This study aimed to determine the diagnostic performance of transabdominal pelvic ultrasonography and bone age in identifying the onset of puberty in girls at the Clínica Las Américas in Medellín, Colombia.

MethodsWe included girls aged ≤11 years referred to our clinic between March 2016 and March 2019 for signs of puberty. We compared the findings on pelvic and breast ultrasonography and bone age versus the baseline measurement of luteinizing hormone (LH) in serum, used as the reference standard for identifying the onset of puberty. We calculated the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and positive and negative likelihood ratios, analyzing subgroups of patients of different ages.

ResultsWe analyzed 43 patients. Ultrasound assessment of breast development had the highest sensitivity (94.1%) of all the imaging parameters evaluated, but its specificity was low. However, characteristics such as the length of the body of the uterus >3.0 cm and the presence of endometrial echoes were highly specific for identifying the onset of puberty, particularly in patients aged ≤8 years.

ConclusionPelvic ultrasonography, ultrasonographic assessment of Tanner stage of breast development, and the evaluation of bone age are useful tools for the imaging confirmation of the onset of puberty. The results of this study support the use of these techniques in clinical practice in the workup for pubertal disorders in girls.

El objetivo del estudio fue determinar el desempeño diagnóstico de la ecografía pélvica transabdominal, la evaluación del desarrollo mamario por ecografía y la edad ósea en la identificación del inicio de la pubertad, en población pediátrica femenina de la Clínica Las Américas, Medellín, Colombia.

MétodosSe incluyeron pacientes femeninas de 11 años o menos, remitidas entre marzo de 2016 y marzo de 2019 por la aparición de signos de inicio de la pubertad. Se usó como estándar de referencia para el diagnóstico de pubertad la medición basal de hormona luteinizante (LH) sérica, con la cual se comparó la ultrasonografía pélvica y mamaria, así como la edad ósea. Se realizaron cálculos de sensibilidad, especificidad, valores predictivos positivo y negativo (VPP y VPN), razones de verosimilitud (LR + y LR-) y análisis por subgrupos de edades.

ResultadosSe analizaron 43 pacientes. La evaluación ecográfica del desarrollo mamario demostró la sensibilidad más alta (94,1%) dentro de todos los parámetros de imagen evaluados, aunque con baja especificidad. No obstante, características como la longitud del cuerpo del útero mayor de 3,0 cm y la presencia de eco endometrial fueron altamente específicas para la identificación del inicio de la pubertad, particularmente en pacientes de 8 años o menos.

ConclusiónLa ecografía pélvica, la valoración ecográfica del Tanner mamario y la evaluación de la edad ósea son herramientas útiles para la confirmación por imagen del inicio de la pubertad. Los resultados de este estudio apoyan su utilización en la práctica clínica, en el abordaje de trastornos puberales en niñas.

Puberty is related to various morphological and functional changes as a consequence of the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis.1–3 The identification of these changes and their correlation with the age of onset is useful in differentiating between normal pubertal development and puberty variants, including the identification of patients with precocious puberty,4 which is defined as the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics before 8 years of age in girls.5 Early presentation of puberty (sexual characteristics between 8 and 9 years in girls) is also recognised, which is divided into a slow form, without significant growth acceleration, and a rapidly progressive form, characterised by accelerated epiphyseal maturation with a decreased final height, as well as psychological stress.6,7 Secondary sexual characteristics correspond to those changes that appear during puberty (axillary and pubic hair, body odour, breast development and accumulation of fat in the hips in girls, among others), unlike the primary sexual characteristics that are present at birth, such as the vagina and uterus in girls or the penis and scrotum in boys.8

It is known that, currently, puberty tends to have an earlier onset than previously reported, but most of these records come from descriptions of the age at menarche and from physical examination.9 In one study, the mean age at menarche among girls in the US was described as 12.34 years (12.06 years for non-Hispanic black girls,12.09 years for Mexican American girls, and 12.52 years for non-Hispanic white girls).10 Similarly, in the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, African American girls were 1.55 times more likely to have menarche before age 11 than white girls.9

Different clinical, laboratory and imaging tools have been used to differentiate between normal pubertal development and its variants, such as the Tanner development scale, the measurement of serum gonadotropins,11 the estimation of bone age, as well as the evaluation of breast development by ultrasound and transabdominal pelvic ultrasound in the case of girls.

