Assessing the hilum of the lung is a common challenge in daily practice because various structures converge in this complex anatomic region. Because chest X-rays are widely available and deliver relatively low doses of radiation, they continue to be the most common imaging test, although new imaging modalities have decreased the use of chest X-rays for differentiating between true abnormalities and superimposed lung opacities. This article reviews the literature and describes the principal anatomic relations of the lung hilum through illustrative cases to enable the two most important radiologic signs to be identified: “hilum overlay” and “hilum convergence”. In the initial imaging evaluation of patients with cardiothoracic disease, knowledge of these basic principles facilitates the three-dimensional location of lesions in a single-plane image, optimizing time and resources.

El análisis del hilio pulmonar es un reto frecuente en la práctica diaria, por tratarse de una región anatómica compleja donde confluyen varias estructuras. La radiografía de tórax, por su alta accesibilidad y baja dosis de radiación, se mantiene como la primera técnica de imagen solicitada, pese a que las nuevas modalidades han disminuido su uso en el momento de diferenciar verdaderas anormalidades de opacidades pulmonares superpuestas. Se realizó una revisión bibliográfica que ilustra mediante casos didácticos sus principales relaciones anatómicas, lo que permite identificar los signos radiológicos que revisten mayor importancia: “sobreposición hiliar” y “convergencia hiliar”. En la valoración inicial del paciente con patología cardiotorácica, tener conocimiento de estos principios básicos facilita localizar tridimensionalmente lesiones en una imagen planar, optimizando tiempo y recursos.

A common, everyday problem of conventional radiology is the analysis of the pulmonary hilum, a complex anatomical structure in which arteries, veins, bronchi, pleura, pericardium and nerves converge, making it difficult to characterise a lesion's dependence. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are commonly used for this part of the chest, but anteroposterior X-ray is usually the first and only method available to the physician making the initial assessment.

Due to wide variation in the normal appearance of the hilum, it is often wrongly reported as abnormal when it is not, and vice versa. Even though X-rays were one of the earliest imaging methods to be developed, they still play a leading role and carry great importance in clinical practice. The chest X-ray is the preferred imaging study when thoracic disease is suspected. Moreover, its accessibility and low radiation dose give it an advantage over other imaging techniques. This literature review discusses two classic radiological signs which are extremely useful in a three-dimensional characterisation of a two-dimensional study. We then move on with an anatomical-radiological focus on the "hilum overlay sign" and the "hilum convergence sign" described by Felson in 1973.1 These remain the two most important tools in differentiating abnormalities of the hilum, even today, when artificial intelligence is aiming to taking over chest X-ray analysis.

