Advances in the field of three-dimensional scanning have enabled the development of instruments that can generate images that are useful in medicine. On the other hand, satisfaction studies are becoming increasingly important in the evaluation of quality in healthcare. We aimed to evaluate patients’ and professionals’ satisfaction with the use of a three-dimensional scanner applied to chest wall malformations.

Material and methodsIn the framework of a study to validate the results of three-dimensional scanning technology, we developed questionnaires to measure satisfaction among patients and professionals. We analyzed the results with descriptive statistics.

ResultsWe included 42 patients and 10 professionals. Patients rated the speed and harmlessness positively; the mean overall level of satisfaction was 4.71 on a scale from 1 to 5. Among professionals, the level of satisfaction was lower, especially with regards to the treatment of the image; the mean overall level of satisfaction was 3.1.

ConclusionsPatients rated 3D scanning technology highly, but professionals were less satisfied due to the difficulty of treating the images and lack of familiarity with the system. For this technology to reach its maximum potential, it must be simplified and more widely disseminated.

Gracias a los avances en el campo del escaneado tridimensional (3D) existen instrumentos capaces de generar imágenes con utilidad en medicina. Por otra parte, los estudios de satisfacción ganan cada vez más importancia para evaluar la calidad en la asistencia. Nuestro objetivo es valorar la satisfacción de los pacientes con el uso de un escáner 3D aplicado a las malformaciones de la pared torácica, así como de los profesionales implicados en su uso.

Material y métodosSe han desarrollado encuestas de satisfacción para pacientes y profesionales que han completado pacientes sometidos a escáner 3D en el contexto de un estudio para validar los resultados obtenidos con esta nueva tecnología. Se han obtenido los estadísticos descriptivos de los resultados obtenidos.

ResultadosSe han incluido 42 pacientes y 10 profesionales. Los pacientes evalúan de manera positiva la velocidad y la inocuidad. La media de satisfacción global es de 4,71 en una escala del 1 al 5. Entre los profesionales, la satisfacción es inferior, sobre todo en lo que respecta al tratamiento de la imagen. La media de satisfacción global es de 3,1.

ConclusionesLos pacientes evaluados tienen una buena aceptación y satisfacción con la tecnología de escaneado 3D. No ocurre lo mismo con los profesionales, ya que debido a la dificultad de tratamiento de la imagen y a la falta de familiaridad con el sistema presentan una satisfacción menor. Son necesarios avances en la difusión y simplificación de esta tecnología para aprovechar al máximo su potencial.

Three-dimensional (3D) scanning technology is being developed for use in various scientific fields. Today, the market offers small scanners with sufficient definition to acquire precise images of the body surface.1 Furthermore, programs have been simplified such that they can automatically generate shapes and take measurements, which is why this technology has been hailed as a potentially useful tool in the medical field.2,3

These new systems have brought about increasing numbers of studies on their applications in dentistry, cranial deformities and plastic surgery, as well as chest wall deformities.3,4

Moreover, growing attention has been paid in the last few years to evaluation of patient satisfaction as a marker of healthcare quality. In the context of so-called 'patient-centred care', individual needs and preferences are taken into account in decision-making.5 In patient-centred care, the proper functioning of health systems depends not only on the actions taken by healthcare professionals, but also the patient's subjective experience. Measuring of this perception of and satisfaction with care is as important for quality assessment as evaluating healthcare professionals' conduct.6 It also enables identification of potential areas for improvement in the system. Furthermore, greater patient satisfaction is linked to greater treatment adherence and follow-up of the patient's disease, leading to better outcomes.7 There is therefore a trend towards evaluating the patient experience as part of a comprehensive quality programme.

With the aim of conducting a study to validate the results of a three-dimensional surface scanner versus a traditional radiological test, we asked ourselves what impression patients have of this new technology and whether they will appreciate its benefits over traditional technology. We also asked ourselves whether healthcare professionals involved in patient care find these technologies desirable or reliable and whether they genuinely appreciate their true potential.

The primary objective of this study was to assess patient satisfaction with a three-dimensional scanner for evaluation of chest wall deformities, as well as patient preference for three-dimensional scanning versus traditional radiological testing.

