Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease is a benign, self-limiting lymphohistiocytic disorder. Although this condition is uncommon in Spain, it must be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with lymphadenopathies. Although the classical presentation of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease usually involves the cervical lymph nodes, there are also atypical presentations, such as in the case presented here in which the patient had isolated axillary involvement.

La enfermedad de Kikuchi-Fujimoto es un trastorno linfohistiocítico benigno y autolimitado que, aunque infrecuente en nuestro medio, es uno de los diagnósticos diferenciales que debemos tener en cuenta en el paciente con adenopatías. Aunque clásicamente suele afectar a los ganglios cervicales, existen formas de presentación atípicas, como es el caso que presentamos de enfermedad de Kikuchi con afectación axilar aislada.

Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease (KFD) is a rare, benign, self-limiting lymphohistiocytic disorder which predominantly affects young women and although it has been reported in all races has a higher prevalence in Asian ethnicity1–3. This disease generally presents as an acute painful cervical lymphadenopathy commonly associated with fever and a flu-like prodrome4. Its aetiology is not fully understood, although infectious and autoimmune causes have been suggested1,3. Although KFD has a good prognosis, clinically and histopathologically it mimics diseases such as lymphoma, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and certain infectious diseases, in which the clinical course and treatment are different2.

Case reportWe present the case of an 11-year-old girl, originally from China, who was seen in the clinic after developing a 2.5-cm mass in her right axilla. On examination, the mass had a hard consistency and was mobile and not adhered to deep planes. The patient was afebrile. She reported no weight loss or night sweats, although she did have conjunctivitis, rhinorrhoea and a generalised non-pruritic salmon-coloured rash. Her previous medical history included occasional polyarthralgia and neutropenia.

