A 65-year-old man consulted for dyspnea grade 1 on the mMRC scale (Medical Research Council scale) and wheezing for six months. Physical examination and laboratory tests were unremarkable. Spirometry revealed normal flow-volume loops, with a forced vital capacity (FVC) of 78% of predicted, a forced vital capacity in 1 second (FEV1) of 73% of predicted, an FEV1/FVC of 79% of predicted and a post-bronchodilator FEV1 of 85%. Bronchial asthma was diagnosed; and budesonide/formoterol fumarate dihydrate 160/4.5μg, one inhalation every 12h, was prescribed. Symptoms persisted despite increasing the drug dose to two puffs every 12h. During the eight months following diagnosis, he required hospital admission on two occasions. In both cases, for pneumonia. The last episode had an unfavorable clinical course. Chest CT showed reticulonodular lesions (Fig. 1A and B). At the same time, the patient began to present petechial lesions and gingival bleeding; laboratory tests showed plateletopenia (14,300/μL), the other parameters being within normal limits.

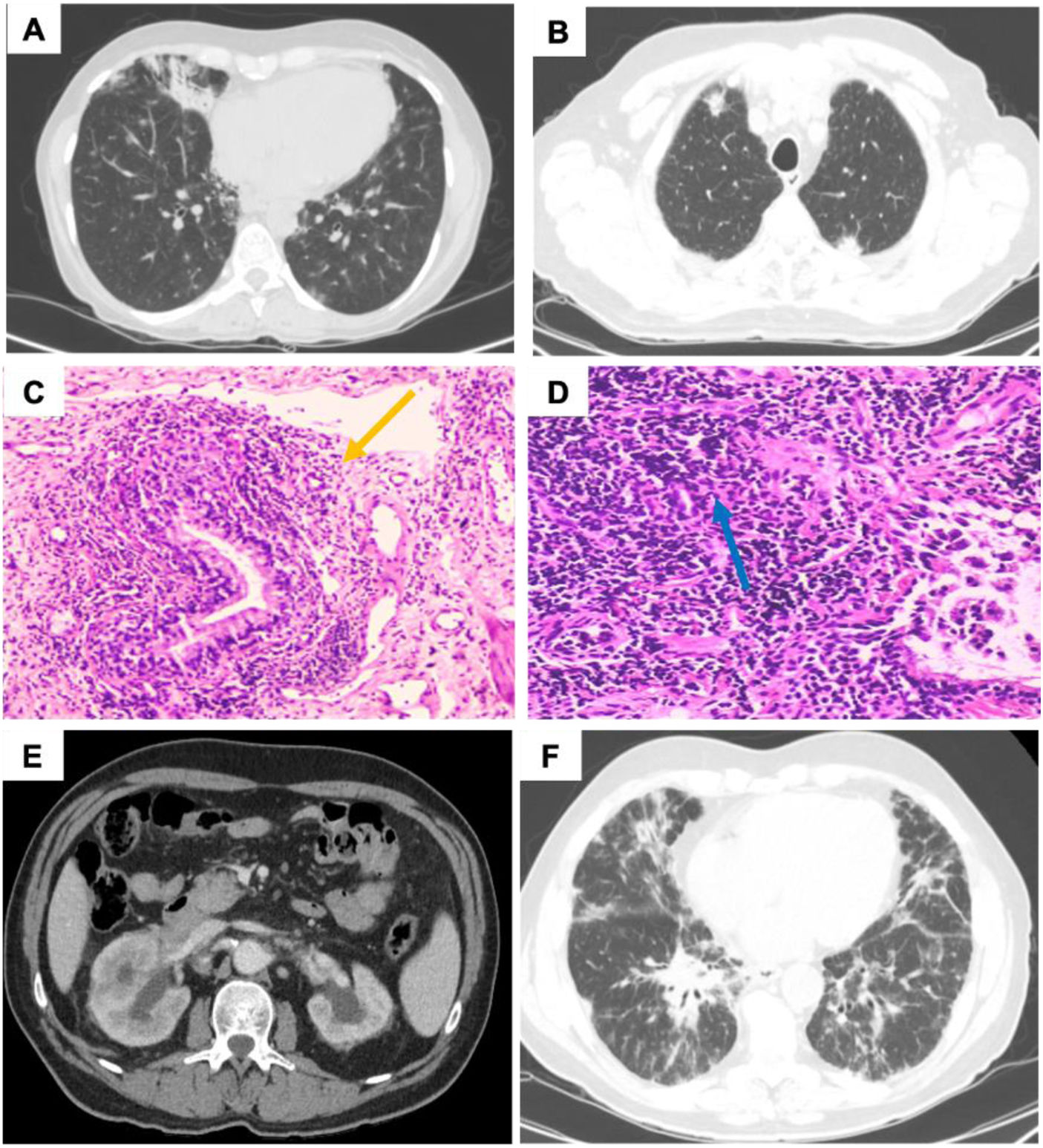

(A) Reticulonodular pattern in both lung bases. (B) Nodular lesions. (C) Peribronchial lymphocytic infiltrate (yellow arrow). (D) Bronchiolar structures are surrounded by a lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate (blue arrow). (E) Left kidney with thinning of the parenchyma with pyelocaliceal ectasia, suggesting chronic etiology. Adenopathies adjacent to both renal hili. (F) Interstitial pattern of the glass, with the addition of areas of ground glass.

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) was diagnosed and prednisone was administered (60mg/day in a descending pattern), after which both ITP and respiratory symptoms improved. A transbronchial biopsy was performed and histopathology revealed the presence of a lymphoid infiltrate (Fig. 1C and D). The immunological study detected IgA and IgG deficiency, so he was diagnosed with Granulomatous lymphocytic interstitial lung disease (GLILD) as complication of common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). Inhaled therapy was withdrawn, treatment was started with intravenous gamma globulin, prednisone (40mg/day in descending doses) and azathioprine (2mg/day), the latter two being suspended after two years of clinical–radiological stability.