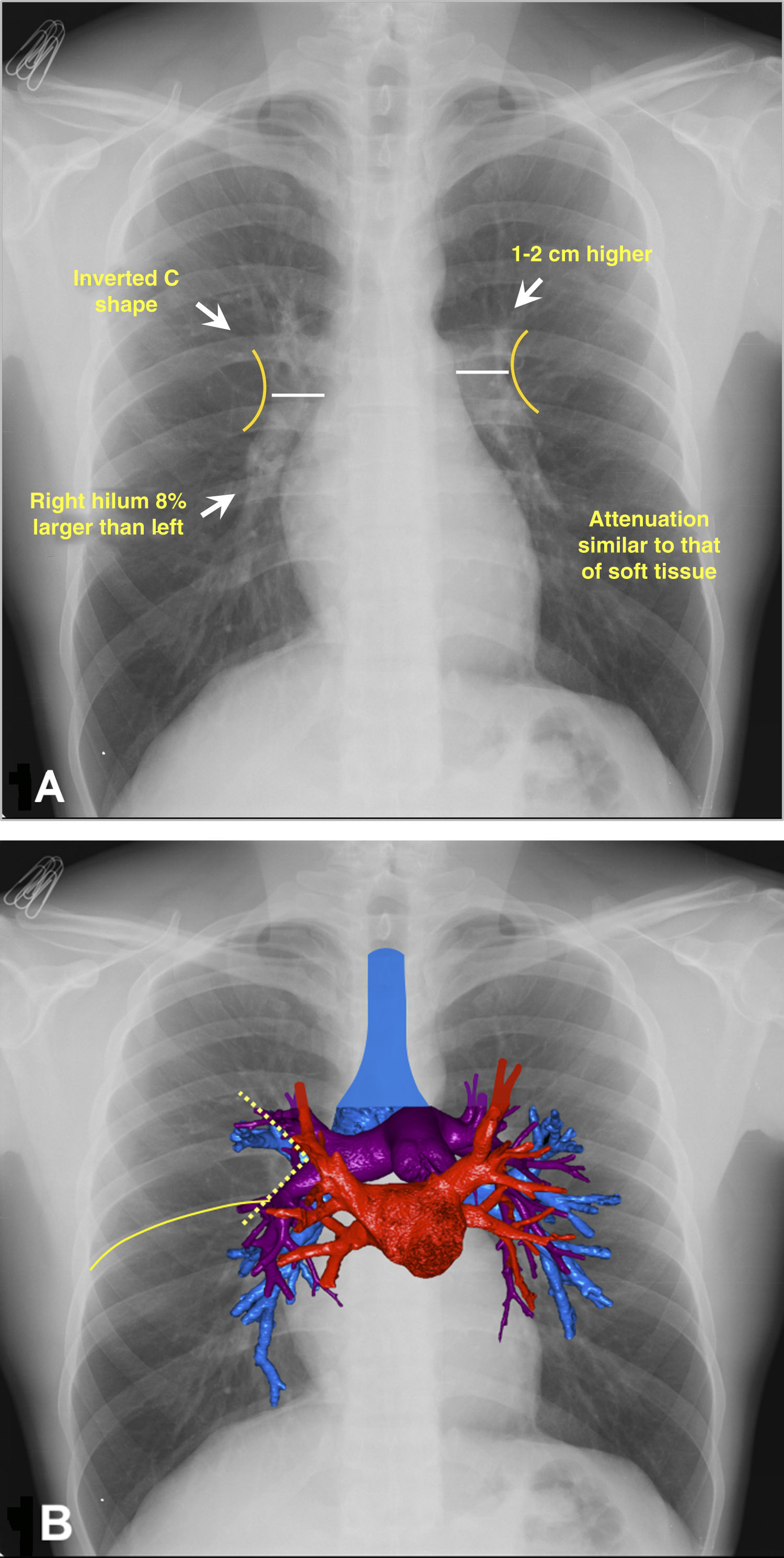

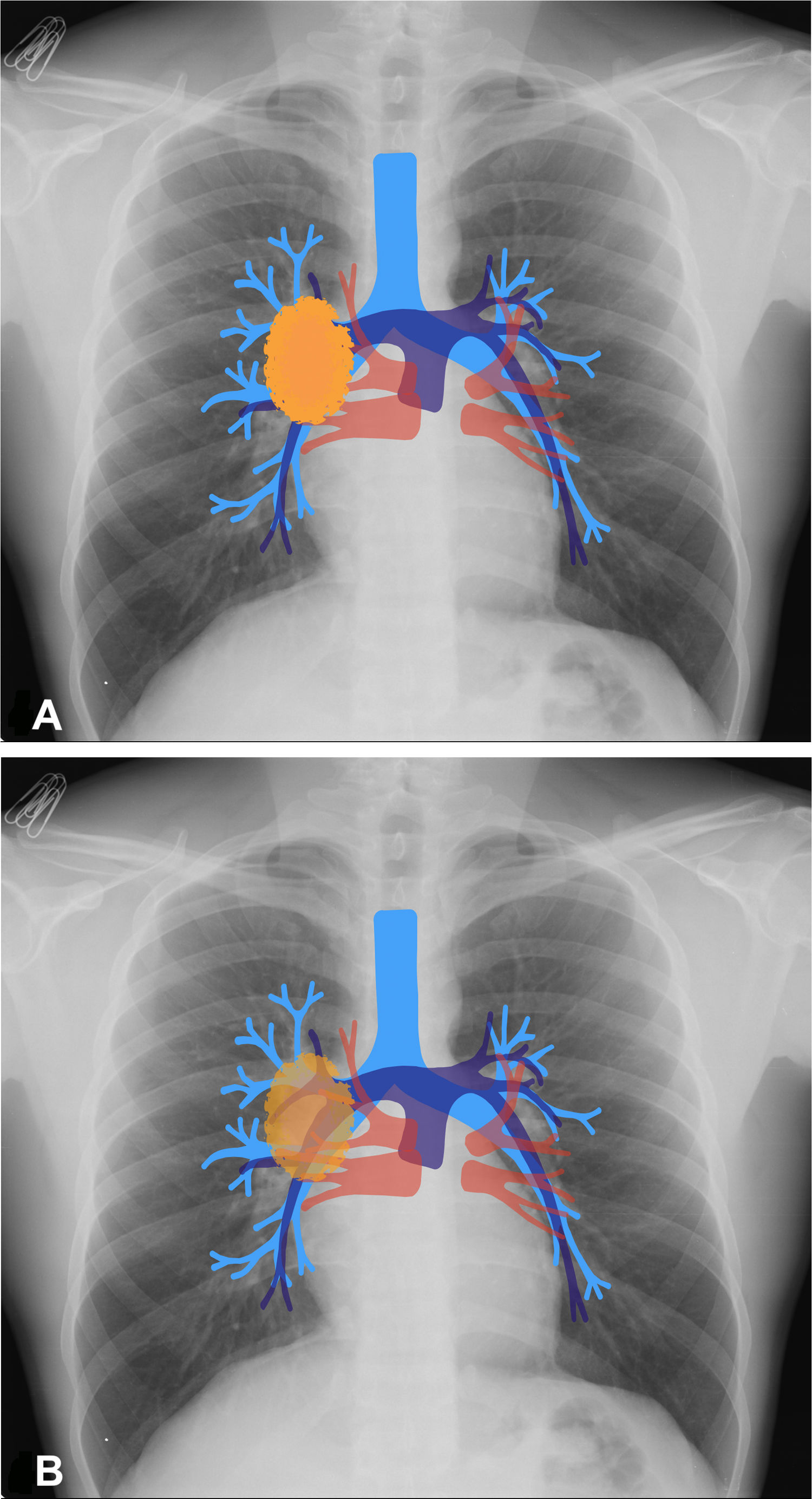

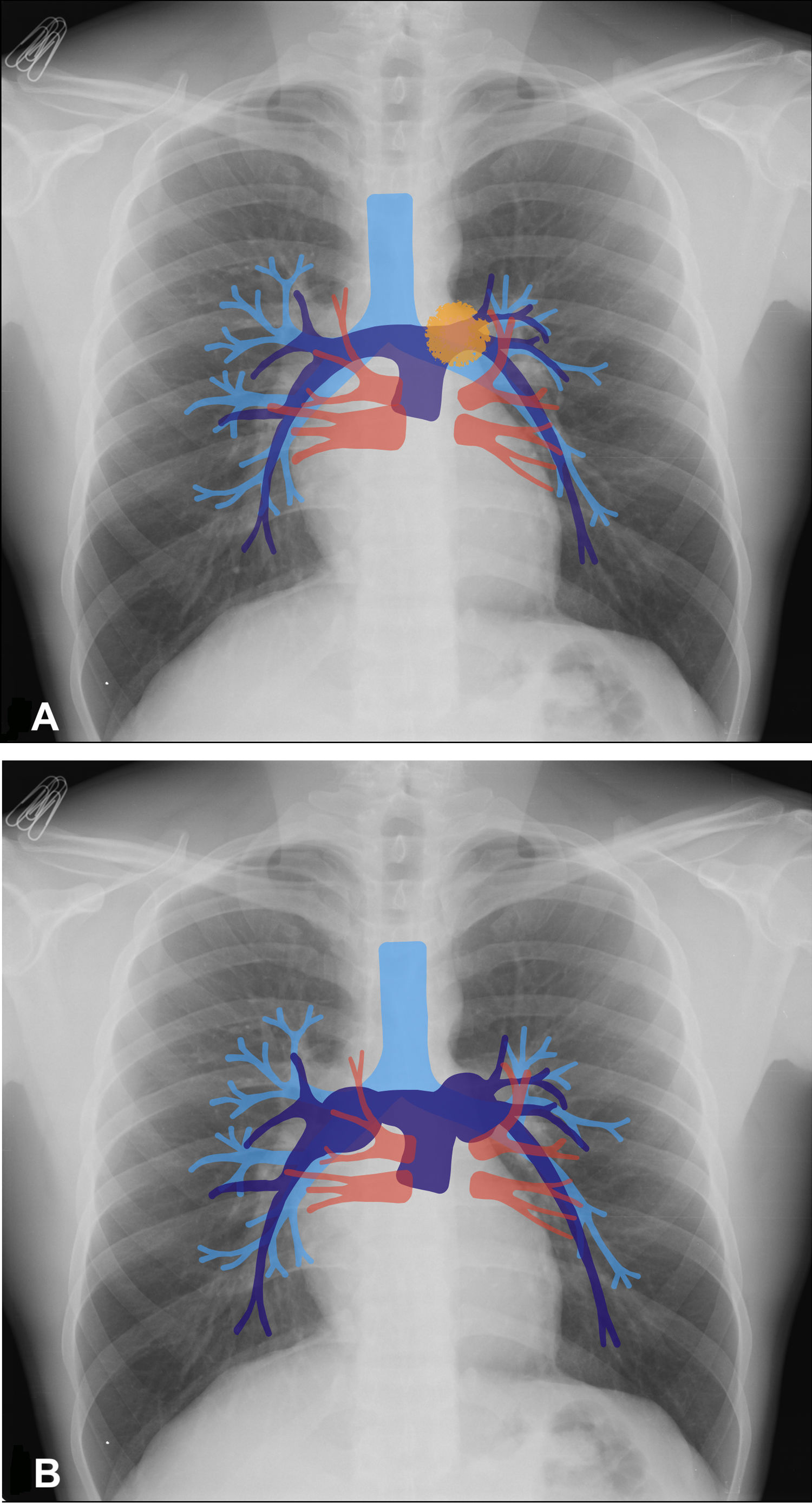

Anatomy of the hilumIn the anteroposterior view of the chest, the hila project in a "C" shape on either side.2 The right hilum is approximately 1–2cm lower than the left hilum, although in 3% of individuals the hila may be at the same level3 (Fig. 1A and B). This subtle finding could alert the clinician to a possible abnormality which is displacing or retracting the lung parenchyma (a high right hilum might suggest atelectasis of the right upper lobe). There is no benchmark size; some authors argue that measurements of the hilum are of uncertain value due to the large variations in the population: 84% of people have hila of the same size and 8% may have a longer right hilum.3 The density of the hilum is an important factor to assess; it should be similar to that of soft tissue and the heart. A comparative assessment should always be made; an increase in density may signal lymphadenopathy or masses in the area.3,6

Hilar anatomy on anteroposterior chest X-rays. 1 A) The “C” shape of the hila is shown with external convexity and attenuation similar to soft tissue. 1 B) Volumetric reconstruction of computed tomography superimposed on the X-ray, with the airway (blue), pulmonary veins (red) and arteries (purple). The formation of the venolobar angle (yellow dotted line) and that of the horizontal fissure (solid yellow line) are also seen.

