The literature related with the anesthetic management of emergent C section is limited, for which reason we proposed the systematic evaluation of the existing literature on anesthetic management of obstetric patients undergoing emergency cesarean section in order to define the most appropriate interventions based on evidence. A systematic review of the literature was undertaken in MEDLINE, 1966 to December 2010, Cochrane Collaboration registry of clinical trials, Cochrane systematic review database, and LILACS. The study selection process was undertaken independently by two researcher-reviewers, who identified controlled clinical trials and cohort studies of anaesthetic management in emergency C-section. The data were extracted, reviewed and subjected to quality evaluation in duplicate fashion. In total, 2,297, 36, 221 were examined, respectively, and of those 16 potentially relevant papers, 9 clinical trials and 7 observational studies were included in the study. A heterogeneity analysis was done using I2, with a result of 52%, and for this reason no meta-analysis was conducted.

ConclusionsThe anaesthetist plays a critical part in mother-and-child care, prioritization of the C-section urgency, peridural anaesthesia extension with 2% lidocaine plus adjuvants (fentanyl plus fresh adrenaline), the use of vasopressors (phenylephrine, ephedrine) for the aggressive management of hypotension, the use of oxygen supplementation and the adequate management of general anaesthesia when indicated, contributing to a favourable impact on the outcome for both the mother and the baby. Long-term neonatal outcomes are not influenced by the type of anaesthesia given to the mother.

La literatura relacionada con el manejo anestesico para cesareaurgente es escasa por lo que se propuso evaluar sistemáticamente laliteratura existente del manejo anestésico en pacientes obstétricas, sometidas a cesárea urgente con el fin de definir las intervencionesmás adecuadas basadas en la evidencia. Se realizo una revisión sistemática de la literatura en: MEDLINE, 1966 a Diciembre de 2010; Cochrane Collaboration registro de ensayos clínicos; Cochrane database de revisiones sistemáticas, LILACS. La selección de los estudios se llevo a cabo por dos investigadores-revisores de manera independiente identificaron estudios de ensayos clínicos controlados, estudios de cohorte de manejo anestésico de cesárea urgente. En duplicado, los datos fueron extraídos, revisados y evaluados en calidad. Se obtuvieron 2.297, 36, 221, 16 artículos potencialmente relevantes respectivamente, nueve ensayos clínicos y siete artículos observacionales. Se realizo un análisis de heterogeneidad utilizando I2, el cual arrojo un resultado del 52% por lo cual no se realizo metaanalisis.

ConclusionesEl anestesiólogo es parte fundamental en el cuidado del binomio madre hijo, la adecuada priorización de la urgencia en operación cesárea, la extensión anestésica peridural con lidocaína al 2% mas coadyuvantes (fentanil mas adrenalina fresca), el uso de vasopresores (fenilefrina, efedrina) para el manejo agresivo de la hipotensión, la utilización de oxigeno suplementario y un adecuado manejo de la anestesia general cuando está indicada permiten impactar favorablemente los desenlaces del binomio madre hijo. Los desenlaces neonatales a largo plazo no están influenciados por el tipo de anestesia suministrada a la madre.

It is estimated that 15% of all births occurring in the world are by C-section.1 World statistics show an increase in C-section rates of up to 60%,2,3 accounted for by an increase in high-risk pregnancies and cases in which obstetric patients present in life-threatening situations for them or for the foetus; these data indicate clearly that anaesthesia for C-section is a significant part of daily practice.4,5

There is little good quality evidence about the ideal anaesthetic technique for patients requiring emergency C-section. Traditionally, general anaesthesia has been advocated when there is immediate threat to the mother or the foetus, whereas the use of neuroaxial techniques is advocated in less pressing situations.

Given this uncertainty, NICE (National Institute For Health and Clinical Excellence) proposed a classification that allows prioritisation of the urgency of the C-section, in order to achieve the highest degree of concordance between obstetricians and anaesthetists. This classification was recently adopted as a good practice guideline by RCOG (Royal college of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists) and RCA (Royal college of Anaesthetists).6,7–11

It is important to determine what type of anaesthesia is associated with less adverse outcomes for mother and child. The goal of this paper is to perform a systematic evaluation and analysis of the existing literature on the anaesthetic management of obstetric patients requiring emergency C-section, in order to generate basic guidelines and recommendations that may contribute to a protocol approach to this issue, based on the definition of the most adequate evidence-based interventions. An additional goal is to determine the safety and effectiveness of anaesthetic interventions in terms of maternal and neonatal outcomes.

MethodsSystematic review of randomised clinical trials and observational studies.

Study criteria considered for this review- •

Type of participants: Pregnant women requiring emergency C-section.

- •

Type of measured outcomes: Primary end points.

- •

Maternal complications: Mortality, airway problems, blood loss and hypotension, intra-operative and postoperative pain, and maternal satisfaction.

- •

Neonatal complications: Mortality, one-minute and five-minute Apgar scores (activity, pulse, grimace, appearance, respiration), acid–base profile, need for Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), and learning disabilities.

- •

Secondary outcomes: Rate of conversion to another anaesthetic technique and time of establishment of the anesthetic technique.

The search strategy was developed in MEDLINE and modified for the other databases. The search was based on the PICO strategy (participants, intervention and exposure, comparison, outcomes, and study design). See: Cochrane Group methods used in reviews.11

Electronic databasesDetailed search strategies were developed for each electronic database in order to identify the studies for inclusion in this review: The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials: Cochrane Library (current issue), MEDLINE/PubMed (from 1966 to 2010), LILACS (from 1992 to 2010) and other electronic databases and grey literature.11–13

A combination of vocabulary control and free text terms was used in this search, based on the following search strategy for MEDLINE.

PICO searchP: Pregnant women undergoing emergency C-section.

I: Neuroaxial anaesthesia.

C: General anaesthesia.

