To analyze the values of flow obtained with an endovascular catheter, and to determine whether they are more reliable than angiographic and clinical findings for planning and for determining the outcome of invasive radiologic treatment of hemodialysis fistulas, as well as to determine the safety of this technique during interventional radiology procedures.

Material and methodsWe used endovascular catheters to measure flow in 341 vascular accesses for hemodialysis (162 [47.6%] distal fistulas, 132 [38.4%] humeral fistulas, and 47 [14%] arteriovenous grafts) in 598 procedures (a total of 3051 flow measurements). Dysfunction was most commonly due to high pressures and flow deficits.

ResultsThe catheter was used to measure the results of radiologic treatment in 419 (70%) cases and only to measure the control of flow in the hemodialysis access in 179 (30%) cases. In the cases where lesions of the access had been treated radiologically, the flow improved by a mean of 1232ml/min. In 2 (0.35%) cases, the tip of the catheter perforated the wall of the vein; this complication was resolved by inflating a low pressure balloon.

ConclusionsEndovascular catheters are useful for measuring flow in invasive vascular radiology procedures for hemodialysis. In assessing the hemodynamic status of a vascular access, they are most helpful in determining whether stenosis is present.

Analizar los valores del flujo obtenidos con un catéter endovascular y demostrar que son más fiables que los hallazgos angiográficos y clínicos para planificar y determinar el resultado del tratamiento radiológico invasivo de las fístulas de hemodiálisis, así como demostrar su seguridad durante los procedimientos intervencionistas.

Material y métodosMedimos con el catéter 341 fístulas de hemodiálisis en 598 procedimientos. En total, se hicieron 3.051 medidas de flujo. Fueron 162 fístulas distales (47,6%), 132 humerales (38,4%) y 47 injertos protésicos (14%). Los motivos de disfunción más frecuentes fueron las presiones elevadas y el déficit de flujo.

ResultadosEl catéter se utilizó para medir el resultado del tratamiento radiológico en 419 casos (70%) y solo para medir el control del flujo del acceso en 179 casos (30%). En los casos en los que se trataron radiológicamente las lesiones del acceso, el flujo mejoró en 312ml/min de media. Los casos no tratados presentaron un flujo medio de 1.232ml/min. En 2 casos (0,35%) la punta del catéter perforó la pared de la vena, que se resolvió inflando un balón a pocas atmósferas.

ConclusionesEl catéter endovascular medidor de flujos es una herramienta útil en los procedimientos invasivos de radiología vascular para hemodiálisis. Al valorar el estado hemodinámico del acceso vascular, su mayor utilidad es que ayuda a tomar la decisión de tratar o no una estenosis.

In time hemodialysis fistulas usually evolve into stenosis that diminish the flow and deteriorate the quality of dialysis.1 In the early 1990s clinical studies proved that measuring the fistula flow rate was usually prior to thrombosis.2 It could be confirmed that if stenosis could not be corrected through angioplasty the fistula ended up thrombosed.3 Later it was confirmed that not all angioplasties considered successful by the radiologist improved the flow of fistula.4 Usually a successful angioplasty in one hemodialysis fistula stenosis is determined through physical exploration and one angiography.5 However these are not objective data and in certain situation the final outcome of therapy can be tricky.6 This is why we need an instrument to establish what the flow improvement after the angioplasty really is and in order to avoid poor hemodynamic outcomes despite good angiographic outcomes.7 One system allowing us to measure flow in situ immediately after the angioplasty will provide us information on any increases objectively.7

The Doppler ultrasound is a tool used to assess the fistula flow. It is useful for the diagnosis of fistula dysfunction and fistula monitoring over time. The drawback in the vascular radiology room is that an expert in this field is needed. The flow measuring catheter-based proceeding is fast and no special set of skills to use it are needed; it is not expensive and makes the use of the angioplasty balloons needed in every proceeding profitable.6

The main goal of this study is analyzing the flow values obtained with the endovascular catheter and proving that they are more reliable than any angiographic and clinical findings in order to plan and determine the outcome of the invasive radiologic therapy of the hemodialysis fistulae. Also another goal has been to show any possible complications and the catheter safety during interventional proceedings.

