Supplement “Pulmonary Interstitial Pathology”

More infoOrganizing pneumonia is a nonspecific pathologic pattern of response to lung damage. It can be idiopathic, or it can occur secondary to various medical processes, most commonly infections, connective tissue disease, and pharmacological toxicity.

Although there is no strict definition of the pattern of organising pneumonia as in other idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, the characteristic pattern of this disease could be considered to include patchy consolidations and ground-glass opacities in the peribronchial and subpleural areas of both lungs. Moreover, studies of the course of the disease show that these lesions respond to treatment with corticoids, migrate with or without treatment, and tend to recur when treatment is decreased or withdrawn.

Other manifestations of organising pneumonia include nodules of different sizes and shapes, solitary masses, nodules with the reverse halo sign, a perilobular pattern, and parenchymal bands.

La neumonía organizada es un patrón patológico inespecífico de respuesta al daño pulmonar que puede ser idiopático o secundario a numerosos procesos médicos, los más frecuentes, las infecciones, las enfermedades del tejido conectivo y la toxicidad farmacológica.

Aunque no existe una definición estricta del patrón de neumonía organizada como en otras neumonías intersticiales idiopáticas, se pude considerar que el patrón característico de esta enfermedad consiste en la presencia de consolidaciones pulmonares y opacidades de atenuación en vidrio deslustrado bilaterales parcheadas de distribución peribronquial y subpleural. Además, en los estudios evolutivos de la enfermedad son características la respuesta a corticoides de estas lesiones, su carácter migratorio sin o con tratamiento y su tendencia a recaer al disminuir o retirar el tratamiento.

Son también manifestaciones de la neumonía organizada los nódulos de morfología y tamaño variable, las masas solitarias, los nódulos con apariencia de «halo invertido», el patrón perilobulillar y las bandas parenquimatosas.

Organising pneumonia (OP), formerly known as bronchiolitis obliterans organising pneumonia,1 is a non-specific pathological pattern of lung response to different medical processes, such as infections, connective tissue diseases, drug toxicity, and radiotherapy, among others, which are detailed in Table 1.2–13 In its idiopathic form, cryptogenic organising pneumonia (COP) is included in the idiopathic interstitial pneumonia classification.3,4 Furthermore, OP may represent the histological pattern present in exacerbations of other interstitial pneumonias, especially in usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP).14

Causes of organising pneumonia.

| Infection (bacterial, viral, parasitic, fungal) |

| Drugs (immunotherapy, amiodarone, nitrofurantoin, methotrexate, etc.) |

| Collagen disease |

| Associated with other interstitial diseases (eosinophilic pneumonia, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, usual interstitial pneumonia, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia) |

| Haematologic malignancies (leukaemia, lymphoma) |

| Transplant (lung, liver, bone marrow) |

| Radiotherapy |

| Common variable immunodeficiency |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's, ulcerative colitis) |

| Aspiration |

| Inhalation |

| Reaction to pulmonary processes (abscess, neoplasm, alveolar haemorrhage, airway obstruction) |

Although it is accepted that it may be underdiagnosed, in a Spanish registry of interstitial diseases, it ranked third, after idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis,15 although its secondary form can be much more common.16

In this review, we will look over the pathological findings, the various forms of clinical and radiological presentation of OP, and its therapeutic management, with particular emphasis on radiological manifestations.

Clinical presentation, diagnosis and management of organising pneumoniaThe clinical and radiological presentation of OP can be very varied and ranges from clinical pictures indistinguishable from a pneumonic process to solitary pulmonary nodules in asymptomatic patients. The average age of patients is around 50–60 years.2 Most patients have a clinical picture characterised by non-productive cough and dyspnoea accompanied by fever and, sometimes, flu-like symptoms1 usually with subacute onset and of four to six weeks' duration,5 although it can last for months.1 It is often suspected when there is a clinico-radiological picture of pneumonia that does not respond to antibiotics. From the first descriptions of the disease, two typical characteristics stand out in its course: response to corticosteroids and the high rate of relapse when the dose is reduced or suspended.1–3,8,17 The spontaneous regression and migratory character of pulmonary lesions are also characteristic.13,18

