Bipolar disorder (BD) is a serious mental illness with a chronic course and significant morbidity and mortality. BD has a lifetime prevalence rate of 1%–1.5% and is characterised by recurrent episodes of mania and depression, or a mixture of both phases. Although it has harmacological and psychotherapeutic treatment, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has shown beneficial effects, but there is not enough clinical information in the current literature.

MethodsThe main aim was to determine the efficacy of CBT alone or as an adjunct to pharmacological treatment for BD. A systematic review of 17 articles was carried out. The inclusion criteria were: quantitative or qualitative research aimed at examining the efficacy of CBT in BD patients with/without medication; publications in English language; and) being 18–65 years of age. The exclusion criteria were: review and meta-analysis articles; articles that included patients with other diagnoses in addition to BD and that did not separate the results based on such diagnoses; and studies with patients who did not meet the DSM or ICD criteria for BD. The PubMed, PsycINFO and Web of Science databases were searched up to 5 January 2020. The search strategy was: “Bipolar Disorder” AND “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy”.

ResultsA total of 1531 patients both sexes were included. The weighted mean age was 40.703 years. The number of sessions ranged from 8 to 30, with a total duration of 45–120 min. All the studies show variable results in improving the level of depression and the severity of mania, improving functionality, reducing relapses and recurrences, and reducing anxiety levels and the severity of insomnia.

ConclusionsThe use of CBT alone or adjunctive therapy in BD patients is considered to show promising results after treatment and during follow-up. Benefits include reduced levels of depression and mania, fewer relapses and recurrences, and higher levels of psychosocial functioning. More studies are needed.

El trastorno bipolar (TB) es una enfermedad mental grave con un curso crónico y una morbimortalidad importante. El TB tiene una tasa de prevalencia a lo largo de la vida del 1 al 1,5% y se caracteriza por episodios recurrentes de manía, depresión o una mezcla de ambas fases. Aunque tiene tratamiento farmacológico y psicoterapéutico, la terapia cognitiva conductual (TCC) ha mostrado efectos beneficiosos, pero no se cuenta con suficiente información clínica en la literatura actual.

MétodosEl objetivo principal es determinar la eficacia de la TCC sola o como complemento del tratamiento farmacológico para el TB. Se realizó una revisión sistemática de 17 artículos. Los criterios de inclusión fueron: investigación cuantitativa o cualitativa dirigida a examinar la eficacia de la TCC en pacientes con TB con/sin medicación, publicaciones en idioma inglés y tener 18–65 años de edad. Los criterios de exclusión fueron: artículos de revisión y metanálisis, artículos que incluían a pacientes con otros diagnósticos además de TB y no separaban los resultados basados en dichos diagnósticos y estudios con pacientes que no cumplían los criterios de TB del DSM o ICD. Se realizaron búsquedas en las bases de datos PubMed, PsycINFO y Web of Science hasta el 5 de enero de 2020. La estrategia de búsqueda fue: “Bipolar Disorder” AND “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy”.

ResultadosSe incluyó en total a 1.531 pacientes de ambos sexos. La media de edad ponderada fue 40,703 años. El número de sesiones varió de 8 a 30, con una duración total de 45–120 min. Todos los estudios muestran resultados variables en la mejora del nivel de depresión y la gravedad de la manía, mejora de la funcionalidad, disminución de recaídas y recurrencias, reducción de los niveles de ansiedad y reducción de la gravedad del insomnio.

ConclusionesSe considera que la TCC sola o complementaria para pacientes con TB muestra resultados prometedores después del tratamiento y durante el seguimiento. Los beneficios incluyen niveles reducidos de depresión y manía, menos recaídas y recurrencias y niveles más altos de funcionamiento psicosocial. Se necesitan más estudios.

