Since the emergence of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), the world has faced a pandemic with consequences at all levels. In many countries, the health systems collapsed and healthcare professionals had to be on the front line of this crisis. The adverse effects on the mental health of healthcare professionals have been widely reported. This research focuses on identifying the main factors associated with adverse psychological outcomes.

MethodsDescriptive, cross-sectional study based on surveys, applying the PHQ-9, GAD-7, ISI and EIE-R tests to healthcare professionals from Ecuador during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results1028 participants, distributed in: 557 physicians (54.18%), 349 nurses (33.94%), 29 laboratory workers (2.82%), 27 paramedics (2.62%), 52 psychologists (5.05%) and 14 respiratory therapists (1.36%), from 16 of the 24 provinces of Ecuador. Of these, 27.3% presented symptoms of depression, 39.2% anxiety symptoms, 16.3% insomnia and 43.8% symptoms of PTSD, with the 4 types of symptoms ranging from moderate to severe. The most relevant associated factors were: working in Guayas (the most affected province) (OR = 2.18 for depressive symptoms and OR = 2.59 for PTSD symptoms); being a postgraduate doctor (OR = 1.52 for depressive symptoms and OR = 1.57 for insomnia), perception of not having the proper protective equipment (OR = 1.71 for symptoms of depression and OR = 1.57 for symptoms of anxiety) and being a woman (OR = 1.39 for anxiety).

ConclusionsHealthcare professionals can suffer a significant mental condition that may require psychiatric and psychological intervention. The main associated factors are primarily related to living and working in cities with a higher number of cases and the characteristics of the job, such as being a postgraduate doctor, as well as the perception of security. The main risk factors are primarily related to geographical distribution and job characteristics, such as being a resident physician and self-perception of safety. Further studies are required as the pandemic evolves.

Desde la aparición de la enfermedad por el nuevo coronavirus de 2019 (COVID-19), el mundo se enfrentó a una pandemia con consecuencias a todo nivel. En muchos países los sistemas de salud se han visto colapsados y el personal de salud ha tenido que enfrentarse a esta crisis en primera línea. Los efectos adversos sobre la salud mental del personal sanitario han sido ampliamente reportados. La presente investigación se enfoca en identificar los principales factores asociados con efectos adversos psicológicos.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo, transversal, basado en encuestas, aplicando los test PHQ-9, GAD-7, ISI y EIE-R a personal de salud de Ecuador durante la pandemia de COVID-19.

ResultadosParticiparon 1.028 personas, distribuidas en: 557 médicos (54,18%), 349 enfermeras (33,94%), 29 laboratoristas (2,82%), 27 paramédicos (2,62%), 52 psicólogos (5,05%) y 14 terapeutas respiratorios (1,36%), de 16 de las 24 provincias de Ecuador. El 27,3% tenía síntomas de depresión; el 39,2%, síntomas de ansiedad; el 16,3%, insomnio y el 43,8%, síntomas de TEPT; los 4 tipos de síntomas iban de moderados a graves. Los factores asociados más relevantes fueron: trabajar en Guayas (la provincia más afectada) (OR = 2,18 para síntomas depresivos y OR = 2,59 para síntomas de TEPT); ser médico posgradista (OR = 1,52 para síntomas depresivos y OR = 1,57 para insomnio), percepción de no contar con el equipo de protección adecuado (OR = 1,71 para síntomas de depresión y OR = 1,57 para síntomas de ansiedad) y ser mujer (OR = 1,39 para ansiedad).

ConclusionesEl personal de salud puede tener una afección mental importante que puede requerir intervención médica psiquiátrica y psicológica. Los principales factores asociados se relacionan sobre todo con vivir y trabajar en ciudades con mayor número de casos y las características del trabajo, como ser médico posgradista, así como la percepción propia de seguridad. Se requiere realizar más estudios según evolucione la pandemia.

In 2020, Ecuador, like other countries, was affected by the pandemic of a new type of acute respiratory syndrome caused by a recently identified beta coronavirus first reported in Wuhan, China.1,2 On 30 January, a global public health emergency was declared, and since then the disease has continued to spread at varying rates in each country and continent. On 11 February 2020, the World Health Organisation named it coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).3 In Ecuador, by 1 April 2020, there were 2240 confirmed cases and 75 deaths attributable to COVID-19 according to official data.4

Among the preventive measures, many affected countries chose to limit the free movement of their populations. In Ecuador, as measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19, most commercial activities were suspended and other essential activities were maintained, but with restricted hours. However, because of the medical emergency, healthcare services remained in operation with only slight modifications in working hours. Different studies have shown that healthcare staff are already under a great deal of stress under normal conditions in relation to individual factors, both objective and subjective, and the physical environment.5

In a number of countries, there is evidence that healthcare workers' mental health has been affected during the pandemic, with high scores in screening tests for depression, anxiety, insomnia and distress as a result of the events they have experienced. Risk factors reported for higher scores in the psychometric tests were being female and working in nursing, on the front line and in the geographic location of the primary outbreak.6 Studies carried out in Italy determined that some of the factors associated with negative psychological symptoms were being female and being young.6,7 Another study showed that the risk factors in the general population are no different from those found in the population represented by healthcare workers,8 which is striking considering the nature of the work carried out by this group, providing direct front line medical care. However, these results have been questioned as they have not been reproduced in other studies. A study carried out in Spain found an association between psychosocial work conditions and mental health disorders in workers,9 situations that are easily reproducible in a time of pandemic such as the current COVID-19 crisis.

The increasing number of cases, a shortage of medical staff, the build-up of working hours because of the crisis and the latent risk of infection are just some of the factors that increase internal stress. This can lead to the development of mental disorders, with symptoms of depression and anxiety, insomnia and distress that can last long after the crisis is resolved and require specialised care.6,10–15

There are data from researchers from different countries and continents, but it is vital to establish a profile of how healthcare workers in Ecuador are affected and the factors associated with mental health disorders of this type, and then the results can be compared with those obtained in China. One of the main benefits we are hoping for is to be able to provide timely and comprehensive care for healthcare personnel having to deal with the current critical situation caused by COVID-19.

