission to 0.54 at one year (P < .001) (Fig. 3).

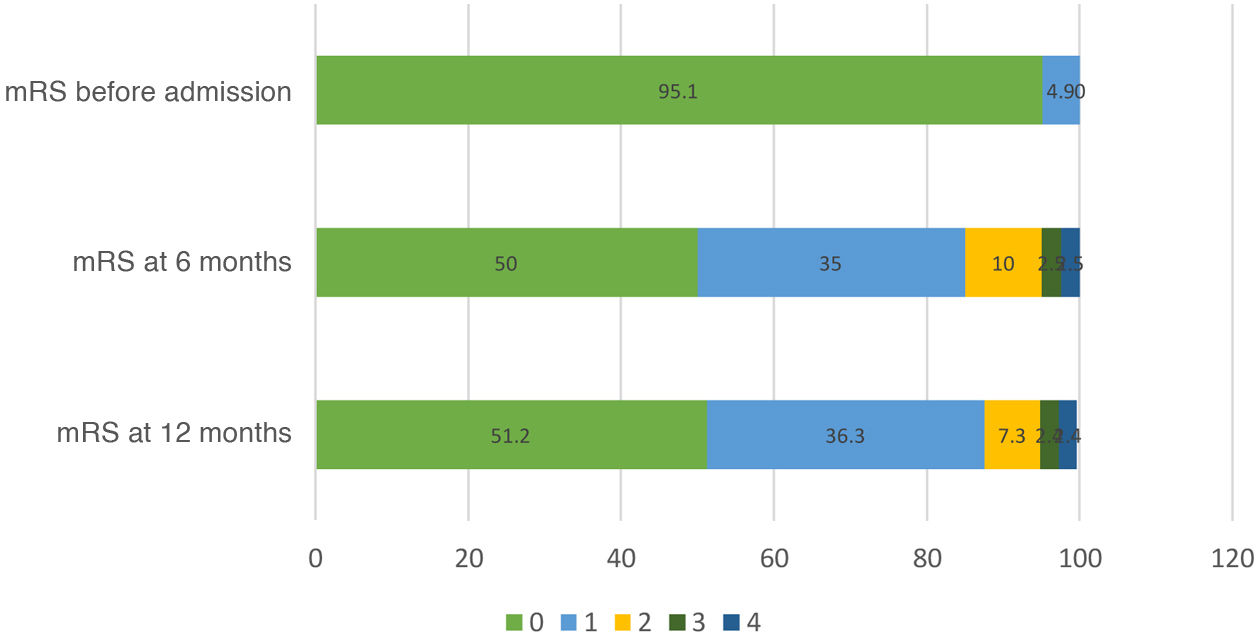

Modified Rankin ScaleFollowing stroke, mRS scores of 0 were recorded in 50% and in 51.2% of patients at 6 and 12 months, respectively. The great majority of patients were functionally independent (mRS scores of 0–2) at 6 and 12 months (95% and 95.1%, respectively) (Fig. 4).

Quality of life scalesIn these scales, higher scores indicate better quality of life.

EuroQol-5DMean (SD) EuroQoL-5D scores at 6 and 12 months were 0.67 (0.231) and 0.666 (0.237), respectively; this difference was not significant (P = .872). Mean score on the visual analogue scale was 62.48 (23.108) at 6 months and 62.39 (26.561) at 12 months.

