Eating disorders (EDs) are complex conditions of multifactorial origin. Their main characteristic is excessive concern about body weight and shape, which causes great discomfort and physical problems and leads to a decrease in quality of life and alterations in the patient’s functionality social environment. The objective of this study is to describe the emotional and behavioural symptoms of adolescents who consult a specialised ED programme in the city of Bogota.

MethodsObservational, descriptive, cross-sectional study, for which patients between 11 and 19 years old with an ED diagnosis were recruited.

ResultsForty patients with an ED diagnosis were included, of which 92% were female. The mean age of the patients was 16.6±1.9 years; 57% of patients live in a two-parent home and 30% in a single-parent home; 72% of the sample had excellent academic performance; 50% were moderately ill; 60% received pharmacological management with SSRIs; 65% of patients met clinical criteria for anxiety disorder, 30% for depressive disorder; 22.5% had aggression problems; 17.5% criminal behaviour; 72.5% of the sample met clinical criteria for internalising symptoms and 42.5% for externalising symptoms, the majority being patients with a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa.

ConclusionsPatients with bulimia nervosa obtained higher scores in the different emotional and behavioural symptoms than those with other eating disorders. This condition is associated with greater psychopathology, which must be examined rigorously at the time of clinical care, seeking to reduce the functional impact that these symptoms generate on the individual.

Los trastornos de la conducta alimentaria (TCA) son afecciones complejas de origen multifactorial que tienen como principal característica la preocupación excesiva por el peso y la forma del cuerpo, que causa gran malestar y afectación física y lleva a una disminución de la calidad de vida y alteraciones de la funcionalidad del paciente y su entorno social. El objetivo de este estudio es describir los síntomas de orden emocional y conductual de los adolescentes que consultan en la ciudad de Bogotá a un programa especializado en TCA.

MétodosEstudio observacional y descriptivo de corte transversal, para el que se reclutó a pacientes de 11-19 años con diagnóstico de TCA.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 40 pacientes con diagnóstico de TCA, el 92% mujeres. El promedio de edad de los pacientes fue 16,6±1,9 años. El 57% de los pacientes viven en hogar biparental y el 30%, en hogar monoparental. El 72% de la población tenía un rendimiento académico excelente. El 50% de los pacientes estaban moderadamente enfermos. El 60% estaba en tratamiento farmacológico con ISRS. El 65% de los pacientes cumplían criterios clínicos de trastorno de ansiedad; el 30%, de trastorno depresivo; el 22,5%, de problemas de agresividad, y el 17,5%, de conducta delictiva. El 72,5% de la muestra muestra criterios clínicos de síntomas internalizantes y el 42,5%, de síntomas externalizantes, y la mayoría de ellos son pacientes con diagnóstico de bulimia nerviosa.

ConclusionesLos pacientes con bulimia nerviosa obtuvieron en los diferentes síntomas de orden emocional y conductual puntuaciones superiores que con los demás trastornos alimentarios. Esta entidad ofrece mayor psicopatología, la cual se debe examinar rigurosamente al momento de la atención clínica, buscando disminuir el impacto funcional que estos síntomas generan en el individuo.

Eating disorders (ED) are complex conditions of multifactorial origin. Their main feature is excessive preoccupation with body weight and shape, which leads to the onset of body image distortion. These disorders are accompanied by voluntary food restriction or binge eating, which cause great discomfort and physical problems, altering the patient’s functionality and social environment.1 Their onset tends to be during adolescence and they predominantly affect females. However, some studies indicate that these symptoms appear more often before puberty and in males.2 Awareness of the psychopathology associated with these disorders has recently gained greater importance. One study found that 94.5% of patients with bulimia nervosa (BN), 76.5% of patients with binge-eating disorder and 56.2% of those with anorexia nervosa (AN) met at least one diagnostic criterion in Axis I. Eating disorders are positively associated with almost all of the DSM-IV core symptoms of mood disorders, anxiety, impulse control disorder and substance use.5

Statistics on the prevalence of eating disorders in Colombia are unknown and only partial data are available from studies conducted in community populations at universities and colleges around the country, such as the study conducted in Bogotá, to determine the frequency of eating disorders, onset and maintenance factors and comorbidities in a population of 937 students aged 12–20 years. A total of 141 probable cases of eating disorders were detected and 53.7% of these met clinical criteria for eating disorders, with odds ratio (OR)=3.91 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 2.62–5.84) for comorbidity with depressive symptoms and OR=4.87 (95% CI, 3.27–7.29) for comorbidity with anxious symptoms.2 Another cross-sectional study used the EDI-2 questionnaire to determine risk factors for eating disorders in 481 students from three private girls schools in the city of Manizales. Some 24.7% of respondents had risk factors for eating disorders, including: alcohol abuse, family history, perception of being overweight, family functioning and body mass index (BMI)3 (Tables 1 and 2).