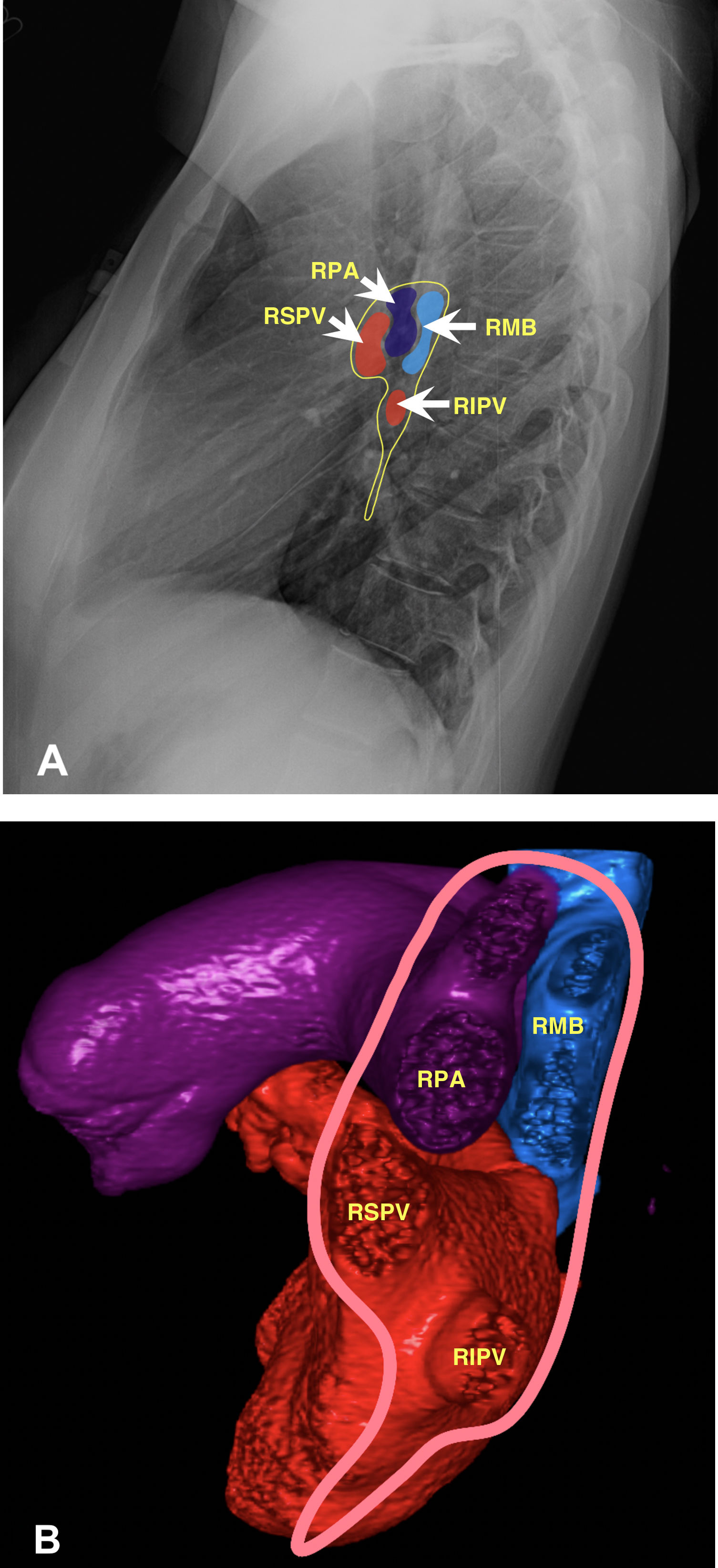

The right pulmonary artery (RPA) runs horizontally in front of the bronchus, which is consequently known as the eparterial bronchus. It divides within the mediastinum into an ascending (superior) and interlobar branch.3,4 The ascending branch runs obliquely and upwards towards the right upper lobe (RUL), supplying most of the pulmonary vasculature of this lobe3 (Fig. 2A and B).

Anatomy of the right hilum. 2 A) Chest X-ray in lateral view illustrating the normal anatomical relationships of veins, artery and bronchus. 2 B) Volumetric reconstruction of computed tomography. Delimitation of the pleural insertion of the right hilum (pink line) comprising bronchus (blue), veins (red) and pulmonary artery (purple). In the upper part the pulmonary artery is anterior and the bronchus posterior to that, while the pulmonary veins are in the inferior part. RPA: right pulmonary artery; RMB: right main bronchus; RIPV: right inferior pulmonary vein; RSPV: right superior pulmonary vein.

The right interlobar pulmonary artery (RIPA) continues horizontally along the axis of the RPA for 5–20mm with an oblique course, parallel to the lateral border of the middle lobe bronchus. This largely accounts for the shadow of the right hilum. However, it contributes little to the opacity of the upper part of the hilum as it branches within the mediastinum, and should not exceed 15–16mm in diameter.3–5 The RIPA narrows as it branches downwards into the middle lobe (ML) and the right lower lobe (RLL). Some branches called the pulmonary fissure arteries run towards the right upper lobe (RUL) and can originate from the angle between the horizontal and the descending part of the RIPA.3,4

The right superior pulmonary vein (RSPV) is found behind the hilar pulmonary arteries and overlaps them, forming the lateral margin of the right superior hilum. When this intersects with the pulmonary artery, a shallow external angle is formed called the "hilar point", which is usually greater than 90° (concave). Loss of concavity can often be suggestive of either a hilar mass or hilar lymphadenopathy. The medial portion of the horizontal fissure often ends at this point.3–6

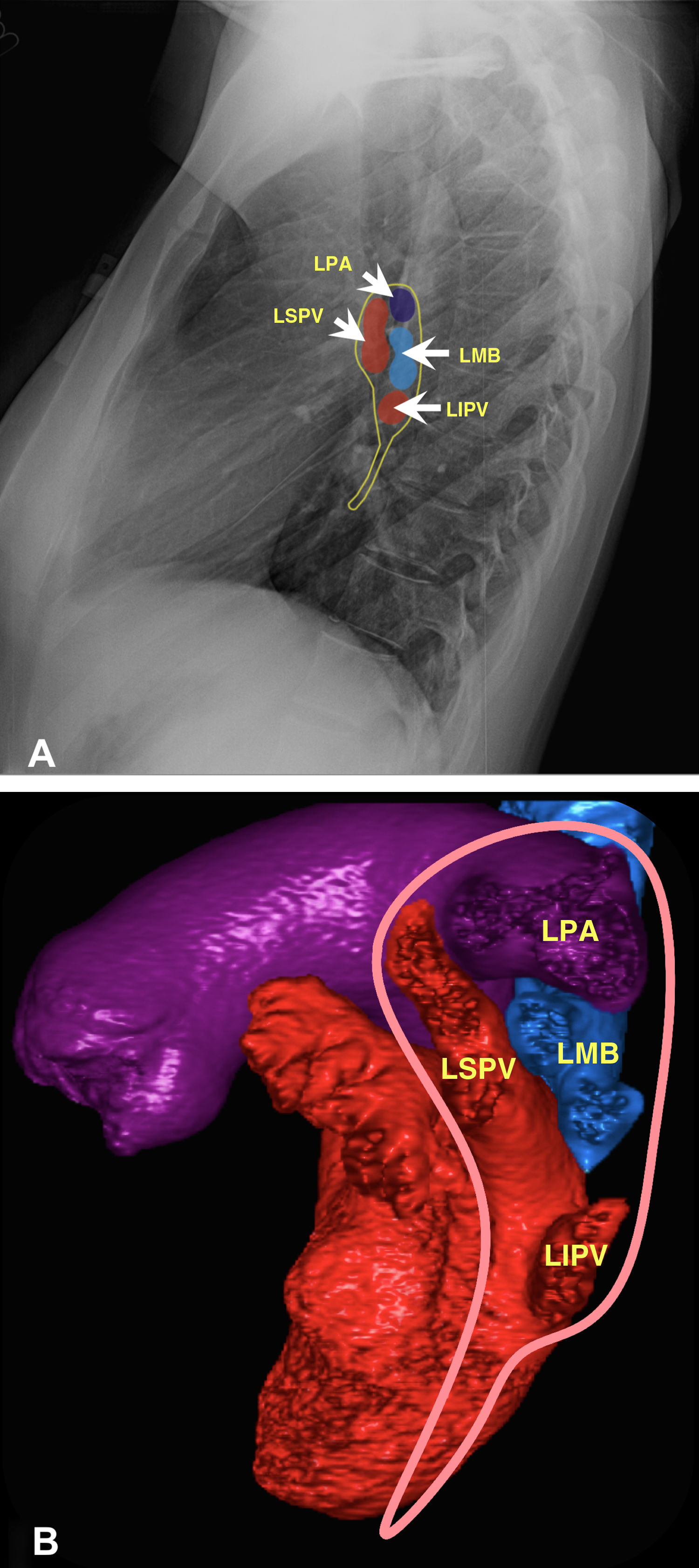

Left hilumOn the other side, the left pulmonary artery (LPA) arches over the left main bronchus, which is consequently known as the hyparterial bronchus. The LPA usually issues two or three small pulmonary arteries named after the pulmonary segment they supply; thereafter, it is called the left interlobar pulmonary artery (LIPA) and descends posterolaterally to the left lower lobe (LLL) bronchus.3–5 This vessel narrows and branches as it extends downwards, and is less visible than the contralateral vessel, due in part to the overlapping of the cardiac shadow. Similar to the right side, the left superior pulmonary vein (LSPV) is found behind the hilar pulmonary arteries and overlaps them3 (Fig. 3A and B).

