Groove pancreatitis is an uncommon type of chronic pancreatitis that affects the space between the head of the pancreas, the second portion of the duodenum, and the common bile duct. The main trigger is chronic alcohol abuse, which eventually leads to leakage of pancreatic juices into the pancreaticoduodenal groove, causing inflammation and fibrosis. The main differential diagnosis is with pancreatic adenocarcinoma, which is more common than groove pancreatitis.

Different imaging techniques make it possible to identify various findings (e.g., duodenal thickening or duodenal and paraduodenal cysts, which are characteristic of groove pancreatitis) that sometimes enable differentiation between groove pancreatitis and other entities, although there are no specific findings for each of them. Sometimes biopsy or surgery is required to establish the definitive diagnosis.

The treatment of groove pancreatitis is usually conservative, but in cases in which the symptoms do not improve, interventional procedures (biliary drainage) or surgery (Whipple technique) can be done.

La pancreatitis del surco es un tipo poco frecuente de pancreatitis crónica que afecta al espacio comprendido entre la cabeza del páncreas, la segunda porción duodenal y el colédoco. El consumo crónico de alcohol se ha descrito como el principal factor desencadenante, cuyo resultado final es la fuga de secreciones pancreáticas al surco pancreatoduodenal, con la consecuente afectación fibroinflamatoria en dicha localización. El principal diagnóstico diferencial de la pancreatitis del surco es el adenocarcinoma de páncreas, siendo este último más frecuente.

Gracias a la disponibilidad de las diferentes técnicas de imagen, es posible identificar varios hallazgos radiológicos que permiten distinguir, a veces, ambas entidades, como son el engrosamiento duodenal o la presencia de quistes duodenales y paraduodenales (característicos de la pancreatitis del surco), aunque no existen hallazgos específicos para cada una de ellas. En ocasiones es necesario recurrir a la toma de biopsia o cirugía para establecer un diagnóstico definitivo.

El tratamiento de la pancreatitis del surco suele ser conservador, pero en casos en los que no hay mejoría de los síntomas se realizan procedimientos intervencionistas (drenaje biliar) o cirugía (duodenopancreatectomía cefálica).

The pancreaticoduodenal groove (PDG) is a space that is bordered medially by the pancreatic head, laterally by the second and third portions of the duodenum and the major and minor papillae, with the inferior vena cava on its posterior aspect and the first portion of the duodenum on its superior aspect. This space contains part of the extrahepatic bile duct and the main pancreatic duct (MPD), lymph nodes, and vascular structures such as the gastroduodenal artery.1–3

In 1973, Becker and Bauchspeinchel introduced the concept of paraduodenal pancreatitis to refer to a rare and localised form of chronic pancreatitis that affects the PDG space.1,4 Later, in 1982, Stoller et al. coined the term currently used to describe this entity as groove pancreatitis (GP),5 although it is also known as paraduodenal pancreatitis, cystic dystrophy of heterotopic pancreas, myoadenomatosis, periampullary duodenal wall cyst or pancreatic hamartoma of the duodenum.4 In 2004, Adsay and Zamboni grouped all these nomenclatures under the universal term groove pancreatitis.6 Finally, in 1991, Becker and Mischke differentiated between the pure form of GP, when it only affects the PDG space itself, and the more common segmental form, where the involvement extends to the pancreatic head.2,5,7

Due to the complex anatomy of the PDG space and the relationship between the structures it is comprised of, differentiation between benign and malignant entities is challenging.8 Therefore, it is important to understand GP and be able to differentiate it from other entities that affect the pancreatic head, the most relevant being adenocarcinoma.5

GP is an unusual form of chronic pancreatitis that occurs secondary to the formation of fibroinflammatory tissue in the fat of the PDG,5 without necessarily involving the rest of the pancreas. This makes diagnosis difficult.9 The identification of this entity poses a significant challenge, which is why a biopsy is usually required in order to establish diagnostic certainty.7

AetiopathogenesisThe underlying cause of this pathology is not well understood, although multiple theories and contributing factors have been proposed. Prolonged alcohol consumption appears to be the strongest predisposing and triggering factor.2,6

GP could be triggered by obstruction of the minor papilla or the accessory pancreatic duct of Santorini due to increased viscosity of pancreatic secretions conditioned by tobacco and alcohol or by hyperplasia of the Brunner glands in the duodenal mucosa.4,6,7 Another of the proposed mechanisms is a change in pancreatic secretion in the minor papilla secondary to chronic alcohol consumption or the presence of heterotopic pancreas causing an increase in pressure in the duct of Santorini with the consequent formation of pseudocysts and leakage of pancreatic secretions into the PDG.2,10 An association with peptic ulcer has been described, although unlike that which occurs with other types of pancreatitis, an association with autoimmune diseases or the presence of cholelithiasis has not.7 In addition, the specific location of this entity in the PDG around the minor papilla suggests that apart from functional abnormalities (secondary to alcohol and tobacco), predisposing factors exist in the form of anatomical abnormalities such as pancreas divisumor absence/stenosis of the duct of Santorini.1,2

The final and common result of these possible causes of GP is the extravasation or leakage of activated pancreatic proteolytic enzymes into the PDG, which leads to a chronic inflammatory cascade and fibrosis.11

Signs and symptomsGP usually affects men in their fourth or fifth decade of life with a history of alcoholism and smoking and in up to 50% of cases, a history of prior acute pancreatitis. Clinically, it can present as an acute episode of pancreatitis with postprandial abdominal pain and recurrent nausea or vomiting, but it can also follow a chronic and insidious course of months of evolution with abdominal pain, weight loss and jaundice that may look more like a neoplastic process than pancreatitis.2,4–7,10 There are exceptional cases in which GP can present as gastric obstruction and sometimes cause serious complications such as perforation or gastrointestinal bleeding.2,10

In laboratory studies, pancreatic enzymes and tumour markers are not usually elevated (unlike with pancreatic adenocarcinoma [PAC] where CA 19−9 is elevated), and alkaline phosphatase can be elevated without common bile duct obstruction.7

DiagnosisDiagnosis of GP is based on clinical suspicion and different diagnostic tests, as it is difficult to obtain a definitive diagnosis with imaging studies alone because the findings are non-specific and overlap with other entities such as PAC.5 It is important to be aware that GP is much less common than PAC. Some studies describe incidences of less than 2% in pancreatic resections in patients with chronic pancreatitis.11

In cases of pure GP, differential diagnosis should be established with cholangiocarcinoma and acute pancreatitis and in the case of the segmental form of GP, with PAC.5