We also aimed to evaluate satisfaction with this new technology among healthcare professionals.

Material and methodsSince 2018, our centre has been developing a study to validate measures and scores obtained from three-dimensional scanning versus magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the chest wall. We conducted satisfaction surveys of patients who underwent both tests in 2018. These patients all had chest wall deformities (pectus excavatum or pectus carinatum). They represented both genders and their ages ranged from seven to 18 years.

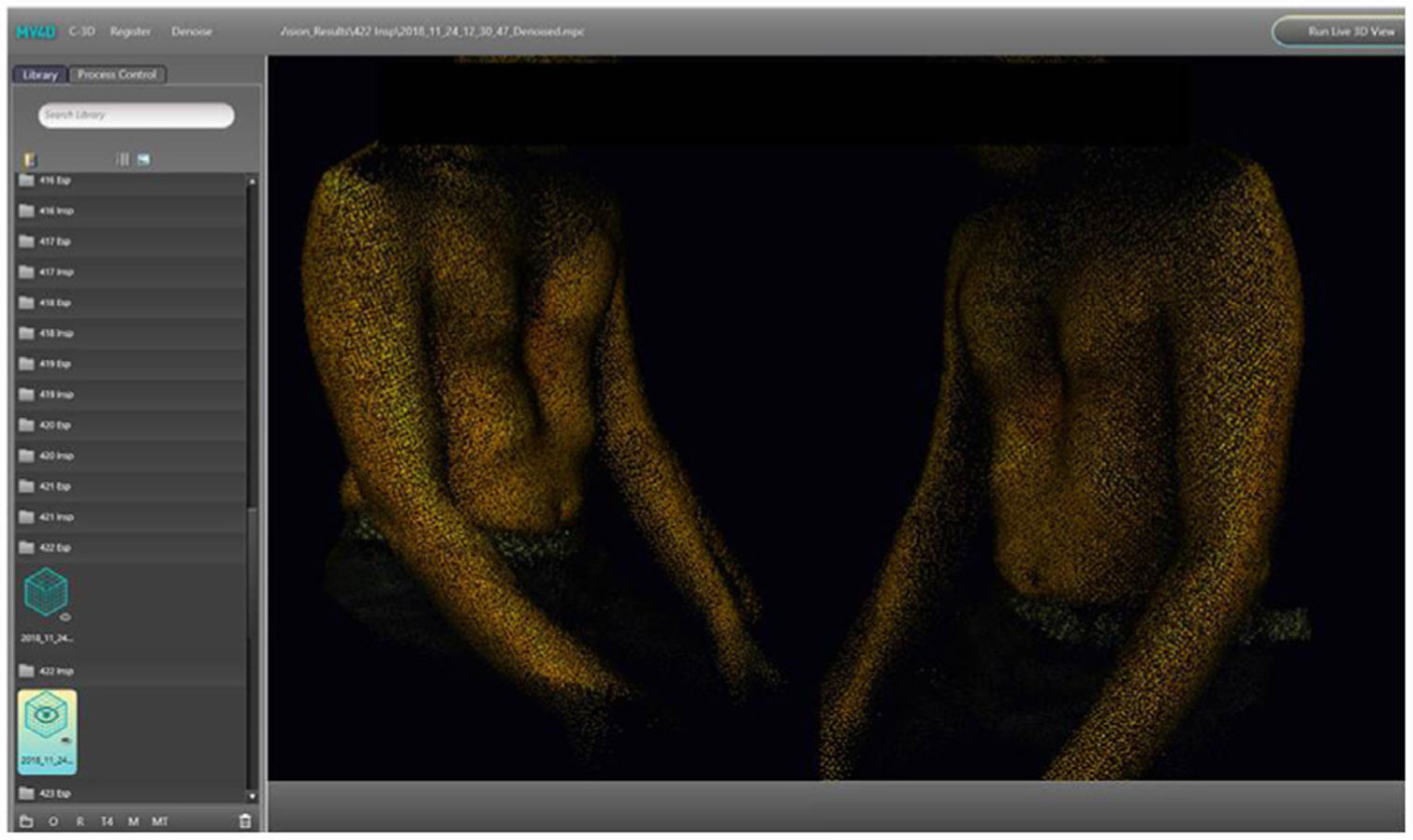

Our three-dimensional scanner is the PocketScan 3D instrument from Mantis Vision™ (Israel) (Fig. 1). It is a small scanner that operates using infrared light. Its precision is 0.2% of the dimension assessed and its time to image acquisition is 600,000 points per second. Images of each patient were acquired on inspiration and expiration (Fig. 2).