The capacity of ultrasound to assess breast development, the anatomical characteristics of the internal genital organs and their association with the onset of puberty have been explored in previous studies. Variable results have been obtained in terms of diagnostic yield, but evidence generally favours the use of ultrasound in the approach to patients with suspected pubertal disorders.12–15

Despite the above, most studies were carried out in European and Asian populations, in addition to having used gonadotropin measurement after stimulation with GnRH analogues as a reference test. Although this test makes it possible to detect the activation of the hormonal axis that leads to puberty, in practice its use is usually reserved for cases in which there is disagreement between the clinical suspicion and the baseline measurement of luteinising hormone (LH), which currently constitutes the laboratory test of choice and criteria for establishing the onset of puberty.4

Given the absence of data in the Hispanic population, the evidence that points to racial differences in pubertal development,16,17 the higher frequency of pubertal disorders in females, and taking into account that the onset of menarche at around 11–12 years in different populations is considered a defining sign of puberty, in this study we aim to determine the diagnostic yield of transabdominal pelvic ultrasound, evaluate breast development by ultrasound, and identify the onset of puberty by determining bone age using carpogram analysis in a female paediatric population (mixed-race, white and black Hispanic girls) at the Clínica Las Américas, in the period between March 2016 and March 2019.

Materials and methodsAnalytical, cross-sectional observational study carried out at the Clínica Las Américas, a hospital offering highly specialised services in the city of Medellín, Colombia, between March 2016 and March 2019. Inclusion criteria were female patients under 11 years with signs of the onset of puberty such as the appearance of axillary or pubic hair, breast development, and acceleration in growth rate that had also been evaluated with baseline serum LH measurement, pelvic and mammary ultrasound, and bone age. Patients with central nervous system alteration, the presence of chronic disease or peripheral precocious puberty based on the review of the medical records were excluded.

Bone age was evaluated by means of radiographs of the left hand (carpogram), according to the digital bone age atlas published by Oxford University Press, which modifies the Greulich and Pyle18 atlas, considering a difference of more than two standard deviations (SD) to be accelerated or advanced growth for the age.15

All transabdominal pelvic ultrasound studies were performed by two radiologists with 3 and 15 years of experience in paediatric radiology, respectively, using a 6 MHz convex transducer with a full bladder. Each patient was evaluated only once by one of the two radiologists, who were unaware of the laboratory results and other data from their medical history.

Uterine measurements included uterine length and corpus-cervix ratio (C:C) (anteroposterior diameter of the body divided by the anteroposterior diameter of the cervix).