Distribution according to eating disorder and presence of internalising symptoms.

| Clinical range | Normal range | Clinical risk | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating disorder diagnosis | Anorexia nervosa | 15 | 4 | 1 | 20 |

| Bulimia nervosa | 12 | 2 | 1 | 15 | |

| Eating disorder not otherwise specified | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |

| Binge-eating disorder | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Total | 29 | 8 | 3 | 40 |

Distribution according to eating disorder and presence of externalising symptoms.

| Clinical range | Normal range | Clinical risk | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eating disorder diagnosis | Anorexia nervosa | 8 | 7 | 5 | 20 |

| Bulimia nervosa | 7 | 4 | 4 | 15 | |

| Eating disorder not otherwise specified | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | |

| Binge-eating disorder | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| Total | 17 | 14 | 9 | 40 | |

The 2015 Colombian National Mental Health Survey described the main mental disorders affecting the Colombian population, considering age group and prevalence over the last 30 days and over the past year. During adolescence, the prevalence of a mental disorder was 7.2% and the most common disorders were anxiety disorders (5%),4 which is consistent with global statistics. Due to the low prevalence of eating disorders in the world and the limited number of studies conducted in Colombia on this topic, the latest National Mental Health Survey focused research on risky eating behaviours, which are closely related to eating disorders. On considering the overall results obtained for the group of adolescents surveyed, it was found that 9.5% of males and 8.8% of females reported some kind of risky eating behaviour. However, the prevalence of adolescents with 2 or more risky eating behaviours is only 2.7%, which is close to international figures for eating disorders.4 Young adults from Bogotá reported the highest prevalence of risky eating disorders (11.4%; 95% CI, 9.0%–14.4%), followed by those from the Atlantic region (10.1%; 95% CI, 8.4%–12.2%).4 In Latin America, and particularly Colombia, there are no studies in adolescent populations diagnosed with eating disorders that describe the psychiatric symptoms associated with these disorders. Therefore, in order to find out more about these symptoms, it is extremely important not only to understand the epiphenomena of the disorder but also to implement and develop a more effective long-term multidisciplinary therapy, including early detection and treatment of associated psychiatric symptoms, which cause high morbidity rates and are a challenge when it comes to treating these conditions.

The objective of this study is to describe the different emotional and behavioural symptoms experienced by the population of adolescents with eating disorders attending a specialised centre for treatment.

MethodsThis cross-sectional, descriptive, observational study was conducted to describe the emotional and/or behavioural symptoms associated with eating disorders (anorexia, bulimia, binge-eating disorder and ED-NOS) in adolescents treated in a specialised programme. The study population included adolescent patients aged 11–19 years who were diagnosed with an eating disorder (anorexia, bulimia, binge-eating disorder and ED-NOS) and treated in a specialised eating disorder programme at a paediatric pre-paid medicine clinic in Bogotá, and who attended the clinic between August and December 2018. Their eating disorder was diagnosed by a psychiatry specialist (with eating disorder training) and/or the therapeutic team, considering the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-5.

The factors analysed were: sociodemographic (age, gender, level of education, people the patient lives with); anthropometric measurements (height, weight, body mass index [BMI]); eating disorder diagnosis-related factors (type of diagnosis, time since diagnosis, medical comorbidity, psychiatric comorbidity) and treatment-related factors (drug treatment, treatment modality, treatment duration).

InstrumentsVariables measured by the Youth Self-Report (YSR) (total score, internalising dimension, externalising dimension) in relation to functioning (Clinical Global Impression scale) are based on data obtained from the interview and mental examination. Data on the mentioned variables were collected via a structured questionnaire with basic demographic data, anthropometric measurements and information on the eating disorder. Furthermore, all patients answered the YSR, which is divided into two parts: the first evaluates sporting, social and academic skills and competencies; and the second consists of 112 questions, of which 16 evaluate adaptive or pro-social behaviour, while the rest concentrate on a wide range of problematic behaviours. Psychopathological symptoms are divided into 9 syndromes: depression, verbal aggression, delinquent behaviour, conduct disorder, thought problems, social relations problems, somatic complaints, attention problems and phobic/anxious behaviours. These syndromes are classified into 2 large categories. The first is the internalising category, which implies the presence of psychological stress within the subject. This is related to symptoms of distress, depression and low mood and would include the syndromes of depression/withdrawal, somatic complaints and anxiety. The second is the externalising category, which is aimed at others with the hope of disrupting other people. It is related to symptoms of aggression, attention deficit, hyperactivity and disorganised behaviour and would include the syndromes of delinquent behaviour and conduct disorder. This questionnaire has been validated in studies conducted in Latin America.5,6

Statistical analysisThe IBM SPSS® software was used for the statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were calculated using contingency tables to obtain measures of central tendency and dispersion. For numerical variables, averages were obtained and for categorical variables, percentages were obtained.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the independent ethics committee of a university in Bogotá. All participants gave their assent and informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardian of the children. The confidentiality of and respect for the information provided were guaranteed.

The study had a selection bias since only the population attending a specialised eating disorder programme was invited to participate. In order to minimise other biases, investigators directly responsible for applying the instruments resolved any queries in order to avoid distortion in the understanding of questions.