Materials and methodsPatients and vascular accessesWe studied retrospectively the outcomes of the last 6 years of the flow measuring-endovascular catheter ReoCath™ Flow Catheter (Transonic Systems Inc., Ithaca, New York, USA) in 341 hemodialysis fístulae. The proceeding was explained to all patients and all gave their written informed consent, also having the approval from the hospital ethical committee. We included all dialysis fistulae that showed some kind of dysfunction based on dialytic parameters. The fistulae in which the ultrasound discarded all kinds invasive radiologic proceedings were not included. The average age of patients was 62 years of age (range: 21–88 years; 60% males). Forty-eight per cent of fistulae were distal (radial or cubital), 38% humeral fistulae and 14% prosthetic grafts made out of polytetrafluoroethylene.

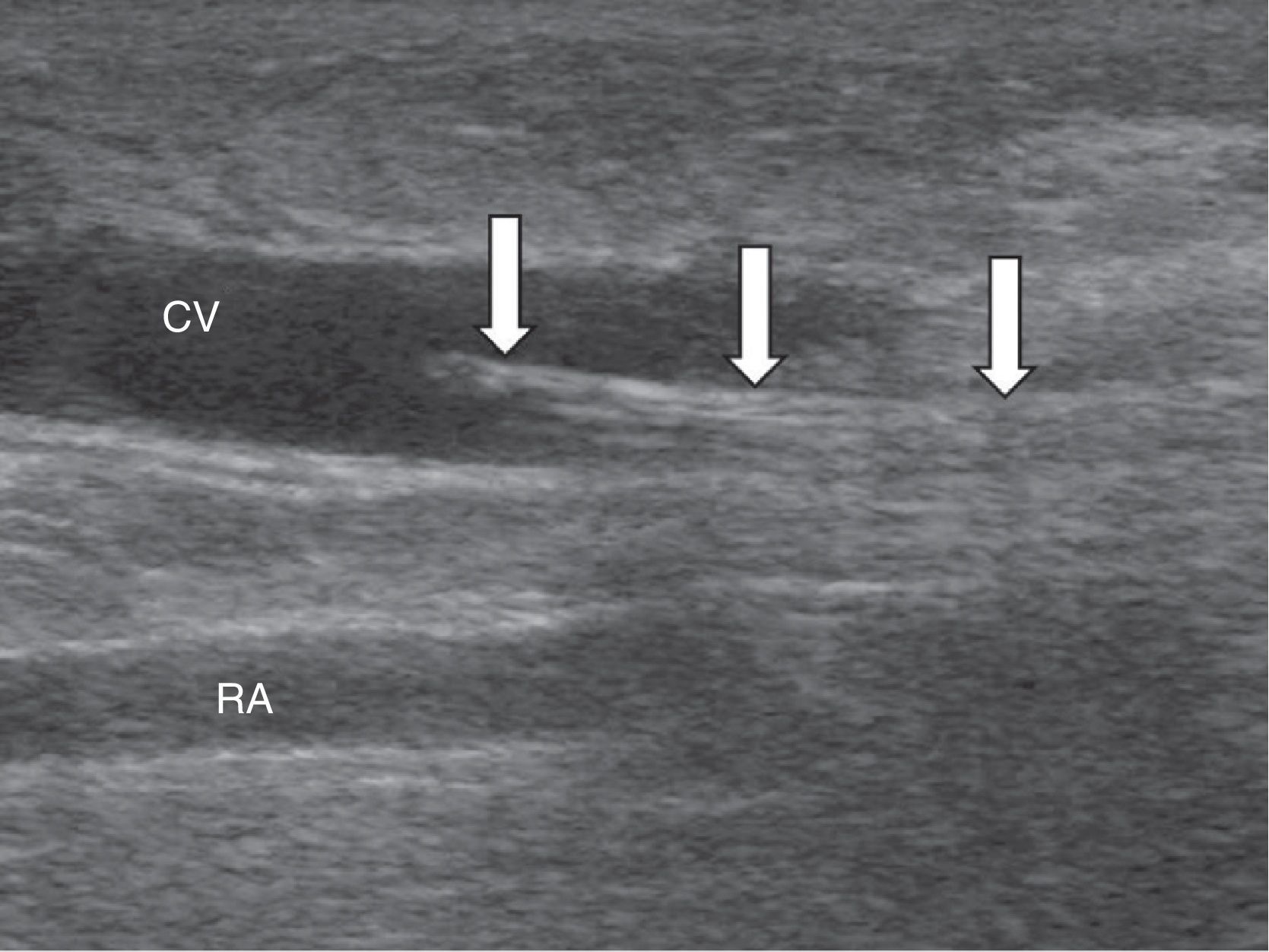

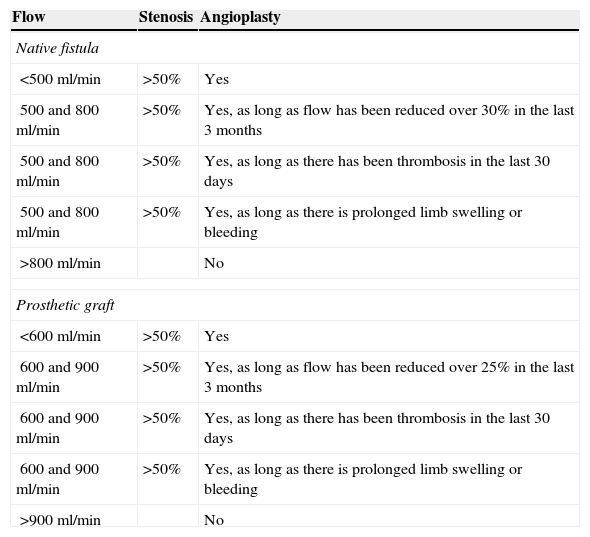

Study techniqueThe ReoCath™ Flow Catheter is a disposable catheter with an extension cord connected to one machine that measures the flow. Based on the direction of flow used for working the catheter can be antegrade or retrograde; both are 6 French caliber-catheters with a non-intense light and thus they cannot advance on the wire. Before flow measuring one fistulography is performed through retrograde approach of the artery or through vein puncture directed toward the venous anastomosis (retrograde-wise) or (antegrade-wise) in an effort to assess the whole vascular territory from the afferent artery to cardiac cavities. After diagnosis the catheter is inserted through with one introducer with the help of a fluoroscopic or ultrasound wire (Fig. 1). Then through one cord extender