Intestinal intussusception is difficult to diagnose in adults because the symptoms are nonspecific. However, most have structural causes that require surgical treatment. This paper reviews the epidemiologic characteristics, imaging findings, and therapeutic management of intussusception in adults.

Materials and methodsThis retrospective study identified patients diagnosed with intestinal intussusception who required admission to our hospital between 2016 and 2020. Of the 73 cases identified, 6 were excluded due to coding errors and 46 were excluded because the patients were aged <16 years. Thus, 21 cases in adults (mean age, 57 years) were analyzed.

ResultsThe most common clinical manifestation was abdominal pain, reported in 8 (38%) cases. In CT studies, the target sign yielded 100% sensitivity. The most common site of intussusception was the ileocecal region, reported in 8 (38%) patients. A structural cause was identified in 18 (85.7%) patients, and 17 (81%) patients required surgery. The pathology findings were concordant with the CT findings in 94.1% of cases; tumours were the most frequent cause (6 (35.3%) benign and 9 (64.7%) malignant).

ConclusionsCT is the first-choice test for the diagnosis of intussusception and plays a crucial role in determining its aetiology and therapeutic management.

Las invaginaciones intestinales en adultos son de difícil diagnóstico debido a la inespecificidad de los síntomas. Sin embargo, la mayoría tienen una causa estructural que requiere tratamiento quirúrgico. El objetivo de este estudio es revisar sus características epidemiológicas, hallazgos en imagen y manejo terapéutico.

Materiales y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de las invaginaciones intestinales que precisaron ingreso hospitalario diagnosticadas en nuestro hospital entre 2016 y 2020. De un total de 73 casos fueron excluidos errores de codificación (n = 6) y pacientes menores de 16 años (n = 46), resultando 21 invaginaciones en adultos.

ResultadosLa edad media fue de 57 años, y el dolor abdominal fue la manifestación clínica más frecuente en el 38% de los casos (n = 8). El diagnóstico mediante tomografía computarizada (TC), con la presencia “del signo de la diana”, alcanzó una sensibilidad del 100%, siendo la región ileocecal la localización más frecuente en un 38% de los pacientes (n = 8). Un 85,7% de los casos (n = 18) tenían una causa estructural y el 81% (n = 17) requirió cirugía. Los resultados anatomopatológicos fueron concordantes con la TC en un 94,1%, siendo la etiología más frecuente la neoplásica: 35,3% benignas (n = 6) y 64,7% malignas (n = 9).

ConclusionesLa TC es la prueba de elección en el diagnóstico de las invaginaciones intestinales y resulta determinante a la hora de identificar la etiología y decidir el manejo terapéutico.

Unlike in children, intussusceptions in adults are rare with nonspecific symptoms1–3, which poses a diagnostic challenge.

Classically, they were diagnosed during surgery4. The development and wider use of imaging tests enable them to be diagnosed pre-surgery and identify their aetiology and possible complications.

This work aims to review the epidemiological and radiological characteristics of adult intussusceptions treated in our centre and their influence on therapeutic management.

Material and methodsAfter approval by our centre's ethics committee, cases of intussusception that required hospitalisation between 2016 and 2020 were retrospectively analysed. Of 73 cases, coding errors (n = 6), as well as patients under 16 years of age (n = 46), were excluded, resulting in 21 intussusceptions in adults (n = 21).

Supervised by radiologists with more than five years of experience in abdominal radiology, residents of the specialty reviewed the patients' records, collecting epidemiological and clinical information, including the main symptoms. Imaging studies were evaluated, with radiologists looking for typical intussusception findings defined by the presence of the "bull's-eye" or "doughnut" sign, the "sausage'' sign or the "pseudokidney'' sign. The location of the intussusception, its aetiology, treatment and radiopathological concordance were recorded, and the presence of complications, such as pneumoperitoneum, intestinal obstruction, ischaemia and collections, was assessed.