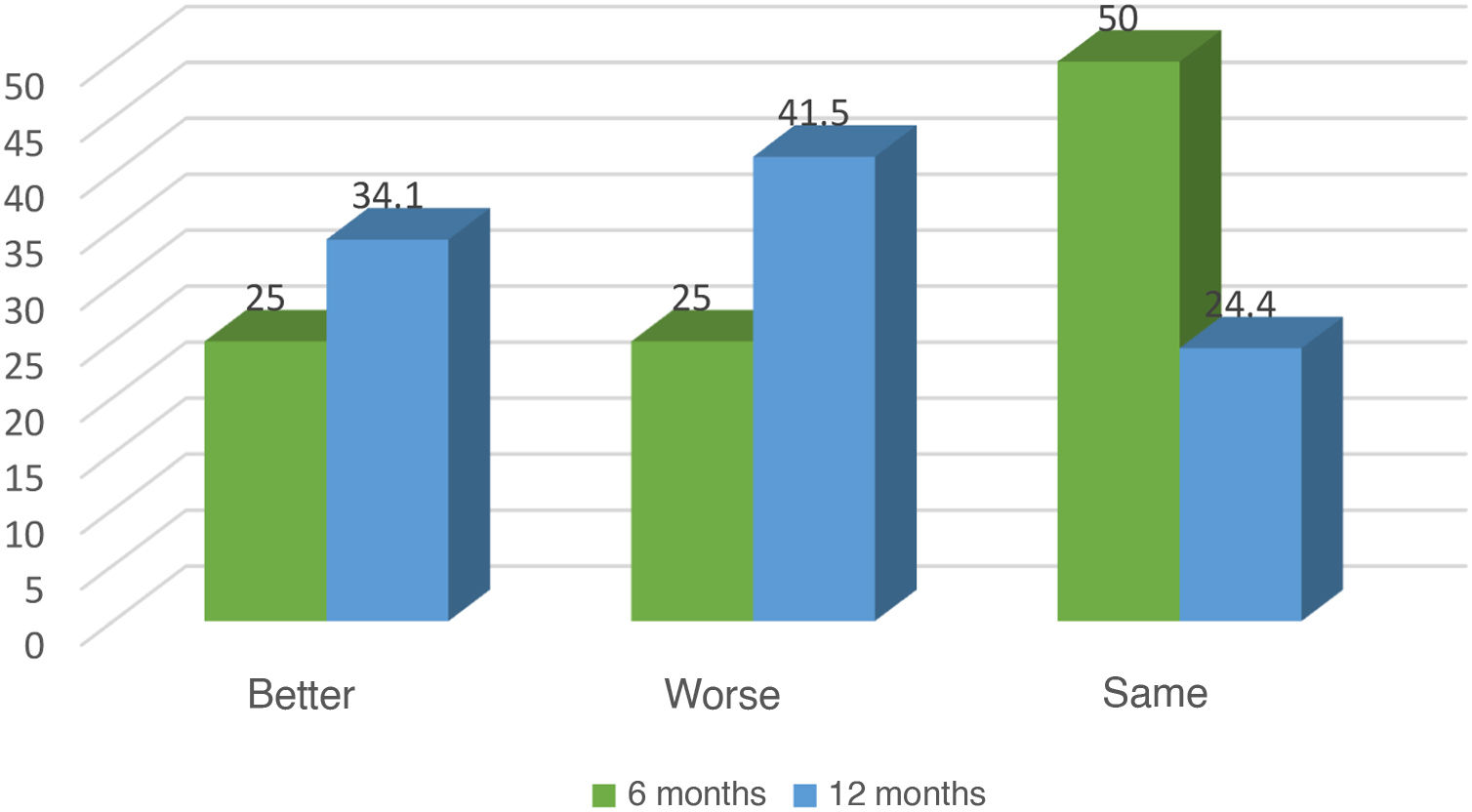

The dimensions with the lowest scores were pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. No difference was observed over time for this scale. Perceived health status compared with the last 12 months, at the time of the interviews, showed no statistically significant association with time. As shown in Fig. 5, 50% of patients reported poorer health status at 6 months, compared to 24.4% of patients at 12 months (P = .073).

The EuroQol-5D presented a Cronbach alpha value of 0.743.

