To present the results of a multidisciplinary study of two tertiary hospitals, together with urology services, on 102 consecutive patients not candidates for surgery treated for more than 6 years, in whom prostatic arteries were embolised for the treatment of benign hyperplasia.

Material and methodsFrom December 2012 to February 2019, 102 patients with symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) not candidates for surgery or who explicitly rejected surgery, with an average age of 73.9 years (range 47.5–94.5), underwent prosthetic embolisation. The patients were followed up by questionnaires on urinary symptoms, sexual function and impact on quality of life, as well as measurement of prostate volume, uroflowmetry and prostate specific antigen (PSA) at one, 3 and 6 months and one year following the procedure.

ResultsThe technique was successful in 96% of patients (76.2% bilateral and 19.8% unilateral). The mean duration of the procedure was 92min and of the radioscopy 35.2min. Statistically significant changes were demonstrated (p<.05) in PSA, peak urinary flow, QoL (quality of life) questionnaire and the International Index of Erectile Function (IPSS). PSA had reduced by 58% from baseline at 3 months. Similarly, the Qmax had increased significantly by 63% in the third month following embolisation. A significant improvement in the QoL and IPSS tests was achieved, with a reduction of 3.7 points and a mean 13.5 points, respectively, at one year’s follow-up. Prostate volume showed a non-statistically significant decrease at follow-up of one year following treatment. A series of minor complications was collected, no case of which required hospital admission.

ConclusionsProstatic embolisation for the treatment of BPH proved an effective and safe technique in patients who were not candidates for surgery.

Presentar los resultados de un estudio multidisciplinar de dos hospitales terciarios, junto a los servicios de urología, sobre 102 pacientes consecutivos no candidatos a cirugía tratados durante más de 6 años, en los que se realizó embolización de arterias prostáticas para el tratamiento de la hiperplasia benigna.

Material y métodosDesde diciembre de 2012 a febrero de 2019, 102 pacientes con síntomas de hiperplasia benigna de la próstata (HBP) no candidatos a cirugía o que la rechazaron explícitamente, con una edad media de 73,9 años (rango 47,5–94,5), fueron sometidos a embolización prostática. Se llevó a cabo un seguimiento de estos a través de cuestionarios sobre la sintomatología urinaria, función sexual e impacto en la calidad de vida, así como la medición del volumen prostático, uroflujometría y antígeno prostático específico (PSA) al mes, 3 y 6 meses y al año del procedimiento.

ResultadosLa técnica fue exitosa en un 96% de los pacientes (76,2% bilateral y 19,8% unilateral). El tiempo de duración media del procedimiento fue de 92 minutos y el de radioscopia, de 35,2 minutos. Se demostraron cambios estadísticamente significativos (p<0,05) en el PSA, el flujo urinario pico, el cuestionario QoL (Quality of life) y el International Index of Erectile Function (IPSS). El PSA disminuyó un 58% a los 3 meses respecto al valor inicial. Asimismo, el Qmáx aumentó de manera significativa en un 63% al tercer mes tras la embolización. Se obtuvo una mejoría significativa en los test QoL e IPSS, con una disminución de 3,7 puntos y 13,5 puntos de media, respectivamente, al año de seguimiento. El volumen prostático mostró una disminución no estadísticamente significativa al año, tras el tratamiento. Se han recogido una serie de complicaciones menores, que en ningún caso requirieron ingreso hospitalario.

ConclusionesLa embolización prostática para el tratamiento de la HPB demostró ser una técnica eficaz y segura en pacientes no candidatos a cirugía.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is one of the most common disorders in our society. The incidence in men over 60 is more than 50% and increases with age.1 It is characterised by a range of urinary symptoms which have a great impact on quality of life, such as increased frequency of micturition, nocturia, urinary urgency, incomplete emptying of the bladder and urinary retention.

The first experience with the procedure of prostate embolisation was reported by DeMeritt2 just after the turn of the millennium, and was performed with the aim of controlling the severe haematuria in patients with BPH after biopsy. In that study, not only were they able to control haematuria, but they incidentally discovered that patients showed a decrease in prostate volume (PV) and an improvement in BPH-related symptoms. A few years later, two experimental studies were conducted in animals with the aim of testing the efficacy and safety of prostate embolisation (PE).3,4 Both studies demonstrated the efficacy of the technique in reducing prostate volume, and the safety of selectively administering particles into the prostate arteries without undesirable effects on adjacent organs and with intact sexual function. More recently, a number of studies have been published advocating PE as an effective and safe technique for the control of BPH symptoms, including the randomised studies by Gao et al.5 and Carnevale et al.6 on prostate embolisation compared to transurethral resection of prostate (TURP). There are also numerous meta-analyses,7,8 systematic reviews9 and other studies of case series on this subject.10–15

We present the experience of two tertiary centres with similar characteristics in which PE has been proposed as a treatment for BPH in patients who are not candidates for surgery, obtained from a retrospective study over more than six years.