Results67 patients with intussusception were admitted, 68.7% (n = 46) of whom were under 16 years of age, so were excluded from the study. 31.3% (n = 21), were adults. The characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table of results obtained in the study.

| A | S | Signs and symptoms | Radiology | Ultrasound | CT | Colonoscopy | Location | Treatment | Cause | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sign | Cause | Complications | |||||||||

| 73 | F | Abdominal pain | (-) | (-) | BES/SS | Lipoma | (-) | (-) | Ascending colon | Scheduled surgeryIleocaecal resection | Lipoma |

| 39 | M | Abdominal pain | O(small intestine) | (-) | BES/SS | Lipoma | O | (-) | Ileocaecal | Urgent surgeryIleocaecal resection | Lipoma |

| 54 | F | Abdominal pain | (-) | (-) | BES/SS | Mucocele | O | (-) | Ileocaecal | Urgent surgeryIleocaecal resection | Appendiceal mucocele |

| 59 | M | Abdominal pain | CS | O | BES | (-) | O | (-) | Jejunum | Conservative | (-) Idiopathic |

| 37 | F | Abdominal pain | (-) | (-) | BES (MRI) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Jejunum | Conservative | (-) Idiopathic |

| 82 | M | Abdominal pain | N | (-) | BES | (-) | SO | (-) | Ileum | Scheduled surgeryIleocaecal resection | Crohn's Disease |

| 77 | F | Abdominal pain | (-) | PKS | BES | Neo | (-) | Yes | Ileocaecal | Scheduled surgeryRight hemicolectomy | Caecal adenocarcinoma |

| 16 | M | Abdominal pain | (-) | BES/Adp | (-) | (-) | (-) | (-) | Ileocaecal | Saline enema | Mesenteric lymphadenitis |

| 46 | F | Intestinal obstruction | O(small intestine) | (-) | BES | Neo | O | (-) | Ileocaecal | Urgent surgeryIleocaecal resection | Ileal adenocarcinoma |

| 47 | M | Intestinal obstruction | O(small intestine) | (-) | BES/SS | (-) | O | (-) | Ileocaecal | Urgent surgeryIleocaecal resection | (-) Idiopathic |

| 44 | F | Intestinal obstruction | O(small intestine) | (-) | BES/SS | Lipoma | O | (-) | Ileocaecal | Urgent surgeryIleocaecal resection | Lipoma |

| 70 | M | Intestinal obstruction | (-) | O | BES | Neo | O | (-) | Transverse colon | Urgent surgerySubtotal colectomy | Adenocarcinoma |

| 34 | F | Mass effect | N | BES/Mass | BES/SS | Lipoma | (-) | (-) | Transverse colon | Urgent surgeryIleocaecal resection | Lipoma |

| 73 | F | Mass effect | N | BES/PKS/Mass | BES/SS | Neo | (-) | (-) | Ileocaecal | Scheduled surgeryRight hemicolectomy | Appendiceal cystadenoma |

| 61 | F | Anaemia | N | (-) | BES/SS | Neo | SO | (-) | Jejunum | Scheduled surgeryJejunal resection | GIST |

| 44 | M | Melaena | O(transverse) | (-) | BES/SS/PKS | Lipoma | O | Yes | Transverse colon | Scheduled surgeryRight hemicolectomy | Lipoma |

| 71 | F | General syndrome | (-) | Mass | BES | Neo | O | (-) | Sigmoid colon | Palliative | Adenocarcinoma |

| 89 | F | General syndrome | N | (-) | BES | Neo | (-) | Yes | Ascending colon | Scheduled surgeryRight hemicolectomy | Adenocarcinoma |

| 79 | F | Asymptomatic | (-) | BES | BES | Lipoma | (-) | (-) | Ileocaecal | Scheduled surgeryIleocaecal resection | Lipoma |

| 76 | M | Asymptomatic | (-) | (-) | BES/SS | Mass | (-) | Yes | Sigmoid colon | Scheduled surgeryLeft hemicolectomy | Adenocarcinoma |

| 83 | M | Asymptomatic | (-) | (-) | BES/SS | Neo | (-) | (-) | Transverse colon | Scheduled surgerySegmental colectomy | Tubulovillous adenoma |

(-): not conducted; A: age; Adp: adenopathies; BES: "bull's-eye sign''; CS: "crescent sign''; F: female; M: male; N: normal; O: obstruction; PKS: "pseudokidney sign''; S: sex; SO: sub-occlusion; SS: "sausage sign''.

