The identification of biomarkers of disease progression continues to be a necessity in the approach to multiple sclerosis (MS), a disabling neurological disease more common in young adults, which can have different phenotypes, among which relapsing-remitting (RRMS), primary progressive (PPMS) and secondary progressive (SPMS). Among biomarkers, the determination of neurofilament light chain (NfL) levels in both cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum have been shown to predict the severity of MS. Therefore, the objective of the present work was to evaluate the levels of NfL in patients in different stages of MS.

MethodologyA descriptive study was carried out, which included 70 patients diagnosed with MS; plasma NfL levels were analyzed using the adsorption enzyme immunoassay kit and the levels of the MS patients were compared with the levels of control patients.

ResultsIn patients with MS, 87,14% were women, 21,43% were taking antidepressant drugs, 48,57% had vision complications.and 80% had spinal injuries. It was found that patients with RRMS phenotype and of male sex have higher levels of NfL.

ConclusionsThe results show an increase in NfL in RRMS and in male patients, which suggests that there may be greater neuroaxonal deterioration in men and that they have this disease phenotype. However, future studies aimed at optimizing, standardizing, and implementing new technologies are necessary to address the predictive value of these biomarkers that can contribute to the management of the disease.

La identificación de biomarcadores de progresión de la enfermedad continúa siendo una necesidad en el abordaje de la esclerosis múltiple (EM), una enfermedad neurológica discapacitante más frecuente en adultos jóvenes, la cual puede tener diferentes fenotipos entre los cuales se destacan el remitente recurrente (EMRR), primaria progresiva (EMPP) y secundaria progresiva (EMSP). Entre los biomarcadores, la determinación tanto en líquido cefalorraquídeo (LCR) como en suero de niveles de los neurofilamentos de cadena ligera (NfL) han mostrado predecir la severidad de la EM. Por lo tanto, el objetivo del presente trabajo fue evaluar los niveles de NfL en pacientes en diferentes estadios de la EM.

MetodologíaSe realizó un estudio descriptivo, que incluyó 70 pacientes con diagnóstico de EM; se analizaron los niveles plasmáticos de NfL utilizando el kit de enzimoinmunoanálisis de adsorción y los niveles de los pacientes con EM fueron comparados con los niveles de pacientes controles.

ResultadoEn los pacientes con EM el 87,14% fueron mujeres, el 21,43% tomaban fármacos antidepresivos, el 48,57% tenían complicaciones de visión y el 80% tenían lesiones en medula. Se encontró que, pacientes con fenotipo EMRR y de sexo masculino presentan mayores niveles de NfL.

ConclusionesLos resultados muestran un incremento de los NfL en EMRR y en pacientes de sexo masculino, lo cual sugiere que puede existir un mayor deterioro neuroaxonal en hombres y que tengan este fenotipo de la enfermedad. Sin embargo, se hace necesario futuros estudios dirigidos a la optimización, estandarización e implementación de nuevas tecnologías para abordar el valor predictivo de estos biomarcadores que puedan aportar al manejo de la enfermedad.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common disabling neurological disease in young adults.1 Its development involves inflammatory, demyelinating, neurodegenerative and glial response processes, which are responsible for the heterogeneity and individual variability in the expression of the disease, its prognosis and its response to treatment.2 Currently, there are 4 known forms of clinical presentation, called clinically isolated syndrome; relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS); secondary progressive MS (SPMS), and primary progressive MS (PPMS).3 Knowledge of the biological factors involved in the onset, reactivation and progression of the disease facilitates the study of biomarkers for timely diagnosis and adequate therapeutic follow-up in patients suffering from MS. Some biomarkers reflect tissue damage and are released into the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and peripheral blood, showing patterns that, in addition to being associated with the diagnosis, are fundamental tools in the prognosis and response to treatment at different stages of the disease, together with clinical and neuroimaging parameters, are able to establish predictive patterns of MS progression.4 In MS, axonal damage, which is present from the early stages of the disease, is considered the main mechanism causing irreversible neurological disability.5 In this context of axonal injury, it has been found that extracellular secretion of neuronal cytoskeletal proteins occurs. Neurofilaments (Nfs) in the heavy (180−200 kDa), medium (145−150 kDa) and light (NfL) (68−70 kDa) chains may be found. NfL chains reach the CSF and the bloodstream, where they can be detected in serum or plasma. Accordingly, Nfs have become important when monitoring patients and can be correlated with the clinical evolution and prognosis of patients with the disease.6,7 NfLs may have a prognostic value for the conversion of a clinically isolated syndrome to definitive MS. NfLs have been related to acute inflammatory processes. For example, levels are higher in patients in relapse compared to patients in remission.7