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a severe mental illness with a chronic course and significant morbidity and mortality rates. BD has a lifetime prevalence rate of 1%–1.5% and is characterised by recurrent episodes of mania, depression, or a mixture of the two phases.1,2 BD causes cognitive symptoms, functional impairment and poor physical health and is associated with a high rate of suicidal behaviour. These patients have difficulties with interpersonal relationships due to the dramatic alternation of manic, hypomanic and depressive mood cycles.3–5

A cohort study with a large sample size (n = 1469) showed that 58% of patients with BD types I and II recovered, but approximately half of them suffered a recurrence within two years.6 This severe mood disorder affects Millions of patients worldwide, costing thousands of dollars for years of living with a disability.7

It has been proven that there is a consistent biological basis in the development of the disease, which is why psychotropic drugs are the first-line treatment. However, a growing body of literature indicates that combined drug therapy and psychotherapy are more effective in treating patients with BD than medication alone.8

As an adjuvant treatment, psychotherapy helps patients with BD improve treatment adherence, illness awareness and coping skills for problematic life events, collectively resulting in a better response to psychotropic medications. Among the psychosocial therapies that are potential adjuncts to medications for patients with BD, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a promising treatment option. However, it has inconclusive findings due to the lack of large study samples and their heterogeneity.9

Randomised controlled trials (RCT) published in the last 10 years have revealed the potential benefits of CBT as an adjunct to mood stabilisers for preventing relapse, alleviating symptoms and improving medication adherence.10 Some meta-analyses have recently evaluated the effectiveness of CBT for BD. These studies have shown that CBT has a negligible impact on clinical symptoms, but the evidence remains limited.11,12

In this study, we analysed research on the effectiveness of CBT alone or adjuvant to medications for the treatment of BD to guide mental health professionals in making evidence-based decisions for treating these patients.