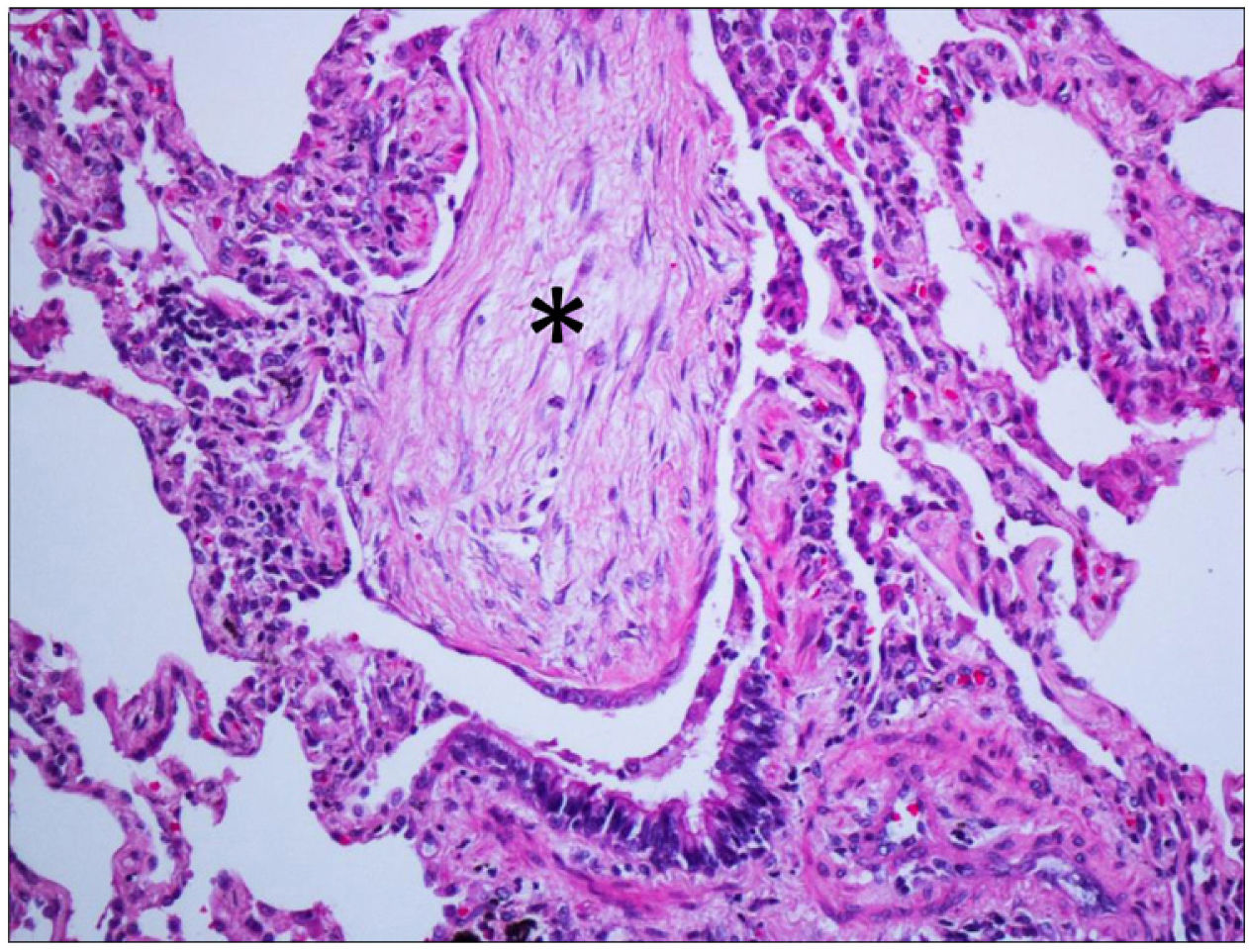

Pathophysiologically, the organisation, characterised by fibroblastic proliferation, is a frequent response to lung damage from different causes and its pathological and radiological manifestations depend on the degree of damage and the associated reparative response, adopting different patterns, such as diffuse alveolar damage, acute fibrinous and organising pneumonia and OP. The presence of hyaline membranes and fibrin “balls” in the air spaces, respectively, are the distinctive pathological features of the first two entities.19 The pathological pattern of OP is characterised by the presence of fibroblastic foci in the air space affecting alveoli, alveolar ducts and bronchioles, typically with preservation of pulmonary architecture and limited interstitial inflammation. Fibroblastic balls growing in the air spaces, called Masson bodies, are a hallmark of the disease (Fig. 1). Their presence in the bronchiolar lumen was the motivation behind the original name of “bronchiolitis obliterans OP”. Still, it was abandoned because it was confused with bronchiolitis obliterans (now called constrictive bronchiolitis). The presence of other findings, such as prominent interstitial inflammation, granulomas, peribronchiolar metaplasia, lymphoid aggregates, vasculitis, interstitial fibrosis, or honeycombing, make it necessary to consider diagnostic alternatives. It must also be taken into account that OP can appear along with neoplasms20 or granulomas19 and, occasionally, within other pathological entities, some of which represent an important clinical-radiological differential diagnosis of OP, such as eosinophilic pneumonia21 or non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), in which more than half of the cases present foci of OP.22 In fact, in a study conducted by a panel of experts,22 when the clinical-radiological data supported the suspicion of OP, this diagnosis was favoured over that of idiopathic NSIP, regardless of whether the histological pattern was of the latter. In addition, a pattern of OP overlap with NSIP is described in which there are generalised foci of OP with preservation of the lung architecture, accompanied by diffuse interstitial inflammation or fibrosis spatially distant from these organising foci.22,23

In most cases, the pathological changes of OP are completely reversible, which differentiates it from other progressive fibrosing diseases.

The diagnosis of OP can be established without the need for pathological confirmation2,24 in the presence of a compatible clinical-radiological picture, especially if any of the associated conditions are described in Table 1. Bronchoalveolar lavage can help establish the diagnosis, especially by ruling out diseases such as infections and eosinophilic pneumonia. When a biopsy is necessary, samples obtained by transbronchial and percutaneous biopsy can be diagnostic.2