Before NFs can be recommended as markers in clinical use, certain considerations must be made. The variations in assay characteristics such as sensitivity and stability between laboratories, between different centres, and in various cohorts need to be tested. The stability of these proteins justifies the application of standardised storage procedures for both CSF and serum. The next important step would be the use of these biomarkers in randomised clinical trials to assess their clinical predictive value for disease progression and responses to MS treatment. Until then, the assessment of serum Nfs should be considered a focus of biomarker research in MS. The aim of this study was therefore to assess NfL levels in patients at different stages of MS in a specialised centre in the city of Medellin.

Materials and methodsA descriptive, cross-sectional study was conducted which included patients diagnosed with MS (diagnostic code G35X) who consulted the Neurological Institute of Colombia, which is a reference centre for disease control where care is provided from outpatient consultation to intensive care unit located in the city of Medellín.

ParticipantsSeventy patients met the study criteria: (1) confirmed diagnosis of MS according to McDonald's criteria; (2) attendance at neurology check-ups in outpatient consultation at least once during the study period, and (3) with evaluation of the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) at the last consultation. Patients who did not have a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) record were excluded. For the control group, people who did not have a diagnosis of MS or any type of diagnosed disease of the central nervous system were invited to participate.

The EDSS is an instrument used to evaluate disability in people with the disease; The EDSS assigns a score based on the impairment of various neurological functions and the ability to perform activities. The score ranges from 0 to 10, where 0 indicates no disability and 10 indicates death from the disease; the higher the score, the greater the disability. The EDSS is a widely used tool for monitoring MS.8

VariablesNfL levels were taken as the outcome variable. Demographic characteristics such as age, sex and cohabitation status were taken as variables included in the description, and clinical characteristics such as disease phenotype; time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis; age at diagnosis; initial symptoms by EDSS functional system; complications by functional system; disease-modifying treatment; comorbidities and their treatment, and areas with demyelinating lesions in the MRI were included.

NfL sampling and analysisAll eligible patients were taken consecutively within the study period for a total of 70 patients and 10 controls. The controls were only used to determine the baseline NfL levels and to be able to make the comparison with the levels found in the patients according to their phenotype and sex, bearing in mind that the controls were healthy patients who did not have MS.

To obtain plasma samples, patients underwent venipuncture, after obtaining informed consent, and blood was collected in sterile tubes with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid. For this procedure, a protocol agreed upon with the health institution was followed and the patients were immediately transported to the facilities of the Remington University Corporation.

The samples were centrifuged and the plasma was frozen at −70 °C until used to identify the NfL. NfL levels were measured using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Abbexa), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Lyophilized bovine NfL from UmanDiagnostics were used to generate standards ranging from 0 to 10,000 pg/mL. The mean intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation were evaluated in duplicate. A serum NfL level of 3.91 pg/mL was the analytical sensitivity of the assay, defined as the lowest calibrator concentration with precision of 80–120% and coefficients of variation determined in duplicates ≤20%.

Statistical analysisThe data were analysed in Jamovi 2.2.2. Initially an exploratory analysis of the data was performed to detect those with atypical behaviour, in addition to confirming the correct information digitalisation. The information on the qualitative variables was summarised by means of absolute and relative frequencies. For the quantitative variables central tendency and dispersion measures were presented according to their distribution using the Shapiro-Wilk test (normal or non-normal). The data were represented graphically by means of a bar chart.