MethodsDescriptive, cross-sectional, survey-based study conducted from 30 March to 22 April 2020 using a survey that included self-administered tests. The exclusively research and academic objectives of the study were explained to each participant and their informed consent was obtained after they had read and signed the consent form agreeing to take part. Participation was anonymous and voluntary. The participants had the option to withdraw at any point. All information was processed in a confidential database.

Voluntary participation was requested from doctors, nurses, paramedics, psychologists and respiratory therapists from various cities in Ecuador, regardless of geographical area. The survey was given to both healthcare personnel who worked directly with patients with suspected or confirmed COVID 19 and those who did not have contact with these patients.

VariablesThe symptoms investigated were: depression, using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)16; anxiety, with the generalised anxiety disorder test (GAD-7)17; insomnia, with the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI)18; and the reaction to stress with the revised impact of event scale (IES) for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).19 The Spanish language-validated versions were used for all these scales or questionnaires.

The scales were interpreted according to their respective guidelines and recommendations16–19:

- •

PHQ-9 (0–27): <4 normal; 5–9 mild depression; 10–14 moderate depression; and >15 severe depression.

- •

GAD-7 (0–21): <4 normal; 5–9 mild anxiety; 10–14 moderate anxiety; and >15 severe anxiety.

- •

ISI (0–28): <7 normal; 8–14 subthreshold insomnia; 15–21 moderate insomnia; and >22 severe insomnia.

- •

IES (0–88): <8 normal; 9–25 mild; 26–43 moderate; and >44 severe.

The patients' sociodemographic data were collected simultaneously in the same survey with the psychometric tests. They were asked about gender (male and female), province of work and residence, as well as whether they lived in the same province as their work (yes or no), occupation (doctor, nurse, laboratory specialist, paramedic, psychologist or respiratory therapist), age, divided into ranges (18−25, 26−30, 30–40 and >40 years of age), marital status (with or without a stable partner), type of institution where they worked (primary, secondary or tertiary level according to the classification of the Ecuador Ministry of Public Health), contact with patients suspected of having COVID-19 infection (yes or no) and, lastly, their perception of having the necessary protective measures (yes or no). Last of all, for the demographic variable, where respondents were located according to their workplace, the provinces were grouped into northern, southern and coastal, leaving Pichincha and Guayas as independent areas because they are the most populated and the most affected by the pandemic.

Statistical analysisA digital database was created, which was analysed with Python 3 software with Pandas, Sklearn and Scipy statistical libraries, with a significance level of 0.05. For the descriptive analysis, qualitative variables are presented as a percentage, while quantitative variables are shown by median [interquartile range]. The tests were analysed according to the established interpretation intervals. For inferential statistics, multinomial logistic regression analysis was used. Distractor variables were eliminated from each model and in a second phase only variables with P < .05 were taken. A logistic regression was carried out to assess the factors that influenced the development of moderate and severe symptoms for each group of symptoms studied: depression, anxiety, insomnia and reaction to stress. The association between risk factors and symptoms suffered by staff is presented as odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Based on the geographic variable, a random oversampling process was performed to provide more precision and accuracy to the data through greater representativeness of areas with fewer data.