Anatomy of the left hilum. 3 A) Chest X-ray in lateral projection illustrating the normal anatomical relationships of veins, artery and bronchus. 3 B) Volumetric reconstruction of computed tomography. Delimitation of the pleural insertion of the left hilum (pink line) to show its anatomical relationships, the pulmonary artery above the bronchus (epiarterial) and the left superior pulmonary vein (LSPV) in front of these. LPA: left pulmonary artery; LMB: left main bronchus; LIPV: left inferior pulmonary vein.

Utility: enables differentiation of a hilar lesion from a non-hilar lesion with the "silhouette sign”.4,7–9

Diseases in which it may be present:

- •

Neoplasms: thymic, lymphoma, germ cell tumour, lymphadenopathy.7,8

- •

Vascular lesions: pseudoaneurysms and aneurysms.7,8

Radiological appearance: this sign is established when the right or left pulmonary artery is visible more than 1cm within the lateral edge of the mediastinal silhouette; from that it can be deduced that the lesion is not cardiac enlargement.10,11 The hilum overlay sign is seen on anteroposterior chest X-rays and allows the location of a mass in the hilar region to be determined when the hilar vessels can clearly be seen through the lesion, being anterior or posterior to the hilum. If the hilar vessels cannot be distinguished from the lesion, the "silhouette sign" is produced and it can be deduced that the abnormality is in the hilum2,12–14 (Fig. 4).

Hilum overlay sign. 4 A) Diagram representing a mass in a hilar position (orange oval) erasing the view of the vessels. 4 B) Diagram showing a localised mass in an extrahilar position. The vessels can be seen through the lesion, but whether the lesion is in front of or behind the hilum cannot be determined.

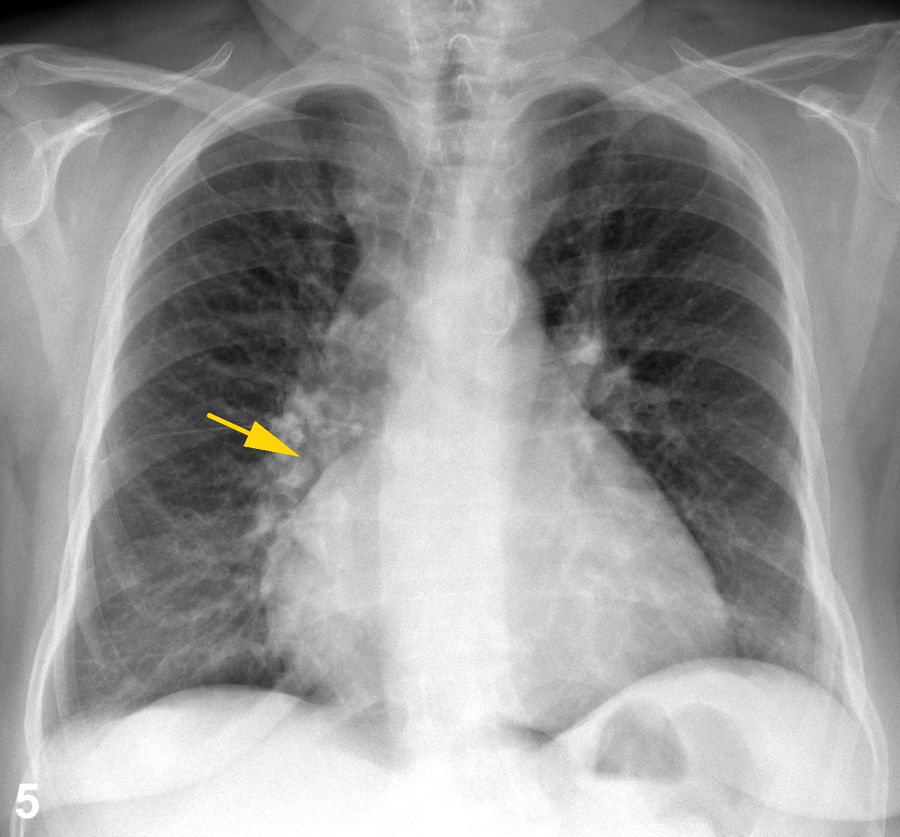

Normally, the main pulmonary arteries project outside or slightly overlapping the cardiac silhouette. In cardiomegaly, the anatomical relationship is maintained; the cardiac silhouette is enlarged and the main pulmonary arteries are displaced laterally, but do not overlap it12,15,16 (Fig. 5). However, when there is a mass in the anterior mediastinum, a radiopaque shadow is seen, making the "silhouette sign" with the heart, and if it is resting on it, it can seem like cardiomegaly, as the separation cannot be distinguished. As this mass does not displace the pulmonary hila laterally, the main pulmonary arteries are visible through it. Therefore, visualisation of any of the borders of the cardiac silhouette lateral to the ipsilateral pulmonary artery, at a distance greater than or equal to 1cm from it, indicates the presence of a mediastinal mass.10,11,17,18 When the edges of the pulmonary arteries are clearly identifiable, it can be assumed that the mass is anterior or posterior to the hilum19 (Fig. 6). The contour of the pulmonary artery is visible due to the adjacent aerated lung. When the aerated lung fills or is displaced, the edge of the pulmonary artery will no longer be detected (Fig. 7). An area of greater opacity anterior or posterior to the hilum has no effect on either the air adjacent to the pulmonary artery or its visibility. Felson (1968) described this phenomenon as the "hilum overlay sign".10,11 This is very helpful for separating true hilar abnormalities from overlapping shadows on the lung. In such cases, the lateral view is usually adequate to verify whether or not the abnormality is in the hilum. This differentiation is easily achieved with a CT scan.2,7