ResultsSociodemographic and clinical patient characteristicsAccording to the distribution by sex, the majority of the patients, 87.14%, were women, with the median age at diagnosis at 31.5 years (IQR 24.25−42 years), 64.29% of the participants had a partner. 85.71% had the RRMS phenotype and both the PPMS and SPMS phenotypes represented 7.14%. Regarding comorbidities, 21.4% had metabolic diseases, 14.3% other diseases, 10% mental disorders and 5.71% cardiovascular diseases. Regarding the treatment of these comorbidities, 21.43% were treated with antidepressants, 17.14% with analgesics and 8.57% of patients took drugs for cardiovascular diseases (Table 1).

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients with multiple sclerosis who were part of the biomarker analysis.

| Variable | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Woman | 61 | 87.14 |

| Age at MS diagnosis (Me-IQR) | 31.50 | 24.25−42 | |

| Cohabitation status | Cohabiting with partner | 25 | 35.71 |

| RRMS | 60 | 85.71 | |

| PPMS | 5 | 7.14 | |

| SPMS | 5 | 7.14 | |

| Comorbidities | Metabolic diseases | 15 | 21.4 |

| Other diseases | 10 | 14.3 | |

| Cardiovascular diseases | 4 | 5.7 | |

| Neurological diseases | 3 | 4.3 | |

| Mental health disorders | 7 | 10.0 | |

| Cancer | 3 | 4.3 | |

| Infectious diseases | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Autoimmune diseases | 1 | 1.4 | |

| Treatment for comorbidities | Other drugs | 18 | 25.71 |

| Antidepressants | 15 | 21.43 | |

| Analgesics | 12 | 17.14 | |

| Cardiovascular drugs | 6 | 8.57 | |

| Metabolic drugs | 12 | 17.14 | |

| Vitamin supplements | 13 | 18.57 | |

| Muscle relaxant drugs | 3 | 4.29 | |

| Hypoglycaemic drugs | 2 | 2.86 |

IQR: interquartile range; Me: median; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis; RRMS: relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Regarding MRIs, it was found that 80% had lesions in the spinal cord, 70% had lesions at the periventricular level and 68.57% had juxtacortical lesions. The use of disease-modifying drugs was distributed as follows: 25.71% of patients had been prescribed natalizumab, 25.71% fingolimod, and 10% of patients had not been treated with disease-modifying drugs (Table 2).

Clinical characteristics, frequency of prescription and use of disease-modifying therapies in patients with multiple sclerosis who were part of the biomarker analysis.

| Variable | Categories | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disability progression | 9 | 12.86 | |

| Time from initial symptoms to diagnosis (Me-IQR) | 12 | 5.25−48 | |

| Initial disease symptoms | Sensitivity | 25 | 35.71 |

| Others | 23 | 32.86 | |

| Vision | 18 | 25.71 | |

| Cerebellar | 12 | 17.14 | |

| Pyramidal | 15 | 21.43 | |

| Brainstem | 1 | 1.43 | |

| Bladder-intestine | 5 | 7.14 | |

| Asymptomatic | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Complications | Vision | 34 | 48.57 |

| Cerebellar | 22 | 31.43 | |

| No complications | 16 | 22.86 | |

| Sensitivity | 15 | 21.43 | |

| Pyramidal | 12 | 17.14 | |

| Bladder-intestine | 9 | 12.86 | |

| Others | 9 | 12.86 | |

| Mental functions | 2 | 2.86 | |

| Location of MRI findings | MRI spinal cord | 56 | 80.00 |

| Periventricular MRI | 49 | 70.00 | |

| Juxtacortical MRI | 48 | 68.57 | |

| MRI cerebellum | 28 | 40.00 | |

| MRI stem | 30 | 42.86 | |

| Active lesions | 20 | 28.57 | |

| MRI optic nerves | 4 | 5.71 | |

| Disease-modifying drugs | Interferon beta-1b | 3 | 4.29 |

| Natalizumab | 18 | 25.71 | |

| No modifying treatment | 7 | 10.00 | |

| Teriflunomide | 1 | 1.43 | |

| Fingolimod | 18 | 25.71 | |

| Peginterferon | 7 | 10.00 | |

| Rebif® | 4 | 5.71 | |

| Copaxone | 2 | 2.86 | |

| Glatiramer acetate | 1 | 1.43 | |

| Rituximab | 1 | 2.86 | |

| Ocrelizumab | 4 | 5.71 |

IQR: interquartile range; Me: median; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