Material and methodsOver a period of more than six years (from December 2012 to February 2019), a prospective observational study with retrospective analysis of the data was carried out on 102 patients from the two participating centres. The mean age was 73.9 (range 47.5–94.5 years). All patients signed the corresponding informed consent form and the study was approved by the hospital's clinical research committee.

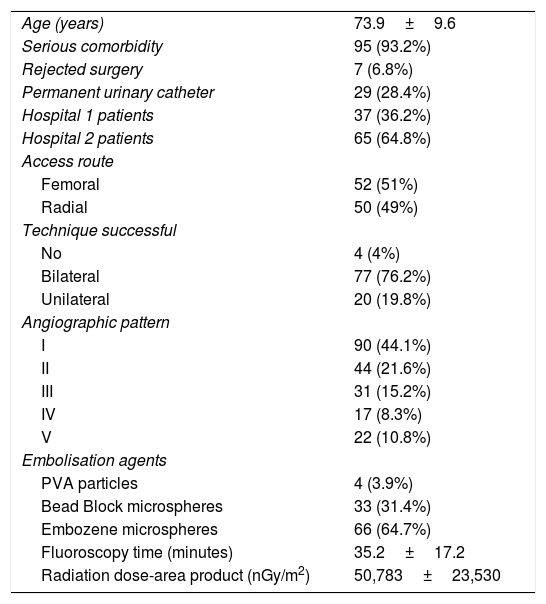

All patients had been referred from the Urology department, meeting restrictive inclusion criteria. All the patients included had moderate-to-severe urinary tract symptoms (International Prostate Symptom Score [IPSS] >8) attributed to BPH and failure of medical treatment for six months. Additionally, they were patients who were not candidates for surgery due to high associated comorbidity or because they expressly rejected the surgery. The exclusion criteria essentially comprised allergy to iodinated contrast, severe renal failure (serum creatinine >2mg/dl) or known history of prostate and/or bladder cancer, as well as non-patent prostate arteries in previous computed tomography (CT). Of the 102 patients, 29 had a permanent urinary catheter in situ (Table 1).

Baseline and demographic characteristics of all patients in the sample.

| Age (years) | 73.9±9.6 |

| Serious comorbidity | 95 (93.2%) |

| Rejected surgery | 7 (6.8%) |

| Permanent urinary catheter | 29 (28.4%) |

| Hospital 1 patients | 37 (36.2%) |

| Hospital 2 patients | 65 (64.8%) |

| Access route | |

| Femoral | 52 (51%) |

| Radial | 50 (49%) |

| Technique successful | |

| No | 4 (4%) |

| Bilateral | 77 (76.2%) |

| Unilateral | 20 (19.8%) |

| Angiographic pattern | |

| I | 90 (44.1%) |

| II | 44 (21.6%) |

| III | 31 (15.2%) |

| IV | 17 (8.3%) |

| V | 22 (10.8%) |

| Embolisation agents | |

| PVA particles | 4 (3.9%) |

| Bead Block microspheres | 33 (31.4%) |

| Embozene microspheres | 66 (64.7%) |

| Fluoroscopy time (minutes) | 35.2±17.2 |

| Radiation dose-area product (nGy/m2) | 50,783±23,530 |

Virtually all of the patients had a CT angiogram prior to the procedure and, in cases where, in the operator's opinion there was any doubt about the prostatic nature of the catheterised artery, cone-beam CT was performed.

We studied the angiographic patterns14 and classified them into five groups (I–V).

Technical embolisation procedureProstate embolisation was performed by digital subtraction angiography, using the systems Angiostar Plus and Artis Zee (Siemens, Germany).