The mean age was 57 years, with minimal preference for the female sex. The most common symptom, in 38% of cases (n = 8), was abdominal pain, followed by intestinal obstruction in 19% (n = 4). Other manifestations were palpable mass, general syndrome, anaemia or gastrointestinal bleeding. 14.3% (n = 3) of patients were asymptomatic and the diagnosis was incidental.

100% of the patients were diagnosed by imaging tests. All the patients underwent computed tomography (CT), except one, who only required ultrasound due to his age and the absence of complications. CT sensitivity for the diagnosis of intussusception was 100%. 90.5% (n = 19) of patients had the "bull's-eye sign''. The "sausage'' or the "pseudokidney'' signs were evidenced in 57.9% (n = 11) and 5.3% (n = 1) cases, respectively.

Among its locations, the ileocaecal region appeared in 38.1% of cases (n = 8), followed by the transverse colon in 19.1% (n = 4) and the jejunum in 14.3% (n = 3).

80.96% (n = 17) of the intussusception cases showed an underlying cause on diagnostic CT. Of the 19.04% (n = 4) cases where causes were not identified, all in the small intestine, only one required surgery (it was secondary to Crohn's disease); the rest resolved spontaneously with conservative management. Finally, 85.7% (n = 18) of intussusceptions had an underlying cause. CT sensitivity regarding identifying it was 94.4%.

The most frequent structural lesion, in 71.4% of cases (n = 15), was neoplastic, with 35.3% of them (n = 6) benign, specifically lipomas, and the remaining 64.7%, malignant (n = 9), more commonly (n = 6) adenocarcinomas (66.7%). Treatment was surgical in 81% of patients (n = 17). This was performed urgently in 41.1% of them (n = 7), mainly due to the presence of intestinal obstruction.

Of the resected lesions (n = 17), after results from pathology, a radiopathological concordance of 94.2% with CT was confirmed (n = 16).

DiscussionIntussusception is a pathology in which a segment of the intestinal loop is telescoped into another adjacent one, which can lead to obstruction, followed by inflammation and ischaemia1,5,6. It occurs due to altered normal peristalsis of the loop, often caused by a lesion in its wall7,8.

They are typical of the paediatric population when there is usually no underlying structural cause, and therefore can be reduced by saline enemas5,6. According to the medical literature, only 5% of intussusceptions occur in adults5,9. In our study, this percentage reaches 30% of the recorded cases, although we must remember that only patients who required hospital admission were included. The increased incidence of this pathology in adults could be secondary to the ageing of the population and a greater use of imaging tests.

The mean age of presentation, according to the literature reviewed, is 50 years9,10. In our study it was slightly higher, at 57 years.

Adults, unlike children, do ls1–3; nonspecific abdominal pain is the most common main symptom, followed by intestinal obstruction or palpable mass11,12. In addition, as mentioned by the De Clerk et al. group, and as we have been able to verify, anaemia, general syndrome, or gastrointestinal bleeding can also appear due to the presence of malignant neoplastic lesions6.

Intussusceptions can be classified according to their location or their aetiology. Regarding their location, most of the published series describe the small intestine as the most common location. This is possibly due to the fact that they include a high number of transient intussusceptions, which are more common in the small intestine, mostly idiopathic and do not require medical action6. In our series, by including only patients who required hospital admission, the percentage of these intussusceptions is lower. On the other hand, as occurs in our study, intussusceptions that have a structural cause occur more frequently in the ileocaecal or ileocolic region (depending on where the lesion is located) 6. Colonic location is less common and is linked to malignant lesions and older patients13. Hanan et al. describe this location in 31% of cases14. This percentage rises to 38.1% in our sample, probably given the older average age.