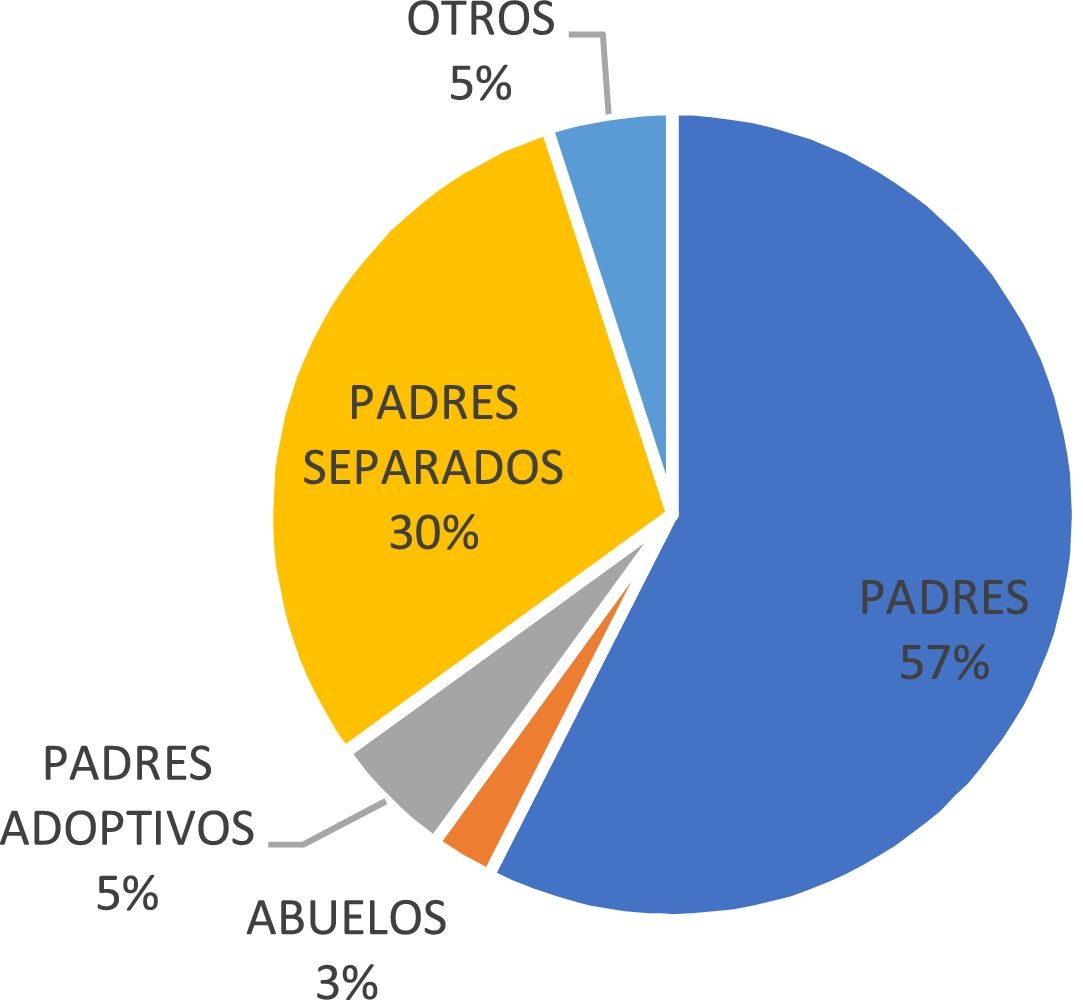

ResultsSociodemographic characteristicsA total of 40 patients was included. Of the total number of eligible patients (n=40), 37 (92%) were female and 3 (8%) were male (ratio 8:1). The average age of patients was 16.6±1.9 years. With regards to family structure, it was found that 57% (n=23) of the patients lived with both their parents and 30% (n=12) lived with one of their parents (separated parents) (Fig. 1).

On evaluating the level of education at the time of the study, it was found that 58% (n=23) of the population was in secondary school, 40% (n=16) was at university and 2% (n=1) was at primary school. In the academic performance analysis, 72% (n=29) of the population had excellent academic performance, 25% (n=10) had good performance and 3% (n=1) had regular performance. It was found that 85% (n=17) of the patients diagnosed with AN had excellent academic performance.

