To determine the efficacy and effectiveness of CT colonography in comparison with those of colonoscopy in screening for colorectal cancer.

Material and methodsWe systematically reviewed all the studies in the scientific literature that assessed the efficacy of CT colonography in screening for colorectal cancer. We excluded articles that assessed the efficacy of other screening techniques for colorectal cancer and those that used CT colonography in the diagnostic workup of suspected lesions or symptomatic patients. After a critical reading of the 213 references obtained, we selected nine studies.

ResultsThe specificity of CT colonography in screening for colorectal cancer was high, although it decreased with the diameter of the polyp to be detected. The sensitivity of CT colonography in the detection of polyps less than or equal to 6mm in diameter was very low and heterogeneous, although it was higher for polyps greater than 9mm in diameter.

ConclusionCT colonography has high specificity but very heterogeneous sensitivity, although in most cases it was not as sensitive or specific as conventional colonoscopy.

Determinar la eficacia y efectividad de la colonografía por tomografía computarizada (CTC) frente a la colonoscopia como pruebas de cribado para el cáncer colorrectal (CCR).

Material y métodosSe realizó una revisión sistemática de la literatura científica que incluyó todos los estudios que evaluaran la eficacia de la CTC como prueba de cribado del CCR. Quedaron excluidos aquellos artículos que analizaran la eficacia de otras técnicas de cribado para el CCR o los que utilizaran la CTC como técnica diagnóstica o en poblaciones sintomáticas. De las 213 referencias obtenidas se seleccionaron 9 estudios tras lectura crítica.

ResultadosLa especificidad demostrada para la CTC en el cribado del CCR fue alta y disminuía con el diámetro del pólipo a detectar. La sensibilidad para la CTC para detectar pólipos de diámetro igual o menor de 6mm resultó ser muy baja y heterogénea, aunque aumentaba para la detección de pólipos de más de 9mm de diámetro.

ConclusiónLa CTC demostró tener alta especificidad y una sensibilidad muy heterogénea, aunque en la mayoría de los casos no alcanzó los porcentajes de sensibilidad y especificidad logrados por la colonoscopia.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the major public health problems in developed countries. It is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States accounting for 11% of all cancer deaths.1 CRC accounts for approximately 210,000 deaths each year in Europe.2 Mean age of presentation is 69 years and most patients are older than 50 years at diagnosis. The 5-year survival rate is 90% when the cancer is found at a local stage, 68% if the cancer has spread to lymph nodes, and 10% if there are distant metastases.3,4 Unlike other types of cancer, CRC can be prevented by removing precancerous lesions5 or adenomas. Adenomas or polyps are classified according to diameter into three groups: diminutive (<5mm), small (6–9mm), and large (>10mm). Most polyps <10mm are non-adenomatous and only a small fraction of all adenomas is in advanced stage. The main characteristics of CRC are the long asymptomatic period, which can even last for up to 10 years, and the improvement in the prognosis in recent years. This, together with the easy detection of precursor lesions, suggests that CRC is an appropriate target for screening.6 Today, there is a wide range of technological options available for CRC screening of populations at moderate risk. These techniques can be classified into two categories: tests that detect mainly polyps and cancer providing images of these lesions (colonoscopy, flexible sigmoidoscopy and CT colonography [CTC]), and tests that detect mainly cancer but have low sensitivity for detecting polyps and characteristically lower sensitivity than imaging techniques for detecting neoplastic lesions (fecal immunohistochemical testing [FIT], Fecal DNA Testing [FDT] and fecal occult blood test). Colonoscopy has been considered the reference standard since it was first recommended by the main clinical practice guidelines in 2000. Colonoscopy provides direct visualization of the entire mucosal surface of the colon and, at the same time, it has the ability to biopsy and treat lesions. This technique requires colonic preparation and sedation may be used to improve patient tolerance.7 CTC, also known as virtual colonoscopy,8 is a minimally invasive imaging technique that allows inspection of the entire colon. This technique utilizes helical computed tomography (CT) to generate high-resolution 2D and 3D images that are subsequently interpreted by specialists. CTC has improved significantly since its introduction in the mid 90s, improving image quality, reducing reading time and radiation exposure to patients. CTC technique involves the following steps:

- 1.

Bowel cleansing with an osmotically active preparation, alone or in combination with contrast labelling or labelling and clear fluid diet without cathartic agents.

- 2.

