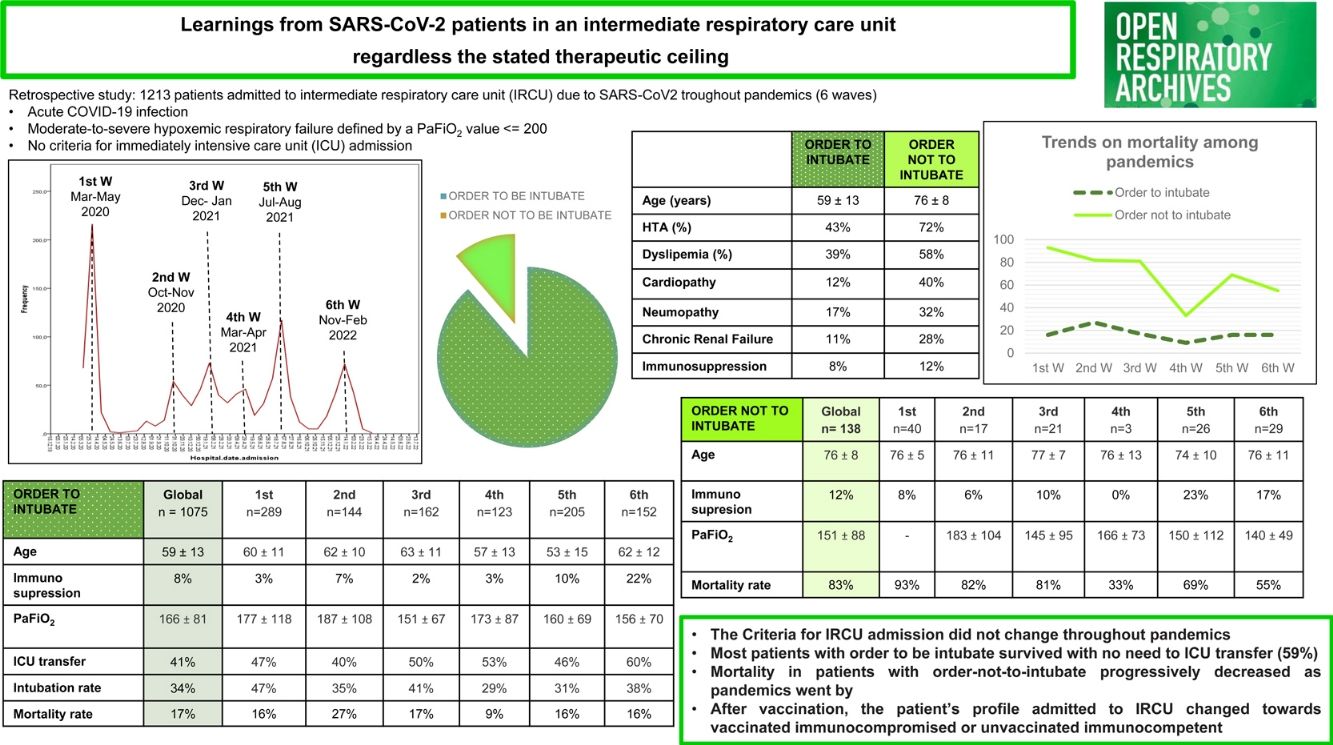

Soon after the first outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy on February 2020,1 the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic spread rapidly through Europe. At that time, COVID-19 disease was a serious worldwide threat and many strategies were implemented to get over this challenge.2,3 From initial strict lockdowns to lesser social distancing measures once vaccination started; from extensive use of antiviral drugs to more target treatments based on the phase of the disease, respiratory support depending on clinical condition and dynamic healthcare restructuring capacity. At the beginning, healthcare resources were focused primarily on patients with the highest possibility of survival.4,5 Afterwards, it was possible to balance efforts also for patients on therapeutic ceiling. In Spain, the vaccination campaign began in December 2020. Vaccination was prioritized in certain population groups (elderly individuals, dependents and frontline health workers) and progressively achieved systematic vaccination towards July 20216 (towards fifth wave). The aim of the study was to analyze the trends in intra-hospital management through COVID pandemic in severe SARS-CoV-2 patients admitted to our intermediate respiratory care unit (IRCU), specially depending on the stablished therapeutic ceiling.

