The current management of acute diverticulitis of the left colon (ADLC) requires tests with high prognostic value. This paper analyzes the usefulness of ultrasonography (US) in the initial diagnosis of ADLC and the validity of current classifications schemes for ADLC.

PatientsThis retrospective observational study included patients with ADLC scheduled to undergo US or computed tomography (CT) following a clinical algorithm. According to the imaging findings, ADLC was classified as mild, locally complicated, or complicated. We analyzed the efficacy of US in the initial diagnosis and the reasons why CT was used as the first-line technique. We compared the findings with published classifications schemes for ADLC.

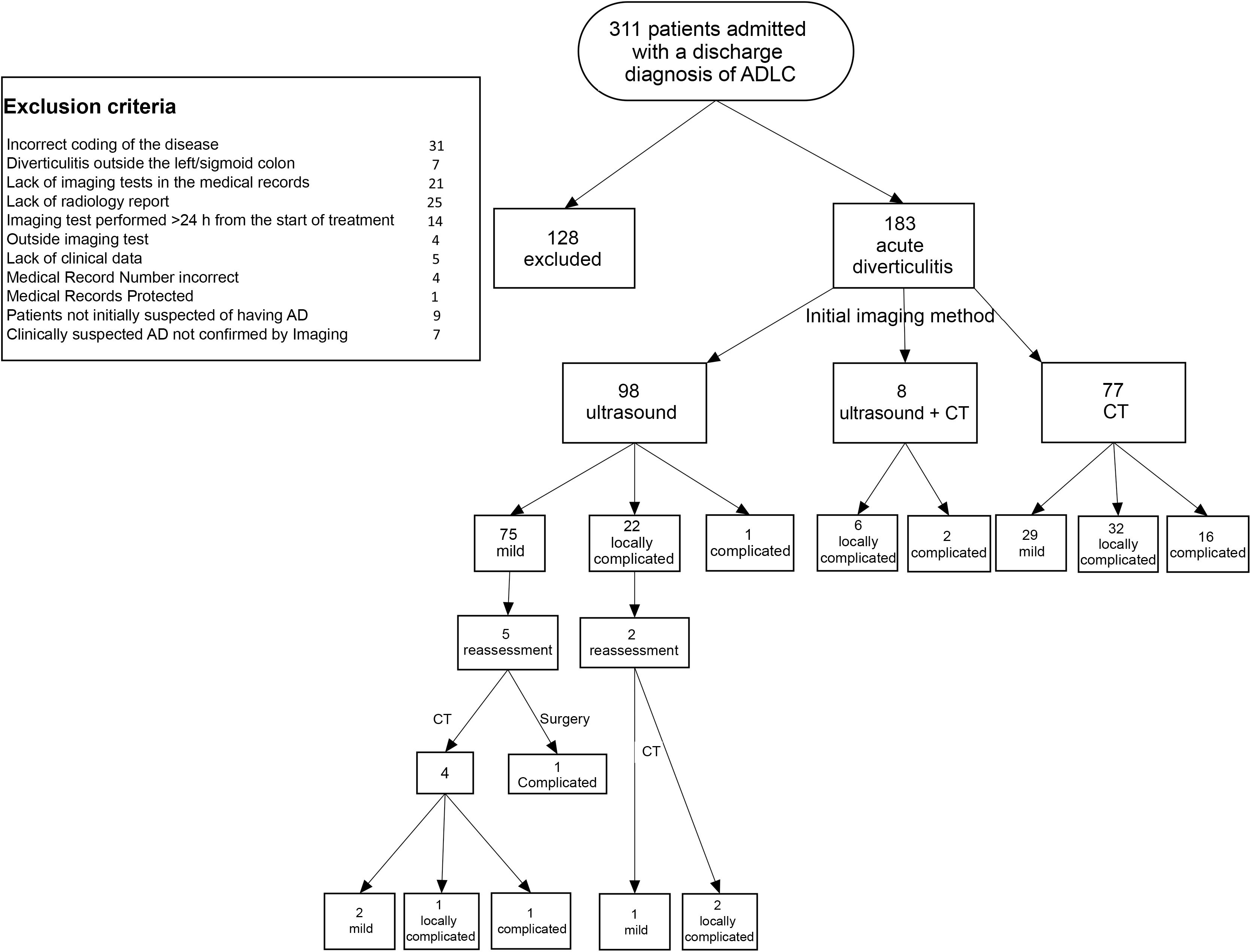

ResultsA total of 311 patients were diagnosed with acute diverticulitis; 183 had ADLC, classified at imaging as mild in 104, locally complicated in 60, and complicated in 19. The diagnosis was reached by US alone in 98 patients, by CT alone in 77, and by combined US and CT in 8. The main reasons for using CT as the first-line technique were the radiologist’s lack of experience in abdominal US and the unavailability of a radiologists on call. Six patients diagnosed by US were reexamined by CT, but the classification changed in only three. None of the published classification schemes included all the imaging findings.

ConclusionsUS should be the first-line imaging technique in patients with suspected ADLC. Various laboratory and imaging findings are useful in establishing the prognosis of ADLC. New schemes to classify the severity of ADLC are necessary to ensure optimal clinical decision making.

El manejo actual de la diverticulitis aguda de colon izquierdo requiere pruebas con alto valor pronóstico. Los objetivos del estudio son analizar la utilidad de la ecografía como método diagnóstico inicial y evaluar la validez de las clasificaciones actuales de gravedad de dicha enfermedad.

PacientesEstudio observacional retrospectivo de pacientes con diverticulitis aguda de colon izquierdo. Se solicitó ecografía o tomografía computarizada (TC) siguiendo un algoritmo clínico. Tras los hallazgos de imagen, se clasificó la enfermedad como leve, localmente complicada y complicada. Se evaluaron la eficacia de la ecografía como herramienta diagnóstica inicial y las razones por las que se realizó una TC como técnica inicial. Se compararon los hallazgos con las clasificaciones de diverticulitis publicadas.