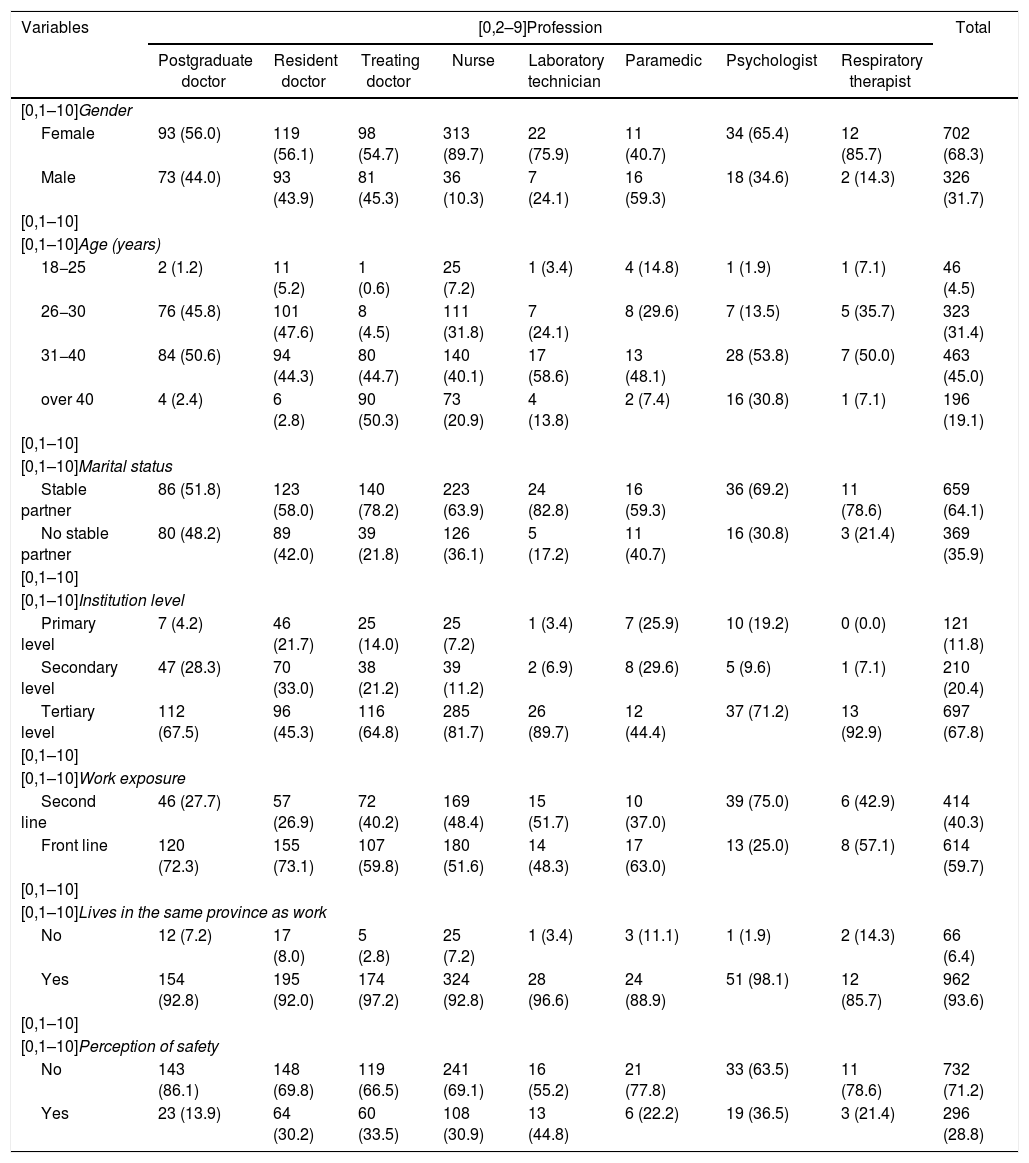

ResultsA total of 1060 healthcare workers responded to the survey, but 32 were excluded for meeting exclusion criteria. The sample of 1028 individuals was made up of 557 doctors (54.18%), 349 nurses (33.94%), 29 laboratory technicians (2.82%), 27 paramedics (2.62%), 52 psychologists (5.05%) and 14 respiratory therapists (1.36%). They were distributed throughout Ecuador, being healthcare professionals who lived and/or worked in 16 of the country's 24 provinces; Guayas, Manabí and Pichincha were the provinces with the highest number of cases. Of the sample of respondents, 326 were male (31.7%) and 702 female (68.3%). The largest age group was 31−40, accounting for 463 participants (45%), 659 (64.1%) were in a stable relationship, 697 (67.8%) worked in a tertiary level hospital according to the Ministry of Public Health classification, 614 (59.7%) were also on the front line caring for COVID-19 patients, 962 (93.6%) lived in the same province as their work and 732 (71.2%) did not have the perception of being safe (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics by profession.

| Variables | [0,2–9]Profession | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postgraduate doctor | Resident doctor | Treating doctor | Nurse | Laboratory technician | Paramedic | Psychologist | Respiratory therapist | ||

| [0,1–10]Gender | |||||||||

| Female | 93 (56.0) | 119 (56.1) | 98 (54.7) | 313 (89.7) | 22 (75.9) | 11 (40.7) | 34 (65.4) | 12 (85.7) | 702 (68.3) |

| Male | 73 (44.0) | 93 (43.9) | 81 (45.3) | 36 (10.3) | 7 (24.1) | 16 (59.3) | 18 (34.6) | 2 (14.3) | 326 (31.7) |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Age (years) | |||||||||

| 18−25 | 2 (1.2) | 11 (5.2) | 1 (0.6) | 25 (7.2) | 1 (3.4) | 4 (14.8) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (7.1) | 46 (4.5) |

| 26−30 | 76 (45.8) | 101 (47.6) | 8 (4.5) | 111 (31.8) | 7 (24.1) | 8 (29.6) | 7 (13.5) | 5 (35.7) | 323 (31.4) |

| 31−40 | 84 (50.6) | 94 (44.3) | 80 (44.7) | 140 (40.1) | 17 (58.6) | 13 (48.1) | 28 (53.8) | 7 (50.0) | 463 (45.0) |

| over 40 | 4 (2.4) | 6 (2.8) | 90 (50.3) | 73 (20.9) | 4 (13.8) | 2 (7.4) | 16 (30.8) | 1 (7.1) | 196 (19.1) |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Marital status | |||||||||

| Stable partner | 86 (51.8) | 123 (58.0) | 140 (78.2) | 223 (63.9) | 24 (82.8) | 16 (59.3) | 36 (69.2) | 11 (78.6) | 659 (64.1) |

| No stable partner | 80 (48.2) | 89 (42.0) | 39 (21.8) | 126 (36.1) | 5 (17.2) | 11 (40.7) | 16 (30.8) | 3 (21.4) | 369 (35.9) |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Institution level | |||||||||

| Primary level | 7 (4.2) | 46 (21.7) | 25 (14.0) | 25 (7.2) | 1 (3.4) | 7 (25.9) | 10 (19.2) | 0 (0.0) | 121 (11.8) |

| Secondary level | 47 (28.3) | 70 (33.0) | 38 (21.2) | 39 (11.2) | 2 (6.9) | 8 (29.6) | 5 (9.6) | 1 (7.1) | 210 (20.4) |

| Tertiary level | 112 (67.5) | 96 (45.3) | 116 (64.8) | 285 (81.7) | 26 (89.7) | 12 (44.4) | 37 (71.2) | 13 (92.9) | 697 (67.8) |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Work exposure | |||||||||

| Second line | 46 (27.7) | 57 (26.9) | 72 (40.2) | 169 (48.4) | 15 (51.7) | 10 (37.0) | 39 (75.0) | 6 (42.9) | 414 (40.3) |

| Front line | 120 (72.3) | 155 (73.1) | 107 (59.8) | 180 (51.6) | 14 (48.3) | 17 (63.0) | 13 (25.0) | 8 (57.1) | 614 (59.7) |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Lives in the same province as work | |||||||||

| No | 12 (7.2) | 17 (8.0) | 5 (2.8) | 25 (7.2) | 1 (3.4) | 3 (11.1) | 1 (1.9) | 2 (14.3) | 66 (6.4) |

| Yes | 154 (92.8) | 195 (92.0) | 174 (97.2) | 324 (92.8) | 28 (96.6) | 24 (88.9) | 51 (98.1) | 12 (85.7) | 962 (93.6) |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]Perception of safety | |||||||||

| No | 143 (86.1) | 148 (69.8) | 119 (66.5) | 241 (69.1) | 16 (55.2) | 21 (77.8) | 33 (63.5) | 11 (78.6) | 732 (71.2) |

| Yes | 23 (13.9) | 64 (30.2) | 60 (33.5) | 108 (30.9) | 13 (44.8) | 6 (22.2) | 19 (36.5) | 3 (21.4) | 296 (28.8) |

Values are expressed as n (%).