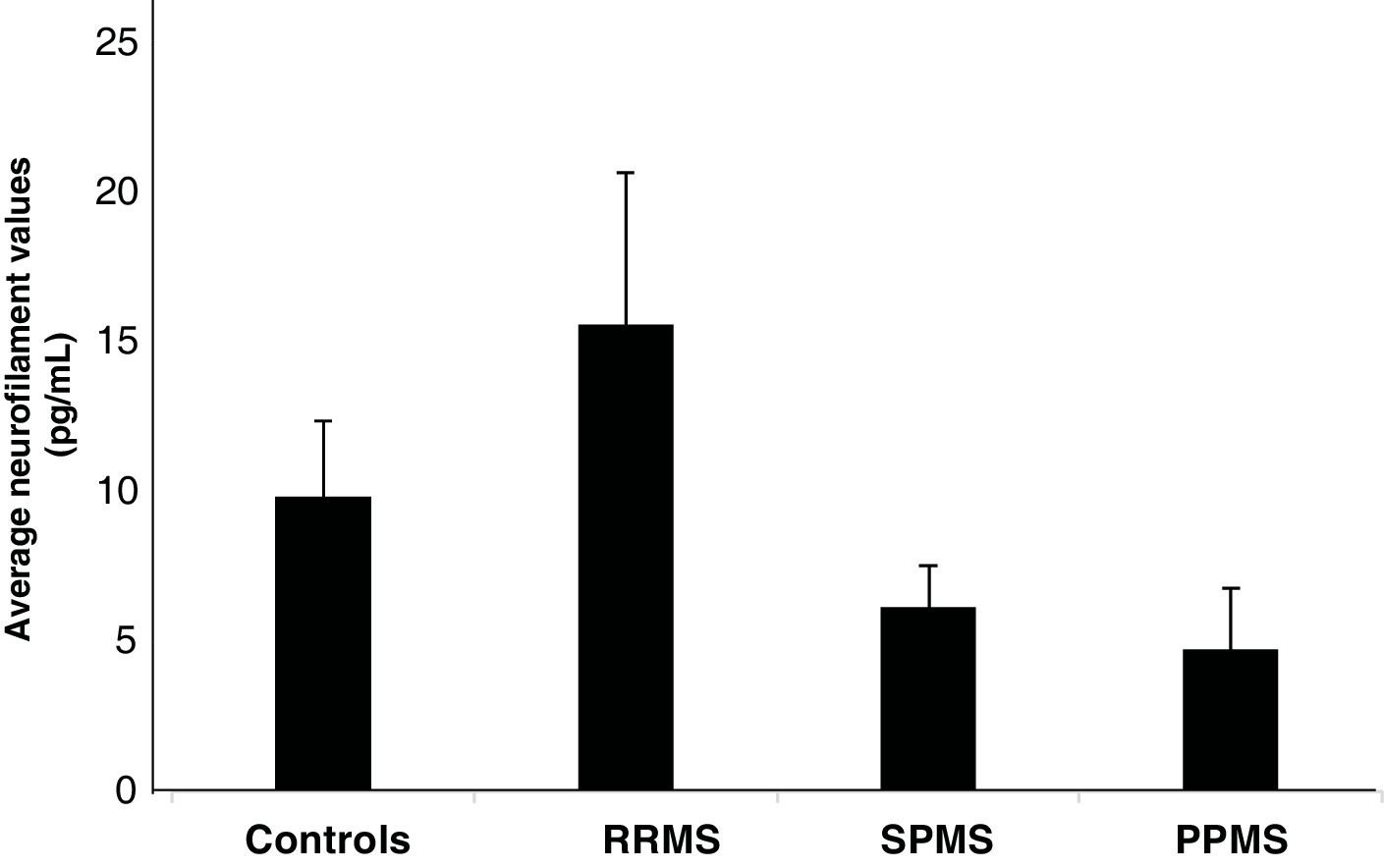

Fig. 1 illustrates the mean NfL values according to the phenotype, finding that patients with RRMS had high levels of NfL with an average of 15.74 pg/mL ± 5.10 compared to the levels of the controls, whose value was 9.83 pg/mL ± 2.54 (p = .954). The SPMS and PPMS phenotypes had values of 6.14 pg/mL ± 1.39 and 4.73 pg/mL ± 2.04, respectively, being lower than the control values (p = .611 and p = .316, respectively).