ResultadosDe 311 pacientes con diverticulitis aguda, se seleccionaron 183 con diverticulitis aguda de colon izquierdo, que fueron clasificadas por imagen como leves (104), localmente complicadas (60) y complicadas (19). En 98 pacientes, el diagnóstico se realizó por ecografía, en 77 por TC y en 8 mediante ambas. Las principales razones de utilización inicial de TC fueron falta de experiencia del radiólogo en ecografía abdominal y falta de disponibilidad de un radiólogo de guardia. A 6 pacientes diagnosticados por ecografía se les realizó una nueva evaluación por TC, pero solo en 3 cambió la clasificación. Ninguna de las clasificaciones publicadas recoge todos los hallazgos en imagen.

ConclusionesLa ecografía debería ser la primera técnica a utilizar para el diagnóstico de diverticulitis aguda de colon izquierdo. Para establecer el pronóstico de la enfermedad, son útiles diversos parámetros analíticos y hallazgos de imagen. Para una apropiada toma de decisión terapéutica se necesitarían nuevas clasificaciones de gravedad.

In Western countries, the prevalence of diverticular disease of the colon is 5% at 40 years of age and 65% in the over-80 s.1,2 Some 10–20% of patients with diverticulosis will have at least one episode of acute diverticulitis,3,4 which in the West mainly occurs in the left colon.2 Acute diverticulitis of the left colon (ADLC) can be classified as mild or uncomplicated, and complicated, with 75% of cases being uncomplicated.3,5,6

Its therapeutic management depends on the severity and can range from conservative (antibiotic and/or anti-inflammatory treatment) to percutaneous drainage or surgery. There is ongoing debate as to the most appropriate method of identifying mild cases that can be treated on an outpatient basis, or which can be treated with anti-inflammatories, avoiding antibiotics.5,7–10

In two thirds of patients, a presumptive diagnosis can be reached with clinical criteria,11 although imaging techniques are always required for confirmation. Ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) are the most used, but there is a lack of consensus on which is the first-line technique of choice.12

Various grading systems based on surgical or CT findings have been developed for determining the severity of ADLC, which have been modified as advances have been made in the diagnosis and treatment of the disease.13,14 The Hinchey classification (1978),15 based on the Hughes classification (1963),16 focuses primarily on the location of the abscesses. It was supplemented by Sher (1997)17 and Wasvary (1999).18 The HS classification (Hansen and Stock, 1999)19 has been the main one used in Germany, while in other countries the Neff classification (1989)20 is preferred. Siewert (1995),21 Ambrosetti (2002)22 and Tursi (2008)23 suggested simplified classifications, while a Dutch group argues for one with more complexity (Klarenbeck, 2012).14 In 2005, Kaiser presented a classification based on the clinical severity and form of presentation of the disease.24 Subsequently, the modified Neff classification25 and the 2015 consensus guidelines of the German societies emerged, which proposed distinguishing uncomplicated diverticulitis from complicated diverticulitis and chronic diverticular disease.26

The aims of this study were: a) to analyse the validity of ultrasound in the initial diagnosis of diverticulitis; and b) to determine the adequacy of some of the current classifications in assessing the severity and prognosis of this disease.

Material and methodsThis was a retrospective observational study of patients diagnosed with ADLC requiring hospital admission. The study was approved by the independent ethics committee, which determined that an informed consent form was not necessary. Patients who met all the following criteria were initially included: main discharge diagnosis of acute diverticulitis; performance of an urgent imaging test (ultrasound, CT or both); and confirmation of acute diverticulitis by imaging technique. Patients were then excluded who were not initially viewed as suspected ADLC and in whom the imaging test was requested with another presumptive diagnosis. The rest of the exclusion criteria are shown in Fig. 1. All imaging tests were performed urgently. The imaging tests were carried out by six radiologists with more than five years’ experience as specialists. Three of them were specialists in abdominal radiology and the other three in other areas, although with previous generic training in ultrasound and abdominal CT.

From 2009 to 2014, the ultrasounds were performed with Acuson Antares equipment (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) with a 4-1 MHz convex probe and a 5−10 MHz linear probe. From 2015 on, an Aplio 500 (Toshiba, Minato, Tokyo, Japan) was used with a 3.5 MHz convex probe and a 7 MHz linear probe. All patients underwent ultrasound of the entire abdomen and pelvis with a convex probe, and of the painful area (left iliac fossa and/or hypogastrium) with both probes. All CT scans were performed with a Somatom Emotion 6-slice model (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The slice thickness used was 3.0 mm with a 1.5 pitch. The studies were performed after administration of intravenous contrast (Ultravist 300 mg/mL; Bayer Hispania, S.L., Sant Joan Despí, Spain) and in some cases with positive oral contrast (Gastrografin 370 mg iodine/mL; Bayer Hispania, S.L., Sant Joan Despí, Spain).

