A calyceal diverticulum consists of a cystic eventration in the renal parenchyma that is lined with transitional cell epithelium with a narrow infundibular connection with the calyces or pelvis of the renal collector system; thus, the term pyelocalyceal diverticulum would be more accurate. Very rare in pediatric patients, calyceal diverticula can be symptomatic and require treatment. Calyceal diverticula are underdiagnosed because they can be mistaken for simple renal cysts on ultrasonography. To determine the approach to their follow-up and management, the diagnosis must be confirmed by excretory-phase computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

This article aims to show the different ways that calyceal diverticula can present in pediatric patients; it emphasizes the ultrasonographic findings that enable the lesion to be suspected and the definitive findings that confirm the diagnosis on CT and MRI. It also discusses the differential diagnosis with other cystic kidney lesions and their treatment.

El divertículo calicial (DC) es una eventración quística intraparenquimatosa tapizada por epitelio celular transitorio con una estrecha conexión infundibular con los cálices o pelvis del sistema colector renal, por lo que el término más exacto es divertículo pielocalicial. Muy raro en la edad pediátrica, puede ser sintomático y requerir tratamiento. Está infradiagnosticado por confundirse con quistes renales simples por ecografía; su diagnóstico se confirma con tomografía computarizada (TC) o resonancia magnética (RM) en fase excretora, para determinar su seguimiento y manejo. Nuestro objetivo es mostrar las diferentes formas de presentación de los DC en la edad pediátrica, haciendo hincapié en los criterios ecográficos que permiten una aproximación diagnóstica y en los hallazgos definitivos en TC y RM. También discutimos el diagnóstico diferencial con otras lesiones quísticas renales y su tratamiento.

Calyceal diverticula (CD) are cystic eventrations of the upper urinary tract found within the renal parenchyma and covered by epithelium of non-secretor transitional cells. They contain urine and are located at the periphery of a calyx and communicate with it through a narrow isthmus or infundibulum.1–4

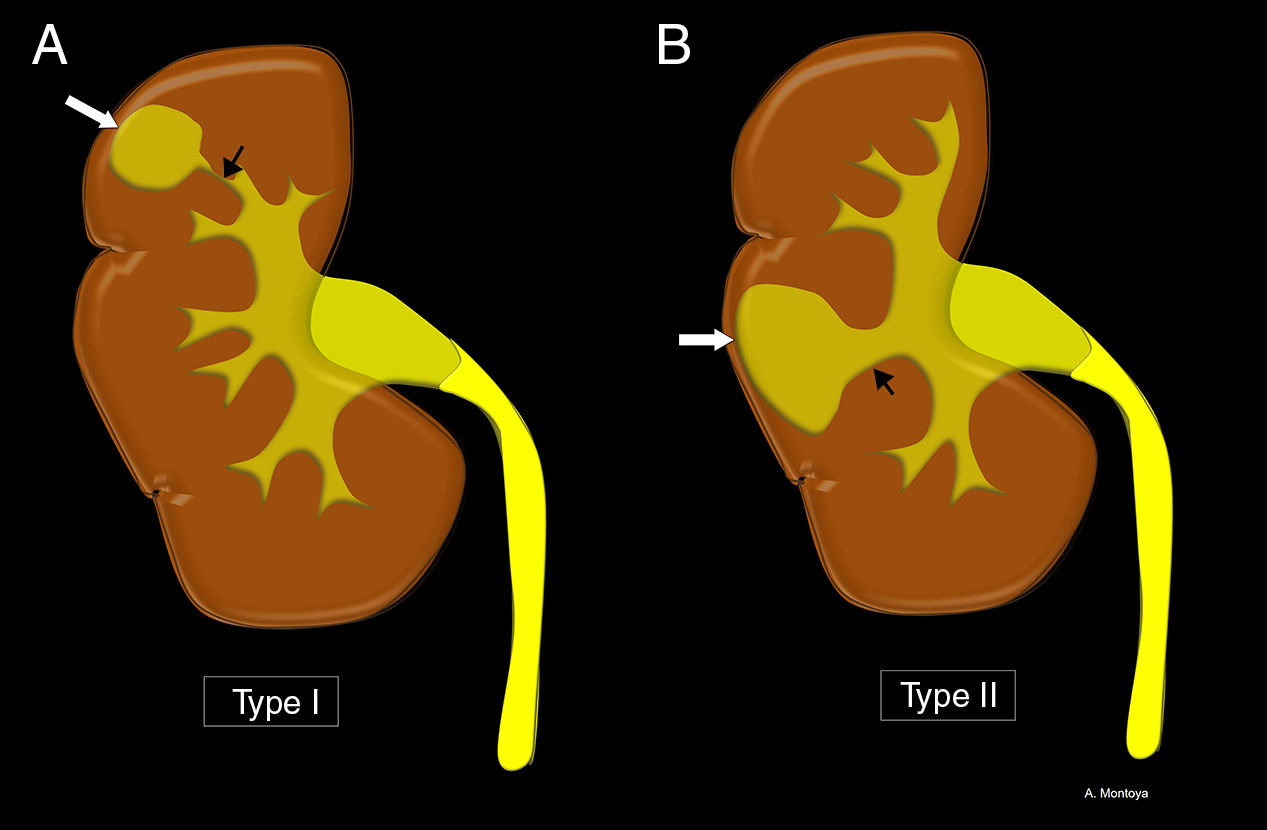

CD are categorized as type I, those that communicate with a minor calyx or infundibulum, or type II, those that stem from the renal pelvis or a major calyx (Fig. 1). Type I is the most common of the two and is usually found in the upper pole. Type II are bigger, usually asymptomatic and located in the interpolar region of the kidney.1,5,6 They can be multiple and bilateral.2

Schematic representation of the different types of calyceal diverticula (CD). (A) Type I. Communication of the CD (white arrow) with a minor calyx through the infundibulum or isthmus (black arrow). (B) Type II. Communication of the CD (white arrow) with a major calyx or pelvis through the infundibulum or isthmus (black arrow).

The exact etiology of CD is unknown, but the hypothesis is that they are congenital. Embryologically, the pyelocalicial system develops from consecutive divisions of the ureteric buds that are surrounded by the metanephric blastema. From the first third to five generations of divisions, the buds dilate to make up the cavity of renal pelvis and the major calyxes. Consecutive subdivisions result in an approximate number of 20 minor calyxes. The reduced number of calyxes occurs due to the absorption of several branches in the pelvis. One of these calyxes can give rise to the formation of a sac connected to the collecting system that dilates under pressure from the urine causing one diverticulum. The similar incidence (3/1000) in children and adults confirms this theory.1,3–6 In adults, acquired CD have been described following infectious processes leading to infundibular fibrosis and stenosis.2,4

Possibly, the true prevalence of CD is higher since they are misdiagnosed after being taken for renal simple cysts. A more precise analysis of the ultrasound findings can help us distinguish CD from renal cysts, being the computed tomography (CT) scan, or the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast in the excretory phase the imaging modalities that confirm the diagnosis.