According to Gabata et al., imaging studies are not sufficient to differentiate GP from PAC, especially in cases where there are no typical GP findings, such as cysts in the duodenal wall or inside the fibroinflammatory mass, so it is sometimes necessary to take biopsies.5 For many authors, endoscopic ultrasound is a test indicated for diagnosis because it not only allows visualisation of the involvement of the structures of the PDG space, such as duodenal or MPD stenosis, but it also allows samples to be obtained for pathological study. Surgery may sometimes be necessary to establish a definitive diagnosis.4,5 Regarding the imaging tests of choice, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the imaging modalities used for the diagnosis of GP since they can locate the PDG and fibroinflammatory changes very well.11

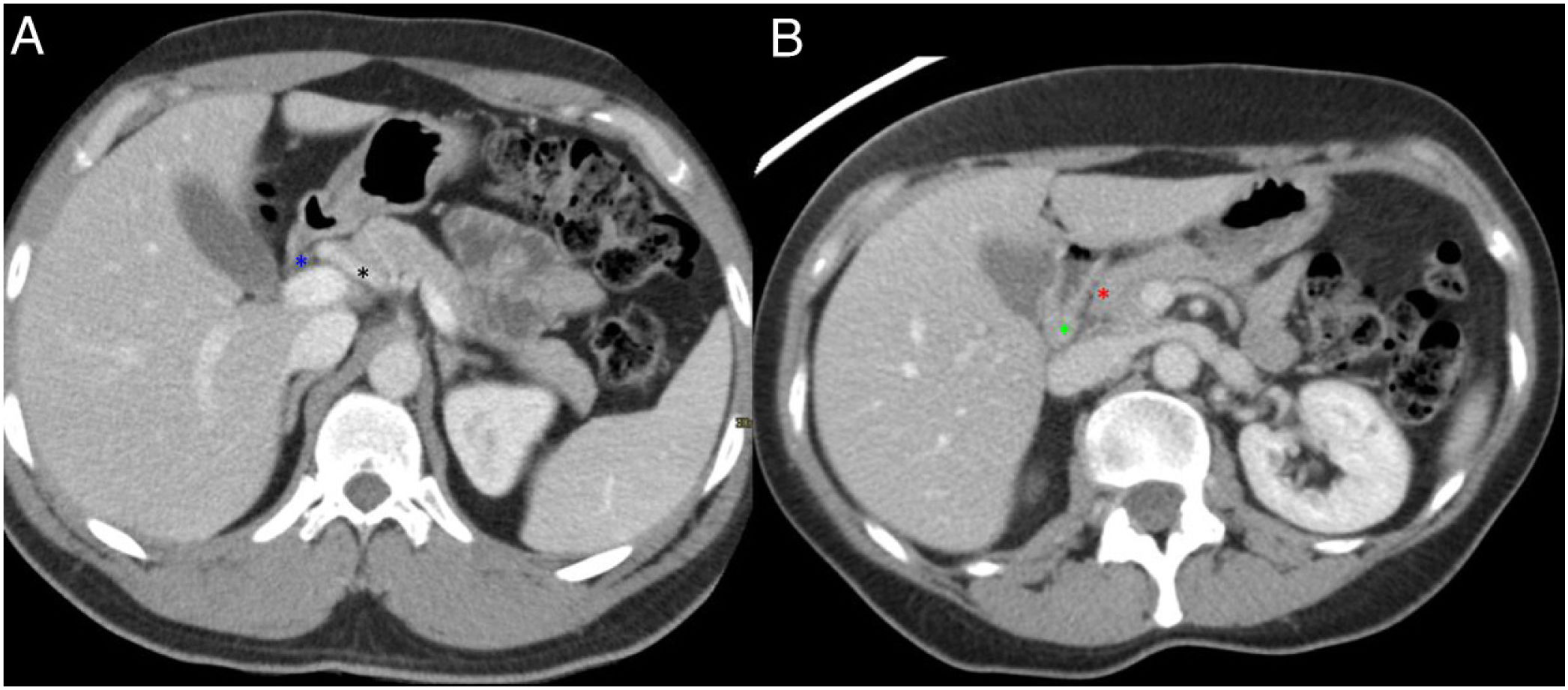

Radiological findingsSince most of the time patients present with symptoms of acute pancreatitis, the initial test is usually a CT scan. Both CT and MRI make possible very good anatomical definition and delimit the inflammatory involvement in GP cases very well (Fig. 1). In addition, since pancreatic lesions are hypovascular, if a biphasic study is performed that includes an arterial phase with contrast, this provides more information than a study with a single portal phase, as in this way, it is possible to identify, in addition to the inflammatory changes, possible lesions in the pancreatic parenchyma that will be visualised as areas with decreased uptake. The differential diagnosis of these will include neoplastic lesions or areas of necrosis in the context of pancreatitis.

Normal anatomy of the pancreaticoduodenal groove (PDG). Axial slices of the abdomen after administration of intravenous contrast in the portal phase (A and B). PDG: space between the common bile duct (blue asterisk, A), the common hepatic artery (black asterisk, A), the pancreatic head (red asterisk, B), and the second portion of the duodenum (green asterisk, B).

However, MRI offers a better anatomical definition and contrast resolution and allows for better differentiation of cystic lesions from solid ones. MRI is also superior to CT for evaluating the bile duct (Fig. 2).1,4

