This article aims to show the usefulness of the pneumo-computed tomography gastric distention technique in the detection and morphological characterization of subepithelial gastric lesions. We correlate the pneumo-computed tomography and pathology findings in lesions studied at our institution and review the relevant literature.

ConclusionPneumo-computed tomography, combined with multiplanar reconstructions, three-dimensional reconstructions, and virtual endoscopy, is useful for delineating the morphological details of subepithelial gastric lesions, thanks to the additional gastric distention. This technique better delimits and characterizes the upper and lower margins of the lesions. Pneumo-computed tomography can be considered a useful noninvasive imaging techniques for characterizing these lesions.

El propósito de este artículo es destacar la utilidad de la técnica de distensión gástrica neumo-tomografía computarizada en la detección y caracterización morfológica de las lesiones subepiteliales gástricas estudiadas en nuestra institución, con su correlación de anatomía patológica y una revisión de la literatura.

ConclusiónLa neumo-tomografía computarizada combinada con las reconstrucciones multiplanares, las reconstrucciones tridimensionales y la endoscopia virtual es útil para delinear los detalles morfológicos de las lesiones subepiteliales gástricas debido a la distensión gástrica adicional. Se logra una mejor delimitación de sus bordes superior e inferior, así como las características de sus márgenes. Puede considerarse una técnica de imagen útil y no invasiva para la caracterización de estas lesiones.

A gastric subepithelial lesion (SEL) is defined as an elevated lesion or mass often with an intact mucosa.1 Previously known as submucosal lesions; they are currently described as subepithelial as they encompass lesions originating from any layer of the wall except the epithelium.2

These lesions are usually circumscribed with an intact mucosa and with an endoluminal, exophytic, or mixed growth pattern. Small lesions that arise in the submucosa usually protrude into the gastric lumen, and larger masses usually demonstrate exophytic growth.3

Most are found incidentally during routine endoscopy and are asymptomatic; others cause abdominal pain, haematochezia, melaena, or other symptoms if they are large or ulcerated.2

Once they are detected, it is important to advance in the diagnosis, there being different techniques with their own strengths and weaknesses.

Multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) with specific gastric distension (GD) protocols utilises oral contrast agents or effervescent granules prior to examination.4,5 Proper GD allows for the analysis of the following characteristics: location, attenuation, enhancement with intravenous contrast and growth pattern. However, GD performed with ingestion of water or effervescent granules may be suboptimal, and GD performed with hyperdense oral contrast may camouflage a lesion due to similar attenuation.6,7

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is useful for the detection of early-stage tumours as it assesses the penetration of the lesion and the presence of regional adenopathies, impacting the therapeutic strategy.8 However, it does not detect metastases in lymph nodes or distant solid organs and is limited in the presence of impassable oesophageal strictures. It is also a method that increases the time on the ward, is a less affordable procedure, increases morbidity and requires an experienced operator.9

Pneumo-computed tomography (pneumo-CT) uses CO2 as an alternative distension technique.10 It entails the transoral or transnasal introduction of a Foley catheter placed under the cricopharyngeal muscles, insufflating CO2 at a regulated, continuous, and sustained pressure automatically with an injection pump between 15 and 25 mmHg, in order to achieve adequate oesophageal and gastric distension. Once the maximum distension is obtained, acquisitions of the neck, thorax, abdomen, and pelvis are carried out. It does not require anaesthesia and only causes discomfort on insertion of the catheter.10

Multiplanar and three-dimensional reconstructions are then performed with different window configurations to allow visualisation of the lesion. In addition, virtual endoscopy provides a view from within the lumen.

The main indication for pneumo-CT is surgical planning regarding non-resectable lesions through endoscopy.10 With this technique, the surgeon has a prior representative iconography for planning the surgery, defining the upper and lower limits of the lesions, assessing the anatomical relationships, and detecting lymph node and distant organ metastases in a single study. It is also indicated when it is impossible to perform an EUS or when there is an oesophageal stenosis.10

In this article, we demonstrate the usefulness of pneumo-CT in the detection and morphological characterisation of gastric SELs studied in our institution through an anatomical-radiological correlation of cases, with a review of the literature.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumoursGastrointestinal stromal tumours (GIST) derive from the interstitial cells of Cajal and most commonly originate in the stomach (60–70%) and small intestine (30%); and rarely in the rectum, oesophagus, colon, or appendix.11 They occasionally originate outside the gastrointestinal tract, such as in the mesentery or omentum.

The gastric body is the most common site, followed by the fundus and the antrum (Fig. 1).12 GISTs smaller than 2 cm have low or no malignant potential.13

