Self-limiting sternal tumors of childhood (SELSTOC) are rapidly growing sternal lesions that tend to resolve spontaneously. Patients have no history of infection, trauma, or neoplasms, and the most likely etiologyis an aseptic inflammatory reaction of unknown origin. The differential diagnosis includes a wide spectrum of lesions such as tumors, infections, malformations, or anatomic variants.

Material and methodsWe analyzed all cases of sternal masses in pediatric patients seen between 2012 and 2019; five of these had findings compatible with SELSTOC. We retrospectively recorded patients’ race, sex, age, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, imaging tests, treatment, and follow-up.

ResultsWe present five cases of rapidly growing sternal lesions whose clinical and radiological features are compatible with SELSTOC. In the absence of alarming symptoms and laboratory markers, watchful waiting could be an appropriate therapeutic approach. However, patients with some findings such as fever, elevated acute phase reactants, and/or comorbidities could require therapeutic interventions such as antibiotics or percutaneous drainage. In our series, depending on the clinical presentation and the patient’s comorbidities, different therapeutic approaches were adopted (a conservative approach in two patients, antibiotics in three patients, and percutaneous drainage in one patient). In all cases, the sternal lesion was absent at discharge and/or at later follow-up visits.

ConclusionRadiologists and pediatricians must be aware of this entity and the different diagnostic and therapeutic approaches to rapidly growing sternal lesions in pediatricpatients because recognizing SELSTOC can avoid unnecessary diagnostic tests and/or disproportionate therapeutic strategies.

Self-limiting sternal tumours of childhood (SELSTOC) son lesiones esternales autolimitadas, de crecimiento rápido, con tendencia a la resolución espontánea. No existen antecedentes infecciosos, traumáticos o neoplásicos y su etiología más probable es que se trate de una reacción inflamatoria aséptica de origen actualmente desconocido. El diagnóstico diferencial incluye un amplio espectro de lesiones como tumores, infecciones, malformaciones o variantes anatómicas.

Material y métodosSe analizan los casos de masas esternales en población pediátrica entre 2012 y 2019; de ellos, cinco presentan hallazgos compatibles con masas esternales que concuerdan con SELSTOC. Se obtienen datos acerca de la raza, sexo del paciente, edad, presentación clínica, hallazgos de laboratorio, pruebas de imagen, tratamiento y seguimiento de manera retrospectiva.

ResultadosPresentamos 5 casos de lesiones esternales de crecimiento rápido cuyas características clínicas y radiológicas son compatibles con SELSTOC. Un enfoque terapéutico de “esperar y ver” puede ser adecuado en ausencia de síntomas de alarma y de marcadores de laboratorio. Sin embargo, algunas características como fiebre, elevación de reactantes de fase aguda y comorbilidades del paciente pueden requerir actitudes terapéuticas como antibióticos o drenajes percutáneos. En nuestro caso, dependiendo de la presentación clínica y de las comorbilidades del paciente, se adaptaron diferentes medidas terapéuticas (medidas conservadoras en 2 pacientes, antibióticos en 3 pacientes o drenaje percutáneo en 1 paciente). En todos ellos la lesión esternal estaba ausente al alta o en controles posteriores.

ConclusiónRadiólogos y pediatras deben ser conscientes de esta entidad y de sus diferentes enfoques diagnósticos y terapéuticos, ya que su reconocimiento puede evitar medidas diagnósticas inútiles o estrategias terapéuticas desproporcionadas.

Chest wall tumours, whether benign or malignant, are rare in the paediatric population. In 2010, Winkel et al.1 reported a new entity known as self-limiting sternal tumours of childhood (SELSTOC). These are self-limiting, rapidly-growing tumours with a tendency to resolve spontaneously. On ultrasound they are typically dumbbell-shaped. They are not associated with a history of infection, trauma or neoplasm. Their aetiology is most likely an aseptic inflammatory reaction of a currently unknown origin.