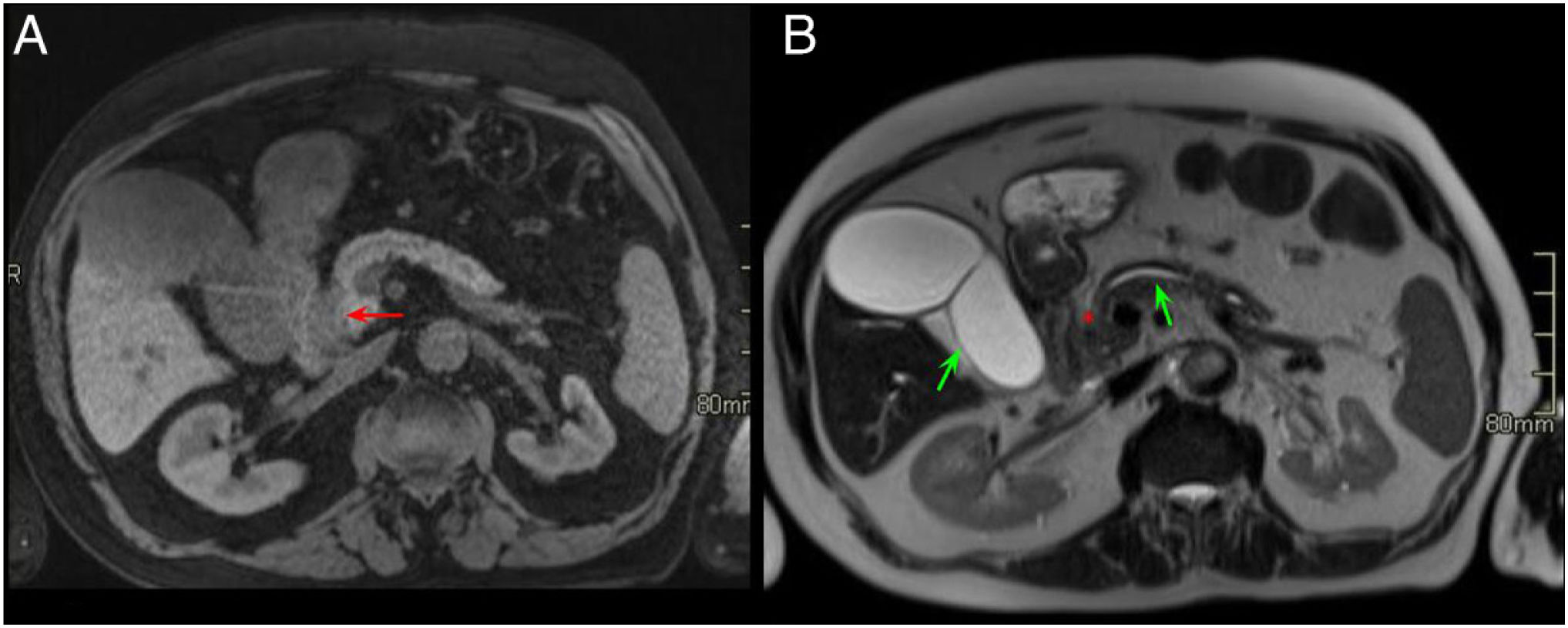

Normal anatomy of the pancreaticoduodenal groove (PDG). Axial slices of the abdomen in fat saturation T1 (A) and T2 (B). PDG: space between the pancreatic head (red asterisk, A and B), the second portion of the duodenum (green asterisk, A) and the common bile duct (blue arrow, A and B).

For an optimal study of the pancreas and the PDG space with CT, it is recommended that the patient fast for at least three hours and drink up to a litre of a low-density contrast agent, such as water, prior to the study.8 Next, a triphasic study is performed: without contrast, in the arterial phase and the portal phase.3,8,9

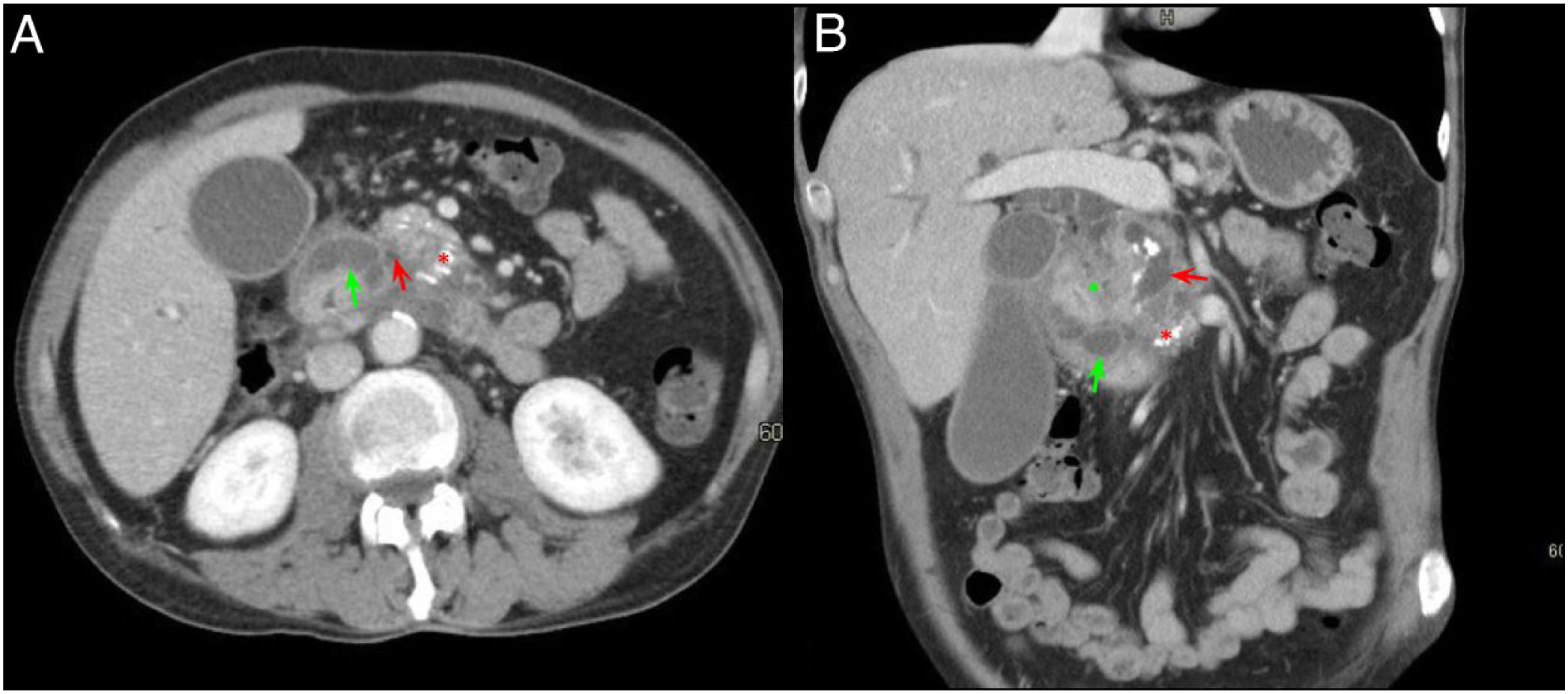

The pure form of GP usually presents on CT as trabeculation of fat that occupies the space between the pancreatic head and the second portion of the duodenum, with adjacent inflammatory changes, even progressing and forming a hypodense mass of soft tissues within the groove cavity that presents a curvilinear, lamellar or crescent shape, a finding better visualised in the coronal projection (Fig. 3).2,5,7,11