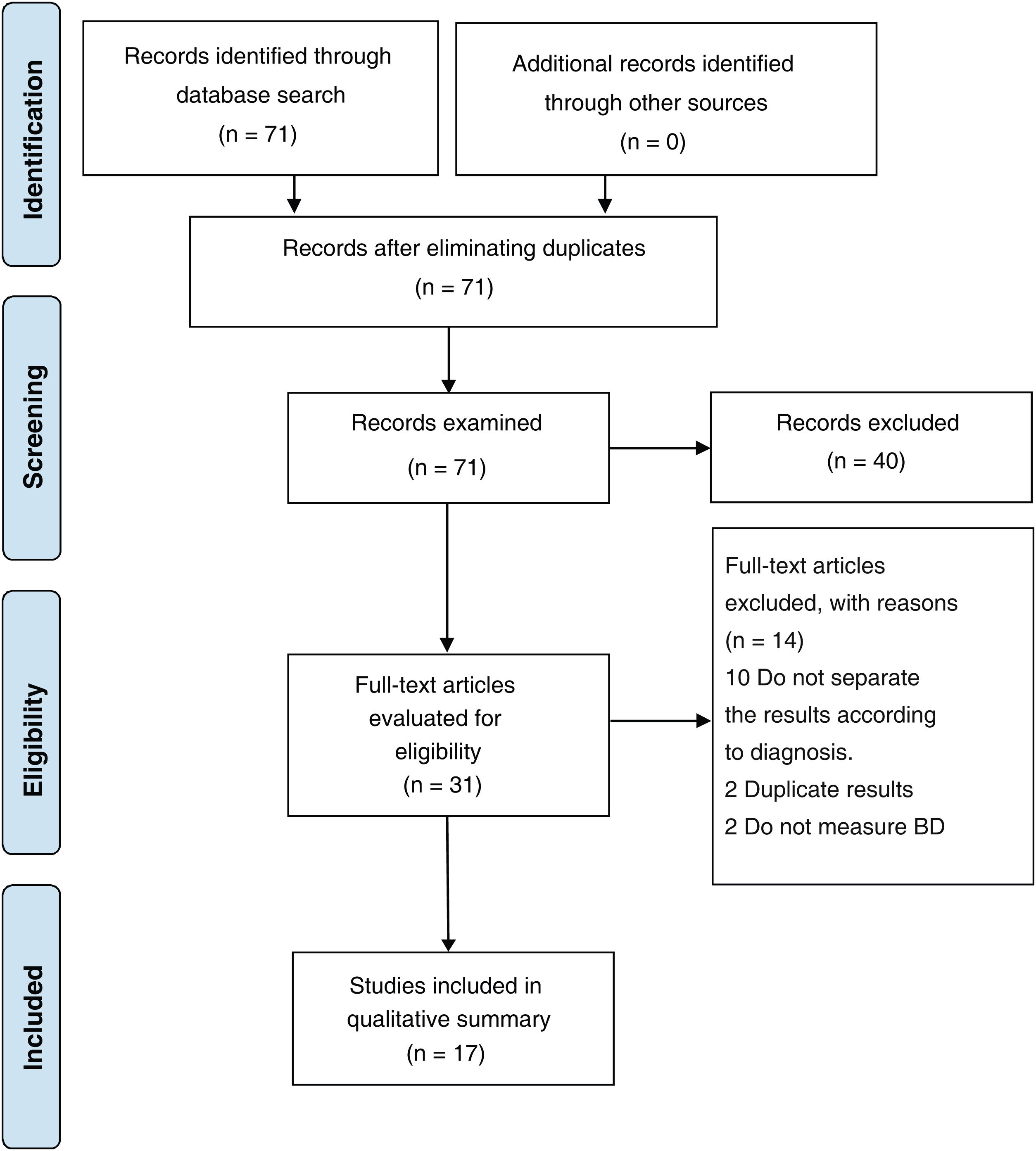

MethodsTo achieve the objectives of this review, we followed the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) model by Moher et al.13

Selection criteria for studiesThe inclusion criteria for the studies were: quantitative or qualitative research aimed at examining the effectiveness of CBT in patients with BD with or without medication, publications in English, and ages between 18 and 65. The exclusion criteria were: review and meta-analysis articles, articles that included patients with diagnoses other than BD that did not separate the results based on such diagnoses, and studies with patients who did not meet the DSM or ICD criteria for BD.

Search strategySearches were made in the PubMed, PsycINFO, and Web of Science databases up to 5 January 2020. The search strategy used in each of these databases was as follows: “Bipolar Disorder” AND “Cognitive Behavioral Therapy”. The filters applied in the three databases allowed the inclusion criteria to be met.

Study selection processThis process was carried out in four phases. First (article identification phase), the results of the searches in the three databases were unified and duplicate articles were eliminated. Second (screening phase), we read the titles and abstracts of the articles that potentially met the inclusion criteria. If there were doubts, we reviewed the full text of the questioned article. Third (eligibility phase), the full-text articles preselected in the previous phase and the questioned articles were examined and read independently. Finally (inclusion phase), we decided to select the articles included in this systematic review.

Data extraction process for each studyThe following information was extracted from the selected articles: study title; author(s) and year of publication; size of the patient sample; characteristics of the participants (sociodemographic data, diagnosis, whether they were outpatients or hospitalised and phase of the disease at the time of BD evaluation); study characteristics (methodology, duration and existence of a control group); type of treatment received by patients; characteristics of the intervention (number of sessions, duration of treatment, group size and professional certification); variables and measurement instruments; and results with mention of statistical significance. The results were classified into primary variables (depressive symptoms and mania), those that reflect the most critical symptoms which were expected in all the included studies, and secondary variables (functioning, relapses/recurrences, level of anxiety and insomnia), which were those associated with other clinical characteristics not considered in all the studies.

