Edited by: Dr. Tomás Ripollés González - Servicio de Radiodiagnóstico, Hospital Universitari Doctor Peset, València, España

More infoUltrasound is being increasingly used to study the digestive tract because it has certain advantages over other techniques such as endoscopy, CT enterography, and MR enterography. Ultrasound can be used to evaluate the bowel wall and the elements that surround it without the need for contrast agents; its ability to evaluate the elasticity and peristalsis of these structures is increasing interest in its use. This article describes the techniques and modalities of bowel ultrasound, as well as the normal features of the bowel wall and contiguous structures. It uses a practical approach to review the main pathological findings and their interpretation, and the different patterns of presentation, which will help orient the diagnosis.

El estudio del tubo digestivo con ecografía está experimentando en los últimos años un auge debido a las cualidades que tiene frente a otras técnicas como la endoscopia, la entero-TC o la entero-RM. Su capacidad de valorar la pared intestinal y elementos que la rodean sin necesidad de administración de contraste y la posibilidad de evaluar la elasticidad y peristaltismo de estas estructuras está generando un progresivo interés en su utilización. En este artículo se describe la técnica ecográfica y sus modalidades, así como las características normales de la pared intestinal y de las estructuras contiguas. Se revisan, con un enfoque práctico, los principales hallazgos patológicos y su interpretación, y los diferentes patrones de presentación, que nos aportarán una aproximación útil para orientar el diagnóstico.

Generally speaking, bowel ultrasound is a technique that has been limited to the study of the acute digestive tract in the emergency room setting, where it has proved highly useful in certain conditions such as appendicitis, acute diverticulitis, and bowel obstruction. Improved device resolution and the growing interest and experience among radiologists have made it possible to develop this technique in many other settings, such as subacute conditions and chronic diseases.

The capacity of ultrasound (similar to computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance [MR]) to evaluate transmural inflammation and alterations in the neighbouring structures is one of its main advantages compared to endoscopy. Moreover, ultrasound is a highly accessible technique that is well tolerated by patients, requires no workup and provides more details than CT in the assessment of bowel wall layers and the assessment of motility. Its limitations include difficulty in following the entire small bowel, poorer image quality in obese patients since high-frequency transducers cannot be used, and the fact that obtaining and interpreting the images depends on the operator. The learning curve is long and requires specific training, although on the other hand previous experience in abdominal ultrasound accelerates this process.

This article describes the bowel ultrasound technique and the different modalities available. The interpretation of bowel ultrasound findings will include: the assessment of bowel wall thickness, layer conservation, thickening symmetry, extent and distribution, and vascularization with the color Doppler ultrasound and with intravenous contrast. It will also include the assessment of caliber, elasticity, and bowel motility, the evaluation of other additional findings on the wall, and transmural, lymph node, and mesenterium alterations.

Preparation, technique, and study modalitiesPreparationThe patient does not require specific preparation for an ordinary bowel ultrasound. They are only asked to fast for at least 4−6 hours1 for the purpose of reducing luminal air, since excessive amounts of the latter hamper exploration, and in order to reduce peristalsis.

Exploration techniqueAlthough each exploration should be guided by the clinical context, an optimal assessment of the gastrointestinal tract requires a systematic exploration, knowledge of the anatomical references, and combining the use of different frequency transducers. Moreover, gradual compression is advisable in order to reduce the distance between the transducer and the target area and also to improve the acoustic window, which is obtained by the movement of the intra-abdominal fat and the intestinal segments interposed with gas.2

First of all, the solid abdominal organs should be evaluated with a low-frequency convex transducer, followed by an initial study of the small bowel and the colon to ascertain anatomical arrangement and to attempt to detect pathological findings. Similarly, thanks to its greater degree of penetration, it tends to be preferable in obese patients in the study of pelvic bowel loops and the rectum. The bowel is then explored with a medium- or high-frequency convex or lineal transducer (5−15 MHz), whose superior resolution makes it possible to perform a meticulous assessment of the suspect intestinal segments, and define bowel wall layer status and alterations in the adjacent structures (perienteric fat, peritoneum, adenopathies, and vessels).3,4 A convenient point of departure is the cecum, normally located in the right iliac fossa and recognizable due to its fecal matter content with acoustic shadow and lack of peristalsis. The transducer is then moved following the different portions of the colon continuously until at least as far as the proximal sigmoid. Bladder filling often allows us to ascertain that the rectum is normal. Moreover, from the cecum it is easy to locate the terminal ileum, which should be followed proximally, and the rest of the ileum and the jejunum then evaluated with parallel transducer movements in the craniocaudal direction until the entire abdomen and pelvis have been covered; finally, the gastric antrum and the duodenum can be explored as far as the epigastrium.1–3,5,6

Doppler techniquesColor Doppler and power Doppler images are useful for detecting the presence or absence of vascularization in lesions, as well as flow increases in both the mesenteric vessels that lead to the intestinal loop and the intramural vessels of the pathological bowel segment.

It is important to adjust color sensitivity to assess mural vascularization, using a special pre-optimized presetting to detect slow small-vessel flow. Color persistence should be between medium and high, with a low wall filter (40−50 Hz), PRF between 800 and 1500, and low speed scales. Gain should be adjusted to the maximum, albeit avoiding color noise artifacts.7 The absence of vascularization in a segment with thickened wall may be due, in some cases, to the device's scant sensitivity, an inadequate choice of Doppler parameters, high body mass index, or deep loop location.

Oral contrastJust like MR enterography or CT enterography, in ultrasound, the intake of a non-absorbable anechoic liquid contrast (e.g. 500 ml of polyethylene glycol solution) produces complete distension of the small intestine8 and reduces acoustic gas artifacts, translating into greater precision for wall assessment.9 Its acronym is SICUS (small intestine contrast ultrasonography). The studies that use this technique present a greater capacity to assess the proximal small intestine and to detect stenosis, as well as to reduce inter-observer variability. However, the duration of the procedure is also longer, increasing from 25−60 min, and the increased peristalsis makes the color Doppler more difficult to assess.10,11

Intravenous contrastThe only second-generation intravenous contrast approved by the European Medicines Agency for use in abdominal ultrasound is SonoVue®, which contains sulfur hexafluoride microbubbles.

The frequency of the transducer selected determines the contrast dose, which ranges between 2.4 and 4.8 mL.1 Unlike the Doppler image, it makes it possible to study the microvascularization of the bowel wall, whose normal enhancement pattern comprises three phases: a) 10–20 seconds: arrival of the contrast at the blood capillaries; b) 30–40 seconds (arterial phase): maximum intensity is reached; c) 30–120 seconds (venous phase): contrast wash-out.12,13 With a view to reducing subjectivity in the qualitative analysis of the enhancement, modern ultrasonographs include different computing tools for quantitative and semi-quantitative analysis.14 There is a known linear relationship between the concentration of microbubbles and the intensity of the ultrasound signal, rendering it possible to quantify the enhancement of the contrast to ensure that the method is more objective.15 This technique is also indicated for discriminating between the vascular or avascular nature of inflammatory masses and distinguishing between phlegmons (with enhancement) and abscesses (no enhancement).1,16

ElastographyDepending on the system used to estimate tissue stiffness, there are two types of elastography: "strain'' and "shear wave''. Most of the studies in the gastrointestinal tract have been performed in patients with Crohn's disease to assess its capacity to classify stenoses as inflammatory or fibrous in patients with this condition17,18 in which the "strain" technique is preferably recommended.19 Elastography also provides valuable information for the preoperative staging of rectal cancer when used together with the endorectal ultrasound.19 Both of these indications are reflected in the recent EFSUMB (European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology) recommendations on the use of elastography in the digestive tract.19