Colon insufflation with carbon dioxide or room air via the rectum.

- 3.

Image acquisition using helical CT technology that moves the patient through a rotating X-ray beam. No IV contrast agent is required.

- 4.

Image processing and interpretation by means of software packages that simultaneously display 2D axial, coronal and sagittal images and 3D endoluminal views. Therefore, CTC brings advantages over the rest of CRC screening techniques as it provides rapid image acquisition of the entire colorectum, is minimally invasive, does not require sedation and is a low-risk procedure with few complications.7,8 As a result, CTC has been recommended by multiple medical societies as an effective alternative for CRC screening.9 However, the accuracy of CTC for detecting asymptomatic colorectal lesions remains controversial. This study aims to examine the available evidence supporting the efficacy of CTC for CRC screening against the current reference standard test, colonoscopy.

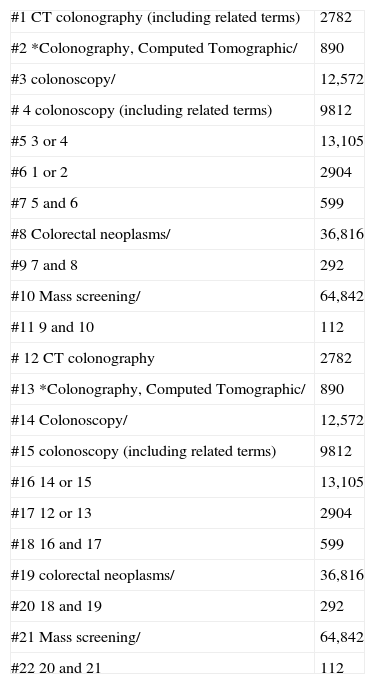

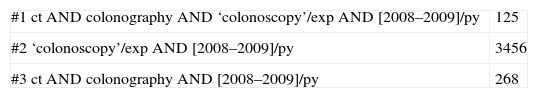

A systematic review of the scientific literature was conducted to identify the most relevant studies on the efficacy of CTC for CRC screening. To this end, the following databases were searched until 30 July 2009: Medline, Embase (Evidence Based Medicine), Cochrane Library, Tripdatabase, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination and E-Guidelines. The web sites of the American Cancer Society (ACS) and Programa de Actividades y de Promoción de la Salud (PAAPS) of the SemFyC (Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine) were also searched. The search was carried out by two independent reviewers, with no restrictions in terms of dates, language or type of study. The search strategies used for Medline, Embase and Cochrane are shown in Appendix A. For the rest of the databases, very open strategies for free text search were used. In addition, manual searches were performed for the list of references. All the articles aiming to assess the efficacy and safety of CTC as a screening test for CRC, either in isolation or in comparison with colonoscopy, were selected. Articles assessing the efficacy of CRC screening tests other than colonoscopy and CTC were excluded. Two independent reviewers conducted the critical appraisal and a qualitative and balanced summary of the selected studies, assessing their design and methodology followed. The quality of the articles was evaluated using the CASPe, AGREE and QUADAS tools for Systematic Reviews, Clinical Practice Guidelines and Clinical Trials, respectively.