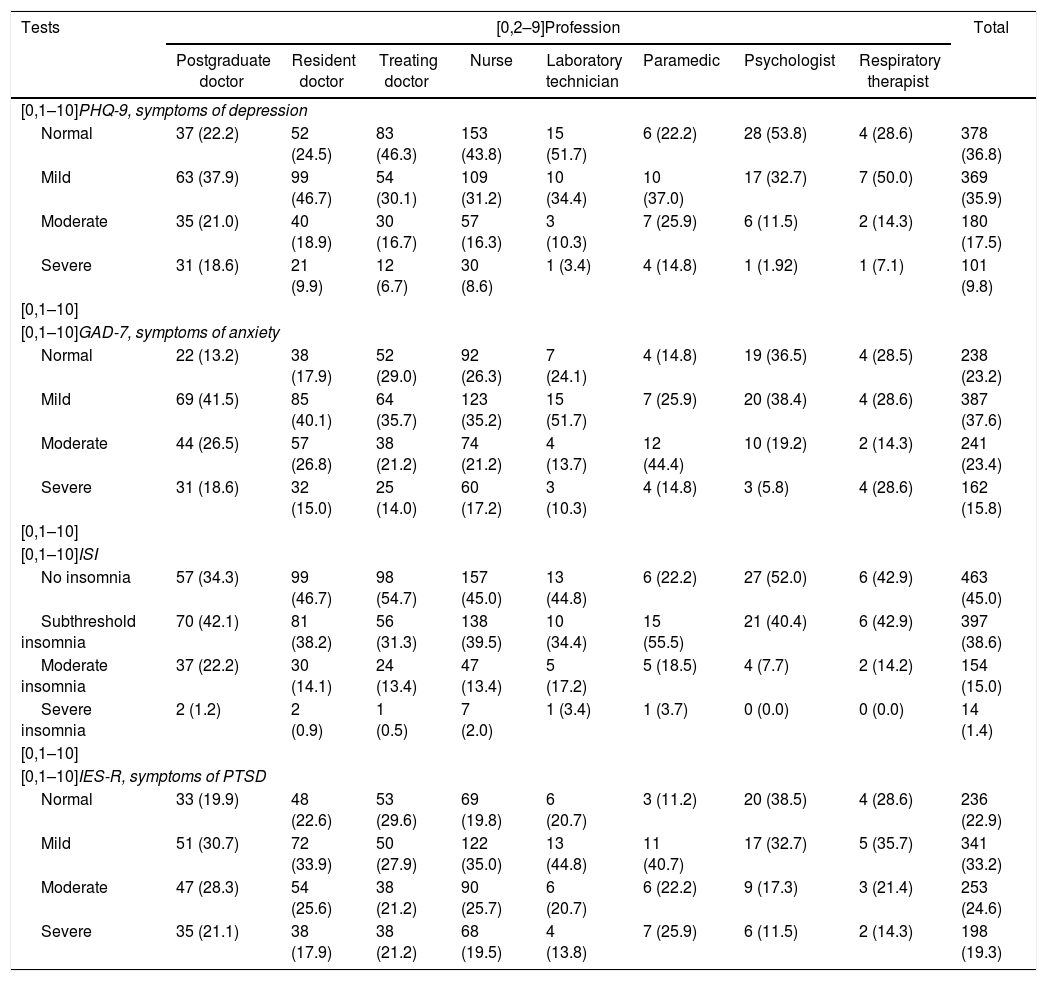

The following data were obtained from the tests completed: in the PHQ-9 test, there was a median of 7 [3–10] and 27.3% of the respondents had scores in the moderate and severe depression ranges; in the GAD-7 test, the median was 7 [5–12] and 39.2% of the scores denoted moderate or severe anxiety; on the ISI scale, the median was 9 [4–13] and 16.3% were in the moderate and severe insomnia ranges; and on the IES scale, the median was 29 [10–39] and 43.8% had moderate to severe PTSD symptoms (Table 2).

Interpretation of test scores according to profession.

| Tests | [0,2–9]Profession | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postgraduate doctor | Resident doctor | Treating doctor | Nurse | Laboratory technician | Paramedic | Psychologist | Respiratory therapist | ||

| [0,1–10]PHQ-9, symptoms of depression | |||||||||

| Normal | 37 (22.2) | 52 (24.5) | 83 (46.3) | 153 (43.8) | 15 (51.7) | 6 (22.2) | 28 (53.8) | 4 (28.6) | 378 (36.8) |

| Mild | 63 (37.9) | 99 (46.7) | 54 (30.1) | 109 (31.2) | 10 (34.4) | 10 (37.0) | 17 (32.7) | 7 (50.0) | 369 (35.9) |

| Moderate | 35 (21.0) | 40 (18.9) | 30 (16.7) | 57 (16.3) | 3 (10.3) | 7 (25.9) | 6 (11.5) | 2 (14.3) | 180 (17.5) |

| Severe | 31 (18.6) | 21 (9.9) | 12 (6.7) | 30 (8.6) | 1 (3.4) | 4 (14.8) | 1 (1.92) | 1 (7.1) | 101 (9.8) |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]GAD-7, symptoms of anxiety | |||||||||

| Normal | 22 (13.2) | 38 (17.9) | 52 (29.0) | 92 (26.3) | 7 (24.1) | 4 (14.8) | 19 (36.5) | 4 (28.5) | 238 (23.2) |