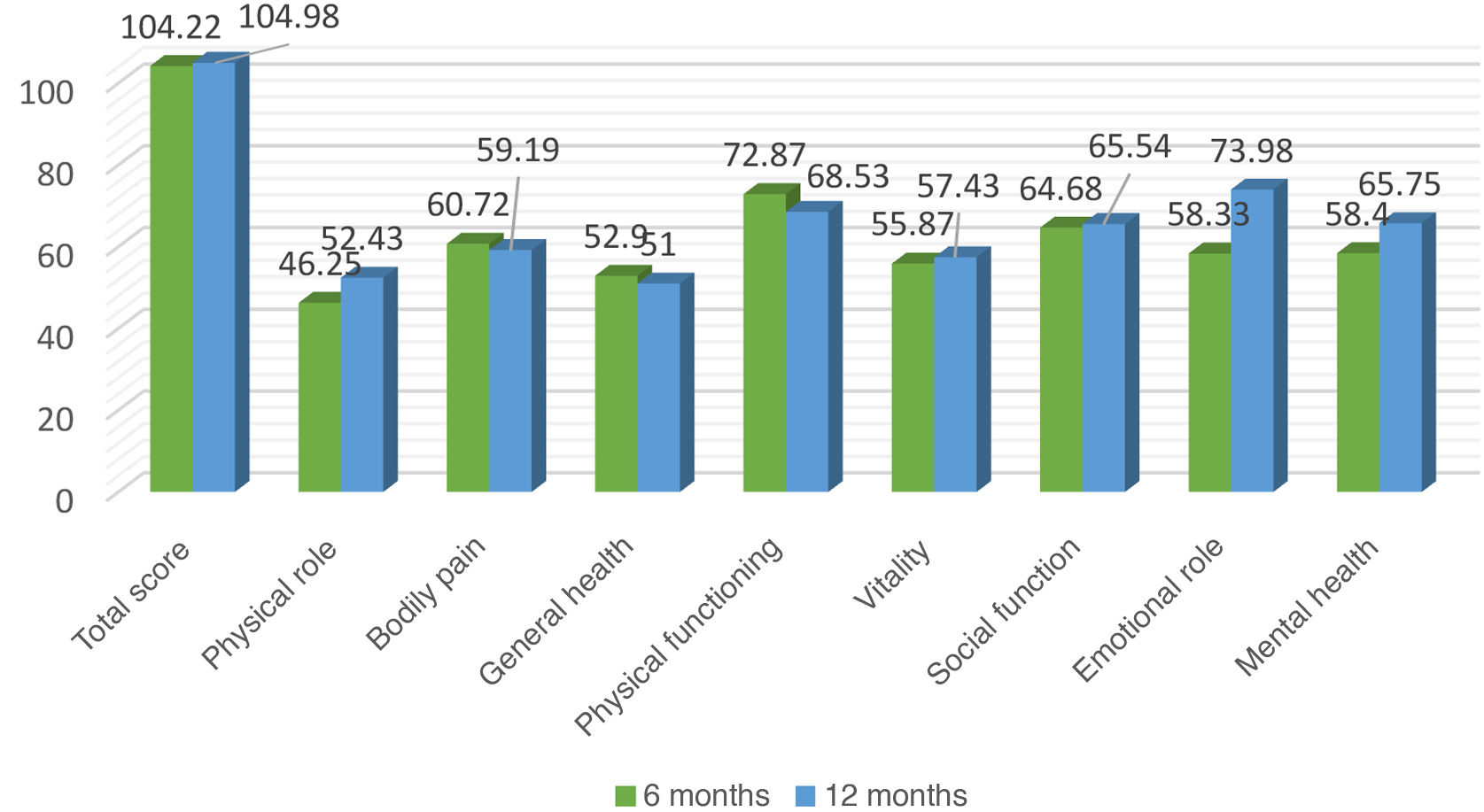

SF-36 questionnaireThe mean total score (SD) was 104.22 (22.72) at 6 months and 104.98 (21.91) at 12 months; therefore, quality of life did not change over time.

The dimension showing the poorest scores was physical role, followed by general health and vitality (Fig. 6). Some dimensions showed worsening at one year, such as general health, bodily pain, and physical functioning, although these differences were not statistically significant.

The dimension that improved the most at one year after YS was emotional role, with significant differences between scores at 6 and 12 months (P = .009); mental health also showed a significant improvement (P = .004).

The mean physical component scores at 6 and 12 months were 43.51 (9.909) and 41.08 (11.9), respectively; this difference was not significant. However, the mental component did show an improvement (40.32 [12.092] vs 45.87 [12.44]; P = .002).

At 6 months, patients with YS most frequently felt that their health was somewhat worse than a year earlier (32.5%); however, after 12 months, 29.3% considered their health to be somewhat better than a year earlier; this improvement in self-perceived health was statistically significant (P = .004).

The mean score for each role is below that reported for the reference population.12 Only 2 roles (mental health and social role functioning) showed better quality of life in some age groups than in the reference population.