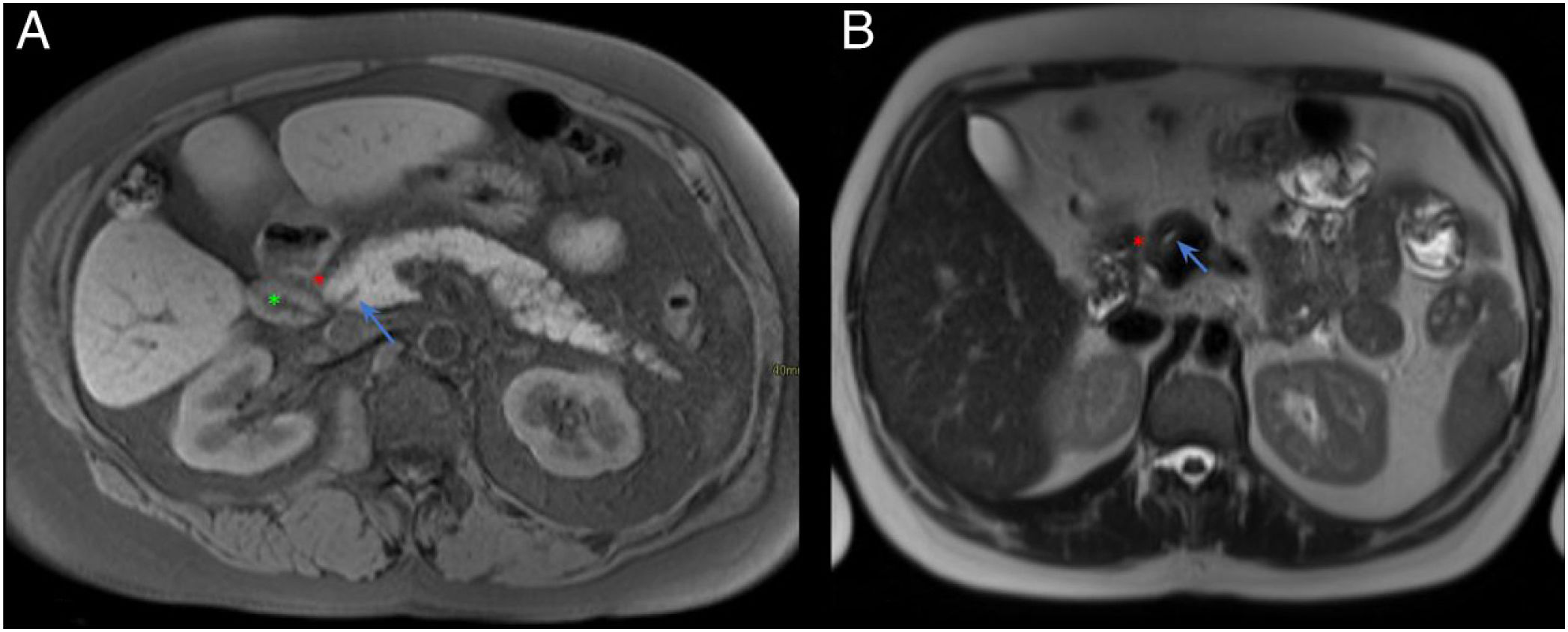

A 54-year-old patient admitted for an episode of acute pancreatitis. Axial slices of the abdomen with intravenous contrast in the portal phase. A) Enlargement of the pancreatic head with effacement of the pancreaticoduodenal groove (red asterisk). B) Ectasia of the main pancreatic duct and distal common bile duct (green arrow) with filling defect in the portal vein in relation to portal vein thrombosis (black arrow). Findings probably related to groove pancreatitis.

In cases of GP in its segmental form (not exclusive to the groove, but rather extending to the pancreatic head), the involvement is evidenced as a hypodense mass in the pancreatic head that can be associated in some cases with MPD dilatation and a certain degree of common bile duct stenosis with retrograde intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct dilatation.1,2,7 In cases in which MPD stenosis occurs, it is usually progressive and regular, unlike in PAC cases, unlike when stenosis occurs it is usually abrupt and irregular.7 This inflammatory mass in the PDG shows late and progressive enhancement after contrast administration, due to chronic inflammation and the fibrotic component.7,10,11 In addition, it is common for the duodenum to show some mural thickening on its medial aspect and cystic formations on the duodenal wall or even in the PDG itself (Fig. 4).3,7,10

A 60-year-old male with constitutional syndrome. Axial slice (A) and coronal slice (B) of the abdomen with intravenous contrast in the portal phase. Dilatation of the main pancreatic duct (red arrow, A and B) and presence of calcifications in the pancreatic head-body (red asterisk, A and B), in relation to chronic pancreatitis. Occupation of the pancreaticoduodenal groove (green asterisk, B) and duodenal wall thickening with cystic lesions inside (green arrow, A and B). Findings consistent with groove pancreatitis.

As GP is a type of chronic pancreatitis, the pancreas usually presents with the typical chronic changes: atrophy with fatty replacement, calcifications or calculi inside the MPD (Fig. 4).4,7,10

In addition, regardless of the subtype of GP that exists, this entity is not usually associated with free fluid or inflammatory involvement of the retroperitoneum.7 The presence of infiltration of vascular structures or adenopathies, a more frequent finding in PAC cases, is not common either, but rather the peripancreatic vessels, specifically the gastroduodenal artery, are displaced.1,9