Our goal will be to show the different clinical presentations of CD during the pediatric age, paying special attention to the ultrasound criteria that allow a certain diagnostic approach and the definitive findings made through CT scan and MRI. We will also be discussing differential diagnosis with other renal cystic lesions and their therapy.

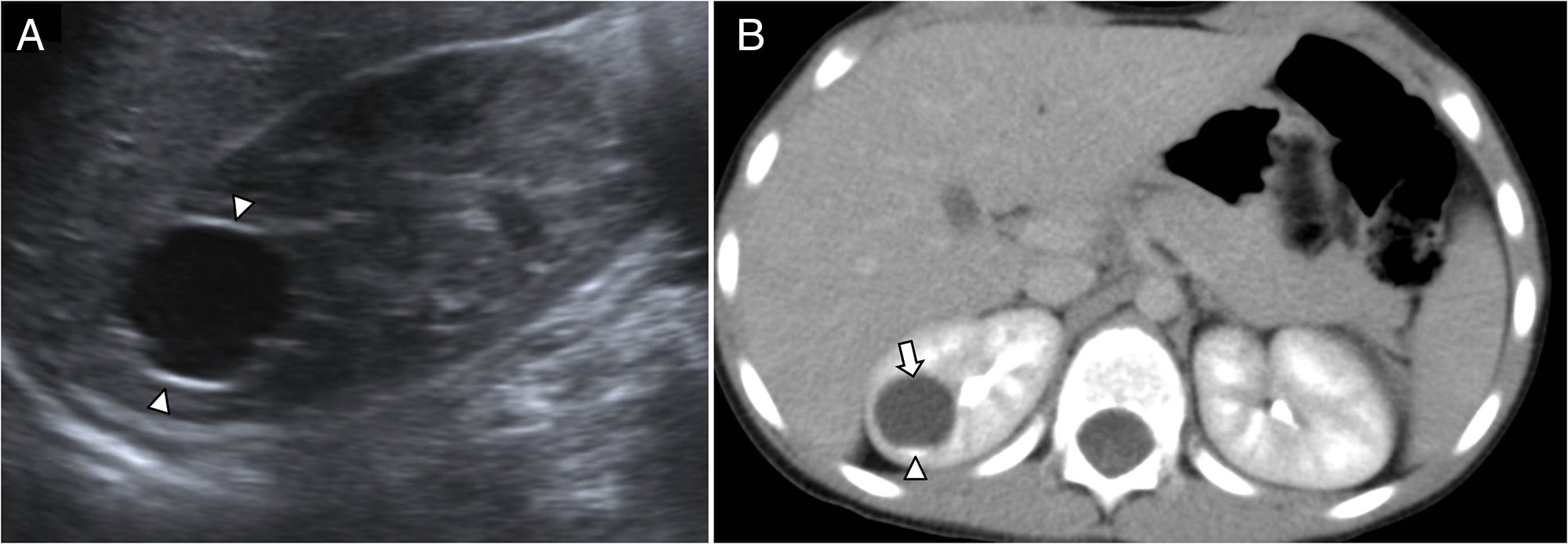

Clinical presentationCD are rare in children and are usually found incidentally in imaging studies conducted for other reasons (Fig. 2). Most remain stable and asymptomatic, but approximately 20% have complications and require therapy.7 Colicky flank pain, hematuria, and recurrent urinary tract infections are some of the most common clinical presentations of symptomatic CD.1,4

Eighteen-month-old baby girl with histiocytosis. Asymptomatic, study conducted according to protocol due to her underlying disease (A) abdominal B mode ultrasonography showing one well-established, polylobulated, anechoic lesion in the upper pole of the right kidney, suggestive of calyceal diverticulum (arrowheads). (B) Abdominal CT scan in the excretory phase at 5min, confirming level of contrast (arrowhead) inside the diverticulum (arrow).