The SF-36 presented a Cronbach alpha value of 0.550. However, the results are consistent with those of other scales.

Mental health scalesHigher scores indicate poorer mental health in all 3 of the scales used.

Hamilton Depression Rating ScaleMean (SD) HAM-D scores at 6 and 12 months were 9.3 (9.016) and 8.71 (7.16), respectively; this difference was not significant (P = .599).

According to results from this scale, 50% of patients at 6 months and 53.7% at 12 months did not have depression. However, 35% and 34.1%, respectively, presented mild depression. The percentage of patients with severe depression decreased from 13% at 6 months to 7% at 12 months.

The HAM-D presented a Cronbach alpha value of 0.844.

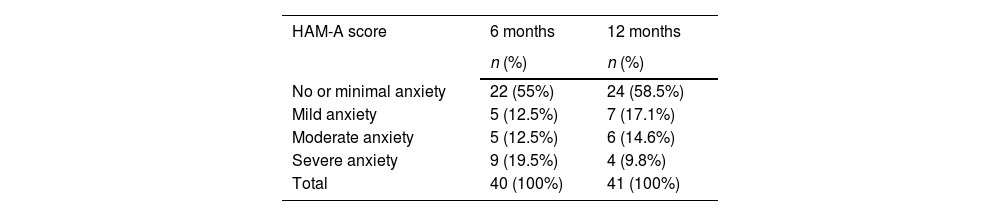

Hamilton Anxiety Rating ScaleMean total HAM-A score was 11 (12.064) at 6 months and 9.61 (9.932) at 12 months, with scores of 6.23 (6.1) and 5.8 (4.981), respectively, for somatic anxiety and 4.78 (6.31) and 3.8 (5.492), respectively, for psychic anxiety. No change was detected over time for the total score (P = .369) or for either subscale (P = .774 and P = .108).

Approximately 50% to 60% of patients did not present anxiety (Table 4). At 6 months, 19.5% of patients had severe anxiety.

The most frequent symptoms were intellectual symptoms, observed in 62.5% of patients at 6 months and in 75.6% at 12 months. The most severe symptoms were intellectual symptoms and depressed mood.

The HAM-A presented a Cronbach alpha value of 0.923.

General Health QuestionnaireThe mean GHQ-12 score was 4.53 (4.309) at 6 months and 3.29 (3.823) at 12 months; this difference was not significant (P = .058).

Scores on this scale indicated some psychiatric disorder on the anxiety/depression spectrum in 50% of patients at 6 months and 46.3% at 12 months. The item with the worst scores was the sensation of being unable to overcome difficulties, which 34.1% of patients reported feeling “rather more than usual.”

GHQ-12 scores were consistent with HAM-A and HAM-D scores, showing that nearly half of the sample presented anxiety or depression.

The GHQ-12 presented a Cronbach alpha value of 0.922.

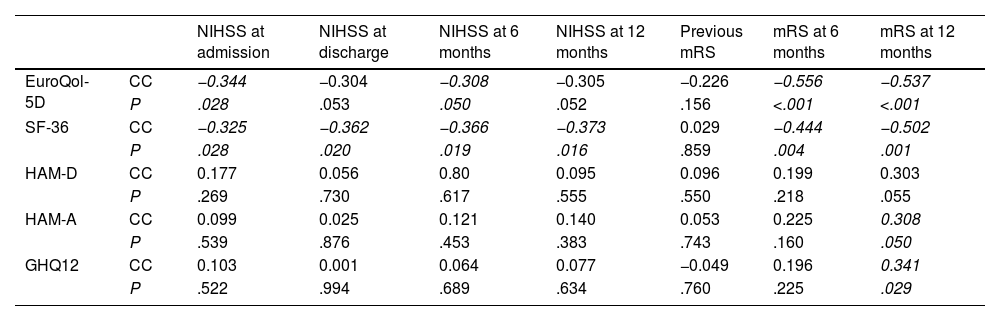

Comparison between scalesThe analysis of correlation between quality of life and mental health scales identified statistically significant associations in all cases. Quality of life scale scores (EuroQol-5D and SF-36) were positively correlated, with higher scores in one scale being associated with higher scores on the other. The same was true for mental health scales.