O: 1. Anaesthesia failure at the start of surgery; 2. Need for a second anaesthetic technique (conversion from spinal to general), during the course of surgery; 3. Need for additional pain relief drugs during surgery: intravenous opioids or infiltration with local anaesthetics; 4. Patient dissatisfaction with the anaesthesia; 5. Time elapsed from the moment the patient arrives at the operating room and the start of the surgical procedure; 6. Neonatal adverse outcomes, including death, learning disability, low Apgar score, foetal oxygenation, acid–base profile, and admission to the NICU. Maternal adverse outcomes: death, airway problems, satisfaction, blood loss, management of hypotension after the initiation of anaesthesia, and any other secondary intervention for the management of nausea and vomiting during surgery.

The following is a description of the search strategies used in the various databases.

MEDLINE- 1.

(caesarean or emergency cesarean or caesarian or cesarian)

- 2.

(anaesthesia or anaesthesia general) and (1)

- 3.

(and spinal)

- 4.

(2 and 3)

- 5.

limit (4) to randomised controlled trial and cohort.

See Annex 1 online for search strategy.

CochraneCENTRAL and Cochrane Library, Issue 2 2010, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Trials (The Cochrane Library, Issue 2 2010), using the following terms: (cesarean-section or caesarean or cesarean or caesarian or cesarian) and (anaesthesia-obstetrical.me or anesth* or anaesth*) and (spinal).

Apart from these data, additional sources were searched for potential eligible studies, including LILACS and SciELO.

The search strategy found two recent systematic reviews14,15 though not in emergent C-section, subject matter of this research. However, they were taken into consideration as feedback for this process of evaluation and analysis. The Cochrane systematic review and the effect review summary databases (DARE) were also used in the unrestricted search for all systematic reviews associated with anaesthetic management in C-section.

No language or time restrictions were applied.

Data collection and analysisIdentification of the studiesAfter applying the search strategy described above, two researcher-reviewers, working independently, carried out the identification of the studies that met the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies between the researchers were solved by consensus and differences were solved with the involvement of a third researcher-reviewer whose role was to settle disagreements for decision making. The full text of the articles was obtained for all those that were considered suitable for review because of their inclusion criteria, title, abstract, or both. The reason for excluding studies considered for the review is detailed clearly.

Rating of the studies includedThe two researcher-reviewers, working independently, performed the analysis and evaluation of the quality of the randomized clinical trials in accordance with the following criteria: adequate randomization, masking of the assignment, adequate blinding, complete systematic follow-up, and evaluation by intention to treat. If they fulfilled all criteria, they were considered GOOD; if they fulfilled 3 or 4, they were rated FAIR; and if they fulfilled less than 3 criteria, they were rated POOR. The latter were excluded from the analysis.

Analytical observational studies were included in accordance with the following criteria: Clear definition of the objective of the study; adequate description of the target population; clear proposal for bias control; complete follow-up of the population for the proposed end points. If they fulfilled all criteria, they were considered GOOD; if they fulfilled 3 or 4, they were rated FAIR; and if they fulfilled less than 3 criteria, they were rated POOR. The latter were excluded from the analysis.

For all parameters and quality elements, definitions were used as described in the SIGN module (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network).16

Data analysisThe PICO strategy was used to obtain the data. The criteria predefined by SIGN were used to assess the quality of the studies, including systematic reviews, clinical trials, and observational studies, rated as good, fair or poor.16,17 This scale is based fundamentally on 6 criteria for systematic reviews, case-control studies, cohort studies and RCTs, respectively. A GOOD rating is given when all the criteria are met; they are rated as FAIR when 80% are met and there are no fatal flaws in the study; and the rating is POOR when less than 80% of the criteria are met, when there is a fatal error, or both.

The data were introduced into the RevMan 5 software, and a detailed description was made of each of the studies considered, including methodological development, description of the results, and conclusions or recommendations. Data were extracted by intervention assignment, independently of the performance of the assigned intervention, in order to allow for an “intention to treat” analysis. The heterogeneity analysis was performed using the I2 statistic (52.3%).18 This heterogeneity is explained by the little accuracy of the estimates and the divergent heterogeneity of the primary studies; consequently, a meta-analysis was not undertaken. Results from the controlled clinical trials and the analytical observational studies were not combined, considering that this practice is not recommended in the international literature. Likewise, there is a potential publication bias, given that the literature search was not done in EMBASE. It was not possible to obtain one of the studies included in the review,19 despite the fruitless attempt at contacting the authors.

The results of this systematic review were drafted in accordance with the PRISMA consensus (Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses).20