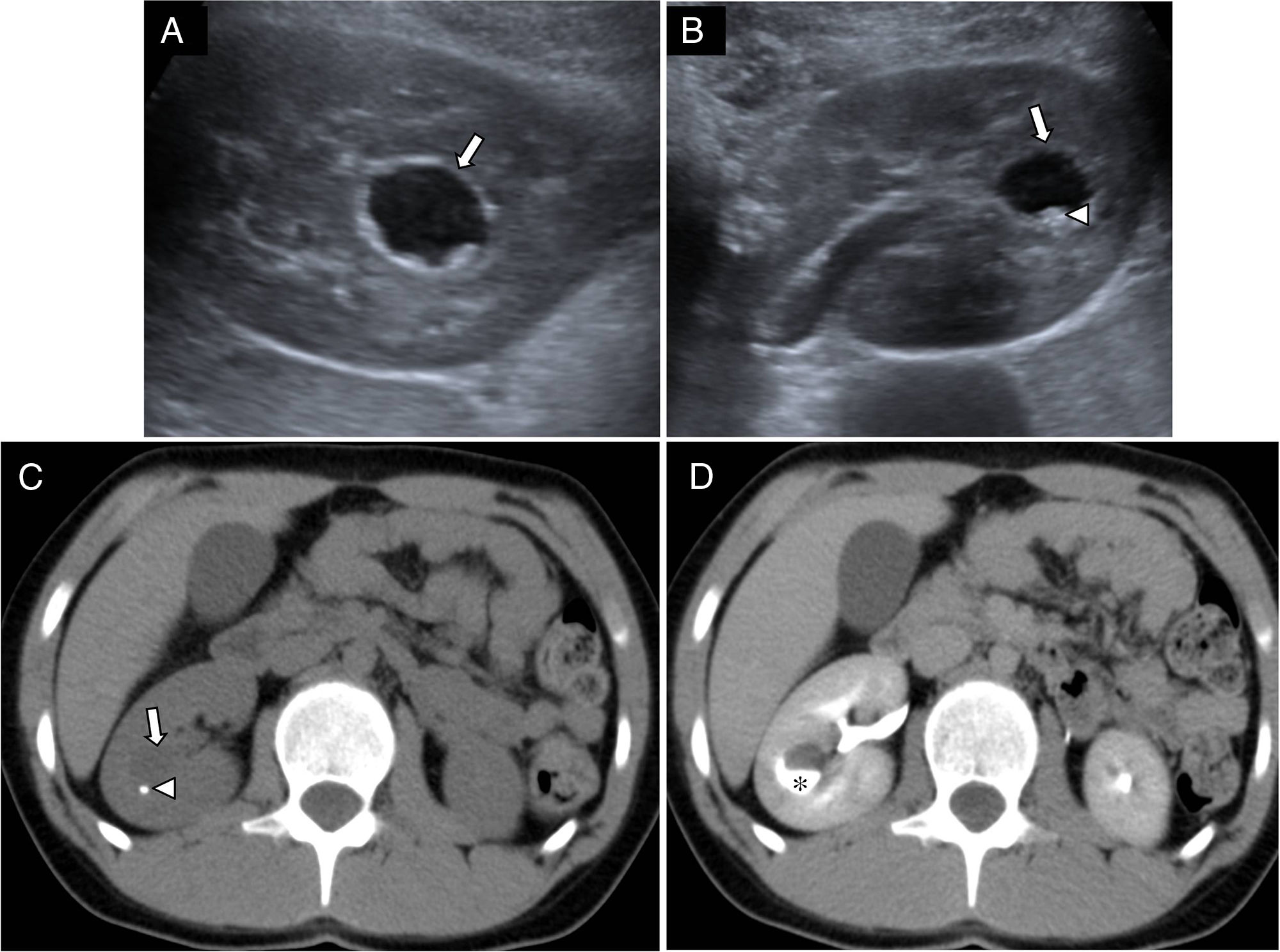

The most common complication in 30–50% of the cases is intradiverticular lithiasis (Figs. 3 and 4) favored by urine stagnation in the cystic cavity.1,2,5,8 It seems clear that in their formation other metabolic factors such as hypercalciuria, hyperuricosuria, or hyperoxaluria play an important role, which is why these factors should always be studied when finding CD. The composition of most intradiverticular stones is mixed: calcium oxalate monohydrate and hydroxyapatite.9

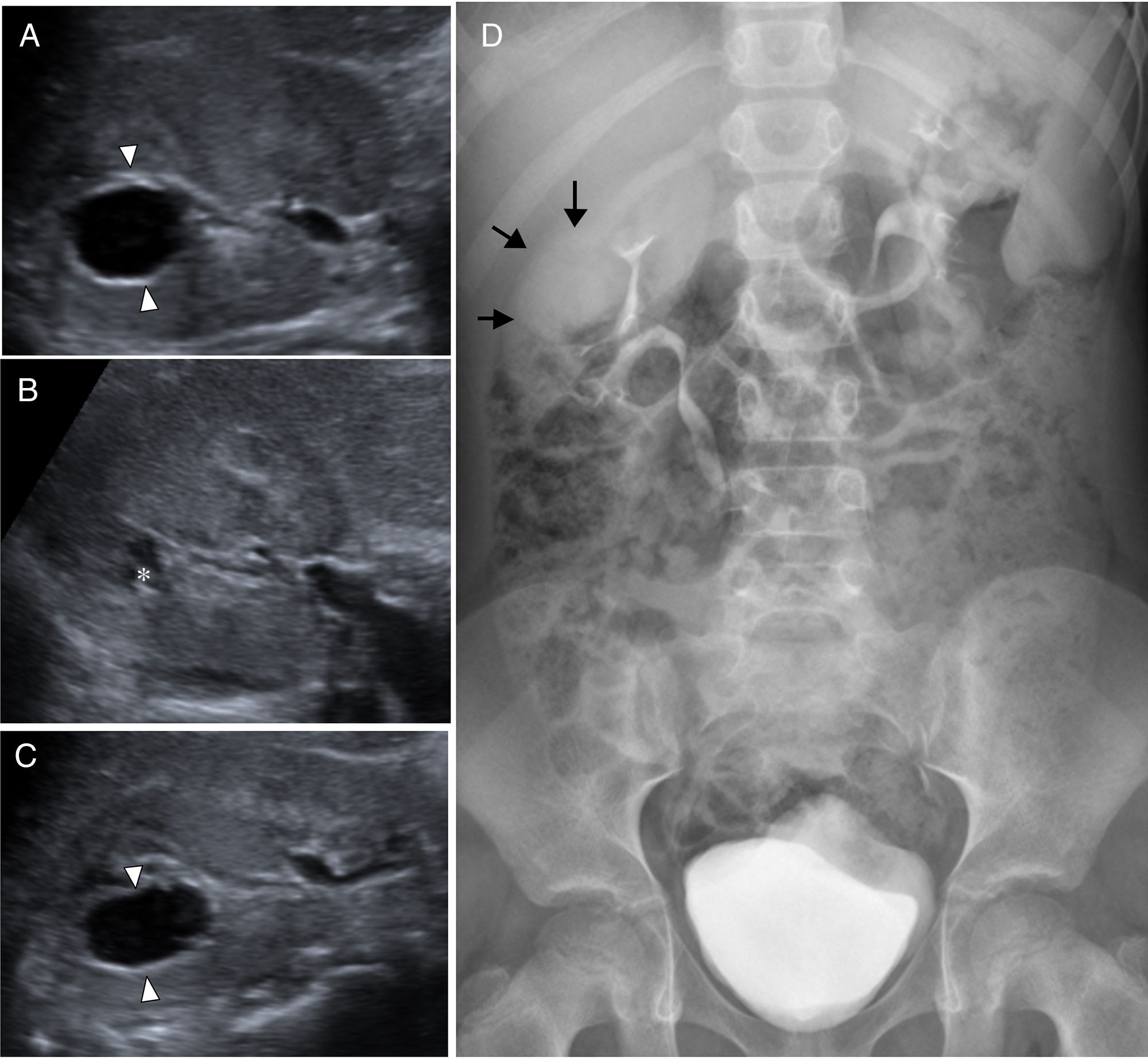

Ten-year-old girl with urinary tract infection. (A and B) Longitudinal and transversal slices of abdominal B mode ultrasonography of the right kidney showing one anechoic lesion with well-established walls in the middle third (arrows). Echogenic image with acoustic shadow in the declive portion of the cyst consistent with lithiasis (arrowhead). (C) Transversal view of abdominal CT scan without contrast confirming the image of lithiasis in the kidney (arrowhead) inside the cystic lesion (arrow). (D) CT scan with contrast in the excretory phase at 5min showing contrast (asterisk) inside the cystic cavity confirming the diagnosis of calyceal diverticulum with lithiasis.