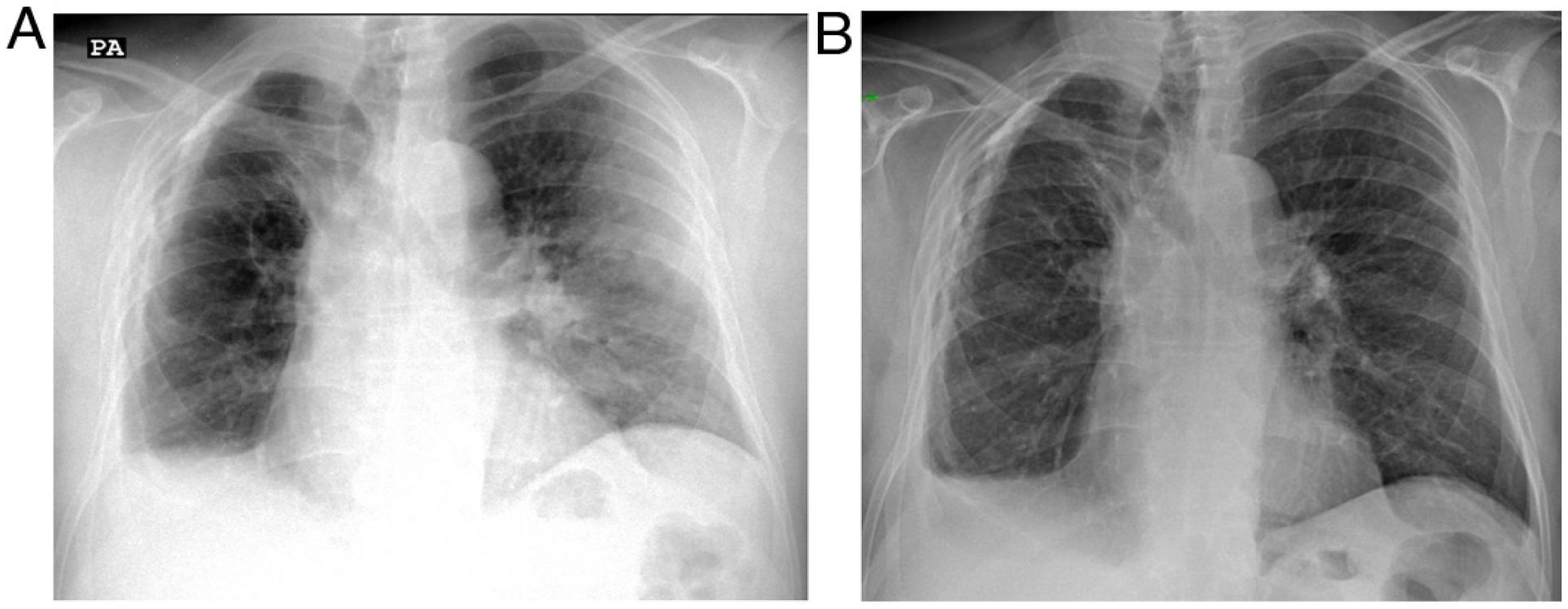

The treatment of OP is based on high-dose corticosteroids, which in most patients leads to rapid improvement of symptoms, followed by radiological resolution.2,16 Indeed, this response to treatment supports diagnostic suspicion in those cases diagnosed without histological confirmation (Fig. 2). Relapses, with the reappearance of symptoms and radiological worsening when the dose is lowered, or the corticosteroids are discontinued, can occur in up to 60% of the cases of COP,16,17 representing a datum of diagnostic value that only appears in a few diseases, such as eosinophilic pneumonia, vasculitis and alveolar haemorrhage.25

Patient with a history of organising pneumonia was seen due to a suspicious clinical picture with dry cough, dyspnoea and fever. a) The radiograph reveals a peripheral consolidation in the left lung compatible in the clinical context with organising pneumonia. On the right side, volume loss with blunting of the costophrenic angle and calcified pachypleuritis can be seen. b) One week later, after treatment with corticosteroids, the chest radiograph reveals almost complete resolution of the alterations in the left lung.

The radiological manifestations of OP, as well as the clinical ones, can be varied. However, although the OP pattern, like that of other interstitial diseases, is not as well-defined based on criteria as that of UIP, it is accepted that the pattern that can be considered characteristic of this disease consists of the presence of patchy pulmonary consolidations of peribronchial and subpleural distribution, which can occur in 60–80% of cases.4,5,25,26 In a study that assessed the diagnostic yield of computed tomography (CT) to diagnose a series of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias, COP was that which was diagnosed correctly in a greater percentage, in 79% of the cases.27 Its migratory character, sometimes even without treatment,28 and its response to corticosteroids16 would shape the "typical" radiological picture of OP. In addition, the appearance of some lesions forming curvilinear bands or in the form of a "reversed halo" and with a "perilobular pattern" are various radiological characteristics that have typically been associated with OP.29–32 Other findings, such as ground glass opacities, nodules or reticular involvement, are also manifestations of the disease, although less specific.16

Some of the radiological findings of OP will be reviewed below.

ConsolidationThis is the most characteristic finding of the disease and, along with ground glass opacities, the most frequent. About 75% of COP cases present as multifocal consolidations, usually peripheral that migrate over weeks.25

