Supplement “Pulmonary Interstitial Pathology”

More infoThe term cystic lung disease encompasses a heterogeneous group of entities characterised by round lung lesions that correspond to cysts with fine walls, which usually contain air. The differential diagnosis of these lesions can be challenging, requiring both clinical and radiological perspectives. Entities such as pulmonary emphysema and cystic bronchiectasis can simulate cystic disease.

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) is the imaging technique of choice for the evaluation and diagnosis of cystic lung disease, because it confirms the presence of lung disease and establishes the correct diagnosis of the associated complications. In many cases, the diagnosis can be established based on the HRCT findings, thus making histologic confirmation unnecessary. For these reasons, radiologists need to be familiar with the different presentations of these entities.

A wide variety of diseases are characterised by the presence of diffuse pulmonary cysts. Among these, the most common are lymphangioleiomyomatosis, which may or may not be associated with tuberous sclerosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, and lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia. Other, less common entities include Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome, amyloidosis, and light-chain deposit disease.

This article describes the characteristics and presentations of some of these entities, emphasizing the details that can help differentiate among them.

Las enfermedades quísticas pulmonares engloban a un grupo heterogéneo de entidades, caracterizadas por la presencia de quistes, correspondientes a lesiones pulmonares redondeadas de contenido usualmente aéreo y de pared fina. Su diagnóstico diferencial constituye un reto, que debe de ser manejado desde una perspectiva clínica y también radiológica. Entidades como el enfisema pulmonar y las bronquiectasias quísticas pueden simular enfermedades quísticas.

La tomografía computarizada de alta resolución es el método de imagen de elección en la evaluación y el diagnóstico de las enfermedades quísticas pulmonares, ya que confirma la presencia de enfermedad pulmonar y establece el correcto diagnóstico de las complicaciones asociadas. En muchos casos, el diagnóstico se establecerá preferentemente con base en los hallazgos presentes en esta técnica de imagen, obviando la necesidad de una comprobación anatomopatológica. Por estas razones, el radiólogo debe familiarizarse con las diferentes presentaciones de estas entidades.

Una amplia variedad de enfermedades se caracteriza por la presencia de quistes pulmonares difusos. Entre ellas, las más frecuentes son las linfangioleiomiomatosis, asociadas o no a esclerosis tuberosa, la histiocitosis de células de Langerhans y la neumonía intersticial linfoide. Otras entidades menos frecuentes son el síndrome de Birt-Hogg-Dubé, la amiloidosis y la enfermedad por depósito de cadenas ligeras.

En este artículo se describen las características y las formas de presentación de algunas de estas entidades, haciendo hincapié en los detalles diferenciales de las mismas.

Cystic lung diseases are rare and are characterised on computed tomography (CT) by the presence of cysts, defined as round lesions with low attenuation, air content (occasionally liquid or solid), a thin wall (<3mm) consisting of epithelial tissue or fibrosis, and that are clearly demarcated by adjacent normal lung.1 It is important to distinguish them from other more common lung lesions containing air2–4:

- 1.

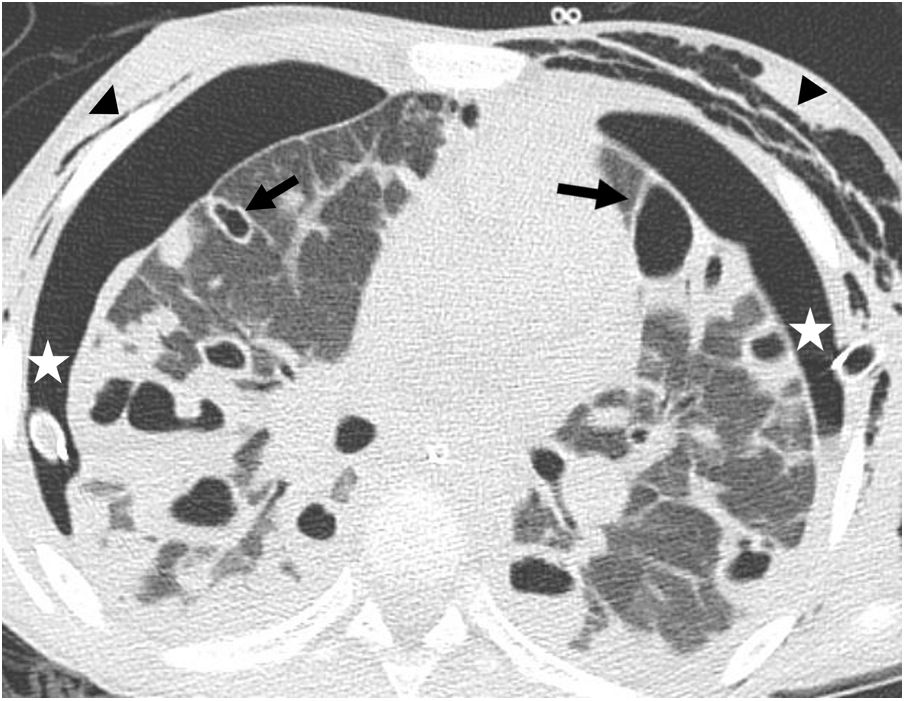

Cavities: they appear within consolidations, masses or nodules and have a thicker wall (>4mm) than that of cysts (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.Nine-year-old female patient with Staphylococcus aureus pneumonia. The CT image reveals multiple air-filled cavitation foci within bilateral pulmonary nodules, with a predominantly subpleural distribution, and in areas of right lower lobe consolidation. In addition, bilateral thin-walled cysts corresponding to pneumatoceles can be seen (black arrows). Bilateral pneumothorax is observed, presumably due to rupture of one of the peripheral cavitated lesions, with pleural drainage tubes in both hemithoraces (asterisks). Bilateral subcutaneous emphysema is also identified (arrowheads).

(0.11MB). - 2.

Centriacinar emphysema: areas of decreased attenuation, without a wall, of up to 1cm. Sometimes a thin wall is observed, which is included in the differential diagnosis of cystic lung diseases, but the predominant location in the upper fields, a history of smoking and the frequent identification of a central point that corresponds to the centrilobular artery aid in the diagnosis. (Fig. 2)

Figure 2.Centriacinar and distal acinar emphysema in a male patient who smokes. The HRCT image of the upper lobes reveals multiple areas of decreased attenuation without a discernible wall, corresponding to centriacinar emphysema. The presence of the centrilobular arteriole inside them stands out in some of them (arrows). Distal acinar emphysema with subpleural bullae is also seen, especially in the right upper lobe (thick arrow).

(0.09MB). - 3.

Distal acinar emphysema and bullae: distal acinar emphysema manifests as subpleural or peribronchovascular areas of low attenuation up to 1cm in diameter, delimited by the pleura or septa, without a true wall as with cysts. The bullae are due to the confluence of areas of distal acinar emphysema and are lesions >1cm, predominantly subpleural and with an almost imperceptible wall (Fig. 2).

- 4.