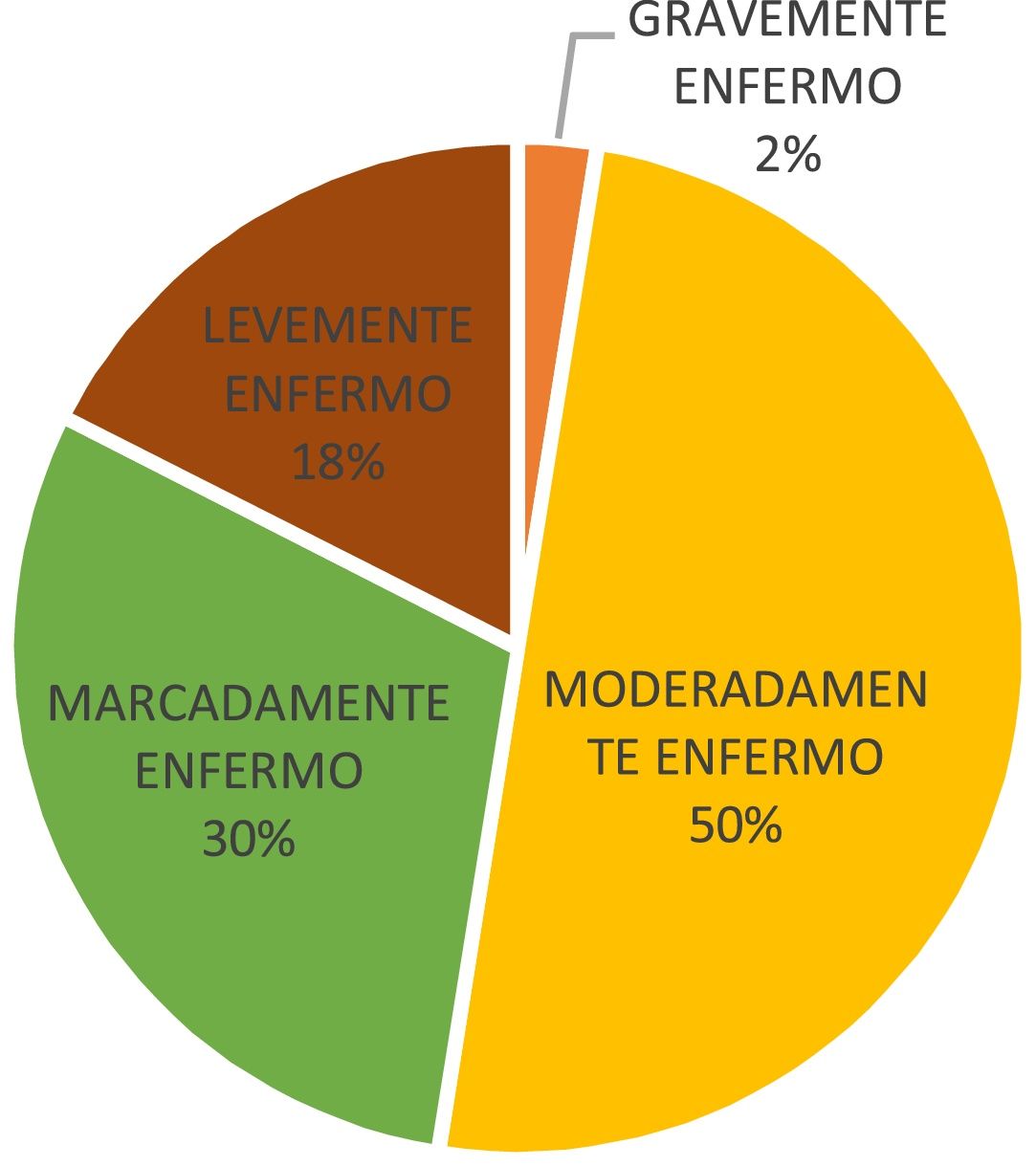

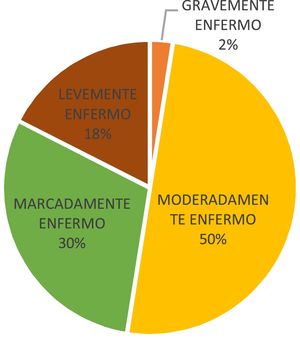

Eating disorderFifty percent (50%) (n=20) of the population had a diagnosis of AN, 37% (n=15) had BN, 8% (n=3) had eating disorder not otherwise specified and 5% (n=2) had binge-eating disorder. Regarding time since diagnosis of the eating disorder, a mean of 21 (6–63) months was found. On evaluating the severity of the disease, measured by the CGI (Clinical Global Impression) scale, 50% (n=20) of the participants were moderately ill, 30% (n=12) were markedly ill and only 2% were severely ill (Fig. 2).

Patients with AN were between the marked and moderate disease bands, with rates of 58.3% (n=7) and 50% (n=10), respectively. On determining BMI, a mean of 21.2 (14.5–19.2) was found, with a mean of 18.7 for AN and 22.9 for BN.