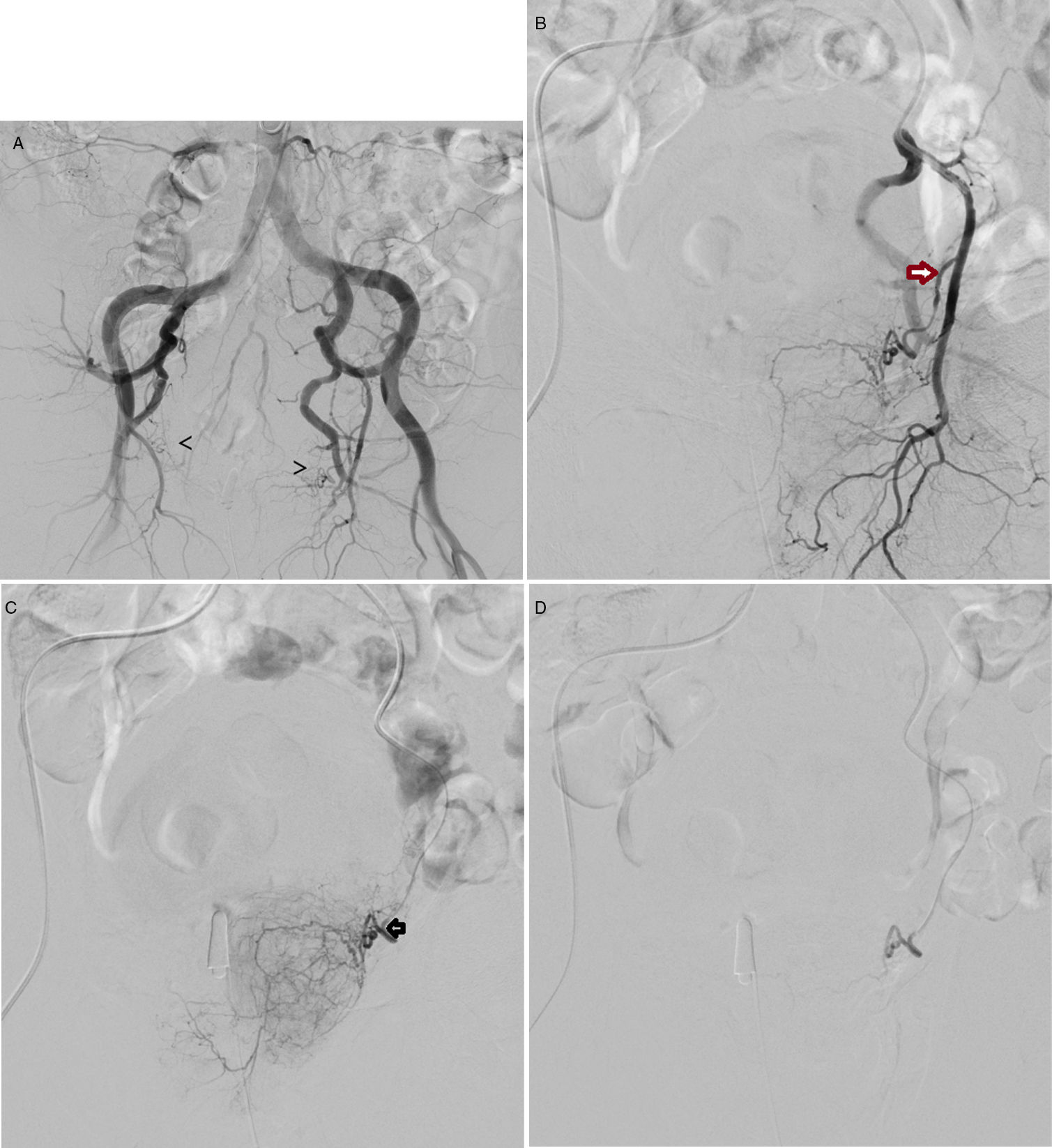

The access route used was either common femoral (Fig. 1) or radial with local anaesthesia.

(A) Pelvic arteriogram prior to the selective embolisation of prostate arteries, in which the origin of both arteries is indicated with arrows. B) Selective arteriogram of left internal iliac artery, with 10° cranial and 35° ipsilateral angulation, with the aim of identifying the exit of the inferior vesical artery/prostate artery (arrow). C) Selective catheterisation, with microcatheter in the left prostatic artery (arrow). Prior to the embolisation with 250-micron microparticles. D) Follow-up angiogram post-embolisation, which shows the vessel to be completely sealed; in this case the left prostatic artery.

The standard procedure for PE15 consists of performing a pelvic aortogram and then a selective angiogram of both internal iliac arteries in order to identify the prostate arteries, which will be catheterised with microcatheters in order to be embolised.

The microcatheters used were Progreat 2.7 (Terumo, Japan), Progreat 2.4 (Terumo, Japan), Renegade HIFLOW Fanthom (Boston Scientific, USA) and Rebar 18 (Covidien-Medtronic, USA). In one of the two hospitals that took part in the study, where the preference was for radial access, longer guide catheters were used (from 120 to 130cm).