Material and methodsCases of sternal masses in the paediatric population between 2012 and 2019 were analysed; five of these cases presented findings consistent with sternal masses that fulfilled SELSTOC criteria. Data on patient race, sex, age, clinical presentation, laboratory findings, imaging tests, treatment and follow-up were collected retrospectively.

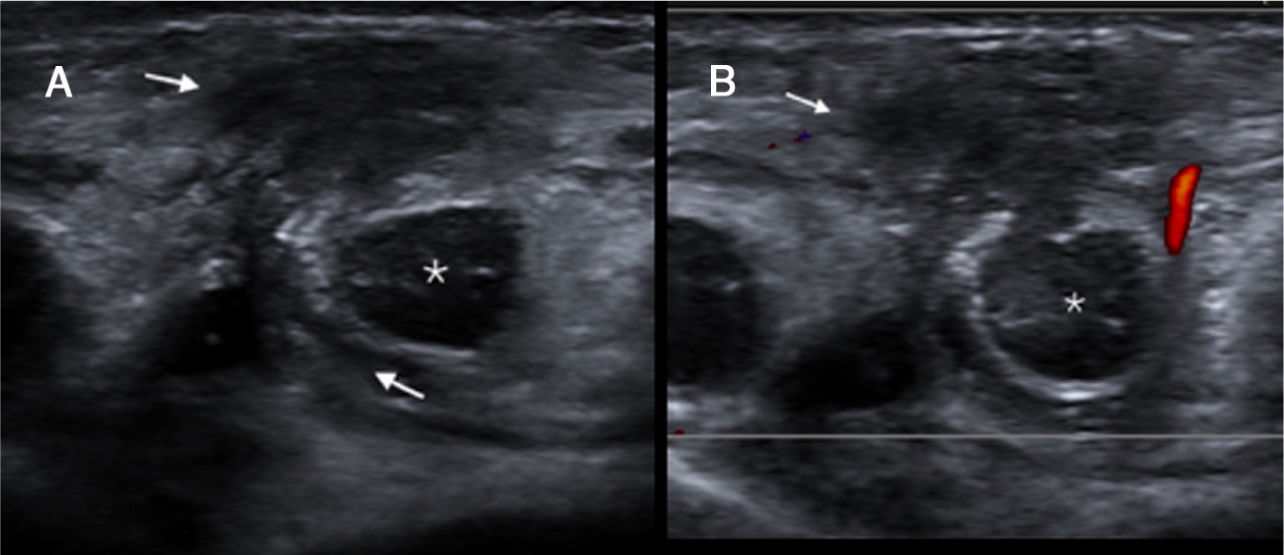

ResultsFour cases corresponded to infants 3–18 months of age seen in the emergency department due to recent onset of a presternal mass with no fever, trauma or other history of note. One patient was found to have mild underlying skin erythema; another was found to have a painful mass. All were found on ultrasound to have an avascular, presternal or dumbbell-shaped hypoechoic mass between the sternum and the ribs (Fig. 1). In the absence of symptoms or laboratory abnormalities, 3 patients were discharged with no antibiotic therapy and one was discharged following a brief cycle of antibiotics (amoxicillin and clavulanic acid). Complete resolution of the "mass" was demonstrated 1–6 months after onset (Fig. 2).

(A) Longitudinal projection of ultrasound in sternal region. A hypoechoic lesion with spread anterior and posterior to the sternum (white arrow) is seen. There is an inflammatory process that presses against the line of pleural reflection (red arrow); (* = rib). (B) Ultrasound in patient follow-up showing complete resolution of this lesion after conservative measures (* = rib; T: thymus).