The MRI studies were performed using a SIEMENS AVANTO 1.5 T MRI machine which features acquisition of T2-HASTE TRA sequences with 45 slices, a distance factor of 0% and a slice thickness of 4 mm with a time to acquisition of 50 s (4 apnoeas of 12 s) using a 186 × 256 matrix.

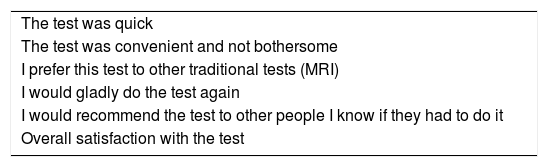

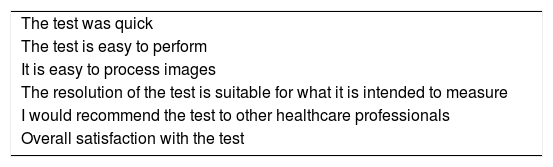

To evaluate satisfaction, in the absence of specific surveys on radiological tests, we developed a survey with the most relevant items to consider in performing the test to assess their acceptance (Table 1). We also prepared a second survey with items on image acquisition and processing to evaluate satisfaction among healthcare professionals (Table 2).

Items assessed on satisfaction survey for family members.

| The test was quick |

| The test was convenient and not bothersome |

| I prefer this test to other traditional tests (MRI) |

| I would gladly do the test again |

| I would recommend the test to other people I know if they had to do it |

| Overall satisfaction with the test |

MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Items assessed on healthcare professionals survey.

| The test was quick |

| The test is easy to perform |

| It is easy to process images |

| The resolution of the test is suitable for what it is intended to measure |

| I would recommend the test to other healthcare professionals |

| Overall satisfaction with the test |

Data were collected anonymously in an Excel table (Microsoft® Excel® 2011 for Mac Version 14.7.0). Descriptive statistics and percentages for each score, as well as means and standard deviations were calculated for each item individually in both groups.

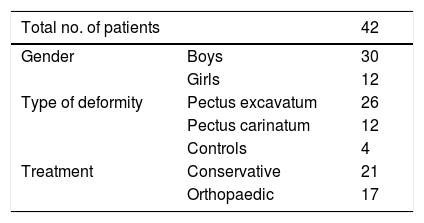

ResultsDuring this period, 42 patients met the inclusion criteria and completed the survey. These patients ranged in age from seven to 18 years old and had a mean age of 13.6. Concerning chest wall deformities, 26 patients had pectus excavatum and 12 patients had pectus carinatum. Four patients undergoing orthopaedic treatment had complete correction of the deformity when the test was performed, and they were taken as controls. Patient characteristics are summarised in Table 3.

Ten healthcare professionals involved in at least one of the phases of the study filled in the satisfaction survey for healthcare professionals. They consisted of eight physicians and two other healthcare professionals.