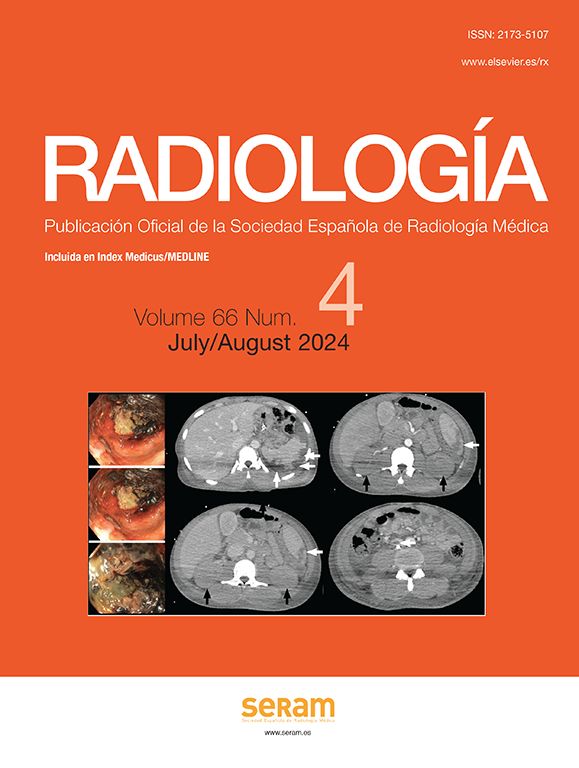

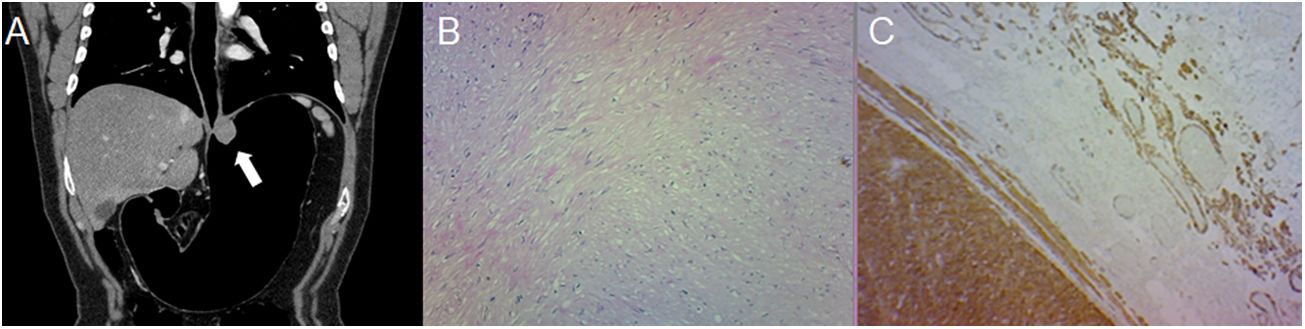

A 43-year-old male with an incidental finding of a lesion during a routine endoscopy. (A) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, a cross section revealing a homogeneous mass with endophytic growth in the gastric body (arrow). (B) Histology (×100; haematoxylin-eosin staining) revealing spindle cells arranged in intersecting fascicles. (C) CD117 immunoreactivity confirms the diagnosis of GIST. The main differential diagnosis is leiomyoma, which can only be distinguished by immunohistochemistry, even though they are more common in the oesophagus and gastric cardia.

Asymptomatic GISTs may be due to small size or an exophytic growth pattern. Mucosal ulceration can lead to gastrointestinal bleeding, including haematemesis, melaena, and iron deficiency anaemia.12

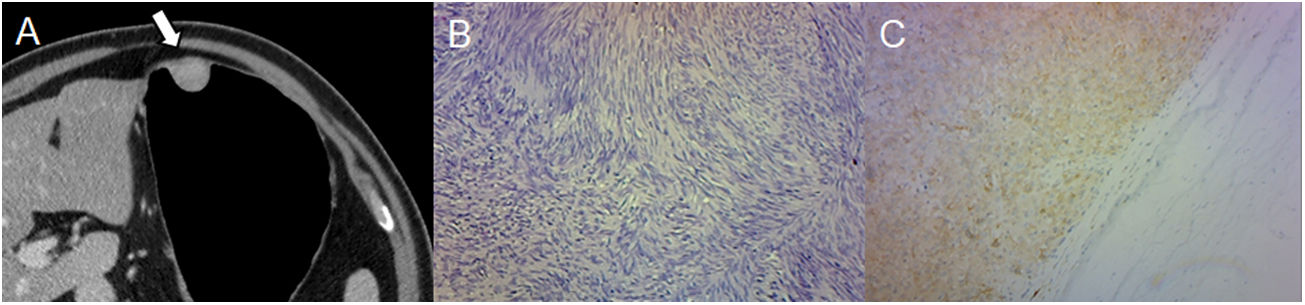

It should be borne in mind that GISTs usually have exophytic or intramural growth since they arise from the deep muscularis propria and endoluminal growth is less common.3 Appearance on MDCT depends on the size and aggressiveness of the tumour. Tumours smaller than 3 cm appear as a well-defined and homogeneous endoluminal or polypoid mass with soft-tissue attenuation and with varying degrees of enhancement.11 Large tumours have irregular margins, mucosal ulceration, hypervascular enhancement, and are heterogeneous due to necrosis, bleeding, or cystic degeneration.11,12 They often have vessels inside them and, rarely, calcifications (Fig. 2).3,12

Different presentations of GIST. (A–D) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, cross sections of different cases: maximum intensity projection (MIP) reveals vessels within the tumour (A) (arrow); heterogeneous mass due to central necrosis (B) (arrow); heterogeneous enhancement due to areas of cystic degeneration (C) (arrow); hypervascular enhancement in arterial phase (D) (arrow). (E, F) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, coronal reconstructions: calcification in the periphery of the tumour (E) (arrow); mucosal involvement causing central ulceration (F) (arrow).