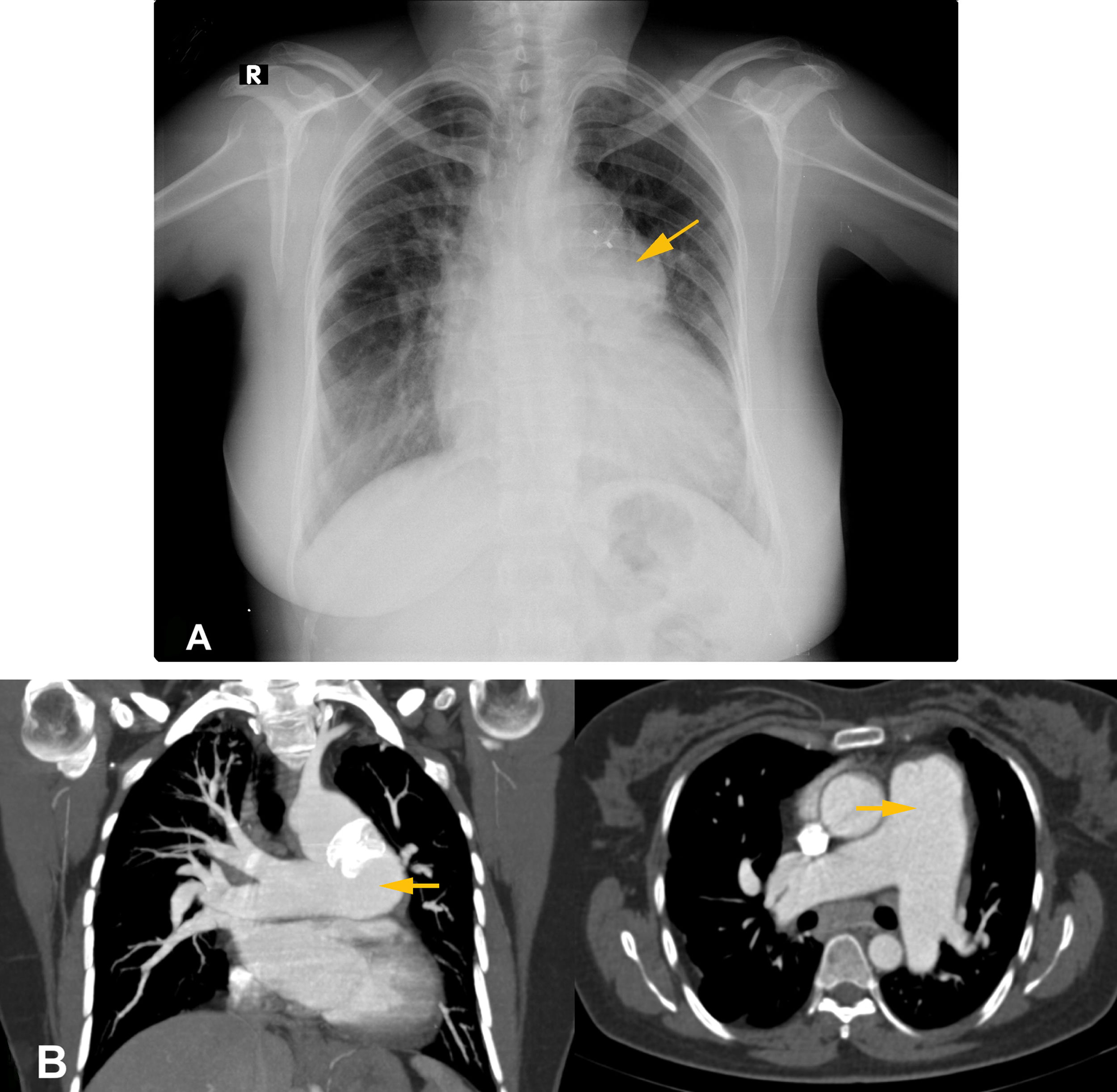

Posterior mediastinal mass in a 78-year-old woman. 6 A) Anteroposterior chest X-ray which allows the hilar vessels to be seen through the lesion without erasing their contours. It is inferred that the mass is not located in the hilum (yellow arrow). 6 B) Computed tomography with contrast of the chest on axial, coronal and sagittal planes, showing a solid, rounded mass with attenuation of soft tissues in contact with the spine and located in the posterior mediastinum (yellow arrows). Histopathology study showed a nerve sheath tumour.

Courtesy of Dr Lya Pensado, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias [Spanish Institute of Respiratory Diseases] (INER).

Cortesía de la Dra. Lya Pensado, INER.