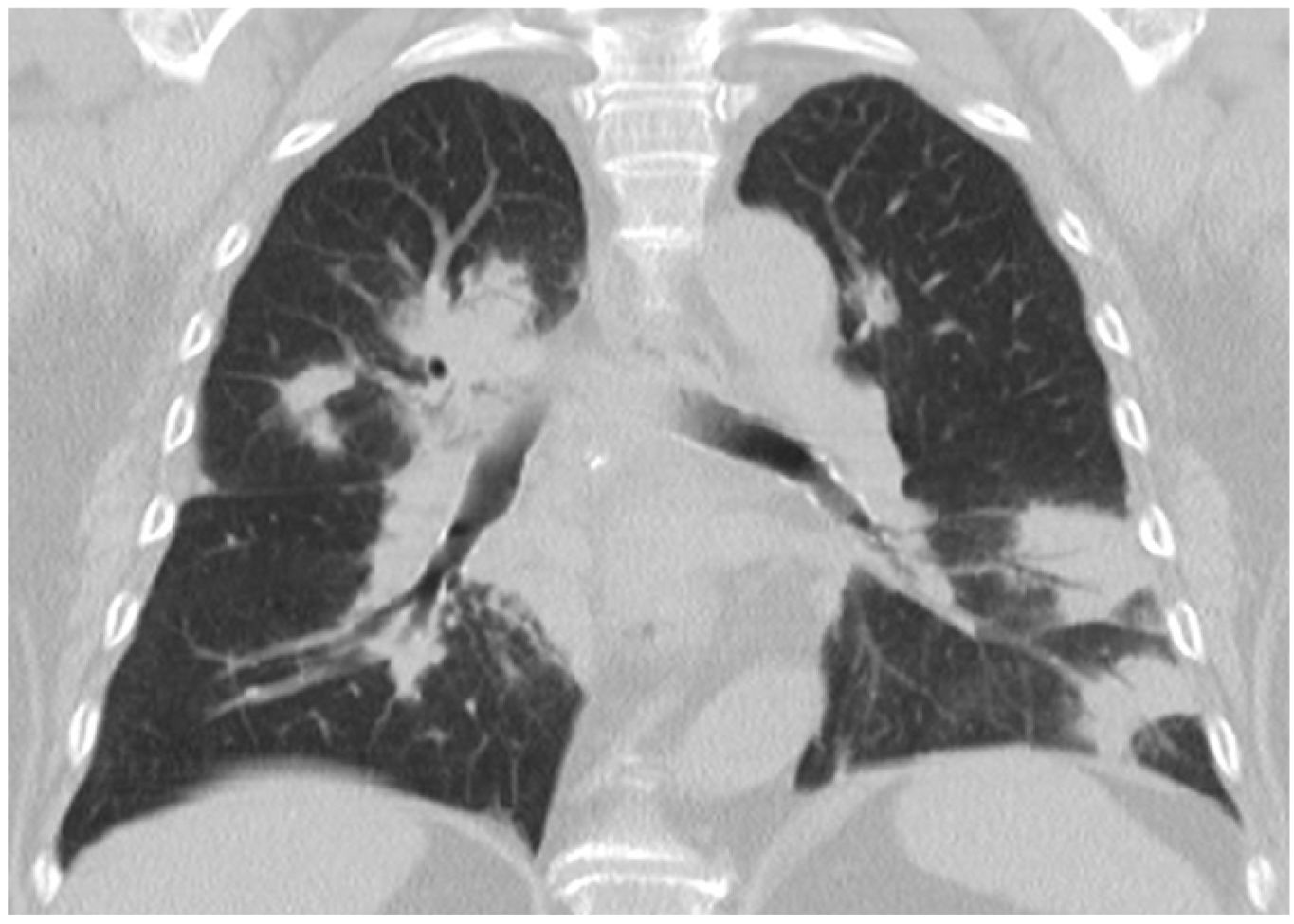

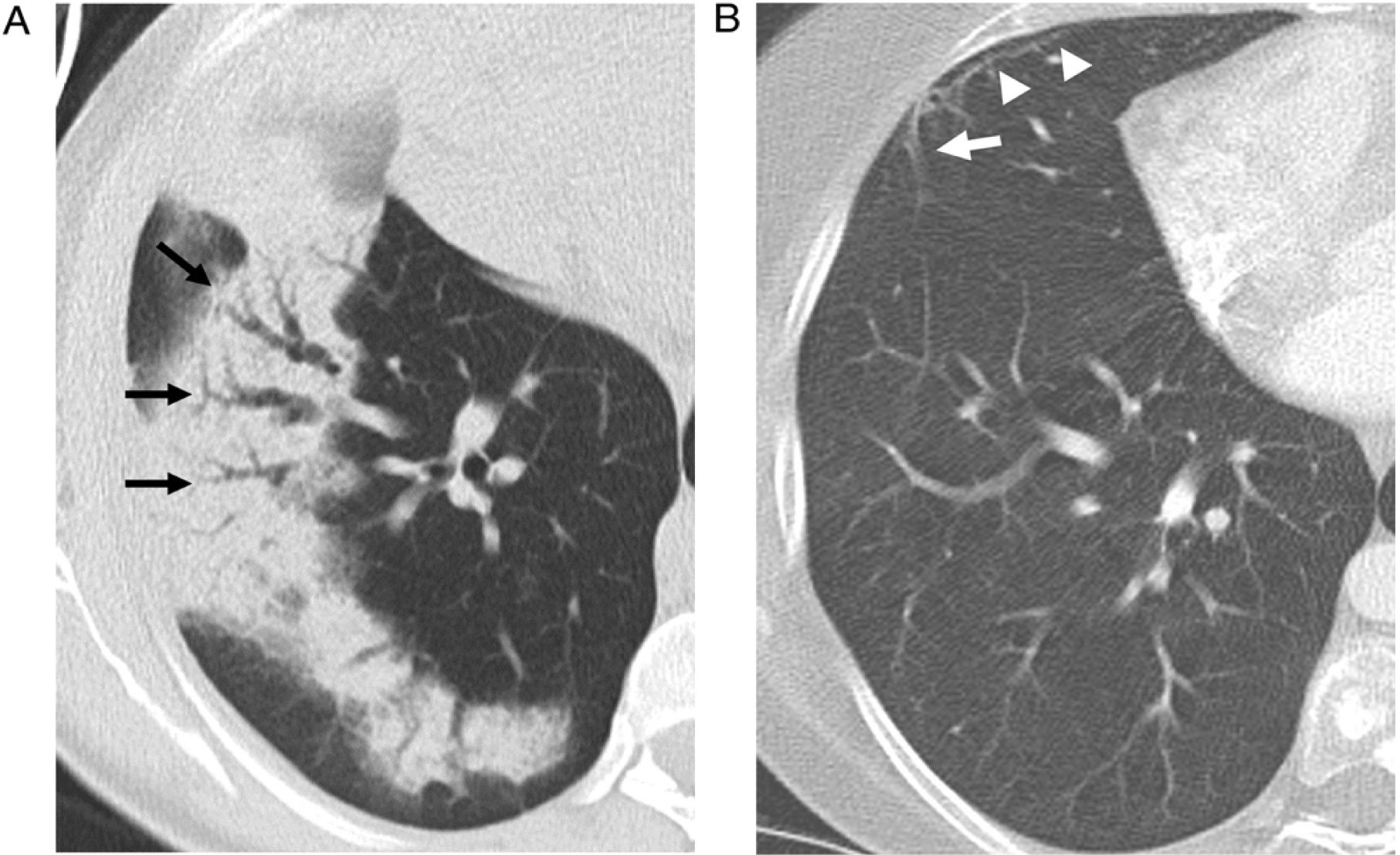

They may appear on chest radiographs as patchy bilateral opacities of variable density.1,2,33 On CT, consolidation foci are usually patchy, bilateral and asymmetric, with a tendency to show a predominantly peripheral subpleural, and sometimes peribronchovascular, distribution (Fig. 3), with a slight predominance in the lower regions of the lungs described.16,29–31,33,34 Air bronchogram is common, sometimes revealing mild bronchial dilation,31,33–36 which usually disappears with the consolidation resolution (Fig. 4).

A 51-year-old woman treated with radiotherapy six months earlier with histologically confirmed organising pneumonia. a) CT reveals consolidation in the right lower lobe with bronchial dilatations (arrows). A CT control two months later (b), after treatment, reveals complete resolution of the consolidation and normalisation of the bronchial calibre. At this time, a small parenchymal band (arrow) associated with a subpleural line (arrowheads) is visible in the middle lobe.

The presence of consolidation in the initial CT has been associated with a higher percentage of resolution of OP alterations32; however, in patients with OP secondary to collagen disease, a higher percentage of consolidation is also associated with a higher recurrence.37