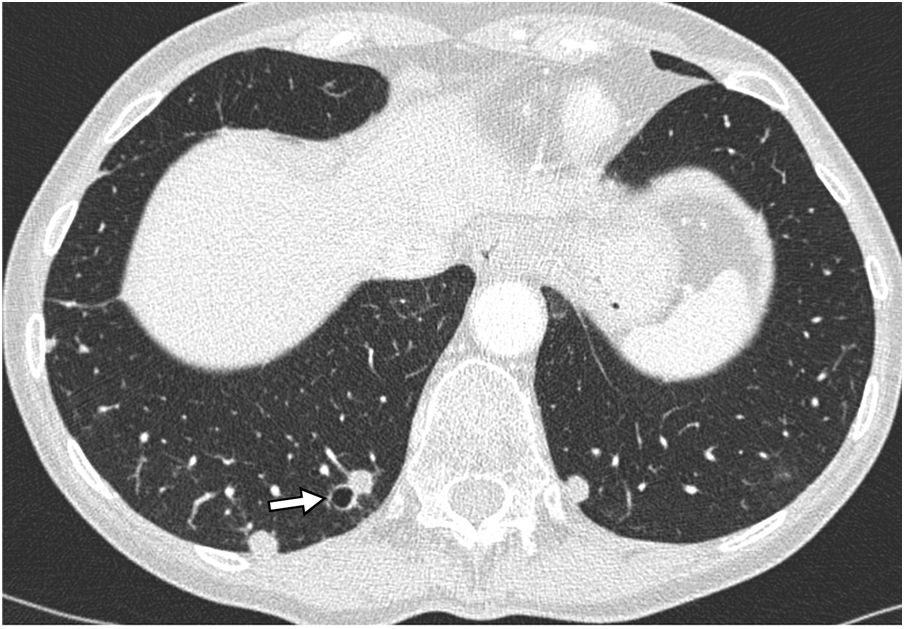

Cystic bronchiectasis: careful review of contiguous axial slices or coronal or sagittal reconstructions help to identify its tubular appearance. It can be accompanied by a thickening of the bronchial wall, air trapping and nodules with a tree-in-bud distribution (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.Superinfected cystic bronchiectasis. The HRCT image of the lower lobes reveals multiple bilateral cystic images, some of them with an air-fluid level (arrow), corresponding to cystic bronchiectasis. The presence of nodules with a tree-in-bud distribution is also observed, corresponding to bronchiolar impactions (circle).

(0.14MB). - 5.

Pneumatoceles: rounded thin-walled air spaces secondary to pneumonia, trauma, or hydrocarbon aspiration, usually few in number and transient, resolving in weeks or months (Fig. 1).

- 6.

Honeycomb cysts are air-filled cystic lesions with a usually uniform size (3−10mm, occasionally larger), with a well-defined 1−3mm wall grouped so that they share a wall. In advanced stages they are arranged in layers, typically in the subpleural region. They are considered specific for pulmonary fibrosis and are associated with other signs such as volume loss, a reticular pattern, and traction bronchiectasis (Fig. 4).

Table 1 lists the main diseases associated with lung cysts. For the differential diagnosis of cystic lung diseases, it is essential to analyse the cysts' size, number, morphology and distribution, together with other possible associated imaging findings, such as ground-glass opacities or nodules (Table 2). Sometimes the CT findings and the clinical context will enable a specific diagnosis, and other times a biopsy will be necessary.3–6

Causes of diffuse cystic lung diseases.

| Main causes |

| Lymphangioleiomyomatosis |

| Pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis |

| Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome |

| Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia |

| Amyloidosis |

| Other causes |

| Hypersensitivity pneumonitis |

| Desquamative interstitial pneumonia |

| Associated with ageing (ageing lung cysts) |

| Light-chain deposition disease |

| Hereditary syndromes: Neurofibromatosis type 1, Proteus syndrome, Ehler-Danlos syndrome |

| Congenital pulmonary airway malformation |

| Metastasis |

| Infections |

| Advanced fibrosis (IPF, sarcoidosis, etc.) |

Differential diagnosis of the main diffuse cystic lung diseases on CT.

| Disease | Cyst wall | Cyst morphology | Distribution | Associated findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAM | Fine | Rounded | Diffuse | Pneumothorax, pleural effusion, lymphangiomas, renal angiomyolipomas, ascites |

| LCH | Fine/thick | Rounded, irregular, or "odd" shaped | Predominance in the upper fields, costophrenic angles preserved | Pulmonary nodules, some cavitated |

| BHD | Fine | Round, oval, lenticular, septated | Basal predominance; subpleural, paramediastinal, juxtacissural distribution | Pneumothorax. Renal tumours |

| LIP | Fine | Rounded | Diffuse or in lower fields; peribronchovascular, subpleural | Ground-glass, centrilobular nodules, septal thickening and peribronchovascular interstitium; lymphadenopathies |

| Amyloidosis | Fine | Rounded. Sometimes calcified nodules on their wall or inside | Diffuse, peribronchovascular, or subpleural | Multiple nodules, often calcified |

BHD: Birt-Hogg-Dubé; LCH: pulmonary Langerhans cell histiocytosis; LAM: lymphangioleiomyomatosis; LIP: lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia.

The main hypothesised mechanisms to explain the development of lung cysts are: 1) partial bronchiolar obstruction with a valvular mechanism: infiltration of the bronchiolar walls (by lymphocytic infiltrate in lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP), by smooth muscle cells in lymphangioleiomyomatosis, by Langerhans cells in pulmonary histiocytosis, or by amyloid) would cause more distal dilatation/air trapping 7–12; 2) focal pulmonary ischaemic necrosis, such as that due to vascular amyloid deposition with secondary reduction in blood flow3,11,13,14; 3) destruction of the bronchial or alveolar walls, as occurs in pulmonary histiocytosis due to infiltration of the bronchial wall by Langerhans cell granulomas, or due to infiltration of the alveolar walls by lymphoplasmacytic cells in Sjögren's syndrome15,16; 4) action of proteolytic enzymes (metalloproteinases) that degrade the extracellular matrix and elastic membranes of the airways, and have been associated with the development of lung cysts in Langerhans cell histiocytosis, lymphangioleiomyomatosis, and light-chain deposition disease of the lung3,11,13,17 and 5) retractile fibrosis with dilated airspaces, as occurs in the fibrotic phase of Langerhans cell histiocytosis.5,6,15