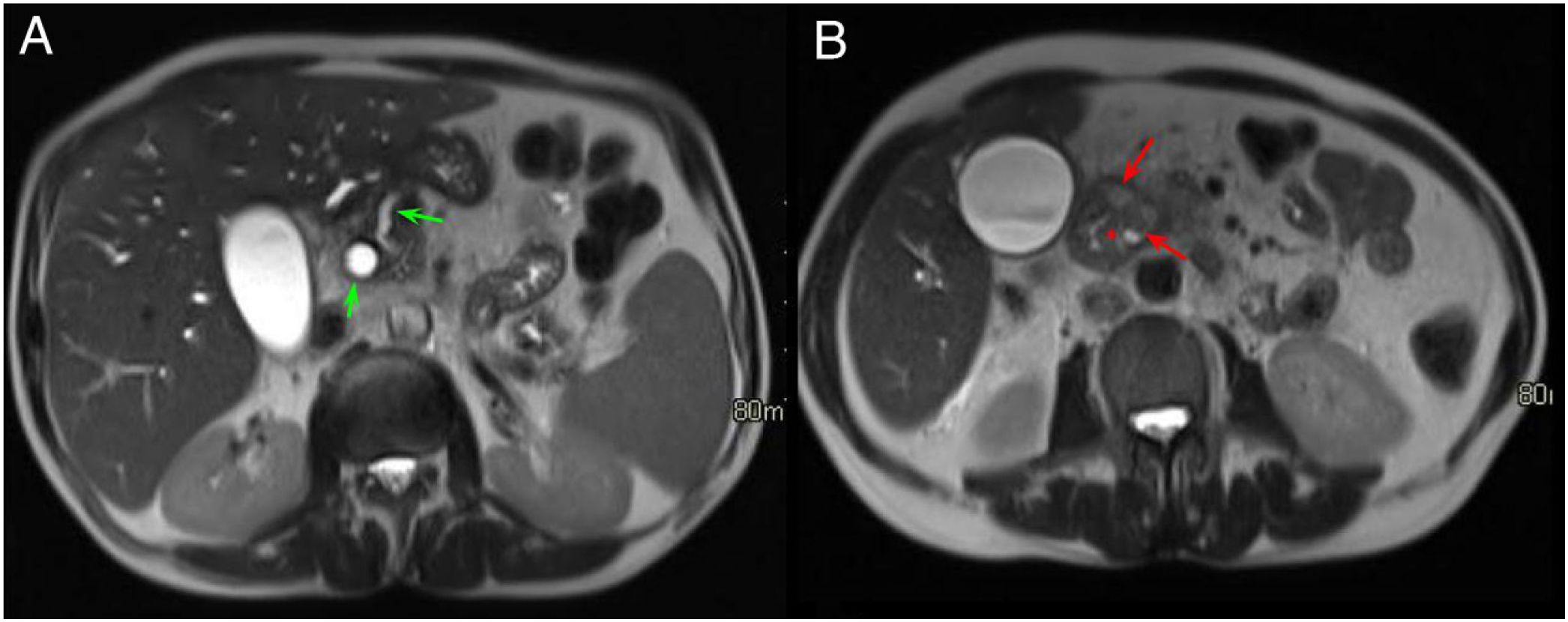

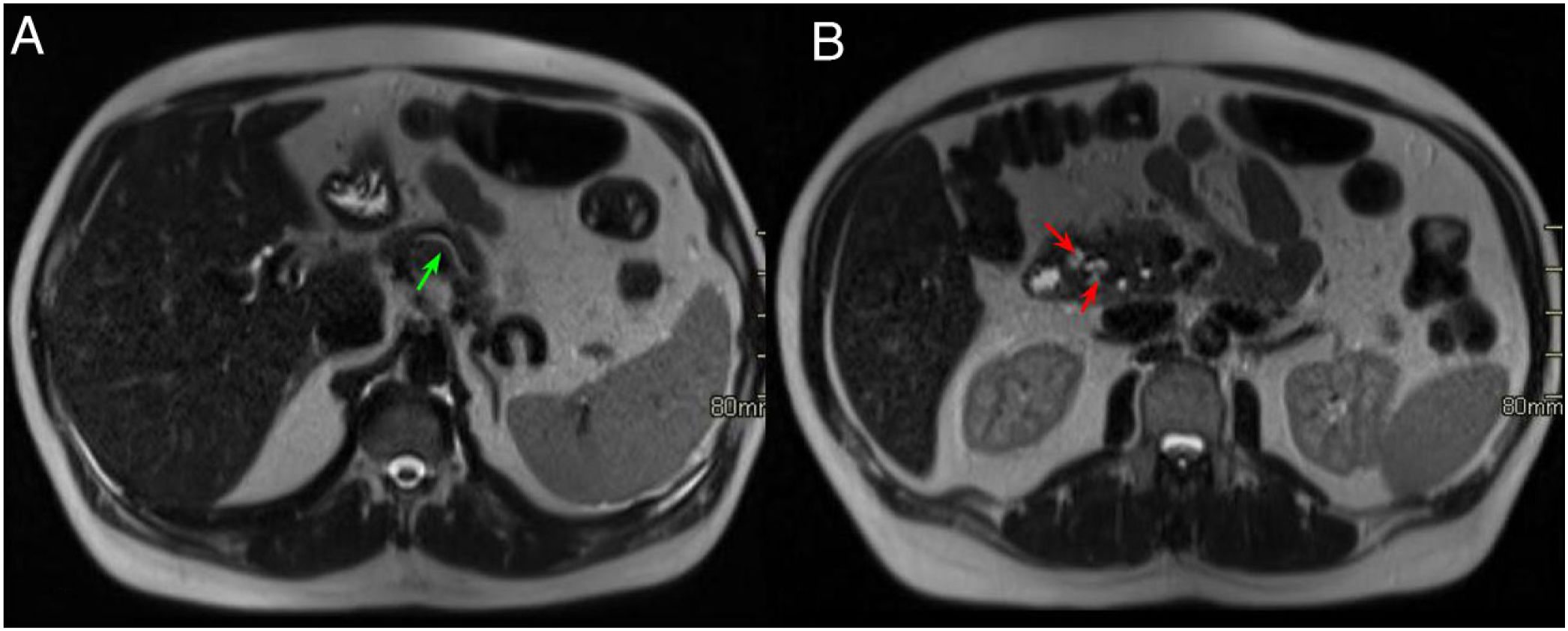

On MRI, lamellar inflammatory involvement in the PDG is identified as a hypointense signal on T1-weighted sequences, with heterogeneous signal intensity on T2-weighted and STIR sequences (Figs. 5 and 6). This inflammatory picture exhibits patchy and progressive enhancement after the contrast administration due to its fibrotic content.7,9 In acute phases, the inflammatory involvement in the PDG usually exhibits a higher signal intensity in the T2-weighted sequence due to the presence of oedema and fluid that progressively transforms into fibrotic tissue in the subacute/chronic phase and in T1- and T2-weighted sequences it exhibits a lower signal intensity due to parenchymal atrophy and fibrosis. Therefore, T2-weighted sequencing is very useful for inferring the degree of activity.7

Same case as in the previous figure. Axial slices of the abdomen in T2-weighted sequences. A) Dilatation of the intra- and extrahepatic bile duct and the main pancreatic duct in the body and tail of the pancreas, with tapering of the main pancreatic duct in the pancreatic head (green arrows). B) Hyperintense lesions in the medial wall of the duodenum corresponding to cystic lesions (red arrows) with effacement of the pancreaticoduodenal groove (red asterisk).

A 48-year-old man with a history of alcoholism and recurrent acute pancreatitis. Axial slices of the abdomen in T2-weighted sequences. A) Dilation of the main pancreatic duct (green arrow). B) Effacement of the fat planes of the pancreaticoduodenal groove and small images with a cystic appearance in the duodenal wall (red arrows). These findings, given the patient's history, are compatible with groove pancreatitis.

