Despite the fact that endobronchial ultrasound-fine needle aspiration (EBUS-FNA) is a common technique with a high safety profile,1 it is not exempt from severe morbidity and mortality, such as, for example, purulent pericarditis (PP).2 We report a case that occurred in our center and review the complications encountered over a year.

A 66-year-old male patient, former-smoker for 35 years (40cigarettes/day), was referred to the pulmonology rapid diagnostic unit for the study of a paratracheal mass suspected of malignancy. His medical history included benign prostatic hyperplasia, dyslipidemia, anxiety-depressive syndrome, obesity, hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and colonic polyposis. An EBUS-FNA was performed on stations 4L (17.1mm×6.8mm) with 2 passes and 4R (29.3mm×17.8mm) with 3 passes. The procedure was carried out with a 21G needle under sedation with propofol and fentanyl. Rapid On-Site Evaluation (ROSE) was conducted, and the 4R lymph node station suspected of malignancy was diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma PDL<1%, stage IIIB (T3N2M0). The procedure was carried out without immediate complications.

Five days later, the patient presented to the emergency department with non-radiating, sharp, non-oppressive central chest pain associated with moderate exertion dyspnea and a fever spike. Blood tests showed elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) (13.7mg/dL) and leukocytosis with a left shift (12.4×10*9/L), and the chest X-ray did not reveal any acute pleuropulmonary pathology. Outpatient treatment with cefditoren 400mg for 5 days was initiated without improvement. One week later, the patient returned due to persistent dyspnea and edema with oliguria, alongside worsening laboratory results (CRP>41mg/dL, leukocytes 19×10*9/L, and creatinine 7mg/dL). The ECG showed sinus tachycardia with decreased voltages, a 1cm ST elevation in leads I and AVL and flattened/negative T waves in the inferior leads, prompting an echocardiogram and admission to the ICU for cardiogenic shock secondary to cardiac tamponade, requiring pericardiocentesis. The final diagnosis was PP, and empirical antibiotic treatment with amoxicillin–clavulanic acid was started while awaiting definitive microbiological results. Streptococcus anginosus and Granulicatella adiacens were isolated from the pericardial fluid culture, and treatment started with ceftriaxone monotherapy. The patient's condition did not improve, and he developed constrictive pericarditis that required surgical debridement.