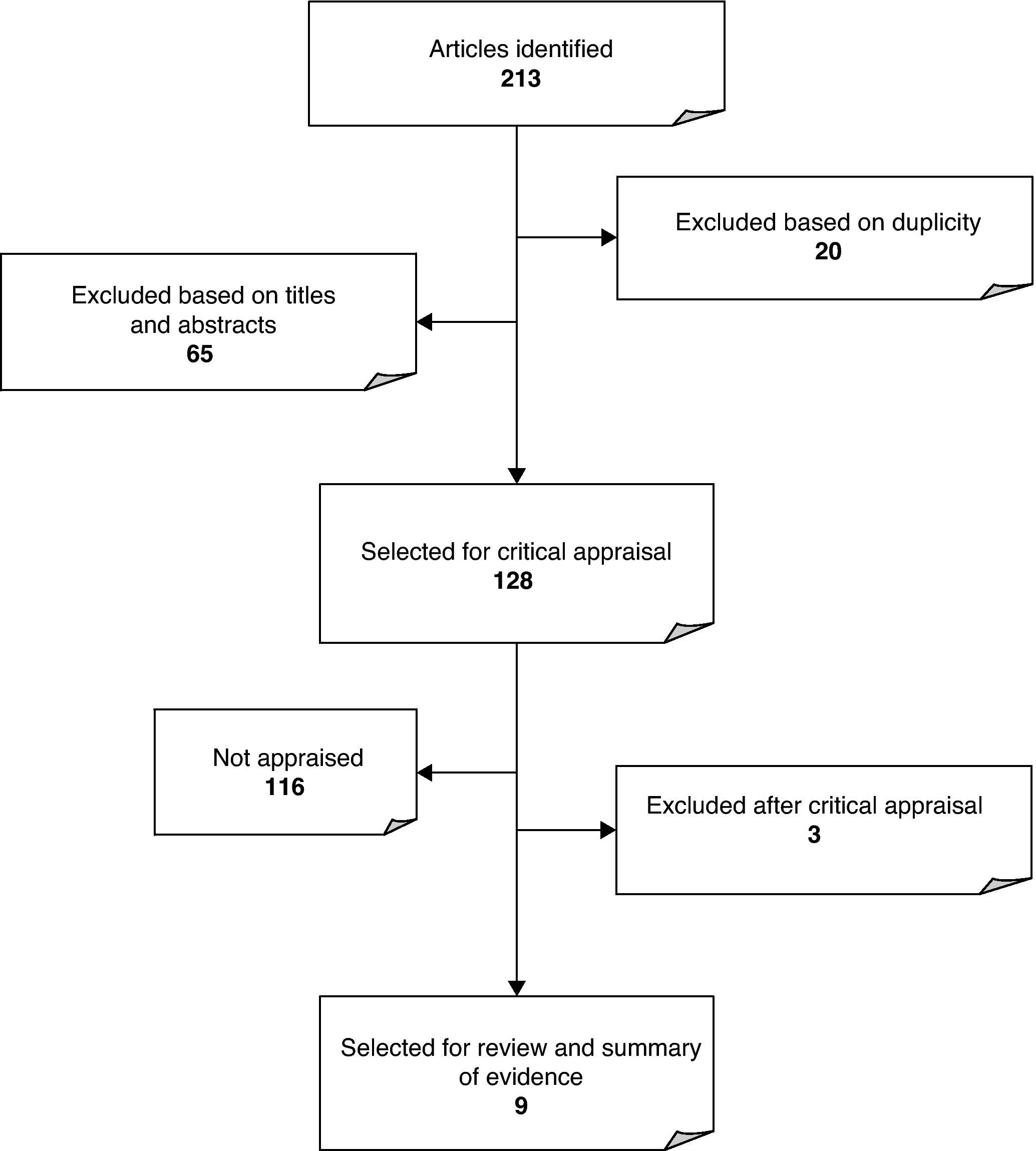

ResultsA total of 213 references corresponding to clinical trials, systematic reviews, full reports, original articles and clinical practice guidelines on the efficacy of CTC for CRC screening were selected. As shown in Fig. 1, 20 articles were duplicated, and 65 references were excluded because no data were found in the title or in the abstract in connection with the subject in question. As a result of the publication in 2008 of an updated systematic review by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force4 and the publication in 2005 of a meta-analysis by the American College of Physicians (ACP), from the remaining 128 articles only the clinical trials, reports issued by Evaluation Agencies and systematic reviews published after 2005 and not included in any of the above mentioned studies were selected. After excluding two studies because they did not deal with the subject presented in the abstract, nine articles remained for analysis (5 clinical trials, 2 systematic reviews, and 2 clinical practice guidelines). The QUADAS scale for assessing the quality of diagnostic tests revealed that the five articles showed good methodological quality, being the lower score 9 out of 14 items.10 All the articles included representative populations, described the selection criteria clearly and used an appropriate reference standard. However, the index test was often not properly described or the time period between reference standard and index test was not specified or was not followed. In three of the articles, it was unclear whether there were patients lost to the study and the reasons for that. Systematic reviews proved to have high methodological quality after CASPe, but showed some deficiencies concerning the inclusion of unpublished articles. The AGREE instrument revealed limitations regarding methodological aspects and funding; however, the results of the assessment were, in general, acceptable. Tables 1–3 show the results. The selected articles included 2 systematic reviews, 5 prospective studies and 2 clinical practice guidelines. The results on the efficacy of CTC for CRC screening are given in two ways11:

- •

Per-polyp. This describes the ability of CTC to detect a polyp. It is a measure of the ideal ability of the technique to detect CRC.