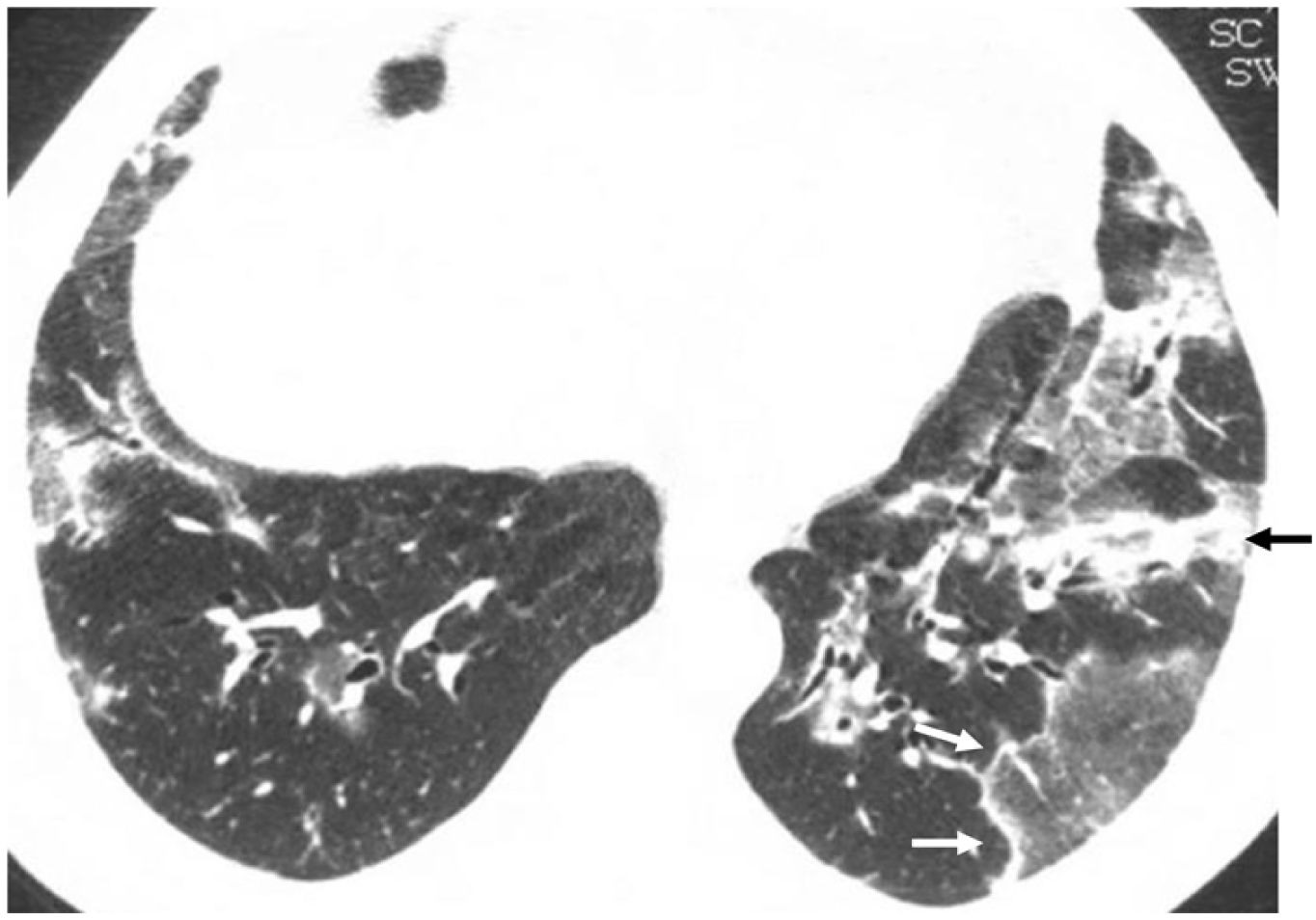

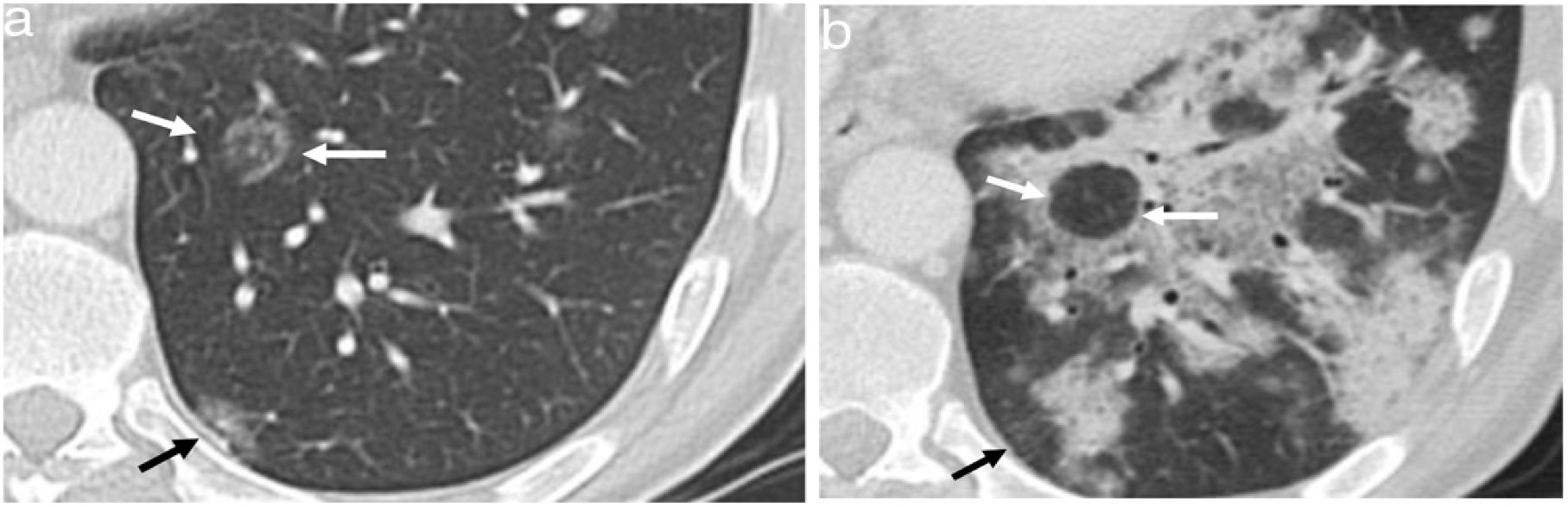

Ground-glass opacitiesIn some series, OP is the most frequent finding,16,30,38 although it is usually part of a mixed pattern in combination with consolidation16,31,33,34 (Fig. 5). Histopathologically, ground glass opacities correspond to areas of inflammation of the alveolar septa and intraalveolar cellular desquamation with small amounts of granulation tissue in the terminal air spaces.34 These opacities may appear as an evolution of consolidation foci.25,39

Relapsing cryptogenic organising pneumonia. CT slice of the lung bases showing bilateral ground-glass opacities with a reversed halo sign, with a denser outer linear area (white arrows) and an inner ground-glass area. There is also a band of peribronchial consolidation (black arrow).