One year after discontinue immunosuppressants, the patient consulted for anuria and hypogastric pain. Laboratory tests showed deterioration of renal function (creatinine 2.1mg/dL and glomerular filtration rate 49mL/min/m2). Abdominopelvic ultrasound showed bilateral obstructive uropathy (BOU). Multislice CT urography confirmed BOU, and showed the presence of lymphadenopathy as a cause of this obstruction (Fig. 1E). A bilateral double J catheter was placed and a CT-body scan was performed showing lymphadenopathy at different levels. As well as worsening of the pulmonary interstitial pattern (Fig. 1F). Core needle biopsy of cervical lymphadenopathy was performed, and the pathology study was compatible with nodular lymphocytic Hodgkin's lymphoma.

GLILD is a complication of CVID, it usually presents as recurrent respiratory infections, with radiological–anatomopathological changes compatible with granulomatous disease. It can also mimic the behavior of other respiratory disorders (e.g., sarcoidosis, organizing pneumonia, etc.).1 However, it is unusual for GLILD to mimic the clinical features of asthma. It should be noted that the symptomatology itself is nonspecific and that in approximately 20% of cases GLILD may have an obstructive spirometry.2 Although it can also present with a restrictive or mixed pattern.1,2 But the lack of response to inhaled therapy and the fact that the patient had already presented two cases of pneumonia in less than a year changed the diagnostic orientation. Therefore, the immunological study is a key diagnostic test. Patients with CVID may develop ITP and lymphoproliferative syndromes. Although the exact cause of the latter is unknown, it is theorized that the immune disorder itself and repeated infections may be responsible for the disorder.3 Of the reported cases of GLILD, there is only one published case where this disease has come to mimic the pattern of bronchial asthma. Thus, this illustrates the importance of reevaluating pulmonary symptomatology that does not respond to standard therapies. And that this unusual pathology should be considered as a differential diagnosis.

Informed consentThe authors have obtained the informed consent of the patients and/or subjects referred to in the article. This document is held by the corresponding author.

FundingThis research has not received any specific grants from agencies in the public, commercial or for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors have made substantial contributions in each of the following aspects: (1) data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, (2) drafting of the article (3) and final approval of the version presented.

Conflicts of interestThe authors state that they have no conflict of interests.