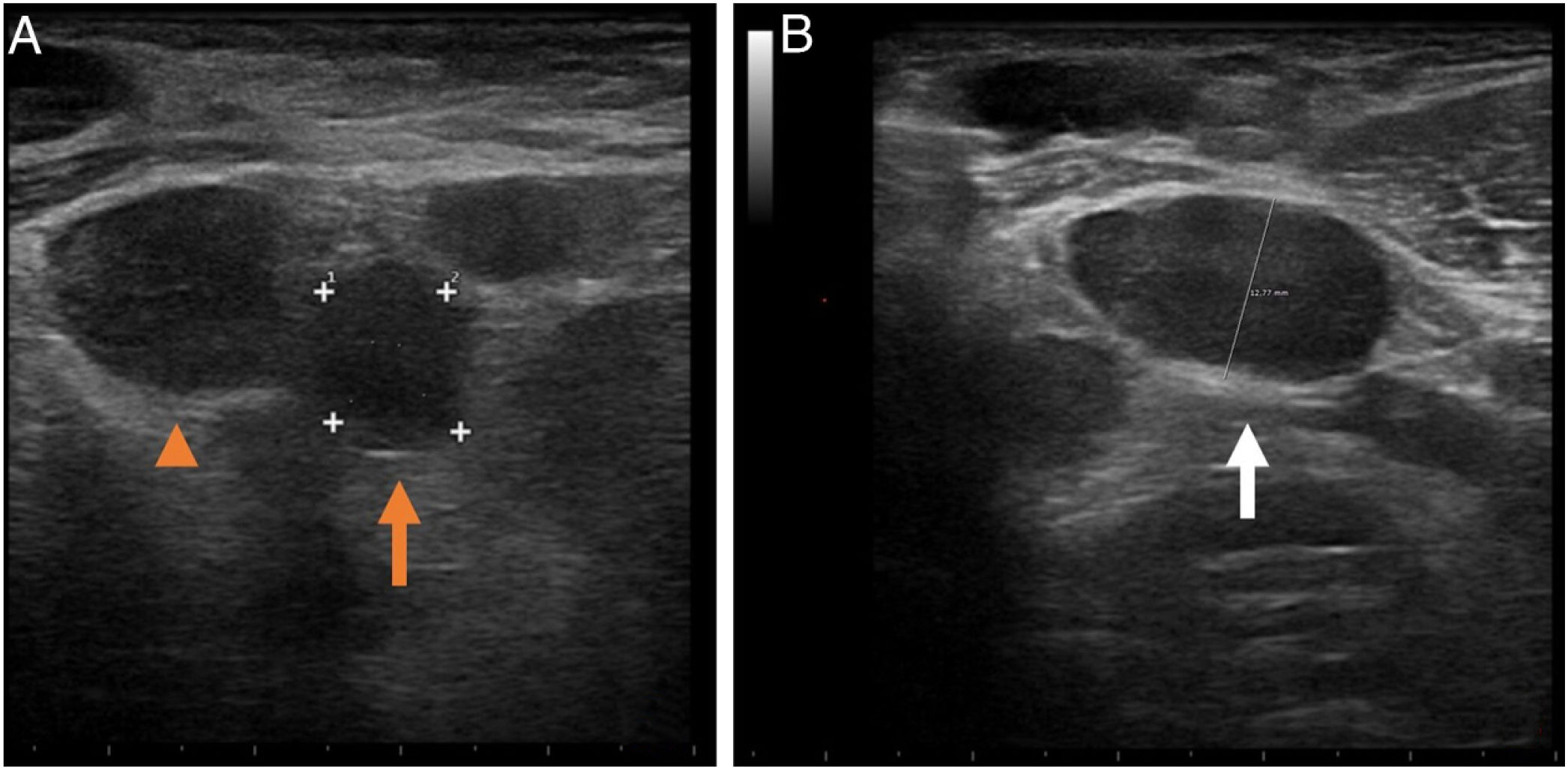

The ultrasound scan of the axillary mass showed several deeply situated enlarged lymph nodes, the largest being 14mm, with abnormal characteristics (an increased short axis), rounded in shape and loss of the fatty hilum (Fig. 1).

Right axillary ultrasound. The mass identified during the scan, about 2.5cm, actually corresponded to several enlarged lymph nodes with abnormal appearance. A) Several hypoechoic enlarged lymph nodes can be seen, some oval (arrowhead) and some rounded (arrow), none with fatty centres. They are increased in size and the short axis of the largest (arrowhead) is 14mm. B) Oval-shaped enlarged lymph node (arrow), with well-defined but irregular borders, absence of linear echogenic hilum and an increased short axis of 12mm.

Given the ultrasound findings, we decided to investigate further with blood tests, including serology, abdominal ultrasound, chest X-ray and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the lesion. In addition, we initiated empirical treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid for eight days followed by clarithromycin for seven days, without improvement.

The blood tests showed only neutropenia (absolute neutrophil count 840; normal values: 1800–8000) and fixation of IgM and IgG antibodies on the surface of the neutrophils, suggesting an immune aetiology. The immunological study revealed a slight decrease in IgA levels, an increase in IgE and low complement C4 levels (11.7mg/dl; normal values: 16−48mg/dl).

The FNA result was consistent with reactive lymphadenitis with areas of necrosis. However, as an underlying lymphoproliferative process could not be ruled out, we performed an extension study and an excisional biopsy of the lymphadenopathy.