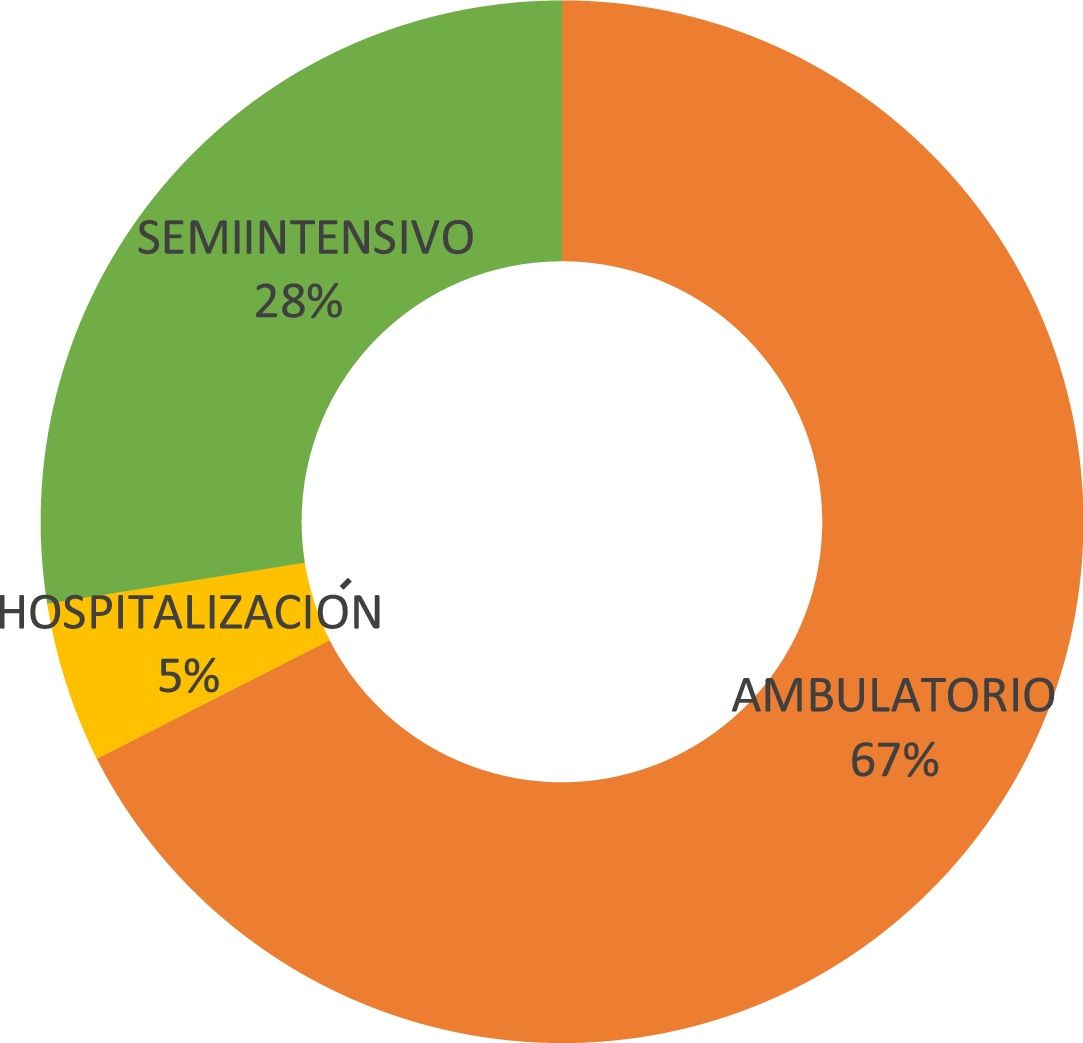

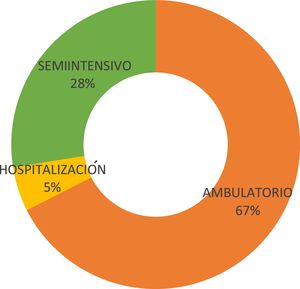

Treatment modality and historyMost of the patients (67% [n=27)] were receiving outpatient treatment at the time of the interview (Fig. 3).

The drug treatment being used by patients at the time of the study was selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in 60% (n=25), no drug treatment in 32% (n=12), dual-action antidepressants in 5% (n=2) and atypical antipsychotics in 3% (n=1).