Main diffuse cystic lung diseasesLymphangioleiomyomatosisLymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) is a rare systemic disease characterised by infiltration of the lung parenchyma by abnormal smooth muscle cells, leading to its destruction by forming diffuse lung cysts. It is considered a low-grade metastasising neoplasm, but the origin of these abnormal cells, which reach the lungs via the lymphatic system or the blood, is unknown. Mutations in the TSC1 or TSC2 genes, which encode the hamartin and tuberin proteins, are implicated in its pathogenesis. The abnormality of these results in activating the mTOR pathway and secondarily in uncontrolled cell proliferation, angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. There are sporadic forms of LAM (TSC2 mutations in somatic cells) and autosomal dominantly inherited forms associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), which is characterised by developmental delay, seizures, skin lesions, and benign tumours in multiple organs, with TSC1 and TSC2 mutations in the germ line. Around 30% of women and 10% of men with TSC have LAM. Renal angiomyolipomas are present in almost all patients with LAM associated with TSC and in 30–40% of sporadic cases (Fig. 5), and other lymphatic abnormalities may be seen, such as lymphadenopathies, lymphangioleiomyomas, dilatation or occlusion of the thoracic duct, chylothorax or chylous ascites.18,19

The sporadic forms are exclusive to women, and although cystic lung disease may be seen in 10% of men with tuberous sclerosis, symptomatic lung disease occurs almost exclusively in women of childbearing age. The abnormal cells express oestrogen receptors, which explains the rapid decline in lung function in premenopausal women, with oestrogen use, and during pregnancy. LAM is slowly progressive: 10 years after diagnosis, half of the patients experience dyspnoea with daily activities, 20% require oxygen, and 10% have died. Median survival is more than 20 years after diagnosis.18,19

A dilatation of the distal airspaces due to the valvular effect, secondary to stenosis of the terminal bronchioles infiltrated by abnormal muscle cells, has been hypothesised as the mechanism of cyst formation.5 Another possible mechanism involves metalloproteinases, overexpressed in LAM cells, which would alter the extracellular matrix.20,21 Infiltration by LAM cells also leads to the destruction of the arteriolar wall and occlusion of pulmonary arterioles.5

The most common forms of presentation of LAM are recurrent pneumothorax in women of childbearing age and progressive dyspnoea, with an obstructive spirometry pattern and restricted diffusing capacity. Chylothorax is the initial manifestation in 20% of cases. Other atypical presentations may be abdominal, secondary to bleeding from renal angiomyolipomas, growth of lymphangioleiomyomas, or chylous ascites. Increasingly commonly, the disease is detected incidentally in imaging tests performed for another reason, or it may be found in screening for tuberous sclerosis.

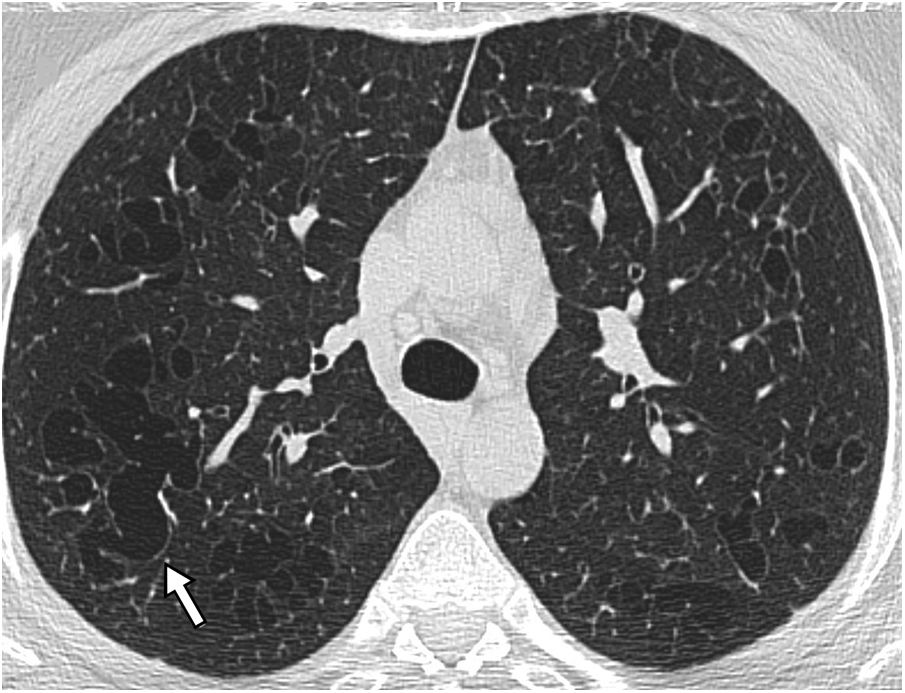

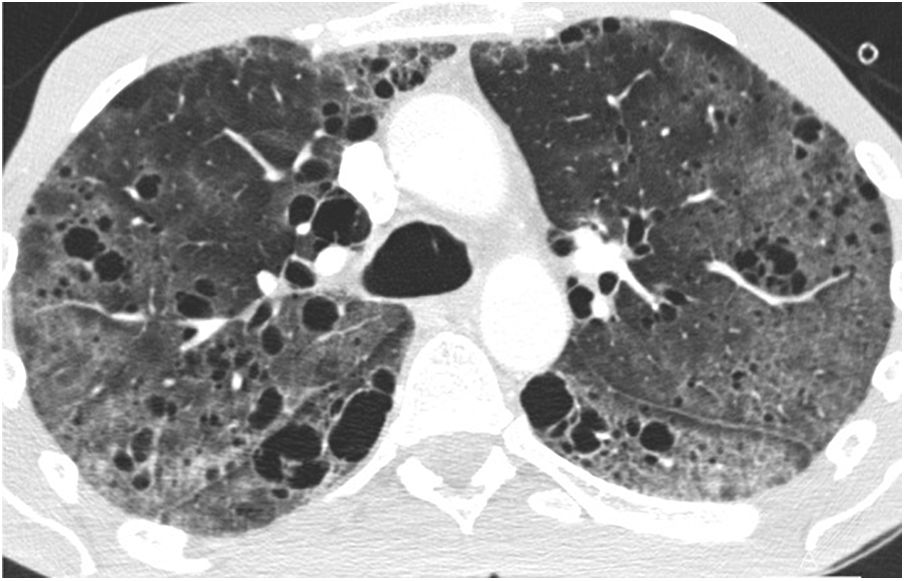

Chest radiograph in the initial phases is usually normal, and as the disease progresses, an increase in lung volume can be seen with reticular or nodular involvement. Other findings include lymphadenopathy, effusion, or pleural thickening. CT is the essential imaging test for diagnosing LAM and is recommended for LAM screening in women of childbearing age with the first episode of pneumothorax, in all women with recurrent pneumothorax, and patients with tuberous sclerosis older than 18 years.22–24 The main finding on CT is thin-walled air cysts that are diffusely distributed, ranging in size from a few millimetres to several centimetres, and rounded, although more atypically shaped when they grow and coalesce.13,14,25,26 In the initial phases, the cysts are few and increase in number and size so that in the advanced phases, little normal parenchyma remains between them (Figs. 5 and 6). Vessels can be seen on the periphery of the cysts but not in their centre, which helps to differentiate them from centriacinar emphysema. The presence of cysts in the costophrenic angles, their absence in the apical regions and the lack of nodules are useful data for the differential diagnosis of Langerhans cell histiocytosis. As isolated lung cysts may be seen as the result of normal ageing,27 a minimum of four cysts are required to be considered pathological (and four to 10 to diagnose LAM in patients with tuberous sclerosis).18 Other infrequent findings are ground-glass opacities (due to proliferation of smooth muscle cells, alveolar haemorrhage or accumulation of lymphatic fluid), septal thickening (due to lymphatic infiltration), or centrilobular nodules (due to infiltration by smooth muscle cells forming macroscopic nodules or multifocal hyperplasia).18,28 Lymphadenopathy, pleural or pericardial effusion, dilatation of the thoracic duct, pneumothorax (Fig. 6) and cystic lymphangioleiomyomas may also be seen.