Depending on their aetiology, we can classify intussusceptions as benign or malignant. In the small intestine, the cause is usually benign: Meckel’s diverticulum, adhesions or lipomas and, less frequently, lymphoid hyperplasia, hemangiomas or adenomas (Peutz-Jeghers syndrome). They can also be iatrogenic, secondary to catheter placement or gastrojejunostomy15. Among the malignant causes, metastatic disease stands out,ten above adenocarcinomas, GIST, lymphoma, leiomyosarcomas or neuroendocrine tumours. On the contrary, those in the colon structure are usually malignant, commonly secondary to adenocarcinoma. Among benign lesions, lipoma stands out, followed by GIST and adenomatous polyps15. Similarly, in our work, adenocarcinoma and lipoma are the most common aetiologies.

10% of intussusceptions, especially enteric ones, do not have an identifiable cause and are called transient. Some are idiopathic; others are secondary to infections, Crohn's disease, coeliac disease, other malabsorption syndromes, or anorexia nervosa8.

The diagnosis of intussusception in adults poses a challenge. Classically, only a third of cases were diagnosed pre-operatively4. The development of imaging techniques has modified this scenario. In our series, all patients were diagnosed before surgery.

Although plain radiography is usually the first examination, the specific intussusception findings described in the literature, such as the "crescent sign'' (gas between the intussusceptum and the intussuscipiens)16, are rare in practice. In fact, we only identified it in one of our patients (Fig. 1A). However, the radiograph may reveal complications such as pneumoperitoneum or signs of obstruction, sometimes indicating the location of the change in calibre (Fig. 1B and C).

Plain radiography. A) "Crescent sign'': radiolucent crescent of gas trapped between the wall of a loop and the intussusceptum. B) Obstruction of the small intestine: distension of the loops of the small intestine with the absence of gas in the colon. C) Obstruction of the colon: dilation of the ascending colon to the proximal transverse colon, possible location of the obstruction (circle).

Ultrasound can reveal signs of intussusception such as the "doughnut sign'', formed in cross-sections of the loop by concentric hypo- and hyperechoic bands that represent one loop within the other; or the "pseudokidney sign" in the longitudinal plane, with the hyperechoic mesentery of the intussusceptum partially surrounded by a hypoechoic band corresponding to the wall of the loops (Fig. 2). However, ultrasound has low sensitivity in the detection of complications and associated lesions and, unlike in paediatric patients, clear technical limitations derived from the body habitus of adult patients (obesity) and the presence of bloating.

Ultrasound. A) "Bull's-eye" or "doughnut" sign: concentric bands of different echogenicity, corresponding to the intussusceptum inside the intussuscipiens in axial slices. B) "Pseudokidney sign": a mass with a kidney-shaped appearance in longitudinal slices, with a hypoechoic rim and a hyperechoic centre corresponding to the mesentery of the intussusceptum.

CT is the test of choice, with a sensitivity of 58%–100%, depending on the different series reviewed5,9,17. In our series, the sensitivity of CT to diagnose intussusception was 100%. Three radiological patterns are differentiated according to evolution (Fig. 3): initially, an alternating concentric arrangement of the layers of the wall of the loops involved is initially identified, in slices axial to the intussusception, generating the "bull's-eye sign''. Occasionally eccentric fat corresponding to the mesentery of the intussusceptum is associated. As inflammation increases, the "sausage sign'' appears along its longitudinal axis, with bands of hypo- and hyperattenuation corresponding to the mesenteric fat and the intestinal wall. Finally, the "pseudokidney sign" appears, secondary to oedema, mural thickening and vascular compromise18,19.

Signs of intussusception on computed tomography A) "Bull's-eye sign", with the intussusceptum inside the proximal loop (arrow) and eccentrically-arranged fat corresponding to the mesentry of the intussusceptum (outlined area). B) "Sausage sign'', composed of alternating bands of hypo- and hyperdensity, corresponding to the walls of the loops and the fat of its oedematous mesentery. C) "Pseudokidney sign": kidney-shaped mass with a hypodense centre due to oedema and vascular compromise of the involved loops, outlined by a hyperdense enhancement line (arrowheads).