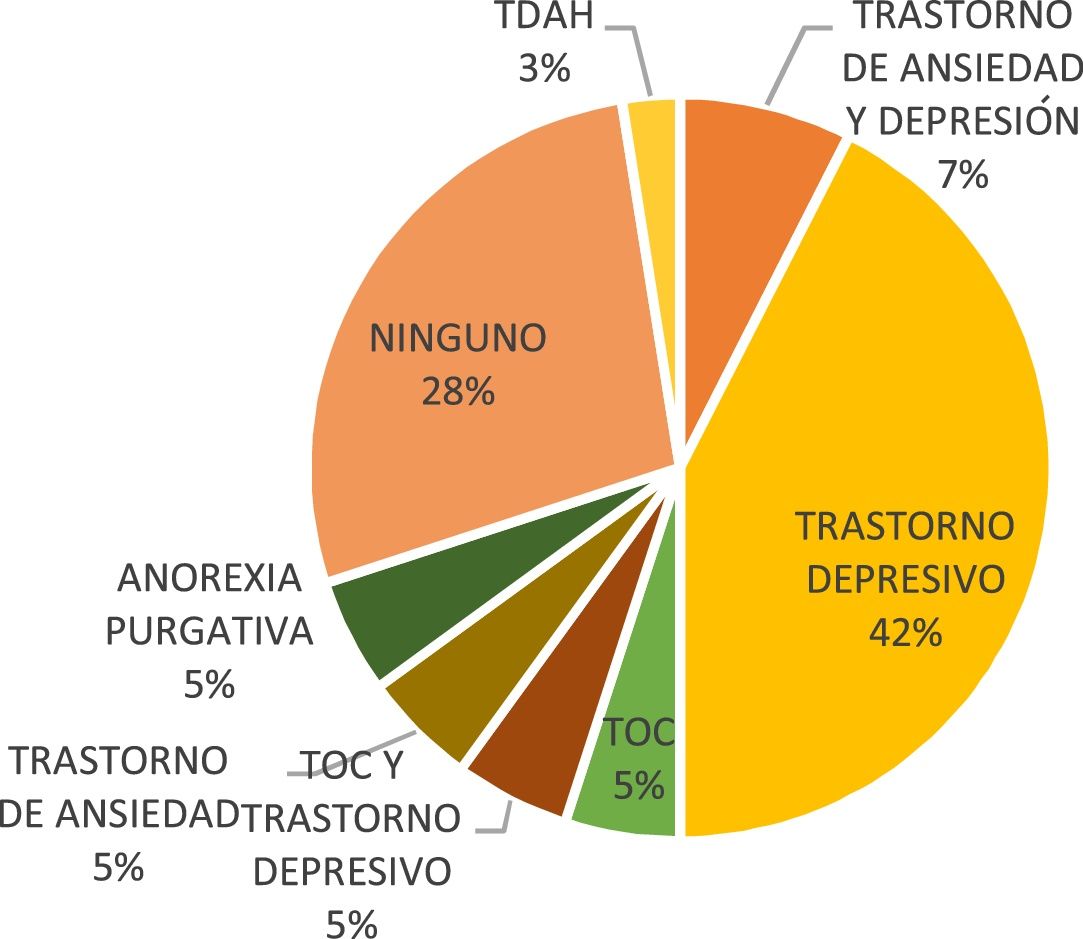

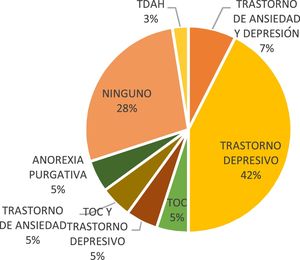

With regards to psychiatric history that did not form part of the comorbidity at the time of interview, 42% (n=17) had a history of depressive disorder (Fig. 4).

YSR questionnaireFor the anxiety dimension, 65% (n=26) of the patients with eating disorder met clinical criteria, 13% (n=5) were at clinical risk and 22% (n=9) were in the normal range. Of those patients who met anxiety criteria, 65% (n=13) had been diagnosed with AN and 73.3% (n=11) with BN. For the depression/withdrawal dimension, 30% (n=12) of the patients with eating disorder met clinical criteria for depression, 25% (n=10) were at clinical risk and 45% (n=18) were in the normal range. Of those who met clinical criteria for depression, 53.3% (n=8) had been diagnosed with BN and 20% (n=4) with AN.

For the somatic complaints dimension (tiredness, nightmares, nausea, headache, skin problems, abdominal pain and general pain), 9 patients with eating disorder (22.5%) were in the clinical range, 16 (40%) were at clinical risk and 15 (37.5%) were in the normal range. In total, 33.3% (n=5) of the patients who met clinical criteria had BN. For the social relations problems dimension, 7 patients with eating disorder (17.5%) had social problems and 26 (65%) did not. Twenty percent (20% [n=4]) of the patients with social relations problems had been diagnosed with AN and 20% (n=3) with BN.

For the thought problems dimension (evaluating such aspects as suicidal thoughts, repetitive or strange ideas, auditory and visual hallucinations or sleep disturbance), 32.5% (n=13) of the patients with eating disorder were in the clinical range and 55% (n=22) were in the normal range. Of these, 40% (n=8) had been diagnosed with AN.

For the attention problems dimension, a total of 5 patients with eating disorder (12.5%) met clinical criteria, 2 (5%) were at clinical risk and 33 (82.5%) were in the normal range. Of those patients who met clinical criteria, 20% (n=3) had been diagnosed with BN. For the aggression problems dimension (frequent arguments, hostility, disobedience, frequent mood swings, irritability, problems at school and at home or destruction of objects, among other things), 9 patients with eating disorder (22.5%) met clinical criteria and 26 (65%) were in the normal range. Of those patients who met clinical criteria for aggression, 25% (n=5) had been diagnosed with anorexia.

For the delinquent behaviour dimension (psychoactive substance use, alcohol and cigarette use, frequent lying, cheating, burglary, running away from home or school or starting fires, among other things), 7 patients diagnosed with an eating disorder (17.5%) met clinical criteria, 26 (45%) were in the normal range and 7 (17.5%) were at risk. Of those patients who met clinical criteria for delinquent behaviour, 20% (n=3) had been diagnosed with bulimia.

On evaluating internalising symptoms, 72.5% of the patients with eating disorder met clinical criteria and 20% were in the normal range. Eighty percent (80%) of the patients who met criteria for internalising symptoms had been diagnosed with BN and 75% with AN.

Regarding externalising symptoms, 42.5% of the patients with eating disorder were in the clinical range, 22.5%, were at clinical risk and 35% were in the normal range. Of those patients who met clinical criteria, 46.6% had been diagnosed with BN and 40% with AN.

The mean total score of the YSR questionnaire was 82.5 (15–143) points (clinical range). Overall, 62.5% (n=25) of the patients with eating disorder had scores within the clinical range, which was related to the severity of the eating disorder symptoms. Of those patients whose scores were within the clinical range, 73.3% (n=11) had been diagnosed with BN and 60% (n=11) with AN.

In total, 83.3% (n=10) of the patients who scored within the clinical range for eating disorder, according to the Clinical Global Impression scale of the YSR questionnaire, were markedly ill and 65% (n=13) were moderately ill.

DiscussionUsing the data obtained, a descriptive analysis was performed on the characteristics of a clinical population (n=40) diagnosed with eating disorder that was receiving interdisciplinary treatment (nutrition, psychology and psychiatry).

