A delay in receiving an antipsychotic treatment is associated with unfavourable clinical and functional outcomes in patients with a first episode of psychosis. In recent years, early psychosis intervention programmes have been implemented that seek the early detection and treatment of patients who begin to describe psychotic symptoms. These programmes have shown to be more effective than standard care in improving the symptoms of the disorder and recovering the patient's functionality, in turn proving to be more cost-effective. The benefits of these programmes have led to their implementation in high-income countries. However, implementation in medium- and low-income countries has been slower. Peru, a Latin American country with an upper middle income, is undergoing a mental health reform that prioritises health care based on the prevention, treatment and psychosocial recovery of patients from a comprehensive and community approach. The present manuscript describes the characteristics and structure of the pioneering and more developed programmes for early psychosis intervention, and discusses the benefits and challenges of implementing an early psychosis intervention programme in Peru in the current context of mental health reform.

La demora en recibir un tratamiento antipsicótico se asocia con resultados desfavorables clínicos y funcionales en los pacientes con un primer episodio de psicosis. En los últimos años se han implementado programas de intervención temprana de psicosis que buscan detectar y tratar tempranamente a pacientes que empiezan a describir síntomas psicóticos. Estos programas se han mostrado más eficaces que los cuidados estándares en mejorar los síntomas del trastorno y recuperar la funcionalidad del paciente y, además, se han demostrado más costo-efectivos. Los beneficios de estos programas han promovido su implementación en países de ingresos económicos altos. Sin embargo, la implementación en países de ingresos económicos medianos y bajos ha sido más lenta. El Perú, país latinoamericano con un ingreso económico mediano alto, está atravesando una reforma en salud mental que prioriza la atención de salud con base en la prevención, el tratamiento y la recuperación psicosocial de los pacientes desde un enfoque integral y comunitario. El presente trabajo describe las características y la estructura de los programas pioneros y más desarrollados de intervención temprana de psicosis, y discute los beneficios y desafíos de la implementación de un programa de intervención temprana de psicosis en Perú en el contexto actual de reforma en salud mental.

The early stage of schizophrenia has been considered the critical period in the disorder because it is the stage in which the greatest decline in the person's health occurs.1 The development of frank psychotic symptoms marks the formal start of the first episode of schizophrenia, even if the disorder is not diagnosed for some time until the patient seeks or is taken to receive medical care.2 The period between the onset of psychotic symptoms and the start of suitable antipsychotic treatment is called the duration of untreated psychosis. It may last months or years.3,4 It has been postulated that during this period a toxic effect occurs by an as-yet-unknown neurological and psychological mechanism, causing irreversible damage in the individual.5 This argument has been supported by studies showing that a long duration of untreated psychosis is associated with a worse clinical condition, poor response to treatment and decrease in grey matter in patients who experience a first episode of psychosis.3,6–9 Hence, it has been proposed that reducing this period could improve short- and long-term clinical patient health outcomes.1,10

Patients with a first episode of psychosis who receive medical care present a variable response to treatment. Although most patients achieve an improvement in symptoms,11 there is a proportion of patients who do not achieve complete recovery or remain recurrence-free. For example, Robinson et al. showed that among patients with a first episode of psychosis, 47.2% achieved recovery from symptoms for two or more years and 25.5% achieved functional recovery. However, just 13.7% of patients achieved both clinical and functional recovery for two years or more.12 Caseiro et al. found that 65% of patients with a first episode of psychosis relapsed in the first three years of follow-up, and Robinson et al. found that up to 82% of patients relapsed in the first five years.13,14 Given that the greatest clinical and functional decline that accompanies psychotic disorders occurs within the first two to five years,15 recent decades have witnessed the implementation of programmes for early intervention in psychosis that actively intervene in the early stages of the disorder in pursuit of the patient's rapid clinical stabilisation and psychosocial rehabilitation.