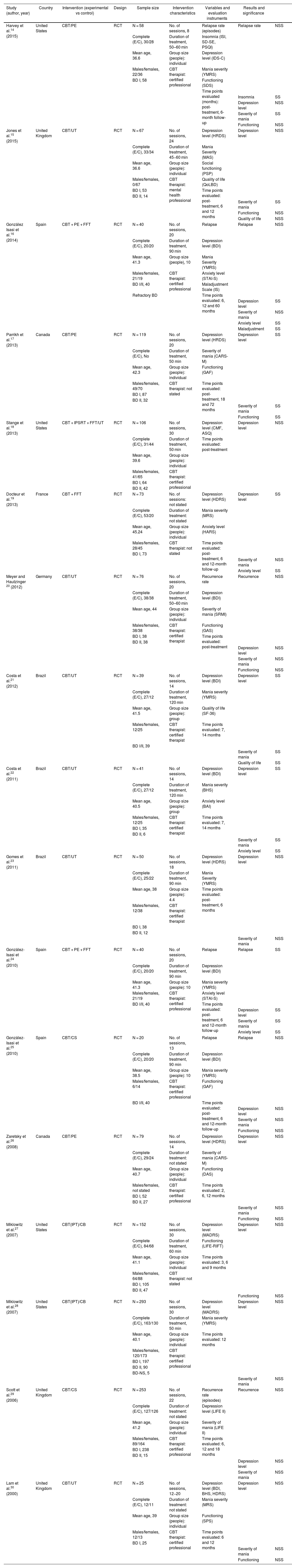

ResultsMain demographic characteristicsWe selected 17 original studies which met the inclusion criteria. Fig. 1 shows the selection process for these articles. Their main characteristics are set out in Table 1. The selected studies included a total of 1531 patients. All of them were outpatients. Based on the available data (17 articles), the weighted mean age of the patients was 40.703 years. We can see that the studies were carried out in seven different countries, distributed as follows: United States (4 studies); United Kingdom (3 studies); Spain (3 studies); Brazil (3 studies); Canada (2 studies); France (1 study); and Germany (1 study). All the studies included were randomised controlled trials (RCT). Most included single CBT interventions compared to a standard BD intervention control group. However, in five studies, CBT was an adjunct to other interventions such as psychoeducation (PE), family-focused therapy (FFT), and interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) and included as part of intensive psychosocial treatment (IPT) in two of these studies.

Characteristics of the studies selected.

| Study (author, year) | Country | Intervention (experimental vs control) | Design | Sample size | Intervention characteristics | Variables and evaluation instruments | Results and significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harvey et al.14 (2015) | United States | CBT/PE | RCT | N = 58 | No. of sessions, 8 | Relapse rate (episodes) | Relapse rate | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 30/28 | Duration of treatment, 50–60 min | Insomnia (ISI, SD-SE, PSQI) | ||||||

| Mean age, 36.6 | Group size (people): individual | Depression level (IDS-C) | ||||||

| Males/females, 22/36 | CBT therapist: certified professional | Mania severity (YMRS) | ||||||

| BD I, 58 | Functioning (SDS) | |||||||

| Time points evaluated (months): post-treatment, 6-month follow-up | ||||||||

| Insomnia | SS | |||||||

| Depression level | NSS | |||||||

| Severity of mania | SS | |||||||

| Functioning | NSS | |||||||

| Jones et al.15 (2015) | United Kingdom | CBT/UT | RCT | N = 67 | No. of sessions, 24 | Depression level (HRDS) | Depression level | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 33/34 | Duration of treatment, 45−60 min | Mania Severity (MAS) | ||||||

| Mean age, 36.6 | Group size (people): individual | Social functioning (PSP) | ||||||

| Males/females, 0/67 | CBT therapist: mental health professional | Quality of life (QoLBD) | ||||||

| BD I, 53 | Time points evaluated: post-treatment, 6 and 12 months | |||||||

| BD II, 14 | ||||||||

| Severity of mania | SS | |||||||

| Functioning | NSS | |||||||

| Quality of life | NSS | |||||||

| González Isasi et al.16 (2014) | Spain | CBT + PE + FFT | RCT | N = 40 | No. of sessions, 20 | Relapse | Relapse | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 20/20 | Duration of treatment, 90 min | Depression level (BDI) | ||||||

| Mean age, 41.3 | Group size (people), 10 | Mania Severity (YMRS) | ||||||

| Males/females, 21/19 | CBT therapist: certified professional | Anxiety level (STAI-S) | ||||||

| BD I/II, 40 | Maladjustment Scale (IS) | |||||||

| Refractory BD | Time points evaluated: 6, 12 and 60 months | |||||||

| Depression level | SS | |||||||

| Severity of mania | NSS | |||||||

| Anxiety level | SS | |||||||

| Maladjustment | SS | |||||||

| Parrikh et al.17 (2013) | Canada | CBT/PE | RCT | N = 119 | No. of sessions, 20 | Depression level (HRDS) | Depression level | SS |

| Complete (E/C), No | Duration of treatment, 50 min | Severity of mania (CARS-M) | ||||||

| Mean age, 42.3 | Group size (people): individual | Functioning (GAF) | ||||||

| Males/females, 49/70 | CBT therapist: not stated | Time points evaluated: post-treatment, 18 and 72 months | ||||||