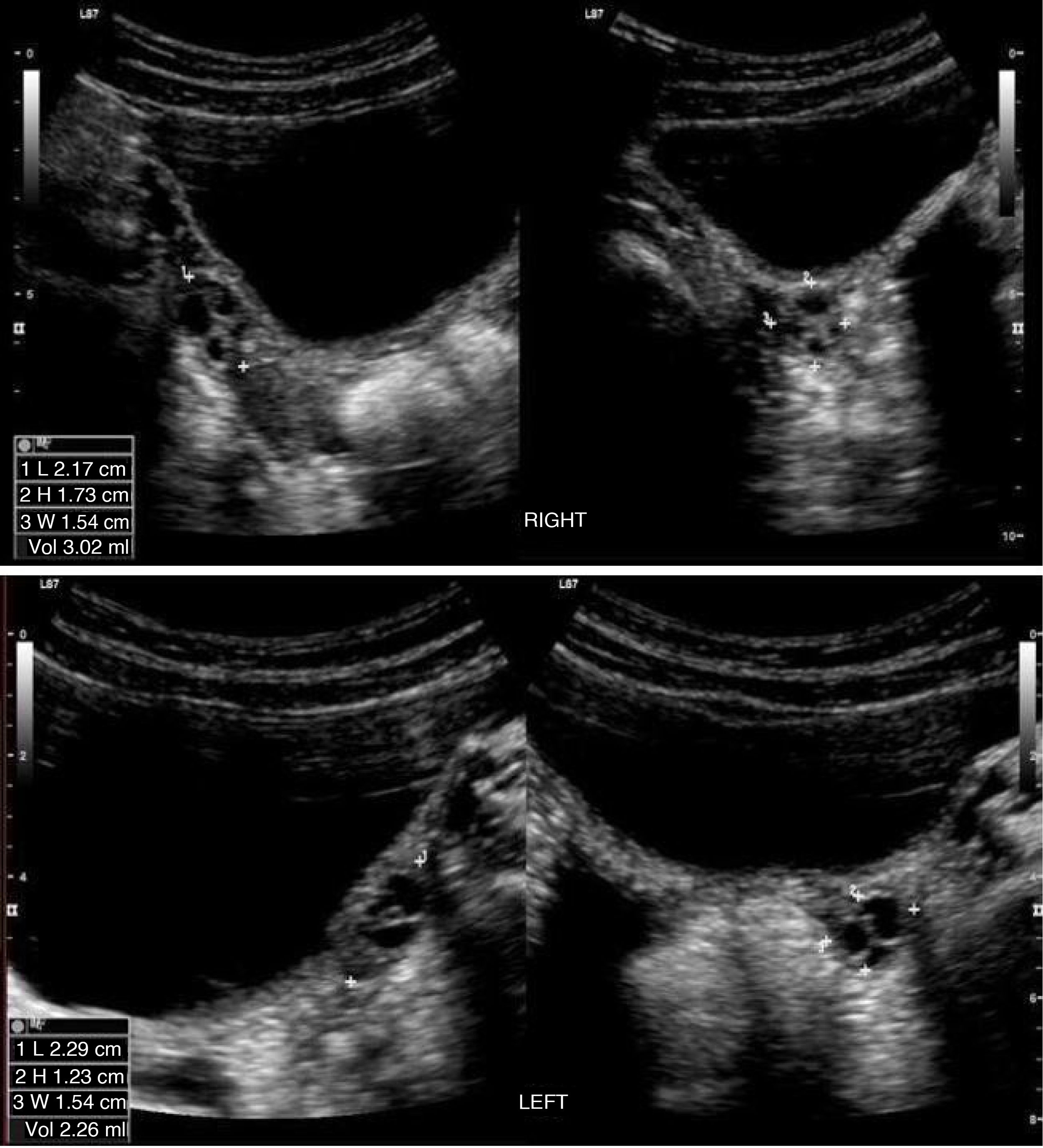

Ovarian volume was also determined using the ellipsoid formula: V (cm3) = longitudinal diameter (cm) × transverse diameter (cm) × anteroposterior diameter (cm) × 0.5236.

A uterine length greater than 3 cm, a C:C ratio ≥2:1, the presence of endometrial echogenicity, and an ovarian volume of more than 2 cm3 (averaging the volumes of both ovaries) were considered evidence of puberty.19 The number and size of the ovarian follicles were not assessed.