We conducted a retrospective study including patients admitted to a Tertiary Hospital's IRCU from March 2020 to March 2022. The final follow-up date was 28-June-2022. The local ethics committee of the institution approved the study protocol (PR260/20). Due to the potential infective situation, patients gave oral not-written informed consent. Inclusion criteria: 1. Acute COVID-19 infection (positive polymerase chain reaction for SARS-CoV-2 from nasopharyngeal swab at admission); 2. Clinical signs of pneumonia (fever, cough, dyspnea); 3. Hypoxemic respiratory failure defined by oxygen saturation measured by pulse-oximeter (SaO2) ≤94% with supplementary oxygen with fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2), SaFiO2 >50% and/or a ratio of arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) to FiO2 (PaFiO2) <200. Exclusion criteria: (1) Criteria for direct ICU admission (imminent intubation, hemodynamic instability, multiorgan failure, abnormal mental status and shock). Demographical, comorbidities, vaccine status, clinical and laboratory data were collected. Data regarding noninvasive respiratory therapy (NRT), systemic corticosteroid therapy and statistical analysis were explained at previous work.7

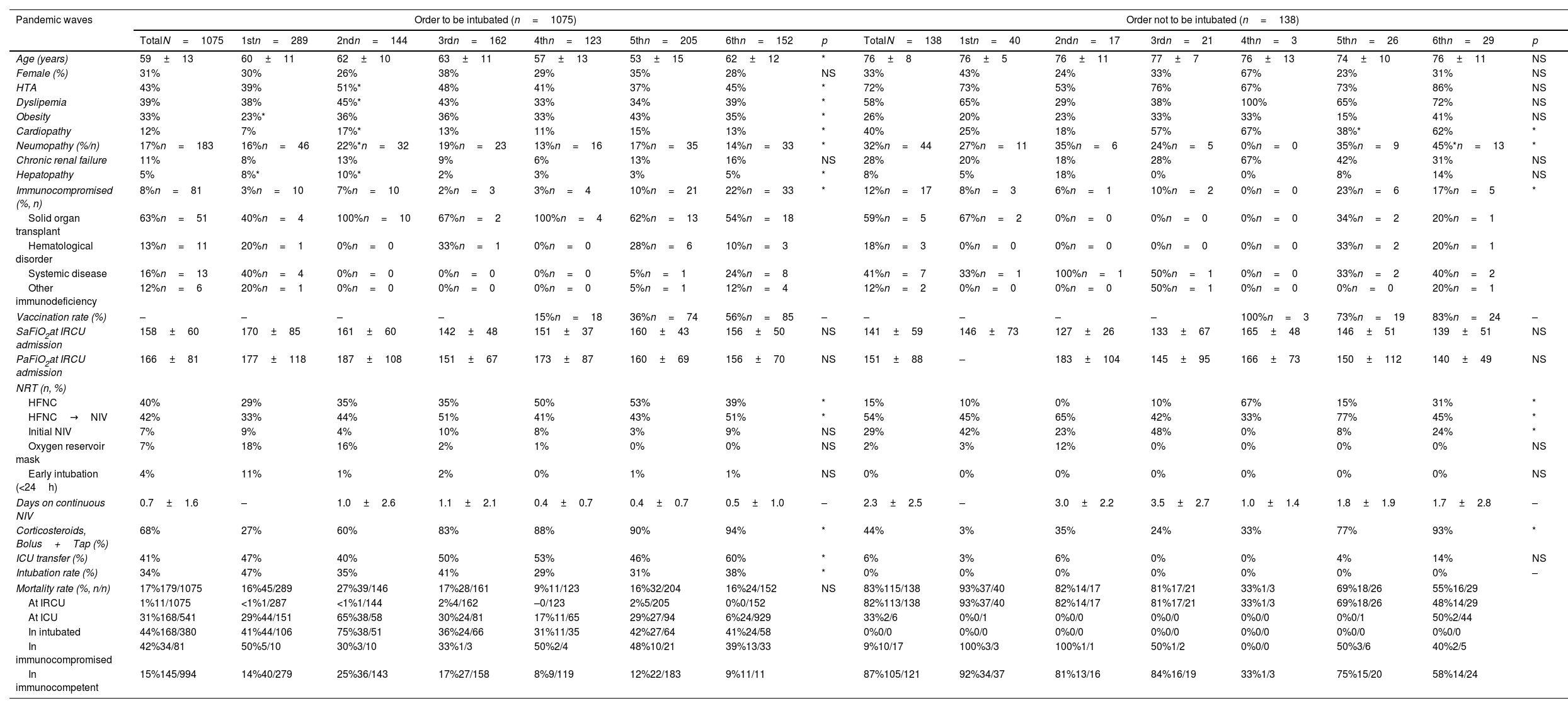

Table 1 illustrates main data where up to 59% of patients (645/1075) were treated at IRCU with no need to ICU transfer.