| BD I, 87 | ||||||||

| BD II, 32 | ||||||||

| Severity of mania | SS | |||||||

| Functioning | SS | |||||||

| Stange et al.18 (2013) | United States | CBT + IPSRT + FFT/UT | RCT | N = 106 | No. of sessions, 30 | Depression level (CMF, ASQ) | Depression level | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 31/44 | Duration of treatment, 50 min | Time points evaluated: post-treatment | ||||||

| Mean age, 39.6 | Group size (people): individual | |||||||

| Males/females, 41/65 | CBT therapist: certified professional | |||||||

| BD I, 64 | ||||||||

| BD II, 42 | ||||||||

| Docteur et al.19 (2013) | France | CBT + FFT | RCT | N = 73 | No. of sessions: not stated | Depression level (HDRS) | Depression level | SS |

| Complete (E/C), 53/20 | Duration of treatment: not stated | Mania severity (MRS) | ||||||

| Mean age, 45.24 | Group size (people): individual | Anxiety level (HARS) | ||||||

| Males/females, 28/45 | CBT therapist: not stated | Time points evaluated: post-treatment, 6 and 12-month follow-up | ||||||

| BD I, 73 | ||||||||

| Severity of mania | NSS | |||||||

| Anxiety level | SS | |||||||

| Meyer and Hautzinger 20 (2012) | Germany | CBT/UT | RCT | N = 76 | No. of sessions, 20 | Recurrence rate | Recurrence | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 38/38 | Duration of treatment, 50–60 min | Depression level (BDI) | ||||||

| Mean age, 44 | Group size (people): individual | Severity of mania (SRMI) | ||||||

| Males/females, 38/38 | CBT therapist: certified therapist | Functioning (GAS) | ||||||

| BD I, 38 | Time points evaluated: post-treatment | |||||||

| BD II, 38 | ||||||||

| Depression level | NSS | |||||||

| Severity of mania | NSS | |||||||

| Functioning | NSS | |||||||

| Costa et al.21 (2012) | Brazil | CBT/UT | RCT | N = 39 | No. of sessions, 14 | Depression level (BDI) | Depression level | SS |

| Complete (E/C), 27/12 | Duration of treatment, 120 min | Mania severity (YMRS) | ||||||

| Mean age, 41.5 | Group size (people): group | Quality of life (SF-36) | ||||||

| Males/females, 12/25 | CBT therapist: certified therapist | Time points evaluated: 7, 14 months | ||||||

| BD I/II, 39 | ||||||||

| Severity of mania | SS | |||||||

| Quality of life | SS | |||||||

| Costa et al.22 (2011) | Brazil | CBT/UT | RCT | N = 41 | No. of sessions, 14 | Depression level (BDI) | Depression level | SS |

| Complete (E/C), 27/12 | Duration of treatment, 120 min | Mania severity (BHS) | ||||||

| Mean age, 40.5 | Group size (people): group | Anxiety level (BAI) | ||||||

| Males/females, 12/25 | CBT therapist: certified therapist | Time points evaluated: 7, 14 months | ||||||

| BD I, 35 | ||||||||

| BD II, 6 | ||||||||

| Severity of mania | SS | |||||||

| Anxiety level | SS | |||||||

| Gomes et al.23 (2011) | Brazil | CBT/UT | RCT | N = 50 | No. of sessions, 18 | Depression level (HDRS) | Depression level | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 25/22 | Duration of treatment, 90 min | Mania Severity (YMRS) | ||||||

| Mean age, 38 | Group size (people): 4.4 | Time points evaluated: post-treatment, 6 months | ||||||

| Males/females, 12/38 | CBT therapist: certified therapist | |||||||

| BD I, 38 | ||||||||

| BD II, 12 | ||||||||

| Severity of mania | NSS | |||||||

| González-Isasi et al.24 (2010) | Spain | CBT + PE + FFT | RCT | N = 40 | No. of sessions, 20 | Relapse | Relapse | SS |

| Complete (E/C), 20/20 | Duration of treatment, 90 min | Depression level (BDI) | ||||||