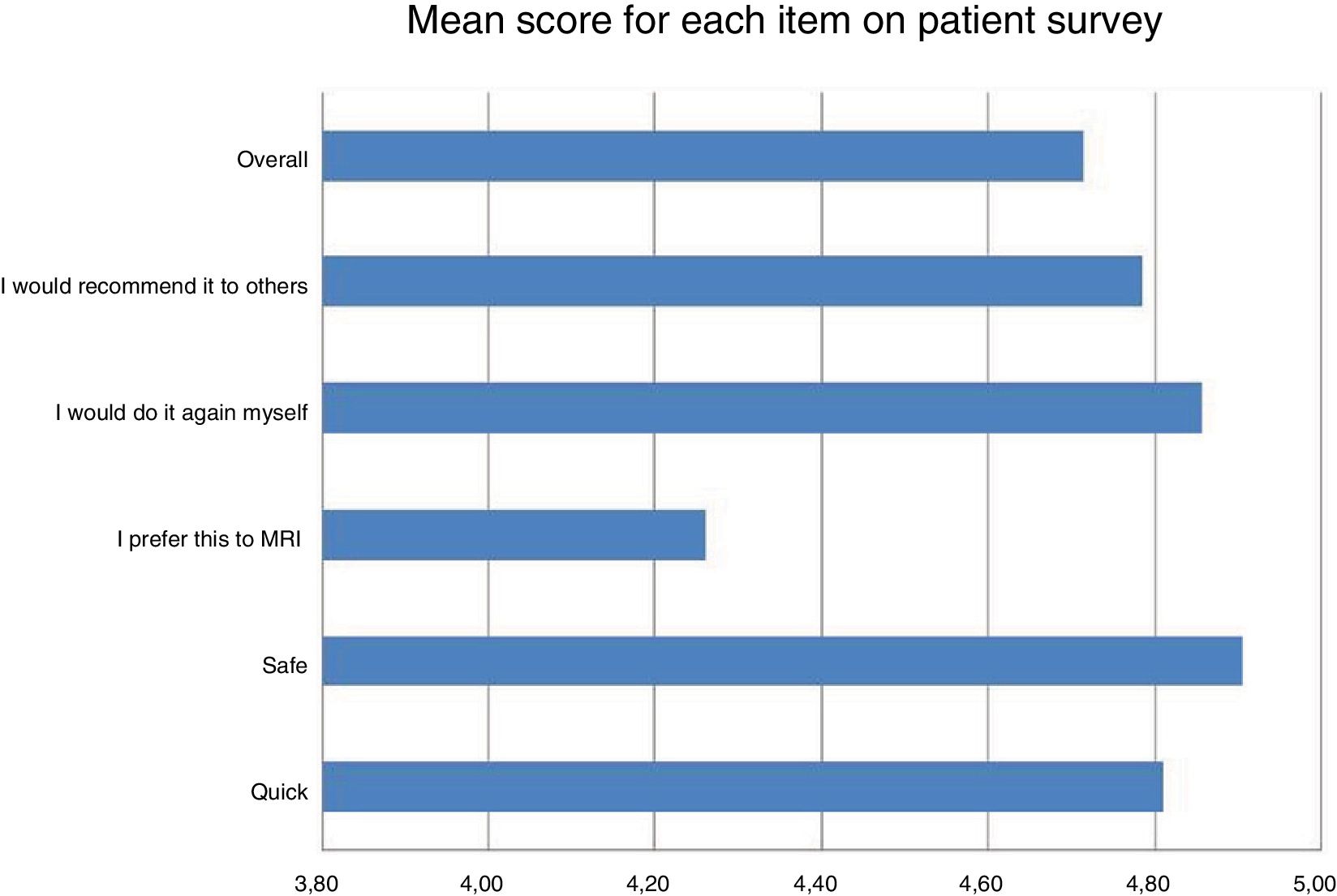

Patient surveysScores for each item ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (completely agree).

The mean for all items evaluated exceeded 4 points (Fig. 3). The most positively assessed aspects included test safety, with a mean of 4.9 (standard deviation [SD] 0.54), and speed, with a mean of 4.8 (SD 0.29).

Proportionally, most responses were 4–5 (92%). Responses regarding preference between three-dimensional scanning and MRI were more mixed: two patients answered that they would prefer MRI, and nine (21.4% of the total) expressed no preference between one test and the other.

Of all the patients, 95.2% would certainly or almost certainly recommend the test to other people, and mean overall satisfaction was 4.71 (SD = 0.54).

