There are different forms of invasive tracheobronchial aspergillosis (ITBA), namely “plain” tracheobronchitis, ulcerative tracheobronchitis, and pseudomembranous tracheobronchitis (PT), being the latter the most severe condition. These entities are more often described in bone marrow as well as in lung and other solid organ transplant recipients. They also appear in hematologic and solid organ cancers, and in AIDS. It is rare for some forms of ITBA to be reported in mildly immunocompromised hosts, such as in those with severe COPD, other chronic lung diseases, or diabetes mellitus. Additionally, ITBA has been linked to the intake of systemic corticosteroids and broad-spectrum antibiotics.1–7 The clinical presentation can be wide-ranging, from chronic dry cough and anorexia to high fever, severe respiratory distress, and rapid development of respiratory and multiorgan failure. The chest x-ray might be non-revealing, although ITBA more frequently coexists with pulmonary infiltrates, such as in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Visual inspection by bronchoscopy shows cream-colored necrotic tissue throughout the trachea and endobronchial biopsy will demonstrate mucosal invasion by the fungi. The prognosis largely depends on the degree of fungal invasion and the underlying disease. Concerning medical therapy, the expert consensus recommends a combination of inhaled amphotericin B plus systemic voriconazole or amphotericin.1,3,8

We present a 49-year-old woman, ex-smoker – 20 packs-year–, with recurrent episodes of rhinosinusitis. Her history also includes discrete bronchiectasis in the lower lobes and the right middle lobe. She was the mother of a child delivered after an uneventful pregnancy. In the previous two years, she had visited the emergency room (ER) several times because of bouts of acute bronchitis, and had been admitted twice. Notably, the sputum cultures grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Nocardia cyriacigeorgica on separate occasions, with a negative workup for widespread infection. She received targeted treatments for these bacteria. During an outpatient visit, the pulmonary function tests revealed a negative response to inhaled salbutamol, with the following results: FEV1: 1.9 l. (76% pred.), FVC: 2.8 l. (84% pred.), FEV1/FVC: 67%, TLC: 4.7 l. (116% pred.), RV: 1.8 l. (163% pred.), TLCO: 64% pred., and KCO: 69% pred. A diagnosis of grade 2B COPD according to GOLD classification was established. The etiologic work-up for the associated bronchiectasis reported normal levels of total IgG and IgG subtypes, IgA and IgM; normal sweat chloride level (12mmol/l); absence of ultrastructural abnormalities in the cilia of bronchial epithelium, and negative human immunodeficiency virus HIV serology. Only total IgE was high, 720UI/ml (20–87). Lastly, the serum level of alpha-1 antitrypsin was within normal limits and so were serum ANA, rheumatoid factor, and citrullinated peptide antibodies.