The embolisation of prostate arteries (PA) was performed with Embozene microspheres (Celonova, Boston Scientific, USA) of 250–400 microns in diameter as first choice, although non-spherical microparticles made of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) particles (Contour 250–350 microns, Boston Scientific, USA), and Bead-Block microspheres (Terumo, Japan) of 300–500 microns in diameter were also used. The PA were considered embolised when the antegrade flow ceased completely (the PErFecTED [Proximal Embolisation First, Then Embolise Distal] technique was not used in any of the cases).12

Statistical design for the studyVariables studied: IPSS, Quality of Life (QoL), PV, maximum urinary flow rate (Qmax) and PSA.

The quantitative variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation and the categorical or qualitative variables as number (percentage). To compare categorical or qualitative variables, the chi-square test was used, with the Fisher test reserved for when the application conditions were not met. To compare quantitative variables before/after, the paired sample t-test was used. When there were more than two variables, analysis of variance with post-hoc tests were used. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

The follow-up consisted of clinical assessment at the source clinics, urodynamic study, PSA, completion of the IPSS questionnaire and the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF-5), and trans-abdominal ultrasound with ellipsoid measurement, to calculate the PV at one month, three months, six months, one year (and two years in some cases).

ResultsFrom December 2012 to February 2019, between the two hospitals, 102 patients had prostatic embolisation (37 patients in one and 65 in the other).

Technical success was achieved in 96% of cases (98 of 102), defined as the embolisation of at least one of the prostate arteries. In 78 cases (76.2%), bilateral embolisation was possible and in 20 cases (19.8%), unilateral only. In four patients (4%), neither of the prostate arteries could be catheterised, either because of occlusion due to atheroma, tortuosity or a bad angle at the origin of the prostate artery, and the technique was therefore considered to have failed.

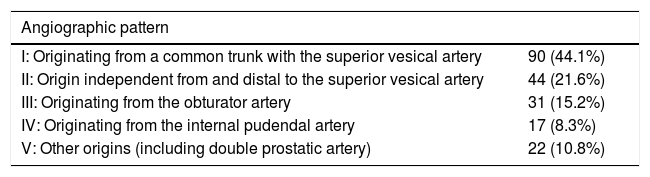

The angiographic patterns registered were: I (n=90 cases); II (n=44); III (n=31); IV (n=17); and V (n=22) (Table 2). The access route to perform the technique was either femoral (52 cases; 51%) or radial (50 cases; 49%). There were no statistically significant differences in the technical or clinical success associated with the different vascular patterns or access routes.

Characteristics of angiographic patterns according to the origin of the prostate artery.

| Angiographic pattern | |

|---|---|

| I: Originating from a common trunk with the superior vesical artery | 90 (44.1%) |

| II: Origin independent from and distal to the superior vesical artery | 44 (21.6%) |

| III: Originating from the obturator artery | 31 (15.2%) |

| IV: Originating from the internal pudendal artery | 17 (8.3%) |

| V: Other origins (including double prostatic artery) | 22 (10.8%) |

Taken from: Assis et al.14

The mean fluoroscopy time was 35.2min (range: 11–87min) and the total procedure time was 92min (range: 90–190min). The mean dose-area product was 50,783 (range: 3496–93,899μGy/m2).