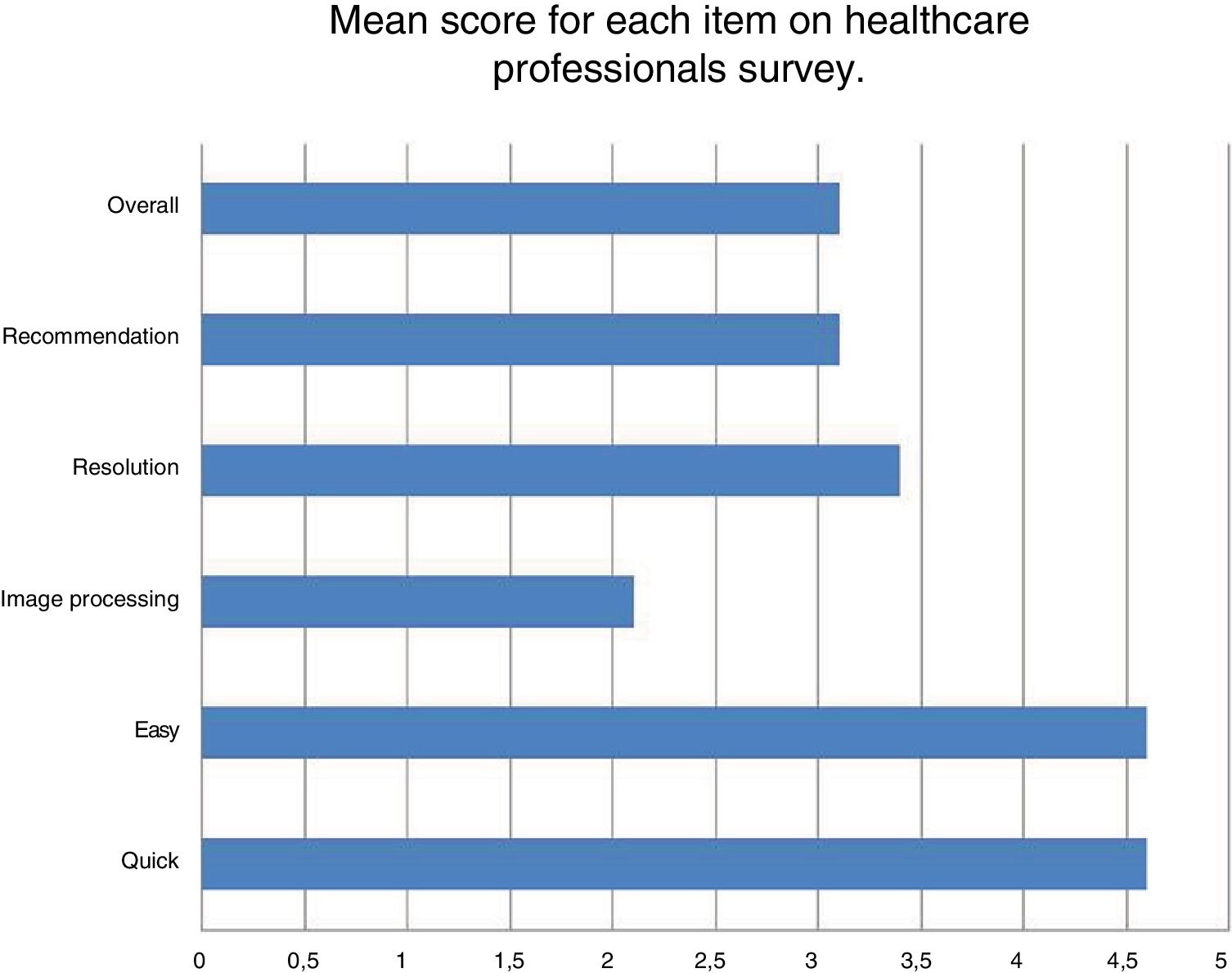

Healthcare professional surveysFor healthcare professionals, the means for the different items evaluated exhibited greater disparities (Fig. 4). Speed and ease of use both had a mean score of 4.6 (SD = 0.66). These were the most positively assessed aspects.

Ease of image processing had a mean score of 2.1 (SD = 1.13), and resolution had a mean score of 3.4 (SD = 1.2). Just 30% of the healthcare professionals would certainly or almost certainly recommend the test to a colleague. Overall satisfaction had a mean score of 3.1 (SD = 1.51).

DiscussionSurface scanning has significant potential in the medical field, especially in diseases and specialisations that require a study of anatomy and prominences, and in patients of a young age8 as sedation can be foregone and ionising radiation is not needed.