Quality of life scores were negatively correlated with mental health scores, with better quality of life (higher scores) being associated with better mental health (lower scores).

Analysis of the relationship with neurological function and disability (Table 5) revealed an inverse correlation between the EuroQol-5D and SF-36 scales, on the one hand, and the NIHSS and mRS, on the other. This suggests that poorer physical status is associated with poorer quality of life. Prior mRS score in these patients did not influence quality of life after YS.

Correlations between quality of life, mental health, functional status, and disability scales.

| NIHSS at admission | NIHSS at discharge | NIHSS at 6 months | NIHSS at 12 months | Previous mRS | mRS at 6 months | mRS at 12 months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EuroQol-5D | CC | −0.344 | −0.304 | −0.308 | −0.305 | −0.226 | −0.556 | −0.537 |

| P | .028 | .053 | .050 | .052 | .156 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| SF-36 | CC | −0.325 | −0.362 | −0.366 | −0.373 | 0.029 | −0.444 | −0.502 |

| P | .028 | .020 | .019 | .016 | .859 | .004 | .001 | |

| HAM-D | CC | 0.177 | 0.056 | 0.80 | 0.095 | 0.096 | 0.199 | 0.303 |

| P | .269 | .730 | .617 | .555 | .550 | .218 | .055 | |

| HAM-A | CC | 0.099 | 0.025 | 0.121 | 0.140 | 0.053 | 0.225 | 0.308 |

| P | .539 | .876 | .453 | .383 | .743 | .160 | .050 | |

| GHQ12 | CC | 0.103 | 0.001 | 0.064 | 0.077 | −0.049 | 0.196 | 0.341 |

| P | .522 | .994 | .689 | .634 | .760 | .225 | .029 |

CC: correlation coefficient; GHQ-12: 12-item General Health Questionnaire; HAM-A: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAM-D: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; mRS: modified Rankin Scale; NIHSS: National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; SF-36: 36-item Short-Form Health Survey.

Statistically significant associations are shown in italics (P < .05).

HAM-D score was not correlated with NIHSS or mRS scores (P = .55). However, as occurred with the GHQ-12, we did observe a positive correlation between HAM-A and mRS at one year, indicating that greater disability is associated with poorer mental health.

EuroQol-5D scores were significantly associated with patient age, revealing better quality of life among younger patients.