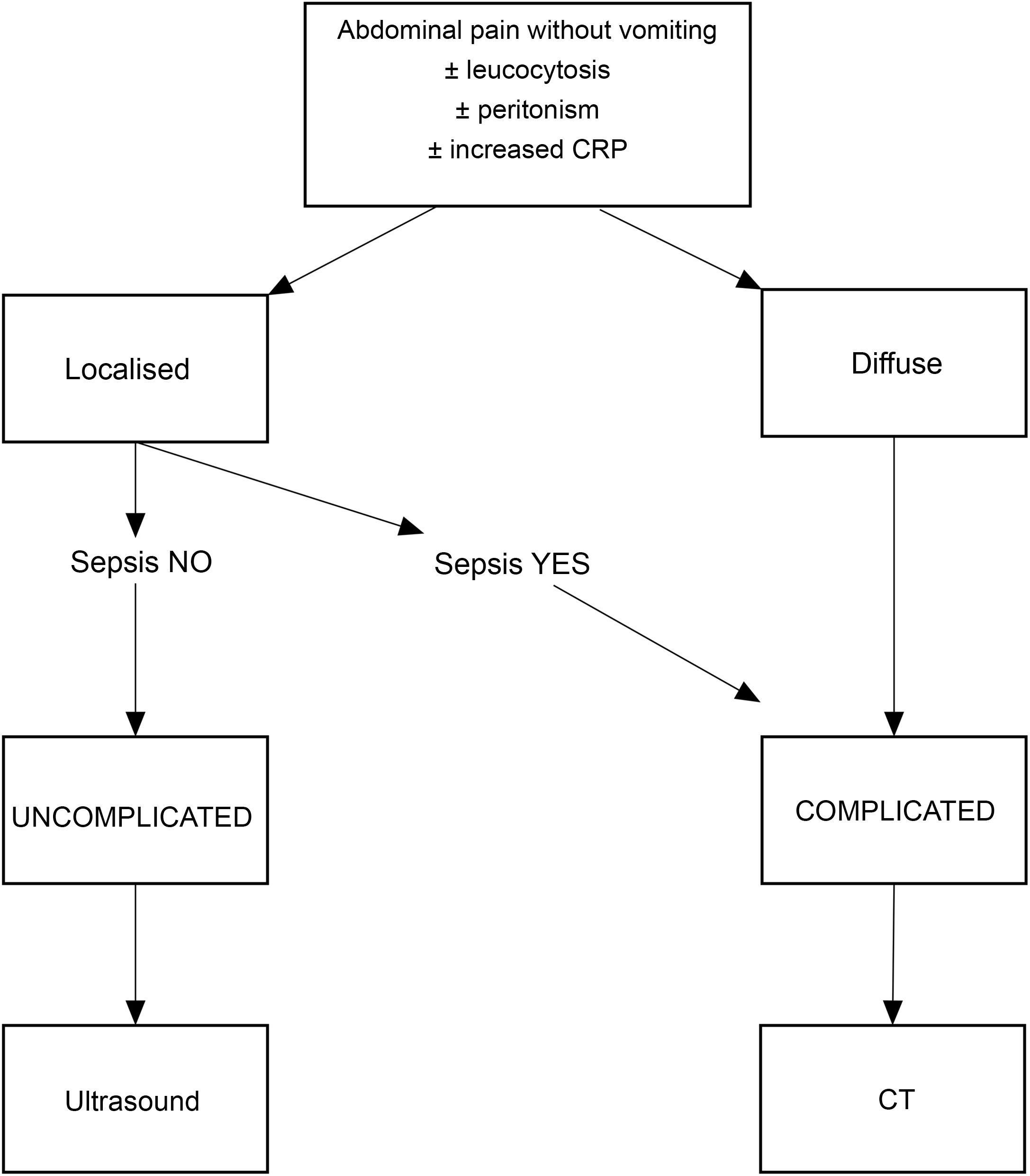

An algorithm based on clinical and analytical criteria (Fig. 2) was used to classify suspected ADLC as uncomplicated or complicated. This hospital diagnostic protocol was based on the modification of criteria previously described by other authors.27,28 According to this algorithm, for localised and presumably uncomplicated diverticulitis, the recommendation was to request an ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis. The final decision on ultrasound or CT was at the discretion of the radiologist, and the reasons for any deviation from the protocol, if stated, were recorded.

The diagnosis of ADLC, both by CT and by ultrasound, was based on six criteria: wall thickening in the painful segment (>4 mm); presence of diverticula or pericolic or peri-diverticular phlegmon (increased echogenicity of peri-diverticular and/or pericolic fat); presence of an adjacent fluid band or minimal pelvic fluid band; presence of focal pneumoperitoneum; and presence of local abscesses. In the ultrasound studies, the findings used to assess the presence of inflammation or mural oedema were hypoechogenic mural thickening of the colon or of the wall of the diverticula affected by the inflammatory process and loss of definition of the mural layers. Both techniques looked for the presence of distant abscesses, free fluid in other regions and diffuse pneumoperitoneum as standard practice.

Demographic, clinical and analytical data were collected from the medical records. The imaging findings were obtained from the diagnostic tests through the reports issued. None of the cases was subject to a subsequent review of the images or rectification of the report. The type of diagnostic test performed initially (ultrasound, CT or both) was recorded. Where CT was chosen as the first-line imaging technique or both techniques were performed, the reasons that led to this practice were recorded. Information was also obtained on the treatment received, the presence of complications during admission, the need for further examinations and the length of hospital stay. Although some of the classifications are based on surgical findings, to compare radiological findings, we used the classifications previously used at the centre: Hinchey, modified Hinchey, Neff and modified Neff,15,18,20,25 the modified Neff being current practice (Table 1).

Diagnostic criteria and stages of the acute diverticulitis classifications used in the study.

| Staging | Hinchey15 | Modified Hinchey18 | Neff20 | Modified Neff25 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Mild clinical diverticulitis | Uncomplicated diverticulitis. Diverticula, bowel wall thickening, increased pericolic fat | Uncomplicated diverticulitis. Diverticula, bowel wall thickening, increased pericolic fat | |

| I | Pericolic abscess/phlegmon | Locally complicated diverticulitis. Abscess <4 cm | Locally complicated diverticulitis | |

| Ia | Pericolic inflammation/phlegmon | Localised pneumoperitoneum in the form of gas bubbles | ||

| Ib | Pericolic abscess | Abscess <4 cm | ||

| II | Pelvic, intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal abscess | Pelvic, intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal abscess | Abscess >4 cm | Abscess >4 cm |

| III | Generalised purulent peritonitis | Generalised purulent peritonitis | Complicated diverticulitis with distant abscesses (outside the pelvic cavity) | Complicated diverticulitis with distant abscesses (outside the pelvic cavity) |

| IV | Generalised faecal peritonitis | Generalised faecal peritonitis | Diffuse pneumoperitoneum or intra-abdominal free fluid | Diffuse pneumoperitoneum or intra-abdominal free fluid |

In addition, we reviewed different classifications of acute diverticulitis to assess their degree of adaptation to the series, including those by Sher,17 Wasvary,18 Hansen and Stock,19 Siewert,21 Ambrosetti,22 Tursi,23 Klarenbeck,14 Kaiser,24 Bucley28 and the Consensus Guidelines of the German Societies of Radiology, Surgery and Gastroenterology.29

For statistical analysis, ADLC was classified as mild, locally complicated or complicated, based on the modified Neff classification. The presence of diverticula, bowel wall thickening (>4 mm) and/or peridiverticular or pericolic phlegmon was considered as mild ADLC. The diverticulitis was considered locally complicated when, in addition, fluid appeared but confined to the left iliac fossa (LIF) or pelvis, and/or focal pneumoperitoneum and/or abscess smaller than 4 cm. Complicated diverticulitis was defined as the presence of an abscess larger than 4 cm, multiple abscesses, abscesses beyond the LIF, free abdominal fluid and diffuse pneumoperitoneum. The classification of severity by imaging was used to establish comparisons of demographic and medical data.