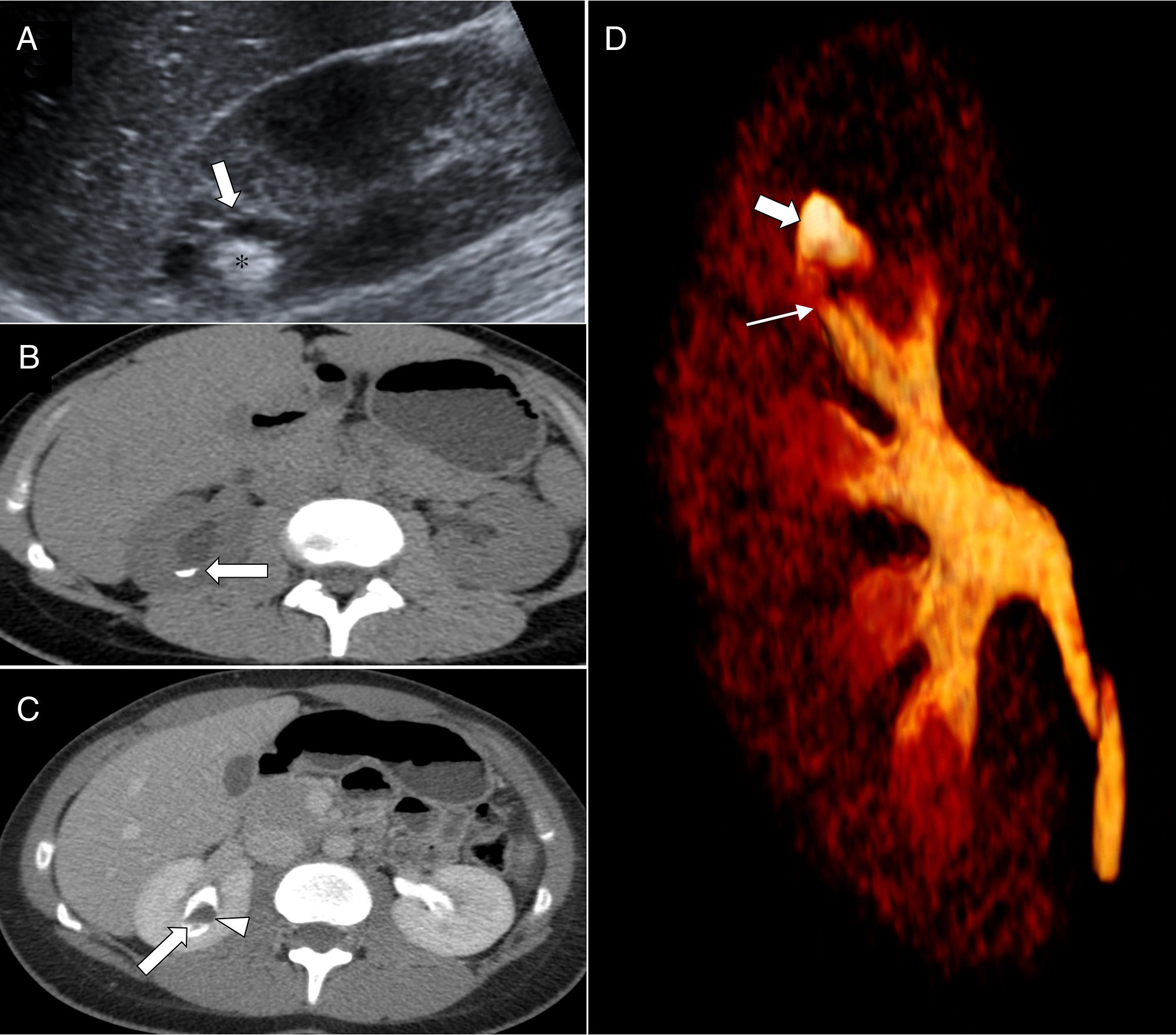

Nine-year-old girl with abdominal pain with colicky right flank pain (A) longitudinal view of the abdominal B mode ultrasonography of the right kidney showing one anechoic lesion in the upper pole (arrow) with echogenic content inside (asterisk) without a clear evidence of acoustic shadow. (B) Transversal view of abdominal CT scan without contrast with evidence of hyperdense content in semilunar shape inside one cystic lesion confirming level of contrast (arrow). (C) Transversal view of abdominal CT scan in the excretory phase at 5min showing contrast filling up the cystic lesion (arrow), presence of fluid and repletion defect. Findings show lithiasis of calyceal milk inside one calyceal diverticulum (arrowhead). (D) MIP and volumetric reconstructions showing the calyceal diverticulum (thick arrow) from a minor calyx (thin arrow) of the right upper group.

CD predispose to recurrent urinary tract infections that can become complicated with the formation of abscesses (Fig. 5). The narrow isthmus or infundibulum occludes, urine stagnates, and infection develops. The concomitant association of vesicoureteral reflux in some of these cases contributes to the infection. In the presence of CD, one urosonography should be conducted.7,10,11