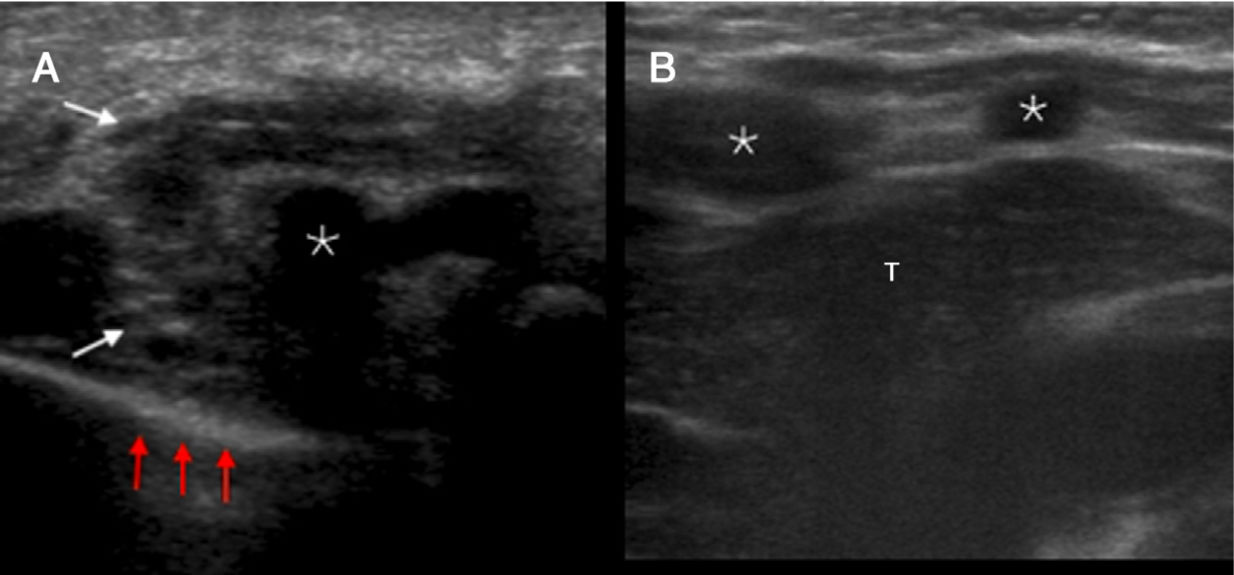

The fifth case in our series was an infant with trisomy 21 and the son of a mother with HIV with suitable prenatal monitoring. During an admission to the intensive care unit due to respiratory distress and laryngomalacia, he showed symptoms of irritability and a fever of up to 39°C. Infection markers (C-reactive protein [CRP] and leukocytosis) were found to be elevated. Blood samples taken for blood cultures tested positive for methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA). Two peripheral venous lines were considered to be the most likely origin of the infection and were removed. Three days later, clinical examination revealed a fluctuating presternal lesion, whereupon a soft-tissue ultrasound was ordered. This showed a dumbbell-shaped lesion 1 cm in length, located in the subcutaneous cellular tissue spreading towards the retrosternal fat through the costosternal synchondrosis. In this case, given the suspected superinfection, percutaneous drainage (Fig. 3) was performed with a 5 F pigtail catheter, which was removed the next day. A small amount of purulent matter (approximately 3 cm3) was aspirated and proved to be positive for MSSA. This patient was given a broad-spectrum empirical antibiotic (teicoplanin) which was de-escalated to cloxacillin + gentamicin for 15 days on receipt of the positive blood culture result. Once this treatment ended, the patient was placed on a regimen of oral cefadroxil for a further 4 weeks. The patient was discharged following resolution of his baseline disease and sternal lesion, making a full recovery.

(A) Coronal projection of ultrasound in sternal region. Dumbbell-shaped hypoechogenic lesion in the subcutaneous cellular tissue with spread to the retrosternal fat through the costosternal synchondrosis (white arrow). (B) Ultrasound-guided percutaneous drainage with a 5 F pigtail catheter. L: lung; S: sternum.