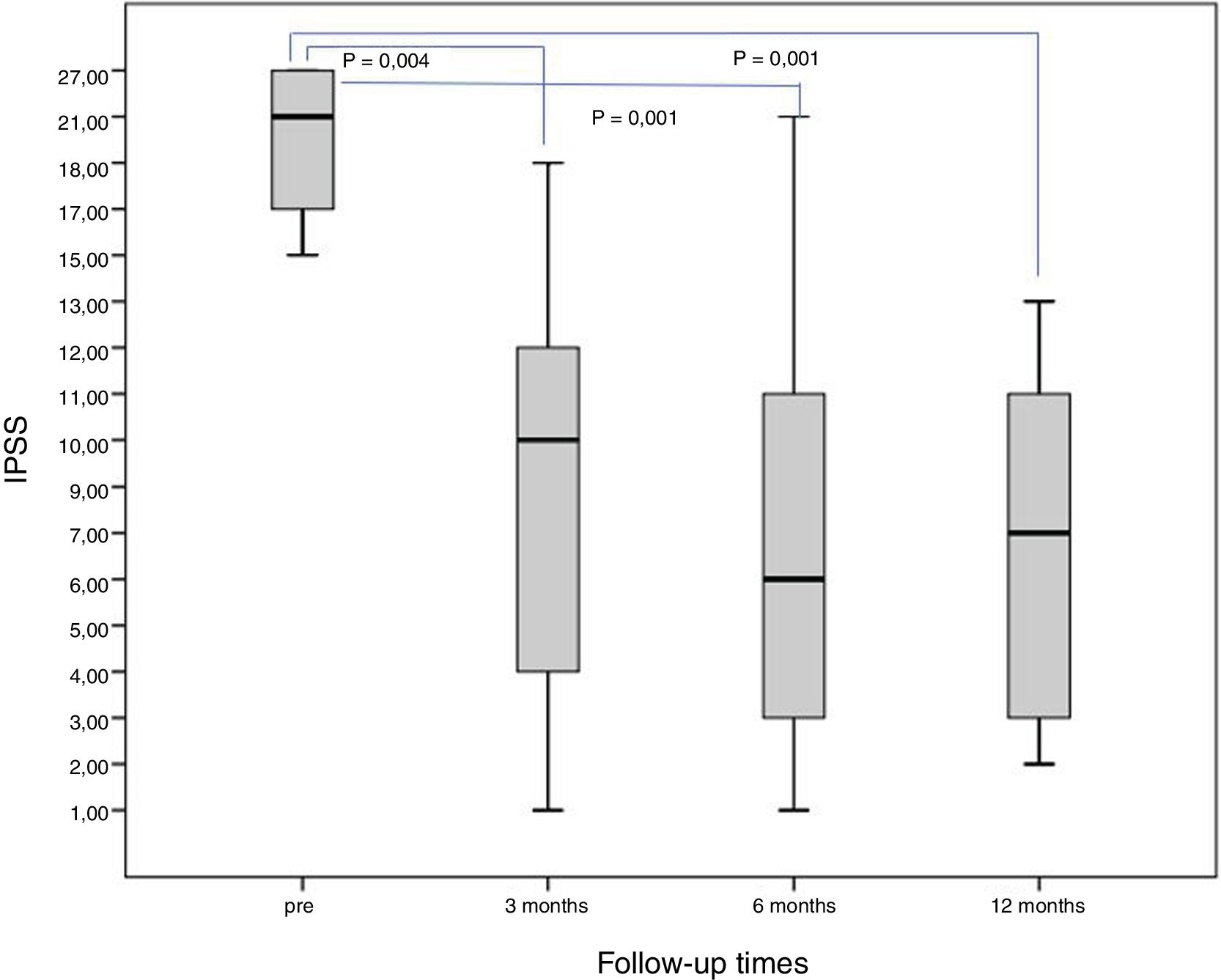

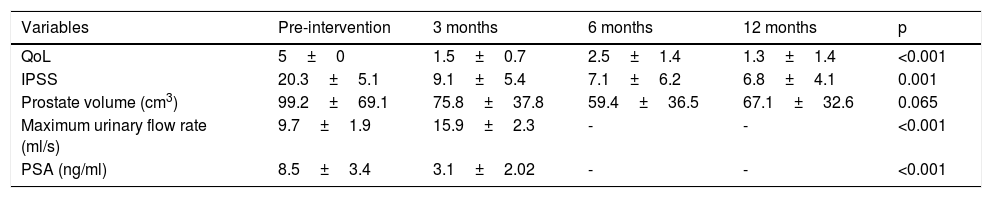

Qualitative variables (IPSS, QoL)The baseline IPSS was 20.3±5.1 points, and a significant improvement was achieved when comparing the results at three, six and 12 months (p<0.05) (Fig. 2).

The QoL scores also reduced significantly, with a mean pre-treatment of 5±0, with a statistically significant decrease (p<0.001) of 3.7 points at 12 months.

Quantitative variables (PV, PSA, Qmax)With the baseline PV at 99.2±69.1cm3, there was a significant reduction of 23.6% at three months and 40% at six months post-embolisation. After six months, the volume seemed to increase slightly, with a mean of 67.1±32.6 cm3 one year post-embolisation (reduction of 32% at one year). These PV figures show a slight fall in effectiveness (from 40% to 32%) and, although not statistically significant (p=0.065), there is a decreasing trend, which would perhaps be confirmed with larger series or longer follow-up.

The Qmax did show a significant increase; from a baseline of 9.7ml/s ± 1.9, Qmax had risen to 15.9±2.3ml/s three months after PE (p<0.001).

The baseline PSA was 8.5±3.4ng/ml, with a statistically significant reduction at three months of 3.1±2.02ng/ml (p<0.001).

All results data are summarised in Table 3.