The concept of satisfaction is well-defined in the scientific literature. It is a psychological state that occurs following the use of a service compared to the baseline state of expectation of the use of that service.9,10 Satisfaction is subjective, and therefore tied to a number of factors that must be taken into consideration, especially when an individual is a patient and the service in question is health-related, as in our study.11,12

In recent times, surveys have gained popularity as a means of evaluating healthcare quality with respect to patient satisfaction with the services provided.13

At present, there is no specific questionnaire for assessing satisfaction in relation to imaging tests. Therefore, in this study, we opted to adapt a series of basic, generic questions so that they could be answered by patients in the age range studied, to reflect those patients' acceptance of and satisfaction with the test performed and to compare it to a classic radiological test.

The results revealed that the items that assessed the convenience and speed of the test achieved the highest mean score. In our study, the duration of image acquisition did not exceed four seconds, whereas MRI sequences require at least 10 min of machine use.

When we compared this test to the traditional test (in this case, the MRI that had been performed the same day), we found that 23% of patients showed no preference for one test or the other, as this item had a lower mean score than all the others. This result might have been due to patient trust in traditional tests and a certain reluctance to accept more novel tests that are still being proven. Factors such as the apparent complexity of MRI and test duration may have caused users to associate MRI with a higher-quality evaluation. Indeed, MRI provides more information. However, it is our duty as healthcare professionals to explain to patients that this additional information can be excessive and does not always translate to better care, since each diagnostic test is intended to meet a particular clinical need.

Nevertheless, performing the test does not pose a problem for the patient, and it does enjoy good acceptance, as most patients responded with the most positive score when asked if they would repeat the study or if they would recommend it to other people. Mean overall satisfaction with the test was 4.72, which is considered very positive.

Regarding satisfaction among healthcare professionals with the test, we found more negative scores for certain items essentially tied to the work that the healthcare professionals had to do after images were acquired.

It is very important, but not always easy, to adapt new technologies to the healthcare setting. In our setting, the 3D scanner offers certain advantages that cause us to believe that this effort is worthwhile.

If the technology is not intuitive or accessible, then healthcare staff must make an extra effort to train themselves in its use, and this is counterproductive.

Scores for speed and simplicity were high, though slightly lower than those given by patients.

Much lower scores were given for ease of image processing, with 60% of healthcare professionals scoring it a 1 or a 2 (disagree or strongly disagree). This was due to the difficulties in measurements encountered at the start of the study. The software program for image processing was unintuitive and difficult to use, compelling us to look for alternative programs. This unfortunate occurrence delayed the process of taking measurements and explains why satisfaction was low in this regard.

Scores for both repetition and recommendation were low, and we attribute this to the same reason. Once initial difficulties had been overcome, the procedure was simplified, though this first impression of the three-dimensional scanning technology did have a negative impact on the healthcare professionals. Even so, mean overall satisfaction with the test was 3.1.

In conclusion, it can be said that the 3D scanner enjoyed good acceptance among patients.

We perceived that the healthcare professionals recognised the advantages of this technology but were highly dissatisfied with image processing.

We postulate that the development of applications and simpler software would facilitate use of the three-dimensional scanner by untrained staff and improve satisfaction.

These technologies offer a number of advantages that cannot be overlooked. They must be simplified to encourage healthcare professionals to make an effort to learn and use them as well as to promote the validation of their results and their dissemination and presentation to patients.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for the integrity of the study: SF, MB, FD, JMP, TL and EA.

- 2.

Study conception: SF, EA and TL

- 3.

Study design: SF, MB, DF and JMP.

- 4.

Data collection: FD, MB, SF, JMP and TL.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: SF, MB and FD.

- 6.

Statistical processing: SF and JMP.

- 7.

Literature search: SF and JMP.

- 8.

Drafting of the paper: SF and EA.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: TL and EA.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: SF, MB, FD, JMP, TL and EA.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

FundingThis study was conducted as part of a study funded by a 2017 research grant from the Junta de Castilla y León [Castile and León Council]. Reference: GRS 1571/A/17.

We would like to thank Luis García Pérez from 3D Digitisation and Dr Santiago Vivas for his advice and support.

Please cite this article as: Fuentes S, Berlioz M, Damián F, Pradillos JM, Lorenzo T, Ardela E. Satisfacción de pacientes y profesionales con las nuevas tecnologías de imagen tridimensional aplicadas a la medicina. Radiología. 2020;62:46–50.