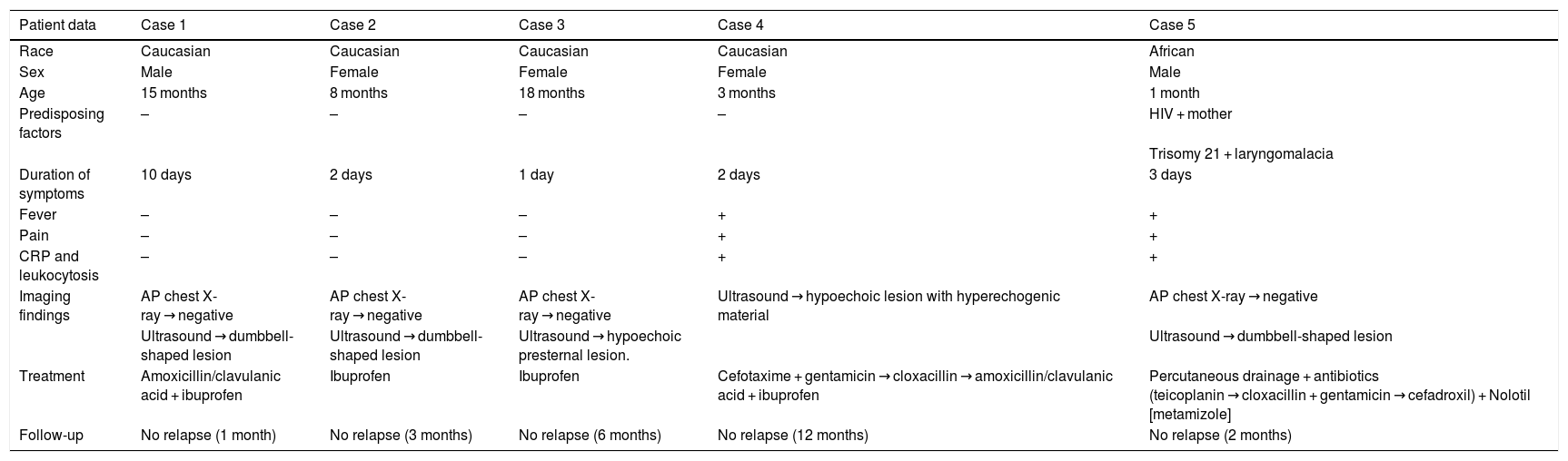

Our 5 patients' demographic, clinical, ultrasound and treatment data are summarised in Table 1.

Patients' demographic, clinical, ultrasound and treatment data.

| Patient data | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | Caucasian | Caucasian | Caucasian | Caucasian | African |

| Sex | Male | Female | Female | Female | Male |

| Age | 15 months | 8 months | 18 months | 3 months | 1 month |

| Predisposing factors | – | – | – | – | HIV + mother |

| Trisomy 21 + laryngomalacia | |||||

| Duration of symptoms | 10 days | 2 days | 1 day | 2 days | 3 days |

| Fever | – | – | – | + | + |

| Pain | – | – | – | + | + |

| CRP and leukocytosis | – | – | – | + | + |

| Imaging findings | AP chest X-ray → negative | AP chest X-ray → negative | AP chest X-ray → negative | Ultrasound → hypoechoic lesion with hyperechogenic material | AP chest X-ray → negative |

| Ultrasound → dumbbell-shaped lesion | Ultrasound → dumbbell-shaped lesion | Ultrasound → hypoechoic presternal lesion. | Ultrasound → dumbbell-shaped lesion | ||

| Treatment | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid + ibuprofen | Ibuprofen | Ibuprofen | Cefotaxime + gentamicin → cloxacillin → amoxicillin/clavulanic acid + ibuprofen | Percutaneous drainage + antibiotics (teicoplanin → cloxacillin + gentamicin → cefadroxil) + Nolotil [metamizole] |

| Follow-up | No relapse (1 month) | No relapse (3 months) | No relapse (6 months) | No relapse (12 months) | No relapse (2 months) |

AP: anteroposterior.

