We report the case of a 64-year-old woman who presented with pain in her right hypochondrium radiating to the thoracolumbar region, hyporexia and weight loss coursing for 2 months. The laboratory tests revealed leukocytosis with neutrophilia. The physical examination was normal.

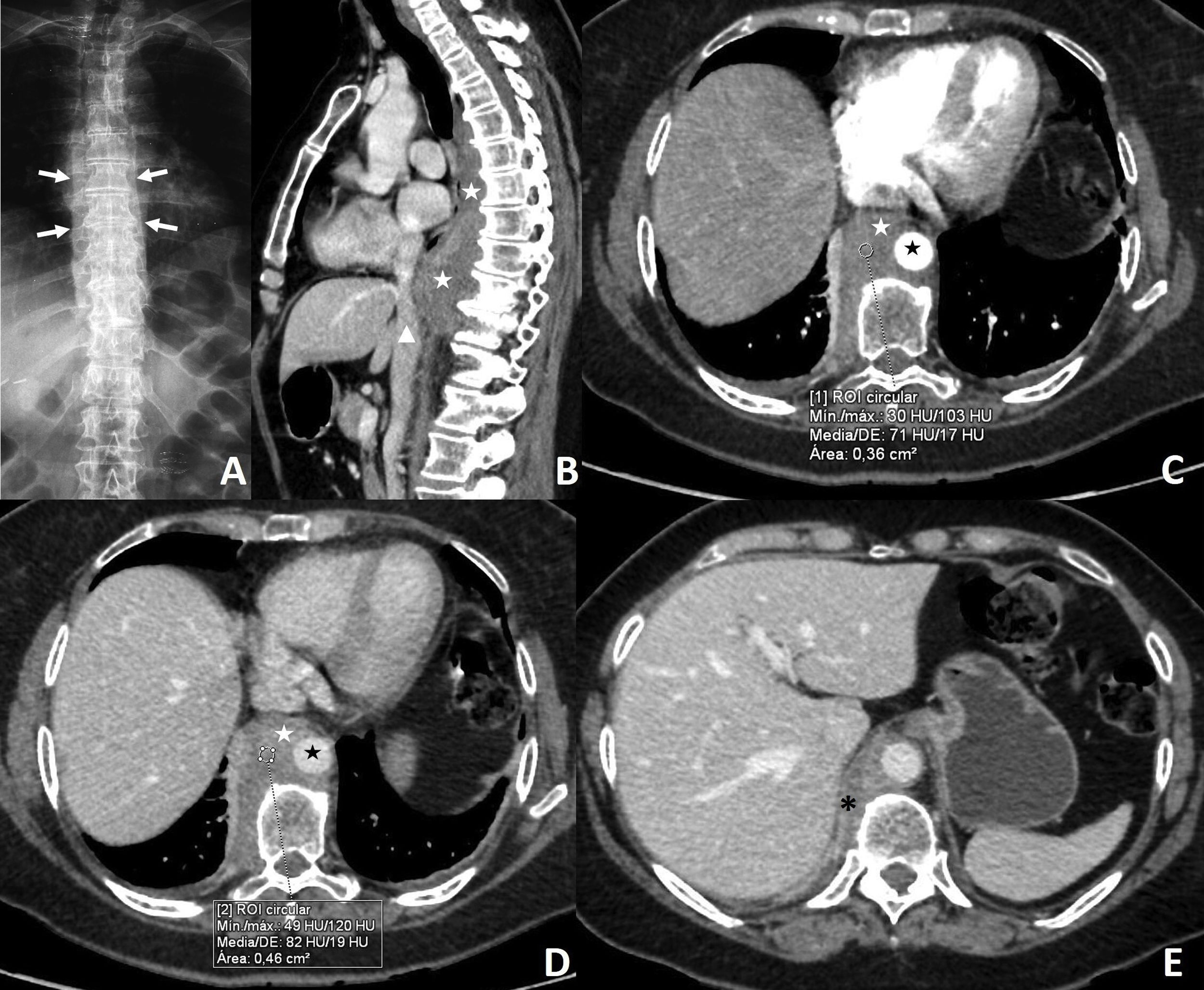

X-rays of the thoracic and lumbar spine showed widening of the paravertebral and prevertebral spaces (Fig. 1).

(A) Anteroposterior X-ray of the spine. (B) Sagittal reconstruction of multidetector computed tomography (MDCT) with intravenous contrast in the portal phase. (C–E) Axial image from MDCT with intravenous contrast in the arterial phase (C) and in the portal phase (D and E). Image A shows widening of the paravertebral spaces (white arrows). Image B reveals a soft-tissue mass in the posterior mediastinum having spread to the retrocrural space (white stars), in close contact with the inferior vena cava (arrow tip). Images C–E show the relationship of the mass (white stars) to the descending thoracic aorta (black star) and the thickening of the right crus of diaphragm (black asterisk). It shows slight, gradual enhancement.