Normal and pathological patternsThe evaluation of the intestinal tract should be performed taking into account the ecographic characteristics of the wall, intraluminal content, peristalsis, and extraintestinal findings. The section will be explored depending on fold location and pattern. The stomach presents more or less thick folds, depending on luminal content, whereas the small intestine loops may present highly variable appearances depending on distension, air or liquid content; the jejunum presents the characteristic valvulae conniventes, its folds being more stacked and containing more fluid, unlike the ileum, whose walls are smoother and present less peristalsis. The colon virtually always presents greater gas content and a pattern of haustra, and its location can be used as a reference point in the paracolic recesses.1,3,5,20

Bowel wallCharacteristicsThe bowel wall's normal thickness is less than 2 mm when the lumen is distended,1 although if it is collapsed then up to 3 mm in the small intestine and 4 mm in the colon may be normal.21 The exceptions are the stomach, which can measure up to 6 mm, the pyloric antrum, and the rectum (up to 7 mm). In the absence of disease, the sigmoid may present muscular hypertrophy and be up to 5 mm thick.2,5,21,22

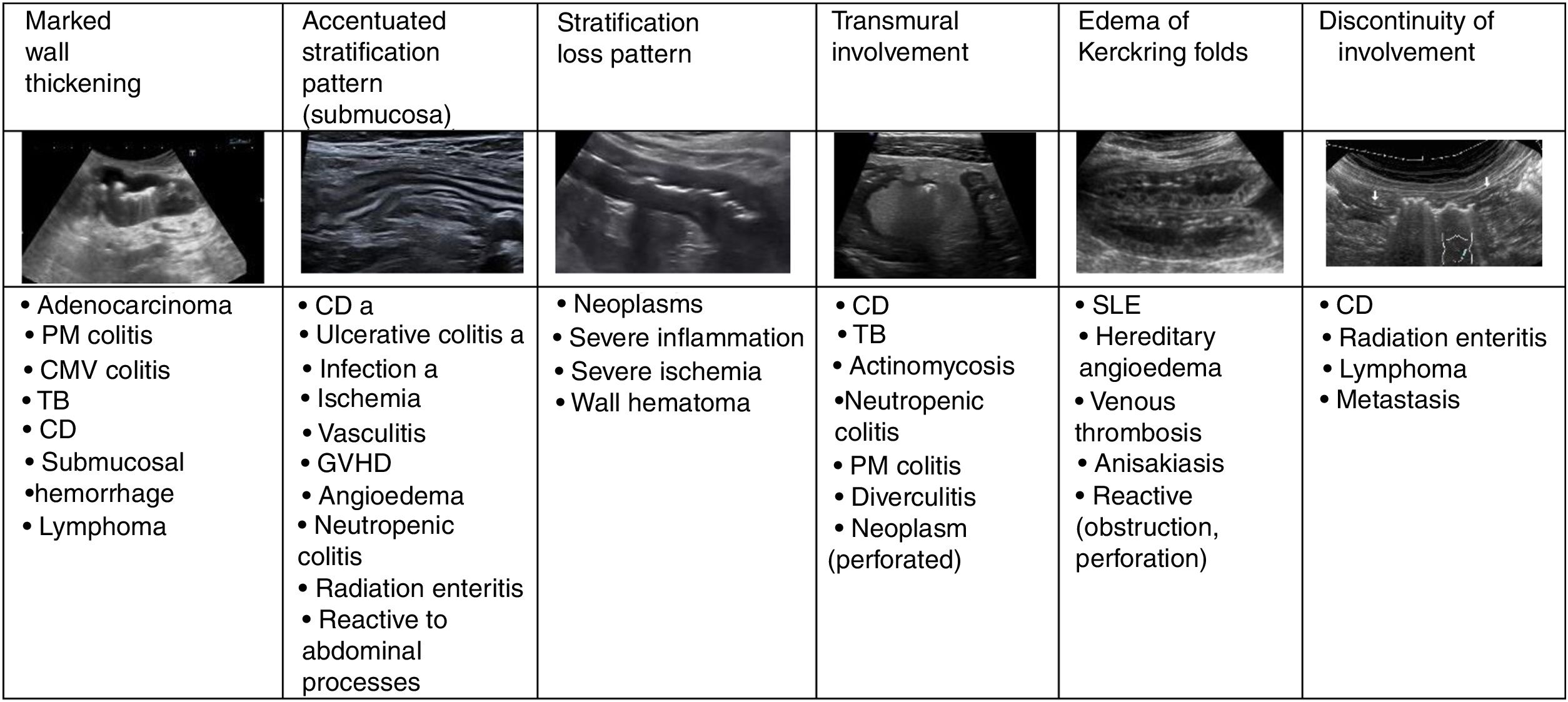

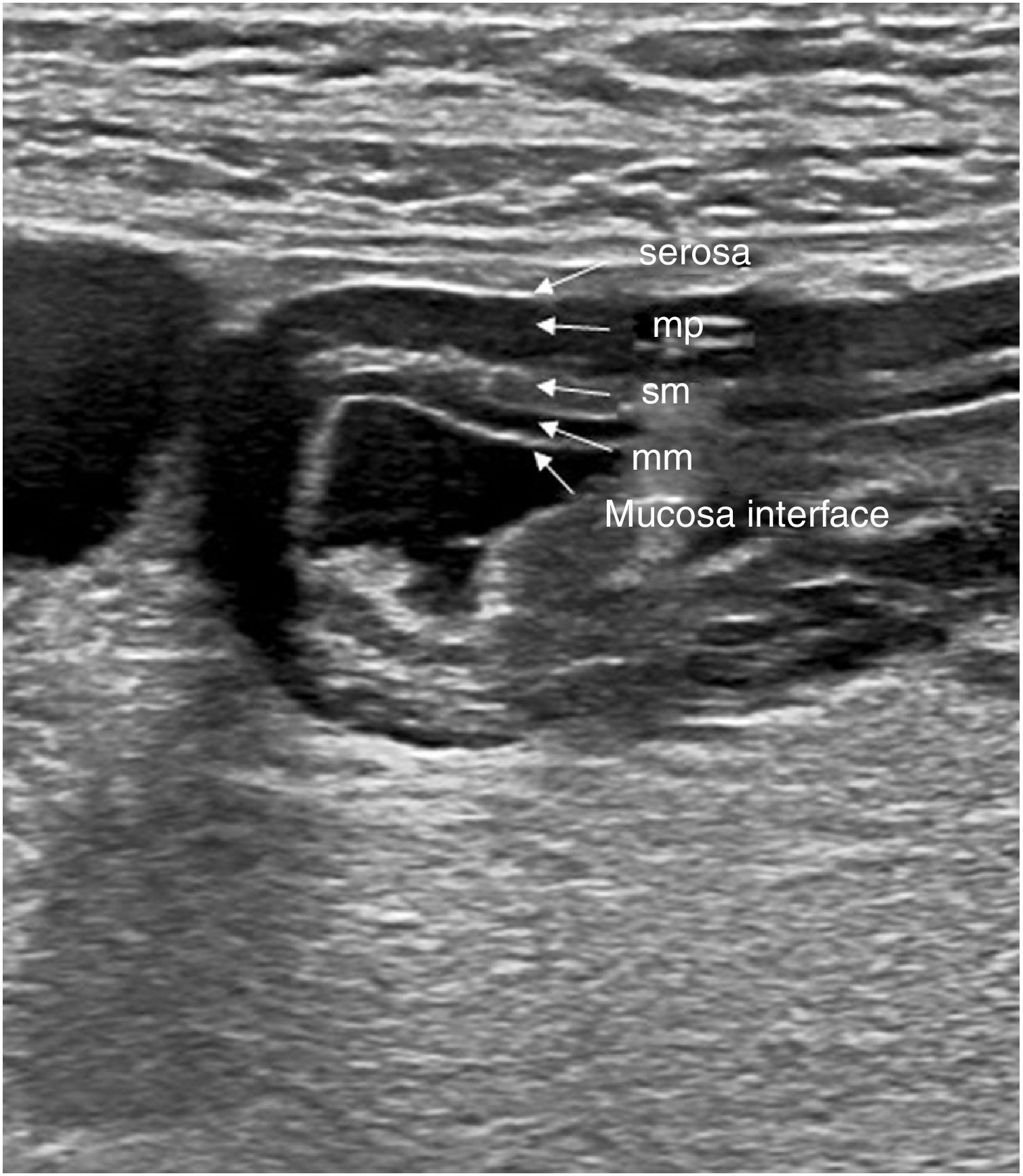

Classically, 5 layers are defined in the bowel wall, with echogenicity alternating between them23 (Fig. 1). These layers can be identified better if the wall is thickened, with fluid in the lumen, and using high-frequency transducers.

Wall thickeningIncreased wall thickness is the main finding in the bowel pathology study and is also the only quantitative parameter. Only this value is used as disease criteria in most published studies. The measurement should be taken from the serosa to the interface of the mucosa and the lumen, and although it is a simple sign to assess, it is unspecific because it presents in most inflammatory, infectious, ischaemic, and tumorous conditions.2,5 The thickening may be highly prominent in tumorous conditions, although it can also be very pronounced in certain inflammatory or infectious processes (Fig. 2)24.