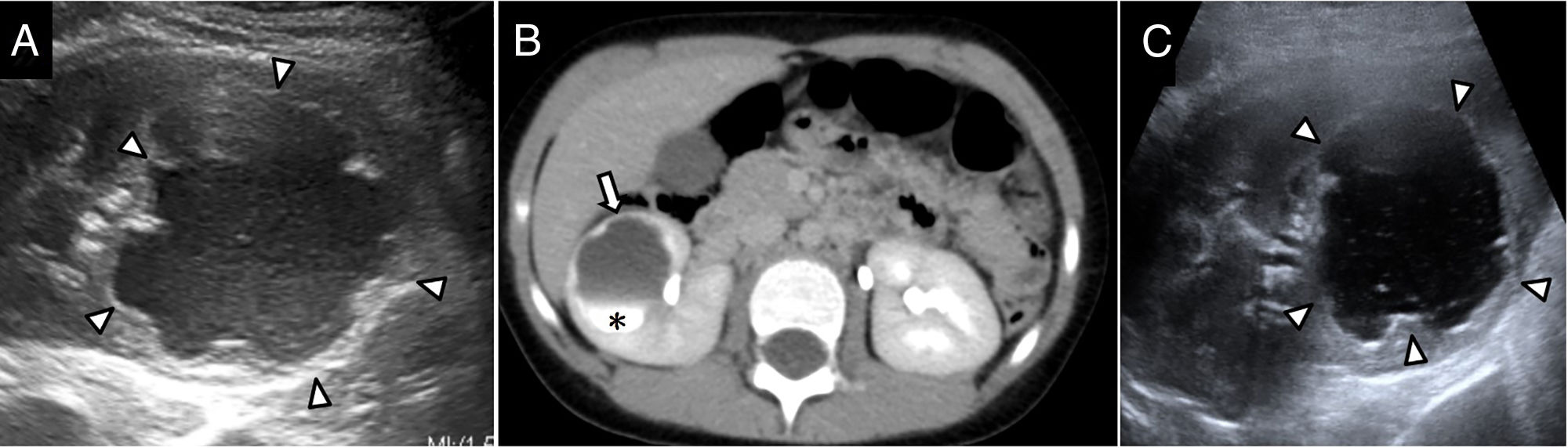

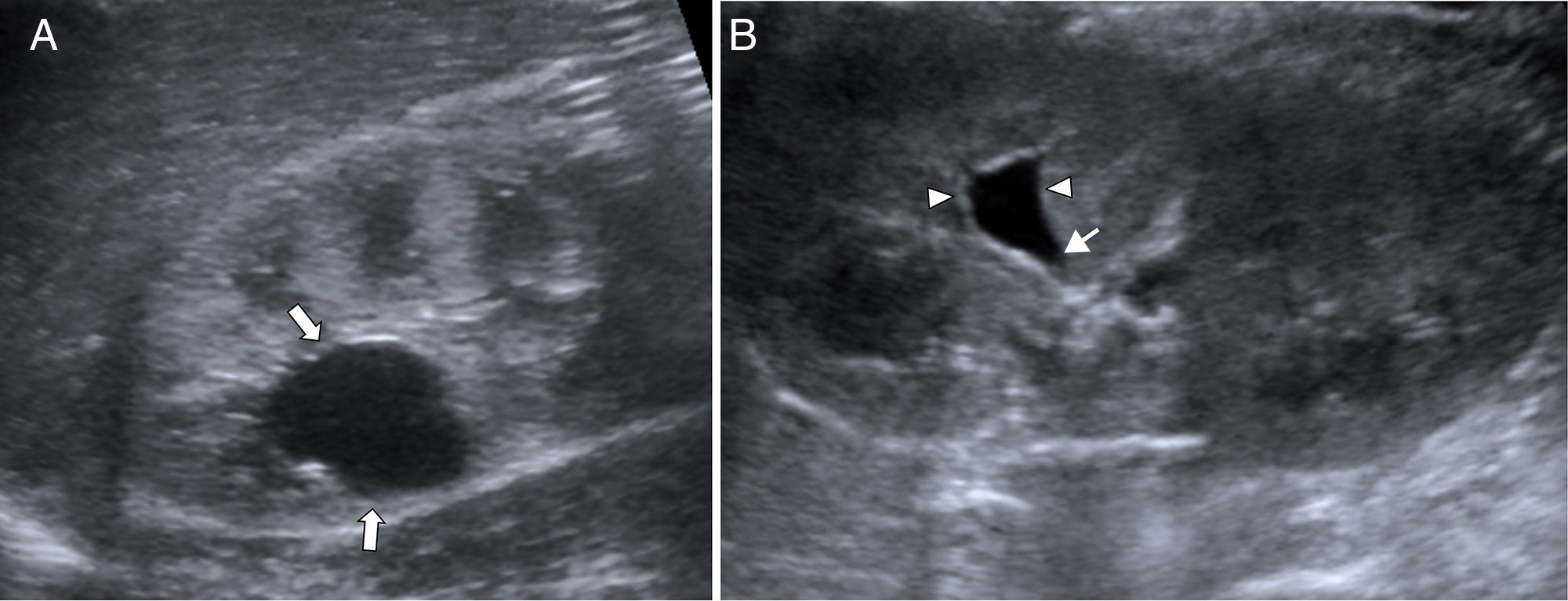

Five-year-old girl with urinary tract infection. (A) Longitudinal view of B mode ultrasonography in prone position showing one polylobulated cystic lesion in the middle-inferior third of the right kidney with dispersed echoes inside, suggestive of overinfected calyceal diverticulum (CD) given the clinical manifestations (arrowheads). (B) Abdominal CT scan in the excretory phase at 5min showing the lesion filling up with contrast (asterisk) confirming the diagnosis of CD. (C) Control ultrasound after antibiotic therapy showing the resolution of echoes inside the diverticulum while keeping the polylobulated shape (arrowheads).

Occasionally, they can be accompanied by hematuria following abdominal trauma with presence of intradiverticular bleeding (Fig. 6) being rupture an exception here.12