The study was complemented with a computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis with contrast in the arterial and portal phases, revealing a soft-tissue mass in the posterior mediastinum from T4 to T10 with retrocrural spread and associated thickening of the right crus of diaphragm (Fig. 1). It showed slight, gradual enhancement with the contrast (Fig. 1). Given these findings, a lymphoproliferative or mesenchymal neoplastic origin was suspected. Extrathoracic disease was not demonstrated.

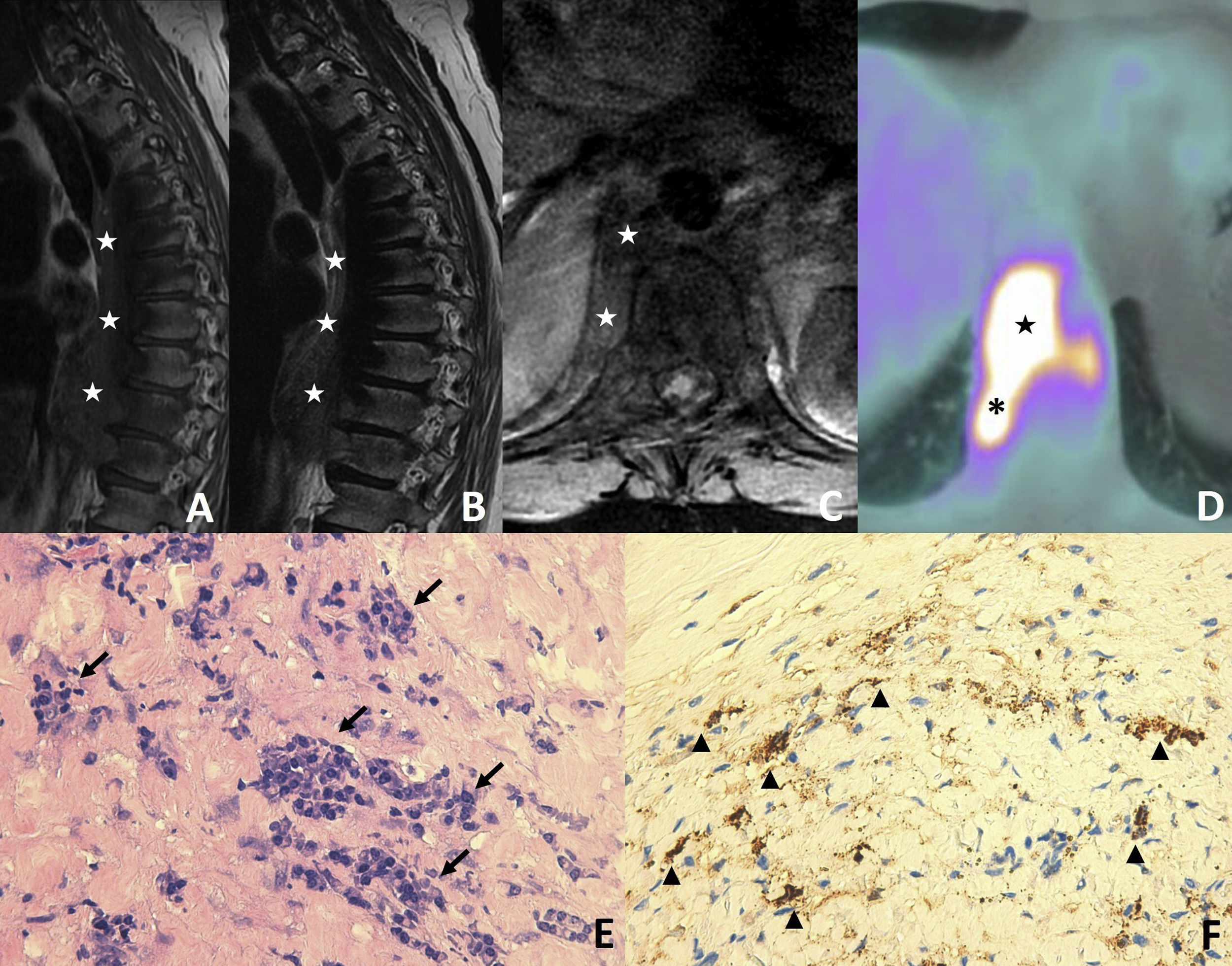

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the thoracic and lumbar spine confirmed a heterogeneous mass of intermediate intensity on T1- and T2-weighted sequences with no bone infiltration (Fig. 2). Positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET/CT) with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) demonstrated hypermetabolic activity (maximum standard unit value [SUVmax] 12.6) in the mass and right crus of diaphragm, confirming the invasion (Fig. 2).