Our study presents 5 cases of rapidly-growing sternal masses, the findings for which are summarised in Table 1. Four patients were Caucasian and one was African. Mean patient age was 9 months (range 1–18 months). At the time of consultation, the duration of symptoms was less than 2 weeks. Only two cases presented signs of local inflammation with no history of trauma or prior neoplasm. In all cases, there was spontaneous resolution of symptoms following symptomatic treatment (2 cases), antibiotic treatment (2 cases) or antibiotic treatment and percutaneous drainage with a 5 F pigtail catheter (1 case). One of them had a bacterial superinfection of the lesion, probably due to contamination during bacteraemia while the patient was admitted to the intensive care unit.

An anteroposterior chest X-ray was performed in all patients, although it did not provide any data of note. Ultrasound was the diagnostic test performed in all cases, showing the typical dumbbell-shaped lesion but not any lesion in the bone or underlying cartilage in the sternum, ribs or sternocostal joints. In all cases, a high-frequency (12 MHz) linear transducer was used.

The time needed for complete disappearance of symptoms in our cases ranged from 1 month to 12 months. We suggest that the first ultrasound check-up be 2 weeks to 1 month after the initial presentation, provided there is no clinical worsening. Only after the disappearance of the lesion is confirmed may check-ups be spaced out or even stopped.

Although SELSTOC are self-limiting sternal lesions characterised by aseptic inflammation (cold abscesses), treatment strategy in our last case was justified in view of the patient's clinical condition and the absence of clinical guidelines in this regard. Given the underlying disease, positive blood cultures, typical ultrasound findings and the possibility of superinfection, drainage of this sternal lesion was reasonable.

Depending on the patient's clinical presentation and comorbidities, different therapeutic measures (conservative measures, antibiotics or percutaneous drainage) were pursued. In all the patients, the sternal lesion was absent at discharge or in subsequent check-ups.

According to the scientific literature published in this regard, our findings were similar to those of Roukema et al.,2 Howard et al.,3 Nikolarakou et al.,4 Adri and Kreindel,5 Ilivitzki et al.6 and Winkel et al.1 Winkel et al.1 were the first to report 14 cases of rapidly-growing sternal masses, which they named SELSTOC. They attributed these findings to self-limiting aseptic inflammation and therefore proposed a wait-and-see approach as the most suitable approach to treatment.

Roukema et al.2 reported 3 cases of patients 11–14 months of age with painful sternal lesions and no fever. Two patients required surgical drainage and the last one underwent percutaneous drainage.

Howard et al.3 also reported 4 cases of patients 9–16 months of age. Only one patient had fever in the first examination. One patient underwent biopsy, two aspiration and a fourth was treated with symptomatic measures. All patients recovered with no subsequent relapses.

Nikolarakou et al.4 also reported 3 cases, all treated differently with the same outcome. One patient was treated with oral antibiotics, another was treated with surgical drainage and the last was treated with antibiotics plus percutaneous drainage. All the patients remained asymptomatic during follow-up with no relapses hitherto.

Adri and Kreindel5 reported the cases of two patients, one 12 months old and the other 22 months old, treated with conservative measures without complications.

Lastly, Ilivitzi et al.6 reported three different cases with findings consistent with SELSTOC. One of them underwent percutaneous drainage (with negative cytology and culture). All of them underwent a follow-up ultrasound with complete disappearance of the sternal lesion within a few months.

According to Winkel et al.1, SELSTOC are self-limiting, rapidly-growing sternal lesions in which conservative treatment may be indicated in most cases. However, some patient characteristics such as fever, elevated infection markers, ultrasound findings and comorbidities may require more invasive approaches such as antibiotic treatment (with coverage for MSSA7) or percutaneous drainage.

Paediatric malignant tumours are rare and unlikely in the case of a rapidly-growing lesion. SELSTOC should be suspected in a context of a rapidly growing presternal mass with no effect on the patient's general condition and no other abnormalities on physical examination in infants younger than 20–24 months. A soft-tissue ultrasound should be performed to examine the characteristics and extent of the lesion and to demonstrate the typical dumbbell shape on ultrasound. We suggest avoiding a chest X-ray given its limited diagnostic yield. Ultrasound is the test of choice.