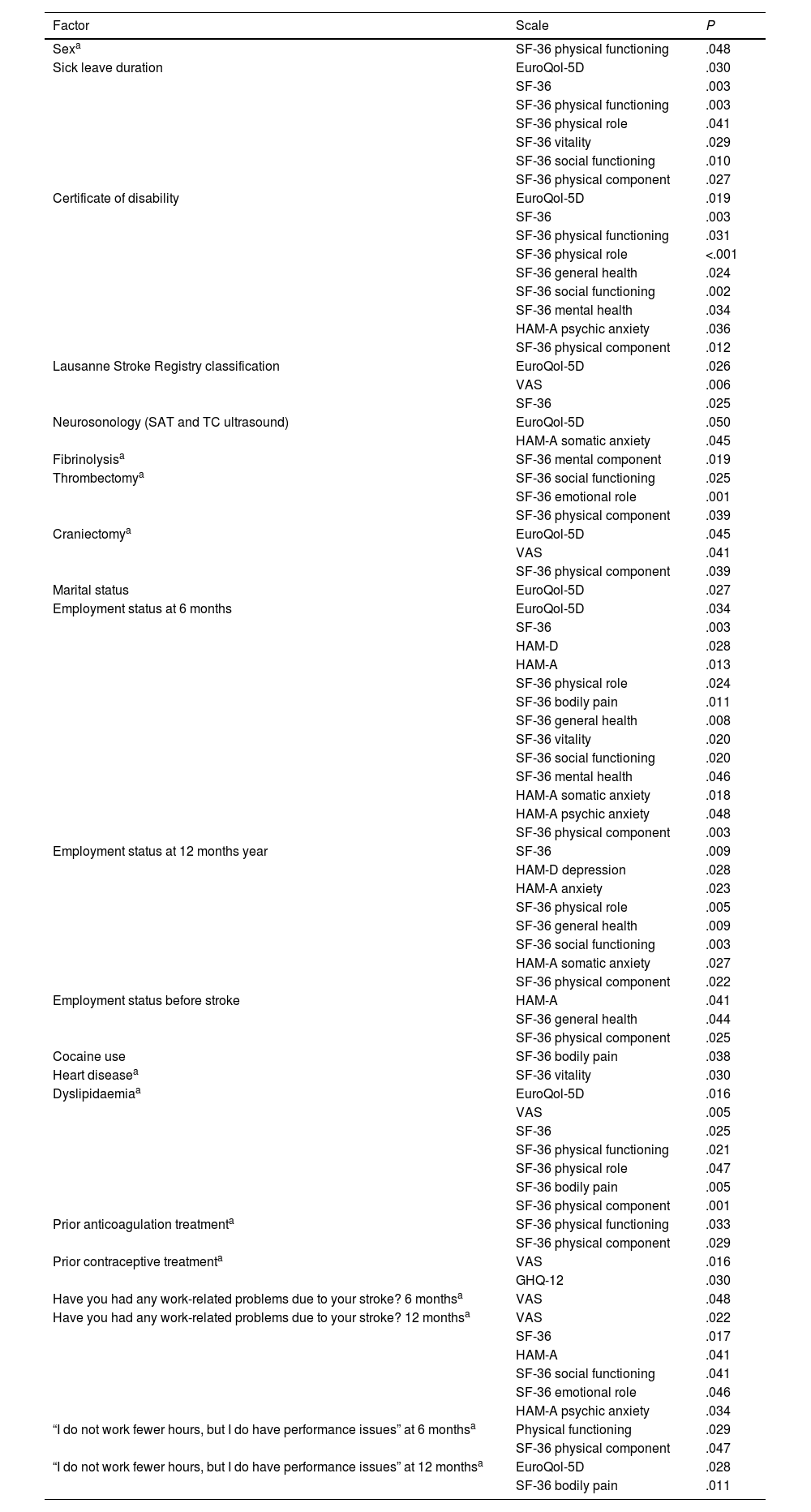

Comparison between factorsTable 6 presents statistically significant associations identified in the comparison between the factors studied and quality of life and mental health scales.

Associations between factors and quality of life and mental health scales.