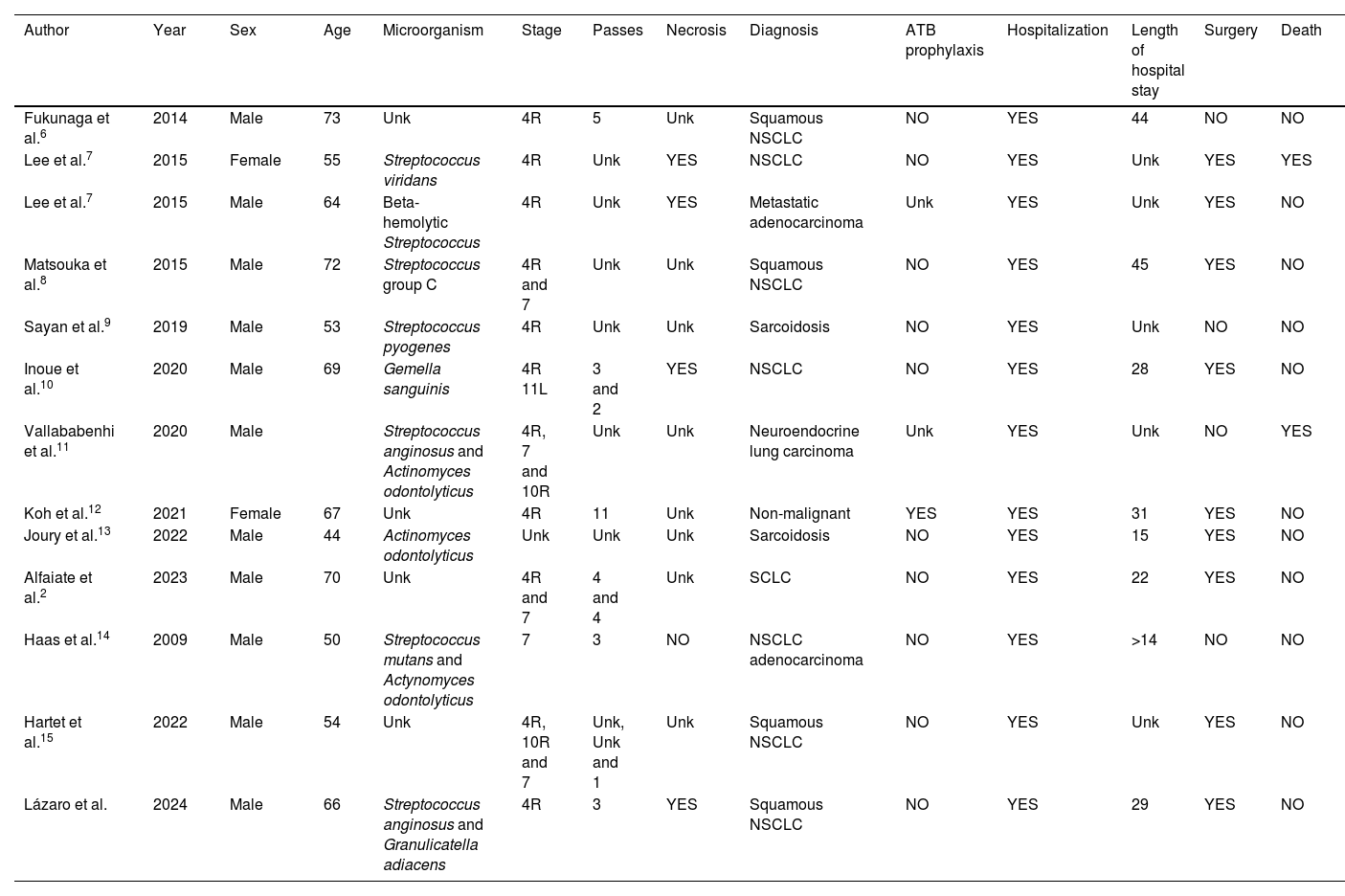

Infection is the most common complication of EBUS-FNA,3 yet pericarditis is very rare, with few cases reported in the literature, as shown in Table 1. Reports identify necrosis on computed tomography, extraction of >10 lymph node samples, immunosuppression, and the esophageal route as potential risk factors for developing infectious complications.4 The presumed mechanism of infection is the transfer of oropharyngeal bacteria (as in our case) to the mediastinal tissue during puncture.5

Literature review of cases of purulent pericarditis following endobronchial ultrasound-fine needle aspiration.

| Author | Year | Sex | Age | Microorganism | Stage | Passes | Necrosis | Diagnosis | ATB prophylaxis | Hospitalization | Length of hospital stay | Surgery | Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fukunaga et al.6 | 2014 | Male | 73 | Unk | 4R | 5 | Unk | Squamous NSCLC | NO | YES | 44 | NO | NO |

| Lee et al.7 | 2015 | Female | 55 | Streptococcus viridans | 4R | Unk | YES | NSCLC | NO | YES | Unk | YES | YES |

| Lee et al.7 | 2015 | Male | 64 | Beta-hemolytic Streptococcus | 4R | Unk | YES | Metastatic adenocarcinoma | Unk | YES | Unk | YES | NO |

| Matsouka et al.8 | 2015 | Male | 72 | Streptococcus group C | 4R and 7 | Unk | Unk | Squamous NSCLC | NO | YES | 45 | YES | NO |

| Sayan et al.9 | 2019 | Male | 53 | Streptococcus pyogenes | 4R | Unk | Unk | Sarcoidosis | NO | YES | Unk | NO | NO |

| Inoue et al.10 | 2020 | Male | 69 | Gemella sanguinis | 4R 11L | 3 and 2 | YES | NSCLC | NO | YES | 28 | YES | NO |

| Vallababenhi et al.11 | 2020 | Male | Streptococcus anginosus and Actinomyces odontolyticus | 4R, 7 and 10R | Unk | Unk | Neuroendocrine lung carcinoma | Unk | YES | Unk | NO | YES | |

| Koh et al.12 | 2021 | Female | 67 | Unk | 4R | 11 | Unk | Non-malignant | YES | YES | 31 | YES | NO |

| Joury et al.13 | 2022 | Male | 44 | Actinomyces odontolyticus | Unk | Unk | Unk | Sarcoidosis | NO | YES | 15 | YES | NO |

| Alfaiate et al.2 | 2023 | Male | 70 | Unk | 4R and 7 | 4 and 4 | Unk | SCLC | NO | YES | 22 | YES | NO |

| Haas et al.14 | 2009 | Male | 50 | Streptococcus mutans and Actynomyces odontolyticus | 7 | 3 | NO | NSCLC adenocarcinoma | NO | YES | >14 | NO | NO |

| Hartet et al.15 | 2022 | Male | 54 | Unk | 4R, 10R and 7 | Unk, Unk and 1 | Unk | Squamous NSCLC | NO | YES | Unk | YES | NO |

| Lázaro et al. | 2024 | Male | 66 | Streptococcus anginosus and Granulicatella adiacens | 4R | 3 | YES | Squamous NSCLC | NO | YES | 29 | YES | NO |

ATB: antibiotic; Unk: unknown; NSCLC: non-small cell lung cancer; SCLC: small cell lung cancer.