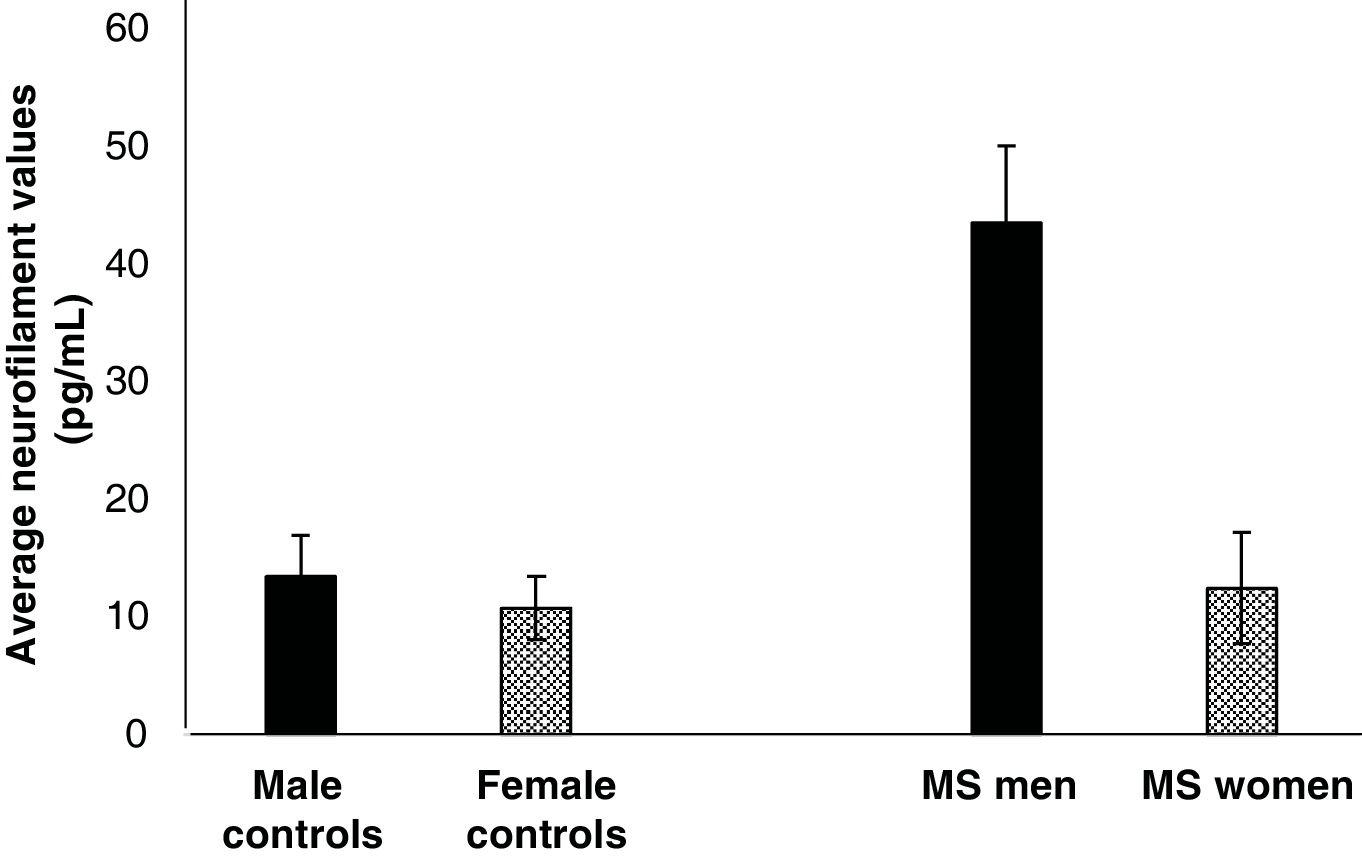

NfL levels are higher in male MS patientsOf the total number of patients who participated in the study, 12.87% were men, who had the highest NfL levels, with an average of 42.5 pg/mL ± 6.2 (Fig. 2). Women, who were the majority of the study participants (87.14%), had an average value of 22.4 pg/mL ± 4.73 (Fig. 2). When comparing Nf values between men and women with MS, no statistically significant differences were found (p = .11). Additionally, when the respective statistical comparisons were made with their controls (female controls vs. women with MS and male controls vs. men with MS), no statistically significant differences were found either (p = .22 and p = .10, respectively)