Main results of patients with SARS-CoV-2 admitted to Bellvitge's IRCU based on limitation of therapeutic effort though pandemic waves.

| Pandemic waves | Order to be intubated (n=1075) | Order not to be intubated (n=138) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TotalN=1075 | 1stn=289 | 2ndn=144 | 3rdn=162 | 4thn=123 | 5thn=205 | 6thn=152 | p | TotalN=138 | 1stn=40 | 2ndn=17 | 3rdn=21 | 4thn=3 | 5thn=26 | 6thn=29 | p | |

| Age (years) | 59±13 | 60±11 | 62±10 | 63±11 | 57±13 | 53±15 | 62±12 | * | 76±8 | 76±5 | 76±11 | 77±7 | 76±13 | 74±10 | 76±11 | NS |

| Female (%) | 31% | 30% | 26% | 38% | 29% | 35% | 28% | NS | 33% | 43% | 24% | 33% | 67% | 23% | 31% | NS |

| HTA | 43% | 39% | 51%* | 48% | 41% | 37% | 45% | * | 72% | 73% | 53% | 76% | 67% | 73% | 86% | NS |

| Dyslipemia | 39% | 38% | 45%* | 43% | 33% | 34% | 39% | * | 58% | 65% | 29% | 38% | 100% | 65% | 72% | NS |

| Obesity | 33% | 23%* | 36% | 36% | 33% | 43% | 35% | * | 26% | 20% | 23% | 33% | 33% | 15% | 41% | NS |

| Cardiopathy | 12% | 7% | 17%* | 13% | 11% | 15% | 13% | * | 40% | 25% | 18% | 57% | 67% | 38%* | 62% | * |

| Neumopathy (%/n) | 17%n=183 | 16%n=46 | 22%*n=32 | 19%n=23 | 13%n=16 | 17%n=35 | 14%n=33 | * | 32%n=44 | 27%n=11 | 35%n=6 | 24%n=5 | 0%n=0 | 35%n=9 | 45%*n=13 | * |

| Chronic renal failure | 11% | 8% | 13% | 9% | 6% | 13% | 16% | NS | 28% | 20% | 18% | 28% | 67% | 42% | 31% | NS |

| Hepatopathy | 5% | 8%* | 10%* | 2% | 3% | 3% | 5% | * | 8% | 5% | 18% | 0% | 0% | 8% | 14% | NS |