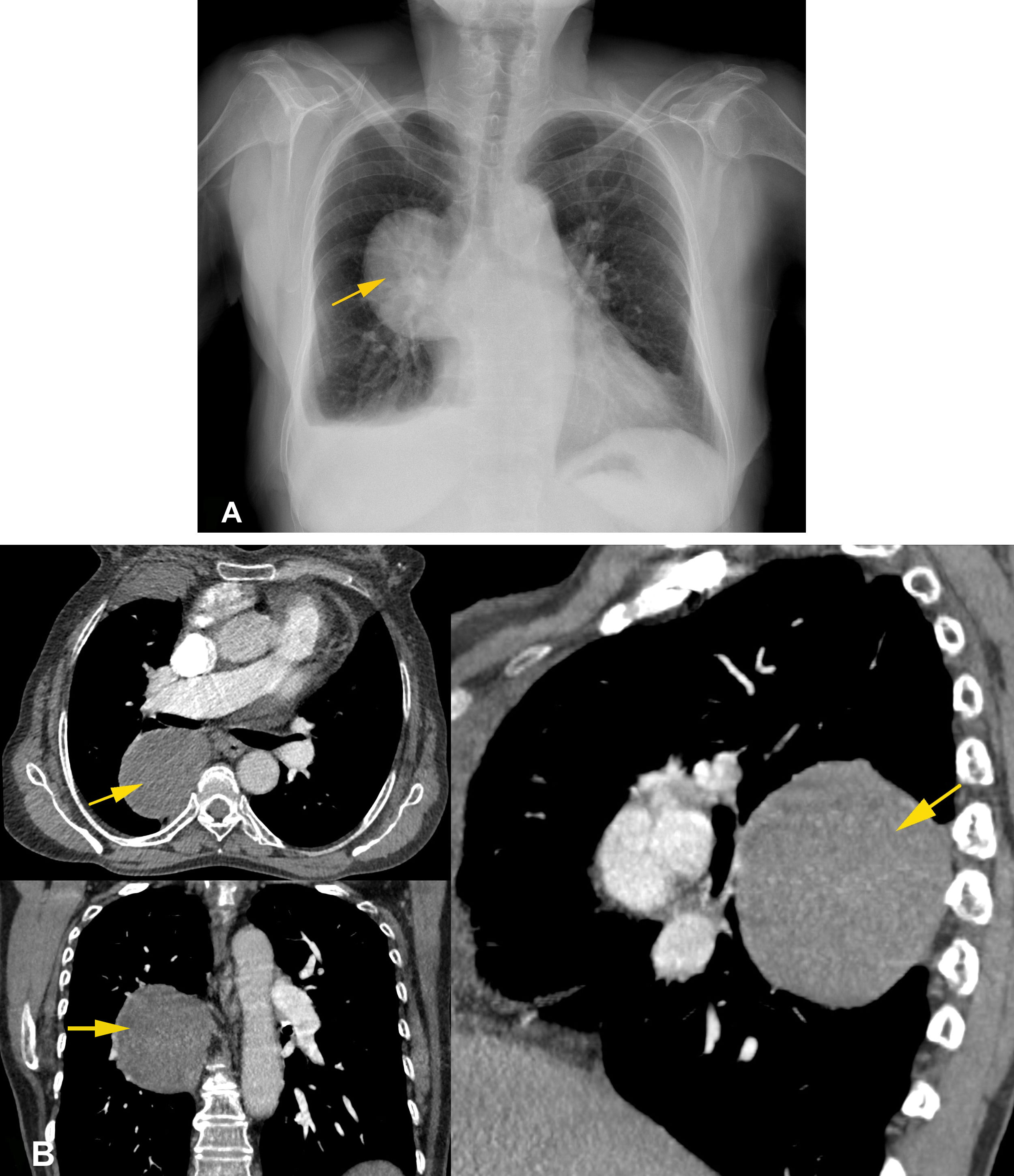

Hilar mass in a 62-year-old patient. 7 A) Anteroposterior chest X-ray showing a prominent and increased right hilum in which the hilar vessels cannot be distinguished from the lesion (white arrow). 7 B) Contrast computed tomography of the chest on axial, coronal and sagittal planes confirming the position of the lesion at the hilum, encompassing arteries, veins and bronchi (yellow arrows). Histopathology reported small-cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

Courtesy of Dr Lya Pensado, INER.

Utility: establishes the difference between hilar enlargement of vascular origin and a juxtahilar mediastinal mass.4,7,9

Diseases in which it may be present:

Radiological appearance: on an anteroposterior chest X-ray, it can be difficult to determine whether a hilar/juxtahilar shadow is due to a prominent pulmonary artery or juxtahilar mediastinal mass.17 If the pulmonary artery branches are visible through the shadow and converge towards the heart, then the shadow is due to a mediastinal mass located in front of or behind the hilum. However, if the pulmonary artery branches lead to an "abnormal" bulge, then the shadow is due to an enlarged pulmonary artery.11,17 (Fig. 8). The exception to this manner of identifying hilar enlargement of vascular origin is the case of infiltrative lesions of the hilum (Fig. 7); it is impossible to discern between an enlargement of the pulmonary artery (or one of its main branches) and this type of lesion. These findings should be interpreted in conjunction with the "hilum overlay sign", as this will help determine the possible location of the lesion in relation to the mediastinum.7,8

Hilum convergence sign. 8 A) Diagram showing a mass located in a left extrahilar position (orange oval). The branches of the pulmonary artery are visible through the shadow and seen to converge towards the heart, which indicates that the shadow is due to a mediastinal mass anterior or posterior to the hilum. 8 B) Diagram showing enlargement of the pulmonary arteries, where the branches end in hilar prominences of vascular origin.