The association of ground-glass opacities with septal thickening adopting a “crazy-paving” pattern is rare in OP.40

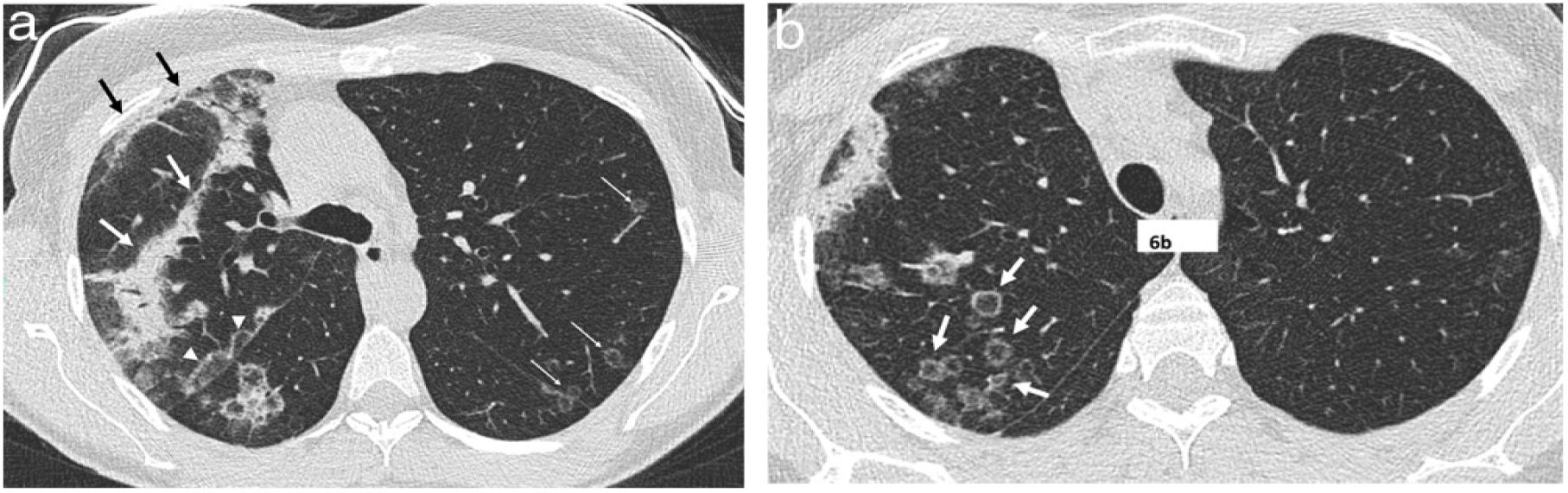

Reversed halo signThe reversed halo sign is also called the "atoll" sign41,42 or the "fairy ring" sign, although the first term is preferred.43,44 It is defined as an area of ground glass attenuation surrounded by a more or less complete halo of consolidation (Fig. 6), sometimes with a more lunate or linear morphology (Fig. 5). Pathologically, it has been explained by the presence of inflammation of the alveolar septa centrally. At the same time, the denser peripheral area corresponds to the OP with granulation tissue in the air spaces.45 Although initially described as characteristic of OP, present in 19% of cases,30 it has subsequently been described in numerous entities that include infections (including tuberculosis or mucormycosis), pulmonary infarction, vasculitis such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis, sarcoidosis, and even neoplasms such as lymphomatoid granulomatosis or neoplasms treated with radiofrequency or radiotherapy.46,47 The presence of nodularity in the halo that appears in tuberculosis has been described as differentiating the halo of COP.48 In the case of invasive fungal infections, the reversed halo has a thicker outer ring and is accompanied by reticulation inside and pleural effusion compared to OP of another aetiology.49

A 51-year-old woman with a history of right breast cancer treated with conservative surgery and radiotherapy presented with organising pneumonia six months after finishing treatment. a) Axial CT slice revealing an anterior subpleural consolidation band related to radiation pneumonitis (black arrows) and separated from it by healthy lung tissue; another band of consolidation is observed (white arrows). Also visible is a perilobular pattern in the form of a subpleural arcade next to the right major fissure (white arrowheads) and several nodules with the appearance of a reversed halo in the left lung (thin white arrows). In an upper slice (b), numerous nodular opacities with a reversed halo can be seen in the right upper lobe (arrows).

The perilobular pattern was initially described as a form of involvement of the structures that form the boundary of the secondary pulmonary lobule in relation to the interlobular septa.50,51 It is defined as the presence of poorly defined opacities with a polygonal distribution or forming arcs, which are frequently located in the periphery of the lung, next to the pleura, and surrounded by aerated lung (Figs. 6 and 7). Initially, it was described in up to 57% of patients with OP,29 always in patients who also had foci of consolidation.

Cryptogenic organising pneumonia. a) Perilobular pattern (arrows) with pulmonary opacities of variable thickness forming arches with a pleural base, surrounded by normal lung and with some consolidation foci. Control six months later (b) reveals a clear residual subpleural line in the right lower lobe (arrows).

Presentation in the form of nodules (Fig. 8a) or masses (Fig. 8b) may accompany other OP findings or be the only manifestation of the disease. They can be multiple or single, in which case it is known as focal OP52,53 and raise differential diagnosis with neoplastic lesions, especially when patients are asymptomatic, which is described in up to 38% in a series.52 Presentation as focal OP is associated with a good prognosis.23

Organising pneumonia in a patient with a history of lymphoma in remission for three years. a) Nodule in the right upper lobe with air bronchogram and slightly spiculated edges with arcuate morphology spicules towards the nodule (arrows). b) Small nodules in the right lower lobe and irregular consolidation in the left lower lobe.

The size of the nodules is variable. Smaller ones can be millimetric and ill-defined in the form of air space nodules, although they can also present as better-defined nodular lesions with smooth contours.36 Regarding larger nodules and pulmonary masses, these can exceed 5 cm and usually have irregular borders, with a polygonal morphology53 and with air bronchogram (Fig. 8 a and b), occasionally with spiculated contours and pleural tails, and sometimes accompanied by a ground glass halo.54 In our experience, the spicules sometimes show an arcuate appearance towards the nodule, unlike the tumour ones that radiate from the lesion (Fig. 8a). Occasionally they can cavitate.52,54

In one series,31 the nodular presentation was more frequent in immunosuppressed patients, in whom a differential diagnosis with invasive fungal disease can be proposed. In immunocompetent patients, on the other hand, the differential diagnosis must be established with primary multifocal pulmonary neoplasm, metastases, lymphoma and vasculitis. The presence of nodules associated with other findings acquires diagnostic value to differentiate OP from radiologically similar diseases, such as chronic eosinophilic pneumonia21 and acute interstitial pneumonia,55 where they are less frequent.