Normal ultrasound appearance of the gastric antrum wall layers. Axial image showing 5 layers which, from the inside to the outside, are: 1) mucosa interface, echogenic layer that represents the interface between the gastric lumen and the mucosa surface; 2) muscularis mucosae (mm), hypoechoic layer that represents the deep mucosal layer; 3) submucosa (sm), hypoechoic layer 4) muscularis propria (mp), hypoechoic layer 5) serosa, echogenic and outermost layer.

Asymmetrical thickening is characteristic of neoplasms, although it may also occur in Crohn's disease, tuberculosis, and intestinal actinomycosis, in enteropathy caused by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diverticulitis, and lymphoma (exceptionally, it is symmetrical in this type of neoplasm and in scirrhous carcinoma).3,24 Symmetric wall thickening also takes place in gastric or duodenal ulcers,20 and in these cases it is useful to search for periduodenal fluid and the presence of gas in the ulcer in the thickened wall.

Wall stratificationThe accentuated stratification pattern is described when the layers are clearly recognizable, particularly the submucosa (echogenic). In general, it is characteristic of benign conditions and is more pronounced in inflammatory infections and conditions, including Crohn's disease (Fig. 2).4,25 Moreover, the loss of stratification is one of the characteristics of malignant digestive tract processes. Nevertheless, and even if there is no tumor infiltration, the existence of substantial leukocyte infiltrate or another type of exudate may generate hypoechogenicity of the submucosal layer and an appearance of layer loss, as occurs in cases of inflammation or severe ischaemia (Fig. 2).26–28

In diseases with transmural involvement, layer appearance is also lost and the bowel wall presents a very low echogenicity, which may be accompanied by other extramural findings such as fistulae, phlegmons, and abscesses,4 and sometimes even perforation with ectopic gas in the adjacent area. Although this is more frequent in Crohn's disease, other conditions, such as diverticulitis, may present this way (Fig. 2).

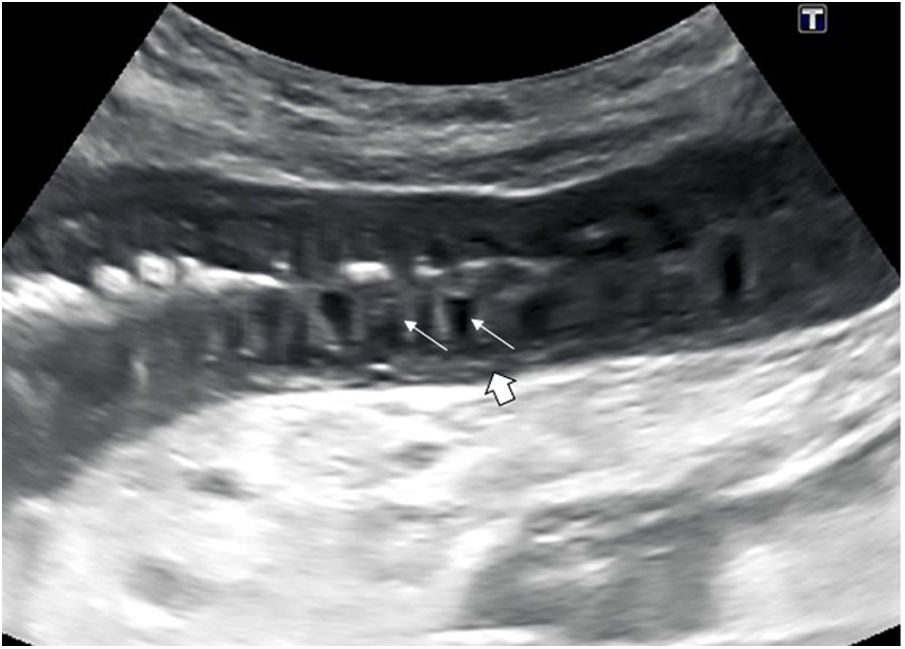

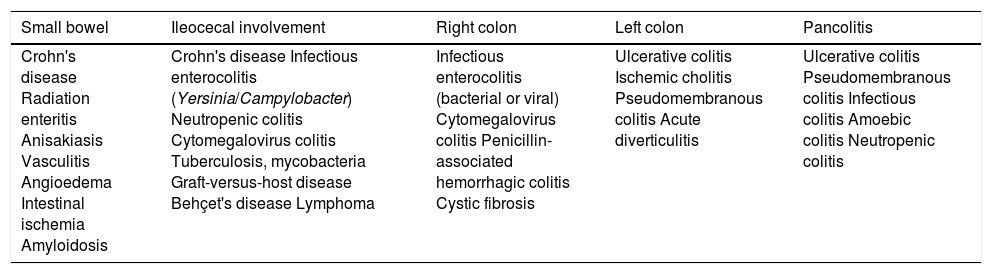

One characteristic pattern is edema of the muscularis-mucosae, in which the most superficial layer takes on a cystic appearance in the valvulae conniventes or edema of the Kerckring folds (Fig. 3). This finding has been described in a series of conditions, normally acute, reversible, and benign (Table 1).29–31 In view of the variety of etiologies, they must be interpreted in the clinical and evolutional context.