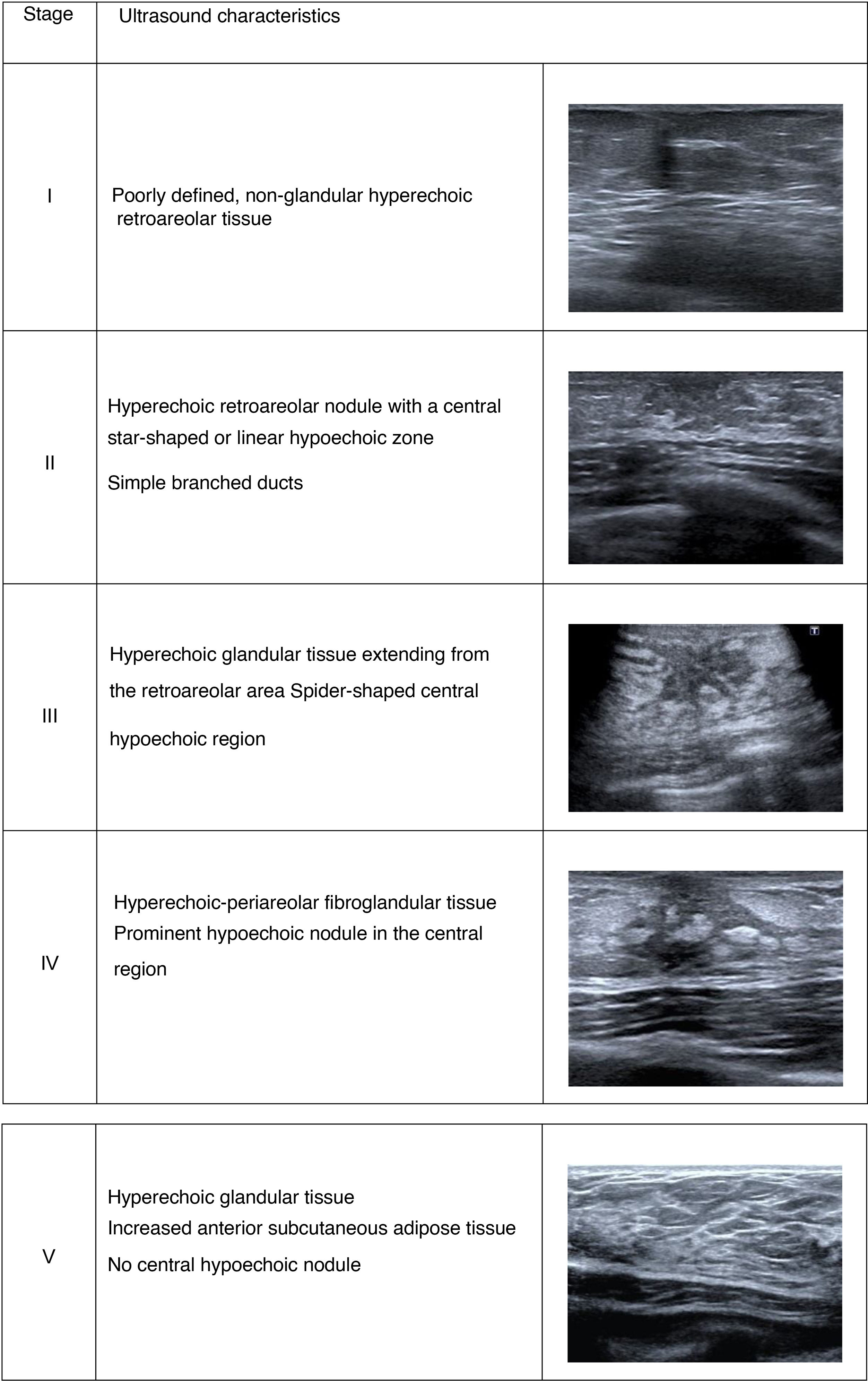

The ultrasound evaluation of the Tanner stage of breast development was performed with a 12 MHz linear array transducer, classifying the patients into 5 stages of development according to characteristic ultrasound findings20,21 (Fig. 1). Stage II and upwards was considered an indicator of pubertal development.

The reference standard used for diagnosis was the baseline serum LH concentration (random measurement), using a cut-off point greater than 0.3 U/L, for which a specificity close to 100% and a sensitivity of 90% has been reported in the scientific literature.22 Although concentrations of FSH and serum estradiol were also measured, these were not taken into account in the statistical analysis.

The information was obtained from the program used for reporting radiological and ultrasound images and data from the clinical laboratory of Clínica Las Américas, with a time interval of no more than 3 months between the acquisition of the images and the laboratory results.

The analysis was carried out using the program Stata version 14. in accordance with the proposed objectives. Absolute and relative frequencies were used to describe qualitative variables, and standard deviation or median and interquartile ranges for the quantitative variables, according to their distribution in the study population. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values (PPV and NPV) likelihood ratios (LR+ and LR−) were calculated, as well as analyses by age subgroups.

The investigation was approved by the hospital’s Ethics Committee, and adhered to the principles of research ethics contained in the Declaration of Helsinki and Resolution 008430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia. Informed consent was obtained from the legal guardians of the patients for the use of the data.

ResultsDuring the study period, 181 patients who underwent transabdominal pelvic ultrasound were selected for the evaluation of the onset of puberty. Of these, 76 patients were excluded for not having information on bone age or Tanner breast development stage by ultrasound, as well as 59 patients without laboratory data and 3 who did not agree to participate in the study. Finally, 43 patients were included in the analysis.

The mean age was 8.8 years (SD: 1.4), with a range between 6 and 11 years Of the girls included,17 were 8 years old or younger and 26 were older than 8 years. The diagnosis of onset of puberty was confirmed in 17 patients according to the LH value, corresponding to 39.5% of the sample, of which 4 were 8 years old or younger and therefore were considered to present precocious puberty. The ultrasound and laboratory findings of the study population are summarised in Table 1.