Clinical response variables assessed pre-intervention and at 3, 6 and 12 months.

| Variables | Pre-intervention | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL | 5±0 | 1.5±0.7 | 2.5±1.4 | 1.3±1.4 | <0.001 |

| IPSS | 20.3±5.1 | 9.1±5.4 | 7.1±6.2 | 6.8±4.1 | 0.001 |

| Prostate volume (cm3) | 99.2±69.1 | 75.8±37.8 | 59.4±36.5 | 67.1±32.6 | 0.065 |

| Maximum urinary flow rate (ml/s) | 9.7±1.9 | 15.9±2.3 | - | - | <0.001 |

| PSA (ng/ml) | 8.5±3.4 | 3.1±2.02 | - | - | <0.001 |

The quantitative variables are expressed as mean±standard deviation and the categorical variables as a number (percentage).

PSA: prostate-specific antigen; IPSS: International Prostate Symptom Score; QoL: quality of life.

Of the 98 patients, 86 had no undesirable side effects (87.7%). Among the complications recorded, there were two patients with erectile dysfunction (2%), two with urinary infection (2%), four suffered severe pubic pain after the procedure (4%) and there were four cases of genital ulcers (4%), which reversed with local treatment. In our study, all of the complications of PE were minor (grade I/II) according to the Clavien-Dindo classification16 and none of the cases required admission to hospital.

Medium-term follow-upOver the course of the follow-up at one month, three, six and 12 months, there was a recurrence of urinary symptoms in some patients. Of the 29 patients who had permanent urinary catheters before treatment, nine developed acute urinary retention within the first three to six months post-embolisation and had to be re-catheterised on a permanent basis; this meant that the total clinical success in terms of catheter withdrawal was 69%.

Similarly, analysing the reappearance of symptoms, and consequently clinical failure, four patients ended up having to have TURP within three to six months post PE due to symptom recurrence. One patient was treated with radiotherapy due to non-surgical prostate cancer three months after embolisation, and another four patients with the same diagnosis were treated by prostatectomy. The abrupt elevation of PSA levels and the suggestive image on follow-up ultrasound led to a biopsy being taken and, as it was positive, the operating theatre. In our series, one of the patients had early recurrence of symptoms within one month of the embolisation and was re-embolised, with subsequent improvement.

There were four deaths in the first year of follow-up after the PE due to the progression of their underlying disease or natural causes.

From these data, it can be concluded that the clinical success rate is 92.9% at three months, 85.7% at six months and 81.6% at one year.

DiscussionAlthough embolisation is a widely established technique for the treatment of different disorders by interventional radiology, in BPH it is not the reference standard. In patients with symptoms of BPH, the standard technique at present is TURP, although it has its limitations in older patients with significant comorbidities. PE can be a therapeutic option in this type of patient, in whom it has proven to be a safe and effective technique.17–19

Our study recorded technical success in 96% of the patients by achieving embolisation of at least one of the prostate arteries (76.2% bilateral and 19.8% unilateral), figures that are consistent with other studies which report success rates of 90–100%.20,21

The vascular anatomy in the male pelvis is complicated, with anatomical variants common. The origin of the prostate arteries varies and they can become very tortuous or elongated, especially in older patients such as those in our study.22,23 In addition, atheroma can prevent catheterisation of the prostate arteries, so sometimes only unilateral treatment can be performed, as in 19.8% of our cases. Although the main aim of PE is to embolise both prostate arteries, Bilhim et al. described symptomatic improvement in half of those patients in whom only unilateral treatment was possible.24