the catheter is connected to a screen; measurement is performed by injecting one 10ml-bolus of saline solution at room temperature. The catheter has a proximal sensor measuring the temperature of the injected saline solution and a second more distal sensor measuring thermodilution in the vascular access. The system measures blood flow through the temperature change experienced by the injected saline solution when entering the blood blow. Overall 3 measurements are taken and the average measurement is estimated. The indications of angioplasty based on flow measurements7 can be seen in Table 1.

Indications for angioplasty.

| Flow | Stenosis | Angioplasty |

|---|---|---|

| Native fistula | ||

| <500ml/min | >50% | Yes |

| 500 and 800ml/min | >50% | Yes, as long as flow has been reduced over 30% in the last 3 months |

| 500 and 800ml/min | >50% | Yes, as long as there has been thrombosis in the last 30 days |

| 500 and 800ml/min | >50% | Yes, as long as there is prolonged limb swelling or bleeding |

| >800ml/min | No | |

| Prosthetic graft | ||

| <600ml/min | >50% | Yes |

| 600 and 900ml/min | >50% | Yes, as long as flow has been reduced over 25% in the last 3 months |

| 600 and 900ml/min | >50% | Yes, as long as there has been thrombosis in the last 30 days |

| 600 and 900ml/min | >50% | Yes, as long as there is prolonged limb swelling or bleeding |

| >900ml/min | No | |

The flow measuring-catheter was used in 598 proceedings in 341 fístulae. The total of flow measurements accomplished was 3051. In 70% of cases the outcome assessment of this or that therapy was tried while in the remaining 30% no therapy was attempted. We described the practical applications of this proceeding.