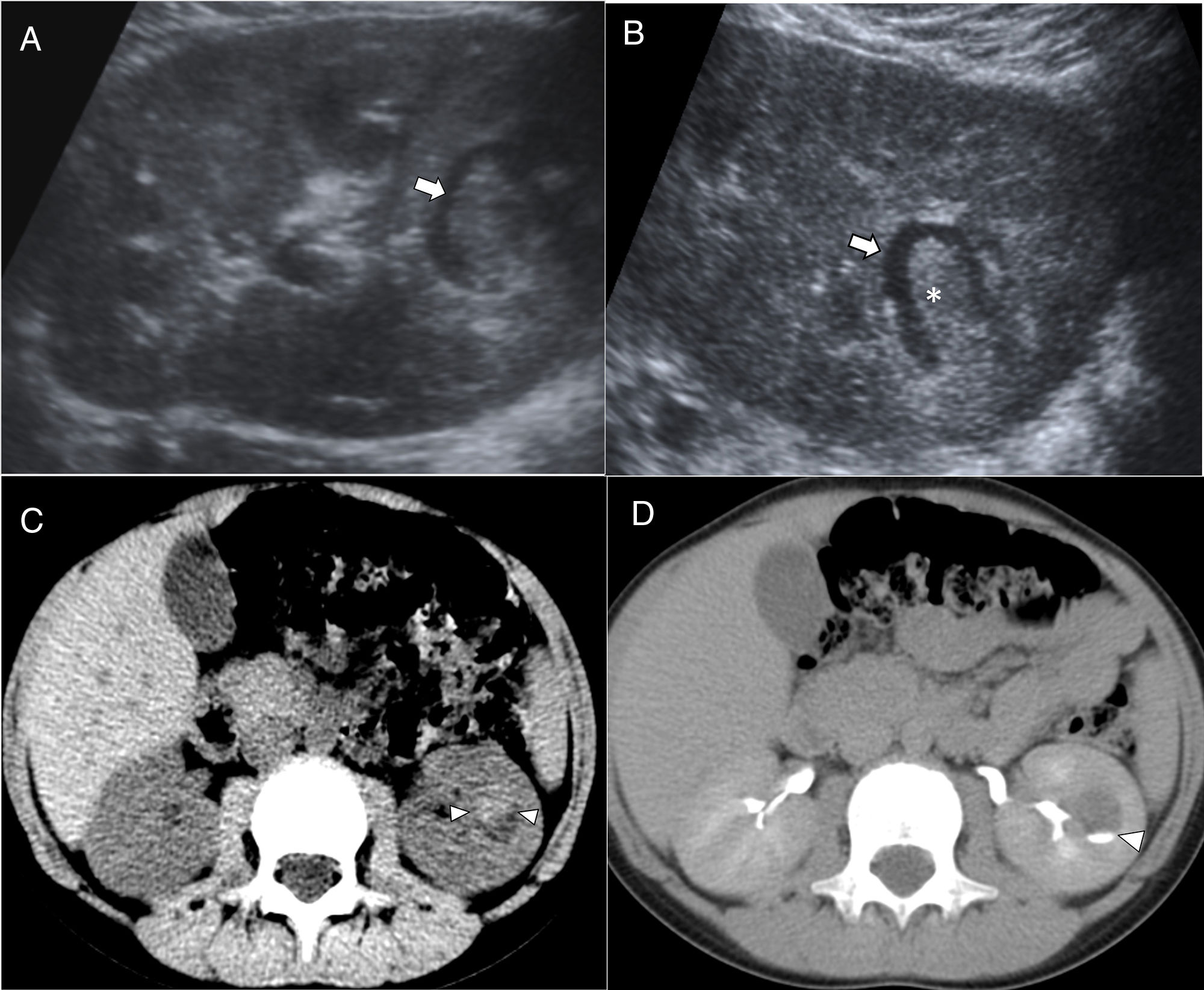

Nine-year-old boy with hematuria after mild abdominal trauma. (A) Abdominal B mode ultrasonography conducted in the supine position showing one anechoic lesion in the inferior third of the left kidney (arrow) with echogenic content inside. (B) Ultrasound in the prone position with content moving inside the lesion (asterisk). (C) Abdominal CT scan without contrast confirming the presence of blood content with level inside the cystic lesion (arrowheads). (C) Abdominal CT scan in the excretory phase at 5min showing contrast inside lesion (arrowhead) consistent with one calyceal diverticulum.

We should remember that during pediatric age, intradiverticular lithiasis is the most common complication of all.

Radiological findingsThe ultrasound is the imaging modality of choice for the study of kidneys in children. CD have the appearance of a well-established structure of thin walls that is anechoic due to its content in urine. The first diagnostic impression is that of a simple renal cyst, which is why other ultrasound criteria should be taken into consideration before confirming CD. The ultrasound view of the infundibular path between the cystic lesion and the excretory system is diagnostic (Fig. 7), but it is not always present. The change of size of a lesion initially considered as a simple cyst helps diagnose CD because it implies communication with the excretory system (Figs. 8 and 9). The presence of mobile hyperechogenic material within one renal cystic structure is the most commonly described diagnostic finding of CD.3,5,13–15 Based on our own personal experience, we take into consideration other ultrasound findings that also help diagnose CD: the “cloud” or polylobulated appearance and the variation in the morphology of the cystic lesion among different studies, or even in the same study by jut changing the child from the supine to the prone position. Although the suspicion of CD can be established through an ultrasound, it requires confirmation before conducting follow-up and planning a possible surgical treatment.2,13,16