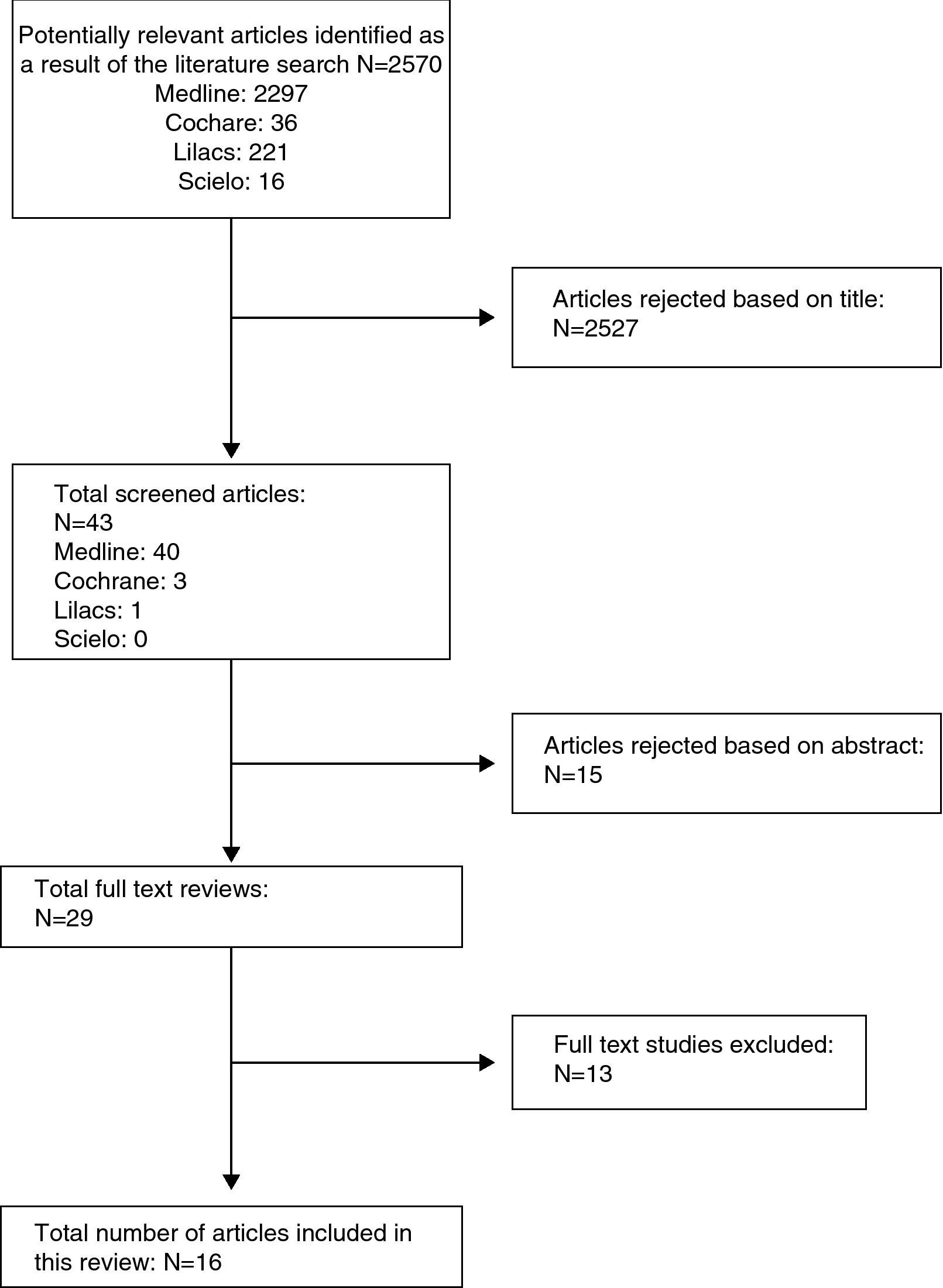

ResultsAfter adjusting the search strategy in the different databases proposed for this research, the search resulted in 2297, 36, 221, 16 potentially relevant papers found in MEDLINE, Cochrane, LILACS and Scielo, respectively. In total, 2527 were excluded due to the title and 15 due of the abstract, including for complete text evaluation a total of 29 studies, of which 13 were excluded (see Table 1). The entire process was done in a matched way, independently by researchers José Rueda and Carlos Pinzón. In those instances where there was disagreement between the two reviewers, Mauricio Vasco, a third researcher, acted as facilitator in dealing with discrepancies. Full-text review of the studies included was done using the checklists proposed by the SIGN group for clinical trials and cohort studies, and it resulted ultimately in a total of 9 studies rated as GOOD, out of which 6 are RCTs and 3 are observational analytical studies; moreover, 6 articles were rated as FAIR, of which 3 are RCTs and 3 are observational studies (Fig. 1).

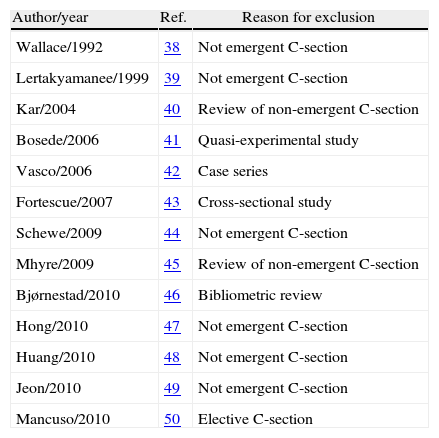

Excluded studies.

| Author/year | Ref. | Reason for exclusion |

| Wallace/1992 | 38 | Not emergent C-section |

| Lertakyamanee/1999 | 39 | Not emergent C-section |

| Kar/2004 | 40 | Review of non-emergent C-section |

| Bosede/2006 | 41 | Quasi-experimental study |

| Vasco/2006 | 42 | Case series |

| Fortescue/2007 | 43 | Cross-sectional study |

| Schewe/2009 | 44 | Not emergent C-section |

| Mhyre/2009 | 45 | Review of non-emergent C-section |

| Bjørnestad/2010 | 46 | Bibliometric review |

| Hong/2010 | 47 | Not emergent C-section |

| Huang/2010 | 48 | Not emergent C-section |

| Jeon/2010 | 49 | Not emergent C-section |

| Mancuso/2010 | 50 | Elective C-section |

Those studies selected as good and fair were included in this research as a basis for validation in order to examine the basic guidelines that need to be considered in anaesthetic management for emergent C-section determined by means of the systematic review of the literature on anaesthetic techniques for emergency C-section.

Observational studiesNine observational studies were found (seeAnnex 2), of which seven were included for the evaluation of analytical observational studies. Three cross-sectional studies21–24 with analytical component were included in the analysis because of the quality of the methodology and the objectives proposed. All cohort studies were considered.25–27

- •

Gori F, et al., 2007 (cohort).25 The main objective of this study was to assess the variables related to the anaesthetic technique and the maternal and neonatal outcomes. The study evaluated 1259 patients coming for emergency C-section, of whom 525 (41.9%) received general anaesthesia and 734 (58.1%) received regional anaesthesia. For the neonatal outcome assessed – Apgar score under 7 – the associated factors for low Apgar at 1 minute (p less than 0.01) were multiple pregnancy and general anaesthesia, and multiple pregnancy for an Apgar score less than 7 at 5 minutes (p less than 0.01).