The information obtained was collated in a database specially designed for the study (Limia®), to which only the principal investigator and the data analyst had access.

A statistical package for Health Sciences (IBM SPSS 24®) was used to process the data. For the statistical study, Pearson’s χ2 tests were used for categorical variables and Student's t-test to compare medians in continuous variables. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

ResultsA total of 311 patients who met the inclusion criteria were assessed, 128 of whom were rejected for the reasons stated in the study flowchart (Fig. 1). There were no cases of outpatient management. All patients were treated with anti-inflammatories and antibiotics at the beginning. Surgery as treatment accounted for only 3% of the series.

Of the 183 patients finally studied, from a medical and analytical point of view 165 were considered to be uncomplicated ADLC and 18 complicated. The signs and symptoms they exhibited are shown in Table 2 and the demographic results in Table 3.

Clinical and analytical results of the series.

| Form of presentation | Patients (%) |

|---|---|

| N = 183 | |

| Abdominal pain in the left iliac fossa or hypogastrium | 183 (100%) |

| Peritoneal irritation/peritonism | 28 (15.3%) |

| Palpable mass | 12 (6.5%) |

| Fever (>38°C) | 19 (10.4%) |

| Leucocytosis >12,000 | 114 (62.3%) |

| Leucopenia <4000 | 0 |

| CRP >0.1 mg/dl | 183 (100%) |

CRP: C-reactive protein.

| Mild | Locally complicated | Complicated | Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 104 (%) | n = 60 (%) | (n = 19) (%) | n = 183 (%) | ||

| Gender | NS | ||||

| Male | 67 (64.4) | 32 (53.3) | 11 (57.9) | 110 (60.1) | |

| Female | 37 (35.6) | 28 (46.7) | 8 (42.1) | 73 (39.9) | |

| Mean age (SD) | 57.4 (13.9) | 55.5 (13.5) | 59.7 (11.8) | 57 (13.6) | NS |

| Days in hospital: mean (SD) | 5.6 (6.3) | 6.8 (3.9) | 11.4 (5.8) | 6.6 (5.8) | <0.001 |

| Leucocytosis: mean (SD) | 12,859 (4743) | 14,103 (3111) | 15,353 (3856) | 13,521 (4258) | <0.01 |

| CRP: mean (SD) | 38.3 (43.6) | 20.8 (32.7) | 33.2 (34.4) | 32.0 (40.2) | <0.01 |

| SIRS criteria | NS | ||||

| No | 88 (84.6) | 47 (78.3) | 13 (68.4) | 148 (80.9) | |

| Yes | 11 (10.6) | 9 (15.0) | 6 (31.6) | 26 (14.2) | |

| No. of SIRS criteria | NS | ||||

| 0 | 34 (32.6) | 15 (25.0) | 3 (15.7) | 6 (4.4) | |

| 1 | 60 (57.6) | 36 (60.0) | 10 (52.6) | 106 (77.4) | |

| 2 | 8 (7.6) | 8 (37.3) | 6 (31.5) | 22 (16.1) | |

| 3 | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.6) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (2.2) | |

| Ultrasound | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 28 (26.9) | 38 (63.3) | 17 (89.5) | 83 (45.4) | |

| Yes | 76 (73.1) | 22 (36.7) | 2 (10.5) | 100 (54.6) | |

| CT | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 75 (72.1) | 16 (26.7) | 1 (5.3) | 92 (50.3) | |

| Yes | 29 (27.9) | 44 (73.3) | 18 (94.7) | 91 (49.7) | |

p-value (NS): not significant.

CRP: C-reactive protein; CT: computed tomography; SD: standard deviation; SIRS: systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Based on the radiological findings, 104 patients were reclassified as mild ADLC, 60 as locally complicated and 19 as complicated. Table 3 shows the comparison of results between these groups. There were no significant differences in the degree-of-severity distribution by gender, age or presence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). There was a significant increase in leucocytosis and hospital stay as the severity of the ADLC increased. There was a higher prevalence of SIRS in the most serious patients, but without statistical significance. CRP levels were elevated in all three groups, with significant differences between them, but with no correlation to severity.

Initial diagnosis by imaging. The initial diagnosis was reached by ultrasound (US) alone in 98 patients (53.6%), by CT alone in 77 (42.0%), and by combined US and CT in 8 (4.4%) (Fig. 1). The reason for performing both techniques in the initial diagnosis (first ultrasound and then CT) was: the need to confirm ultrasound findings due to the radiologist’s lack of experience (n = 2); ultrasound technical difficulty (n = 2); ultrasound inconclusive according to an expert radiologist (n = 1); findings suggesting severity in the initial ultrasound (n = 2); and not recorded in the medical records (n = 1).

Overall, CT was used as the first-line technique in 85 patients (in 77 as the only examination and in 8 in combination with ultrasound), the main reasons being the lack of an expert radiologist in abdominal ultrasound or the absence of a physically present radiologist (55.4%). All the reasons for CT being used as the first-line diagnostic technique are shown in Table 4.

Reasons for using computed tomography (CT) as the first imaging test.

| Mild AD | Locally complicated AD | Complicated AD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 104) | (n = 60) | (n = 19) | |

| Initial CT | 29 (26.6%) | 38 (63%) | 16 (84.2%) |

| Lack of an expert radiologist in abdominal ultrasound | 15 | 18 | |

| Lack of on-call radiologist on site | 8 | 5 | |

| Clinical diagnosis of diverticulitis questionable | 4 | 10 | 1 |

| Suspected clinical severity | 2 | 3 | 15 |

| Reason not stated | 2 |

AD: acute diverticulitis.