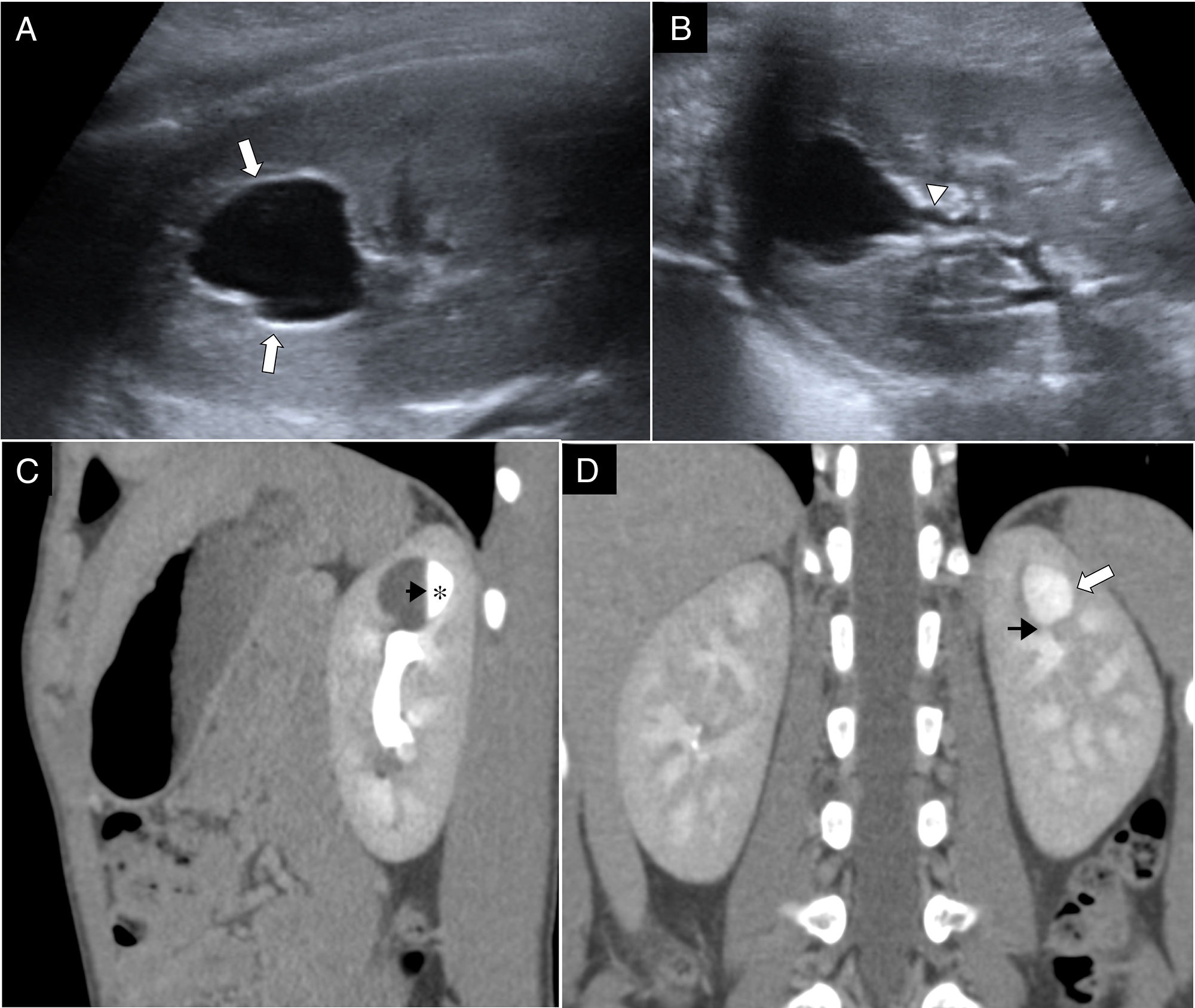

Seven-year-old boy with vomits operated one month ago due to Meckel's diverticulum. (A) Longitudinal view of abdominal B mode ultrasonography in the supine position showing one anechoic, polylobulated lesion in the upper pole of the left kidney (arrows). (B) Ultrasound study in the prone position showing morphological change and evidence of infundibular structure toward the excretory pathway (arrowhead). (C) Sagittal reconstruction of the abdominal CT scan in the excretory phase with filling of the calyceal diverticulum (asterisk) forming fluid-fluid level (black arrow). (D) Coronal reconstruction of the CT scan with contrast showing the connection (black arrow) between calyx and diverticulum (white arrow).

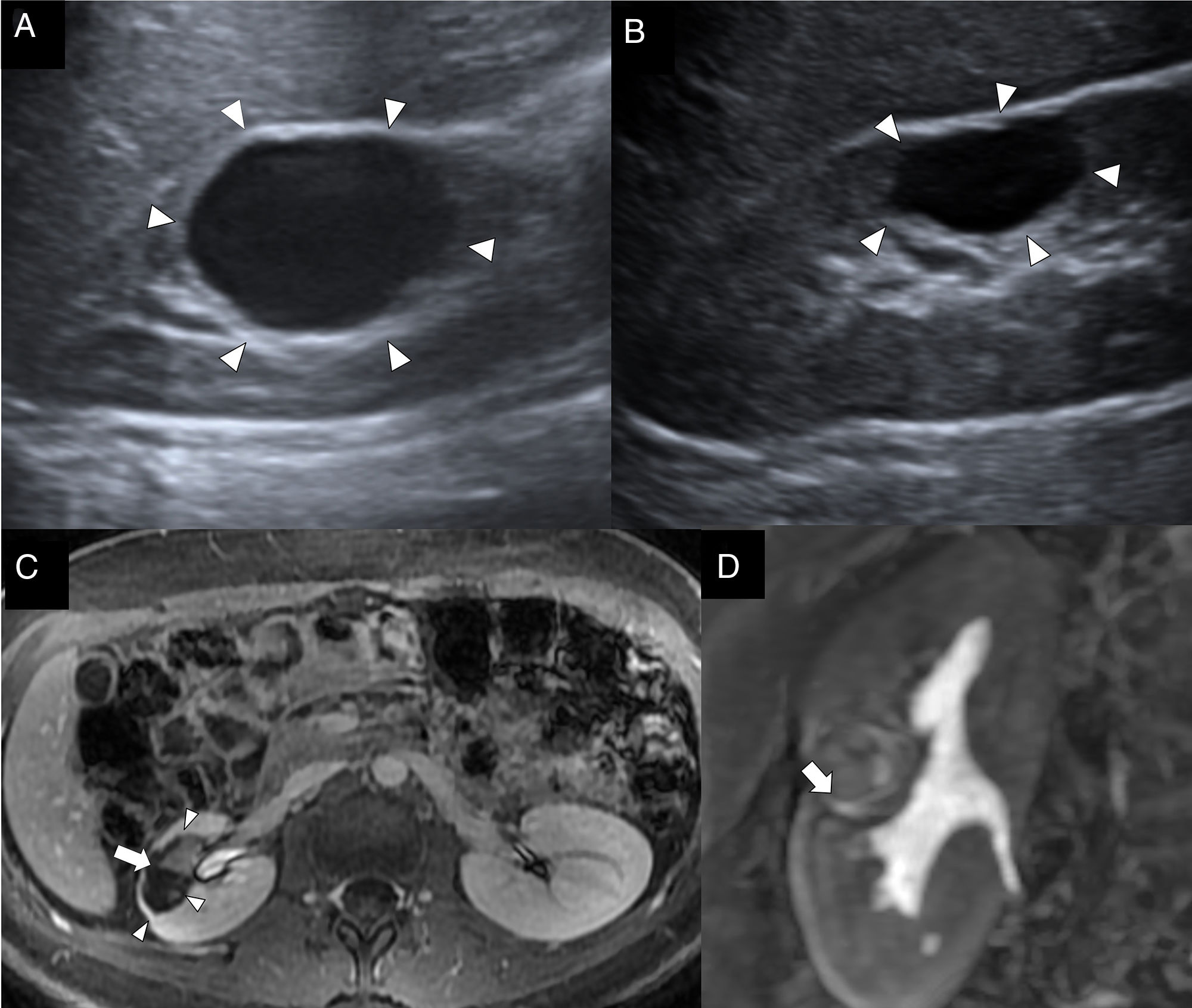

Seven-year-old boy without a prior history of recurrent abdominal pain. (A) Transversal view of the abdominal B mode ultrasonography of the right kidney showing one anechoic interpolar lesion that is interpreted as a simple renal cyst (arrowheads). (B) Control ultrasound at one year showing a significant reduction in the size of the cystic lesion with irregular morphology. (C) At the two-year control, the cystic lesion has increased in size. The change of size suggests communication with the excretory pathway. (D) Simple abdominal X-ray after CT scan with contrast confirming the presence of contrast material (arrows) filling up the cystic cavity in relation to the calyceal diverticulum.

Premature 36-week-old infant without a prior history. Control study due to prematurity at 7 weeks of life. (A) Longitudinal view of the abdominal ultrasound in the supine position showing one anechoic lesion in the posterior-superior side of the right kidney (arrows). (B) Ultrasound control at 18 months in the prone position; the lesion (arrowheads) has changed its shape, and there is one infundibulum aiming toward the excretory pathway of the sinus (arrow). Ultrasound findings highly suggestive of calyceal diverticulum. The child remains asymptomatic and given the need for sedation to conduct CT scans or the MRIs, it is decided to conduct annual ultrasound controls.