Although they tend to displace adjacent organs and vessels, exophytic lesions can invade structures such as the pancreas, colon, or diaphragm.3

Metastases occur mainly in the liver and peritoneum, and less commonly in the lymph nodes, soft tissues, lungs, and pleura.14

Histologic analysis shows a tumour composed of spindle cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm and elongated nuclei, arranged in intersecting fascicles. GISTs show immunoreactivity for CD117 (c-KIT) and DOG1.

In summary, GISTs represent the majority of SEL, ranging from small intraluminal lesions to exophytic masses, with areas of bleeding or necrosis.

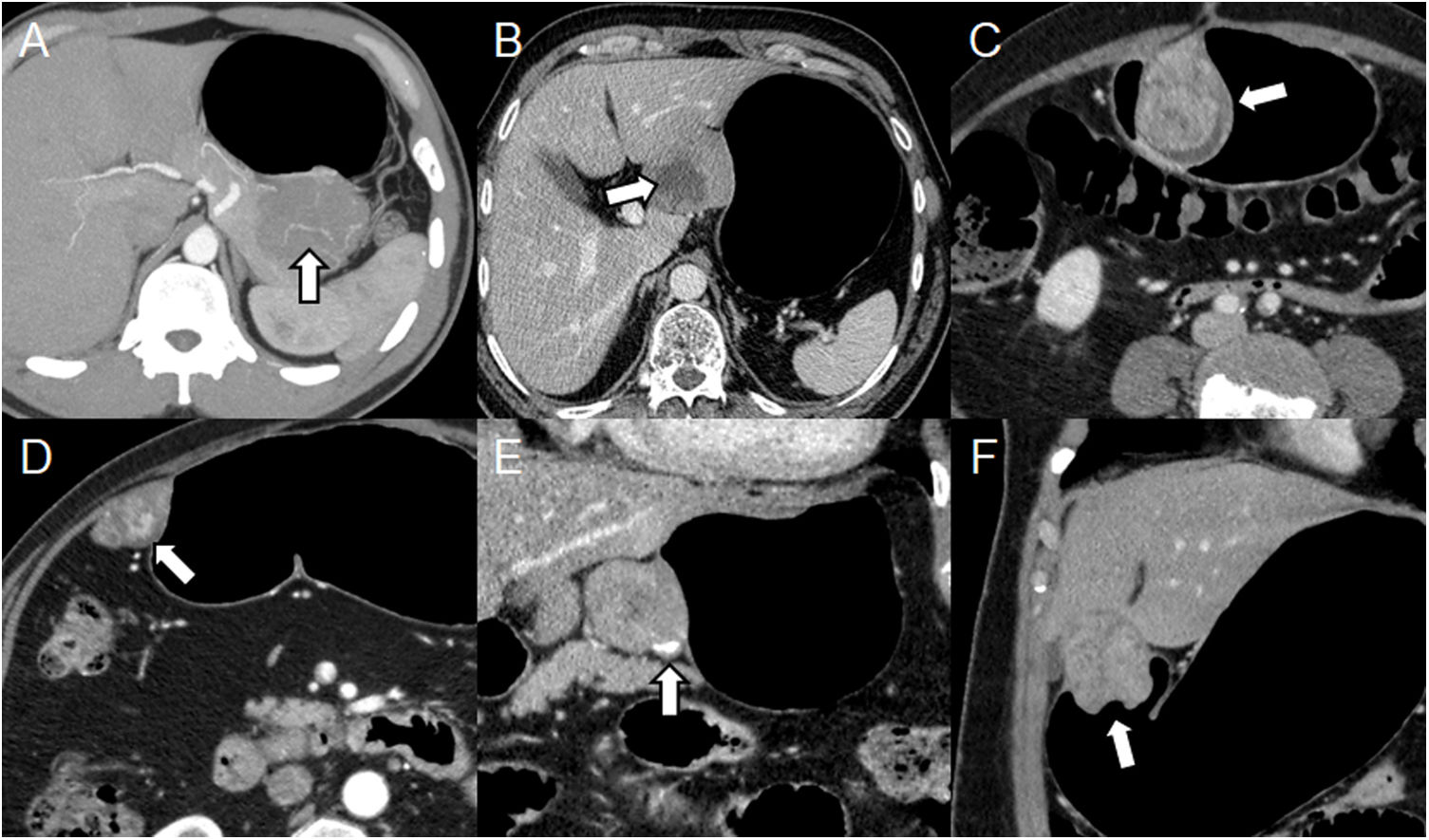

Other non-GIST sarcomasNon-GIST sarcomas include leiomyosarcomas, liposarcomas, and unclassified sarcomas, but are rare. They present as large masses with heterogeneous enhancement and areas of necrosis.3 Gastric leiomyosarcomas represent less than 1% of gastrointestinal malignancies.15 They may manifest as an exophytic, polypoid, ulcerative, or fungiform mass.16 The most common sites of metastasis are the liver and lungs (Fig. 3).17

Leiomyosarcoma in a 41-year-old woman with haematemesis, melaena, and anaemia. (A) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, a cross section shows an endoluminal mass with enhancement in the lesser curvature (arrow). (B) Pneumo-CT, coronal reconstruction with lung window reveals pulmonary metastases (black arrows). (C) Histology (×100; haematoxylin-eosin staining) shows intersecting clusters of spindle cells and greater cellularity than GIST. (D) Immunohistochemistry shows positivity for smooth muscle actin. The main differential diagnosis is GIST, being distinguishable by histology and immunohistochemistry, although a gastric location of leiomyosarcoma is extremely rare.