Bowel disease distribution.

| Small bowel | Ileocecal involvement | Right colon | Left colon | Pancolitis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crohn's disease Radiation enteritis Anisakiasis Vasculitis Angioedema Intestinal ischemia Amyloidosis | Crohn's disease Infectious enterocolitis (Yersinia/Campylobacter) Neutropenic colitis Cytomegalovirus colitis Tuberculosis, mycobacteria Graft-versus-host disease Behçet's disease Lymphoma | Infectious enterocolitis (bacterial or viral) Cytomegalovirus colitis Penicillin-associated hemorrhagic colitis Cystic fibrosis | Ulcerative colitis Ischemic cholitis Pseudomembranous colitis Acute diverticulitis | Ulcerative colitis Pseudomembranous colitis Infectious colitis Amoebic colitis Neutropenic colitis |

An increase in the mucosa-muscularis mucosae is also observed in nodular lymphoid hyperplasia, with a pronounced nodular and hypoechoic thickening of this layer, affording it a stony-like appearance, with the submucosa appearing thin. This entity tends to present in children and young people in the colon, terminal ileum, and appendix and may be an incidental finding, although it has been related to infectious diseases and to immunodeficiency conditions.32 It tends to be associated with regional adenopathies.33

There is a characteristic type of colitis, called pseudomembranous colitis, caused by Clostridium difficile, which may initially present as a very pronounced and nodular hypoechoic thickening of the mucosa, correlated to the accordion-like appearance described in the CT (very prominent haustration).34,35

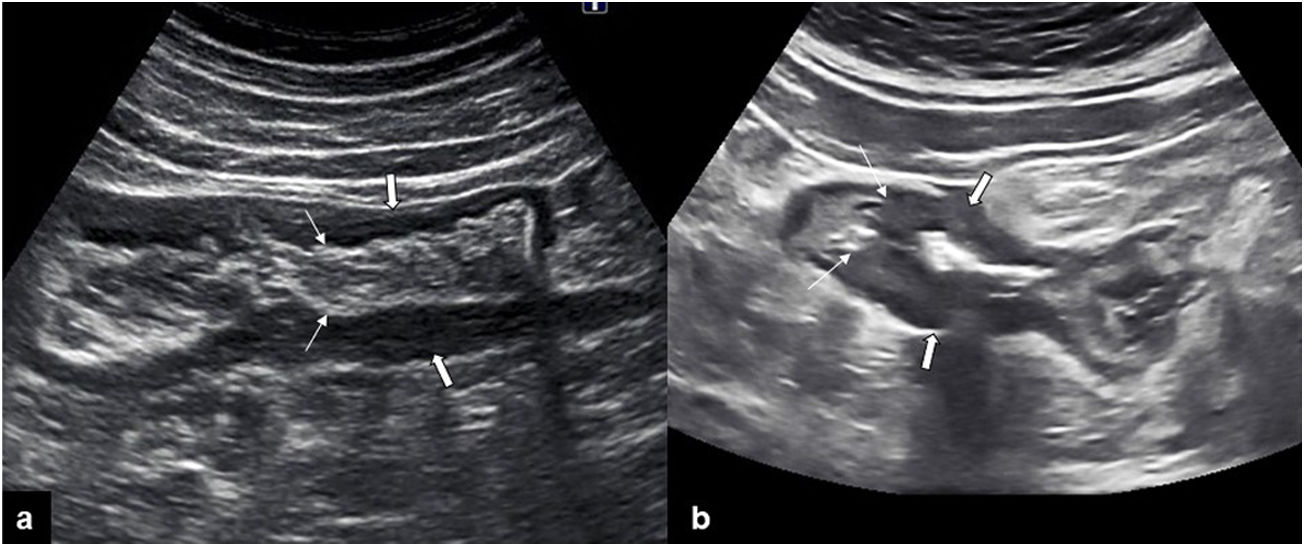

The thickening of the muscularis propria layer is clearly observed in diverticular conditions of the colon, be it in diverticular disease (muscular hypertrophy) or acute chronic inflammation (diverticulitis). It is identified as a marked prominence of the hypoechoic layer of the muscualris, not always symmetrical, with the characteristic diverticula protruding outside the wall. The inner layers, such as the muscularis mucosae or submucosa, are preserved, which is a very useful finding for distinguishing between this condition and tumor-induced wall thickening, particularly in perforated neoplasms36 (Fig. 4).

a) longitudinal image of the sigmoid, presenting wall thickening at the expense of the hypoechoic muscularis propria layer (thick arrows), with inner layers preserved (thin narrows), suggesting benignness. b) Longitudinal image of the sigmoid, showing marked wall thickening, loss of pattern in layers (thick arrows), and an abrupt transition (thin arrows), findings which suggest malignancy.

Other entities may affect the outermost wall layers (serosa), such as tumor implants or intestinal endometriosis, and generally present as iso -or hypoechoic lesions, which mold the wall and may cause loop retractions and kinks.22,37 To recognize these entities, it is very important to observe that the innermost layers are preserved, although if they progress they may infiltrate the entire wall. In the specific case of bowel endometriosis, the location may be the rectum, sigmoid, or even the ileum, with very hyperechoic lesions, with a lenticular, rounded, or feather crest-like appearance which retract the loop and can even cause obstruction.38 The characteristic ultrasound image, together with the clinical context, will assist in the diagnosis (Fig. 5).

ExtensionLong involvement (10−30 cm) is characteristic of Crohn's disease, infectious pathology, radiation enteritis, edema, and ischemic, vascular, or hemorrhagic origin, as well as lymphoma. The involvement of short segments is typical of adenocarcinoma, unlike diverticulitis, in which extension is moderate (5−10 cm). Discontinuous involvement is characteristic of Crohn's disease although it may also exist in other entities28 (Fig. 2).