| Mild | 69 (41.5) | 85 (40.1) | 64 (35.7) | 123 (35.2) | 15 (51.7) | 7 (25.9) | 20 (38.4) | 4 (28.6) | 387 (37.6) |

| Moderate | 44 (26.5) | 57 (26.8) | 38 (21.2) | 74 (21.2) | 4 (13.7) | 12 (44.4) | 10 (19.2) | 2 (14.3) | 241 (23.4) |

| Severe | 31 (18.6) | 32 (15.0) | 25 (14.0) | 60 (17.2) | 3 (10.3) | 4 (14.8) | 3 (5.8) | 4 (28.6) | 162 (15.8) |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]ISI | |||||||||

| No insomnia | 57 (34.3) | 99 (46.7) | 98 (54.7) | 157 (45.0) | 13 (44.8) | 6 (22.2) | 27 (52.0) | 6 (42.9) | 463 (45.0) |

| Subthreshold insomnia | 70 (42.1) | 81 (38.2) | 56 (31.3) | 138 (39.5) | 10 (34.4) | 15 (55.5) | 21 (40.4) | 6 (42.9) | 397 (38.6) |

| Moderate insomnia | 37 (22.2) | 30 (14.1) | 24 (13.4) | 47 (13.4) | 5 (17.2) | 5 (18.5) | 4 (7.7) | 2 (14.2) | 154 (15.0) |

| Severe insomnia | 2 (1.2) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.5) | 7 (2.0) | 1 (3.4) | 1 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 14 (1.4) |

| [0,1–10] | |||||||||

| [0,1–10]IES-R, symptoms of PTSD | |||||||||

| Normal | 33 (19.9) | 48 (22.6) | 53 (29.6) | 69 (19.8) | 6 (20.7) | 3 (11.2) | 20 (38.5) | 4 (28.6) | 236 (22.9) |

| Mild | 51 (30.7) | 72 (33.9) | 50 (27.9) | 122 (35.0) | 13 (44.8) | 11 (40.7) | 17 (32.7) | 5 (35.7) | 341 (33.2) |

| Moderate | 47 (28.3) | 54 (25.6) | 38 (21.2) | 90 (25.7) | 6 (20.7) | 6 (22.2) | 9 (17.3) | 3 (21.4) | 253 (24.6) |

| Severe | 35 (21.1) | 38 (17.9) | 38 (21.2) | 68 (19.5) | 4 (13.8) | 7 (25.9) | 6 (11.5) | 2 (14.3) | 198 (19.3) |

GAD: generalised anxiety disorder; IES-R: Impact of Event Scale-Revised; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder.

Values are expressed as n (%).

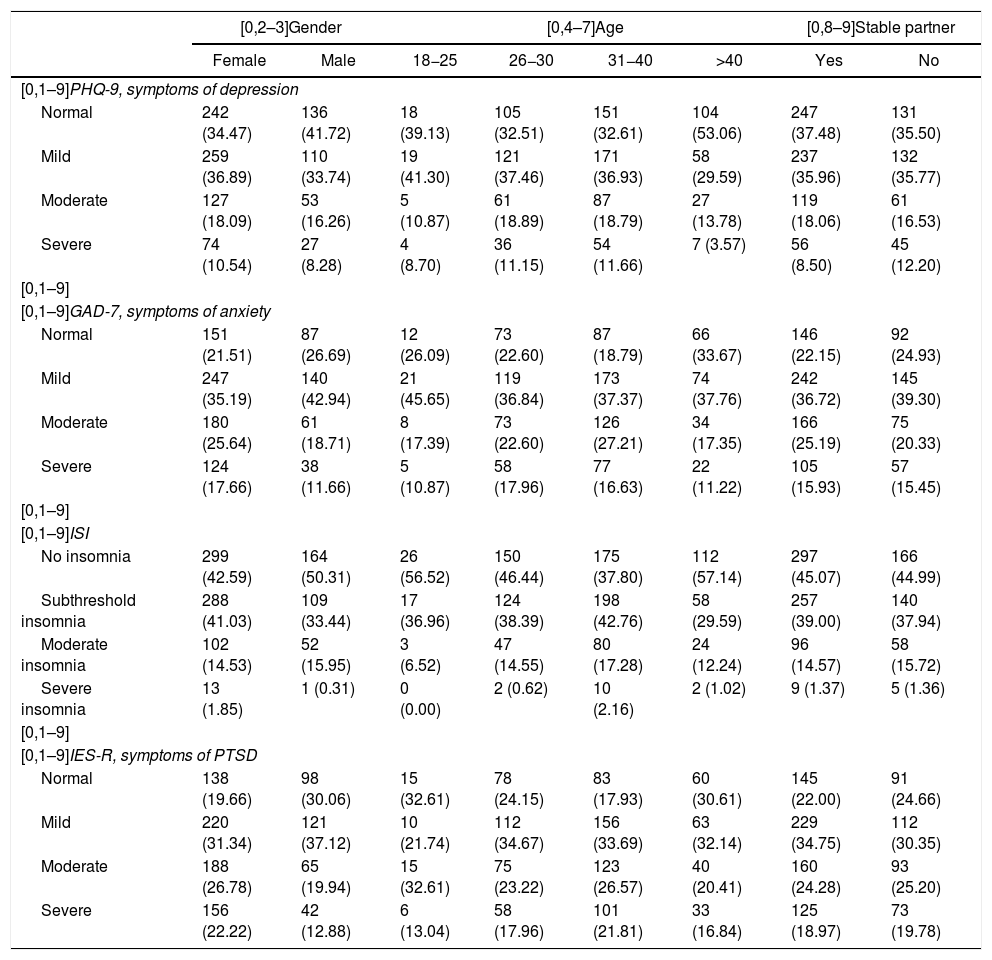

Table 3 shows the distribution of the interpretation of the scores for the different tests according to each of the variables studied.