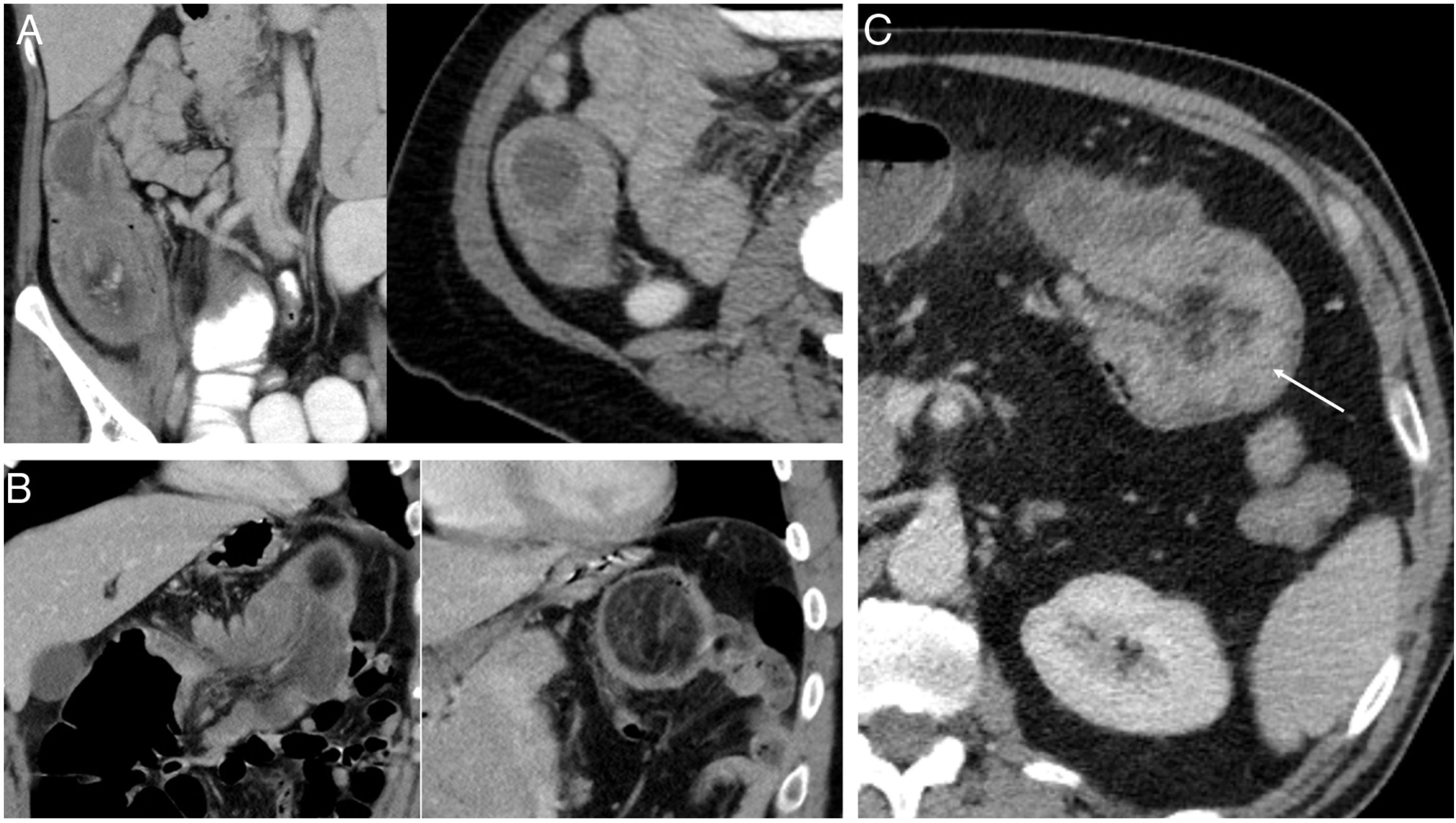

On the other hand, intussusception in adults in 90% of cases5 presents with a structural cause that we call "intussusception head''. CT often enables it to be identified, located and characterised before surgery. In our study, CT revealed the cause in 94.4% of patients (n = 17) in which it existed (Fig. 4), and the concordance between the pathology results and the diagnostic suspicion in the image reached 94.2% (n = 16).