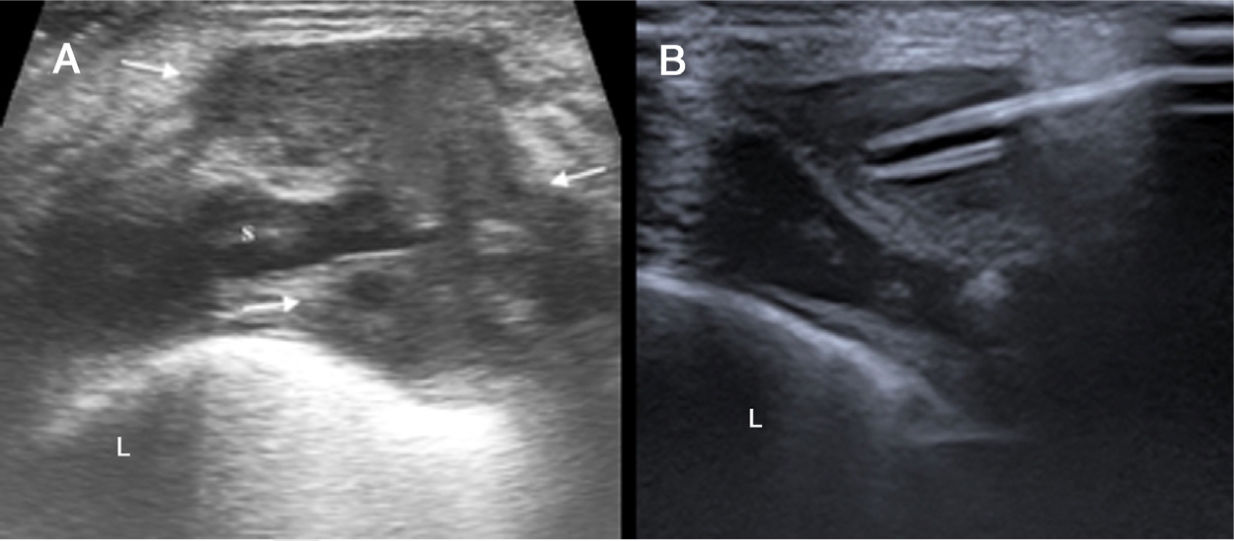

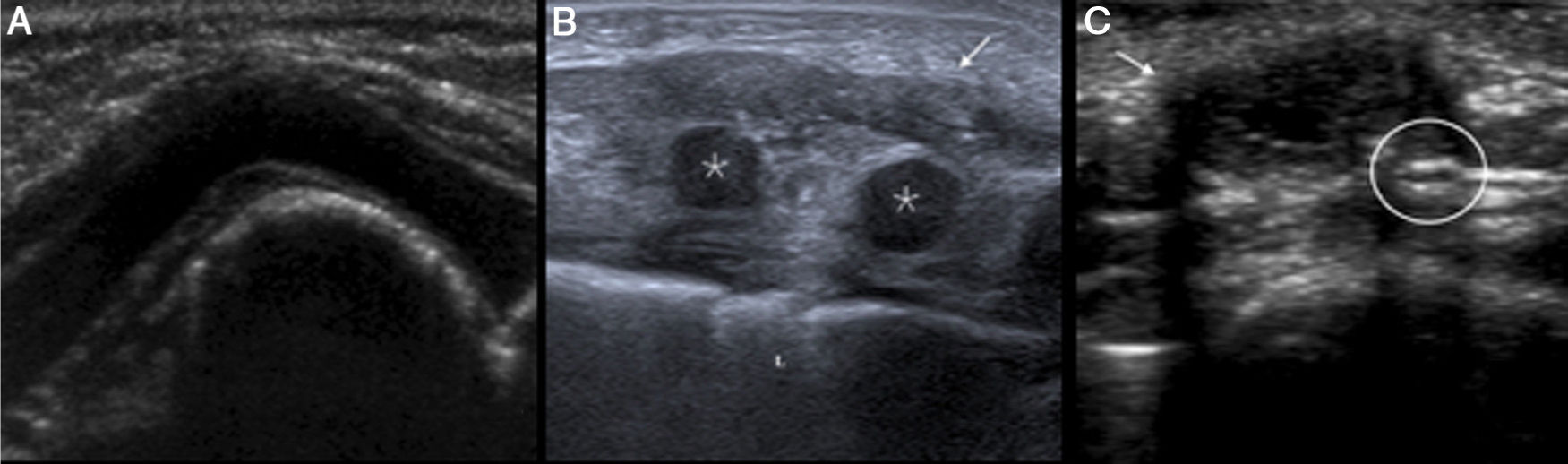

A dumbbell-shaped lesion in the subcutaneous cellular tissue with spread through the sternal synchondrosis may be suggestive of a SELSTOC, although the differential diagnosis may include the following (Figs. 4 and 5):

- •

Cartilage prominence, as an anatomical variant of the ribcage.

- •

An abscess or foreign-body granuloma, which are unlikely in the absence of prior trauma or surgery.

- •

Recurring chronic multifocal osteomyelitis primarily affects bone and presents as chronic aseptic inflammation. Although it has been reported in patients under 1 year of age, it is much more common in pre-teen patients and older children. The clinical picture is insidious, with a progressive mass effect, and inflammatory signs are usually not very prominent at the start of the disease. It may be accompanied by joint pain and a firm palpable mass (corresponding to the bone and its periosteal reaction), and the mass persists although inflammation remits with treatment.