Lymphangioleiomyomatosis in a 38-year-old woman The image reconstruction in the coronal plane shows extensive bilateral pulmonary cystic involvement, with a slight predominance in the middle and lower lung fields. Note the presence of a small right apical pneumothorax (arrow) and a small amount of subcutaneous emphysema on the right lateral chest wall.

CT may be sufficient to establish the diagnosis of LAM in an appropriate clinical context (tuberous sclerosis, renal angiomyolipomas, lymphangiomas, chylothorax, chylous ascites, etc.). The most recent clinical guidelines support the use of serum levels of lymphangiogenic growth factor VEGF-D >800pg/mL to establish the diagnosis in women with a compatible CT, without the need for a biopsy.29,30 Pathological confirmation is reserved for cases with severe lung involvement before starting treatment with mTORC1 inhibitors (sirolimus, everolimus), which improve lung function. Lung transplantation is considered for patients with very advanced disease, although recurrence of the disease in the transplanted lung has been described.

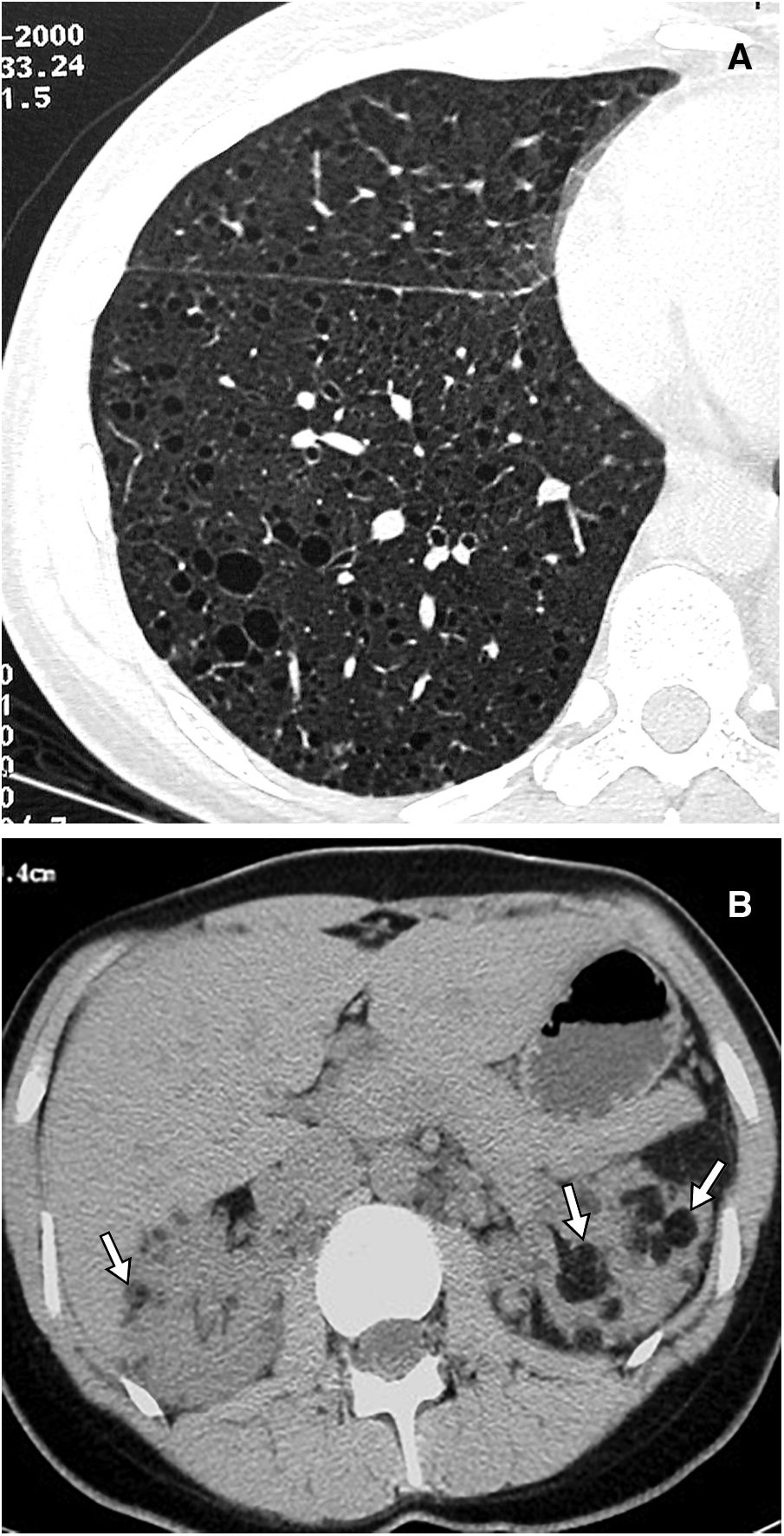

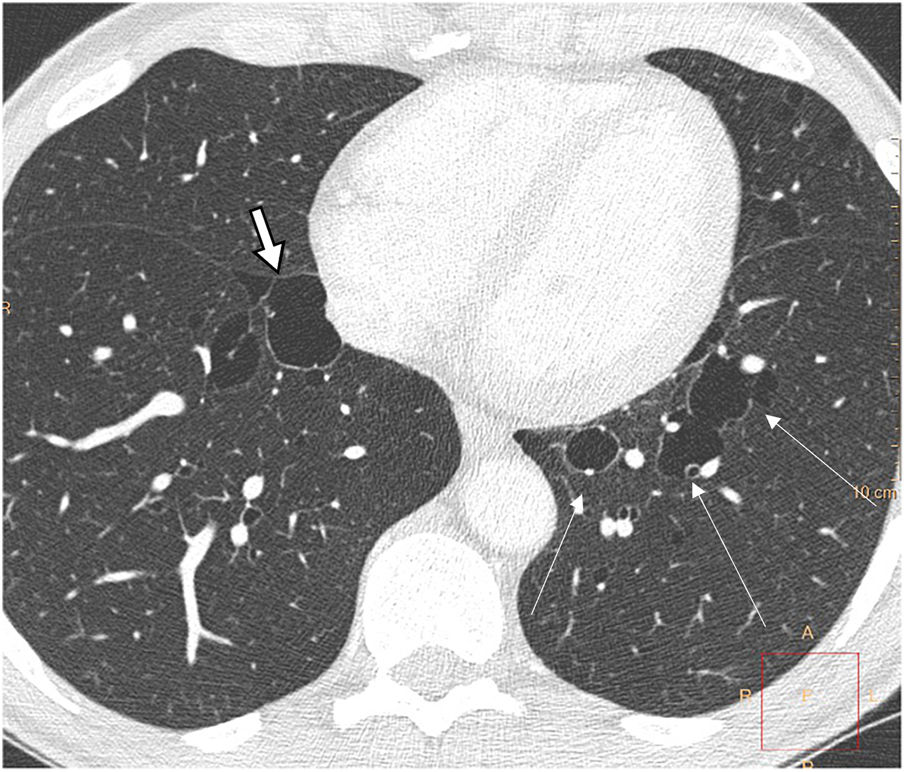

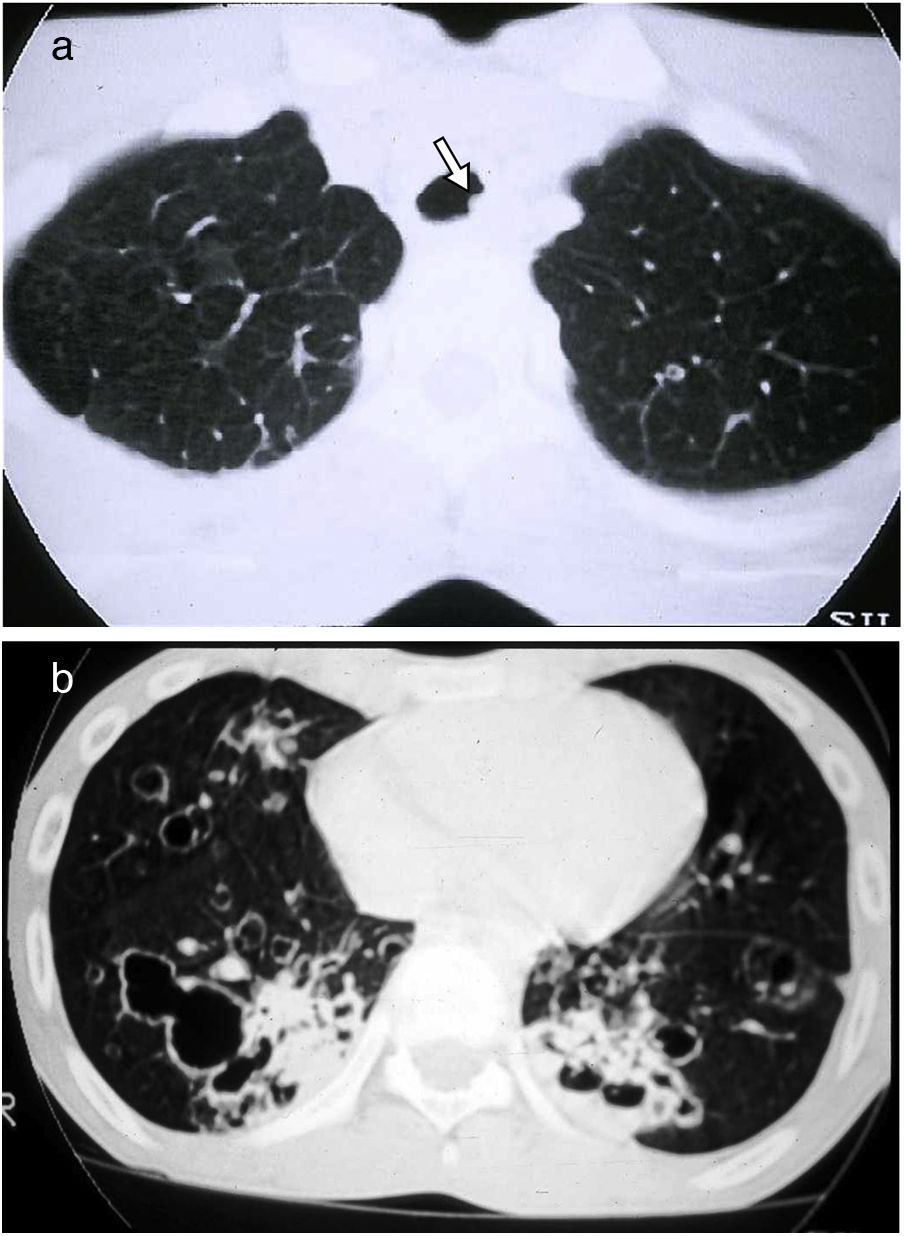

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH)LCH is a rare tobacco-related interstitial lung disease diagnosed in young adults with a current or previous history of smoking. Components of tobacco smoke are thought to activate pulmonary Langerhans cells, which, along with other inflammatory cells, accumulate to form peribronchial infiltrates and granulomas that result in stellate nodules. These nodules may show cavities that correspond to bronchiolar dilatation. In the most advanced stages, peribronchial fibrosis pulls and dilates the contiguous air spaces.14 The most common symptoms are dyspnoea and cough, but there are often no respiratory symptoms. Some patients start with pneumothorax (15%), and a small percentage have systemic symptoms, pain secondary to bone involvement, cutaneous eruptions, or diabetes insipidus. Chest radiographs may reveal upper lobe nodules in the initial phases, and later reticular and cystic abnormalities, with preserved or increased lung volumes. On CT in the initial phases, peribronchiolar centrilobular