Ultrasound and laboratory findings of the study population.

| Variable | Value |

|---|---|

| Uterus | |

| Uterine corpus length (mm), Me (IQR) | 18 (14–22) |

| Uterine corpus:cervix ratio, X (SD) | 1.1 (0.3) |

| Ovaries | cm3, Me (IQR) |

| Right ovary volume | 1.5 (1–2.6) |

| Left ovary volume | 1.6 (1–2.3) |

| Tanner breast development | n (%) |

| Stage I | 13 (30.2) |

| Stage II | 24 (55.8) |

| Stage III | 6 (14) |

| Stage IV or V | 0 (0%) |

| Laboratory parameters | (U/l), Me (IQR) |

| Baseline LH | 0.24 (0.1–0.8) |

cm3: cubic centimetres; SD: standard deviation; Me: mean; mm: millimetres; n: number; IQR: interquartile range; U/l: units per litre; X: median.

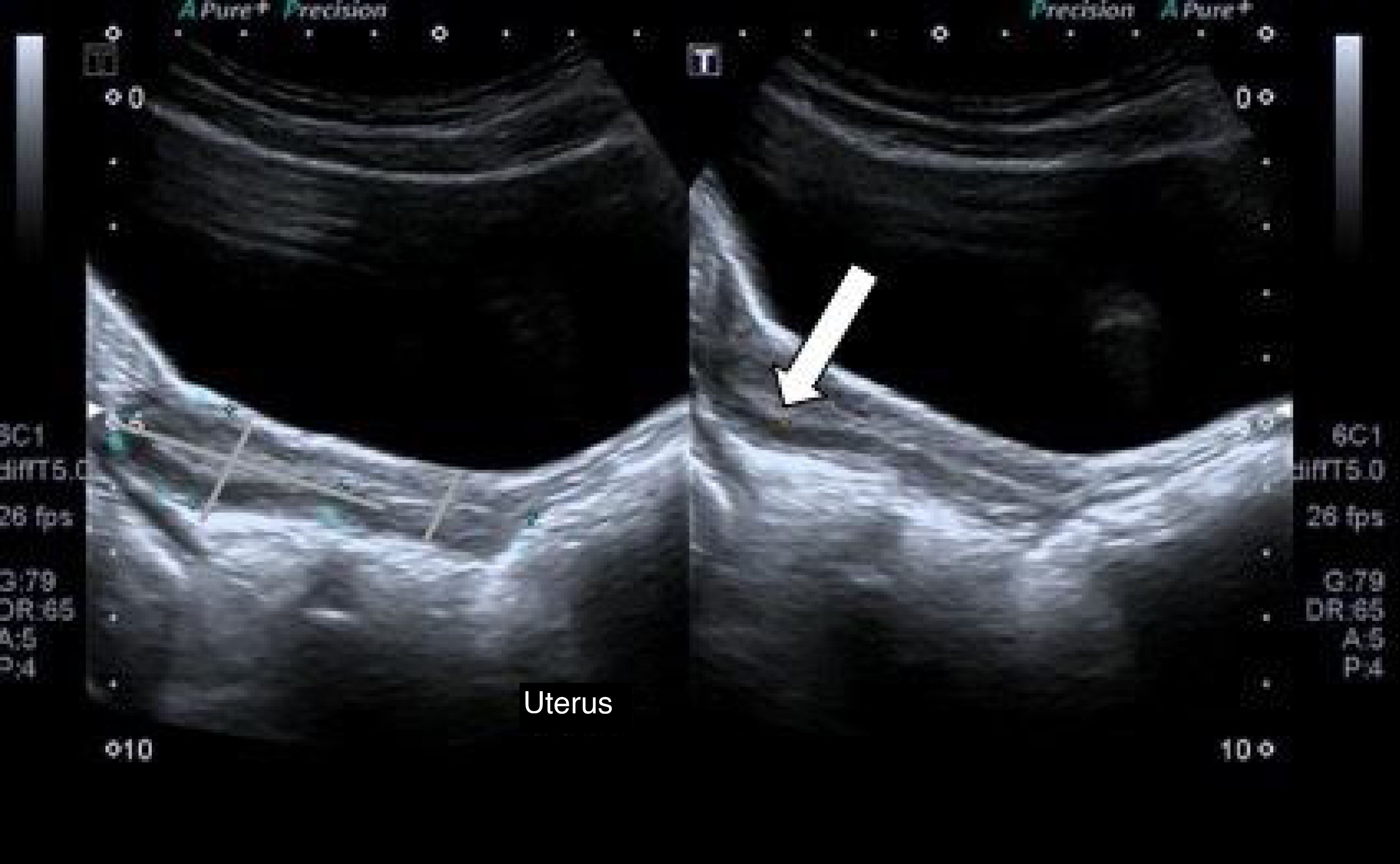

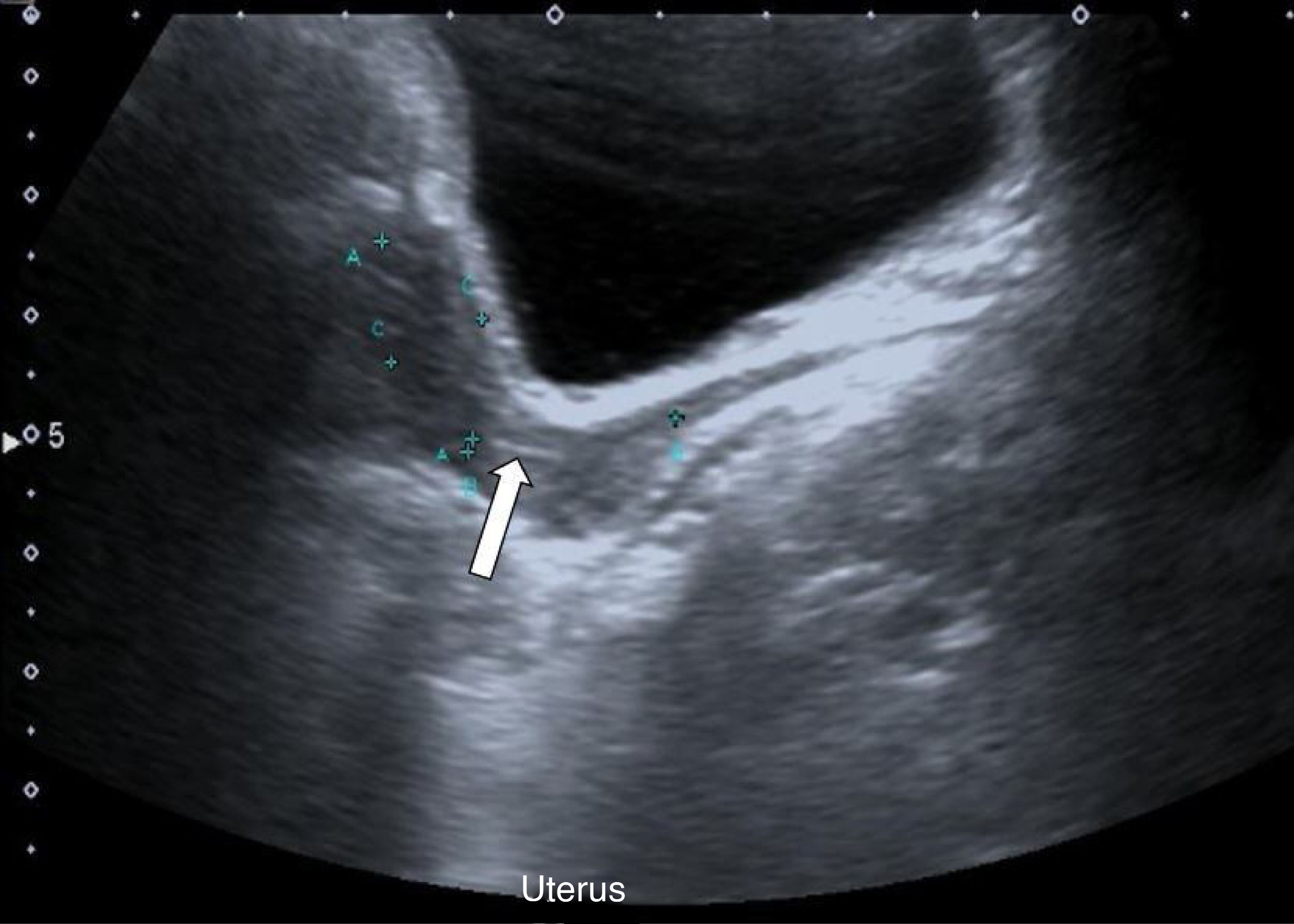

The diagnostic yield of the variables evaluated in comparison with the reference standard is summarised in Table 2. Within the parameters of pelvic ultrasound, the presence of endometrial echo, which was observed in 25.6% of the patients, had the highest sensitivity, with a value of 58.8%. Its specificity was 96.2%, with a PPV of 90.9%, an NPV of 78%, a positive LR of 15.3 and a negative LR of 0.4 (Figs. 2 and 3). When analysed by age subgroups, sensitivity increased to 75% in girls aged 8 years or younger, with a specificity of 100% (Table 3). Endometrial thickness was not reported.