- •

Per-patient. This indicates the number of patients in whom at least one polyp of any size is detected. This reporting method is clinically more relevant since even if only one polyp is found on CTC, the patient is referred for colonoscopy that could reveal lesions not detected on CTC.

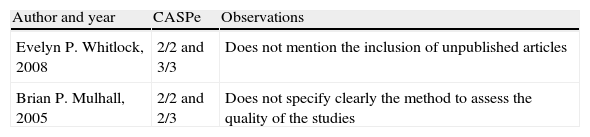

CASPe score for systematic reviews.a

| Author and year | CASPe | Observations |

| Evelyn P. Whitlock, 2008 | 2/2 and 3/3 | Does not mention the inclusion of unpublished articles |

| Brian P. Mulhall, 2005 | 2/2 and 2/3 | Does not specify clearly the method to assess the quality of the studies |

For CASPe appraisal, the two first sets of questions were asked, assigning a maximum of three point to each question. The score for each study is represented by two numerical expressions. The first one refers to the screening questions and the second to the set of itemized questions. These numerical expressions are represented by a ratio where the first number refers to the number of fulfilled items and the second number refers to the maximum score that can be obtained for that set of questions.

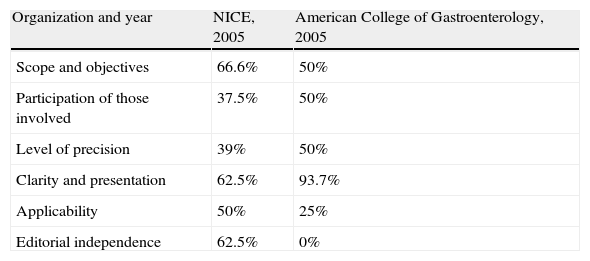

AGREE score for clinical practice guidelines.

| Organization and year | NICE, 2005 | American College of Gastroenterology, 2005 |

| Scope and objectives | 66.6% | 50% |

| Participation of those involved | 37.5% | 50% |

| Level of precision | 39% | 50% |

| Clarity and presentation | 62.5% | 93.7% |

| Applicability | 50% | 25% |

| Editorial independence | 62.5% | 0% |

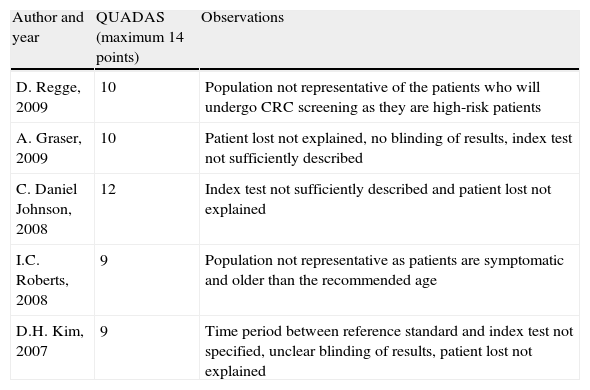

QUADAS score for diagnostic tests.

| Author and year | QUADAS (maximum 14 points) | Observations |

| D. Regge, 2009 | 10 | Population not representative of the patients who will undergo CRC screening as they are high-risk patients |

| A. Graser, 2009 | 10 | Patient lost not explained, no blinding of results, index test not sufficiently described |

| C. Daniel Johnson, 2008 | 12 | Index test not sufficiently described and patient lost not explained |

| I.C. Roberts, 2008 | 9 | Population not representative as patients are symptomatic and older than the recommended age |

| D.H. Kim, 2007 | 9 | Time period between reference standard and index test not specified, unclear blinding of results, patient lost not explained |