Programmes for early intervention in psychosis are specialised mental health services that, from a clinical and research perspective, provide timely, comprehensive care to patients who present with psychotic symptoms.16 These programmes offer patients and their families hope of improving the person's health and disease course through various coordinated strategies.17 Some programmes also enrol people with prodromal symptoms of psychosis with the goal of preventing the development of a psychotic disorder.18 Various studies have shown that these programmes are more effective at improving patient health than standard care and furthermore have proven to be more cost-effective.19 Outcomes in favour of these programmes, which were initially implemented in Australia and Scandinavia,20 have led to the spread of interventions of this type to various countries, especially high-income countries.21 By contrast, in low- to middle-income countries, these programmes have not made their way into mental health systems, despite scientific evidence in favour of these interventions.22

Peru is a Latin American country with a middle to high income level according to the World Bank.23 Its budget allocated to mental health is low, and its mental health services have been concentrated in coastal cities.24 The mental health care received by patients with a psychotic disorder does not differ by the stage of their disorder; hence, patients with a first episode of psychosis receive the same care as patients in consolidated stages. In 2012, Peru implemented mental health reform that prioritises prevention, treatment and psychosocial recovery in patients with mental illnesses from a comprehensive, community-based approach.25 This has brought about a number of changes in the country's mental health system.26 This situation represents an opportunity to implement new interventions that are based on scientific evidence, focused on prevention and compliant with mental health reform guidelines. This study seeks to describe the structural characteristics of programmes for early intervention in psychosis and to discuss the potential benefits and difficulties of implementing such a programme in Peru's current mental health context.

Programmes for early intervention in psychosisSchizophrenia is conceived of as a chronic, debilitating and serious mental illness.27 Programmes for early intervention in psychosis seek to change this conception and improve the prognosis for the disorder with a set of coordinated strategies.16 The various programmes share a similar care model, but each one modifies its components and structure in accordance with its resources, objectives and needs.28 In general, programmes for early intervention in psychosis include multidisciplinary healthcare teams consisting of psychiatrists, nurses, social workers, occupational therapists and psychologists. The programmes operate with a low ratio of patients to healthcare professionals. This enables professionals to work closely with each patient.19 The strategies employed include pharmacological, psychotherapeutic, psychoeducational and social interventions, which are worked on with patients and their families.28 Regular meetings are held among team members to discuss each case individually.19 The programmes address not only matters related to the person's health, but also problems in their daily lives and interpersonal, occupational, economic and academic issues.19

Programmes for early intervention in psychosis differ from standard care in that they have two distinct features: early detection and specific treatment in phases.29 Early detection seeks to identify people with psychotic symptoms who have not received treatment. Strategies include training campaigns on psychotic symptoms and their treatment aimed at the general population as well as information campaigns aimed at general physicians, social workers and professors.30 Two studies showed that the use of early detection strategies as part of programmes for early intervention enabled identification of people with psychotic symptoms who were not being treated.30,31 Specific treatment in phases, for its part, includes the different strategies employed in the early stage of the disorder, such as drug treatment and cognitive, vocational and family therapies. These strategies are pursued jointly with the objective of promoting prompt patient recovery.29 These elements of programmes for early intervention in psychosis have exhibited positive middle- and long-term effects on the disorder.32

Programmes for early intervention in psychosis arose as local healthcare services and sought primarily to conduct research on initial episodes of psychosis.21 Subsequently, backed by studies that demonstrated their efficacy, these programmes were incorporated into the health systems of some countries and achieved nationwide coverage.21 For example, the Danish Parliament created competitive funds for regional health authorities to propose and implement programmes for early intervention in psychosis in different regions of Denmark.33 The Australian Federal Government adopted programmes for early intervention in psychosis as part of healthcare for the youth population and funded the implementation of these programmes nationwide.21 In the United States, the National Institute of Mental Health funded an early intervention programme for patients with a first episode of psychosis in 21 states.34 At present, programmes for early intervention have become the core treatment for patients who experience a first episode of psychosis in many countries.29