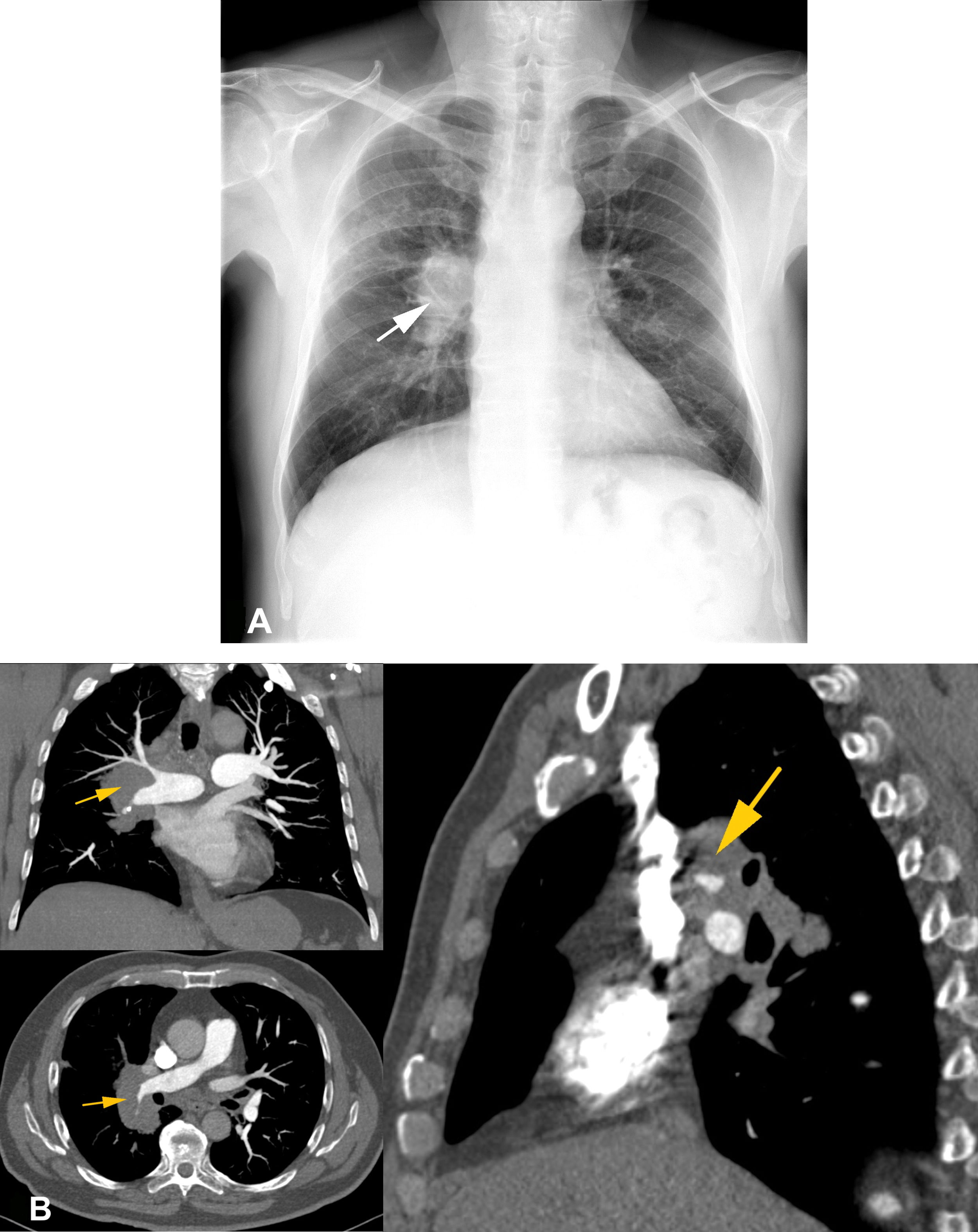

One challenge in evaluating a hilar abnormality is differentiating between a vascular enlargement and a hilar lesion — that is, distinguishing an enlarged pulmonary artery from a hilar mass which in many cases requires CT for confirmation. However, chest X-rays, as the first diagnostic method used for assessment of the thorax, offers important information in detecting changes in the contour of the hilar structures.3 At the level of the hilum, it is possible to differentiate its structures. However, some conditions such as pulmonary hypertension can dilate the pulmonary arteries, thus resembling a hilar mass. It is essential, therefore, to recognise such an increase in size in the main pulmonary artery, in order to be able to distinguish it from a shadow found at the hilum5,7,8 (Fig. 9). Felson stated that the proximal segment of the visible left pulmonary artery is lateral to or just inside the outer edge of the cardiac silhouette in over 98% of individuals, and just over 1cm inside the silhouette in all others.10,11,17 A similar situation occurs on the right side; even with pericardial effusion or cardiac enlargement, this relationship is maintained.15 If the branches of the pulmonary artery converge towards the mass rather than towards the heart, this suggests it is of a vascular nature: it is an enlarged pulmonary artery.9–11,17 The reverse suggests a mediastinal mass and reflects the "hilum overlay sign".

Eisenmenger syndrome in a 37-year-old woman with a patent ductus arteriosus. 9 A) Anteroposterior chest X-ray showing bulging of the left hilum with vessels leading to the "abnormal" bulge (yellow arrow). 9 B) Computed tomography angiogram in axial and coronal planes confirming vascular origin (yellow arrows).

It is extremely important to recognise that conventional chest X-rays remain very useful when investigating patients with cardiothoracic disease. It should always be borne in mind that the anatomical configuration and basic principles for radiological interpretation of the hilum will aid in analysing these difficult areas and reduce both the time and resources invested in assessing a patient. Both the "hilum overlay sign" and the "hilum convergence sign" are key elements in investigating changes in hilar density or enlargement. They are particularly useful for locating a lesion three-dimensionally on a flat image, in addition to separating true abnormalities from overlapping shadows on the lung.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Sources of fundingThis review received no specific grants from public agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Please cite this article as: Ludeña T, Lozano-Samaniego A, Maldonado S, Salas F. El hilio pulmonar, dos signos radiológicos clásicos para descifrarlo. Radiología.2022;64:60–68.

![Posterior mediastinal mass in a 78-year-old woman. 6 A) Anteroposterior chest X-ray which allows the hilar vessels to be seen through the lesion without erasing their contours. It is inferred that the mass is not located in the hilum (yellow arrow). 6 B) Computed tomography with contrast of the chest on axial, coronal and sagittal planes, showing a solid, rounded mass with attenuation of soft tissues in contact with the spine and located in the posterior mediastinum (yellow arrows). Histopathology study showed a nerve sheath tumour. Courtesy of Dr Lya Pensado, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias [Spanish Institute of Respiratory Diseases] (INER). Cortesía de la Dra. Lya Pensado, INER. Posterior mediastinal mass in a 78-year-old woman. 6 A) Anteroposterior chest X-ray which allows the hilar vessels to be seen through the lesion without erasing their contours. It is inferred that the mass is not located in the hilum (yellow arrow). 6 B) Computed tomography with contrast of the chest on axial, coronal and sagittal planes, showing a solid, rounded mass with attenuation of soft tissues in contact with the spine and located in the posterior mediastinum (yellow arrows). Histopathology study showed a nerve sheath tumour. Courtesy of Dr Lya Pensado, Instituto Nacional de Enfermedades Respiratorias [Spanish Institute of Respiratory Diseases] (INER). Cortesía de la Dra. Lya Pensado, INER.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/21735107/0000006400000001/v2_202202200527/S2173510720301129/v2_202202200527/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr6.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)