In both subtypes of GP, the medial aspect of the duodenum is thickened with multiple cysts inside its wall and in the groove, which are identified as hyperintense foci on T2-weighted sequences (Figs. 5 and 6).7 Some authors argue that these intramural cysts of the duodenum are heterotopic pancreatic islets or even dilated ductal branches of the duct of Santorini.1

Cholangiographic sequences are used to show whether there is an involvement of the biliary and pancreatic ducts, which are identified as areas of gradual stenosis with smooth borders. In cases of MPD stenosis, it will be located close to the ampulla of Vater.7,9

Other findings associated with GP include widening of the space between the ampulla and the duodenal lumen as a result of fibrotic infiltration of the PDG and the duodenal wall, and stenosis of the ampulla and the common hepatic duct, which will dilate in a "banana shape,'' and which could also lead to gallbladder distention.7

On ultrasound, GP is identified in early stages as a hypoechoic band in the PDG that corresponds to inflammatory infiltration and heterogeneous echogenicity of the pancreatic head, and, on some occasions, ultrasound allows for visualisation of small cysts in the groove.12 Duodenal thickening is evident in late stages.2,12

Therefore, when faced with the findings of inflammatory involvement in the PDG (pure form) or with extension to the pancreatic head (segmental form), dilation of the MPD and the extrahepatic bile duct, duodenal thickening and cystic formations in the duodenum or in the PDG itself, GP should be considered as the first possibility.

TreatmentGP treatment is usually conservative, with support measures that combine fasting, enteral (or parenteral in cases of duodenal stenosis) nutrition, somatostatin, and abstinence from alcohol and smoking.2,7,10

Sometimes surgical intervention is required due to obstruction of the bile duct or gastric emptying being impossible.

In chronic cases of patients with severe or clinical pancreatic insufficiency that does not respond to conservative treatment, minimally invasive treatments such as endoscopic biliary drainage (which can also serve as a bridge to definitive surgery) or definitive surgical treatment can be opted for; in this case, cephalic pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple surgery).7,13

Differential diagnosisThe main differential diagnosis that must be taken into account with GP, specifically regarding the segmental form, is PAC, although it should be noted that GP is much less common than PAC.2,4 Other differential diagnoses to take into account in cases of pure GP, although less common, are neoplasms that originate in structures close to the PDG, such as primary duodenal neoplasm, cholangiocarcinoma of the distal common bile duct, ampulloma or autoimmune pancreatitis.1,2,9 Ampullomas, in particular, are difficult to differentiate from GP when they are large masses. However, they present as well-defined masses in the papilla region, whereas GP usually presents as a less well-defined crescent-shaped soft tissue mass.1

PAC is an entity that develops more frequently in men in their sixth decade of life and usually presents with progressive and insidious symptoms of abdominal pain and jaundice and with elevated tumour markers.4