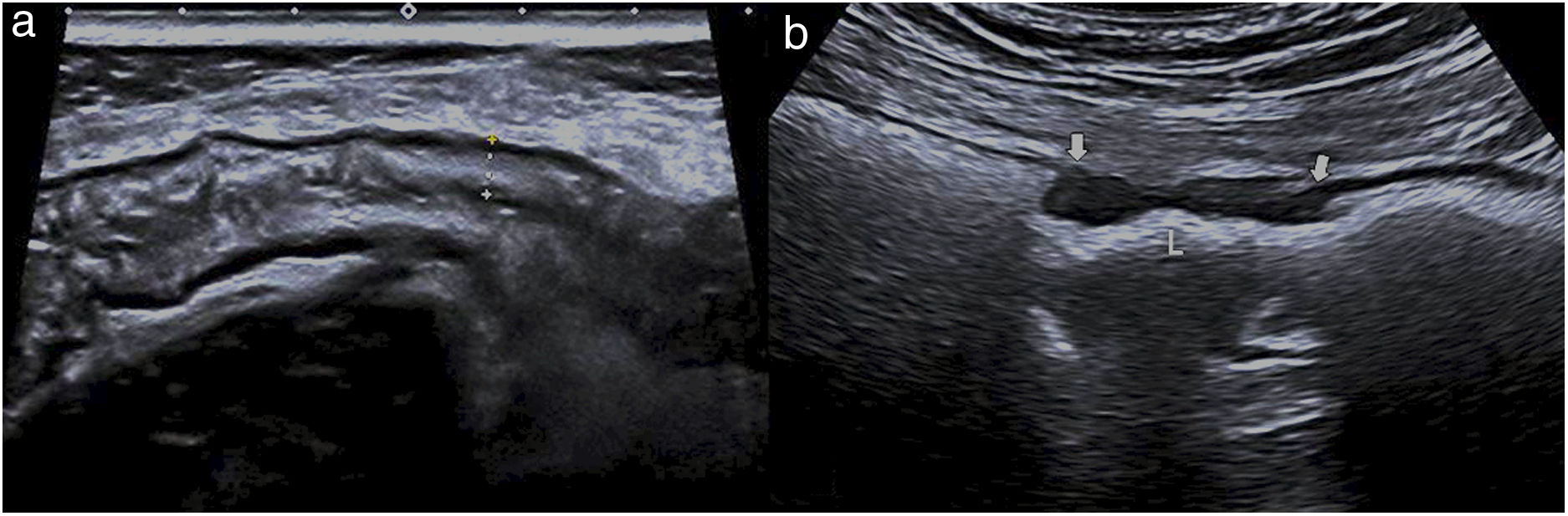

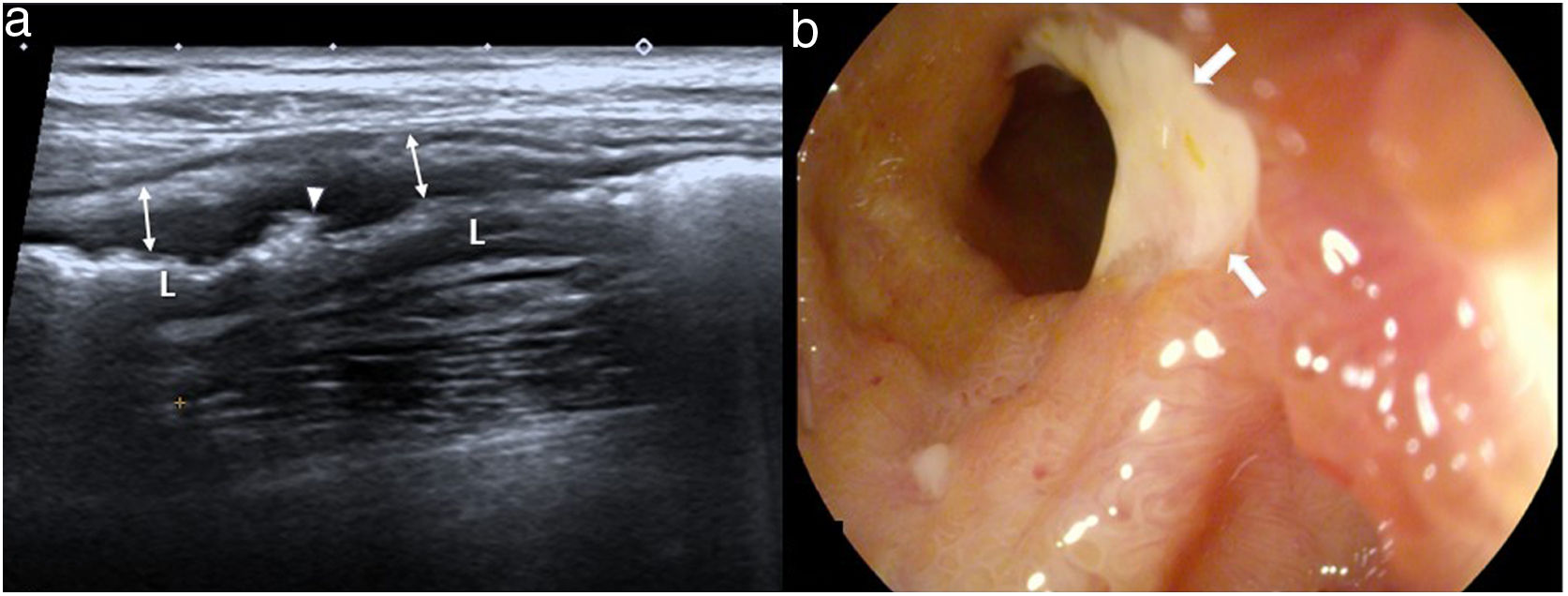

As a rule, long, concentric involvement with preserved layers are benign characteristics, whereas a short, isometric section with layer-structure loss is suggestive of malignancy (Fig. 6).36

a) Ultrasound image of the descending colon presenting symmetric wall thickening, with the layers preserved (between cursors) and involvement of a large section, related to ischemic colitis. b) Ultrasound image showing a short section of the sigmoid wall with symmetric and hypoechoic thickening (thick arrows) caused by adenocarcinoma, with loss of layer structure. L: lumen.

The distribution of the affected segments may also provide information about the underlying pathology, since certain conditions have an affinity for certain sections of the digestive tract33 (Table 1).

VascularizationIn general, there will hardly be any signal on a color Doppler ultrasound of a normal digestive tract wall. The presence of hyperemia points towards an inflammatory and neoplastic condition. A semi-quantitative scale is used to measure the degree of vascularization, rating the number of vessels detected per square centimeter. The modified Limberg score comprises 4 grades: grade 0 = absence of vessels; grade 1 or mild flow = less than 2 signals/cm2; grade 2 or moderate flow = from 3 to 5 signals/cm2; grade 3 or marked flow = more than 5 signals/cm2.39 This scale is used particularly in inflammatory bowel disease to measure inflammatory activity.

The absence of flow may point to an ischemic origin, as in the case of acute mesenteric ischemia,40,41 where mesenteric vessel permeability can be checked. The use of intravenous contrast makes it possible to assess ischemic loop perfusion.42

Caliber, elasticity, and peristalsisMaximum intestinal loop diameter varies from 2 to 2.5 cm, and that of the colon up to 5 cm, although the cecum may exceed this measurement. If the lumen is collapsed, a central echogenic line will be visible, representing the interface between the two mucosas. However, if there is fluid in the lumen, the content is anechoic and the walls can be defined better, and if there is obstruction, the vavulae conniventes of the small bowel and the haustra of the colon will be marked.20,22,28 The ultrasound cannot only detect the presence of bowel obstruction but can also locate extent and cause.