Interpretation of test scores according to variables.

| [0,2–3]Gender | [0,4–7]Age | [0,8–9]Stable partner | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | 18−25 | 26−30 | 31−40 | >40 | Yes | No | |

| [0,1–9]PHQ-9, symptoms of depression | ||||||||

| Normal | 242 (34.47) | 136 (41.72) | 18 (39.13) | 105 (32.51) | 151 (32.61) | 104 (53.06) | 247 (37.48) | 131 (35.50) |

| Mild | 259 (36.89) | 110 (33.74) | 19 (41.30) | 121 (37.46) | 171 (36.93) | 58 (29.59) | 237 (35.96) | 132 (35.77) |

| Moderate | 127 (18.09) | 53 (16.26) | 5 (10.87) | 61 (18.89) | 87 (18.79) | 27 (13.78) | 119 (18.06) | 61 (16.53) |

| Severe | 74 (10.54) | 27 (8.28) | 4 (8.70) | 36 (11.15) | 54 (11.66) | 7 (3.57) | 56 (8.50) | 45 (12.20) |

| [0,1–9] | ||||||||

| [0,1–9]GAD-7, symptoms of anxiety | ||||||||

| Normal | 151 (21.51) | 87 (26.69) | 12 (26.09) | 73 (22.60) | 87 (18.79) | 66 (33.67) | 146 (22.15) | 92 (24.93) |

| Mild | 247 (35.19) | 140 (42.94) | 21 (45.65) | 119 (36.84) | 173 (37.37) | 74 (37.76) | 242 (36.72) | 145 (39.30) |

| Moderate | 180 (25.64) | 61 (18.71) | 8 (17.39) | 73 (22.60) | 126 (27.21) | 34 (17.35) | 166 (25.19) | 75 (20.33) |

| Severe | 124 (17.66) | 38 (11.66) | 5 (10.87) | 58 (17.96) | 77 (16.63) | 22 (11.22) | 105 (15.93) | 57 (15.45) |

| [0,1–9] | ||||||||

| [0,1–9]ISI | ||||||||

| No insomnia | 299 (42.59) | 164 (50.31) | 26 (56.52) | 150 (46.44) | 175 (37.80) | 112 (57.14) | 297 (45.07) | 166 (44.99) |

| Subthreshold insomnia | 288 (41.03) | 109 (33.44) | 17 (36.96) | 124 (38.39) | 198 (42.76) | 58 (29.59) | 257 (39.00) | 140 (37.94) |

| Moderate insomnia | 102 (14.53) | 52 (15.95) | 3 (6.52) | 47 (14.55) | 80 (17.28) | 24 (12.24) | 96 (14.57) | 58 (15.72) |

| Severe insomnia | 13 (1.85) | 1 (0.31) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.62) | 10 (2.16) | 2 (1.02) | 9 (1.37) | 5 (1.36) |

| [0,1–9] | ||||||||

| [0,1–9]IES-R, symptoms of PTSD | ||||||||

| Normal | 138 (19.66) | 98 (30.06) | 15 (32.61) | 78 (24.15) | 83 (17.93) | 60 (30.61) | 145 (22.00) | 91 (24.66) |

| Mild | 220 (31.34) | 121 (37.12) | 10 (21.74) | 112 (34.67) | 156 (33.69) | 63 (32.14) | 229 (34.75) | 112 (30.35) |

| Moderate | 188 (26.78) | 65 (19.94) | 15 (32.61) | 75 (23.22) | 123 (26.57) | 40 (20.41) | 160 (24.28) | 93 (25.20) |

| Severe | 156 (22.22) | 42 (12.88) | 6 (13.04) | 58 (17.96) | 101 (21.81) | 33 (16.84) | 125 (18.97) | 73 (19.78) |

| [0,2–4]Institution level | [0,5–6]Contact with suspected COVID-19 patient | [0,7–8]Perception of having adequate protective measures | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary level | Secondary level | Tertiary level | Yes | No | Yes | No | |

| [0,1–8]PHQ-9, symptoms of depression | |||||||

| Normal | 40 (33.06) | 59 (28.10) | 279 (40.03) | 180 (29.32) | 198 (47.83) | 174 (58.78) | 204 (27.87) |

| Mild | 45 (37.19) | 89 (42.38) | 235 (33.72) | 231 (37.62) | 138 (33.33) | 81 (27.36) | 288 (39.34) |

| Moderate | 25 (20.66) | 35 (16.67) | 120 (17.22) | 131 (21.34) | 49 (11.84) | 27 (9.12) | 153 (20.90) |

| Severe | 11 (9.09) | 27 (12.86) | 63 (9.04) | 72 (11.73) | 29 (7.00) | 14 (4.73) | 87 (11.89) |

| [0,1–8] | |||||||

| [0,1–8]GAD-7, symptoms of anxiety | |||||||

| Normal | 31 (25.62) | 31 (14.76) | 176 (25.25) | 99 (16.12) | 139 (33.57) | 108 (36.49) | 130 (17.76) |

| Mild | 37 (30.58) | 87 (41.43) | 263 (37.73) | 236 (38.44) | 151 (36.47) | 115 (38.85) | 272 (37.16) |

| Moderate | 30 (24.79) | 59 (28.10) | 152 (21.81) | 158 (25.73) | 83 (20.05) | 50 (16.89) | 191 (26.09) |

| Severe | 23 (19.01) | 33 (15.71) | 106 (15.21) | 121 (19.71) | 41 (9.90) | 23 (7.77) | 139 (18.99) |

| [0,1–8] | |||||||

| [0,1–8]ISI | |||||||

| No insomnia | 51 (42.15) | 80 (38.10) | 332 (47.63) | 252 (41.04) | 211 (50.97) | 185 (62.50) | 278 (37.98) |

| Subthreshold insomnia | 50 (41.32) | 91 (43.33) | 256 (36.73) | 245 (39.90) | 152 (36.71) | 87 (29.39) | 310 (42.35) |