As their appearance is nonspecific, histological confirmation is necessary.3 Differential diagnosis with GIST is important because there is no consensus on the use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, with surgical resection being the treatment of choice.18

LeiomyomaThese are rare benign neoplasms and are the most common mesenchymal tumour of the oesophagus.13 They are usually located in the cardia and are indistinguishable from GISTs unless immunohistochemical techniques are employed. Leiomyomas are negative for CD117 and positive for desmin and smooth muscle actin.2 Histologically, they demonstrate hypocellular spindle cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm. The difference should be borne in mind because leiomyomas do not metastasize and GISTs are associated with malignant transformation and metastasis. Therefore, surgical resection is unnecessary unless obstruction or compression occurs.18

On MDCT, they manifest as a small homogeneous low-attenuation mass with an endoluminal growth pattern and little or moderate enhancement (Fig. 4).3,18 Tumours bigger than 2 cm may have a central ulceration.3

A 48-year-old male undergoing study due to abdominal pain, dyspepsia and heartburn. (A) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, curved coronal MPR reveals a low-attenuation homogeneous mass with an endoluminal growth pattern in the gastric cardia (arrow). Note the optimal gastric distension obtained in an area that is difficult for distension such as the gastroesophageal junction. (B) Histology (×100; haematoxylin-eosin staining) reveals low cellularity with intersecting fascicles of spindle cells. (C) Immunohistochemical analysis staining for smooth muscle actin, confirming the diagnosis of leiomyoma. The main differential diagnosis is GIST, which can only be distinguished by immunohistochemistry.

In summary, leiomyomas manifest as low-attenuation lesions in the gastric cardia.

LipomaLipomas are composed of adipose tissue surrounded by a fibrous capsule. They are usually small, endoluminal, located in the antrum and detected incidentally.19 Lesions bigger than 3 cm can ulcerate the mucosa and cause bleeding.20 Lipomas close to the pylorus can prolapse through it and cause obstruction.19

On MDCT they appear as a well-defined mass with an attenuation of −70 to −120 HU. (Fig. 5).19 It should be borne in mind that there may be mucosal ulceration or linear streaks of soft tissue attenuation due to inflammation.20 Resection is only indicated in symptomatic cases.3

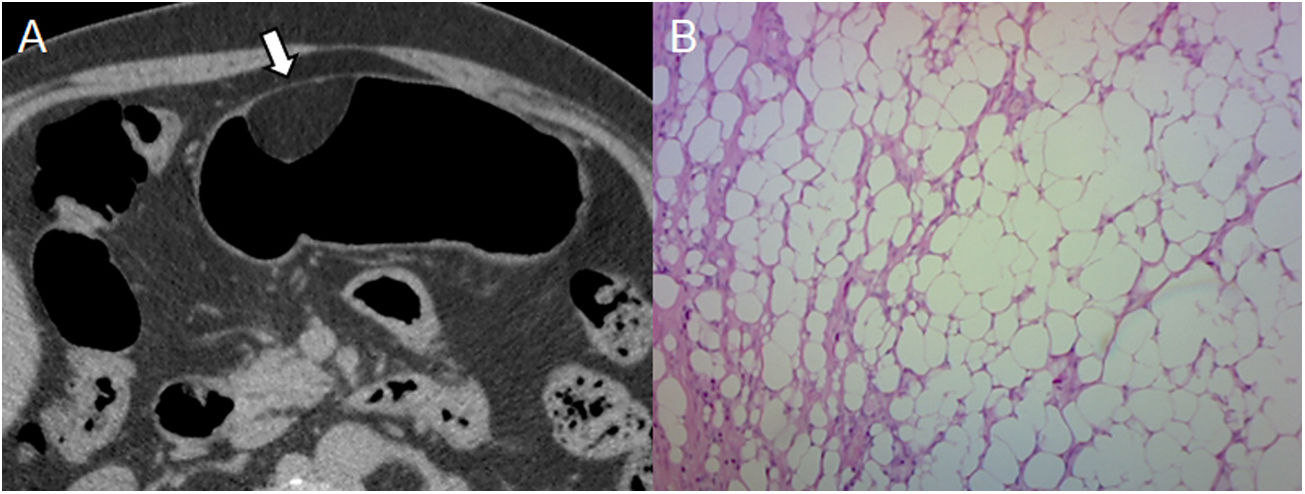

Lipoma found in a 60-year-old male during a routine endoscopy. (A) Pneumo-CT with contrast: axial section revealing a homogeneous lesion that sits on the greater curvature of the stomach with a negative density (arrow). (B) Histology (×100; haematoxylin-eosin staining) confirms the presence of mature adipose tissue. Adipose density is characteristic of lipoma and is diagnosed with CT, its main differential diagnosis being liposarcoma, which is extremely rare in the gastrointestinal tract and lymph node involvement or distant metastasis could indicate its diagnosis.

In summary, a well-circumscribed mass with attenuation between −70 and −120 HU is consistent with a lipoma.