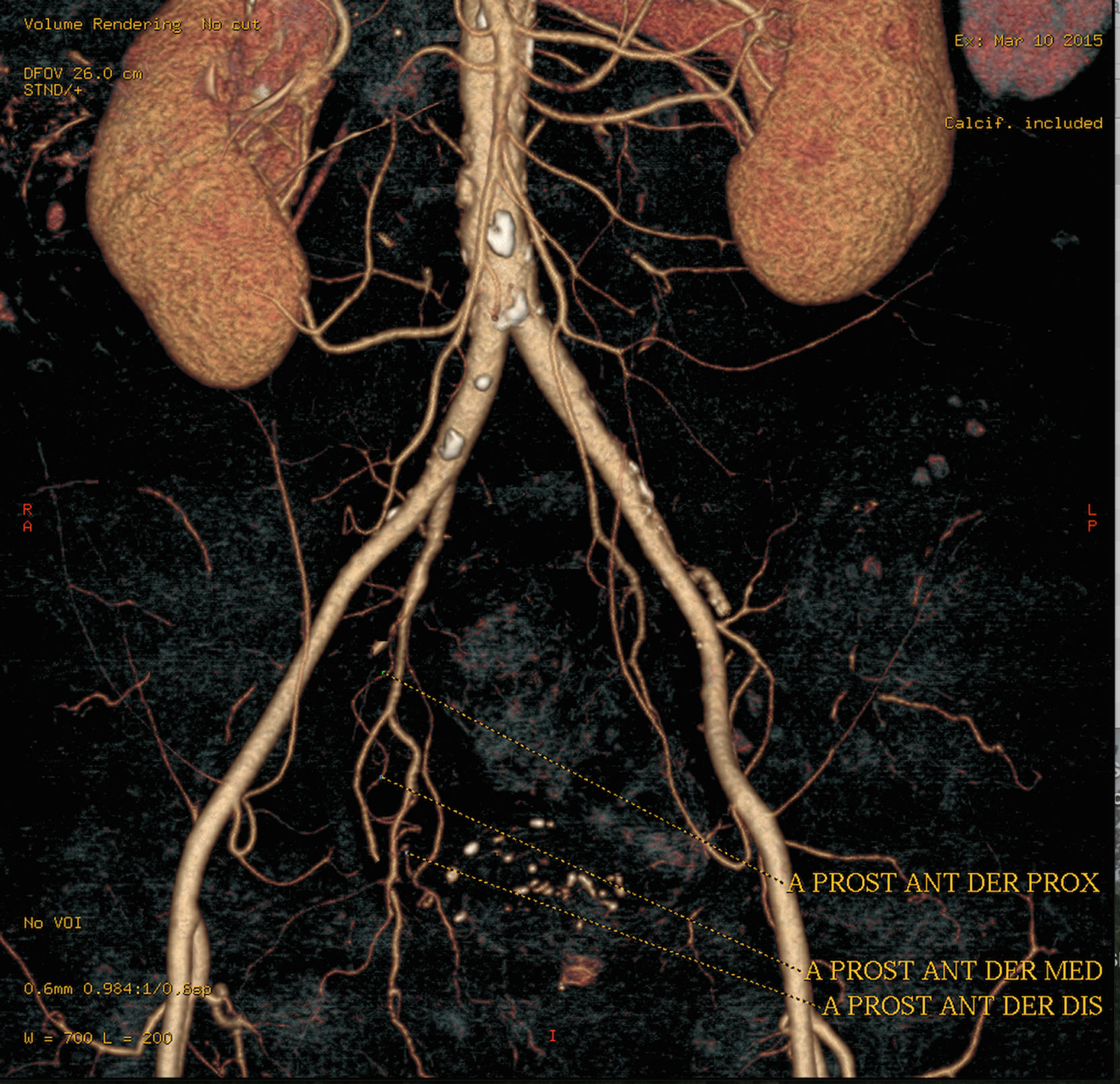

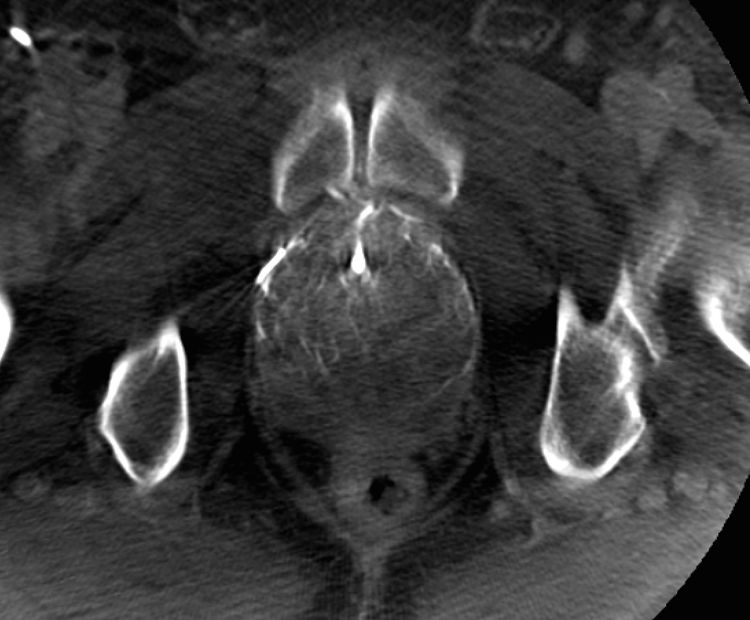

Performing a CT angiogram prior to treatment helps to select the appropriate patients for the technique and provides information about the anatomical variants (Fig. 3). Pisco et al. proposed the routine use of CT before the procedure some time ago20 and we did so in practically all our patients. Cone-beam CT is another useful imaging tool during the procedure (Fig. 4), to confirm that the prostate artery has actually been catheterised and to rule out any type of anastomosis in order to avoid unwanted ischaemic complications.25

(A) Cone beam computed tomography image (axial section) to demonstrate the correct catheterisation of the prostate artery prior to embolisation: through a microcatheter and with 5 seconds of delay in Dyna-CT form, diluted contrast is introduced, marking the area of the half of the gland vascularised by said vessel.