- •

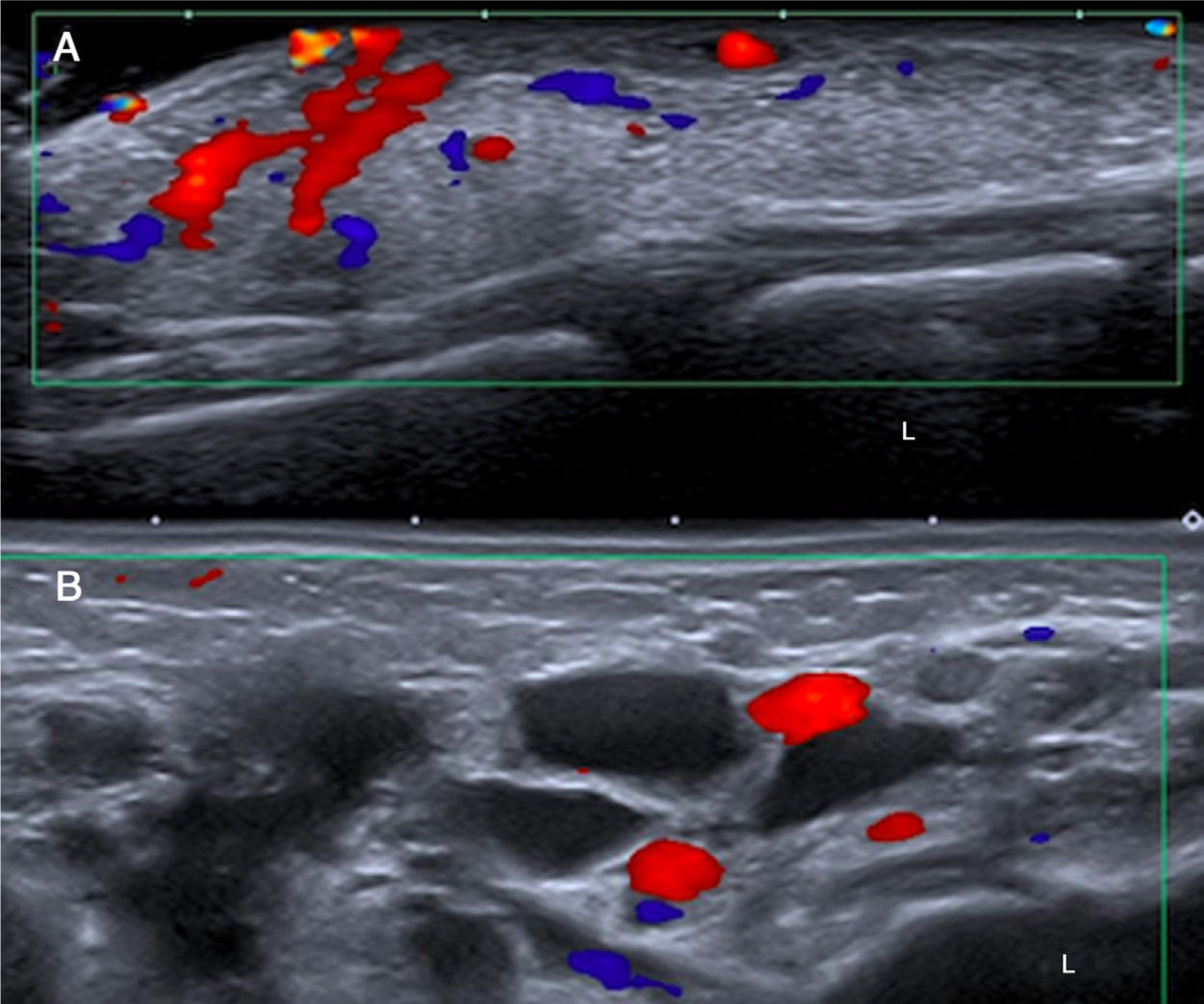

Haemangioma as a hyperechogenic solid vascular lesion in the subcutaneous cellular tissue, with high vascular density, arteries with low resistance and veins with a monophasic predominance.

- •

Lymphatic malformations, formerly known as lymphangiomas, as benign multicystic lesions which may bleed and become enlarged. They are rarely located in the sternum unless the patient has an extensive cervicothoracic malformation.

(A) Costal cartilage prominence consisting of an angulation leading to a deformity in the ribcage. (B) Hypoechogenic spread of subcutaneous fat in sternal region consistent with abscess following a median sternotomy (white arrow) (* = rib). (C) Painless hypoechogenic lesion (white arrow) with a hyperechogenic focus (white circle). The patient has a history of sternotomy 3 years earlier; hence, foreign-body granuloma was suggested.

(A) Extensive hyperechogenic lesion in the subcutaneous cellular tissue of the anterior region of the chest, consistent with haemangioma. Doppler ultrasound shows the vascular nature of the lesion. (B) Lymphatic malformations are benign multicystic lesions which may bleed and become enlarged. They are rare in a sternal location in isolation. Image B shows an axial projection in the right supraclavicular region, revealing a multicystic lesion with no Doppler flow consistent with a lymphatic malformation. L: lung.