There were no statistical differences between the use of CT or ultrasound for the initial diagnosis of ADLC in terms of hospital stay in the cases of mild and locally complicated ADLC. This analysis could not be performed in the complicated ADLC group due to the small number of patients and because all but one were diagnosed by CT.

Significant differences were found in the use of ultrasound or CT as first-line diagnostic techniques for ADLC according to its severity, with ultrasound being used more in diverticulitis clinically classified as uncomplicated and CT in those classified as complicated (Table 3).

Of the 104 patients diagnosed by imaging as mild ADLC, 75 were diagnosed by ultrasound and 29 by CT. Of the 60 patients classified as locally complicated ADLC, the initial diagnosis was made by ultrasound only in 22, by CT only in 32 and with the combination of the two techniques in 6. Of the 19 patients diagnosed with complicated ADLC, 16 were initially diagnosed by CT alone, 1 by ultrasound alone and 2 with both techniques (Fig. 1).

Utility of ultrasound. The overall rate for reassessment by CT of the patients initially diagnosed by ultrasound was low (7.1%). Of the 75 patients initially diagnosed by ultrasound as mild diverticulitis, five were reassessed during admission, one clinically and four by CT. Of the those four, the mild classification was maintained in two, one was reclassified as locally complicated and the other as complicated. The patient reassessed clinically underwent surgery without imaging tests due to sigmoid colon perforation and diffuse peritonitis.

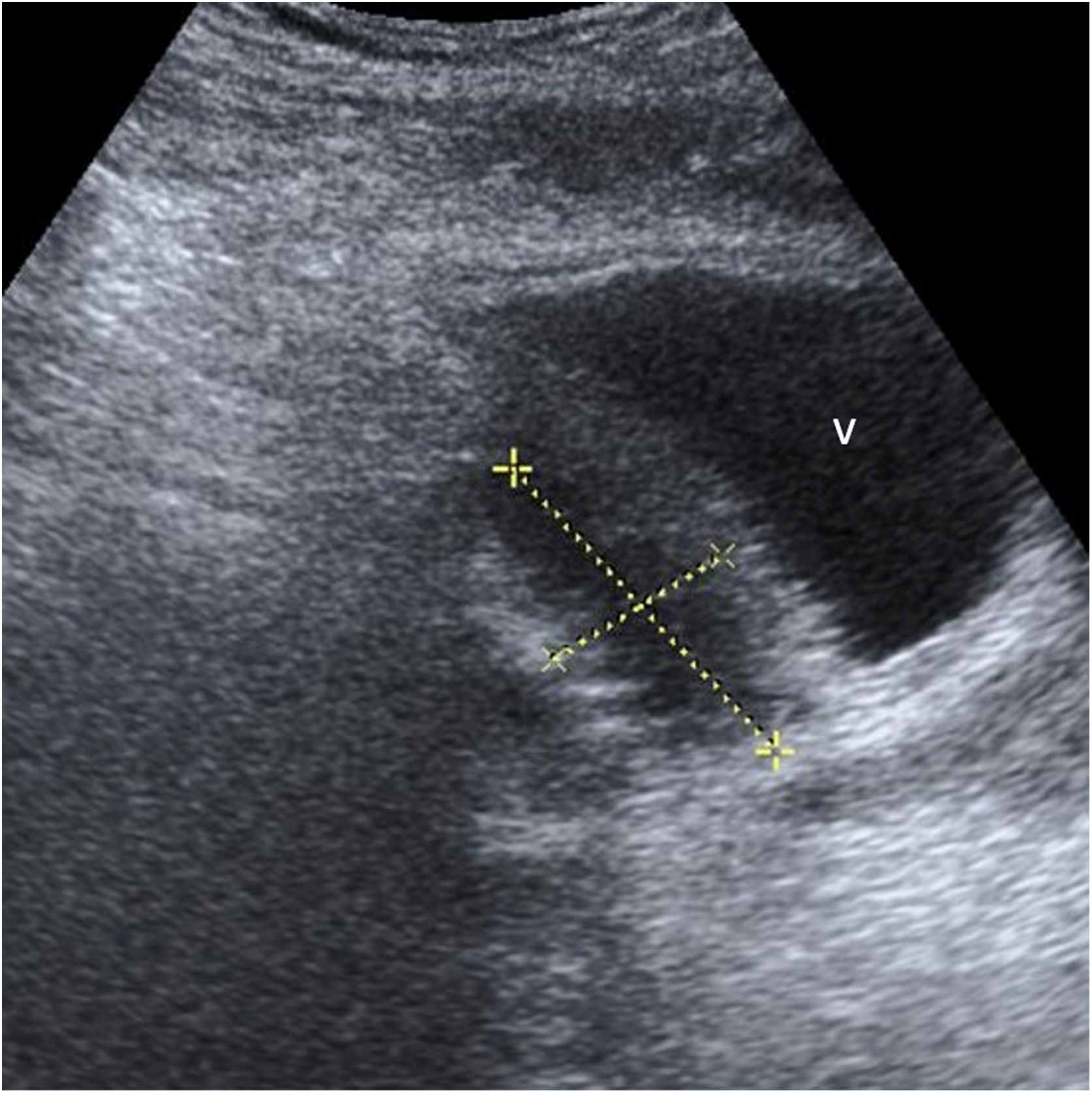

Of the 22 patients diagnosed by ultrasound with locally complicated ADLC, only two required reassessment by CT, observing radiological improvement of the findings in one and stability of the findings in the other. Of the six patients with ultrasound as first-line technique who simultaneously had a CT, the CT confirmed the same findings as ultrasound in four (locally complicated in both techniques) (Fig. 4).