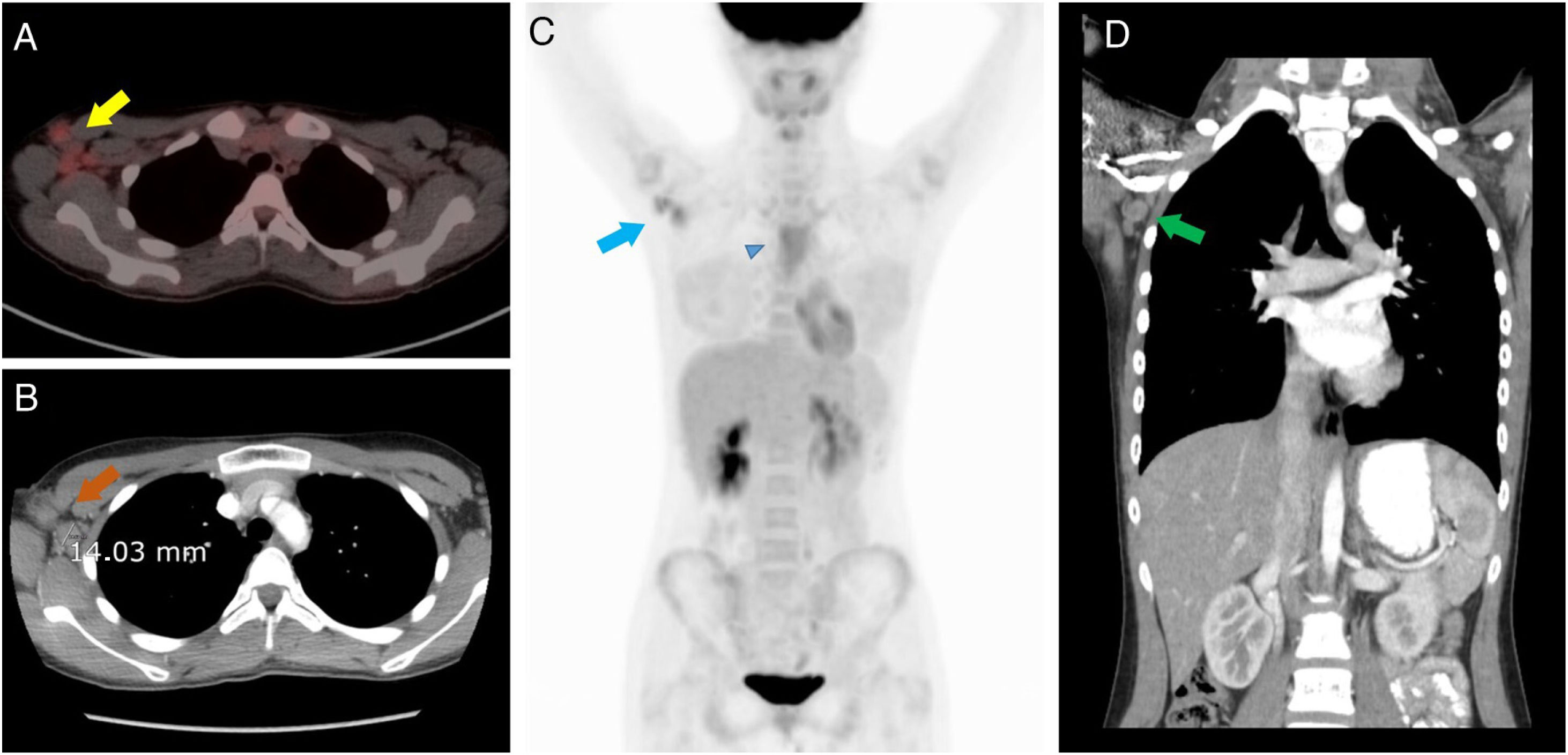

The computed tomography (CT) of neck, chest, abdomen and pelvis and positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) showed abnormal-looking lymph nodes in the right axillary region only, the largest being 14mm in diameter, with slight abnormal uptake of 18F-FDG (SUVmax=3.7), with no abnormalities in other lymph node chains (lateral cervical, mesenteric, retroperitoneal or pelvic), whereby malignancy could not be conclusively ruled out (Fig. 2).

A) Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) showing right axillary lymphadenopathy (yellow arrow) with abnormal uptake of 18F-FDG (SUVmax=3.7). B) Axial CT showing the lymphadenopathy in the right axilla (orange arrow), rounded in shape and of increased size (the largest node with short axis of 14mm). In addition, inflammatory changes can be observed in the right axilla, close to the most anterior enlarged lymph node, secondary to a recent fine-needle aspiration puncture. C) 18F-FDG PET-CT where, in addition to uptake of the lymphadenopathy in the right axilla (blue arrow), a diffuse increase in activity is observed in the soft tissues of the anterior mediastinum (blue arrowhead), probably related to thymic remnants. No lymphadenopathy can be identified in the lateral/cervical area or in other locations. D) Coronal CT scan of the chest and upper abdomen showing some of the enlarged lymph nodes in the right axilla (green arrow), with no other lymphadenopathy in either the left axilla or other locations.