In summary, SELSTOC are rapidly-growing benign sternal masses whose aetiology remains unknown. A SELSTOC diagnosis is suspected in view of its typical clinical presentation in the absence of a history of infection, trauma or neoplasm. A dumbbell-shaped lesion is a typical finding on ultrasound. Clinicians and radiologists should be capable of identifying this lesion to avoid unnecessary diagnostic and treatment methods, since conservative treatment may be appropriate in most cases. However, more aggressive treatments such as antibiotic therapy and percutaneous drainage may be considered in the case of a painful lesion, fever, increased infection markers or positive blood cultures.

AuthorshipResponsible for study integrity: JAS.

Study concept: JAS.

Study design: JAS.

Data acquisition: JGP, MCCC, CCP.

Data analysis and interpretation: JAS, JGP, MCCC, CCP.

Statistical processing: N/A.

Literature search: N/A.

Drafting of the article: CGH, MRP, DCR.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: CGH, MRP, DCR.

Approval of the final version: JAS, CGH, JGP, MCCC, CCP, MRP, DCR.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Alonso Sánchez J, Gallego Herrero C, García Prieto J, Cruz-Conde MC, Casado Pérez C, Rasero Ponferrada M, et al. Tumores esternales autolimitados en la edad pediátrica (SELSTOC): un reto diagnóstico. Radiología. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rx.2020.04.007