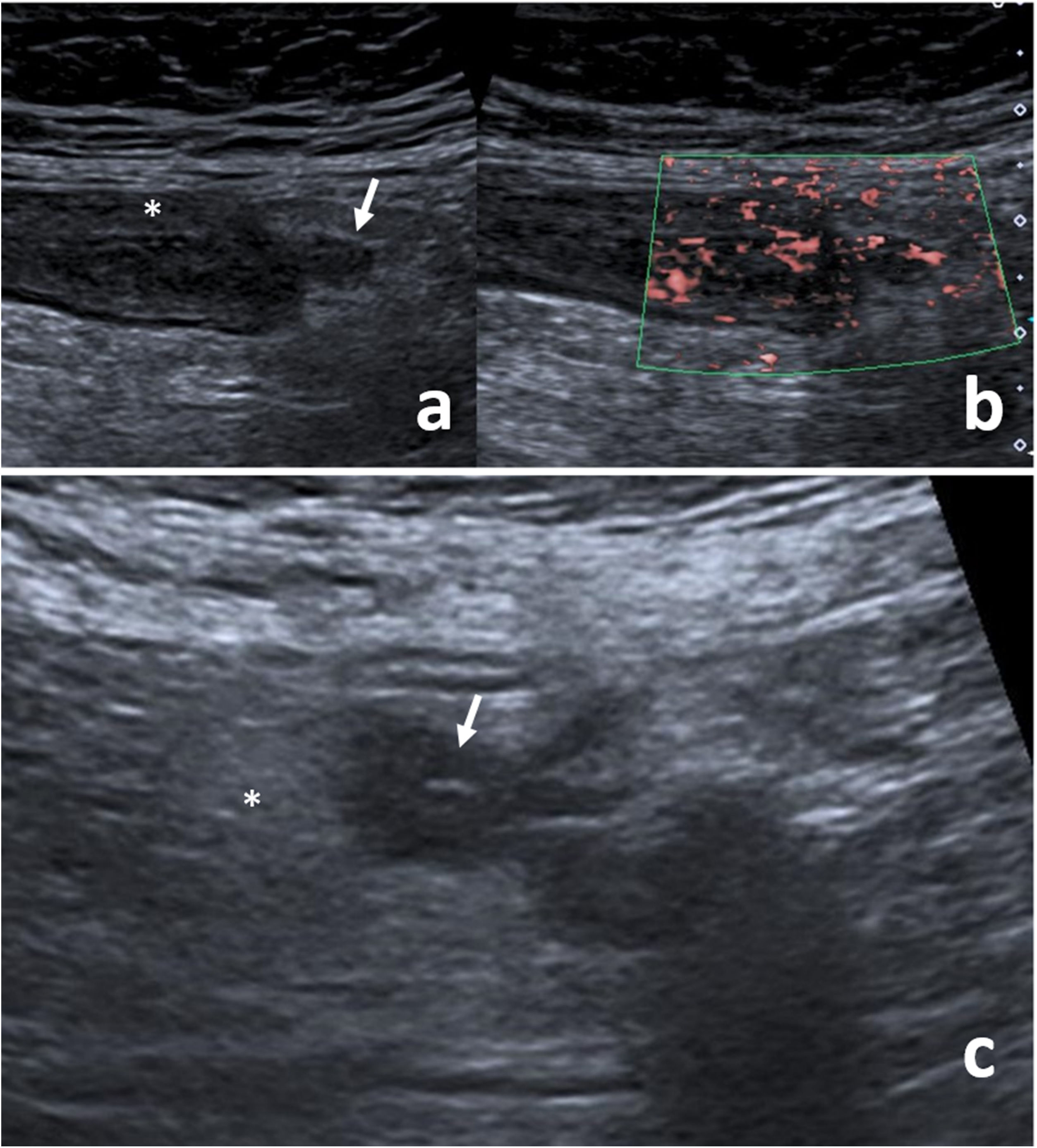

The only patient diagnosed by ultrasound as complicated ADLC showed localised pneumoperitoneum and free peritoneal fluid, with these findings later confirmed by surgery. The main ultrasound findings are shown in Figs. 3 and 5.

Ultrasound image of mild acute diverticulitis of the left colon. (A) A collapsed colon segment with (*) bowel wall thickening and hypoechogenicity of its wall; inflamed diverticulum (arrow). (B) Hypervascularisation of the walls of the inflamed colon and diverticulum in colour Doppler mode. (C) Increased echogenicity of the peridiverticular fat (*), corresponding to a peridiverticular phlegmonous area; diverticulum with thickened walls (arrow).