| Factor | Scale | P |

|---|---|---|

| Sexa | SF-36 physical functioning | .048 |

| Sick leave duration | EuroQol-5D | .030 |

| SF-36 | .003 | |

| SF-36 physical functioning | .003 | |

| SF-36 physical role | .041 | |

| SF-36 vitality | .029 | |

| SF-36 social functioning | .010 | |

| SF-36 physical component | .027 | |

| Certificate of disability | EuroQol-5D | .019 |

| SF-36 | .003 | |

| SF-36 physical functioning | .031 | |

| SF-36 physical role | <.001 | |

| SF-36 general health | .024 | |

| SF-36 social functioning | .002 | |

| SF-36 mental health | .034 | |

| HAM-A psychic anxiety | .036 | |

| SF-36 physical component | .012 | |

| Lausanne Stroke Registry classification | EuroQol-5D | .026 |

| VAS | .006 | |

| SF-36 | .025 | |

| Neurosonology (SAT and TC ultrasound) | EuroQol-5D | .050 |

| HAM-A somatic anxiety | .045 | |

| Fibrinolysisa | SF-36 mental component | .019 |

| Thrombectomya | SF-36 social functioning | .025 |

| SF-36 emotional role | .001 | |

| SF-36 physical component | .039 | |

| Craniectomya | EuroQol-5D | .045 |

| VAS | .041 | |

| SF-36 physical component | .039 | |

| Marital status | EuroQol-5D | .027 |

| Employment status at 6 months | EuroQol-5D | .034 |

| SF-36 | .003 | |

| HAM-D | .028 | |

| HAM-A | .013 | |

| SF-36 physical role | .024 | |

| SF-36 bodily pain | .011 | |

| SF-36 general health | .008 | |

| SF-36 vitality | .020 | |

| SF-36 social functioning | .020 | |

| SF-36 mental health | .046 | |

| HAM-A somatic anxiety | .018 | |

| HAM-A psychic anxiety | .048 | |

| SF-36 physical component | .003 | |

| Employment status at 12 months year | SF-36 | .009 |

| HAM-D depression | .028 | |

| HAM-A anxiety | .023 | |

| SF-36 physical role | .005 | |

| SF-36 general health | .009 | |

| SF-36 social functioning | .003 | |

| HAM-A somatic anxiety | .027 | |

| SF-36 physical component | .022 | |

| Employment status before stroke | HAM-A | .041 |

| SF-36 general health | .044 | |

| SF-36 physical component | .025 | |

| Cocaine use | SF-36 bodily pain | .038 |

| Heart diseasea | SF-36 vitality | .030 |

| Dyslipidaemiaa | EuroQol-5D | .016 |

| VAS | .005 | |

| SF-36 | .025 | |

| SF-36 physical functioning | .021 | |

| SF-36 physical role | .047 | |

| SF-36 bodily pain | .005 | |

| SF-36 physical component | .001 | |

| Prior anticoagulation treatmenta | SF-36 physical functioning | .033 |

| SF-36 physical component | .029 | |

| Prior contraceptive treatmenta | VAS | .016 |

| GHQ-12 | .030 | |

| Have you had any work-related problems due to your stroke? 6 monthsa | VAS | .048 |

| Have you had any work-related problems due to your stroke? 12 monthsa | VAS | .022 |

| SF-36 | .017 | |

| HAM-A | .041 | |

| SF-36 social functioning | .041 | |

| SF-36 emotional role | .046 | |

| HAM-A psychic anxiety | .034 | |

| “I do not work fewer hours, but I do have performance issues” at 6 monthsa | Physical functioning | .029 |

| SF-36 physical component | .047 | |

| “I do not work fewer hours, but I do have performance issues” at 12 monthsa | EuroQol-5D | .028 |

| SF-36 bodily pain | .011 |

GHQ-12: 12-item General Health Questionnaire; HAM-A: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HAM-D: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale; SAT: supra-aortic trunks; SF-36: 36-item Short-Form Health Survey; TC: transcranial; VAS: visual analogue scale.

Men presented better quality of life in terms of physical function role. Patients undergoing fibrinolysis/mechanical thrombectomy had poorer quality of life. Similarly, patients undergoing craniectomy scored lower on the EuroQol-5D scale and visual analogue scale. Unexpectedly, patients with history of heart disease prior to YS had greater vitality (SF-36). Absence of dyslipidaemia was associated with higher quality of life scores (SF-36).

Patients taking oral anticoagulants had poorer physical function (SF-36). Patients receiving oral contraceptives scored higher for self-perceived health (visual analogue scale) and lower on the GHQ-12, indicating better mental health.

Patients’ employment status had an impact on quality of life and mental health: patients without work-related problems at 6 months and those who were working and studying presented better quality of life scores than those with permanent disability for work or who had not been on sick leave. Unexpectedly, patients who reported work performance issues scored better for physical function (SF-36) at 6 months and on the EuroQol-5D at 12 months after YS, suggesting that the performance issue was not physical. We also observed better quality of life among patients who had not requested or received a certificate of disability than in those who did have these certificates, with better scores in all scales.

As we might expect, both quality of life and mental health were poorer among patients who were not in active employment or were permanently disabled for work, compared to patients who were in active employment or education. Psychic anxiety was greater among patients with certificates of disability than in those who had not requested or received these certificates; patients who had work-related problems at 12 months after stroke had more anxiety (HAM-A), particularly psychic anxiety.

Regarding the aetiological classification of stroke, patients with stroke of undetermined cause had better quality of life than those with cardioembolic stroke or atherothrombotic stroke without stenosis.

DiscussionYS is a significant health problem, affecting patients’ mental health and quality of life. Analysis of scale scores a year after stroke revealed no difference in quality of life or mental health, although we did observe changes in self-perceived health and an improvement in the mental component of the SF-36. The dimensions of quality of life presenting the poorest scores were anxiety, depression, pain, physical role, and general health.

Quality of life and mental health in these patients were related, and neither aspect should be overlooked. A patient’s physical functioning and disability will influence their quality of life and mental health; therefore, it is crucial that sequelae be as mild as possible, and that they are treated early.