The two systematic reviews included for analysis were from the U.S. and were published in 2005 and 2008. The 2005 review12 also included a meta-analysis involving 33 studies that provide data from 6393 patients. The study reported per-patient sensitivity for each screening test and it was organized according to polyp size, type of scanner and type of image. Overall sensitivity was heterogeneous but tending to improve as polyp sized increased. In this respect, sensitivity for polyps <6mm was 48% (CI: 25–70%), 70% (CI: 55–84%) for polyps 6–9mm, and 85% (CI: 79–91%) for polyps >9mm. In contrast, per-patient specificity data were homogeneous: 92% (CI: 89–96%) for polyps <6mm, 93% (CI: 91–95%) for polyps between 6–9mm and 97% (CI: 96–97%) for polyps >9mm. The main limitations were the considerable methodological differences between studies. Therefore, CTC proved to be a highly specific screening test, but showed a wide range of sensitivities. This variability could be explained not only by the technical characteristics employed but also by the different types of collimator, scanners, and modes of image processing used. The 2008 systematic review12 by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) examined CT colonography screening in 4312 average-risk patients from four studies of good methodological quality. The major part of the results was represented by the studies conducted by Pickhardt et al. and by the American College of Radiology Imaging Network (ACRIN), which together represented 87% of patients. Pooled sensitivity for large adenomas (≥10mm) in these two studies was 92% (CI: 87–89%) with no heterogeneity detected between studies. These studies reported that CTC was comparable to colonoscopy for detecting large polyps, but not for smaller polyps (≤6mm). In this respect, the sensitivity of CTC reported by ACRIN was 78% (CI: 71–85%) and 88.7% (CI: 82.9–93.1%) reported by Pickhardt. Pooled sensitivity for small adenomas was not determined because between-study results were too different and statistically heterogeneous. However, data revealed that sensitivity for small adenomas tended to decrease as polyp diameter decreased. Per-patient specificity of CTC was statistically heterogeneous between the two largest studies. One of the studies (Pickhardt et al., 2003) clearly distinguished false-positive from false-negative results. This study used segmental unblinding and reported a specificity of 79.6% (CI: 77–82%) for lesions ≤6mm. In contrast, ACRIN reported a specificity of 88% for this type of lesion (CI: 84–92%); therefore, pooled specificity could not be obtained. Per-polyp sensitivity of CTC for adenomas ≥6mm was 86.2%. Complications resulting from CTC examination included only one case of bacteremia and a very low rate of perforations compared to colonoscopy (one case and six cases, respectively). Extracolonic findings occurred in 27–69% of patients who underwent CTC, but only 7–16% of patients undergoing CTC required additional diagnostic evaluation or surveillance. Regarding colonoscopy, there were no sufficient data to provide precise estimates of the per-patient sensitivity for adenomas of 6, 8 or 10mm, particularly for colorectal cancer detection, because of the small number of patients studied and the relatively few lesions found. The study concludes that CRC screening with CTC in average-risk populations is comparable to colonoscopy for detecting large adenomas (≥10mm) and CRC. However, when the study was conducted, there was not enough evidence to support that CTC is as sensitive as colonoscopy for the detection of small adenomas (≤6mm).