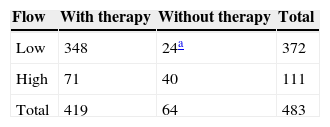

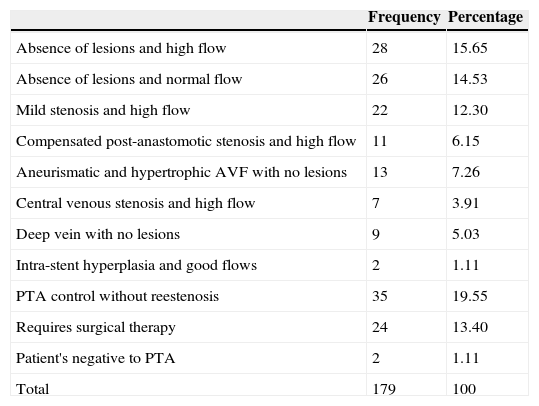

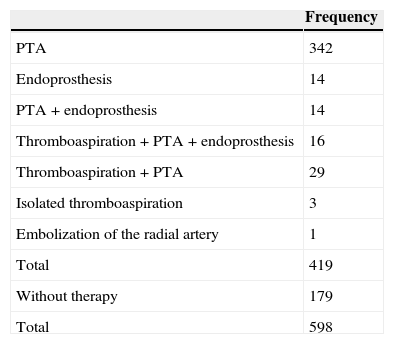

ResultsOut of the 598 cases managed in 483 (81%) were found lesions in the angiography (Table 2). Of these 419 (87%) were managed radiologically but not the remaining 64 cases that were taken to the surgeon (24 with low flows) or that were not treated to avoid triggering one steal syndrome or limb ischemia (40 with high flows). In 179 proceedings (30%) no treatment was followed (average flow found was 1232ml/min; range: 140–3.378ml/min) (Table 3). In the 419 proceedings where a treatment of some sort was followed the average flow gradient was 312ml/min (range: 60–1.443ml/min). The most common therapy was isolated angioplasty (342 cases) (Table 4 and Fig. 2). In 44 cases some kind of endoprosthesis was implanted (Fig. 3). In 48 cases manual thromboaspiration with a catheter was performed. Of the treated fistulae in 82 cases (1957%) (51 antegrade and 31 retrograde) the flow could not be measured right after therapy. Among them the machine could find the flow in 37 cases by relocating the catheter tip. In the remaining 45 cases the flow was measured in all but five cases in which flow could not be found while in the machine “error” could be read. In 2 it was due to manufacturing defects of the catheter. Of the 82 cases where we had issues measuring the flow, 65 (79.26%) were radiocephalic fistulae.

Fistulae with stenosis: correlation flow/radiologic therapy.

| Flow | With therapy | Without therapy | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | 348 | 24a | 372 |

| High | 71 | 40 | 111 |

| Total | 419 | 64 | 483 |

Abscesses non-treated radiologically.

| Frequency | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Absence of lesions and high flow | 28 | 15.65 |

| Absence of lesions and normal flow | 26 | 14.53 |

| Mild stenosis and high flow | 22 | 12.30 |

| Compensated post-anastomotic stenosis and high flow | 11 | 6.15 |

| Aneurismatic and hypertrophic AVF with no lesions | 13 | 7.26 |

| Central venous stenosis and high flow | 7 | 3.91 |

| Deep vein with no lesions | 9 | 5.03 |

| Intra-stent hyperplasia and good flows | 2 | 1.11 |

| PTA control without reestenosis | 35 | 19.55 |

| Requires surgical therapy | 24 | 13.40 |

| Patient's negative to PTA | 2 | 1.11 |

| Total | 179 | 100 |

PTA: percutaneous transluminal angioplasty; AVF: arteriovenous fistula.