Diagnostic performance of the evaluated variables compared to the reference standard.

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | LR+ (95% CI) | LR– (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial ultrasound | 58.8 (32.9–81.6) | 96.2 (80.4–99.9) | 90.9 (58.7–99.8) | 78.1 (60–90.7) | 15.3 (2.2–109) | 0.4 (0.2–0.8) |

| Uterine corpus length >3 cm | 23.5 (6.8–49.9) | 100 (86.8–100) | 100 (39.8–100) | 66.7 (49.8–80.9) | – | 0.8 (0.6–0.9) |

| Corpus:cervix ratio ≥2:1 | 17.6 (3.8–43.4) | 96.2 (80.4–99.9) | 75 (19.4–99.4) | 64.1 (47.2–78.8) | 4.6 (0.5–40.6) | 0.9 (0.7–1.1) |

| Ovarian volume >2 cm3 | 47.1 (23–72.2) | 76.9 (56.4–91) | 57.1 (28.9–82.3) | 69 (49.2–84.7) | 2 (0.9–4.8) | 0.7 (0.4–1.1) |

| Tanner breast ultrasound ≥II | 94.1 (71.3–99.8) | 46,1 (26,6–66,6) | 53.3 (43.9–62.4) | 92.3 (63.1–98.8) | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) | 0.1 (0.02–0.9) |

| Bone age ≥2 SD | 29.4 (10.3–56) | 96.2 (80.4–99.9) | 83.3 (35.9–99.6) | 67.6 (50.2–82) | 7.7 (0.9–59.9) | 0.7 (0.5–1.01) |

CI: confidence interval; cm3: cubic centimetres; LR: likelihood ratio; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; SD: standard deviation.

Transabdominal pelvic ultrasound showing the uterus with a longitudinal diameter of 20 mm and absence of endometrial echo, characterised as prepubertal. In our experience, linear echogenicity of the endocervical canal (arrow) aids in the identification of the transition point between the uterine corpus and the cervix in prepubertal patients.

Diagnostic performance of study variables compared with the reference standard in the subgroup aged 8 years or less (n: 17).

| Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | PPV (95% CI) | NPV (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrial ultrasound | 75 (19.4–99.4) | 100 (75.3–100) | 100 (29.2–100) | 92.9 (66.1–99.8) |

| Uterine corpus length >3 cm | 100 (39.7–100) | 100 (75.2–100) | 100 | 100 |

| Corpus-cervix ratio 2:1 | 25 (0.6–80.6) | 100 (75.3–100) | 100 (2.5–100) | 81.3 (54.4–96) |

| Ovarian volume >2 cm3 | 25 (0.6–80.6) | 92.3 (64–99.8) | 50 (1.3–98.7) | 80 (51.9–95.7) |

| Tanner breast ultrasound ≥ II | 100 (39.7–100) | 61.4 (31.5–86.1) | 44 (28.6–61.4) | 100 |

| Bone age >2 SD | 25 (0.6–80.6) | 92.3 (64–99.8) | 50 (1.3–98.7) | 80 (51.9–95.7) |

CI: confidence interval; cm3: cubic centimetres; NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value; SD: standard deviation.

A longitudinal measurement of the corpus of the uterus greater than 3 cm was the parameter with the highest specificity (100%) for the identification of the onset of puberty, with a sensitivity of 23.5%, a PPV of 100% and an NPV of 66.7%. Additionally, it was the marker with the highest sensitivity and specificity in the group of patients aged 8 years or younger, reaching values of 100%.

Similarly, a C:C ratio greater than or equal to 2:1 had a high specificity - 96.2% in the total sample and 100% in patients 8 years of age or younger. However, its sensitivity was very low and it did not show significant changes in the analysis by age subgroups.

Ovarian volume was the characteristic with least specificity in pelvic ultrasound, with a value of 76.9% and a sensitivity of 47.1% (Fig. 4).

Regarding the ultrasound evaluation of the Tanner breast development stage, almost 70% of patients were at a stage greater than or equal to II, a variable that demonstrated a sensitivity of 94.1% (95% confidence interval [CI], 71.3–99.8), and a specificity of 46.1% (95% CI, 26.6–66.6).