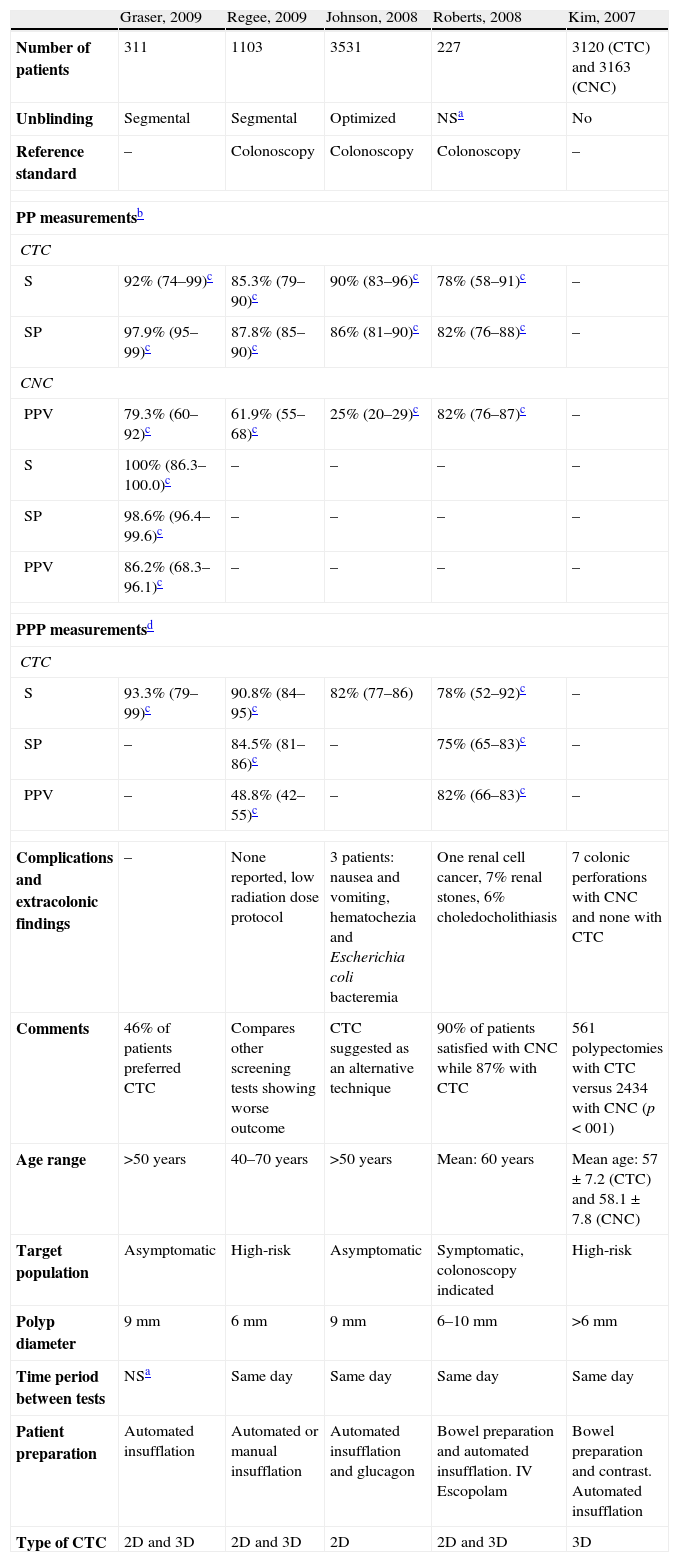

The prospective studies10,13–16 included a total of 8292 patients who were evaluated to determine the efficacy of CTC. All the studies used colonoscopy as reference standard in one single group of patients, apart from one study16 that organized two groups of patients to evaluate separately the efficacy of CTC and colonoscopy. Patients were asymptomatic, apart from the patients enrolled in one of the studies10 who were symptomatic. Age ranged between 40 and 70 years. One of the articles reported the results as descriptive data whereas the rest of the articles reported performance measurements of the techniques (sensitivity, specificity or predictive value). Table 4 shows the clinical trials published after 2007 including their main results and main methodological characteristics. The study published in 2007 by Kim16 pooled the data from two groups of patients, the majority of whom were asymptomatic. One of the groups underwent colonoscopic screening (No.=3163) and another underwent CTC (No.=3120) to determine the diagnostic performance of both techniques for CRC screening. CTC detected 123 advanced neoplasms (81.3% histologically proved), and colonoscopy found 121 (88.4% histologically proved). Overall, 7.9% of patients in the CTC group were referred for colonoscopy for rechecking the results. The number of resected polyps was 17.9% for CTC and 76.9% for colonoscopy, explained by the fact that only polyps >6mm in diameter underwent resection. The main limitation of the study was the lack of randomization, which could result in selection bias that would explain the different prevalences of advanced adenomas between the two groups. The study concluded that CTC and colonoscopy showed similar detection rates for advanced neoplasms, but the number of polypectomies and complications was significantly lower in the CTC group. Table 1 shows the results of the rest of the articles including data regarding per-patient and per-polyp sensitivity and specificity of CTC and colonoscopy.

Main characteristics of the studies.

| Graser, 2009 | Regee, 2009 | Johnson, 2008 | Roberts, 2008 | Kim, 2007 | |

| Number of patients | 311 | 1103 | 3531 | 227 | 3120 (CTC) and 3163 (CNC) |

| Unblinding | Segmental | Segmental | Optimized | NSa | No |

| Reference standard | – | Colonoscopy | Colonoscopy | Colonoscopy | – |

| PP measurementsb | |||||

| CTC | |||||

| S | 92% (74–99)c | 85.3% (79–90)c | 90% (83–96)c | 78% (58–91)c | – |

| SP | 97.9% (95–99)c | 87.8% (85–90)c | 86% (81–90)c | 82% (76–88)c | – |

| CNC | |||||

| PPV | 79.3% (60–92)c | 61.9% (55–68)c | 25% (20–29)c | 82% (76–87)c | – |

| S | 100% (86.3–100.0)c | – | – | – | – |

| SP | 98.6% (96.4–99.6)c | – | – | – | – |

| PPV | 86.2% (68.3–96.1)c | – | – | – | – |

| PPP measurementsd | |||||

| CTC | |||||

| S | 93.3% (79–99)c | 90.8% (84–95)c | 82% (77–86) | 78% (52–92)c | – |

| SP | – | 84.5% (81–86)c | – | 75% (65–83)c | – |

| PPV | – | 48.8% (42–55)c | – | 82% (66–83)c | – |

| Complications and extracolonic findings | – | None reported, low radiation dose protocol | 3 patients: nausea and vomiting, hematochezia and Escherichia coli bacteremia | One renal cell cancer, 7% renal stones, 6% choledocholithiasis | 7 colonic perforations with CNC and none with CTC |