nodules predominate, measuring 1−5mm, which are poorly defined or irregular, with bilateral and symmetrical distribution, predominantly in the upper and middle lung fields, with the costophrenic angles and the internal part of the middle lobe and the lingula preserved. As the disease progresses, cavitated nodules appear (Fig. 7) with thick walls and, later on, thin-walled cysts of different sizes, generally less than 1cm. However, they may coalesce in advanced stages, and large cysts with irregular or atypical (lobulated, branched, etc.) morphology are seen. (Fig. 8) Both pathologically and on CT, there is temporal heterogeneity, and cavitated nodules may coexist with thick- and thin-walled cysts.2,5,6,12 The hypothesised mechanism of cyst formation is dilatation of the bronchioles secondary to chronic inflammation with destruction of their walls.15 In the more advanced stages there is fibrotic scarring and peribronchiolar paracicatricial emphysema. The disease may return spontaneously or after smoking cessation in 25% of patients, stabilise in 50%, or progress to diffuse destructive cystic disease in 25% with respiratory failure, even after smoking cessation. Pulmonary hypertension is a complication associated with higher mortality and is usually more serious than that related to other causes, such as emphysema or pulmonary fibrosis.31 Its prevalence is high, around 40% in a recent series,32 so screening with echocardiography is indicated. In patients with long-standing disease and significant cystic involvement of the lungs, mimicking extensive emphysema, the existence of signs of pulmonary hypertension may guide us towards diagnosing LCH. It is not possible to determine with CT the subgroup of patients with LCH that will progress, so follow-up with respiratory function tests is important. Lung transplantation is an option in cases of advanced disease.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis. (A) The HRCT image centred on the upper lobes shows multiple subcentimetre nodules with irregular contours, some cavitated (white arrows) and also air-filled cystic images (black arrow). (B) The image reconstruction in the coronal plane highlights the predominant distribution in the upper lung fields, with preservation of the lung bases.

Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome is a rare multisystemic disease transmitted by autosomal dominant inheritance caused by a germline mutation of the folliculin gene. This mutation can be inherited or appear de novo in patients with no family history. It is manifested by skin lesions (fibrofolliculomas), multiple lung cysts, spontaneous pneumothoraxes, and renal tumours, which are often multifocal, bilateral, and slow-growing, with a predominance of oncocytomas and chromophobe neoplasms. There is marked phenotypic variability: from asymptomatic carriers to varying degrees of lung, cutaneous, and renal involvement. Its prevalence is estimated at 1 in 200,000, but its exact incidence is unknown. It affects any age group without gender predilection, although it predominates in people in their 20s or 30s.33

Lung cysts appear in 80% of patients, in youth or middle age. On CT, the cysts are thin-walled, preferentially located in the lung bases, with subpleural peripheral distribution, including paramediastinal and perifissural location, and also about interlobular septa, arteries, and veins (Fig. 9). They can be round, but also irregular, elliptical and lenticular, and the largest, septated. The presence of elliptic and paramediastinal cysts is especially indicative of this entity and useful for differential diagnosis with other cystic lung diseases. The cysts are larger and fewer in number than in LAM and, unlike in LAM, their number and size do not seem to increase progressively.33–38 Microscopically they are lined with pneumocytes and partially surrounded by septal or pleural interstitial tissue.33,34

The roles played by abnormalities in the mTOR pathway and metalloproteinases have been hypothesised in the mechanism of cyst formation,33,34 which would lead to lung matrix abnormalities, deficient adhesion between cells and expansion of alveolar spaces as a consequence of stress induced by stretching in breathing.

Most patients with lung cysts are asymptomatic, except in episodes of pneumothorax. Unlike LAM and histiocytosis, they do not experience progressive deterioration of respiratory function. The most important aspects in the management of these patients are pleurodesis after the first episode of spontaneous pneumothorax, due to the high incidence of recurrence of pneumothorax,39 and follow-up for early detection of renal tumours. Family members should be screened for the disease.

Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonia (LIP)/follicular bronchiolitisLIP is a benign lymphoproliferative disorder, characterised by pulmonary interstitial infiltration by polyclonal lymphocytes, plasma cells, and histiocytes, predominantly in the perilymphatic interstitium (alveolar septal, interlobular, peribronchovascular, and subpleural).40–43 It is included in the list of idiopathic interstitial diseases, although it is often secondary to other diseases. Follicular bronchiolitis (FB) is characterised by follicular lymphoid hyperplasia in the walls of bronchioles and blood vessels, although in some cases the cellular infiltrate extends to the alveolar septa in a focal, non-diffuse manner as in LIP, which suggests that these entities are part of the same spectrum of disease.11,14 Both LIP and FB are associated with Sjögren's syndrome and other collagen diseases (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus), various autoimmune disorders, dysproteinaemias (hypergammaglobulinaemia, hypogammaglobulinaemia, common variable immunodeficiency), human immunodeficiency virus infection (above all in children) and other viruses.40–43

LIP affects middle-aged patients, with a predominance of women, and is usually manifested by cough and dyspnoea that progress over months or years, occasionally with associated systemic symptoms (fever, night sweats, weight loss, arthralgia). In respiratory function tests there is a restrictive pattern with reduced diffusing capacity.