| Moderate insomnia | 18 (14.88) | 37 (17.62) | 99 (14.20) | 108 (17.59) | 46 (11.11) | 23 (7.77) | 131 (17.90) |

| Severe insomnia | 2 (1.65) | 2 (0.95) | 10 (1.43) | 9 (1.47) | 5 (1.21) | 1 (0.34) | 13 (1.78) |

| [0,1–8] | |||||||

| [0,1–8]IES-R, symptoms of PTSD | |||||||

| Normal | 31 (25.62) | 40 (19.05) | 165 (23.67) | 116 (18.89) | 120 (28.99) | 99 (33.45) | 137 (18.72) |

| Mild | 31 (25.62) | 82 (39.05) | 228 (32.71) | 190 (30.94) | 151 (36.47) | 108 (36.49) | 233 (31.83) |

| Moderate | 35 (28.93) | 48 (22.86) | 170 (24.39) | 166 (27.04) | 87 (21.01) | 64 (21.62) | 189 (25.82) |

| Severe | 24 (19.83) | 40 (19.05) | 134 (19.23) | 142 (23.13) | 56 (13.53) | 25 (8.45) | 173 (23.63) |

GAD: generalised anxiety disorder; IES-R: Impact of Event Scale-Revised; ISI: Insomnia Severity Index; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder.

Values are expressed as n (%).

Logistic regression was applied to all the tests in two ways: first, considering the severe form of each type of symptom; and second, considering the moderate and severe forms.

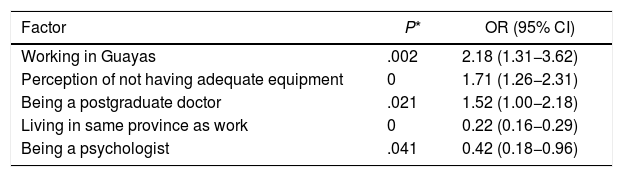

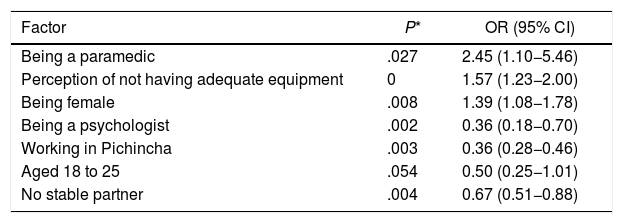

Symptoms of depression (PHQ-9)When analysed using logistic regression, the results for the PHQ-9 test that denoted symptoms of depression showed that the most important risk factors for suffering from moderate to severe symptoms were working in the province of Guayas, being a postgraduate doctor and the perception of not having adequate equipment. In contrast, the protective factors were being a psychologist and living in the same province as work. The odds ratios (OR) and their confidence intervals are shown in Table 4.

Factors associated with moderate and severe symptoms of depression.

| Factor | P* | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Working in Guayas | .002 | 2.18 (1.31−3.62) |

| Perception of not having adequate equipment | 0 | 1.71 (1.26−2.31) |

| Being a postgraduate doctor | .021 | 1.52 (1.00−2.18) |

| Living in same province as work | 0 | 0.22 (0.16−0.29) |

| Being a psychologist | .041 | 0.42 (0.18−0.96) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

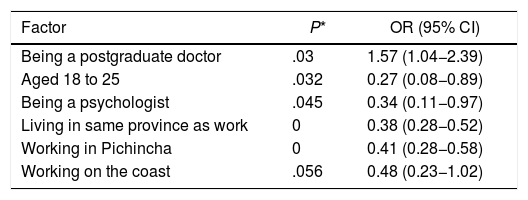

For anxiety symptoms measured with the GAD-7 test, the main risk factors for developing moderate to severe symptoms were being a paramedic, the perception of not having adequate equipment and being female. The protective factors were being a psychologist, working in Pichincha, being in the 18−25 age group and not having a stable partner. The OR and their confidence intervals are shown in Table 5.

Factors associated with moderate-to-severe anxiety symptoms.

| Factor | P* | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Being a paramedic | .027 | 2.45 (1.10−5.46) |

| Perception of not having adequate equipment | 0 | 1.57 (1.23−2.00) |

| Being female | .008 | 1.39 (1.08−1.78) |

| Being a psychologist | .002 | 0.36 (0.18−0.70) |

| Working in Pichincha | .003 | 0.36 (0.28−0.46) |

| Aged 18 to 25 | .054 | 0.50 (0.25−1.01) |

| No stable partner | .004 | 0.67 (0.51−0.88) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

The main risk factor for moderate and severe insomnia revealed by the ISI test was being a postgraduate doctor. The protective factors were being in the 18−25 age group, being a psychologist, living in the same province as work, working in Pichincha and working on the Coast. The OR and their confidence intervals are shown in Table 6.

Factors associated with moderate-to-severe insomnia.

| Factor | P* | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Being a postgraduate doctor | .03 | 1.57 (1.04−2.39) |

| Aged 18 to 25 | .032 | 0.27 (0.08−0.89) |

| Being a psychologist | .045 | 0.34 (0.11−0.97) |

| Living in same province as work | 0 | 0.38 (0.28−0.52) |

| Working in Pichincha | 0 | 0.41 (0.28−0.58) |

| Working on the coast | .056 | 0.48 (0.23−1.02) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio.

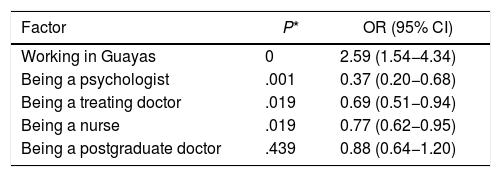

Lastly, the logistic regression of the results of the IES test measuring symptoms of PTSD and reaction to stress showed that the main risk factor was working in the province of Guayas, while the protective factors were being a postgraduate doctor, treating doctor, psychologist or nurse. The OR and their confidence intervals are shown in Table 7.