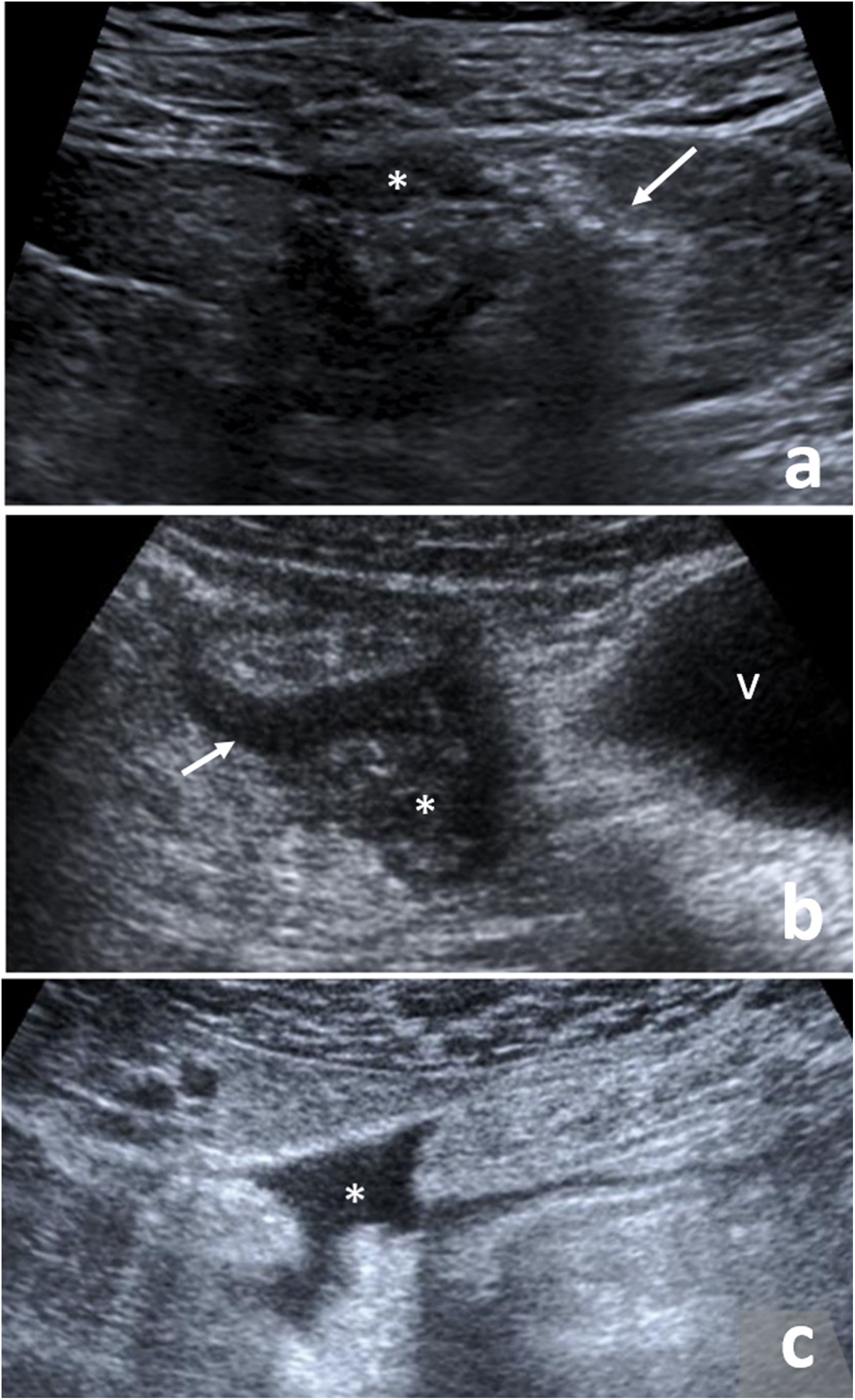

Ultrasound image of locally complicated acute diverticulitis of the left colon. (A) Thickening and hypoechogenicity of the wall of a diverticulum (*) and adjacent hyperechoic images without wall and with posterior acoustic shadow (arrow), corresponding to extraluminal gas (focal pneumoperitoneum). (B) Hypoechoic pseudonodular image (*) corresponding to an abscess of less than 4 cm in size adjacent to a segment of colon with a thickened wall (arrow); urinary bladder (v). (C) Locoregional free fluid (*).

Issues with classification. Regardless of the technique used for the initial diagnosis, when attempting to attribute the ADLC data to the chosen classifications, it was found that: a) the mild ADLC with bowel wall thickening and diverticula (n = 34) could not be classified either by the Hinchey or Modified Hinchey classifications; b) the Neff and modified Neff do not distinguish between the presence or absence of phlegmon; c) mild ADLC with added phlegmon (n = 70) was classified as Hinchey I, modified Hinchey Ia, Neff 0 and modified Neff 0; d) in locally complicated ADLC, the presence of localised fluid (n = 18) could not be classified as this finding was not considered (Table 3); e) localised pneumoperitoneum (n = 19) could only be classified using the modified Neff (Ia). f) locally complicated ADLC with abscesses less than 4 cm in size could not be classified by size using the Hinchey and modified Hinchey classifications and had to be classified as Hinchey I or II or modified Hinchey Ib or II solely on the basis of their location. This finding was classified as Neff I and modified Neff Ib; g) of the 19 patients with complicated ADLC, when a locoregional abscess of more than 4 cm in size was found (n = 7), it was defined as ADLC grade II in Neff and modified Neff, as grade I in Hinchey and as Ib in modified Hinchey for the same reason as with abscesses smaller than 4 cm; h) patients who had abscesses outside the pericolic space (n = 3) corresponded to grade III in Neff and modified Neff and grade II in Hinchey and modified Hinchey; and i) patients who had free abdominal fluid, whether or not associated with local or disseminated pneumoperitoneum (n = 9), were classified as Neff and modified Neff IV.

In 111 patients there was additional diagnostic confirmation of the existence of diverticulosis of the left colon, through surgery (6), colonoscopy (104) and barium enema (1).

DiscussionAlthough a presumptive diagnosis of ADLC can be made by combining clinical and analytical data, it must always be confirmed by imaging techniques.1,3 These techniques must also provide a rigorous classification of severity with prognostic value, in order to be of use for the choice of ideal ADLC treatment.

The utility of ultrasound in the diagnosis of ADLC has always been subject to debate30 and its use varies greatly from one area to another. However, the recommendation for ultrasound in this context is increasingly becoming established in the most recent clinical guidelines.11,31

This study confirms ultrasound to be a useful technique in the first step of the diagnostic assessment of mild and locally complicated ADLC. It also evaluates and detects deficiencies in the current classifications of acute diverticulitis in their assessment of the severity and prognosis of this disease.

The most common symptom was pain in the left iliac fossa or hypogastrium. Pain, leucocytosis and fever were the most commonly reported triad, although they are nonspecific findings which can appear in other disorders.32 Hackford et al. found that only 25% of cases had fever and 64% did not have leucocytosis.33 In our study, a small number of patients had fever, while 62% had leucocytosis. Although not all cases had leucocytosis, it was correlated with the severity of the ADLC by imaging. Therefore, as stated by other authors,34,35 leucocytosis would be a parameter to take into account as a prognostic factor. CRP was elevated in all of our patients, as also found by Laméris et al., who clinically diagnosed a quarter of their patients with suspected ADLC through the combination of left iliac fossa pain, absence of vomiting and elevated CRP.27 However, in contrast to the results published by other authors,36,37 the increase in CRP in our series was not proportional to the degree of severity of the diverticulitis. We also found no significant differences between severity and SIRS criteria, despite the most severe cases of ADLC tending to have more criteria.

Use of imaging techniques. Consistent with the action protocol used, ultrasound was indicated more as the first-line diagnostic technique in mild cases and CT in complicated ADLC. The main reasons for deviation from the protocol were not related to the severity of the ADLC, but to the lack of a radiologist in the time period when the patient was in the emergency department or the radiologist's inexperience in abdominal ultrasound.