In the review of published cases, a total of 16 lymph node stations were punctured, 11 of 16 (68.75%) being station 4R and 4 of 16 (25%) of the subcarinal station. In one case, station 11L was analyzed, though station 4R had also been biopsied. Similar to most reviewed cases, station 4R was punctured in our case. This lymph node station, along with the subcarinal station, has anatomical relationships with the pericardium that can explain the development of PP.

The pericardium has 2 layers, visceral and parietal, similar to the pleura. Both continue with each other at the pericardial reflection points, forming openings for the large vessels. These areas are known as pericardial recesses and are located in 2 well-differentiated sinuses: the transverse sinus and the oblique sinus. The former houses the exit of the aorta and pulmonary trunk, while the superior aortic recesses (SAR) are divided into anterior (aSAR), inferior (iSAR), and posterior (pSAR); aSAR relates to the prevascular space, iSAR is situated between the aorta exit, the pulmonary trunk, and the arrival of the superior vena cava, and pSAR relates to the structures in the right lower paratracheal space, corresponding to station 4R. The oblique sinus is the pericardial reflection point where all veins, including the cava vein and pulmonary arteries, enter. Its uppermost point is proximally related to the fat of the subcarinal space, where station 7 is located.

In this context, we retrospectively reviewed the development of complications in the first 30 days after tests performed in our unit during 2023. A total of 120 EBUS-FNA procedures with ROSE technique were performed, in which 182 lymph nodes were analyzed with a total of 605 passes. Stations 7 and 4R were the most frequently analyzed; 69 (37.8%) and 46 (25.3%) respectively.

There were a total of 15 (12.5%) complications (defined as any health event occurring in the first 30 days after the test and reasonably related to it), 11 (11.8%) of which were infectious (defined as seeking medical attention for fever and/or receiving antibiotic treatment) in nature (including the present case). Only 1 patient developed a complication without station 4R and/or 7 being punctured, whereas all infectious complications appeared in patients where 1 or both stations had been punctured.

In our case series, infectious complications appeared in cases with a greater number of lymph node stations and thus a higher number of passes. Although it did not reach statistical significance, it is worth noting that all infectious complications occurred when stations 4R and/or 7 were analyzed. Within the first 30 days post-procedure, 8 patients were hospitalized for complications (7 for infectious complications and 1 for pulmonary thromboembolism). Two patients (18.2%) died in the group that developed infectious complications, while another 2 patients (2%) died in the group without complications. Patient mortality was not related to the complications but to the severity of the neoplastic disease, due to the fact that patients with more advanced tumor stages are more frail and are therefore more susceptible to developing complications after an invasive procedure such as EBUS-FNA.

Post-EBUS-FNA fever occurs in up to 10% of cases and does not necessarily imply the development of a severe complication. According to Moon et al., risk factors for developing fever include age, higher number of punctures, performing lavage in the same act, suspicion of tuberculosis, anemia, or elevated CRP levels.15 This study does not take into account lymphadenopathy or the presence of necrosis. The European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends the use of prophylactic antibiotics in the case of cystic or solid lesions with necrosis, but this is not supported by other societies, as they may not penetrate avascular structures like necrotic lymph nodes.3 However, the aim of chemoprophylaxis (with antibiotics or antiseptic solution) would be to prevent bacterial translocation of oropharyngeal germs, which could be beneficial. A factor to consider regarding the prophylaxis proposed by the European Society of Gastroenterology is that in our case the procedure was not performed by the esophageal route, so the recommendation may not be valid in these cases.

Although complications of EBUS-FNA are very rare, the cost of such complications in terms of hospital stay and surgical treatment, as we have seen in the literature review, makes them a significant issue.

We conclude, therefore, that EBUS-FNA is a low-risk technique, with infectious complications being the most frequent. Lymph node stations 4R and 7 are most frequently punctured, but their close relationship with the pericardium (pSAR and oblique sinus) raises the risk of contamination and subsequent infection with potentially serious consequences, as in our patient. A multicenter study should be considered to evaluate the implementation of bacterial prophylaxis in patients undergoing analyses of stations 4R and 7, especially if they have risk factors.

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of his clinical data.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Authors’ contributionJLS participated in the planning, statistical analysis, literature review, and writing of the article; AH participated in the review of the cases and the literature review; PCM participated in the review of cases and completion of databases; BML, MASL, and SAS participated in the literature review and writing of the article.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.