The distribution of patients by gender has a female:male ratio of 9:1, which is consistent with studies conducted in other countries, where eating disorders affect more females than males.7,8 With regards to family structure, 57% of the patients lived in two-parent homes, 30% in one-parent homes and 5% with adoptive parents, which is consistent with the national average. According to the Demography and Health Survey, one-third of all households in the country (33.2%) are two-parent households and 12.6% are single-parent households.9

On evaluating the level of education, all respondents were in education at the time of the interview, with 58% in secondary school, 40% at university and 2% at primary school, which is consistent with the patients’ ages. According to national education access rates, in Bogotá, 20.9% of females complete secondary education and 31.9% have access to further education. The rate of access is much higher depending on the socioeconomic characteristics of households,9 which is consistent with the findings of this study, given that the study population has access to pre-paid medicine and generally has a middle-high and high socioeconomic status. Regarding academic performance, 85% of the study population diagnosed with AN had excellent academic performance, which may be related to attitudes of perfectionism and self-demand, common characteristics of patients with these disorders.10 Several studies have described generally high intellectual function in patients with AN.11,12 Other authors have reported an average intellectual function in patients with AN, measured both in clinical groups13,14 and in population-based studies.15 However, one study found that patients with restrictive AN and a very low BMI (12.8) showed significantly reduced full-scale intelligence scores.16 Recent clinical studies and meta-analyses on neurocognitive functioning in eating disorders, specifically AN, show a mild to moderate effect on executive functioning compared to the general population, with changes in areas such as processing speed, working memory, visuospatial function, difficulties with inhibition and task switching.17–20

Regarding distribution by diagnosis, 50% of patients had AN, 37% had BN, 8% had an eating disorder not otherwise specified and 5% had binge-eating disorder. These findings are inconsistent with the figures described in the literature, where the highest prevalence estimates are for binge-eating disorder (1.6%–3.5%) followed by BN (0.9%–1.5%) and then AN (0.3%–0.9%).7,8 With regard to our results, it can be deduced that the high rate of AN and the low rate of binge-eating disorder may be due to the specialised paediatric institution for eating disorders, where highly complex cases with higher morbidity rates are treated, which in this case correspond to more serious conditions such as AN and BN.

On evaluating disease severity, as measured by the CGI scale, most of the patients interviewed were in the moderate-marked illness band, with the highest rates being for AN. A total of 58.3% had marked illness and 50% had moderate illness, which matches the degree of functional impairment and the semi-intensive, outpatient treatment modality, since the patients in the study were treated at a highly specialised eating disorder facility and therefore had a severe eating disorder.

With regards to the drug treatment received at the time of the interview, 60% were taking SSRIs, with fluoxetine being the most common. This is currently the most widely prescribed drug treatment. It has moderate scientific evidence for relapse prevention and the treatment of symptoms associated with psychiatric comorbidity (obsessive-compulsive disorder, depressive disorder, anxiety disorder) in patients with recovered nutritional status.21

Considering psychiatric history that does not form part of the current comorbidity, depressive disorder was found in 42% of the patients and no prior disorder was found in 28%. This has been described in several studies, in which depressive symptoms are a predictor of the subsequent onset of an eating disorder, and its incidence increases over the course of the disorder.8,22,23

On analysing the data obtained from the YSR questionnaire, in the anxiety dimension it was found that 65% of the patients with eating disorder met clinical criteria for diagnosing anxiety. A total of 73.3% of these had a diagnosis of BN, while 65% had a diagnosis of AN. This finding is consistent with the results of a study conducted on the sample population of the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey Replication, administered to 2980 patients with eating disorder. The highest risk (OR=8.6; 95% CI, 3.4–21.6) was for anxiety disorder in patients with BN and there was no association with AN (OR=1.9; 95% CI, 0.9–4.1).8 However, some studies have been conducted in clinical populations that report a higher comorbidity of anxiety disorder in AN than in BN. Population-based studies22 indicate that anxiety symptoms and eating disorders are not related.

For the depression/withdrawal dimension, 30% of the patients with eating disorder met clinical criteria for depression. In total, 53.3% were patients diagnosed with BN and 20% had been diagnosed with AN, which matches the findings of other studies8 that established a higher risk (OR=4.3; 95% CI, 1.7–10.8) of depressive disorder in patients with BN and a lower risk in AN (OR=2.7; 95% CI, 1.3–5.7).

For the somatic complaints dimension (tiredness, nightmares, nausea, headache, skin problems, abdominal pain, general pain), 22.5% of the patients with eating disorder met clinical criteria and 33.3% of these had BN. These data are consistent with the findings from other studies, which report that outpatients with BN had significantly higher levels of somatic symptoms than patients with anorexia.34 The severity of somatic symptoms was high with both disorders. Furthermore, there is evidence of a close association between the severity of somatic symptoms and the presence of anxiety and depression.24,25

On evaluating the general category of internalising symptoms, 72.5% of the patients with eating disorder met clinical criteria. Some 80% of these had been diagnosed with BN and 75% with AN, which confirms that comorbidity with affective and anxiety disorders is more the rule than the exception among patients with eating disorder.

For the thought problems dimension (evaluating suicidal thoughts, repetitive or strange ideas, auditory and visual hallucinations or sleep disturbance, among other things), 32.5% of the patients with eating disorder were in the clinical range and 40% of these had been diagnosed with AN. From these findings, it can be said that thought problems are symptoms that accompany anxiety and affective disorders, which are common in these patients.