Ectopic pancreasThis is a pancreatic tissue without a vascular or ductal connection to the main pancreatic body, usually located in the stomach, duodenum, or jejunum.

They are usually asymptomatic and discovered incidentally during surgery or autopsy; others manifest abdominal pain, bleeding, or obstruction.21 It should be borne in mind that ectopic pancreas can develop complications such as pancreatitis, pseudocysts, cystic dystrophy, insulinomas and malignant transformation.11

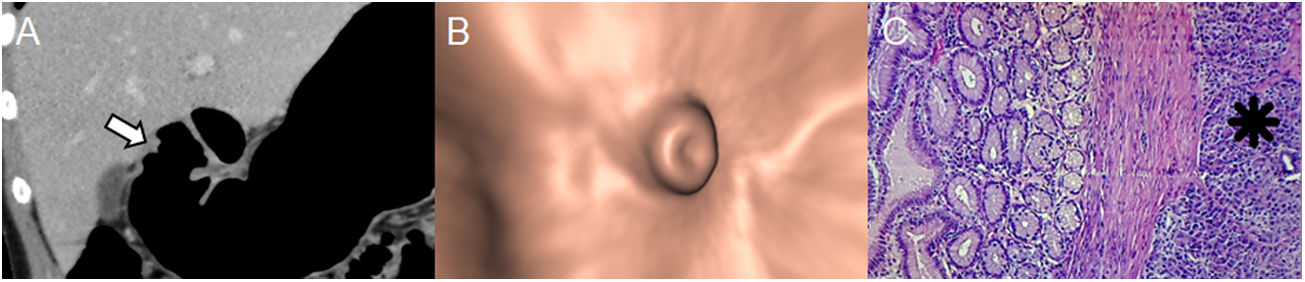

They are normally found in the prepyloric antrum as an intramural subepithelial nodule smaller than 3 cm, with a central umbilication that represents a rudimentary pancreatic duct and its orifice (Fig. 6).11 They may show an endoluminal growth pattern.21

Ectopic pancreas in an 18-year-old woman with haematemesis and melaena. (A) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, curved coronal MPR revealing an elevated lesion with central umbilication in the gastric antrum (arrow). Note the optimal gastric distension obtained in an area that is difficult for distension such as the pyloric region. (B) Virtual endoscopy better shows the central orifice of the rudimentary pancreatic duct. (C) Histology (×100; haematoxylin-eosin staining) shows the subepithelial glands separated by a fibrous stroma (asterisk). GISTs, neuronal and gastric carcinoid tumours are the main differential diagnoses (Figures 1, 7 and 8, respectively), sometimes representing a diagnostic challenge in which the enhancement of the overlying mucosa, the location, the growth pattern, the margins of the lesion and the correlation with endoscopic ultrasound must be considered.

On MDCT they show poorly defined borders and prominent mucosal enhancement similar to the pancreas. However, there is sometimes poor enhancement due to a minor component of pancreatic acini.22

Histologic findings include those of a normal pancreas: pancreatic acini, ducts, islets of Langerhans, and connective tissue.18

In summary, ectopic pancreas is located in the prepyloric antrum as an intramural nodule with endoluminal growth of under 3 cm, with a central umbilication.

Neurogenic tumoursThese constitute 5–10% of benign gastric tumours, the majority being nerve sheath tumours such as neurinomas, schwannomas and neuromas.23

Schwannomas arise from the myenteric plexus within the muscularis propria and are found primarily in the stomach (60–70 %), followed by the colon and rectum.24 Gastrointestinal schwannomas are distinctly different neoplasms from conventional soft tissue and central nervous system schwannomas due to different histological features, and they may also be associated with neurofibromatosis.24 In the gastrointestinal tract they show a prominent lymphoid cuff.18

Clinically, they are asymptomatic or present abdominal pain or gastrointestinal bleeding if there is mucosal ulceration. Large lesions can cause obstructive symptoms.25