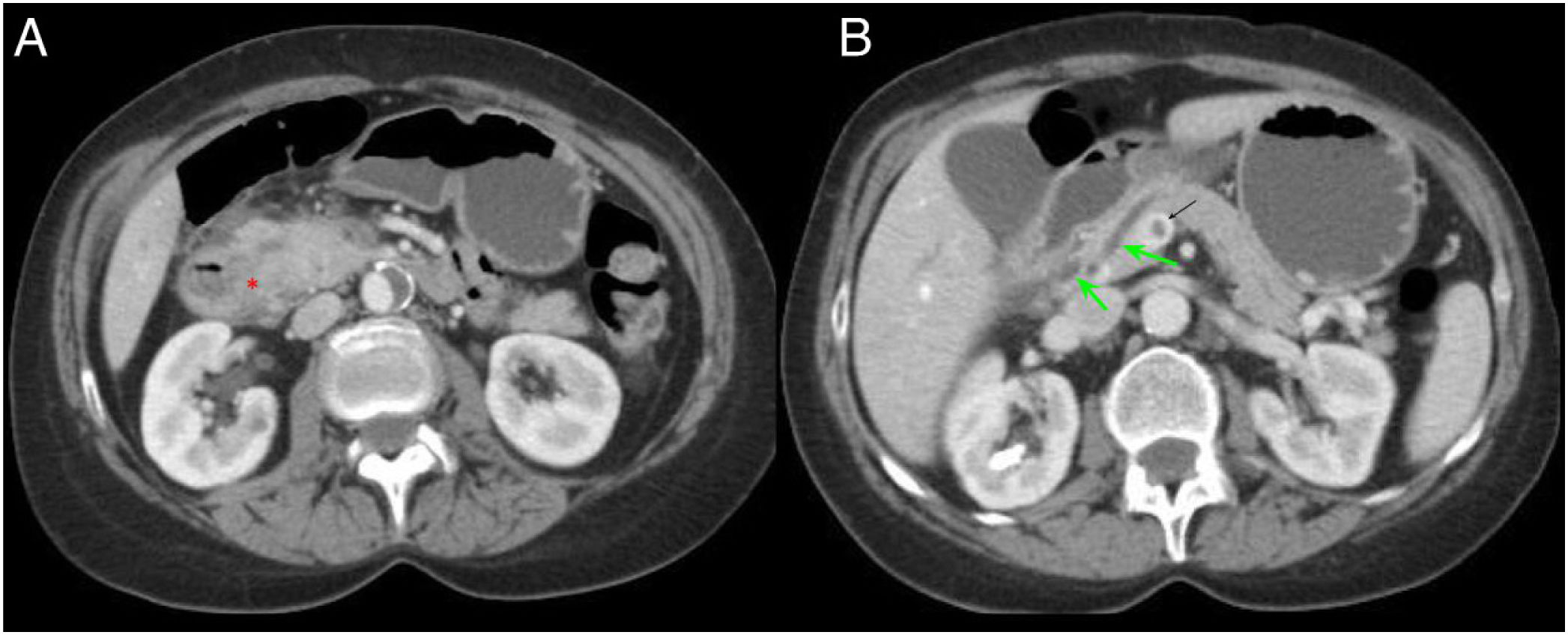

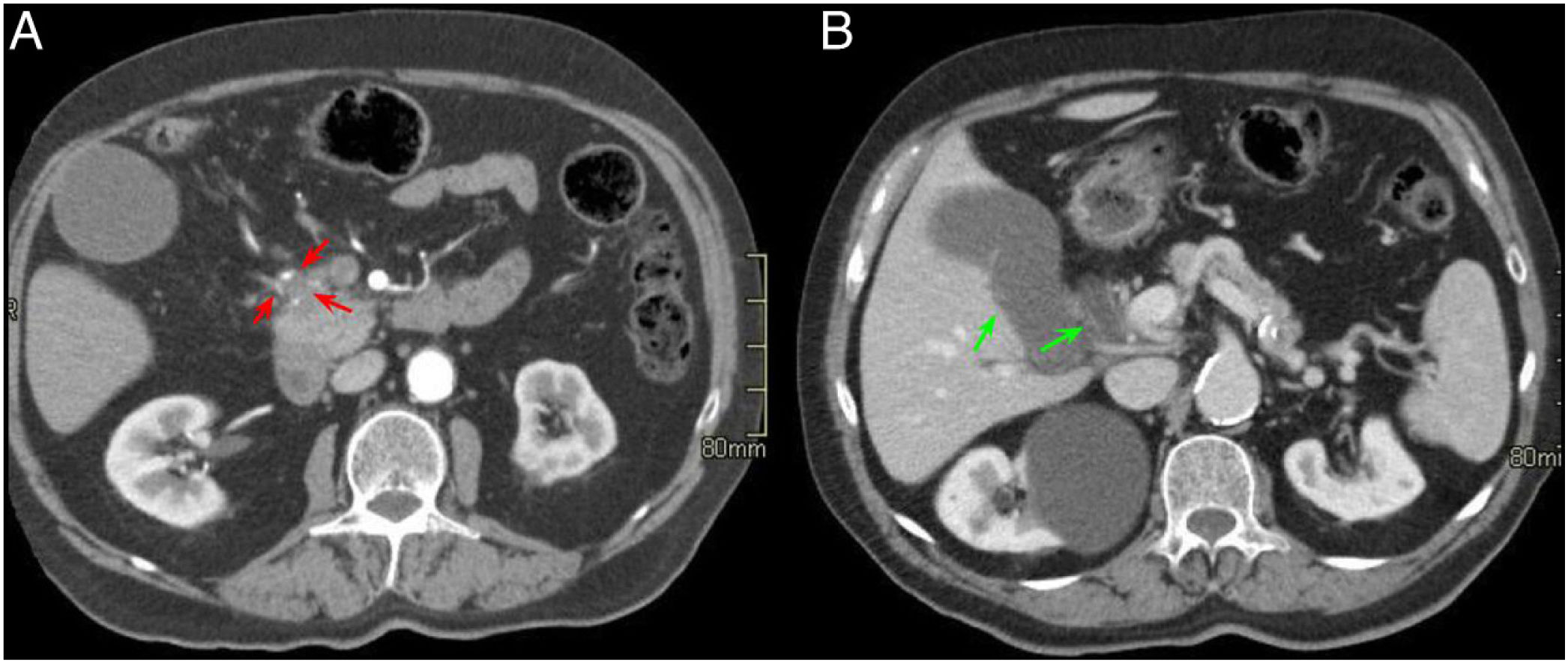

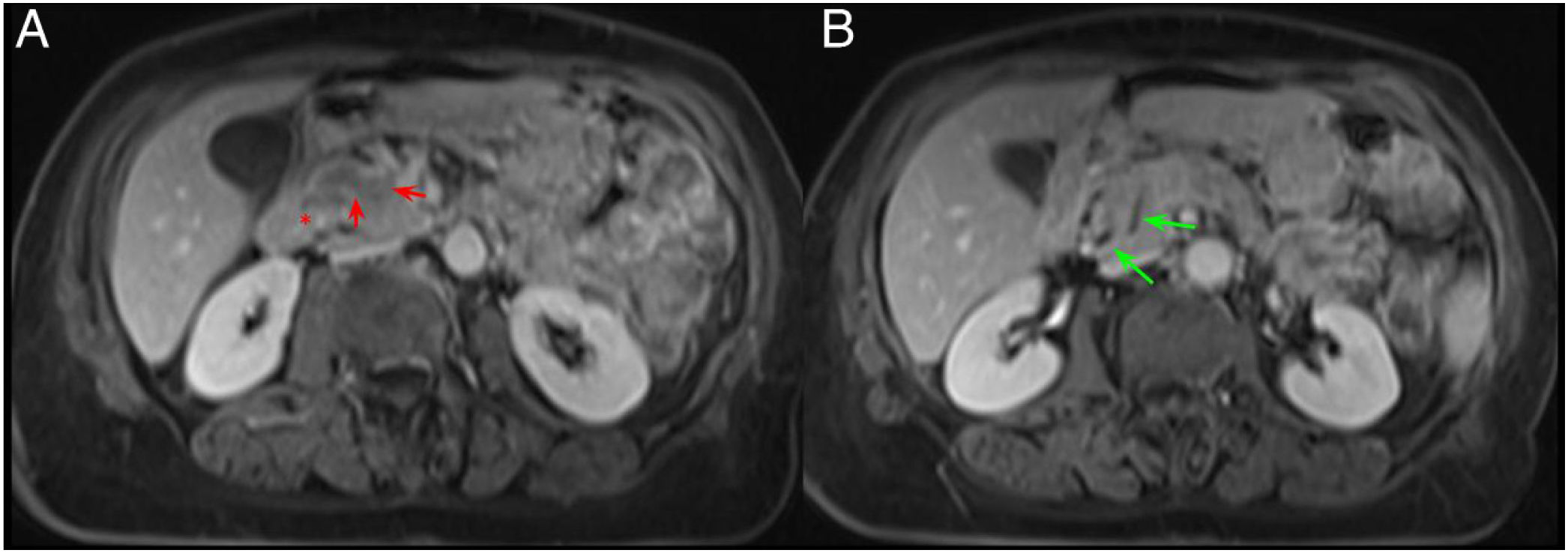

Duodenal wall thickening with secondary luminal stenosis and cysts in its wall or the groove are uncommon findings in PAC, which, if present, would incline us towards a diagnosis of GP. However, the existence of a hypointense mass on T1 with vascular invasion, adenopathies or infiltration of the retroperitoneum would make a diagnosis of PAC more feasible (Figs. 7 and 8).7,9,10 Another finding that differentiates PAC from GP is the dilation of both the MPD and the common bile duct (double duct sign) (Figs. 9 and 10).8 The pattern of enhancement of these two entities in post-contrast studies is also different and helps to differentiate them. PAC shows poor, homogeneous enhancement, while GP usually shows late, heterogeneous enhancement.7