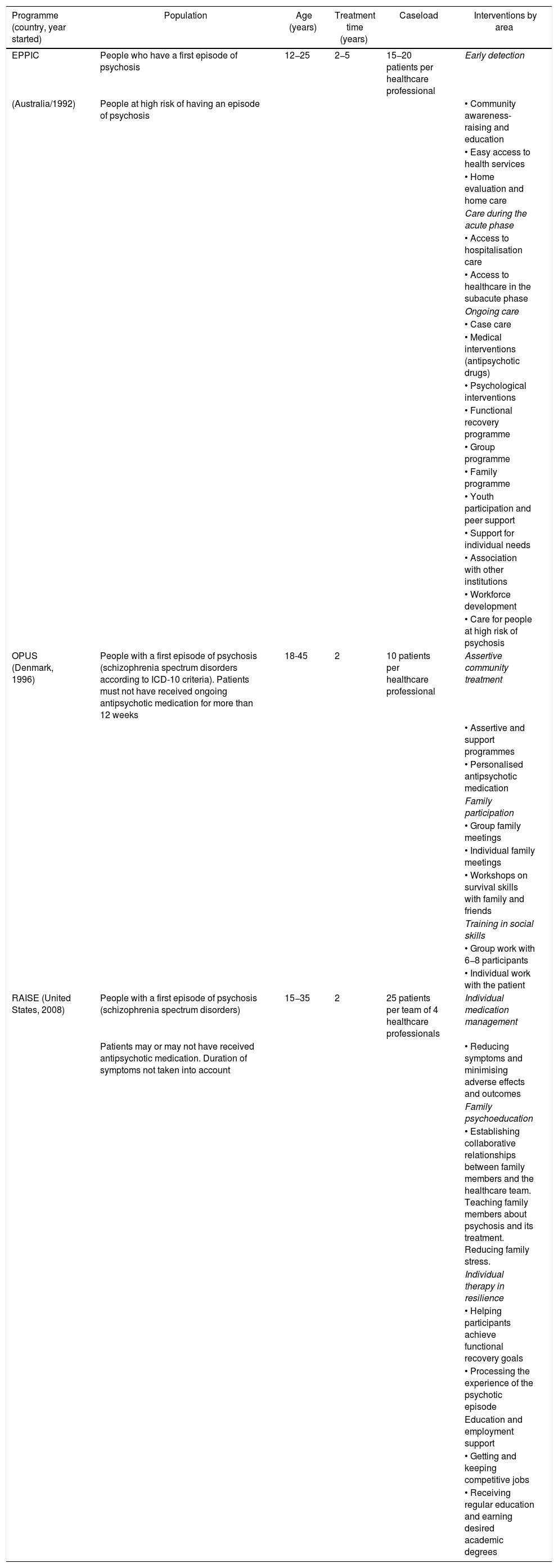

Experiences of programmes for early interventionA country's development of programmes for early intervention in psychosis is closely related to its economic development; the implementation process has been seen to be faster in developed countries than in developing countries.22 In Africa, the implementation process has been slow, whereas in Asia the development of these programmes has proceeded faster following the models of developed countries.22 In Latin America, until 2011, there were only seven centres for early intervention in psychosis, operating in Mexico and Brazil.35 These programmes were driven by universities as part of research studies, had local coverage and focused more on the prodromal stage of psychosis than on the first psychotic episode.35 The following programmes are described below: the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (EPPIC) in Australia,16,18 the OPUS programme in Denmark33,36 and the Recovery after an Initial Schizophrenia Episode (RAISE) programme in the United States.34,37 These programmes were selected due to being pioneers or well-developed in their countries. The main characteristics of these programmes are summarised in Table 1.