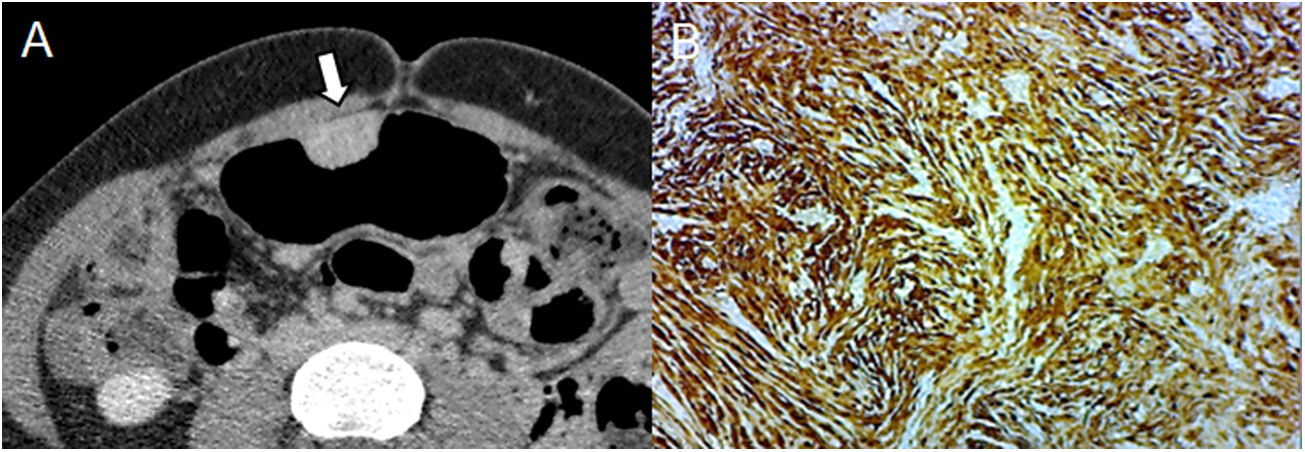

The characteristic feature on MDCT is homogeneous attenuation in phases with and without intravenous contrast, with delayed enhancement and an exophytic or intramural growth pattern (Fig. 7).3,18 Bleeding, necrosis, cystic degeneration, or calcification are rare.3

A 31-year-old woman undergoing study due to abdominal pain and dyspepsia. (A) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, cross section revealing an endoluminal mass with delayed enhancement during the equilibrium phase, which is characteristic of a schwannoma (arrow). (B) Immunohistochemical staining positive for S-100. The differential diagnosis includes GIST, leiomyoma, and lymphoma, with the absence of bleeding, necrosis, or cavitation being a characteristic in favour of a schwannoma.

Histological features consist of spindle cells with cuff-shaped peritumoral lymphocytic infiltration and occasional germinal centres.18 Immunohistochemistry shows positivity for S-100 protein.

In summary, schwannomas present homogeneous attenuation and delayed enhancement.

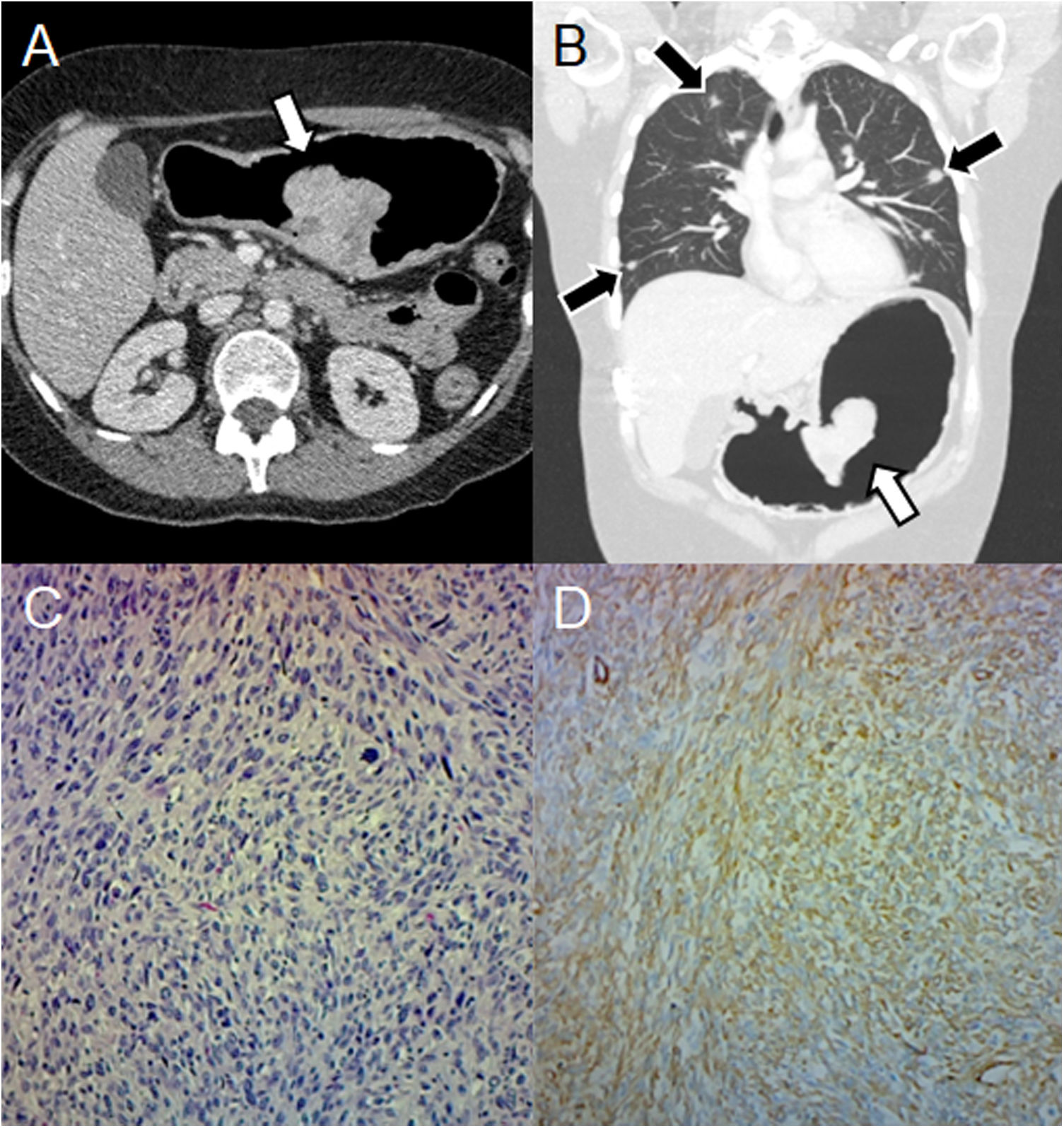

Neuroendocrine tumoursThese are well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumours originating from enterochromaffin cells located in the gastrointestinal tract, the pancreatobiliary tract, and the lung. Therefore, they are of epithelial origin, but since the bulk of the tumour is submucosal, they must be differentiated from other SELs.3 Carcinoid tumours represent 1.8% of gastric malignancies.26