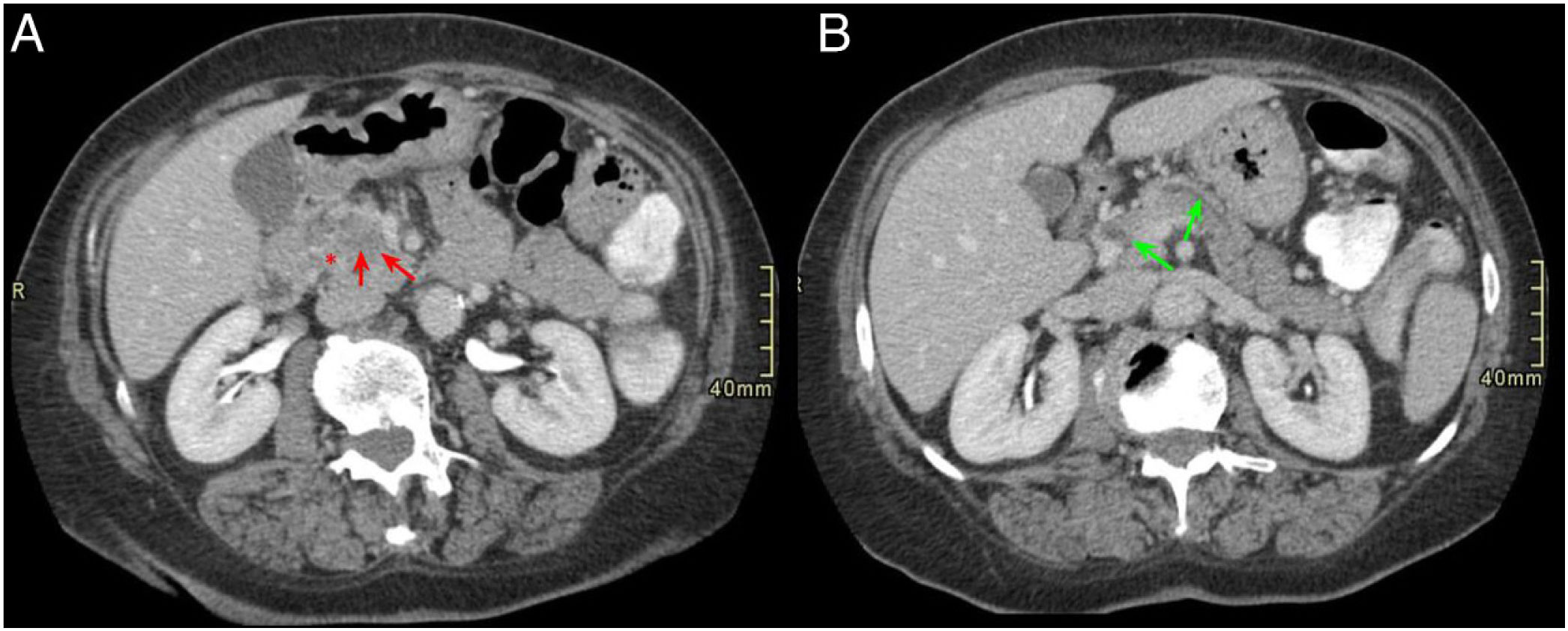

A 74-year-old male with jaundice and constitutional syndrome. Axial slices of the abdomen with intravenous contrast in the arterial phase (A) and portal phase (B). Small hypovascular mass in the pancreatic head-uncinate process (red arrows, A) that surrounds the gastroduodenal artery and causes dilatation of the extrahepatic bile duct and gallbladder hydrops (green arrows, B).

Same case as in the previous figure. Axial slices of the abdomen in T1-weighted sequence with fat saturation (A) and HASTE sequences (B). A hypointense mass (red arrow, A) previously identified on computed tomography with infiltration of the pancreaticoduodenal groove (PDG) (red asterisk, B) is observed in the anterior and medial aspect of the pancreas and in contact with the second duodenal portion. In the HASTE sequence, gallbladder hydrops, pancreatic duct dilation (green arrow in B) and occupation of the PDG are observed. The final diagnosis was pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

A 65-year-old woman with chronic diarrhoea. Axial slices of the abdomen after administration of intravenous contrast in the portal phase (A and B). Slight hypodensity in the pancreatic head-uncinate process in contact with the superior mesenteric vein (red arrows, A). Dilatation of the extrahepatic bile duct and the pancreatic duct (double duct sign) (green arrows, B) and effacement of the pancreaticoduodenal groove (red asterisk, A). Findings suggestive of pancreatic neoplasm.

The same patient as in Fig. 9. Axial slices of the abdomen in post-contrast fat saturation T1-weighted sequence (VIBE). A and B) Hypointense mass in the pancreatic head compared to the rest of the pancreas with the occupation of the pancreaticoduodenal groove (red arrow and asterisk, A) and dilatation of the extrahepatic bile duct and the pancreatic duct (green arrows, B). The final diagnosis was pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

There are other radiological findings described that do not help to differentiate GP from PAC, such as dilation of the MPD or the common bile duct, since, due to anatomical location, both can be affected in both entities,2,3 although in cases of GP the stenosis of the common bile duct is usually regular and smooth and in cases of PAC it is usually irregular and abrupt.2

On many occasions, a definitive diagnosis requires pathological confirmation.7

For the group led by Kalb et al. there are three findings that present a diagnostic accuracy of 87.2% for the diagnosis of groove pancreatitis, with a negative predictive value for adenocarcinoma of 92.2%. These findings are: mural thickening of the medial aspect of the duodenum, the presence of cysts both in the duodenal wall and in the groove, and demonstration of late enhancement of the second portion of the duodenum.14

In their retrospective study of 53 patients, Beker et al. described three signs in cholangiographic sequences to differentiate a PAC from a pancreatic head pseudomass, different entities with different treatments.15 The "corona" sign is identified in cases of PAC when the secondary branches of the MPD are only dilated in the periphery of the mass, since it displaces them. In fibroinflammatory entities, dilated secondary branches are found within the inflammatory mass.15 The "duct-interrupted" sign is described in patients with PAC in which the duct within the neoplastic mass is completely interrupted by it with proximal dilatation of the MPD. Situations in which the MPD is dilated throughout the mass and the pancreas or with stenosis with/without retrograde dilatation, are not considered typical findings of PAC.15 Finally, they describe the “attraction” sign, typical of pancreatic pseudomass, since fibroinflammatory processes tend to cause retraction of adjacent structures, not invasion of them. Therefore, this sign is described in inflammatory cases in which there is an attraction of the common bile duct towards the inflammatory mass with stenosis and proximal dilatation.15

ConclusionsGP is an uncommon subtype of chronic pancreatitis that is subdivided into a pure form (only affects the PDG) and a segmental form (extends to the pancreatic head). Its main differential diagnosis is with PAC, it being possible, on occasion, to distinguish them with the use of different imaging techniques and the combination of the different radiological findings.

Authorship- 1.

Responsible for study integrity: ABS, ICS.

- 2.

Study concept: ABS.

- 3.

Study design: ABS, ICS.

- 4.

Data acquisition (clinical cases): ABS.

- 5.

Data analysis and interpretation: ABS, ICS.

- 6.

Statistical processing: N/A.

- 7.

Literature search: ABS, ICS.

- 8.

Drafting of the article: ABS, ICS.

- 9.

Critical review of the manuscript with intellectually significant contributions: ABS, ICS.

- 10.

Approval of the final version: ABS, ICS.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

We would like to thank Dr José Luis Fernández Cueto, specialist physician of the Gastroenterology Department of the Hospital Universitario de Getafe [Getafe University Hospital], for his collaboration with and participation in the search for clinical cases and critical review of the manuscript.