| Mean age, 41.3 | Group size (people): 10 | Mania severity (YMRS) | ||||||

| Males/females, 21/19 | CBT therapist: certified professional | Anxiety level (STAI-S) | ||||||

| BD I/II, 40 | Time points evaluated: post-treatment, 6 and 12-month follow-up | |||||||

| Depression level | SS | |||||||

| Severity of mania | SS | |||||||

| Anxiety level | SS | |||||||

| González-Isasi et al.25 (2010) | Spain | CBT/CS | RCT | N = 20 | No. of sessions, 13 | Relapse | Relapse | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 20/20 | Duration of treatment, 90 min | Depression level (BDI) | ||||||

| Mean age, 38.5 | Group size (people): 10 | Mania severity (YMRS) | ||||||

| Males/females, 6/14 | CBT therapist: certified professional | Functioning (GAF) | ||||||

| BD I/II, 40 | Time points evaluated: post-treatment, 6 and 12-month follow-up | |||||||

| Depression level | NSS | |||||||

| Severity of mania | NSS | |||||||

| Functioning | NSS | |||||||

| Zaretsky et al.26 (2008) | Canada | CBT/PE | RCT | N = 79 | No. of sessions, 14 | Depression level (HDRS) | Depression level | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 29/24 | Duration of treatment: not stated | Severity of mania (CARS-M) | ||||||

| Mean age, 40.7 | Group size (people): individual | Functioning (DAS) | ||||||

| Males/females, not stated | CBT therapist: certified professional | Time points evaluated: 2, 6, 12 months | ||||||

| BD I, 52 | ||||||||

| BD II, 27 | ||||||||

| Severity of mania | NSS | |||||||

| Functioning | NSS | |||||||

| Miklowitz et al.27 (2007) | United States | CBT(IPT)/CB | RCT | N = 152 | No. of sessions, 30 | Depression level (MADRS) | Depression level | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 84/68 | Duration of treatment, 60 min | Functioning (LIFE-RIFT) | ||||||

| Mean age, 41.1 | Group size (people): individual | Time points evaluated: 3, 6 and 9 months | ||||||

| Males/females, 64/88 | CBT therapist: not stated | |||||||

| BD I, 105 | ||||||||

| BD II, 47 | ||||||||

| Functioning | NSS | |||||||

| Miklowitz et al.28 (2007) | United States | CBT(IPT)/CB | RCT | N = 293 | No. of sessions, 30 | Depression level (MADRS) | Depression level | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 163/130 | Duration of treatment, 50 min | Mania severity (YMRS) | ||||||

| Mean age, 40.1 | Group size (people): individual | Time points evaluated: 12 months | ||||||

| Males/females, 120/173 | CBT therapist: certified professional | |||||||

| BD I, 197 | ||||||||

| BD II, 90 | ||||||||

| BD-NS, 5 | ||||||||

| Severity of mania | NSS | |||||||

| Scott et al.29 (2006) | United Kingdom | CBT/CS | RCT | N = 253 | No. of sessions, 22 | Recurrence rate (episodes) | Recurrence | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 127/126 | Duration of treatment: not stated | Depression level (LIFE II) | ||||||

| Mean age, 41.2 | Group size (people): individual | Severity of mania (LIFE II) | ||||||

| Males/females, 89/164 | CBT therapist: certified professional | Time points evaluated: 6, 12 and 18 months | ||||||

| BD I, 238 | ||||||||

| BD II, 15 | ||||||||

| Depression level | NSS | |||||||

| Severity of mania | NSS | |||||||

| Lam et al.30 (2000) | United Kingdom | CBT/UT | RCT | N = 25 | No. of sessions, 12−20 | Depression level (BDI, BHS, HDRS) | Depression level | NSS |

| Complete (E/C), 12/11 | Duration of treatment: not stated | Mania severity (MRS) | ||||||

| Mean age, 39 | Group size (people): individual | Functioning (SPS) | ||||||

| Males/females, 12/13 | CBT therapist: certified professional | Time points evaluated: 6 and 12 months | ||||||