The intravenous urography, traditionally used to show the retrograde passage of contrast from the IV to the diverticulum, has now become old and has been replaced by the CT scan or MRI in the excretory phase.5,6,14

The CT scan in the excretory phase (starting at 5min) is the most commonly used imaging modality to confirm the existence of CD with a 95% sensitivity2 showing the passage of contrast to the renal cystic cavity. Usually, when there is suspicion of diverticulum complicated with lithiasis on the ultrasound, one pre-contrast phase is conducted for identification purposes. On the CT scan with contrast in the early phase, diverticula appear as small round areas of low-attenuation and adjacent to the calyxes, but this is not enough if we want to be completely sure about the diagnosis. The slight increase in the density of the diverticular content in the parenchymatous phase can be misdiagnosed as an enhanced solid portion of a tumor.1,13 For this reason, the diagnosis of cystic renal lesions on the pediatric CT scan should always include images in the excretory phase.1,2,5,7,13 Conducting different phases (pre-contrast, nephrographic and excretory) is questionable due to the high doses of radiation involved, being the CT scan in the excretory phase, the only diagnostic phase. The multi-slice CT scan provides reconstructions for diagnostic purposes, but also to plan the therapy by assessing the thickness of the infundibulum (narrow or wide) and the size of lithiasis (Figs. 2–7).

The MRI is an alternative imaging modality that avoids the use of ionizing radiation, but its availability and need for sedation make it the least used imaging modality of all. Same as it occurs with the CT scan, it requires a late-phase study to be diagnostic (Fig. 10). The MRI provides multiple planes to be able to outline the diverticula and their infundibulum and establish the connection with the pyelocalicial system.3,6

Eleven-year-old girl with recurrent infections. (A) Sagittal slice of the abdominal B mode ultrasonography of the right kidney showing one cystic lesion in the middle third (arrowheads) adjacent to the renal sinus that is interpreted as a simple cyst. (B) Control ultrasound at 2 years showing reduced sized of the lesion (arrowheads). Given the recurrence of urinary tract infections, one MRI is conducted. (C) MRI with contrast, transversal view on the T1-weighted sequence after the administration of contrast, early/nephrogenic phase outlining the cystic lesion (arrowheads) and level inside (arrow). (D) In the late/excretory phase at 10min, there is presence of contrast inside the cavity (arrow).

CD can be misdiagnosed as renal tumors when using positron emission tomography with F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET). The tracer accumulates in the diverticulum showing intense areas of focal uptake. Since the PET-TC has become so popular these days, it is important to consider this as a possible error and correlate the PET and CT findings.5

We should remember that the connection between the cystic image and the collecting system is a key diagnostic finding.

Differential diagnosisDifferential diagnoses include hydrocalyx, simple cyst, parapyelic cyst, papillary necrosis, renal abscess, and more rarely, autosomal dominant polycystic renal disease in the case of bilateral CD.2,3,6,13,17

Hydrocalyx is the dilation of a calyx due to infundibular obstruction. The most common cause during childhood is polar blood vessel and it is difficult to distinguish it from CD type I. Hydrocalyx is located in the normal position of a calyx, while the CD is located in the corticomedullary region leaving the excretory system intact.6

Simple cysts are unilocular and they do not connect to the pyelocalicial system, which is why they do not contain urine. One spherical configuration allows us to distinguish them from CD. Parapyelic cysts, that can be taken for CD type II due to their central location, do not communicate with the collecting system.5,6,14,16

Papillary necrosis is due to the ischemic necrosis of one papilla or the entire renal pyramid and is located in the renal medulla. It is associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and in children after infectious processes, but rarely with systemic damage such as sickle cell anemia and diabetes mellitus.1

The renal abscess shows a wall with irregular thickening, and hypoattenuation on the CT scan of the surrounding renal parenchyma that should help us distinguish it from an overinfected or abscessified CD.1,3,5,6,14,18

We should remember that the simple cyst is the main differential diagnosis with the calyceal diverticulum and never contains urine because it does not connect to the excretory pathway.

TreatmentThe management of CD in the pediatric age depends on whether they are symptomatic or not.6,7,13 Asymptomatic CD only require ultrasound controls, whose regularity is still not well designed, so unless there is clinical indication due to the presence of symptoms, the ultrasound control is usually annual. On the contrary, symptomatic CD require therapy.6,14,18 The indications for surgery include chronic pain, recurrent infection of the urinary tract, macroscopic hematuria or reduced renal function. Thus, up to 40% of children with CD are operated.1,7,18 The actual practice involves techniques that are less invasive than open surgery.2,5–7 The endoscopic approach consists of the dilation of the infundibulum and the ablation of the diverticular cavity. It is right for patients with small diverticula, in particular those located in middle and upper poles.18 The laparoscopic approach is more aggressive and first includes argon plasma electrocoagulation with or without surgical closure of the ostium; it is considered for big, exophytic type II diverticula with thinning of renal parenchyma,18,19 and in complicated cases with lithiases for the extraction of these.1

The diagnosis of the type of CD is of paramount importance to plan the interventional approach, since the communication between the diverticulum and the collecting system allows endoscopic, instead of percutaneous access.2

ConclusionCD are rare in children. On the ultrasound, they appear as simple renal cysts. The connection between the cystic image and the collecting system confirmed by imaging studies facilitates the diagnosis. The ultrasound findings of CD are the presence of the isthmus between the excretory pathway and the cystic cavity, and the presence of mobile material inside. Confirmation comes through CT scan or MRI in the excretory phase only. Lithiasis is the most common complication of all. The standard management of diverticula during childhood includes ultrasound follow-up and conservative therapy and less frequently surgical intervention.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments with human beings or animals have been performed while conducting this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors confirm that in this article there are no data from patients.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors confirm that in this article there are no data from patients.

Authors' contribution- 1.

Manager of the integrity of the study: CSN and YOS.

- 2.

Study idea: CSN and YOS.

- 3.

Study design: CSN and YOS.

- 4.

Data mining: N/A.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: N/A.

- 6.

Statistical analyses: N/A.

- 7.

Reference: CSN and YOS.

- 8.

Writing: CSN and YOS

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant remarks: CSN, YOS, SPA, ASU and POL.

- 10.

Approval of final version: CSN, YO, SPA, ASU and POL.

The authors declare no conflict of interests associated with this article whatsoever.

Please cite this article as: Ochoa Santiago Y, Sangüesa Nebot C, Picó Aliaga S, Serrano Durbá A, Ortega López P. Divertículos caliciales en niños: hallazgos radiológicos y formas de presentación. Radiología. 2018;60:378–386.