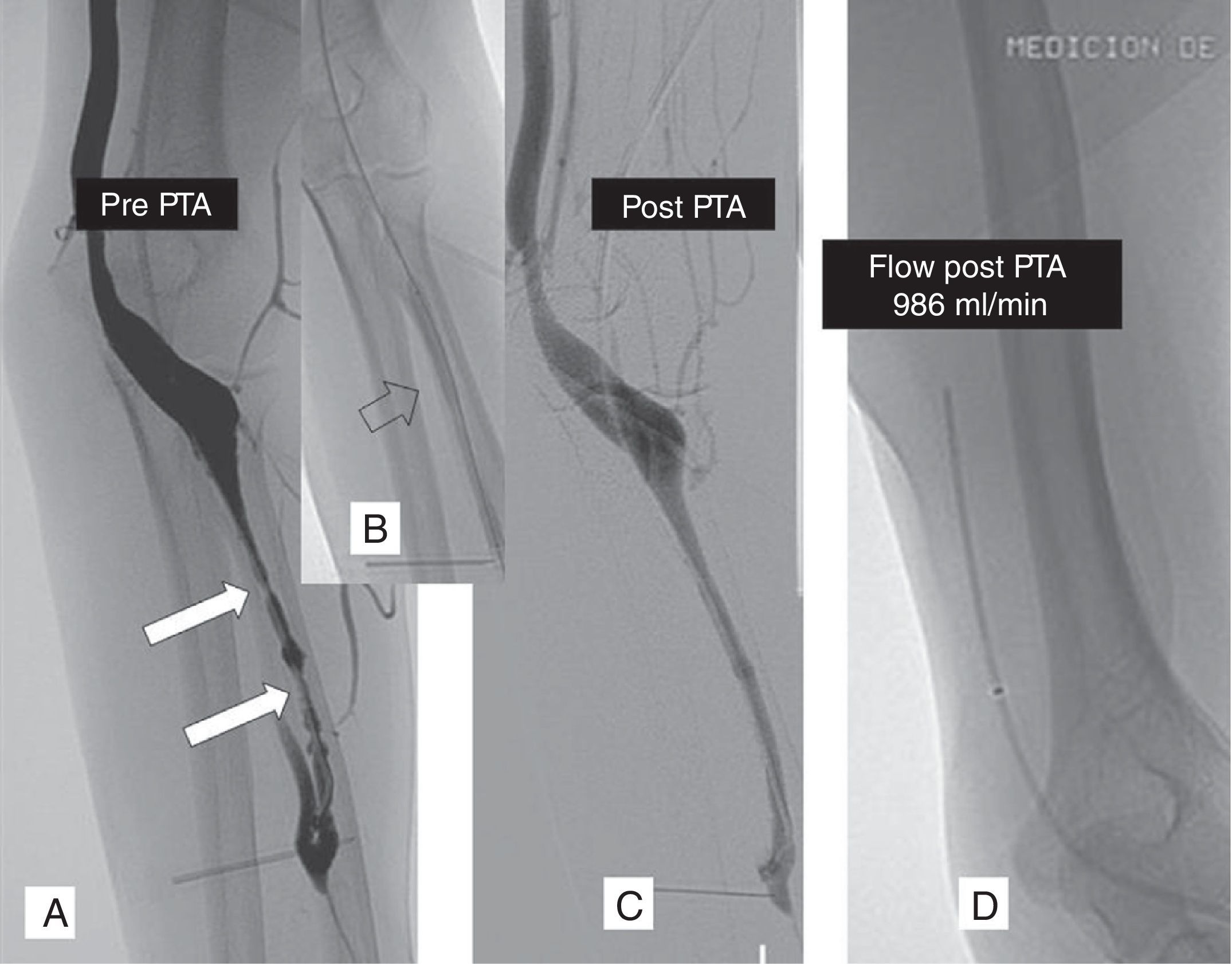

Left radiocephalic fistula with flow deficit (250ml/min). The fistulography performed through retrograde catheterization of the cephalic vein at elbow level shows stenotic lesions in the cephalic vein (A) dilated through the 7mm-diameter angioplasty-balloon (B) with a moderate angiographic outcome (C). The flow measurement taken with the antegrade catheter showed a 986ml/min final flow and this is why it was not dilated with a balloon of a wider diameter (D). PTA: percutaneous transluminal angioplasty.