| Immunocompromised (%, n) | 8%n=81 | 3%n=10 | 7%n=10 | 2%n=3 | 3%n=4 | 10%n=21 | 22%n=33 | * | 12%n=17 | 8%n=3 | 6%n=1 | 10%n=2 | 0%n=0 | 23%n=6 | 17%n=5 | * |

| Solid organ transplant | 63%n=51 | 40%n=4 | 100%n=10 | 67%n=2 | 100%n=4 | 62%n=13 | 54%n=18 | 59%n=5 | 67%n=2 | 0%n=0 | 0%n=0 | 0%n=0 | 34%n=2 | 20%n=1 | ||

| Hematological disorder | 13%n=11 | 20%n=1 | 0%n=0 | 33%n=1 | 0%n=0 | 28%n=6 | 10%n=3 | 18%n=3 | 0%n=0 | 0%n=0 | 0%n=0 | 0%n=0 | 33%n=2 | 20%n=1 | ||

| Systemic disease | 16%n=13 | 40%n=4 | 0%n=0 | 0%n=0 | 0%n=0 | 5%n=1 | 24%n=8 | 41%n=7 | 33%n=1 | 100%n=1 | 50%n=1 | 0%n=0 | 33%n=2 | 40%n=2 | ||

| Other immunodeficiency | 12%n=6 | 20%n=1 | 0%n=0 | 0%n=0 | 0%n=0 | 5%n=1 | 12%n=4 | 12%n=2 | 0%n=0 | 0%n=0 | 50%n=1 | 0%n=0 | 0%n=0 | 20%n=1 | ||

| Vaccination rate (%) | – | – | – | – | 15%n=18 | 36%n=74 | 56%n=85 | – | – | – | – | – | 100%n=3 | 73%n=19 | 83%n=24 | – |

| SaFiO2at IRCU admission | 158±60 | 170±85 | 161±60 | 142±48 | 151±37 | 160±43 | 156±50 | NS | 141±59 | 146±73 | 127±26 | 133±67 | 165±48 | 146±51 | 139±51 | NS |

| PaFiO2at IRCU admission | 166±81 | 177±118 | 187±108 | 151±67 | 173±87 | 160±69 | 156±70 | NS | 151±88 | – | 183±104 | 145±95 | 166±73 | 150±112 | 140±49 | NS |

| NRT (n, %) | ||||||||||||||||

| HFNC | 40% | 29% | 35% | 35% | 50% | 53% | 39% | * | 15% | 10% | 0% | 10% | 67% | 15% | 31% | * |

| HFNC→NIV | 42% | 33% | 44% | 51% | 41% | 43% | 51% | * | 54% | 45% | 65% | 42% | 33% | 77% | 45% | * |

| Initial NIV | 7% | 9% | 4% | 10% | 8% | 3% | 9% | NS | 29% | 42% | 23% | 48% | 0% | 8% | 24% | * |

| Oxygen reservoir mask | 7% | 18% | 16% | 2% | 1% | 0% | 0% | NS | 2% | 3% | 12% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | NS |

| Early intubation (<24h) | 4% | 11% | 1% | 2% | 0% | 1% | 1% | NS | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | NS |

| Days on continuous NIV | 0.7±1.6 | – | 1.0±2.6 | 1.1±2.1 | 0.4±0.7 | 0.4±0.7 | 0.5±1.0 | – | 2.3±2.5 | – | 3.0±2.2 | 3.5±2.7 | 1.0±1.4 | 1.8±1.9 | 1.7±2.8 | – |

| Corticosteroids, Bolus+Tap (%) | 68% | 27% | 60% | 83% | 88% | 90% | 94% | * | 44% | 3% | 35% | 24% | 33% | 77% | 93% | * |

| ICU transfer (%) | 41% | 47% | 40% | 50% | 53% | 46% | 60% | * | 6% | 3% | 6% | 0% | 0% | 4% | 14% | NS |

| Intubation rate (%) | 34% | 47% | 35% | 41% | 29% | 31% | 38% | * | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | – |

| Mortality rate (%, n/n) | 17%179/1075 | 16%45/289 | 27%39/146 | 17%28/161 | 9%11/123 | 16%32/204 | 16%24/152 | NS | 83%115/138 | 93%37/40 | 82%14/17 | 81%17/21 | 33%1/3 | 69%18/26 | 55%16/29 | |

| At IRCU | 1%11/1075 | <1%1/287 | <1%1/144 | 2%4/162 | –0/123 | 2%5/205 | 0%0/152 | 82%113/138 | 93%37/40 | 82%14/17 | 81%17/21 | 33%1/3 | 69%18/26 | 48%14/29 | ||

| At ICU | 31%168/541 | 29%44/151 | 65%38/58 | 30%24/81 | 17%11/65 | 29%27/94 | 6%24/929 | 33%2/6 | 0%0/1 | 0%0/0 | 0%0/0 | 0%0/0 | 0%0/1 | 50%2/44 | ||

| In intubated | 44%168/380 | 41%44/106 | 75%38/51 | 36%24/66 | 31%11/35 | 42%27/64 | 41%24/58 | 0%0/0 | 0%0/0 | 0%0/0 | 0%0/0 | 0%0/0 | 0%0/0 | 0%0/0 | ||

| In immunocompromised | 42%34/81 | 50%5/10 | 30%3/10 | 33%1/3 | 50%2/4 | 48%10/21 | 39%13/33 | 9%10/17 | 100%3/3 | 100%1/1 | 50%1/2 | 0%0/0 | 50%3/6 | 40%2/5 | ||

| In immunocompetent | 15%145/994 | 14%40/279 | 25%36/143 | 17%27/158 | 8%9/119 | 12%22/183 | 9%11/11 | 87%105/121 | 92%34/37 | 81%13/16 | 84%16/19 | 33%1/3 | 75%15/20 | 58%14/24 | ||

Abbreviations: IRCU, intermediate respiratory care unit; HTA, systemic arterial hypertension; SaFiO2, the value of oxygen saturation measured by pulse-oximeter (SaO2) divided by the value of fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2) required at IRCU admission; PaFiO2, the value of arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2 in mmHg) measured by the arterial blood gas analysis divided by the value of fractional inspired oxygen (FiO2) required at IRCU admission; NRT, non-invasive respiratory therapy; HFNC, high flow nasal cannula; NIV, non-invasive ventilation (NIV); ICU, intensive care unit.

In patients with no therapeutic ceiling, mortality across the first four waves was slightly modified. A percentage of fatal cases (≈16–9%) occurred although maximally optimized management. That is relevant since IRCU admission's criteria were not modified given that PaFiO2 and SaFiO2 mean ratios at IRCU admission did not increase as the pandemic went by. During the second wave, the mortality was even higher. At that time, a nosocomial outbreak emerged, infecting many kidney transplant patients and patients with heart failure who were admitted for other medical reasons, probably explaining this increase. During the first month when there was not enough NRT devices, many patients were on oxygen-reservoir mask or received early intubation. Fortunately, afterwards we could treat properly patients optimizing ICU beds. From the second wave on, percentages of use of different NRT did not vary significantly. HFNC was the most administered followed by sequential strategy (HFNC→NIV). Patients on initial NIV were a minority stable group. As pandemics go through, the mean time on continuous NIV shortens since intubation delay was clearly detrimental after ≥48h on continuous NIV. The corticosteroids use progressively increased. Our team strongly support this strategy even before Recovery trial was published.8 Almost all (99%) died at ICU reflecting an appropriate ICU beds availability. Patients admitted during second wave were more comorbid and those during first wave less obese. The percentage of immunosuppressive patients was higher during 5th and 6th waves in parallel with the change on patient's profile observed after vaccination. Solid organ transplant (SOT) was the most prevalent immunosuppressive condition. Dead patients were older, more comorbid and more baseline immunosuppressed (data not shown). Mortality in immunosuppressive patients was near 3-fold higher than in immunocompetent patients (42% vs 15%). In line with previous works,9 mortality was significantly higher in SOT than in others immunocompromised patients regardless wave admission and vaccine status: 57% for SOT (29/51), 9% for hematological (1/11) and 31% for systemic disease's patients (4/13). Any patient with other immunosuppressive conditions (n=6) died. Mortality did not differ between pre- and post-vaccination periods despite all were well-vaccinated during 5th and 6th waves (41% vs 43%). Respect SOT patients, mortality neither differ before and after vaccine implementation (50% vs 61%) probably reflecting their higher attenuated response to vaccination.10 Respect non-SOT, one patient died at first wave (25%, 1/4) and four well-vaccinated during the last two waves (22%, 4/18).