They manifest as one or more small intraluminal SELs with avid enhancement in the arterial phase. Neuroendocrine carcinoma can appear as a large infiltrating ulcerated mass and the presence of metastasis and perigastric lymphadenopathy depends on tumour size (Fig. 8).11 The prognosis is poor, with a 20% survival rate at 5 years.3

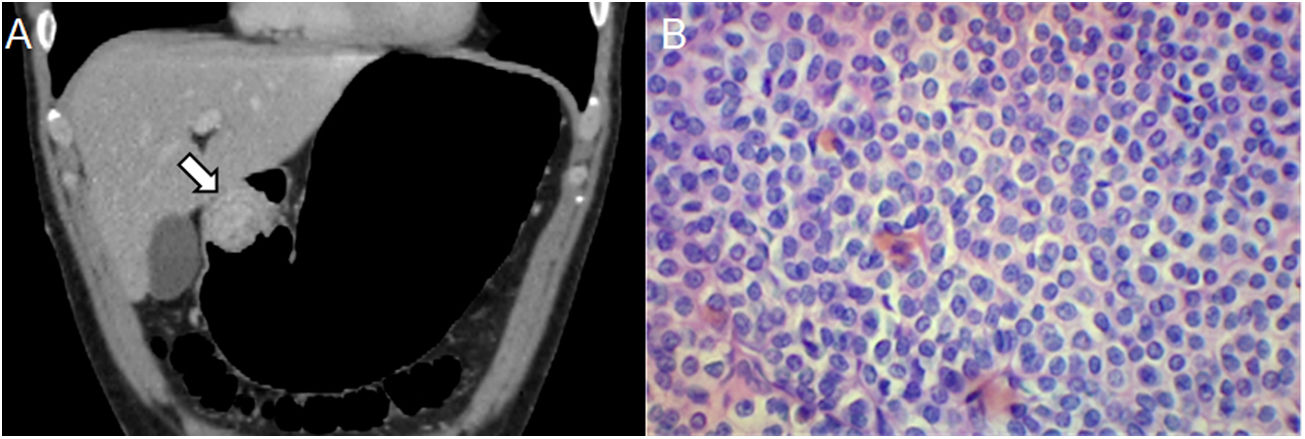

A 42-year-old man with an incidental finding of a gastric lesion on MDCT due to liver hemangioma. (A) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, coronal reconstruction revealing an endoluminal mass in the antropyloric region with heterogeneous enhancement (arrow). (B) Histology (×400; haematoxylin-eosin staining) shows neoplastic proliferation arranged in nests, a characteristic finding for neuroendocrine carcinoma. The differential diagnosis in multiple lesions includes polyps and metastases, and in a single lesion, adenocarcinoma, lymphoma and GIST, with histology being the method that defines the diagnosis.

Histological features show small, uniform cells arranged in nest patterns. High-grade carcinoid tumours may resemble small cell carcinomas, and these lesions are immunoreactive for chromogranin A and synaptophysin.18

In summary, carcinoid tumours manifest as a mass with avid arterial enhancement.

Inflammatory fibroid polypInflammatory fibroid polyps are rare non-neoplastic proliferating submucosal lesions characterised by a distinctive arrangement of fibrous tissue and blood vessels with an inflammatory infiltrate dominated by eosinophils.27 They are also known as Vanek's tumour, eosinophilic granuloma, submucosal fibroma, and inflammatory pseudotumour.

They are usually solitary and can develop anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract, but 75% appear in the antrum.3 They are usually asymptomatic or manifest abdominal pain or gastrointestinal bleeding. They do not demonstrate malignant potential.27

On MDCT, they appear as well-defined round or ovoid endoluminal masses with a slightly lobulated contour, measuring 2−5 cm, and may demonstrate ulceration and intense mucosal enhancement (Fig. 9).3,28 Enhancement can range from hyperattenuation to hypoattenuation caused by differences in histologic features.28