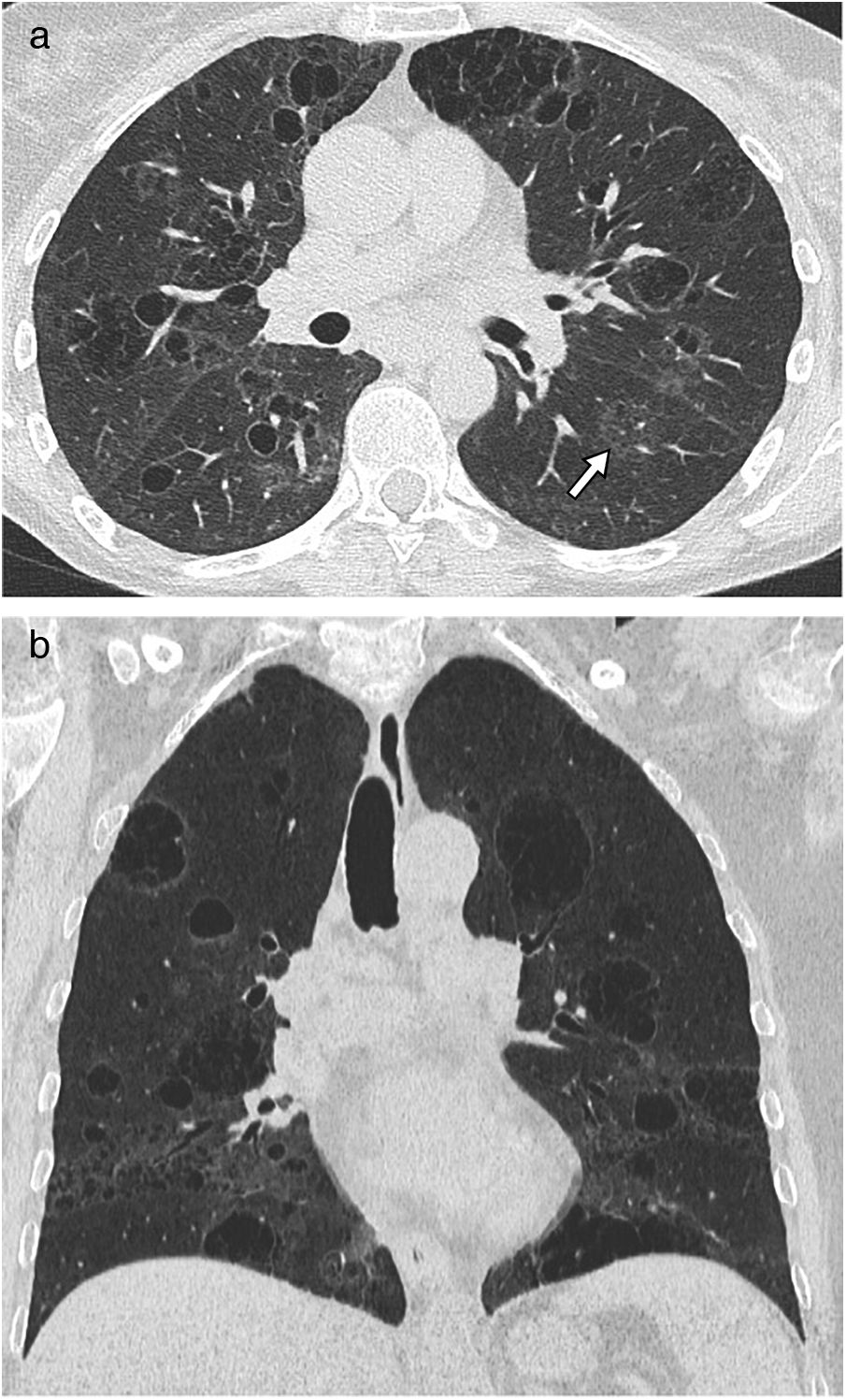

Reticulonodular infiltrates are seen on chest radiographs, and as they progress, ground-glass opacities and consolidations may appear. The main findings on CT are ground-glass opacities, centrilobular nodules and air cysts, which are present in up to 80% of cases (Fig. 10). Subpleural nodules, septal and peribronchovascular thickening, and lymphadenopathy may also be seen. Air cysts are few in number, usually less than 3cm, are frequently seen in ground-glass areas, and are random in distribution, although they are often seen adjacent to a vessel or bronchus and can also be subpleural.44,45 On follow-up CT, nodules and ground-glass opacities may disappear, but cysts may persist.46 Partial airway obstruction secondary to peribronchiolar lymphocytic infiltration with distal air trapping has been hypothesised as a pathogenic mechanism of these cysts. There may also be ischaemia due to vascular obstruction.9,11,40,43–45 Identification of these cysts is useful for the differential diagnosis with cellular NSIP and lymphoma, but can be difficult both with CT and pathology.40,42,43,47 In patients with LIP associated with Sjögren’s disease, the appearance of large nodules should lead to suspicion of amyloidosis—especially if the nodules are calcified—or lymphoma.10,40 (Fig. 11) On CT, hypersensitivity pneumonitis can present very similar findings to those of LIP, with cysts in up to 13% of cases.8 Differentiation can also be difficult for the pathologist, but usually the clinical context helps with the differential diagnosis.

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) in a 65-year-old woman with Sjögren's syndrome. (A) The HRCT image at the level of the pulmonary hila demonstrates multiple thin-walled air-filled cystic images. Also note the presence of ground glass opacities (arrow). (B) The image reconstruction in the coronal plane reveals the diffuse distribution of the findings.

Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP) associated with pulmonary MALT lymphoma in a 60-year-old woman with Sjögren's syndrome. The HRCT image reveals pulmonary cysts and bilateral pulmonary nodules with irregular borders and an air bronchogram inside (arrow), corresponding to lymphoma foci.

The natural evolution and prognosis are variable: they can resolve spontaneously, improve or stabilise with corticosteroids, or progress to respiratory failure and pulmonary fibrosis with the appearance of honeycombing on CT despite corticosteroid treatment.40,46 Five percent of patients develop lymphoma over the course of evolution. About 30–50% of patients die within five years.

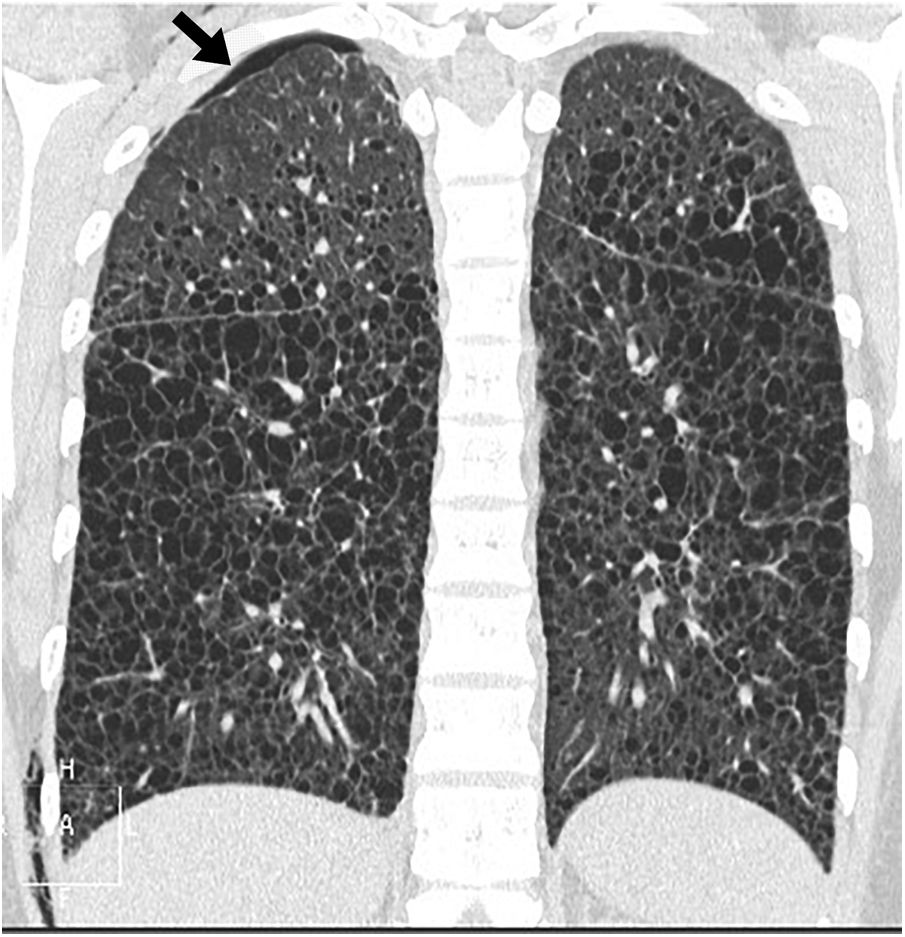

Amyloidosis and light-chain deposition diseaseThe term amyloidosis refers to a heterogeneous group of diseases that have in common the extracellular deposit of insoluble fibrillar proteins with green birefringence on Congo red staining. Amyloidosis can be systemic (80–90% of cases) or localised. Pulmonary involvement occurs in around 50% of cases and has three fundamental patterns of anatomical distribution: tracheobronchial, diffuse interstitial disease, and nodular parenchymal disease. The nodular pulmonary form is almost always a localised disease, with AL amyloid deposits, and is part of the differential diagnosis of diffuse cystic lung diseases. It is associated with collagen diseases, mainly Sjögren’s syndrome, although it also occurs in patients without connective tissue disorders and lymphoproliferative diseases, such as MALT lymphoma.10,16,48–52 CT shows multiple nodules of variable size (from less than 1cm to several centimetres), with smooth or spiculated borders, randomly distributed or predominantly in the lower lung fields, both peribronchovascular and subpleural, and with frequent calcification (up to 50%). Multiple cysts are seen along with the nodules (Fig. 12), which are thin-walled, randomly distributed, and calcified nodules are often seen on the cyst's wall or within it.10,48–51 The possible pathogenesis of the cysts includes airway stenosis due to infiltration of the bronchiolar wall by amyloid and inflammatory cells, with distal dilatation due to a valvular mechanism, rupture of the alveolar walls due to fragility as a result of amyloid deposition, and ischaemia secondary to the deposition of amyloid in the vascular walls.11,13,16,49 The differential diagnosis, especially in patients with Sjögren's disease, includes LIP, but in this disease the nodules do not calcify and poorly-defined centrilobular nodules are seen.