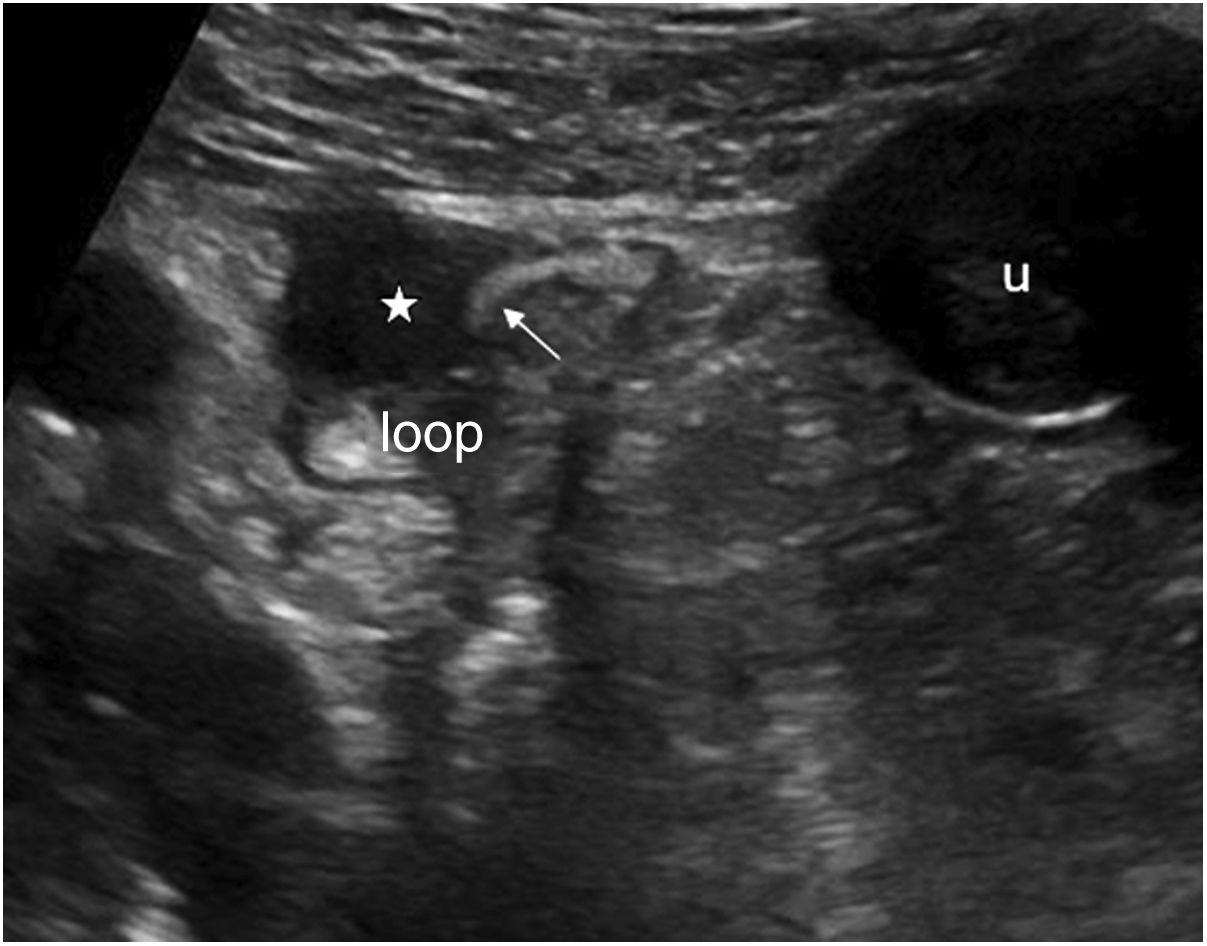

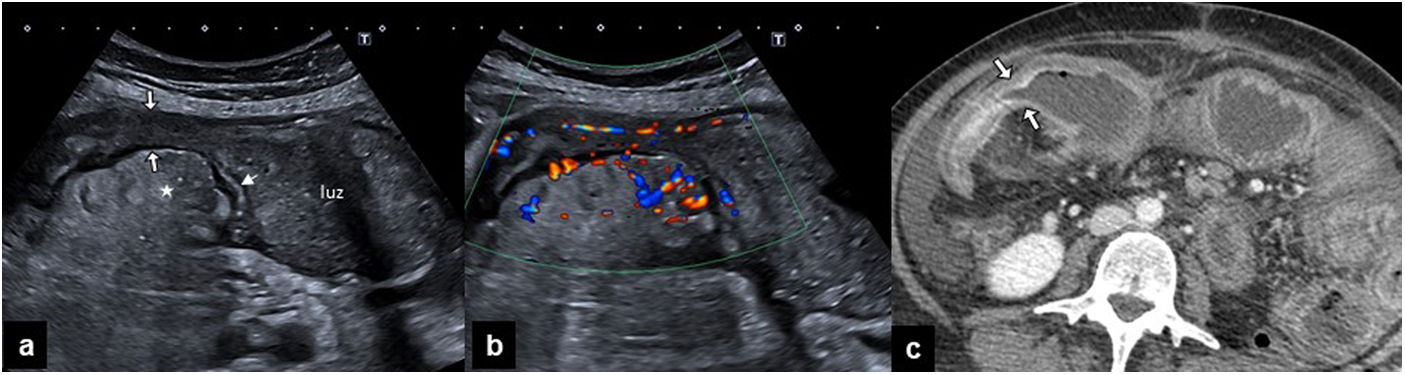

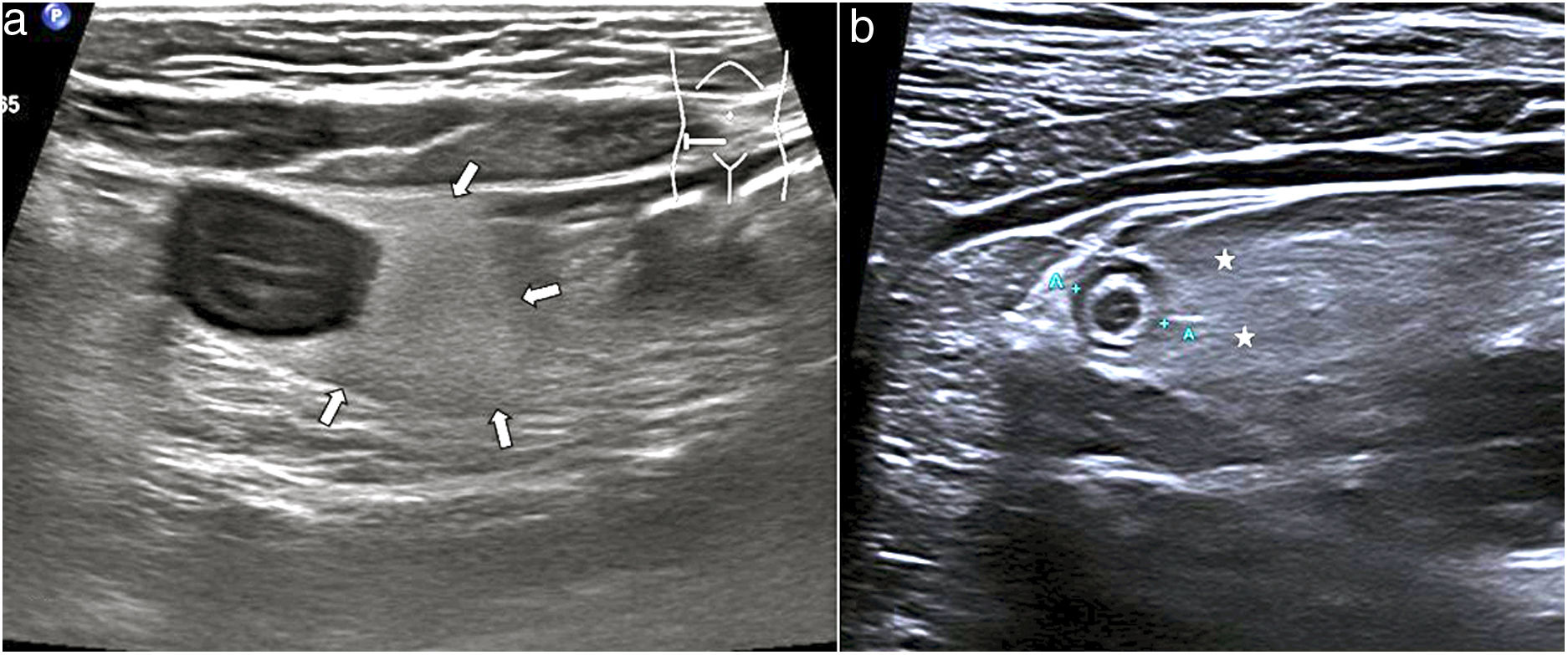

When the bowel wall is pathological, it loses elasticity, and this presents as stiffness or difficulty in compression. This is one of the most useful ultrasound findings for recognizing inflammation, as in the case of appendicitis. Moreover, when the wall is thick and stiff, it may cause luminal stenosis, as occurs in Crohn's disease or in bowel tumors (Fig. 7).

a) Ultrasound of the right flank of a patient with Crohn's disease showing a dilated small loop with intestinal content in the lumen. Distally, there is homogeneous thickening of the wall (thin arrow), which conditions stenosis (thick arrows), causes obstruction, and associates inflammation of the fat surrounding the mesenteric portion of the loop (asterisk). b) The color Doppler ultrasound of the same segment shows marked hyperemia of the stenotic loop wall and of the mesenteric vessels. c) Computed tomography of the abdomen with intravenous contrast, showing loop dilation (a) and stratified enhancement of the wall of the inflammatory stenosis (arrows).