DiscussionNfs are structural proteins of the axonal cytoskeleton. They are essential for stability, radial growth, axonal calibre maintenance, and transmission of electrical impulses. Under normal conditions and in a non-linear, sex- and age-dependent manner, Nfs are constantly released from axons, reflecting normal aging. However, during axonal damage, Nf is released in greater amounts into the extracellular space, CSF, and eventually into the blood.6,7 NfL, a neuron-specific cytoskeletal protein released into the extracellular fluid after axonal injury, has been identified as a biomarker of disease activity in MS.5–7 Measuring NfL levels can flag up the extent of neuroaxonal damage, especially in the early stages of the disease. More recently, NfL levels have even been shown to facilitate individualised treatment decisions for people with MS. Our findings showed that plasma levels of NfL measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay reflect this neuroaxonal injury in MS patients, since they were detected in serum and increased specifically in the RRMS stage of the disease.

Previous studies have shown that levels of Nf in the heavy chain and NfL levels are increased in the CSF of MS cases and are possibly associated with disease severity. A moderate association between CSF NfL concentration and EDSS score has been reported in RRMS cases.9 Another study showed that the level of NfL alone, as a measurement of global neuroaxonal injury, does not seem to correctly differentiate between newly diagnosed RRMS patients and a healthy population.However, in combination with global and regional cortical thickness measurements that are considered good direct indices of cortical morphology to detect neuronal loss or degradation, both biomarkers could reveal 2 parallel pathophysiological processes underlying the neurodegenerative onset of MS and predict early cognitive deficits.10 The heterogeneity in reported data comparing NfL between PPMS and RRMS patients seems to be explained by associations with other covariates. Studies reporting higher NfL levels in RRMS compared with PPMS often included a large proportion of RRMS patients during relapses, and in studies reporting higher NfL in PPMS compared with RRMS, PPMS patients were older and a smaller proportion were on disease-modifying treatments.10,11

Our study also showed a trend towards increased NfL levels in men. According to the literature, the male sex has been shown to be one of the factors associated with a poorer disease prognosis. Although men may be 3 times less likely to develop MS than women, they are more likely to show progressive forms of the disease and to manifest brain atrophy, disability and cognitive impairment.12,13 The potential role of epigenetic modifications in the pathogenesis and progression of MS may further clarify how genetic, hormonal and environmental risk factors interact in the development of MS in men and women, and establish differences in disease incidence and progression.14

Considering that, as well as sex, there may be other factors or comorbidities, age, race, treatments, use of corticosteroids, specific to each patient, which can substantially influence NfL levels, the determination of these should not replace MRI in clinical practice. Ideally, in the future, both tools can be used in a complementary manner in patients with MS, and even other clinical criteria or other potential disease biomarkers could be taken into account. More evidence is still needed and the results of clinical trials need to be integrated to establish the usefulness of this biomarker in clinical practice.15

Finally, NfL levels are found at concentrations approximately 100 times lower in plasma compared to CSF. Therefore, the conventional enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay used in the present study has low sensitivity to detect small concentrations in serum, compared to single-molecule array technology (SiMoA®),16 and this is the main limitation of our study.

ConclusionOur research study outcomes show tendencies towards an increase in NfL levels in both the RRMS phenotype and in the male sex. These tendencies could indicate that there may be greater neuroaxonal deterioration in men who have this disease phenotype. However, studies should be conducted with a larger sample or using SiMoA® technology, which has greater detection sensitivity, to support and expand the results found in this study. It should be highlighted that this is the first study to be conducted nationally, and that our results may become an excellent precedent for future national and international studies.

Ethical considerationsThe research received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Neurological Institute of Colombia (INDEC) at its meeting on October 28, 2019, being classified as minimal risk in accordance with the provisions of Resolution 8430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia.

FundingCorporación Universitaria Remington, Universidad CES.