Bone age had a sensitivity of 29.4% (95% CI, 10.3–56) and a specificity of 96.2% (95% CI, 80.4–99.9).

DiscussionUnlike previous studies that have evaluated the ultrasound parameters of girls with precocious puberty and precocious thelarche, our study also took into account patients older than 8 years with physiological onset of puberty using baseline LH measurement as a standard for diagnosis, which is in line with current clinical practice recommendations.4,23,24

We show that most of the pelvic ultrasound parameters evaluated are highly specific, but insufficiently sensitive; this is consistent with the results published by de Vries et al.13 Similarly, a uterine corpus length greater than 3 cm and the presence of endometrial echo were the most useful characteristics (especially in the group of patients aged 8 years or younger), despite the fact that uterine thickness was not reported. Similar results were reported by Paesano et al. and Wen et al.25,26

However, in contrast to the study by Badouraki et al.27, where ovarian volume was considered the best indicator for the diagnosis of true puberty, our findings show that uterine measurements show better diagnostic performance, and that the specificity of ovarian volume is lower than that of the other characteristics evaluated. This discrepancy could be explained in part because not all the patients in the study in question underwent hormonal evaluation, and patients who had actually started puberty could have been included in the group of prepubertal patients. Therefore, not including patients with true puberty but low ovarian volumes in the analysis of pubertal patients could have falsely increased the specificity of this parameter. As mentioned above, the results of Wen et al.26 also show that uterine characteristics are the ones with the best precision.

The characterisation of breast development by ultrasound showed the highest sensitivity of all imaging parameters evaluated, although with a low specificity. Other authors have evaluated its capacity to differentiate between central precocious puberty and puberty variants or normal puberty. However, these studies have been based mainly on measuring the volume of fibroglandular tissue.15 Although potentially useful, calculating this volume is more complicated since it is necessary to adequately delineate the contours of the fibroglandular tissue, which could lead to greater intra- and interobserver variability. Measurements such as the diameter of the breast bud have been studied, and a limited capacity has been found to differentiate between central or true precocious puberty and premature thelarche.21

Regarding the estimation of bone age, studies such as that of Calcaterra et al.15 have shown intermediate sensitivities and specificities, taking a value greater than 2 SD as a cut-off point. Our results show that the diagnostic characteristics of bone age appear to be similar to those of breast development assessed by ultrasound. It is worth noting that in the above study, hormonal assessment was not used as the gold standard for establishing the diagnosis of puberty.

Our study has several limitations, among which is the relatively small sample size and a selection bias when including patients referred from the paediatric endocrinology clinic. In clinical practice, however, pelvic ultrasound is generally used in patients in a context similar to that of the present study

Finally, this study could serve as the basis for multicentre and prospective studies that make it possible to expand the sample size and obtain more accurate data from the local population.

ConclusionIn accordance with the foregoing, a uterine length of more than 3 cm and the presence of endometrial echo in patients aged 8 years or younger supports the suspicion of precocious puberty. However, its identification in patients aged 9 years or older is considered physiological, provided it is consistent with other elements of the clinical evaluation. In contrast to earlier studies, the results of our investigation suggest that ovarian volume is not the best indicator of true puberty. Moreover, the absence of glandular tissue on breast ultrasound makes it unlikely that the patient has initiated pubertal development.

In conclusion, pelvic ultrasound, ultrasound assessment of the Tanner breast development stage and bone age assessment are useful tools for confirming the onset of puberty, which in turn could be applied for the diagnosis of precocious puberty in the appropriate clinical context.

Authorship- 1

Persons responsible for the integrity of the study: JRA, MFS, MAL, JDO, MMTO.

- 2

Study concept: JRA, MFS, MAL, JDO, MMTO.

- 3

Study design: JRA, MFS, MAL, JDO, MMTO.

- 4

Data collection: JRA, MFS, MAL, JDO, MMTO.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: JRA, MFS, MAL, JDO, MMTO.

- 6

Statistical processing: N/A.

- 7

Bibliographic search: JRA, MFS, MAL, JDO, MMTO.

- 8

Drafting of the paper: JRA, MFS, MAL, JDO, MMTO.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: JRA, MFS, MAL, JDO, MMTO.

- 10

Approval of the final version: JRA, MFS, MAL, JDO, MMTO.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.