For the attention problems dimension, 12.5% of the patients with eating disorder met clinical criteria for attention problems and 3 of these patients had been diagnosed with BN. The limited number of attention symptoms coincides with the finding of excellent academic performance. Numerous studies have found that ADHD is more closely related to eating disorders with compulsive binge eating, such as BN and binge-eating disorder.8,26,27 One meta-analysis found that people with ADHD had a similar risk of developing AN (OR=4.28; 95% CI, 2.24–8.16) and binge-eating disorder (OR=4.13; 95% CI, 3.00–5.67) and a higher risk of developing BN (OR=5.71; 95% CI, 3.56–9.16).28 A study conducted with data from the U.S. National Comorbidity Survey Replication and the National Survey of American Life found that ADHD is strongly associated with BN and that the lifetime association with AN is not statistically significant.35

For the aggression problems dimension (frequent arguments, hostility, disobedience, frequent mood swings, irritability, problems at school and at home or destruction of objects, among other things), 22.5% of the patients with eating disorder met clinical criteria and 25% of these had a diagnosis of anorexia. Some studies report more aggressiveness, hostility and anger in patients with eating disorders.29,30 Aggressiveness may be mediated by multiple factors, such as personality traits, emotion dysregulation and poor impulse control, which are characteristics of these disorders, especially the bulimia spectrum.31 The aggressiveness observed in patients with anorexia and bulimia may also be a consequence of the eating disorder symptoms, i.e. the constant cycle of binge eating and restrictive behaviour that leads to abnormal serotonin concentrations.32,33 Depression, which is fairly common in eating disorders, may result in hostile behaviours and a higher propensity to aggression.29

For the delinquent behaviour dimension (psychoactive substance use, alcohol and cigarette use, frequent lying, cheating, burglary, running away from home or school or starting fires, among other things), 17.5% of the patients diagnosed with an eating disorder met clinical criteria and 20% of these had a diagnosis of BN. These findings are consistent with those from another study,8 which reported a higher risk of conduct disorders in patients with BN (OR=4.7; 95% CI, 2.0–10.8). This association increases with the addition of psychoactive substance use (OR=5.3; 95% CI, 1.6–17.6).

On evaluating the category of externalising symptoms, 42.5% of the patients with eating disorder were in the clinical range. Of those patients who met the criteria, 46.6% had a diagnosis of BN and 40% had a diagnosis of AN. It can therefore be said that patients with BN have more behavioural problems.

The mean total score of the YSR questionnaire was 82.5 (15–143) points (clinical range). Some 62.5% of the patients with eating disorder had scores within the clinical range, which is related to the severity of the eating disorder symptoms. Of these patients, 73.3% had a diagnosis of BN, which implies that this condition occurs in higher comorbidity with Axis I symptoms than the other eating disorders.

The high prevalence of internalising and externalising symptoms found in the study population, especially in patients diagnosed with BN, creates the need for strategies aimed at the early detection of affective and behavioural disorders when it comes to tackling eating disorders. The aim of this is not just to reduce the impact on eating disorder symptoms but to improve the general functioning of patients and their family environment.

LimitationsThe study has the following limitations: A higher frequency of the more severe conditions, such as AN, was observed because the study site was a specialised eating disorder clinic. Since the objective was to describe emotional and/or behavioural symptoms associated with eating disorders, a cross-sectional, descriptive, observational study was conducted and therefore the correlations found do not imply causality. The YSR questionnaire was used as the core instrument, and more in-depth assessments, such as personality inventories and tests, were not administered. With regards to sociodemographic characteristics, economic status was not included since all the study patients were from complementary healthcare plans.

ConclusionsThere is a higher prevalence of eating disorders in females. Associated symptoms have a huge impact on the quality of life of patients and their families.

Most patients with eating disorders have excellent academic performance, which may make early detection of the condition difficult since it does not alter their functioning, even at more advanced stages of the disease.

Half of the patients enrolled in this study had a clinical diagnosis of AN, which is contrary to global prevalence rates, suggesting that this disorder generates a more visible psychopathology and morbidity, resulting in a greater number of appointments and the search for more specialised care.

The most prevalent psychiatric history in adolescents with eating disorders was major depressive disorder. YSR scores within the clinical range for anxiety and depression occurred more frequently in patients with BN.

Comorbidity with affective and anxiety spectrum disorders are the norm for patients with eating disorders, which makes it necessary to actively look for these conditions in order to guarantee early and timely detection during treatment.

Externalising symptoms (problems of aggressiveness, delinquent behaviour) are fairly common among patients with eating disorders and this is more evident among patients with BN.

Patients with BN scored higher for emotional and behavioural symptoms than patients with other eating disorders. This suggests that BN requires more psychopathology, which should be carefully examined when providing health care in an attempt to reduce the functional impact that these symptoms have on an individual.

When treating eating disorders, strategies must be implemented that enable early detection of comorbidities in order to provide early treatment and reduce any negative impact on the patient and his/her family, resulting in less severe eating disorder symptoms.

In Colombia, clinical studies must be conducted in young patients with eating disorders from all socioeconomic strata in order to obtain a broader understanding of the behaviour of these disorders.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.