Causes of intussusception. Ileocaecal intussusception secondary to: a cystic lesion, with a final pathological result of a mucocele (A), a well-defined lesion of fatty origin compatible with a lipoma (B), and intussusception in the transverse colon with asymmetric thickening of the intestinal wall suggestive of a neoformative process (C).

CT can also detect complications that require a change in therapeutic management, as occurred in 42.9% of our patients (n = 8), who presented with intestinal obstruction (Fig. 5), of which 75% (n = 6) required urgent surgery. Other complications described in the literature that could appear and would indicate urgent surgery, which are less common and were absent in our study, are intestinal ischaemia and/or necrosis, perforated hollow viscus or collections.

Complications of intussusceptions. Intestinal obstruction: dilatation of loops of the small intestine secondary to ileocaecal intussusception in the axial (A) and coronal (B) planes. A hypervascular lesion with a slightly necrotic centre is identified to be causing the intussusception suggestive of neoformation (arrow). The pathological result was finally ileal adenocarcinoma.

The sensitivity of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is comparable to that of CT, and the findings are similar18, but it is less accessible and dependent on the collaboration of the patient, being an option in a non-urgent context.

Colonoscopy can be a useful technique, as it allows for diagnosis and biopsy of the underlying lesion. Wang et al. proposed it to be performed pre- or intra-operatively in colonic intussusception to confirm the nature of the lesion and adapt the surgical treatment accordingly20. In our study, only 23.8% of patients underwent colonoscopy, it being reserved for doubtful cases.

Traditionally, the treatment of intussusception was surgery. The development of imaging techniques has made it possible to reduce the number of interventions, with successful conservative management in up to 82% of cases8. When it comes to short-term, enteric intussusceptions without an identifiable underlying cause, a watchful waiting attitude should be maintained since most end up resolving on their own. In patients with Crohn's disease or coeliac disease, intussusceptions do not generally require specific treatment beyond that of the underlying disease6.

If the CT reveals an organic lesion, the treatment should be surgical, and if complications are also identified, it should be urgent. The type of surgery will depend on the aetiology of the lesion and the presence of complications, hence the importance of radiological findings. If the lesion is benign and there are no signs of intestinal distress, manual reduction, followed by enterotomy and resection of the lesion, is the technique of choice (Video 1 in Supplementary material). It should be noted that surgery is also indicated in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, in whom treatment is not curative. On the other hand, the presence of signs of ischaemia or the suspicion of malignancy contraindicates manual reduction and requires en bloc resection due to the risk of perforation, anastomosis complications or tumour dissemination6. Taking into account the high incidence of malignancy in colonic intussusception, these should also be resected en bloc, as well as ileocaecal ones14, and if there are diagnostic doubts, performing a colonoscopy is recommended20.

ConclusionsIntussusceptions in adults pose a radiological challenge. CT is the technique of choice, as it allows for identification, localisation and characterisation of their structural cause, which is essential data in the therapeutic management of the patient.

AuthorshipPerson responsible for the integrity of the study: CGCS, SBG.

Study conception: CGCS, SBG, SJO, MBG.

Study design: CGCS, SBG, SJO, MBG.

Data acquisition: CGCS, SBG, MBG.

Data analysis and interpretation: CGCS, SBG, SJO, MBG.

Statistical processing: CGCS, JDGP.

Literature search: CGCS, SBG, JDGP, SSB.

Drafting of the article: CGCS, SBG, JGDP, RGF.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: CGCS, SBG, JDGP, RGF.

Approval of the final version: CGCS, SBG, SSB, RGF.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.