(A–B) T1- and T2-weighted sequences of the spine on a sagittal plane. (C) T1-weighted fat-saturation (FAT-SAT) sequence on an axial plane. (D) Axial image from PET/CT with 18F-FDG. (E) and (F) Histology images with haematoxylin–eosin and staining for IgG4. Images A–C show the soft-tissue mass in the posterior mediastinum and retrocrural space (white stars). The mass has a heterogeneous nature and intermediate intensity, with no evidence of bone infiltration. Image D reveals hypermetabolic activity in the mass in the mediastinum (black star) and the right crus of diaphragm (black asterisk), consistent with infiltration. The histology images show foci of polyclonal plasmocytosis (black arrows) and the cells' positivity for IgG4 (arrow tips).

Following several CT- and bronchoscopy-guided biopsies that were inconclusive due to insufficient tissue, we resorted to biopsy with videothoracoscopy, yielding a diagnosis of chronic fibrosing mediastinitis with an IgG4/IgG ratio >40% (Fig. 2). At present, our patient is on treatment with glucocorticoids and rituximab, with partial regression of the mass.

Fibrosing mediastinitis (FM) or sclerosing mediastinitis associated with IgG4 is a diffuse subtype considered to be an idiopathic FM.1,2 It belongs to the spectrum of IgG4-related diseases, characterised by lymphoplasmocytic infiltration with a predominance of IgG4-positive plasma cells accompanied by a certain degree of fibrosis.3

It affects primarily middle-aged and elderly men.1 This multisystem disease may affect any organ; the most commonly affected organs are the pancreas, biliary tract and aorta.1,2,4

Its most common thoracic manifestation is lymphadenopathy; FM is less common.4 It may be accompanied by pulmonary nodules or masses, ground-glass opacities, interstitial or bronchovascular involvement, atelectasis or pleural thickening.2,4,5 Another sign would be Riedel thyroiditis or the fibrous variant of Hashimoto's thyroiditis.4 In 50% of cases it is associated with extrathoracic disease.4,5

FM symptoms, if present, would be compressive (cough, dyspnoea, haemoptysis and dysphagia).1,2,4

It is difficult to recognise on imaging given the limited specificity of the corresponding imaging findings. Plain X-rays usually show mediastinal widening.2 A CT scan with contrast, which is the imaging technique of choice, shows diffuse infiltration of the mediastinum by soft tissue with variable enhancement and often peribronchovascular spread. There may be associated pulmonary or pleural abnormalities.4 If thyroiditis is present, focal or diffuse hypodense areas will be visualised.4

MRI is equivalent to CT for identifying the spread of the disease but inferior in evaluating the airways. The tissue shows intermediate intensity on T1-weighted images and variable intensity on T2-weighted images and following administration of contrast.2 These diseases are usually hyperintense in diffusion, and given their fibrotic nature they present a low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC).2 PET/CT is not systematically indicated given the variable usefulness of FDG with this technique.

The differential diagnosis encompasses non–IgG4-related diffuse FM, sclerosing lymph node cancer metastases, lymphoproliferative conditions, sarcomas and extramedullary haematopoiesis.2

Its definitive diagnosis constitutes a challenge and usually requires biopsy.1,2 Initially, an imaging-guided biopsy is performed if the lesion is accessible, due to this procedure's acknowledged efficacy.1,2 In some cases, videothoracoscopy, mediastinoscopy or even open thoracotomy may be required.2

This condition exhibits a variable, uncertain natural history.1,2 It is important to diagnose it early, as delayed treatment is associated with a significantly worse prognosis.1,4 The foundation of treatment is glucocorticoids, although a potential role for rituximab is being investigated.1,2,4,5 All other surgical and non-surgical procedures are reserved for patients with compressive symptoms.

The interesting aspects of this case are the unusual nature of the condition, the as-yet-unknown mechanism of this spectrum of IgG4-mediated diseases and the extreme complexity of the imaging diagnosis thereof.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

This review received no specific grants from public agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Informed consent was obtained from the study subjects.

The authors would like to thank Alejandro Salazar Nicolás for his contributions to this study.

Please cite this article as: Lozano Ros M, Rodríguez Rodríguez ML. Imagen de mediastinitis fibrosante asociada a IgG4. Radiología. 2021;63:531–533.