Most patients with mild ADLC diagnosed by CT could have benefited from having ultrasound as the initial technique, without the need for additional CT, if there had been an experienced abdominal radiologist or on-call radiologist. When an ultrasound was performed as first option, a large proportion of locally complicated ADLC were correctly diagnosed and did not require further imaging tests. It could be inferred that a good number of the 29 patients with mild ADLC and the 32 with locally complicated ADLC who had CT first for non-clinical reasons might also have benefited from having an ultrasound. This deduction is based on four facts: 1) the rate of reassessment by CT of the cases initially diagnosed by ultrasound was low (14.2%); 2) the staging was only found to be more severe in three patients initially diagnosed as mild by ultrasound; 3) in four of the six patients with locally complicated ADLC in whom both techniques were performed, the findings were identical; and 4) only in three patients was the ultrasound technically difficult or inconclusive.

As this was a retrospective study, in the three patients diagnosed as mild by ultrasound and later as more severe by CT, it was not possible to determine whether this was due to an ultrasound with interpretation limitations or to a poor clinical course.

The high reliability of the ultrasound findings in mild and locally complicated ADLC in our series would support the use of ultrasound as the first-line diagnostic technique in ADLC, and this is consistent with the recommendations of other authors.30,38–40 It is also in line with both the step-up approach proposed by Andeweg et al11 and the latest clinical guidelines of the World Society of Emergency Surgery from 2020.31

In the specialised literature, no statistically significant differences have been shown in terms of the sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound and CT for the initial diagnosis of ADLC.9,32 It has not been possible to calculate the sensitivity and specificity of the two techniques due to the lack of a gold standard, but it has been shown that there are no statistically significant differences between the use of one or other technique in terms of length of hospital stay for mild and locally complicated ADLC.

Utility of the severity classifications. When our findings are compared with the published classifications, mild ADLC, in which only diverticula and bowel wall thickening are found, is only considered in two classifications, the Kaiser (grade 0) and the German consensus (grade Ia). When the patient also has associated phlegmon, the Hinchey and modified Hinchey classifications overestimate the ADLC, as do all the other classifications, except Neff and modified Neff (grade 0).

In locally complicated ADLC, localised pericolonic or pelvic fluid is not considered in any of the classifications described to date. However, we think it could be a surrogate marker of severity, as, in our study, detection of these factors was associated with a longer hospital stay and leucocytosis.

Localised pneumoperitoneum is only mentioned as a factor in the modified Neff classification and the German consensus, but the grades attributed are not consistent (Ia in the first and 2 a in the second).

In terms of abscesses, the Hinchey and modified Hinchey classifications do not consider their size, but rather their location, and compared to other classifications, they underestimate the severity of ADLC when the abscesses are in locations other than the pericolic region. Other classifications (Kaiser, Hansen/Stock and Siewert) also make no allowance for different sized abscesses. In our study, however, we found significant differences in the degree of severity depending on whether an abscess was larger than 4 cm and/or the presence of free fluid, where severity increased from locally complicated to complicated (Table 3).

The presence of abscesses outside the pericolic or pelvic space is classified as grade III in Neff and modified Neff, with this being more consistent with the way the disease progressed in our series. There is only one classification that is consistent with the Neff classification in this aspect (Kaiser), while the others either do not consider the location of abscesses or they underestimate its importance.

When free intra-abdominal fluid appears, whether or not associated with pneumoperitoneum, it is considered a grade IV ADLC in the Neff and modified Neff. The Hinchey and modified Hinchey classifications describe surgical findings (purulent peritonitis or faecal peritonitis). The presence of free pneumoperitoneum is considered grade IIc or III ADLC in the rest of the classifications.

Only the Buckley, Neff and modified Neff classifications differentiate between mild, moderate or locally complicated ADLC and severe complicated, although the grading is not consistent between them.

Limitations and strengths of the study. Among the limitations of the study are that it is a retrospective and single-centre study, carried out in an environment in which radiologists of the gastrointestinal system have extensive experience in and dedication to emergency abdominal ultrasound. However, only three of the radiologists who participated are actually gastroenterology specialists. We believe that one of the study's strengths is that it reflects the reality of care in a mid-level centre, in which the on-call radiologist is not physically present throughout the day, and may well belong to an area other than abdominal investigations. Another strength is that our series had a large number of cases and the results of the study can probably be extrapolated to other centres here in Spain providing a similar level of care.

Another limitation is that it was not possible to compare the ultrasound result (when used as a single imaging technique) with a reference CT to detect distant complications. It is therefore possible that some cases of locally complicated or complicated ADLC were underestimated as mild ADLC. However, in more than half of the patients, ultrasound was used as the only initial imaging test and only six had to be reassessed, of which only three ended up with a more severe classification. The possible underestimation of severity of patients diagnosed by ultrasound as mild ADLC did not affect their clinical outcome, as they progressed to cure with the treatment applied.

In conclusion, ultrasound is a useful technique in the diagnosis of mild and locally complicated ADLC and should be used as first-line technique, leaving CT for doubtful cases, inconclusive ultrasounds or clinically suspected complicated ADLC. The generic denomination of uncomplicated and complicated ADLC is insufficient to reflect patients' clinical outcomes. There are imaging findings in ADLC classed as complicated that show significant differences in length of hospital stay and leucocytosis levels.

The modified Neff classification is the one that best adapts to ultrasound and CT findings, although there are some findings not included that have been shown to have clinical significance. A consensus classification system should therefore be developed to include all imaging findings, establish prognostic factors and serve as a guide for therapeutic management.

Authorship- 1

Person responsible for the integrity of the study: NRG.

- 2

Study conception: NRG and JMB.

- 3

Study design: NRG and JMB.

- 4

Data collection: NRG and AND.

- 5

Data analysis and interpretation: NRG and JMB.

- 6

Statistical processing: NRG and JMB.

- 7

Literature search: NRG and AND.

- 8

Drafting of the article: NRG and JMB.

- 9

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually relevant contributions: MVGF, XPC, SPG and MLC.

- 10

Approval of the final version: NRG, ANG, MVGF, SPG, MLC, XPC and JMB.

This study received no specific grants from public agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank Dr Gemma Molist for her help and advice on statistics.