- •

Kinsella SM, et al., 2008 (cross-sectional).23 This study reviewed 4329 pregnant women undergoing anaesthesia for emergent C-section in order to assess the type of anaesthesia used, the indication for the C-section and the type of peridural analgesia. The study found a 20% conversion rate from regional to general anaesthesia in category 1 C-section; the failure rate for pain-free surgery was 6% with spinal anaesthesia, 24% with peridural, and 18% with combined spinal-peridural anaesthesia. Apart from the type of anaesthesia and emergency surgery, a BMI greater than 27, absence of prior C-sections, and whether the indication for the procedure was unsatisfactory foetal condition or maternal comorbidities, were also associated with failure of regional anaesthesia. There is a tendency to use peridural opioid administration plus adrenaline as adjuvants to the local anaesthesia in order to ensure good-quality anaesthesia. The presence of an adequate block for C-section with low-volume local anaesthetics delivered to the peridural space was also associated with lower failure rates.

- •

Regan K, et al., 2008 (Cross-sectional).24 A survey was conducted in 209 institutions in the United Kingdom (9 exclusions), in order to determine the anaesthetic technique used for peridural anaesthetic extension in obstetric patients taken to emergent C-section. It was found that the peridural block was extended in 68% of cases in the delivery room, and the anaesthetic of choice was 0.5% bupivacaine (41%). Forty-three adverse events were reported, 26 of which corresponded to upper neuroaxial block; of these, 12 required intubation, and 8 presented inadequate neuroaxial block. In 64% of cases, there were guidelines for immediate anaesthetic management for emergency C-section.

- •

Sprung J, et al., 2009 (Cohort).26 A total of 5320 neonates were considered. Of them, 497 were delivered by C-section (elective and emergent), 193 under general anaesthesia (38.8%), and 304 under regional anaesthesia (61,2%). The primary end point analysed was “learning disability”. There was evidence that the incidence of that outcome does not depend on the route of delivery, although there is a tendency in children born to mothers under general anaesthesia to show a higher incidence of this outcome when compared to babies born to mothers receiving regional anaesthesia (HR: 0.64, 95% CI 95 0.44–0.42).

- •

Pallasmaa N, et al., 2010 (Cohort).27 The objective of the study was to determine the rate of maternal complications associated with C-section (elective and emergent), and risk factors associated with maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes. In total, 2496 pregnant women were analysed over a 6-month period, during which the rate of C-sections was 16.6%, 45.6% elective, and 7.9% emergent. The main statistically significant complications occurred in emergent C-section (42.4%), compared with elective C-section (21.3%), and they were associated with bleeding, intra-operative complications (uterine organ and vessel damage, uterine and blood vessel lacerations), anaesthetic complications, post-partum complications, infection and severe complications. Anaesthetic complications were not significant from the statistical point of view in this study, regardless of the technique (p 0.76). There was evidence that C-section (OR=1.8, 95% CI 1.5–2.1), preeclampsia (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.2–1.8), gestational age under 30 weeks (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.2–1.8), and maternal obesity defined as a body mass index (BMI) >30 (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.1–1.8) behave as risk factors for adverse maternal outcomes.

- •

Kinsella SM, 2010 (Cross-sectional).21 A questionnaire was developed and given in 245 obstetric centres in the United Kingdom, in order to evaluate adherence to the 4-grade classification for the prioritization of Emergent C-section proposed by NICE. Of the centres that received the survey, 70% responded. The percentage of general anaesthesia was 51% for emergent C-section, for emergency or elective C-section the percentage was 12%, and for category 4 elective Cesarean section, the percentage was 4%. Despite the availability of an adequate classification, adherence is not greater in specialized institutions as might be expected; however, overall, there is adequate adherence to the guidelines, but not to the recommendation regarding timing of the C-section. The rate of general anaesthesia does not change according to the institution, but the use of neuroaxial anaesthesia is greater in high complexity institutions.

- •

Chau In W, et al., 2010 (Cross-sectional).22 The study measured the incidence of maternal and neonatal complications related to the type of general anaesthesia used in patients undergoing C-section (elective and emergent), based on all the hospital records of the cases that received general anaesthesia in 18 centres. The incidence of complications with general anaesthesia was 35.9:10,000 pregnant women (95% CI 27.4–46.1). The most frequent complications included desaturation 13.8 (95% CI 8.7–20.7), cardiac arrest 10.2 (95% CI 5.9–16.3), intra-operative recall 6.6 (95% CI 3.3–11.8), and death 4.8 (95% CI 2.17–9.4). Forty-six patients (76.7%) were taken to emergency C-section, and 68.4% of them received general anaesthesia. During pre-anaesthetic assessment, predictors of a difficult airway were identified in 14% of the patients.

Studies of patients undergoing emergent C-section and that may be classified in several categories were analysed. Patients diagnosed with severe preeclampsia scheduled for emergent C-section under regional or general anaesthesia28,29; patients receiving peridural analgesia for labour who were scheduled for emergent C-section with anaesthetic extension using a peridural catheter30–34; selection of vasopressor for the treatment of hypotension in emergent C-section under regional anaesthesia35; and impact of maternal oxygen supplementation on neonatal outcomes in mothers undergoing emergent C-section under regional anaesthesia36 (see Annex 3).

- •

Wallace D, et al., 1995.28 This study assessed maternal and neonatal outcomes in 80 patients with severe preeclampsia taken to emergency C-section under three anaesthetic techniques – general, peridural, or combined spinal-peridural. No differences were found in terms of maternal or neonatal outcomes between the three groups.

- •

Dyer R, et al., 2003. This study randomised 70 patients diagnosed with severe preeclampsia scheduled for emergent C-section due to unsatisfactory foetal condition, under spinal or general anaesthesia. The study found that maternal outcomes did not change, but foetal outcomes in the group receiving spinal anaesthesia were statistically significant with a higher base deficit (7.13mequiv./l vs. 4.68mequiv./l, p=0.02) and a lower neonatal umbilical artery pH (7.20 vs. 7.23, p=0.046). The clinical implications of this foetal acidosis in the patients who received spinal anaesthesia are still to be determined.