| BD I, 25 | ||||||||

| Severity of mania | NSS | |||||||

| Functioning | NSS |

ASQ: attributional style questionnaire; BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; BDI: Beck’s Depression Index; BHS: Beck Hopelessness Scale; CARS-M: clinician-administered rating scale for mania; CBT: cognitive-behavioural therapy; CMF: clinical monitoring form; DAS: dysfunctional attitude scale; FFT: family-focused treatment; GAF: global assessment of functioning; GAS: global assessment scale; HARS: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; HRSD: Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; IDS-C: inventory of depressive symptomatology, clinician rating; IPSRT: interpersonal and social rhythm therapy; IS: maladjustment scale; ISI: insomnia severity index; LIFE II: longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation; LIFE-RIFT: longitudinal interval follow-up evaluation–range of impaired functioning tool; MAS: Bech–Rafaelsen Mania Scale; NS: not specified; NS: not significant; PE: psychoeducation; PSP: personal and social functioning scale; PSQI: Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; QoL BD: brief quality of life in bipolar disorder questionnaire; RCT: randomised clinical trial; SDS: Sheehan Disability Scale; SD-SE: sleep daily sleep efficiency; SS: statistical significance; SRMI: self rating mania inventory; STAI-S: state trait anxiety inventory; UT: usual treatment; YMRS: Young Mania Rating Scale.

The diagnoses of BD I and BD II were considered in 14 studies, while three only included patients with BD I.

In 12 studies, female patients outnumbered male patients, with males predominating in only two; in one, the gender distribution was equal, and in another, it was unclear because it was not detailed in the article’s content.

Regarding the intervention, the number of sessions varied from 8 to 30, with a total duration of 45–120 min. In 11 studies, CBT was performed in individual mode, while in six, it was in group mode. In all 17 studies, a certified professional carried out the single and adjunctive CBT interventions.

Primary variablesDepressive symptoms and maniaIn 15 of the studies, the level of depression and severity of mania were assessed; in 2, only the level of depression was assessed (Stange, 2013; Miklowitz, 2007). With regard to the effectiveness in the CBT groups, all studies show improvements in the scores of the instruments applied for level of depression and severity of mania, but nine of the 17 studies did not show statistical significance in the clinical assessment after the treatment. In four of the 17 studies, statistical significance was shown in both variables (Parrikh, 2013; Costa, 2012; Costa, 2011; Gonzalez-Isasi, 2010). In two of the 17, partial significance was shown, in one for mania but not for depression and in the other, vice versa.

Secondary variablesFunctioningIn eight studies, functioning was seen to improve (Harvey, 2015; Jones, 2015; Parrikh, 2013; Meyer, 2012; Gonzalez-Isasi, 2010; Zaretsky, 2008; Miklowitz, 2007; Lam, 2000). However, that improvement was only statistically significant in one (Parrikh, 2013). Many of these studies also measured quality of life and maladjustment, so it is specified that the assessment of these variables is different from functioning. The instruments used to assess functioning were varied: DAS, PSP, GAF, SDS, GAS and LIFE-RIFT.

Relapses and recurrencesSix of the 17 studies (Harvey, 2015; Gonzalez-Isasi, 2014; Meyer, 2012; Gonzalez-Isasi, 2010; Gonzalez-Isasi, 2010; Scott, 2006) evaluated the relapse/recurrence rates, measured in several hospitalisations or clinical worsening, in which there was a decrease in these values. However, only one showed statistical significance (Gonzales-Isasi, 2010). In three studies, relapse was considered as clinical worsening during the episode of illness and follow-up according to the established time points. In contrast, recurrences during follow-up were considered when significant clinical improvement had already been achieved, and clinical decline led to hospitalisation. The measurement of this variable was objective and tangible, quantified as episodes, so it did not require longitudinal psychometric scores, which explains why all authors do not share this criterion.

Anxiety levelIn four of the studies, CBT, compared to the usual treatment, achieved a statistically significant reduction in anxiety levels when applying the STAI-S, HARS and BAI instruments (Gonzalez-Isasi, 2014; Docteur, 2013; Costa, 2011; Gonzalez-Isasi, 2010). The instruments are varied. Neither the predominant affective phase of the patients nor whether it was BD I or II was specified. This is important, as anxiety occurs with much greater intensity in manic states and subsyndromal states.