Factors associated with moderate-to-severe PTSD symptoms.

| Factor | P* | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Working in Guayas | 0 | 2.59 (1.54−4.34) |

| Being a psychologist | .001 | 0.37 (0.20−0.68) |

| Being a treating doctor | .019 | 0.69 (0.51−0.94) |

| Being a nurse | .019 | 0.77 (0.62−0.95) |

| Being a postgraduate doctor | .439 | 0.88 (0.64−1.20) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder.

It is striking that having contact with patients with suspected COVID-19 was not a factor in any of the symptom types assessed.

DiscussionThis study was conducted by distributing validated tests to healthcare professionals working in most of Ecuador's provinces. Most of the participants were female, aged 31−40 and had a stable partner. They worked in tertiary level units, were in contact with patients with suspected COVID-19 and had the perception of not having adequate safety measures to carry out their work. Analysing the tests by their respective interpretation intervals, it was found that 36.77% had normal values for depressive symptoms; 23.44% were in the normal range for anxiety symptoms; 45.04% had normal sleep; and only 22.96% had scores within normal range for PTSD symptoms. This shows that most of the respondents had abnormal scores in the tests, indicating that they had adverse psychological symptoms. The least affected area was sleeping routine, in contrast to other studies in which sleep was more affected.8 In our study, the most affected area was that related to PTSD symptoms and reaction to stress; the IES test recorded the highest number of interpretations in the severe symptom band (19.26%). The development of psychiatric symptoms has been found in many studies carried out around the world.6,7,15

These results need to be framed in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the most likely explanation is the fear of possible contagion and also of infecting close friends and family. The unease and distress caused by having to deal with a relatively new disease for which data on morbidity and mortality rates continue to be uncertain should also be taken into account. The growing number of deaths in the country increases psychological stress among healthcare workers.

The inferential statistical analysis revealed that the factors associated with suffering moderate or severe psychological adverse events had a particular distribution for each pattern of symptoms. Of the variables studied, only three were shown to be factors associated with more than one type of symptom. The first was working in the province of Guayas, which was associated with symptoms of depression and PTSD, and the second was being a postgraduate doctor, associated with depression and anxiety. A possible explanation for these variables could be that Guayas has been the most affected province in Ecuador since the beginning of the pandemic and coinciding with the conduct of the study. The fact that being a postgraduate doctor was an associated factor may be related to their heavy workload as a requirement of their training and the independent working conditions for each healthcare unit and specialist area. It is important to bear in mind, however, that being a postgraduate doctor was found to be a factor associated with a low likelihood of suffering from PTSD symptoms and reaction to stress, although this may be related to better mechanisms of resilience and coping with stressful situations.20,21 In addition, the experience of being involved in activities such as patient care during the crisis possibly creates a protective effect against PTSD symptoms. The third and last factor associated with two types of symptom was the perception of not having adequate protective equipment, which was associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety. It is important to stress that this variable is clearly the perception of each individual healthcare worker, without any type of verification. However, a person's own perception significantly influences their personal feeling of safety and, if they do not have that, it can lead to adverse events such as those described. It is interesting that it loses importance when considering insomnia or PTSD symptoms. It should be noted that the last risk factor with statistical significance was being female, but only for anxiety symptoms. This is in contrast to other studies in which being female was also associated with other psychiatric symptoms.6,7

Of the factors with a statistical association with a low likelihood of psychological adverse events, it is notable that being a psychologist is a protective variable in all the symptoms studied, possibly due to the nature of their training; we would recommend carrying out studies in the psychiatrist population. The other protective factors are almost entirely related to the geographical location of the workplace; the explanation for this is in the geographic distribution of the spread of the infection. Other relevant factors in the analysis associated with a low likelihood of psychological adverse events were: working in the same province where they lived for depression; being 18−25 and not having a stable partner for anxiety; and being a treating doctor or nurse for PTSD symptoms.

In the inferential statistics using logistic regression, the variable having contact with patients suspected of having COVID-19, that is, being on the front line, was a factor that had no significant association with the development of moderate or severe depression, anxiety, insomnia or PTSD symptoms, unlike other studies in which it has been established as an associated factor.6

LimitationsThe limitations of this study lie mainly in the characteristics of the type of survey, as several participants who were experiencing adverse psychological phenomena due to the stress generated by the pandemic refused to take part, which itself becomes a relevant factor. However, we did achieve a significant number of respondents. Secondly, the majority of the surveyed population lived in the province of Pichincha; to compensate for this limitation, random oversampling was performed to avoid statistical biases in the final results. Another limitation was the changes inherent to the pandemic, which caused fluctuations in stress levels and the coping mechanisms of both the population and healthcare personnel. It is important to highlight that this study was carried out during the months in which the pandemic was at its height in one of the most populated provinces of Ecuador. Meanwhile, studies into the behaviour of and possible treatments for COVID-19 are ongoing and the results from these could be factors that modify the distress felt by the Ecuadorian population in subsequent studies.

ConclusionsThe first conclusion from the data collected is that a large percentage of the healthcare workers had measurable psychological adverse effects in psychometric tests. Several factors that could be related to psychological adverse events were studied, but most of these did not show any association with the onset of these events. Of the factors studied in healthcare professionals, working in the Guayas province, the area most affected by the pandemic at the time of the study, being a postgraduate doctor, and perceiving that the necessary protective measures were not available signalled a greater likelihood of symptoms of anxiety, depression, PTSD and insomnia. Being female was also found to be a factor associated with anxiety symptoms. The factors associated with a low likelihood of psychological adverse effects were working in places without a high incidence of COVID-19 cases, being a psychologist, being a treating doctor and being a nurse. It should be added that being a postgraduate doctor was a factor associated with a low likelihood of PTSD symptoms.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Pazmiño Erazo EE, Alvear Velásquez MJ, Saltos Chávez IG, Pazmiño Pullas DE. Factores relacionados con efectos adversos psiquiátricos en personal de salud durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en Ecuador. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:166–175.