- •

Goring-Morris J, et al., 2006.30 This study assessed 68 patients coming with a continuous infusion of peridural analgesia for labour consisting of a mix of local anaesthetic plus opioid (0.1% bupivacaine+fentanyl 2mcg/cc), who were scheduled for emergent C-section categories 2–3 (NICE). Patients were randomised to receive peridural anaesthesia with 20cc of 2% lidocaine plus adjuvants (fentanyl and adrenaline), vs. 20cc of 0.5% bupivacaine. No statistically significant differences were found for maternal or foetal outcomes, and lidocaine is less expensive and less toxic than bupivacaine.

- •

Malhotra S, et al., 2007.31 This study assessed 105 patients who came with peridural analgesia for labour consisting of a mix of local anaesthetic plus opioid in intermittent 10–15cc boluses (0.1% bupivacaine+fentanyl 2mcg/cc), who were scheduled for emergency C-section categories 2–3 (NICE). It compared the efficacy of adding fentanyl 75mcg to the dose of local anaesthetic (20cc of 0.5% levobupicaine) for peridural anaesthetic extension for C-section. No differences were found in terms of timing of the pharmacological initiation or supplementation during C-section. The study had to be interrupted because of an increased incidence of maternal nausea and vomiting, in the group that received fentanyl (53% vs.18%; p=0.004).

- •

Sng BL, et al., 2008.32 This study assessed 90 patients who came with labour analgesia instituted using the spinal-peridural technique (spinal with ropivacaine 2mg and fentanyl 15mcg) and went on to receive peridural infusion of a mix of local anaesthetic plus opioid (0.1% ropivacaine+fentanyl 2mcg/cc at 10cc/h). It compared the efficacy of the new local anaesthetics – 0.75% ropivacaine, 0.5% levobupivacaine – for anaesthetic extension through the peridural catheter, with the more traditional anaesthetic technique using 20cc of 2% lidocaine plus adjuvants (fentanyl and adrenaline) for emergent C-section categories 2–3 (NICE). No statistical differences were found in maternal or foetal outcomes.

- •

Allam J, et al., 2008.33 This study assessed 46 patients (6 excluded) coming with peridural analgesia for labour using a mix of local anaesthetic plus opioid (0.1% bupivacaine+fentanyl 2mcg/cc) delivered by patient controlled analgesia pump (PCA) programmed as follows: 5cc boluses with 15 minute blockade intervals, and basal infusion at a rate of 3cc/h. When patients were scheduled for emergent C-section categories 2–3 (NICE), they were randomised to two groups for anaesthesia extension using peridural catheter, as follows: group 1, lidocaine-bicarbonate-adrenaline at final concentrations of 1.8%, 0.76% and 1:200,000, respectively, for a total volume of 20.1cc; and group 2, 20cc of 0.5% levobupivacaine (no peridural fentanyl was used in either group). Latency was reduced significantly in group 1 (lidocaine-bicarbonate-adrenaline) with a time median (IQR [range]) to reach blockade, assessed by touch on dermatome T5 and cold on dermatome T4, respectively, of 7 (6–9 [5–17]) minutes and 7 (5–8 [4–17]) minutes, compared to group 2 (levobupivacaine) where the times were 14 (10)17 [9–31]) minutes and 11 (9–14 [6–30]) minutes (p=0.00004 and 0.001, respectively). There was a tendency to greater maternal sedation in group 1, although it was not statistically significant.

- •

Ngan Kee WD, et al., 2008.35 This trial studied 204 patients scheduled for peridural emergent C-section categories 2–3 (NICE) using a standardized spinal anaesthesia technique. Patients who had been receiving peridural analgesia for labour were not included, and the remaining were randomised to receiving parenteral vasopressors in case of hypotension (systolic blood pressure <100mmHg), as follows: group 1, phenylephrine 100mcg, and group, 2 ephedrine 10mg. Maternal and neonatal outcomes were assessed but no statistical differences were found. The authors concluded that both phenylephrine as well as ephedrine, under the conditions of this trial, are eligible vasopressors for the management of hypotension in patients undergoing emergent C-section under a standardized protocol for spinal anaesthesia.

- •

Balaji P, et al., 2009.34 This study assessed 100 patients coming with peridural analgesia for labour consisting of a mix of local anaesthetic plus opioid given as intermittent bolus (0.1% bupivacaine+fentanyl 2mcg/cc), who were scheduled for emergent C-section categories 2–3 (NICE). Patients were randomised to receive 20cc of 2% lidocaine with adjuvants (fentanyl and adrenaline), vs. 20cc of 0.5% levobupivacaine delivered by means of a peridural anaesthetic technique. The solution of 2% lidocaine with adjuvants resulted in a better-quality blockade with a faster onset of action when compared with the use of 0.5% levobupivacaine in anaesthesia for C-section.

- •

Khaw KS, et al.36 The authors randomised 125 patients scheduled for emergent C-section categories 2–3 (NICE) under regional anaesthesia (anaesthetic peridural, spinal, or combined spinal/peridural extension) to receive oxygen supplementation at different inspired fractions of oxygen, in order to assess the neonatal risk associated with lipid peroxidation. The authors found that 60% oxygen supplementation given to patients undergoing emergent C-section increases foetal oxygenation – UA (uterine artery) PO2 [mean 2.2 (DS0.5)kPa vs. 1.9 (0.6)kPa, p<0.01]; UA (uterine artery) O2 content [6.6 (2.5)cc/dl vs. 4.9 (2.8)cc/dl, p<0.006]; UV (uterine vein) PO2 [3.8 (0.8)kPa vs. 3.2 (0.8)kPa, p<0.0001]; and UV (uterine vein) O2 [12.9 (3.5)cc/dl vs. 10.4 (3.8)cc/dl, p<0.001]. No statistically significant differences were found in 8-isoprostane plasma concentrations. The authors conclude that inspired fractions of 60% oxygen in mothers taken to emergent C-section under regional anaesthesia increase foetal oxygenation with no additional neonatal risk of lipid peroxidation.