| Comments | 46% of patients preferred CTC | Compares other screening tests showing worse outcome | CTC suggested as an alternative technique | 90% of patients satisfied with CNC while 87% with CTC | 561 polypectomies with CTC versus 2434 with CNC (p<001) |

| Age range | >50 years | 40–70 years | >50 years | Mean: 60 years | Mean age: 57±7.2 (CTC) and 58.1±7.8 (CNC) |

| Target population | Asymptomatic | High-risk | Asymptomatic | Symptomatic, colonoscopy indicated | High-risk |

| Polyp diameter | 9mm | 6mm | 9mm | 6–10mm | >6mm |

| Time period between tests | NSa | Same day | Same day | Same day | Same day |

| Patient preparation | Automated insufflation | Automated or manual insufflation | Automated insufflation and glucagon | Bowel preparation and automated insufflation. IV Escopolam | Bowel preparation and contrast. Automated insufflation |

| Type of CTC | 2D and 3D | 2D and 3D | 2D | 2D and 3D | 3D |

CNC: colonoscopy; CTC: CT colonography.

The two clinical practice guidelines9,17 included here recommend colonoscopy every 10 years for patients older than 50 years (1B). CTC and flexible sigmoidoscopy are recommended for patients who refuse colonoscopy or other screening test. CTC is recommended every five years (1C).