In patients admitted with NRT as maximal therapeutic ceiling, the mortality along the first four waves (before vaccine) progressively reduced. Many reasons could explain this fact: our better understanding to handle the disease choosing the most appropriate NRT and medical strategies, gained experience to foresee predictable problems and to focus on actions with benefit avoiding those with null or little benefit. Positive actions as combined instead of sequential NRT, maintaining enteral nutrition instead of parenteral nutrition and facilitating familiar–social digital interaction during NIV discontinuation. Taking into account the limitation of the fourth wave due to its small size (n=3), no significant differences were found on comorbidities among waves except that immunosuppressive baseline conditions were more prevalent in patients admitted during last waves. Systemic disease was the most prevalent immunosuppressive factor. Dead patients had worse hypoxia and inflammatory profiles at IRCU admission and many of them deceased during the first wave; conversely, no statistically differences were found on comorbidities and immunosuppression conditions (data not shown in the table). Mortality in immunocompetent patients was of 87%, where 63% were admitted during pre-vaccine period and many of them had severe or very severe SARS-CoV-2 plus extreme frailty and multiple comorbidities that mainly contribute to these bad outcomes. Mortality in immunosuppressive patients, all updated vaccinated, was of 59% (10/17). Relative mortality rates were: 100% for SOT, 67% for hematological and 33% for systemic disease's patients. In SOT patients, mortality neither differ before and after vaccine period (100% in both periods). In other immunosuppressive conditions, mortality was reduced: among hematological patients (100%→50%) and among systemic disease's patients (67%→17%). Although limited data in these subgroups, the survival improvement could be related to the vaccine's effectiveness in non-SOT patients.

Strengths: (1) cohort assessment at the same time (initial inflammatory phase); (2) unchanged criteria for IRCU admission throughout pandemics. Limitations: (1) obesity approach by categorical data instead of body mass index values; (2) observational design does not allow to analyze whether survival may be related to better IRCU management.

Main conclusions: (1) IRCU admission's criteria for moderate-to-severe SARS-CoV-2 patients do not change throughout pandemics; (2) Most patients (59%) survive with no ICU transfer; (3) Mortality remained unchanged in patients with no therapeutic ceiling (≈16%) while progressively decrease in patients with NRT therapeutic ceiling (93%→55%); (4) Vaccination modifies the patient's profile making vaccinated immunocompromised patients the most vulnerable ones.

As final consideration, the pandemic has provided an unequalled learning to be better qualified for future pandemics. The benefit of this learning was initially aimed to patients with no therapeutic ceiling; after the first wave, this benefit extended in those with stablished NRT therapeutic ceiling.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributionsYRA, EC, GSC, ACI, MS, SS and MG take care of medical management of the patients; MP, PC and CB collected and entry all variables in the database. MG and MP analyzed data. All authors interpreted and discussed the results. MP and MG wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the final version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare not to have any conflicts of interest that may influence directly or indirectly the content of the manuscript.

The authors are grateful to all healthcare workers that extended their unconditional support taking care of the patients admitted to Bellvitge's IRCU during pandemics.