Finally, examination of the resected lymphadenopathy by Pathology showed a pattern of necrotising lymphadenitis with abundant plasmacytoid dendritic cells surrounding the areas of necrosis, consistent with Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease.

With the diagnosis of KFD, the patient was prescribed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (ibuprofen 600mg), with clinical and analytical improvement at successive check-ups; no new lymphadenopathy developed in any other area and she did not require any maintenance treatment.

DiscussionWhat is particular about our case, apart from the low incidence of this disease in Europe, is the atypical presentation of the condition as isolated unilateral axillary lymphadenopathy without involvement of the lateral cervical chains.

The cervical lymph nodes are affected in 96% of cases, generally those located in the posterior cervical triangle unilaterally4, and, although uncommon, in some cases lymphadenopathy also develops in other locations (mediastinal, peritoneal and retroperitoneal)4,5. The presence of cervical lymphadenopathy has been described in cases of generalised lymphadenopathy (1–22% of cases), but frequently with bilateral involvement3–5. The nodes are usually painful (up to in 59%), firm and mobile and tend to be 2–3cm in diameter, although they can reach 6cm1,4.

Although the most common clinical manifestation is cervical lymphadenopathy, in 50% of cases it is associated with low-grade fever and flu-like prodromes, including headache, nausea, vomiting, malaise, weight loss, joint pain, myalgia, night sweats, skin rash and chest or abdominal pain1,2,4,6. Extranodal involvement in KFD is uncommon (5%-30%) and nonspecific, but may include skin manifestations which can mimic the findings of SLE1,2, bone marrow, nervous system and ophthalmological involvement, and impaired liver function2,3.

Our patient presented some of the aforementioned extranodal manifestations, including skin rash, conjunctivitis, rhinorrhoea, occasional polyarthralgia and the presence of neutropenia.

The results of a wide range of laboratory tests tend to come back normal3,4. The most common abnormal laboratory findings are mild granulocytopenia and increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels1.

The different imaging tests confirm the presence of enlarged lymph nodes, but without pathognomonic features and therefore do not specifically confirm the diagnosis of Kikuchi disease1. The definitive study for KFD is the pathology examination; an excisional biopsy of the affected lymph node will usually be required1 and KFD is characterised by histiocytic necrotising lymphadenitis in the lymph nodes7. It is important to rule out other disorders such as SLE, lymphoma and other infectious (tuberculosis, syphilis, sarcoidosis, etc) and autoimmune diseases6, as the pathological and clinical characteristics are very similar to KFD but their course and treatment is very different2.

A strong association has been found between KFD and SLE1,2. However, our patient did not present SLE at diagnosis or in the one-year follow-up period, and the biopsy and immunohistochemistry showed classic KFD features without SLE features.

In virtually all cases, the disease courses benignly and clears up in 1–3 months6. As the disease is self-limiting, symptomatic treatment measures should only be used to relieve local and systemic discomfort4,

It is important for the medical team to be aware of the possibility of KFD, particularly in a young patient with fever and lymphadenopathy (mainly cervical), since recognition of this disease will help to minimise unnecessary and perhaps more aggressive investigations, as well as inappropriate treatments.

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: SJH.

- 2

Study conception: SJH, MGV and MSGF.

- 3

Study design: SJH, MGV and MSGF.

- 4

Data collection: SJH, MGV and MSGF.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: SJH, MGV and MSGF.

- 6

Statistical processing: N/A.

- 7

Literature search: N/A.

- 8

Drafting of the article: SJH, MGV and MSGF.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: SJH, MGV and MSGF.

- 10

Approval of the final version: SJH, MGV and MSGF.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest directly or indirectly related to the contents of the manuscript.