One of the most interesting properties of the ultrasound technique is its capacity to assess intestinal dynamics.1 The estimation and quantification of peristaltic activity is difficult and subjective since it will depend on fasting status and other more complex factors. Increased peristalsis presents with to-and-fro fluid and wall movements. The frequency and amplitude of contractions is highly pronounced in infectious conditions and in malabsorption enteropathies. In cases of acute obstruction, peristalsis is increased as the contents attempt to overcome the obstacle, but if the obstruction is severe or long-evolving, the opposite effect may occur and it may present as paralytic ileus with scant bowel loop movement. The presence of free fluid has been correlated with a high degree of obstruction.43

In coeliac disease, motility disorder is accompanied by other alterations, such as loss of the Kerckring folds in the jejunum, jejunisation of the ileum, excess luminal fluid, transient invaginations, and an increase in the number and size of the adenopathies in the active disease.19

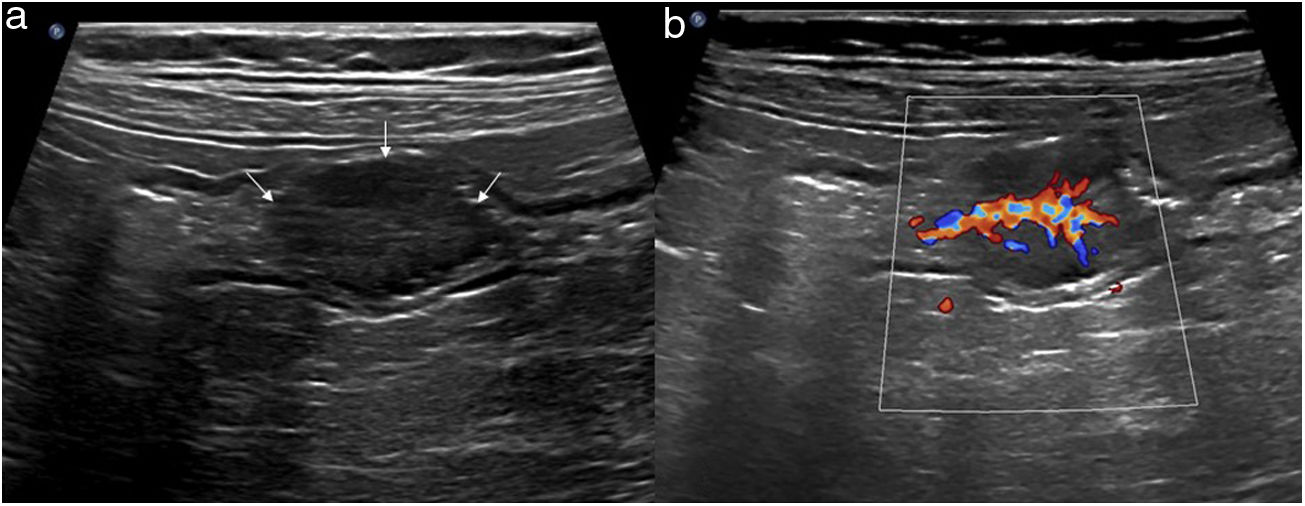

MesenteriumThe involvement of fat in certain acute inflammatory processes such as diverticulitis and appendicitis is very characteristic and can be recognised through increased echogenicity and the absence of compression. This finding makes it possible to locate the affected bowel segment, since besides surrounding it, it is sometimes more prominent than the wall thickening (Fig. 8). Other conditions with fat involvement are foreign body perforations, duodenal ulcers, epiploic appendagitis, and omental infarction; the latter two entities have no associated bowel wall thickening.2

a) Ultrasound of a patient with Crohn's disease with inflammatory activity. Symmetric and hypoechoic thickening of the terminal ileum. Adjacent to it is the mesenteric fat with augmented echogenicity (arrows), with loss of its striated appearance and forming a compact tissue, causing separation of the other loops. b) Patient with acute appendicitis, showing the fat with augmented echogenicity (asterisk), enhancing and isolating the second appendix (between cursors).

One particular form of mesenteric involvement occurs in Crohn's disease, described as fibrofatty proliferation. This finding presents as marked hyperechoic tissue with mass effect surrounding the inflamed loop and displacing the other loops. Although it has been related to inflammatory activity, it can be found in remitting diseases. It may be associated with increased vascularization with color Doppler ultrasound (comb sign) and it diminishes or disappears in some patients with a good response to treatment.25

AdenopathiesMesenteric lymph nodes are part of the evaluation of bowel condition and are a very frequent and unspecific finding. The size, number, form and echogenicity of adenopathies in the abdominal cavity can help distinguish between infectious, inflammatory, or tumor-related causes.

Normal mesenteric lymph nodes have a short-axis size of less than 4 mm in adults and up to 8 mm in children and are oval-shaped.1 Infectious or inflammatory adenopathies are small, rounded, and multiple and are located at the root of the mesenterium or the perienteric vasculature. Bacterial enterocolitis has been described frequently related to Campylobacter, Salmonella, and Yersinia, with different degrees of involvement of the ileocecal region.2

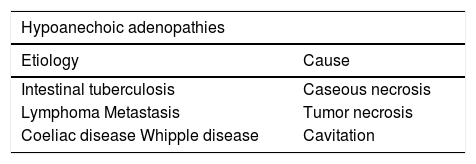

In tuberculosis, adenopathies may be markedly hyperechoic on account of necrosis (Table 2). This entity, besides hyperechoic wall thickening, usually involves mesenteric alterations. Other entities that are described in the table may present this anechoic appearance of the adenopathies. In coeliac disease, this appearance is associated with a poor prognosis or malignancy (T-cell lymphoma).

The presence of adenopathies with calcifications is related to metastasis of ovarian tumors and of carcinoid tumor, treated lymphoma, amyloidosis, and tuberculosis.22

Additional wall and extraluminal findingsSuperficial and deep ulcers, fissuresSuperficial and deep ulcers can be identified on the ultrasound when the bowel wall is engrossed, as in Crohn's disease, and take the form of small echogenic linear images on the surface layers or coarser irregularities in wall thickness when the ulcers are deeper (Fig. 9). If they go deeper, they cause fissures which, once they extend outside the wall, cause sinus tracts that can be identified as linear hypoechoic pathways that cross the mesenterium, ending in a blind-sac fundus or a mesenteric inflammatory mass.25

Crohn's disease of the ileum. a) Longitudinal image showing marked wall thickening (arrows), preservation of the pattern in layers and multiple irregularities in the most superficial layer, one of them more pronounced (arrow head), which corresponds to a gas-filled ulcer. b) Ileoscopy image showing a large ulcer (arrows) in the terminal ileum, with hyperemic mucosa.