DiscussionIn the light of the results and the lack of studies on the impact of CTC on overall mortality rate for CRC, CTC appears as highly specific in the early detection of CRC (82–97.9%), particularly for polyps >9mm in diameter. However, the sensitivity of CTC varies widely among the different studies discussed here (78–92%), particularly for small- and medium-sized polyps (5–10mm in diameter). The appraisal reveals some of the factors that contribute to this wide range of results, including the lack of homogeneity in the technique (different type of collimators, number of detectors, or type of imaging) or the different ways of performing the test (type of contrast, patient preparation or degree of training of the radiologists involved in the studies). Most studies compare designs involving larger number of experienced colonoscopists to a smaller number of radiologists, which could a priori bias in favour of colonoscopy. The main limitation of the studies was using colonoscopy as reference standard because, although it has proven to be the most sensitive screening test for CRC detection18, colonoscopy cannot detect polyps <6mm in 27% of the cases19,20 (although only 1.2% of polyps <6mm show high-grade dysplasia21), and the detection rate for polyps <5mm is unknown. Furthermore, evidence shows that colonoscopy does not detect 6–12% of larger polyps (>10mm in diameter)19,22 leading to false-negative results. Therefore, acknowledgment of the faults inherent to colonoscopy means that the sensitivity of CTC may be being underestimated. Other limitations refer to the type of unblinding, type of population analyzed and presentation of the results. The studies examined here use segmental unblinding, where CTC findings are reported after the colonoscopist has completed the evaluation of a given segment, and optimized unblinding, where colonoscopic images are reviewed to find contradictory results. However, none of these methods ensures the repeated examination of each colonic segment or prevents the lack of detection of existing lesions detected on CTC. Regarding the target population, only two studies addressed symptomatic population >50 years of age. The rest of the studies addressed high-risk or asymptomatic patients, complicating thus the implementation of the results. Regarding the presentation of results, there is an explicit lack of information concerning the sensitivity for certain diameters or concerning the type of results reported (per-polyp or per-patient). As for the safety of the tests, short-term complications of CTC seem to be minimal, with low risk of perforation, particularly in asymptomatic patients. Long-term effects are unknown, particularly those related to radiation exposure and consequent cancer risks; however, the estimated risk of cancer after CTC is 0.14%.23 The radiation dose for a single CTC ranges from 5 to 10mSv and the standard dose level causing no harmful effects is set at 10–12mSv. Extracolonic findings are detected in 15–69%9 of CTC studies, which is problematic for screening purposes. These incidental findings could involve additional costs related to their surveillance. Between 7 and 16% of patients who undergo CTC screening will require follow-up tests or polypectomy.13,16 The current polyp size threshold that determines the surgical removal of a precancerous lesion and thus that determines the efficacy of CTC for CRC screening is a controversial issue among radiologists and gastroenterologists and it is based on the experts’ opinion rather than on clinical outcomes.4 Most experts agree on setting the threshold polyp size at ≥6mm. However, some studied have reported that a 10mm threshold for polypectomy would detect the majority of clinically relevant lesions.16 The subsequent management of lesions detected on CTC is also worth addressing. The relevance and treatment of diminutive adenomas is under discussion. Some studies agree on not reporting diminutive adenomas since cancer prevalence among patients with this type of polyps is 0.1%. Two approaches for the management of polyps 6–9mm in diameter are suggested: colonoscopic polypectomy or CTC surveillance every 3 years for patients with one or two polyps <10mm. The latter allows greater effectiveness in the detection and removal of advanced neoplasms, since only those that increase size over the follow-up period are removed. Colonoscopic polypectomy is recommended for larger polyps or in patients with three small polyps. Little is known about the costs of CTC as screening tool. A 2008 study16 estimated the costs of screening CTC and concluded that for CTC to reach the cost of colonoscopy screening it should be performed every five years with referral of polyps ≥6mm in diameter. Similarly, for the CTC to be as cost-effective as colonoscopy, the costs should not exceed 43% of colonoscopy costs ($662). It is also worth noting that patients’ preferences can vary depending on whether they belong to a high-risk population or to an asymptomatic population. According to existing data, 49.8% of high-risk patients would prefer CTC screening.12 The use of CTC could increase participation in CRC screening. In short, given the lack of homogeneous results on the efficacy of CTC and until there is sufficient evidence on its sensitivity and reliability, CTC cannot be recommended for mass use despite the relevance of the use of oral contrast with no cathartic agents for bowel preparation and the controversial argument concerning the potential reduction in the number of patients screened with CTC that would require colonoscopy. Thus far, colonoscopy is the technique of choice for CRC screening and CTC is not considered comparable to colonoscopic screening for several reasons. First, in comparison with CTC, the evidence supporting the impact of colonoscopic screening on CRC incidence and mortality is conclusive. Second, CTC requires 5-year follow-up intervals against the 10-year interval recommended for colonoscopy. In addition to this, extracolonic findings on CTC may involve additional costs. In view of these circumstances, CTC is currently considered an alternative to colonoscopy in those patients who refuse colonoscopy or patients with contraindications to colonoscopy, and it might be a selective filter for therapeutic colonoscopy in the detection of advanced neoplasms.

AuthorshipJuliana Ester Martín-López: evidence search, assessment of the methodological quality, synthesis of the results and drafting of the study; Ana María Carlos-Gil: methodological support and assessment of methodological quality of evidence; Luis Luque-Romero: external reviewer and supervision of the study; Sandra Flores-Moreno: external reviewer. All the authors have approved and read the final version of the article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Database research strategies.

| #1 CT colonography (including related terms) | 2782 |

| #2 *Colonography, Computed Tomographic/ | 890 |

| #3 colonoscopy/ | 12,572 |

| # 4 colonoscopy (including related terms) | 9812 |

| #5 3 or 4 | 13,105 |

| #6 1 or 2 | 2904 |

| #7 5 and 6 | 599 |

| #8 Colorectal neoplasms/ | 36,816 |

| #9 7 and 8 | 292 |

| #10 Mass screening/ | 64,842 |

| #11 9 and 10 | 112 |

| # 12 CT colonography | 2782 |

| #13 *Colonography, Computed Tomographic/ | 890 |

| #14 Colonoscopy/ | 12,572 |

| #15 colonoscopy (including related terms) | 9812 |

| #16 14 or 15 | 13,105 |

| #17 12 or 13 | 2904 |

| #18 16 and 17 | 599 |

| #19 colorectal neoplasms/ | 36,816 |

| #20 18 and 19 | 292 |

| #21 Mass screening/ | 64,842 |

| #22 20 and 21 | 112 |

Please cite this article as: Martín-López JE, et al. Eficacia de la colonografía por tomografía computarizada frente a la colonoscopia como prueba de cribado del cáncer colorrectal. Radiología. 2011;53:355–63.