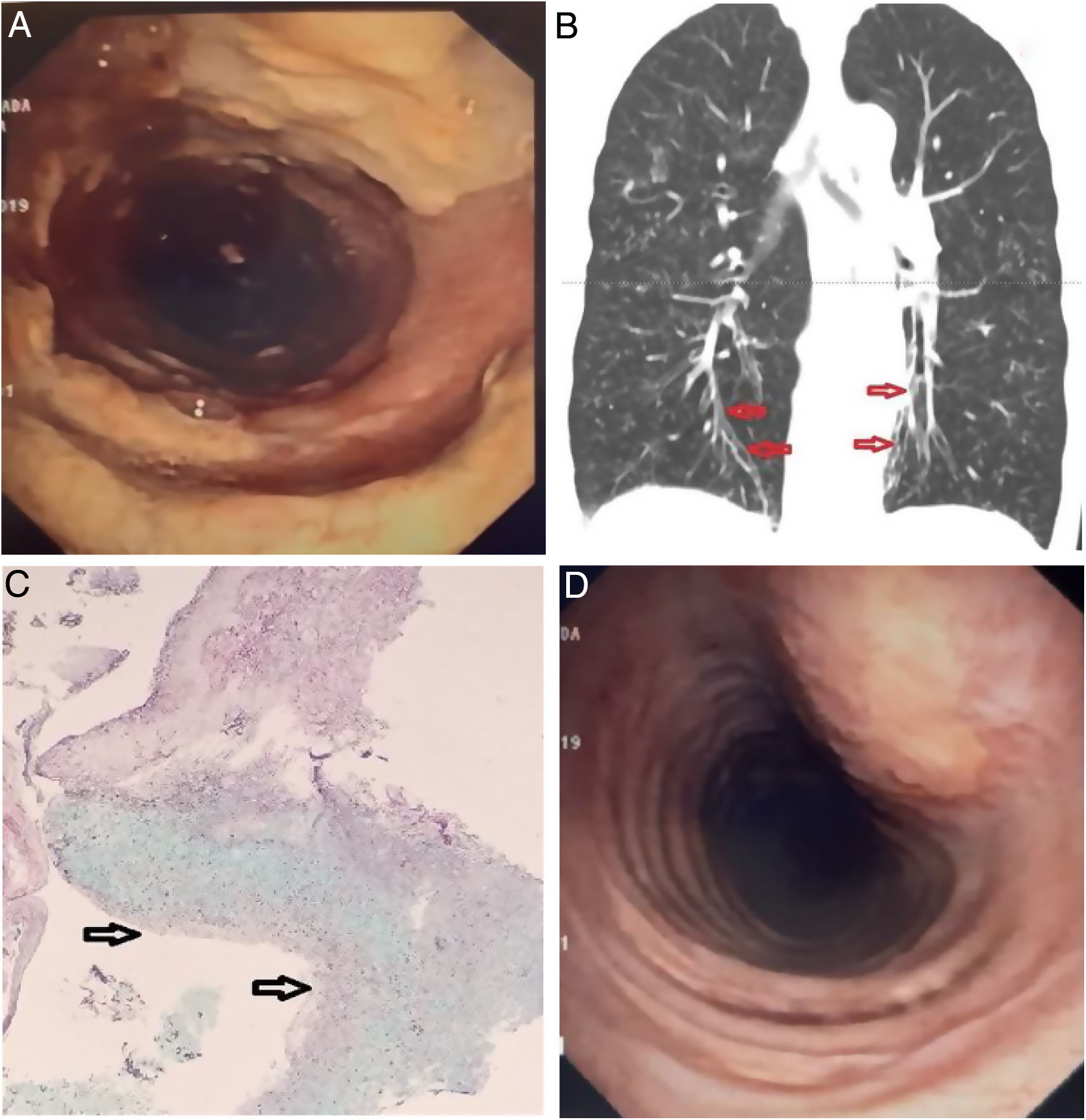

The patient visited the ER complaining of cough with purulent sputum, facial pain, rhinorrea, and loss of appetite. She reported a baseline grade II over IV dyspnea on the MRC scale that had recently worsened. Regular home treatment included twice daily 1 Million IU of nebulized colistin, inhaled fluticasone/formoterol and tiotropium. The physical examination revealed a slender woman in no respiratory distress, with reproducible pain over the frontal and maxillary sinuses, and scattered inspiratory crackles with diffuse expiratory rhonchi. She had no clubbing of the fingertips. Room air PaO2 was 58mm Hg with normal PaCO2, and a whole blood count showed 14×103leukocytes/μl with 7% eosinophils. The chest X-ray showed increased diffuse bronchovascular markings and discrete signs of lung hyperinflation. Nasopharyngeal rapid PCR for influenza A and B was negative. Sputum samples were sent for culture, and IV ceftazidime plus tobramycin, and oral prednisone were started. However, only Aspergillus fumigatus was repeatedly isolated. Her facial pain improved but the sputum remained purulent, followed by an episode of moderate hemoptysis and oxygen desaturation that was corrected with low flow oxygen. At that point, the oral corticosteroid was interrumpted and a fiberoptic bronchoscopy was carried out. Unexpectedly, the endoscopic examination showed diffuse non-obstructing yellowish plaques in the trachea and proximal right main bronchus (Fig. 1A), and fresh blood oozing from the right upper posterior segment. A representative image of the CT is shown (Fig. 1B). A slide from the biopsy of bronchial mucosa is presented (Fig. 1C).

(A) Endoscopic view of the trachea. Coarse, yellowish plaques and friable mucosa interspersed with areas of normal mucosa. (B) CT scan, coronal view: Discrete varicose bronchiectasis are visible in the lower lobes (arrows). Signs of diffuse cellular bronchiolitis are evident, and no lung infiltrates were noted. (C) Histologic examination of a pseudomembrane. Submucosal inflammation with a dense eosinophilic infiltrate due to the presence of fungi is appreciated (the arrows point to the bronchial lumen). (D) Repeat bronchoscopy after three weeks of treatment showed marked improvement of the lesions.

Serum galactomannan and precipitins to Aspergillus fumigatus were not detectable. The administration of antibiotics was interrupted, and IV voriconazole plus nebulized liposomal amphotericin B were given for four weeks. See Fig. 1D. At that point, the patient had made a good recovery with abatement of bronchorrhea and hemoptysis as well as amelioration in dyspnea and arterial oxygenation. Three months later, repeated measurements of peripheral eosinophils and immunoglobulins were within normal limits, and extensive characterization of the immunophenotype, as well as phagocytic activity and the oxidative burst test of monocytes and polymorphonuclear neutrophils were found to be normal.

ITBA and nocardiosis have been reported in COPD patients, but older subjects with severe disease, considered mildly immunocompromised, are the usual hosts.2,4,8,9 Local damage of the airway wall and non-fungal infections may be predisposing factors for ITBA. In this respect, we cannot rule out whether inhaled colistin predisposed to colonization and subsequent infection by the fungus. Such association is rare, but nonetheless described in the non-CF bronchiectasis population.10 The increased total IgE and high eosinophil count soon after admission were interpreted as markers of a hypersensitivity reaction to the fungus. However, the criteria for allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis were not fulfilled.

The present case depicts a for-all purpose immunocompetent patient with moderate COPD and discrete bronchiectasis who presents with recurrent opportunistic respiratory infections typical of the immunodeficient host. However, ITBA has also been described in immunocompetent patients.4,11–13 It is important to note that unilateral involvement of the bronchial tree in PT has been communicated.8 PT is the most severe form of ITBA and is usually fatal despite treatment with antifungal agents. However, the condition can be successfully treated in non-severely immunocompromised patients. In the present case, the response to antifungal treatment was favorable, and the patient remained free of opportunistic infections during the subsequent year. This case reminds us that the isolation of Aspergillus from noninvasive respiratory samples in a patient with structural lung disease should not be dismissed as a contaminant.14