Three months after the embolisation, a significant increase was found in the Qmax (p<0.001) (63%) similar to the 45–54% obtained by other authors.26,27

Our study found the reduction in PV to be 32% at 12 months, similar to the figures found by other authors at the same point of follow-up, in the range of 22–41%.11,28,29 No relationship has been demonstrated between clinical improvement and volume reduction beyond one year.11 In our series, it is striking that the prostates were large (mean 100g), mirroring the series in other studies with large prostates,30–35 which reach similar conclusions on this aspect.

In terms of PSA levels, a 58% decrease was identified at three months after embolisation. These figures fall within those reported in the scientific literature (38% and 64%) for the same follow-up time after PE.11,29

Last of all, the most important results are those related to the patients' symptoms, particularly concerning the IPSS and the QoL. In our patients, the IPSS improved by 66% (mean decrease of 13.5 points) at 12 months of follow-up, in line with that reported by other authors (57%, 50% and 69%, respectively).11,26,28

Our study also identified an improvement in the QoL test one year after embolisation, with a mean decrease of 3.7 points. Our data corroborate the improvement already reported by other authors,20,28,29 who obtained mean reductions of 2,4, 2,5 and 5,6 points, respectively.

Our series consisted of mostly non-surgical patients in whom, as in other series,31,32 PE led to improvement in quantitative and qualitative variables, which leads us to think that this is the present and the future of the technique in our setting.

In the subgroup of patients who had urinary catheters prior to embolisation, the catheters could be removed in 69% of cases (20 of 29). However, this figure is somewhat lower than the 80.5–100% reported in the scientific literature for this very specific group of patients.31,33–37

Our study does have certain limitations. It was a retrospective study with no control group undergoing another technique for the treatment of BPH symptoms. The variables at six and 12 months (PSA and Qmax) were not fully recorded, and post-void residual urine was only measured in some patients, not systematically in all follow-up ultrasounds, so there were insufficient data for statistical analysis. Moreover, the results in terms of changes in the IIEF questionnaire are not assessable in our study; we only have isolated values, as our patients were very elderly and many either claimed not to have sexual relations or refused to answer the questionnaire.

Lastly, it is important to point out that although the trend in world literature is to focus on continuing to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of prostate embolisation with studies with large series of patients (n=630) followed up long-term37 or national multicentre studies such as UK-ROPE with 216 embolised patients,38 and even the recent publication of another randomised study,39 the reality of the day-to-day in our routine practice is quite different. In most of the interventional radiology units here in Spain, the patients referred to us for prostate artery embolisation belong to a subgroup in which the urologist has completely ruled out surgical management.

Many of the patients with symptoms of BPH and old age have significant associated comorbidities, which mean a high surgical risk. In conclusion, through our study, we want to show that PE is an effective and safe technique in the medium term for the control of symptoms of BPH in patients who are not candidates for surgery and in patients with urinary catheters, in whom catheter withdrawal is achieved in a high percentage.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for the integrity of the study:

- 2

Study conception:

- 3

Study design:

- 4

Data acquisition:

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation:

- 6

Statistical processing:

- 7

Literature search:

- 8

Drafting of the article:

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions:

- 10

Approval of the final version:

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Our thanks to the other authors who collaborated in this multicentre, multidisciplinary study, including the urologists from the departments at Hospital Virgen Macarena in Seville (Dr Jesús Castiñeira and Dr José Antonio Montaño), Hospital de Toledo (Dr Antonio Gómez), Hospital de Talavera de la Reina (Dr Pablo Gutiérrez) and Hospital de Puertollano (Dr Fernando de Castro) who, due to the rules of the journal cannot be included in the seven authors who head this manuscript, but without whose dedication in selecting patients and clinical follow-up, this study would not have been possible.

Please cite this article as: Monreal R, Robles C, Sánchez-Casado M, Ciampi JJ, López-Guerrero M, Ruíz-Salmerón RJ, et al. Embolización de arterias prostáticas en la hiperplasia benigna de la próstata en pacientes no quirúrgicos. Radiología. 2020;62:205–212.