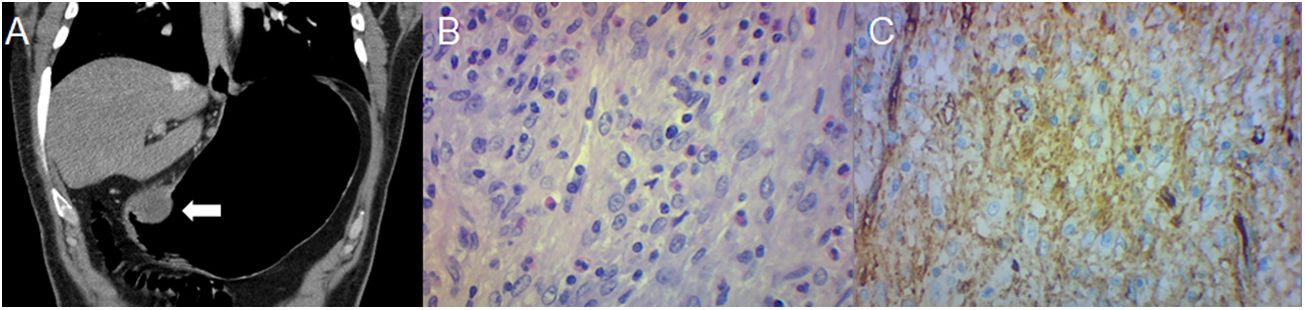

A 47-year-old man with abdominal pain and anaemia. (A) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, curved coronal MPR revealing an endoluminal mass in the gastric antrum (arrow). (B) Histology (×400; haematoxylin-eosin staining) shows spindle cells with an inflammatory component of lymphocytes and eosinophils. (C) Immunohistochemical analysis staining for CD34, confirming the diagnosis of inflammatory fibroid polyp. Diagnosis using CT alone is considered difficult, and the differential diagnosis includes adenomatous polyps, endoluminal GISTs, carcinoid tumours, and schwannomas.

In summary, inflammatory fibroid polyps arise as a polypoid mass in the antrum with variable enhancement.

MetastasisGastric metastasis occurs by direct extension of a malignant primary peritoneal carcinomatosis with serous implants and as embolic metastasis with intramural SEL.11 They are classified as hypervascular or hypovascular. It should be borne in mind that hypervascular metastases include malignant melanoma and breast cancer, and less commonly renal cell carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, neuroendocrine carcinoma, and mesenchymal sarcoma, and the most common hypovascular metastases are of pulmonary or oesophageal origin.29

Metastatic melanomas manifest as isolated or multiple small intramural nodules and polypoid masses with or without ulceration (Fig. 10).30 Large lesions may demonstrate necrosis, bleeding, or degenerative changes.

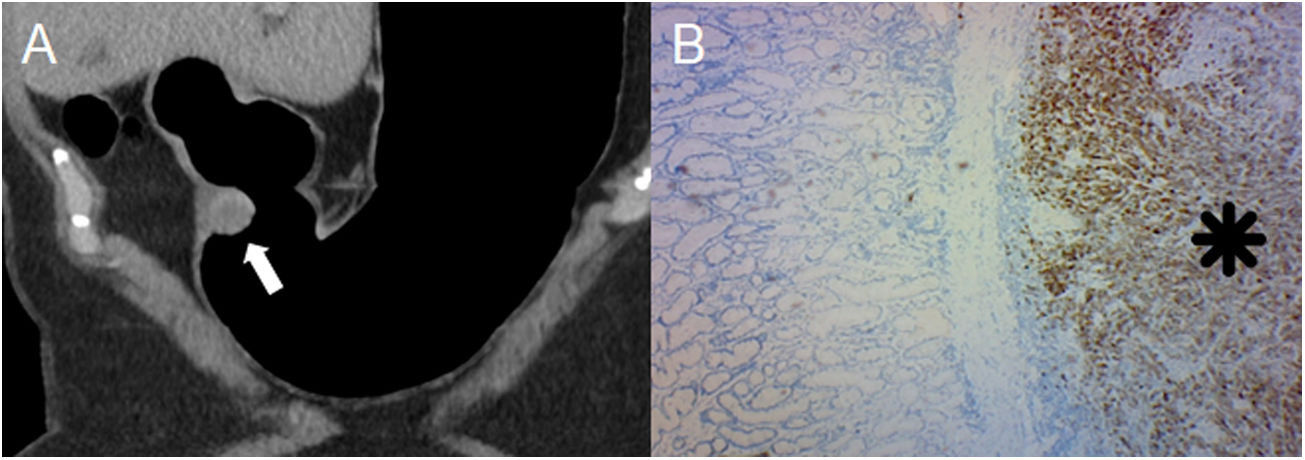

72-year-old woman with a history of melanoma under study for anaemia. (A) Pneumo-CT with intravenous contrast, curved coronal MPR revealing an endoluminal mass in the antropyloric region with peripheral enhancement in the arterial phase (arrow). (B) Positive immunohistochemistry for MELAN-A (asterisk) confirming the presence of melanoma metastases. Differentiating gastric metastases from other lesions is difficult, and it is important to understand the history of the primary tumour and its characteristics on CT to help make a more accurate diagnosis.

In summary, the characteristics of the primary tumour define the behaviour of the metastases.

ConclusionsPneumo-CT combined with multiplanar, three-dimensional reconstructions and virtual endoscopy can be considered a useful and non-invasive technique for the characterisation of these lesions due to the additional GD.

FundingThis study received no specific grants from public agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

AuthorshipResponsible for the integrity of the study: RLG, LS and MU.

Study conception: RLG and LS.

Study design: RLG, EG and MU.

Data acquisition: RLG, EG and JPS.

Data analysis and interpretation: RLG, EG and LS.

Statistical processing: N/A.

Literature search: RLG, EG and JPS.

Drafting of the article: RLG, EG, LS, JPS and MU.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: LS, JPS and MU.

Approval of the final version: RLG, EG, LS, JPS and MU.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: López Grove R, Gentile E, Savluk L, Santino JP, Ulla M, Correlación anatomopatológica con neumo-tomografía computarizada de lesiones gástricas subepiteliales, Radiología. 2022;64:237–244.