Emergent C-section requires adequate prioritization. We suggest implementing the NICE scale6,7,10,37 because it improves communication in the work team, helps identify those cases that need to be delivered immediately (category 1), reduces potential risks for the mother by avoiding the routine use of general anaesthesia in emergency cases, and facilitates audit and tabulation.3,21,23,29,30,32 This classification was recently adopted as a good practice guideline by RCOG and RCA.11

The following are the options in the setting of patients scheduled for emergent C-section, NICE categories 2 and 3, who come with peridural catheter analgesia for labour: 2% lidocaine in a mean volume of 20cc is the local anaesthetic of choice for peridural anaesthetic extension because of its low neurologic and cardiovascular toxicity and its cost-effectiveness, when compared with other local anaesthetics (0.5% bupivacaine, 0.5% levobupivacaine and 2% ropivacaine)30–34; fentanyl (75 and 100mcg) and fresh adrenaline (1 in 200,000), as peridural adjuvants, shorten the latency of the local anaesthetic and improve the quality of the peridural block.30,31,34 The use of 0.76% bicarbonate as adjuvant with 2% lidocaine did not shorten the latency or improve the quality of the peridural block.33

In patients scheduled for emergent C-section without peridural catheter for analgesia, the options are to provide spinal anaesthesia or use a peridural technique. The advantages of the former include avoiding the risks associated with airway management, reducing the risk of post-operative bleeding, improving the Apgar score at one minute when compared with general anaesthesia, and favouring early maternal-neonatal bonding. The disadvantages include a higher incidence of foetal acidosis,29 and delayed delivery due to the technical difficulties. The disadvantages of the peridural technique in an urgent setting include prolonged latency time for the onset of action and inadequate blockade, higher rates of intraoperative pain and the need to add systemic agents and/or convert to a different anaesthetic technique.22 Another option is to use combined peridural-spinal techniques, which have the advantage of the profound block of the spinal technique plus the probability of anaesthetic support of the peridural catheter in the event the procedure is prolonged. The disadvantages include longer placement time, greater intra-operative pain and the need to add systemic agents or convert to a different anaesthetic technique, when compared to spinal anaesthesia. Finally, the use of general anaesthesia offers the advantage of rapid onset of action and better foetal oxygenation profiles, but there are disadvantages, including maternal difficulties associated with airway management and a higher risk of intra-operative bleeding, and lower neonatal Apgar scores at one minute, when compared with neuroaxial techniques.22,24 In contrast, Gori and Pallasmaa25,27 found that adverse maternal outcomes, such as complications associated with airway management and intraoperative bleeding, did not correlate with the type of anaesthesia used, but are rather associated with the patient's clinical conditions such as the degree of emergency of the C-section (greater if emergent), obesity, gestational age under 30 weeks, and preeclampsia.

Regional anaesthetic techniques are not absolutely contraindicated in patients taken to urgent C-section. The choice of the technique is influenced by maternal comorbidities, the degree of urgency, the hemodynamic status of the patient, and the skill of the operator. In the event a spinal technique is chosen, vasopressors are used as first line choice for the management of hypotension. Ngan35 assessed outcomes and concluded that phenylephrine as well as ephedrine are eligible vasopressors for the management of hypotension in patients taken to urgent C-section under a standardized spinal anaesthesia protocol. The use of oxygen supplementation in inspired fractions of 60% oxygen improve foetal oxygenation parameters, without increasing the risk of lipid peroxidation in patients taken to urgent C-section under spinal anaesthesia.36

In patients with severe preeclampsia taken to emergency C-section, regional techniques are not contraindicated in the absence of maternal coagulopathy. The mothers show a favourable hemodynamic profile when compared with the general anaesthesia technique; neonates born to mothers in whom spinal techniques were used showed foetal acidosis parameters in cord blood, attributed to the use of ephedrine as vasopressor for the treatment of hypotension.28,29 Development and learning abnormalities that may occur in neonates with acid–base alterations in cord blood gases with no Apgar compromise are still to be defined. Sprung26 studied whether there was a correlation between exposure to a certain type of anaesthesia and learning disabilities, and found that although 68% of urgent C-sections were done under general anaesthesia, the neonates in this group did not show development alterations when compared to those delivered under regional anaesthesia. Consequently, the conclusion is that the type of anaesthesia does not influence learning disabilities when compared to babies born after vaginal delivery. In conclusion, the anaesthetist is a key member of the team in charge of providing care to the mother and the baby. The use of a classification that enables adequate prioritization of the urgency in urgent C-section, peridural anaesthesia extension with 2% lidocaine plus adjuvants (fentanyl plus fresh adrenaline), the aggressive use of vasopressors (phenylephrine, ephedrine) for the management of hypotension, the use of oxygen supplementation (inspired oxygen fractions greater than 60%), and an adequate management of general anaesthesia whenever it is indicated, all have a positive impact on maternal and foetal outcomes. Long-term foetal outcomes are not influenced by the type of anaesthesia given to the mother.

Source of fundingAuthors’ own resources.

Conflict of interestNone declared.

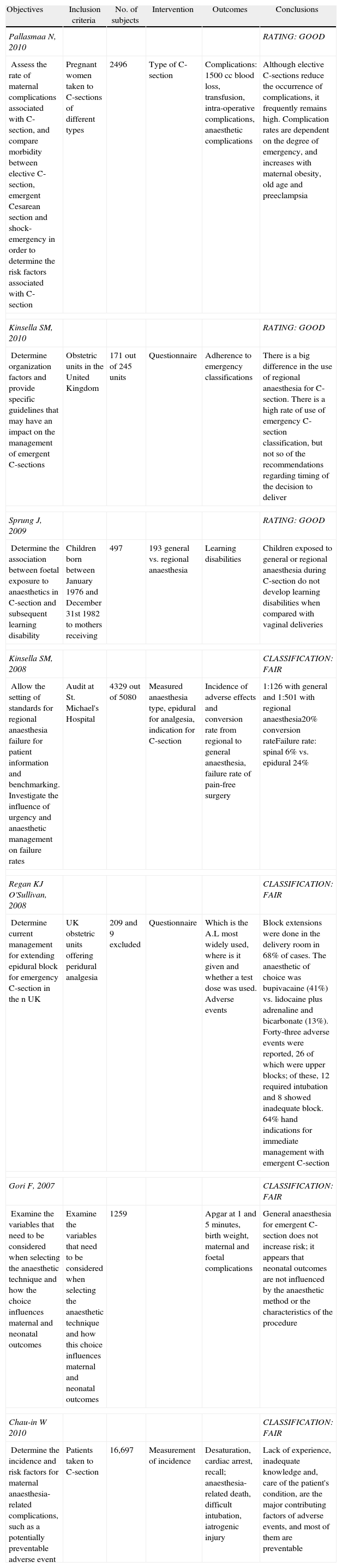

| Objectives | Inclusion criteria | No. of subjects | Intervention | Outcomes | Conclusions |