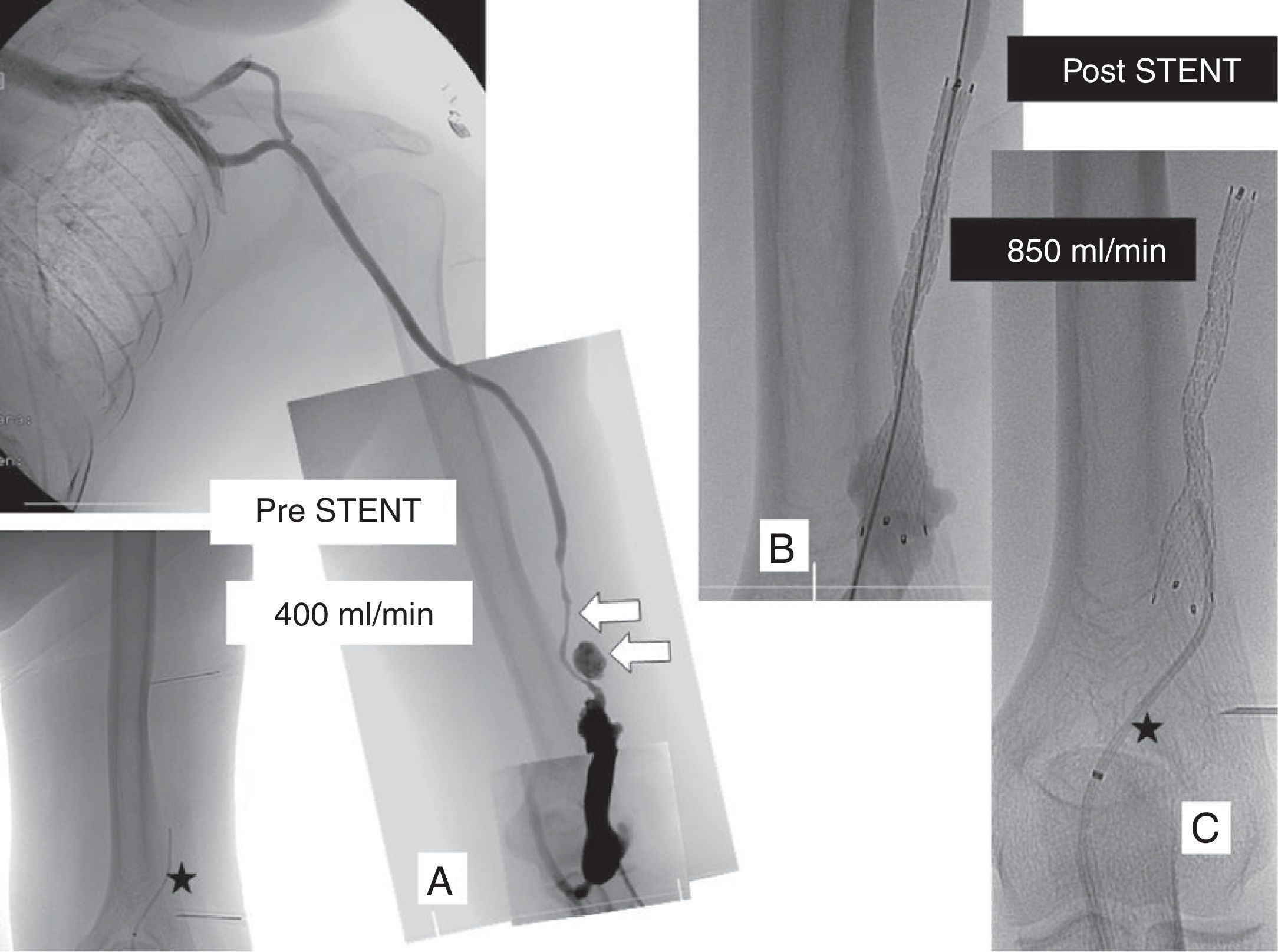

Left humero-cephalic fistula with pseudoaneurysm in puncture areas and serious stenosis (arrows). 400ml/min flow measured through the ReoCath™ antegrade catheter (asterisk) (A). One 10mm-diameter-by-8cm-diameter long “Fluency” covered-prosthesis was implanted (Bard de España, Barcelona, Spain) (B). The flow measurement taken with antegrade catheter showed one 850ml/min final flow (C).

In 2 cases (0.35%) the catheter tip drilled the vein. One of the cases–one aneurysmatic and tortuous humero-cephalic arteriovenous fistula–evolved into a hematoma that was later controlled through external manual compression. In the second case, one radiocephalic arteriovenous fistula with a retrograde catheter the tip was advanced through one collateral of the wrist at the level of one post-anastomotic stenosis and later resolved by inflating one 6mm-diameter balloon at an inflation pressure of 2atm for 3min.

The detection of high flows (>800 in native fistulae and 900 in prosthetic grafts) warned nephrologists and recommended cardiologic controls due to the risk of cardiac overload. When high flow-stenoses were found they were not dilated with one angioplasty balloon due to the risk of flow increase and because it could trigger ischemia due to vascular steal or cardiac overload. This is a major issue in humeral fistulae not as serious in the distal ones.8 One stenosis can be a “compensatory” stenosis by reducing the flow when such flow is high. The measurement of flow will avoid the dilation of the “compensatory” stenosis. When there was no indication of angioplasty, for example, in the case of juxta-anastomotic stenoses in radial fistulae the measurement of flow warned the surgeon that the new anastomosis could not be wide since there was enough flow due to the risk of turning it into a high flow-fistula.