Fistulas are identified as hypoechoic tracts that connect one bowel loop to another, or else to other organs, retroperitoneum, or skin. They may contain gas; in this case, the tract will be hyperechoic. In Crohn's disease, they are often associated with stenosis with inflammatory activity.

Both phlegmons and abscesses are inflammatory masses that present a similar appearance on the ultrasound. Generally speaking, they are hypoechoic lesions which, in the case of phlegmons, are more poorly defined, whereas abscesses present more precise walls and may contain gas or a hydroaerial level. Colour Doppler, and above all the use of intravenous contrast, will provide a definite differentiation: phlegmons present vascularization on the inside and diffuse enhancement, whereas abscesses only enhance in the peripheral area, with a central area that does not pick up contrast and the absence of color Doppler flow. Contrast provides a better definition of abscess size, which helps in treatment decisions.4,5,16

DiverticulaDiverticula appear on the ultrasound as sacculations protruding outside the bowel wall, their appearance depending on their content: they will be hypoechoic if they are full of fluid, hyper-echogenic if they contain gas, or have posterior acoustic shadowing if they contain fecal matter. Although they can be found throughout the bowel, they are more common in the left hemicolon.

The typical findings of acute diverticulitis are: a) segmental bowel wall thickening with preserved layer structure, with predominance of the muscularis propria layer; b) increased echogenicity of the adjacent fat, and c) inflammation of the diverticula.44 In addition, small gas bubbles may be found in the adjacent areas in complicated diverticulitis, as well as fistulas and abscesses, as signs of micro-perforation.45

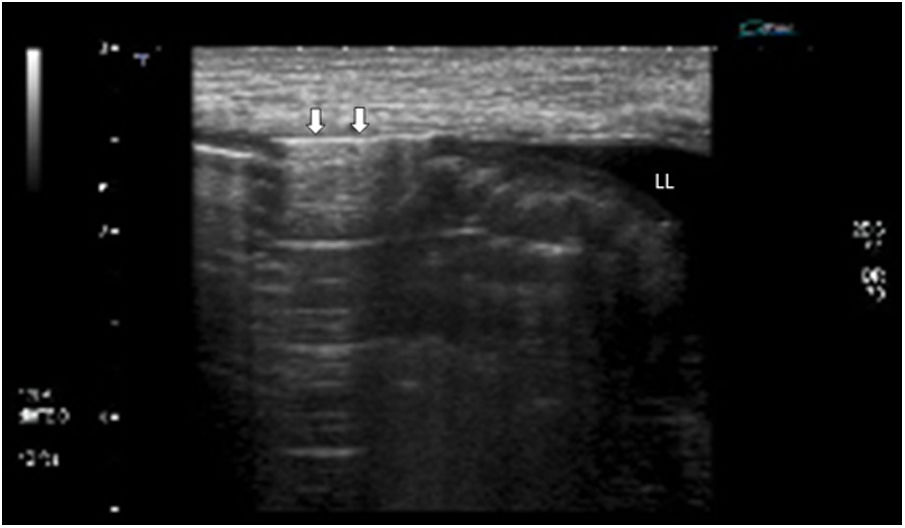

Extraluminal gasSome of the most common causes of pneumoperitoneum due to perforated hollow viscus are duodenal and gastric ulcers, diverticulitis, Crohn's disease, perforated neoplasms, yatrogenic pathology, and trauma. Free-gas is best studied with the patient in the supine or left lateral recumbent position with an intercostal approach. It is identified as a hyperechoic line or small gas bubbles which cause reverberation artifacts and are located between the abdominal wall and the anterior hepatic surface. This gas is moved by changing the patient's position and disappears when pressure is applied (Fig. 10).

a) longitudinal image on the left flank, with linear transducer, in a patient with intestinal perforation. There is a linear hyperechogenic image (arrows) interposed between the anterior abdominal wall and the adjacent bowel loops, corresponding to ectopic gas in the peritoneal cavity. Small amount of free fluid (FF).

The gas can also be recognised inside intra-abdominal collections as small hyperechogenic dots, or as a linear image if it is more abundant. In the event of these findings, in a suitable context, the presence of bowel loops with fluid in the lumen and walls can indicate generalised peritonitis.21,46,47

Pneumatosis intestinalisAlthough pneumatosis or the presence of gas in the bowel has been described in association with two pathologies that have a poor prognosis, namely intestinal ischemia and necrotising enterocolitis, it can also be found in other benign conditions. Pneumatosis can be detected as small linear echogenic foci in the thickness of the engrossed wall, following the folds or surrounding the entire wall (circle sign), which differentiates it from intraluminal gas and pseudo-pneumatosis, in which the air is trapped between the bowel folds.28,48

Wall masses and tumorsIn ultrasonography, small tumors are difficult to identify. They may be classified as: a) intraluminal or polyploid lesions; b) intramural, causing wall thickening; c) extraluminal or tumors with exophytic growth.

Intraluminal lesions: they may present as polypoid lesions that extend towards the lumen and are difficult to recognize if the lumen is not distended by fluid or gas. This appearance is presented by the lipomas, which are hyperechogenic and have a soft consistency,37 polyploid adenocarcinomas, which can become very large, and inflammatory polyps, which tend to be small. The presence of the vascular pedicle helps to identify them (Fig. 11).35 Sometimes, these lesions cause invagination.

Intramural tumors: this is one of the most recognized forms of presentation of colon and small bowel-infiltrating neoplasms which, generally speaking, present asymmetric, short thickening with loss of layer structure, and sometimes leads to the appearance of pseudokidney. This pattern is characteristic of adenocarcinomas, which can narrow the lumen and cause bowel obstruction, despite being small. Intestinal lymphoma tends to present with marked and very hypoechoic thickening, although the mucosa can be preserved, and unlike adenocarcinoma it does not cause luminal stenosis. Association with pseudocyst-like adenopathies is frequent.28

Exophytic masses: some tumors depend on the outer layers, such as the muscularis propria, and grow outwards. It is a frequent form of presentation of mesenchymal tumors, such as the leiomyomas and particularly the gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST), which are hypoechoic, well-defined, and highly vascularized. As they grow, they may present cystic areas due to necrosis, hemorrhage, or cystic degeneration.6,49

ConclusionBowel ultrasound offers a unique opportunity to study the digestive tract in a non-invasive way and in physiological conditions, also furnishing us with information about its motility, elasticity, and vascularization while permitting the diagnosis of very diverse types of bowel disease. However, it is a procedure that requires a learning curve, and for which a knowledge of ultrasound technique is required. Its availability, good tolerance, and high performance are conducive to its use in the monitoring of subacute or chronic bowel processes. Moreover, it is the priority technique in children, young people, and pregnant women.

AuthorsResponsible for study integrity: MJMP.

Study conception: MJMP, EBG, and JAMB.

Study design: MJMP and EBG.

Data acquisition: MJMP, EBG, and JAMB.

Data analysis and interpretation: MUMP and EGB.

Statistical analysis: not necessary.

Literature search: MJMP and JAMB.

Drafting of the manuscript: MJMP, EBG, and JAMB.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: MJMP and JAMB.

Approval of the final version: MJMP.

FundingThis research has received no specific funding from public sector agencies, the commercial sector, or non-profit organizations.

Conflicts of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite thais article as: Martínez Pérez MJ, Blanc García E, Merino Bonilla JA. Ecografía intestinal: técnicas de examen, patrones normales y patológicos. Radiología. 2020;62:517–527.