Parenchymal bands and subpleural linesLinear opacities in OP can manifest as parenchymal bands, sometimes radiating from the central lung along the bronchi, or as subpleural lines parallel to pleural surfaces.56 Most of the time, they are part of the OP findings, but sometimes they are the only manifestation or the result of the evolution of larger lesions (Fig. 4b and b).

Other radiological manifestations of organising pneumoniaReticular involvement as the predominant finding is rare.25

Although pleural effusion is infrequent in OP, some studies find it in more than 20% of COP,21 and even described in up to 60% of the secondary OP,20 possibly related to the disease-causing OP.

In a study comparing the frequency of adenopathies in a series of patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, these were less frequent in COP than in the rest of the diseases.57 However, they are found in 20–40%.30,31,53,57

Evolution of organising pneumoniaAs stated above, both a good response to corticosteroids and relapses are common in OP.1,3,8,17 Spontaneous regression without treatment can be relatively common in COP, up to more than 40% in a series of patients with bilateral lesions that had not been completely resected,16 while, in this same series, relapse upon lowering or ending corticosteroid therapy occurred in 66% of patients.

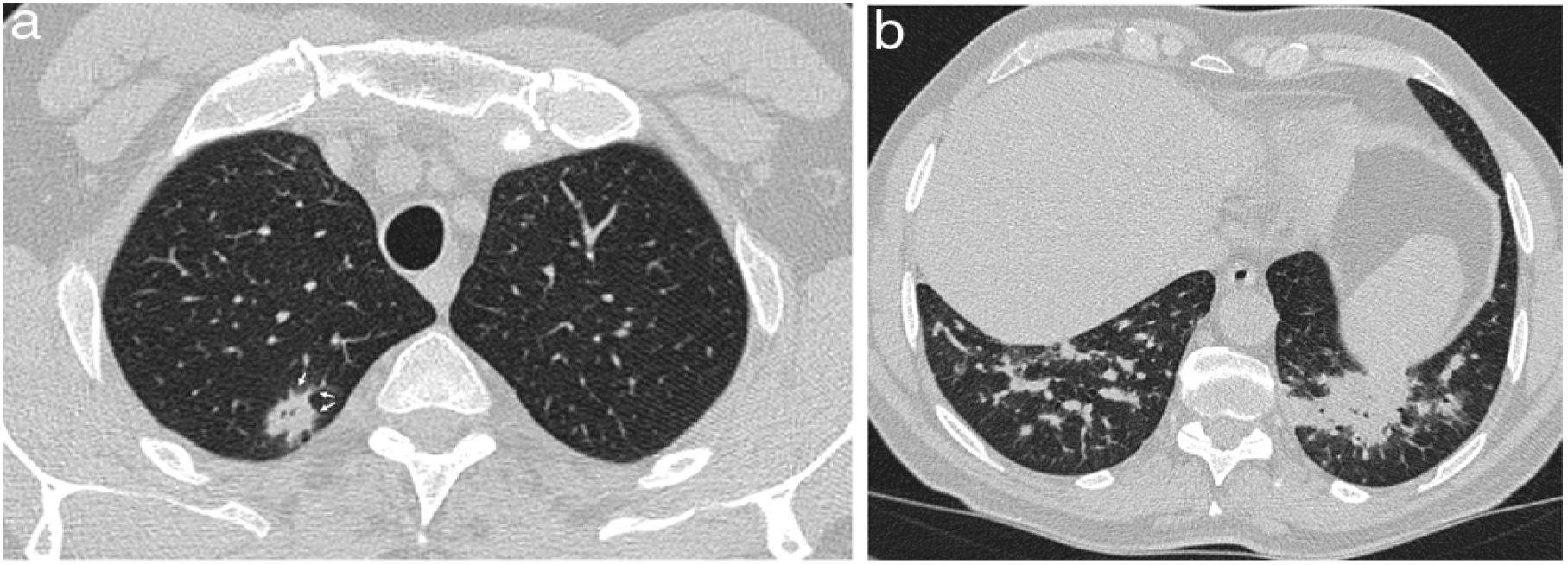

We have described a characteristic form of relapse in patients with a radiological pattern of OP called the "negative relapse sign", in which the new lesions appear on the periphery of the previously affected areas, leaving the previously affected lung as normal lung areas, in what appears to be a negative of the initial presentation (Fig. 9).58

A 53-year-old man with pulmonary neoplasm in the right upper lobe treated with radiotherapy and later with nivolumab. Six months later, he presented with dyspnoea and hypoxaemia, and CT (a) reveals a nodular opacity with a reversed halo (white arrows) and a small subpleural opacity (black arrow) in the left lower lobe. The patient was treated with corticosteroids and during dose reduction, 10 weeks after the previous CT, the symptoms reappeared. The CT (b) shows consolidation in the left lower lobe that leaves the areas where the nodular (white arrows) and subpleural (black arrow) opacity were situated “in negative”.