On occasion the measures did not show the real clinical and angiographic outcome of radiologic therapy. This happened in the bail-out of thrombosed fistulae when both after the manual thromboaspiration and the angioplasty of lesions the 2 thick introducers (up to 9 French) and the security guide-wires in the lumen of the fistula altered the measurements. In these cases one of the introducers and the security guide-wires had to be removed to be able to better measure again the flow when the vascular lumen was a little more free. The same thing happened in cases in which after one satisfactory angioplasty one spasm located at the entrance of the introducer acting like a stenosis would not show the improvement of flow. In these cases puncture was performed anti-clock wise and then the spasm was dilated with one angioplasty balloon at 2 or 3atm of pressure. Something similar happened with elastic recoiling that had to be managed too. When flow would not improve after the angioplasty and no spasm or elastic recoiling could be found we had to think of lesions of the fistula artery or impaired cardiac output.9

DiscussionUsually the palpation of the fistula after radiologic therapy gives us a subjective idea of success.5 In our study we would like to suggest that measuring the flow before and after the angioplasty is way more objective than physical examination. Also our outcomes allowed us to determine in what cases the angioplasty needs to be performed and when we should end the therapy.

The international standards8–11 recommend the assessment of the outcome of the proceeding after the angioplasty of one dialysis fistula based on the residual stenosis (<30%) only and the trans-stenotic pressure gradient.12 However these 2 measurements assess only the lesion treated and give no hemodynamic information of the circuit after therapy. As a matter of fact the angiographic criteria used to assess the success of one angioplasty do not predict changes in the flow of vascular access.5,8,12,13 On several occasions it is common to overestimate the degree of stenosis before the angioplasty and the technical success based on the degree of residual stenosis.14 On the contrary the dialysis fistula flow gives us hemodynamic information that better reflects its functioning.15–17 Flow measurement values quantitatively the entire fistula including the donor artery, the anastomosis and the venous bed distal to the lesion being treated.18 Also the catheter compares flow values before and after therapy, gives a real measurement of the outcome, is being able to decide if a different balloon with a wider diameter is necessary, investigates misdiagnosed lesions (if no flow improvement has been confirmed) or regards the proceeding as finished.

Even though we did not do a study based on financial cost-effectiveness we believe that saving in angioplasty catheters when flow measurements or the increase of access patency do not be recommend it (high flow fistulae) and when access thrombosis should be avoided after finding lesions that would otherwise be misdiagnosed would compensate the cost of the ReoCath™ catheter in the short and mid term.

In daily routine one of the main objections to the ReoCath™ catheter is that it does not advance on the guide wire, thus leading to risk of vein perforations. In the 598 sessions in which we used it, we only experienced 2 perforations, that is, 0.35%. Such a low figure is possible due to all precautionary measures taken while handling the catheter, thanks to the use of road mapping or ultrasound guiding while making the catheter advance on the wire. Nevertheless one future design of a catheter over the guide wire could bring more safety to those vascular radiologists who are not very experienced using it.

Correlating the flow measurement with ReoCath™ with the Doppler ultrasound during proceedings in the same vascular radiology room is not easy to accomplish. We believe that the method of ultrasound dilution of the ReoCath™ catheter is more reliable than the ultrasound since it is not subject to the operator's subjectivity or the variability of the ultrasound equipment.18–20 However further studies could compare flow measurements with ultrasounds taken before and after the invasive proceeding, e.g. the double-blind ultrasound measurements taken out of the vascular radiology room.

Lastly sometimes we were limited to select cases in which we were going to use the measuring catheter without paying much attention to strict criteria of selection. These defects will help us be more accurate in the future.

In sum the ReoCath™ flow measuring catheter provides us with «quantitative» information on the functionality of the haemodialysis vascular access during the proceedings of interventional vascular radiology, assesses the success of angioplasty, increases the longevity of the access and avoids reintervention.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsAuthors confirm that no experiments have been performed on human beings or animals.

Data confidentialityAuthors confirm that in this report there are no personal data from patients.

Right to privacy and informed consentAuthors confirm that in this report there are no personal data from patients.

Conflict of interestsAuthors reported no conflicts of interests.

Thanks to Dr. Noelia Lacasa Pérez, M.D. for participating in the data mining, and Dr. Vicente García Medina, M.D. for supervising out research team.

Please cite this article as: García-Medina J. Manejo radiológico invasivo de las fístulas de hemodiálisis midiendo el flujo con un catéter endovascular. Radiología. 2015;57:150–155.