| Pallasmaa N, 2010 | RATING: GOOD | ||||

| Assess the rate of maternal complications associated with C-section, and compare morbidity between elective C-section, emergent Cesarean section and shock-emergency in order to determine the risk factors associated with C-section | Pregnant women taken to C-sections of different types | 2496 | Type of C-section | Complications: 1500cc blood loss, transfusion, intra-operative complications, anaesthetic complications | Although elective C-sections reduce the occurrence of complications, it frequently remains high. Complication rates are dependent on the degree of emergency, and increases with maternal obesity, old age and preeclampsia |

| Kinsella SM, 2010 | RATING: GOOD | ||||

| Determine organization factors and provide specific guidelines that may have an impact on the management of emergent C-sections | Obstetric units in the United Kingdom | 171 out of 245 units | Questionnaire | Adherence to emergency classifications | There is a big difference in the use of regional anaesthesia for C-section. There is a high rate of use of emergency C-section classification, but not so of the recommendations regarding timing of the decision to deliver |

| Sprung J, 2009 | RATING: GOOD | ||||

| Determine the association between foetal exposure to anaesthetics in C-section and subsequent learning disability | Children born between January 1976 and December 31st 1982 to mothers receiving | 497 | 193 general vs. regional anaesthesia | Learning disabilities | Children exposed to general or regional anaesthesia during C-section do not develop learning disabilities when compared with vaginal deliveries |

| Kinsella SM, 2008 | CLASSIFICATION: FAIR | ||||

| Allow the setting of standards for regional anaesthesia failure for patient information and benchmarking. Investigate the influence of urgency and anaesthetic management on failure rates | Audit at St. Michael's Hospital | 4329 out of 5080 | Measured anaesthesia type, epidural for analgesia, indication for C-section | Incidence of adverse effects and conversion rate from regional to general anaesthesia, failure rate of pain-free surgery | 1:126 with general and 1:501 with regional anaesthesia20% conversion rateFailure rate: spinal 6% vs. epidural 24% |

| Regan KJ O'Sullivan, 2008 | CLASSIFICATION: FAIR | ||||

| Determine current management for extending epidural block for emergency C-section in the n UK | UK obstetric units offering peridural analgesia | 209 and 9 excluded | Questionnaire | Which is the A.L most widely used, where is it given and whether a test dose was used. Adverse events | Block extensions were done in the delivery room in 68% of cases. The anaesthetic of choice was bupivacaine (41%) vs. lidocaine plus adrenaline and bicarbonate (13%). Forty-three adverse events were reported, 26 of which were upper blocks; of these, 12 required intubation and 8 showed inadequate block. 64% hand indications for immediate management with emergent C-section |

| Gori F, 2007 | CLASSIFICATION: FAIR | ||||

| Examine the variables that need to be considered when selecting the anaesthetic technique and how the choice influences maternal and neonatal outcomes | Examine the variables that need to be considered when selecting the anaesthetic technique and how this choice influences maternal and neonatal outcomes | 1259 | Apgar at 1 and 5minutes, birth weight, maternal and foetal complications | General anaesthesia for emergent C-section does not increase risk; it appears that neonatal outcomes are not influenced by the anaesthetic method or the characteristics of the procedure | |

| Chau-in W 2010 | CLASSIFICATION: FAIR | ||||

| Determine the incidence and risk factors for maternal anaesthesia-related complications, such as a potentially preventable adverse event | Patients taken to C-section | 16,697 | Measurement of incidence | Desaturation, cardiac arrest, recall; anaesthesia-related death, difficult intubation, iatrogenic injury | Lack of experience, inadequate knowledge and, care of the patient's condition, are the major contributing factors of adverse events, and most of them are preventable |

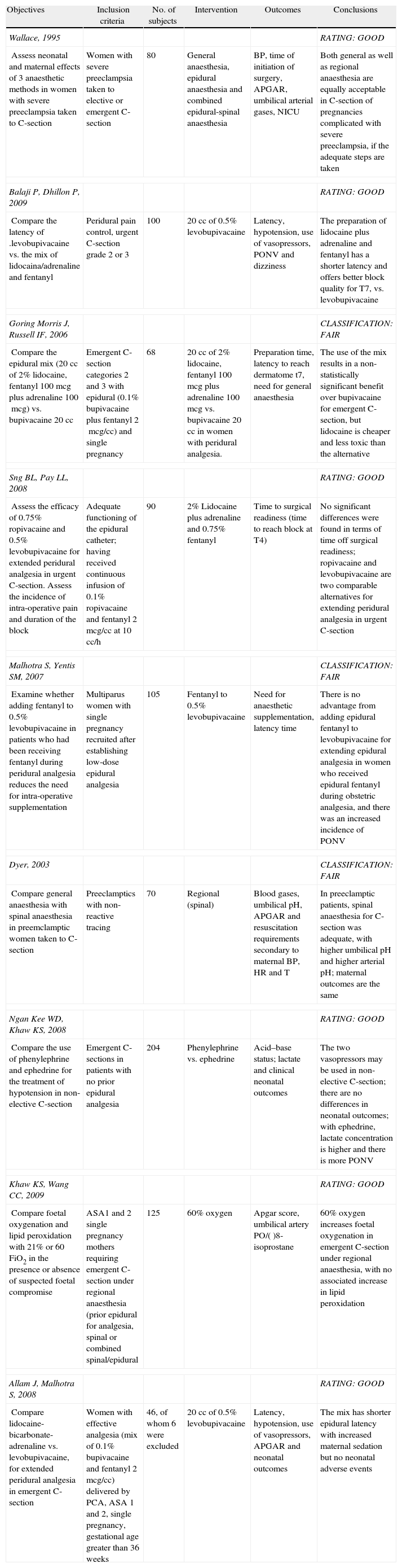

| Objectives | Inclusion criteria | No. of subjects | Intervention | Outcomes | Conclusions |