InsomniaOnly in one study (Harvey, 2015) in which CBT and PE were compared significant reductions in insomnia severity were achieved six months after treatment using the ISI, SD-SE and PSQI instruments. Although insomnia was measured in only one study with different instruments, significant differences were obtained with the treatment of BD⠀I, coinciding with improvement in I, coinciding with improvement in the levels of depression, anxiety and mania. The predominant condition of the patients at the time of measurement was not specified; this would be important, as insomnia is considered a cardinal symptom of mania/hypomania and depression levels are measured simultaneously.

DiscussionIn this review, we analysed 17 RCTs, which compared treatment results using CBT alone or adjuvant to drug therapy to usual treatment for patients diagnosed with BD. Primary variables were assessed, such as relapse/recurrence, level of depression, severity of mania, level of anxiety, insomnia and functioning. The role of antidepressants in influencing effectiveness outcomes has not been clearly determined.

CBT positively influenced the outcomes in terms of levels of depression and mania considered in 15 studies in our review. Out of all of them, despite the improvements in the scores, the clinical improvement in BD I and II was only statistically significant in six. These findings are consistent with those of Chiang.31 Despite including studies of the application of CBT alone and adjuvant to other treatments for BD, the meta-analysis indicates a mild-to-moderate effect size in reducing the rate of relapses and manic-depressive symptoms, especially in patients with BD I. The assessment instruments were varied, which reduces the clarity of the outcome but is helpful to compare our findings. In their systematic review, Oud et al.33 report that CBT reduces depressive and manic symptoms, hospital readmissions and relapses, which is also in line with our study. In contrast, Chatterton et al.32 conclude that neither CBT alone nor combined with PE generate significant reductions in depressive symptoms in any of their studies despite measuring scale scores at different post-treatment time points. However, PE alone, combined with CBT, showed a significant reduction in manic symptoms associated with lack of adherence to treatment and lower relative risk. Across the 12 studies of PE by Chatterton et al., the variables studied are limited and different, so there needs to be more clarity as to why the results differ from those of CBT. These authors finally point out that the combination of both treatments offers better overall results, as does da Costa et al.,34 who include in their findings a better quality of life, as well as a reduction in depressive and manic symptoms. Ye et al.11 show that CBT significantly reduces the severity of manic symptoms and relapses, but not depressive symptoms, at different measurement time points.

Functioning, as a secondary variable, shows clinical improvement with CBT but is not statistically significant in all studies. As in the other variables, the psychometric instruments were different, and the operationalisation given to functioning is confusing, as this could be considered the quality of life and maladjustment, so we have attempted to separate and avoid biases in the analysis. Our study’s improvement in functioning scores coincided with the levels of depression and severity of mania in BD I and BD II. These findings are compatible with Chatterton et al., who consider that the coinciding of improvement in mania and global functioning with CBT alone and in combination indicates increasing effectiveness over time, with more benefits in patients with BD I.

The level of anxiety and insomnia were variables little studied. They much less discussed in previous systematic reviews, as the results reflect significant reductions in mania, depression, number of relapses and functioning. This is likely because few reviews and meta-analyses include studies based on secondary variables, and anxiety and insomnia are considered to underlie measures of depression and anxiety. These differences are not discussed in other studies.

The limitations lie in the heterogeneity of the sample participants in the included studies and the small number of studies carried out to date that only compare CBT with standard psychopharmacological treatment and the combination of the two. During the search for information, we found that other systematic reviews and meta-analyses include interventions that do not follow the basis of pure CBT, such as MBCT (Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy), CT (Cognitive Therapy) and PE, and the objectivity and quality of the study are lost, which biases our results. It is necessary to expand the number of RCT with a greater number of participants.

ConclusionsCBT alone or as an adjunct for BD patients shows promising results after treatment and during follow-up. Benefits include reduced levels of depression and mania, fewer relapses and recurrences, and increased levels of psychosocial functioning. Additional studies should investigate optimal patient selection strategies to maximise the benefits of CBT as an adjunct.

FundingThe author declares self-financing.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Special thanks for advising on this study to Dr Nelson Andrade of the Alcalá de Henares University, Madrid, Spain.