Multiple factors may influence quality of life. Men more frequently present YS (58.5%), and have better quality of life; quality of life is also better among younger patients. Presence of vascular risk factors was not excessive; the most frequent was smoking (39%), and 19.5% reported using some illegal drug. The risk factors for YS also include migraine with aura2; migraine (with or without aura) was more frequent in our sample than in the general population (26.8% vs 15%).15 Quality of life after YS is affected by certain vascular risk factors; specifically, we observed poorer quality of life among patients with dyslipidaemia. Surprisingly, patients with history of heart disease scored best for vitality in quality of life scales.

Oral contraceptives increase the risk of stroke.5 Among female patients, 26.3% were receiving this treatment; these patients had better self-perceived health and better mental health scale scores.

The most frequent type of stroke was ischaemic stroke (82%), with undetermined causes being the most frequent aetiology (47%), with a slightly higher rate than that reported in the literature (39.7%).16 Interestingly, patients with stroke of undetermined aetiology had better quality of life.

Few patients received treatment in the acute phase (17.1%). However, those who did receive this treatment presented poorer quality of life; furthermore, an association between physical function and quality of life was observed in these patients, probably due to their poorer physical function, with higher NIHSS scores. Craniectomy, as we might expect, was also associated with poorer quality of life.

Regarding anxiety and depression, 17.1% of patients had history of these disorders prior to stroke; however, at one year, practically half had anxiety or depression. This is a higher rate than those observed in other studies (30%).17 In this case, relevant findings were the increased incidence compared to the values that might be expected, and the lack of treatment, possibly due to underdiagnosis. At one year after stroke, only 22% of patients were taking antidepressants; only 13% had consulted a psychologist and 2.4% a psychiatrist. Compared to stroke in older patients, YS presents better survival rates and prognosis, but a greater risk of neuropsychiatric disorders.2,18 Therefore, we must be proactive in the detection and treatment of these disorders, taking into account the impact of mental health on these patients’ quality of life. The increased prevalence of anxiety and depression may be related to the low percentage of patients receiving treatment.

The functional status of these patients after discharge is good, with a mean NIHSS score of 0.54 at one year after discharge. This is further supported by the fact that 95% of patients presented mRS scores of 0–2 at one year after YS. The fact that these patients are functionally independent but present poorer quality of life and mental health outcomes indicates that the alterations to their quality of life are not purely due to physical reasons.

The return to work is also altered after YS; this is closely related to quality of life, and is highly significant in the light of the young age of these patients. At 6 months after YS, only 27.5% of patients were working, with this percentage rising to 41.5% at 12 months, a similar rate to that reported by other authors (23%–40%).1,2,19 Those studies established predictive parameters for the return to work, with the majority of factors preventing the return to work being physical. However, as mentioned above, these patients present excellent physical function; therefore, it is essential to analyse the cause of the problem. Employment status has an impact on patients’ quality of life and mental health, as demonstrated by the poorer quality of life among patients who had to stop working. Similarly, patients with prolonged sick leave or work-related problems presented greater levels of anxiety and depression.

Current healthcare approaches aim to evaluate and quantify physical sequelae, with less emphasis placed on the patient’s sense of well-being and relationship with their environment. Currently, the objective form of classifying these patients is based on scales that are not specific to YS, measuring physical sequelae and disability. As demonstrated by our results, enabling the patient to adapt to the return to work and social life is equally as important as minimising physical sequelae after the acute stage of stroke. Quality of life is rarely assessed at routine consultations, despite its impact on the return to work and on mental health.

Our results suggest that quality of life among patients with YS is not only physical, but also psychic and executive. The same level of emphasis should be placed on all dimensions of HRQOL. It should be noted that these patients are of working age, and all the alterations described may prevent them from continuing their professional and personal development.

Our findings suggest a need to modify healthcare approaches to these patients, with special emphasis placed on the assessment and treatment of non-physical sequelae.

ConclusionsPatients with YS present poorer HRQOL and high risk of developing anxiety and depression. The situation does not improve over the course of a year, with few changes in quality of life or mental health, possibly due to the underdiagnosis and undertreatment of these disorders. Quality of life parameters in these patients are poorer than in the general population. Patients with YS present more problems than those reflected by disability scale scores, and their reincorporation into working life is essential to their quality of life and mental health.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from any public, commercial, or non-profit organisation.