| Wallace, 1995 | RATING: GOOD | ||||

| Assess neonatal and maternal effects of 3 anaesthetic methods in women with severe preeclampsia taken to C-section | Women with severe preeclampsia taken to elective or emergent C-section | 80 | General anaesthesia, epidural anaesthesia and combined epidural-spinal anaesthesia | BP, time of initiation of surgery, APGAR, umbilical arterial gases, NICU | Both general as well as regional anaesthesia are equally acceptable in C-section of pregnancies complicated with severe preeclampsia, if the adequate steps are taken |

| Balaji P, Dhillon P, 2009 | RATING: GOOD | ||||

| Compare the latency of .levobupivacaine vs. the mix of lidocaina/adrenaline and fentanyl | Peridural pain control, urgent C-section grade 2 or 3 | 100 | 20cc of 0.5% levobupivacaine | Latency, hypotension, use of vasopressors, PONV and dizziness | The preparation of lidocaine plus adrenaline and fentanyl has a shorter latency and offers better block quality for T7, vs. levobupivacaine |

| Goring Morris J, Russell IF, 2006 | CLASSIFICATION: FAIR | ||||

| Compare the epidural mix (20cc of 2% lidocaine, fentanyl 100mcg plus adrenaline 100mcg) vs. bupivacaine 20cc | Emergent C-section categories 2 and 3 with epidural (0.1% bupivacaine plus fentanyl 2mcg/cc) and single pregnancy | 68 | 20cc of 2% lidocaine, fentanyl 100mcg plus adrenaline 100mcg vs. bupivacaine 20cc in women with peridural analgesia. | Preparation time, latency to reach dermatome t7, need for general anaesthesia | The use of the mix results in a non-statistically significant benefit over bupivacaine for emergent C-section, but lidocaine is cheaper and less toxic than the alternative |

| Sng BL, Pay LL, 2008 | RATING: GOOD | ||||

| Assess the efficacy of 0.75% ropivacaine and 0.5% levobupivacaine for extended peridural analgesia in urgent C-section. Assess the incidence of intra-operative pain and duration of the block | Adequate functioning of the epidural catheter; having received continuous infusion of 0.1% ropivacaine and fentanyl 2mcg/cc at 10cc/h | 90 | 2% Lidocaine plus adrenaline and 0.75% fentanyl | Time to surgical readiness (time to reach block at T4) | No significant differences were found in terms of time off surgical readiness; ropivacaine and levobupivacaine are two comparable alternatives for extending peridural analgesia in urgent C-section |

| Malhotra S, Yentis SM, 2007 | CLASSIFICATION: FAIR | ||||

| Examine whether adding fentanyl to 0.5% levobupivacaine in patients who had been receiving fentanyl during peridural analgesia reduces the need for intra-operative supplementation | Multiparus women with single pregnancy recruited after establishing low-dose epidural analgesia | 105 | Fentanyl to 0.5% levobupivacaine | Need for anaesthetic supplementation, latency time | There is no advantage from adding epidural fentanyl to levobupivacaine for extending epidural analgesia in women who received epidural fentanyl during obstetric analgesia, and there was an increased incidence of PONV |

| Dyer, 2003 | CLASSIFICATION: FAIR | ||||

| Compare general anaesthesia with spinal anaesthesia in preemclamptic women taken to C-section | Preeclamptics with non-reactive tracing | 70 | Regional (spinal) | Blood gases, umbilical pH, APGAR and resuscitation requirements secondary to maternal BP, HR and T | In preeclamptic patients, spinal anaesthesia for C-section was adequate, with higher umbilical pH and higher arterial pH; maternal outcomes are the same |

| Ngan Kee WD, Khaw KS, 2008 | RATING: GOOD | ||||

| Compare the use of phenylephrine and ephedrine for the treatment of hypotension in non-elective C-section | Emergent C-sections in patients with no prior epidural analgesia | 204 | Phenylephrine vs. ephedrine | Acid–base status; lactate and clinical neonatal outcomes | The two vasopressors may be used in non-elective C-section; there are no differences in neonatal outcomes; with ephedrine, lactate concentration is higher and there is more PONV |

| Khaw KS, Wang CC, 2009 | RATING: GOOD | ||||

| Compare foetal oxygenation and lipid peroxidation with 21% or 60 FiO2 in the presence or absence of suspected foetal compromise | ASA1 and 2 single pregnancy mothers requiring emergent C-section under regional anaesthesia (prior epidural for analgesia, spinal or combined spinal/epidural | 125 | 60% oxygen | Apgar score, umbilical artery PO/()8-isoprostane | 60% oxygen increases foetal oxygenation in emergent C-section under regional anaesthesia, with no associated increase in lipid peroxidation |

| Allam J, Malhotra S, 2008 | RATING: GOOD | ||||

| Compare lidocaine-bicarbonate-adrenaline vs. levobupivacaine, for extended peridural analgesia in emergent C-section | Women with effective analgesia (mix of 0.1% bupivacaine and fentanyl 2mcg/cc) delivered by PCA, ASA 1 and 2, single pregnancy, gestational age greater than 36 weeks | 46, of whom 6 were excluded | 20cc of 0.5% levobupivacaine | Latency, hypotension, use of vasopressors, APGAR and neonatal outcomes | The mix has shorter epidural latency with increased maternal sedation but no neonatal adverse events |

Please cite this article as: Rueda Fuentes JV, et al. Manejo anestésico para operación cesárea urgente: revisión sistemática de la literatura de técnicas anestésicas para cesárea urgente. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2012;40:273–86.