Pulmonary amyloidosis in cystic and nodular form. (A) The MIP (maximum intensity projection) image reconstruction in the coronal plane reveals air-filled cystic images in both lower lobes (arrows). (B) The MIP image in the transverse plane highlights the presence of bilateral pulmonary nodules with irregular contours corresponding to foci of amyloidosis (arrows).

Light-chain deposition disease of the lung is a very rare entity that is almost always associated with multiple myeloma or Waldenström's disease. It is characterised by an extracellular deposit of amorphous material and a lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate, especially in the kidney, but also in the wall of the alveoli and the small airway. Diffuse thin-walled cysts, nodules of millimetres to several centimetres, and lymphadenopathy can be seen on CT, as in amyloidosis, but unlike amyloidosis, the nodules rarely calcify, and there is no positivity for extracellular material on Congo red staining.2,10,53,54 It is usually a progressive disease that leads to respiratory failure and may require a lung transplant. Metalloproteinases have been implicated in tissue destruction leading to cyst formation.17

Other causes of diffuse lung cystsCystic pulmonary metastases: they can be seen in patients with sarcomas and squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck, but also with adenocarcinomas, with a predominance in the lower lobes (Fig. 13).

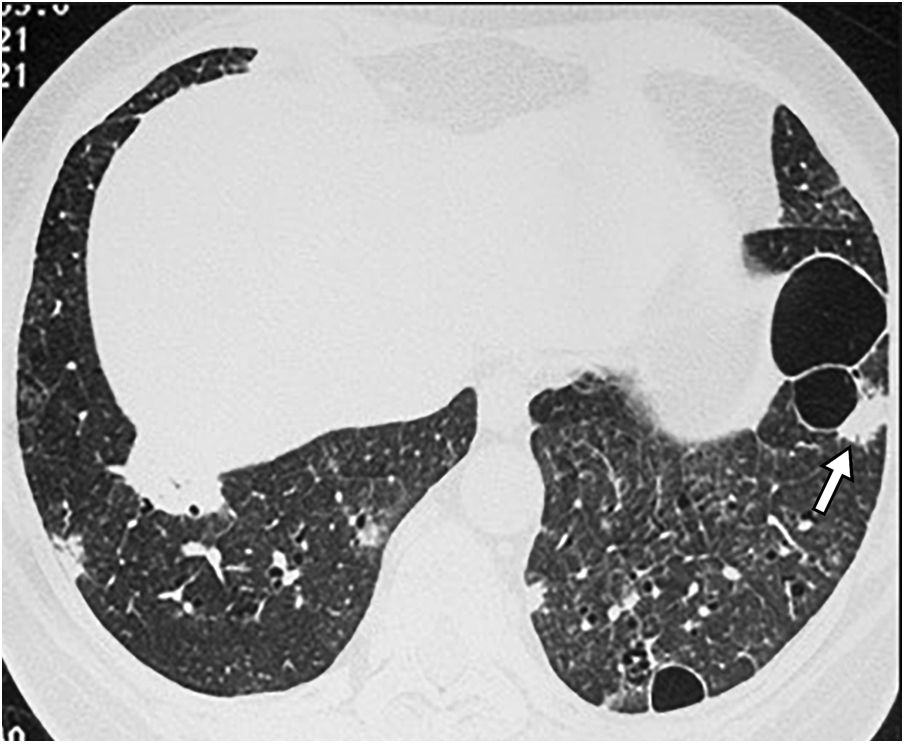

Infections: in infection by Pneumocystis jiroveci diffuse ground-glass opacities and reticulation are the dominant findings, but air-filled cystic lesions can be seen in up to 35% of patients (Fig. 14). They have different sizes, wall thicknesses and a diffuse distribution or with a predominance in the upper lobes, and they may resolve as the infection does. Coccidioidomycosis, a fungal disease endemic in the southwestern United States and Central and South American countries, manifests in chronic forms with cavitated nodules, but thin-walled cysts occasionally persist. Lung cysts may also be seen in echinococcosis, paragonimiasis, and mycobacterial infections. Laryngotracheobronchial papillomatosis, caused by the human papillomavirus virus, can present with pulmonary involvement more than 10 years after the diagnosis of tracheal-laryngeal involvement and is characterised by solid pulmonary nodules that evolve into round or irregular cystic lesions with a diffuse distribution, and with variable wall thickness, sometimes with air-fluid levels (Fig. 15).

Pulmonary tracheal papillomatosis in a 17-year-old male patient. (A) The CT image of the upper lung fields reveals a subcentimetre nodule in the tracheal wall corresponding to a papilloma. (B) The HRCT image of the lower lobes reveals multiple cystic images, some of them with an air-fluid level (arrow), corresponding to extensive bilateral involvement due to papillomatosis.

Sarcoidosis: Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic granulomatous disease, characterised by the formation of noncaseating granulomas in multiple organs. Cystic involvement is rare, generally occurring in patients with fibrotic sarcoidosis (clinical stage IV) and agglomerated cysts resembling a honeycomb pattern are identified (Fig. 16). It is speculated that these peripheral cysts could be attributable to a valvular mechanism secondary to peribronchial fibrosis or the accumulation of granulomas.55

Sarcoidosis with cystic involvement in a 57-year-old man. (A) The CT image of the upper lobes highlights the presence of air cysts that mimic a honeycomb pattern. (B) The coronal image reconstruction highlights the predominant involvement in the upper lobes, with associated volume loss.

Hypersensitivity pneumonitis (HP): HP is a diffuse lung disease caused by the inhalation of a broad spectrum of antigens that trigger a pathologic immune reaction in the lungs in predisposed individuals. Despite not being a characteristic radiological manifestation, in some cases, it presents bilateral air-filled lung cysts, of random distribution.56 (Fig. 17).

ConclusionsCystic lung diseases constitute a heterogeneous group of entities characterised by thin-walled, air-filled lesions with a more or less diffuse distribution. Differential diagnosis can be complex and the first step is usually to identify the true cystic nature of the lesions, as well as their diffuse distribution. It is essential to analyse the cysts' size, number, morphology and distribution, as well as the presence of other associated findings. High-resolution CT (HRCT) is the most useful diagnostic imaging technique in these diseases and often makes histological confirmation of the diagnosis unnecessary.

Authorship- 1

Person responsible for the integrity of the study: BCM, AGP and SPMF.

- 2

Study conception: BCM, AGP and SPMF.

- 3

Study design: BCM, AGP and SPMF.

- 4

Data collection: N/A.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: N/A.

- 6

Statistical processing: N/A.

- 7

Literature search. BCM, AGP and SPMF.

- 8

Drafting of the article: BCM, AGP and SPMF.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: BCM, AGP and SPMF.

- 10

Approval of the final version: BCM, AGP and SPMF.

Article authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.