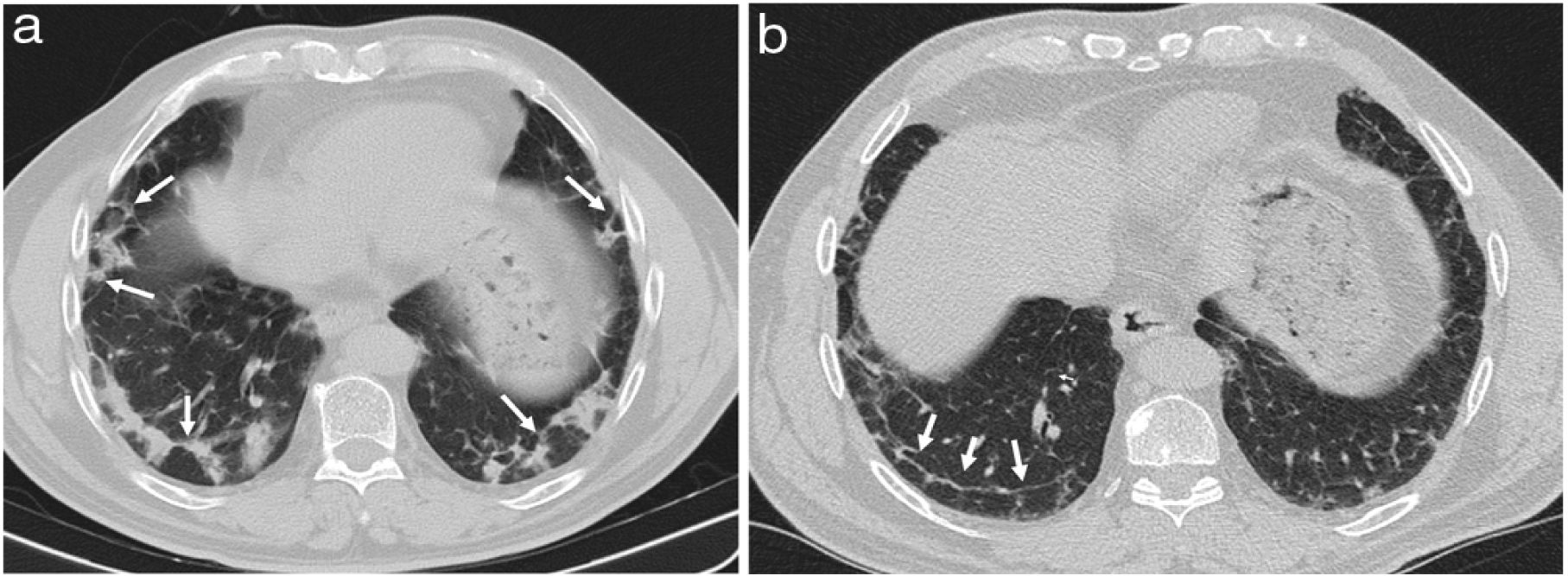

The response may be complete, with the disappearance of the lesions or with minimal residual lesions in the form of subtle ground-glass opacities or subpleural lines (Fig. 7 b). This course is associated with consolidation in the initial studies32 and focal OP.23 However, some series describe a high percentage (greater than 70%) of residual lesions on CT, whose characteristics suggest a pattern of fibrotic NSIP.38,59 This evolution to fibrotic lesions can be seen in rheumatic diseases and, specifically, in antisynthetase syndrome (Fig. 10).7,60

A 60-year-old woman presented with fever, dyspnoea, cough, and chest pain. CT shows consolidation of the right upper lobe (a) and basal ground-glass opacities and a perilobular pattern (arrows) in the left lower lobe. (b). Infection was ruled out, and, given the findings, cryptogenic organising pneumonia was suspected and treated with corticosteroids. In the evolution, the patient showed positive anti-Jo-1 antibodies. The CT performed six months later (c, d) reveals bilateral basal involvement with ground-glass opacities, volume loss and traction bronchiectasis (arrows) concordant with a pattern of non-interstitial non-specific pneumonia.

Rapidly progressive forms of OP are also described, which may be secondary, among others, to collagen diseases.61,62

Considerations on some secondary forms of organising pneumoniaNSIP/OP patternBoth in its idiopathic and secondary forms, primarily associated with autoimmune diseases,7,22,60 OP and NSIP can coexist histologically and in the form of a mixed radiological pattern. In fact, the radiological pattern of OP/NSIP is considered a criterion in the morphological domain for diagnosing interstitial pneumonia with autoimmune features (IPAF).63 This pattern is defined by the presence of basal consolidation, usually juxta-diaphragmatic, associated with signs of fibrosis, with traction bronchiectasis, reticulation, and volume loss.63

OP due to toxicityOP can be the form of presentation of the pulmonary toxicity of numerous drugs, also sometimes overlapping with NSIP.64 Due to its frequency, it is worth noting the association between amiodarone and immunotherapy.64,65

The radiological pattern of OP may overlap with that of drug-induced chronic eosinophilic pneumonia.21,64

OP due to radiotherapyOP secondary to radiotherapy can appear both in the irradiated area and at a distance or in the contralateral lung and with a relatively long interval from the end of treatment, so they may sometimes not be connected. In patients treated for breast cancer, the presence of a spared area of the lung between the band of pneumonitis due to subpleural radiotherapy as a result of direct radiation and consolidation due to OP is characteristic (Fig. 6a), which appears in a series of approximately seven months after treatment.12

It should also be borne in mind that pneumonitis due to radiotherapy can appear late as a pattern of OP with consolidation in the irradiated area in the form of the so-called "radiation recall pneumonitis" in patients receiving chemotherapy and immunotherapy after radiotherapy.66

In six of 16 patients with the "negative relapse sign" described above, there was radiotherapy as part of the medical history, in three of them associated with immunotherapy.58

OP in COVID-19The histological pattern of early-stage SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia was described as diffuse alveolar damage and acute fibrinous and organising pneumonia in most patients.67 However, both from a radiological and pathological point of view, SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia can present as a pattern of OP, especially in advanced stages of the disease in which, apart from the characteristic pattern of multifocal consolidation, the reversed halo sign and perilobular pattern are visible.68–70

ConclusionsThis article describes the different findings that characterise the OP pattern and that the radiologist must consider to alert the clinician about its possible diagnosis, both in the secondary form when it is associated with entities related to it and in its idiopathic form (annex).

Authorship- 1

Responsible for study integrity: JJA-J.

- 2

Study concept: JJA-J, EG-G, AUV, MSM y EFR.

- 3

Study design: not applicable

- 4

Data collection: not applicable.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: not applicable.

- 6

Statistical processing: not applicable.

- 7

Literature search: JJA-J, EG-G, AUV, MSM and EFR.

- 8

Study drafting: JJA-J, EG-G, AUV, MSM and EFR.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: JJA-J, EG-G, AUV, MSM and EFR.

- 10

Approval of the final version:JJA-J, EG-G, AUV, MSM and EFR.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

To Dr Ignacio Aranda, head of the Pathology Service of Hospital General Universitario Dr. Balmis de Alicante [Dr. Balmis de Alicante University General Hospital], for his advice on the pathological aspects of the disease.