Characteristics of programmes for early intervention in psychosis.

| Programme (country, year started) | Population | Age (years) | Treatment time (years) | Caseload | Interventions by area |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPPIC | People who have a first episode of psychosis | 12−25 | 2−5 | 15−20 patients per healthcare professional | Early detection |

| (Australia/1992) | People at high risk of having an episode of psychosis | • Community awareness-raising and education | |||

| • Easy access to health services | |||||

| • Home evaluation and home care | |||||

| Care during the acute phase | |||||

| • Access to hospitalisation care | |||||

| • Access to healthcare in the subacute phase | |||||

| Ongoing care | |||||

| • Case care | |||||

| • Medical interventions (antipsychotic drugs) | |||||

| • Psychological interventions | |||||

| • Functional recovery programme | |||||

| • Group programme | |||||

| • Family programme | |||||

| • Youth participation and peer support | |||||

| • Support for individual needs | |||||

| • Association with other institutions | |||||

| • Workforce development | |||||

| • Care for people at high risk of psychosis | |||||

| OPUS (Denmark, 1996) | People with a first episode of psychosis (schizophrenia spectrum disorders according to ICD-10 criteria). Patients must not have received ongoing antipsychotic medication for more than 12 weeks | 18-45 | 2 | 10 patients per healthcare professional | Assertive community treatment |

| • Assertive and support programmes | |||||

| • Personalised antipsychotic medication | |||||

| Family participation | |||||

| • Group family meetings | |||||

| • Individual family meetings | |||||

| • Workshops on survival skills with family and friends | |||||

| Training in social skills | |||||

| • Group work with 6−8 participants | |||||

| • Individual work with the patient | |||||

| RAISE (United States, 2008) | People with a first episode of psychosis (schizophrenia spectrum disorders) | 15−35 | 2 | 25 patients per team of 4 healthcare professionals | Individual medication management |

| Patients may or may not have received antipsychotic medication. Duration of symptoms not taken into account | • Reducing symptoms and minimising adverse effects and outcomes | ||||

| Family psychoeducation | |||||

| • Establishing collaborative relationships between family members and the healthcare team. Teaching family members about psychosis and its treatment. Reducing family stress. | |||||

| Individual therapy in resilience | |||||

| • Helping participants achieve functional recovery goals | |||||

| • Processing the experience of the psychotic episode | |||||

| Education and employment support | |||||

| • Getting and keeping competitive jobs | |||||

| • Receiving regular education and earning desired academic degrees |

ICD-10: International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition.

This programme was one of the first early intervention programmes in the world.16 Its objective is to reduce the time between the onset of psychotic symptoms and the start of treatment and to provide early symptomatic and functional recovery.16,18 The programme offers services of early detection, acute care during and immediately after a crisis and ongoing care aimed at recovery.18 The principles of the programme are: easy access to professional care, clinical interventions with a biopsychosocial and collaborative approach, comprehensive and specialised services, and a high level of association with local health providers to ensure timely and effective care.18 The programme consists of 16 components that seek to meet the health needs of patients and their families. Its design enables people to keep or return to their academic, occupational and social pursuits in the critical two to five years following the onset of the disease.18 EPPIC is currently part of the Orygen Youth Health programme, which uses the model of early intervention in psychosis to care for other serious mental illnesses.17 The programme has served as a model for the establishment of new programmes for early intervention in Europe, the United Kingdom, Asia and the United States.17

OPUS studyOPUS is not an acronym; rather, it is a word from the field of music and refers to an artistic work. This name was chosen to convey the notion of different instruments played together according to a plan and organised by a conductor.33 Analogously, the programme aspires to integrate psychiatric, psychological and social interventions in order to achieve prompt recovery in patients who report a first episode of psychosis.33 The OPUS project was preceded by recognition on the part of the health authorities of the difficulties around care in the initial stages of psychosis and their consequences for individuals, families and society. The core elements of the programme are assertive community treatment, family participation and training in social skills.33,36 Each of these strategies has been modified in order to adapt it to the needs of participants and families. The project began in the mental health departments in Copenhagen County and Aarthus County in Denmark, led by researchers at the universities in those localities. At present, the programme is considered the largest project in the field of psychiatry implemented in Denmark and is operating throughout the country.33

Recovery after an initial schizophrenia episodeThis programme was implemented by the United States National Institute of Mental Health to improve the prognosis and long-term course of schizophrenia through early interventions.37 Part of this programme is the NAVIGATE project, which seeks to guide people with a first episode of psychosis towards psychological and functional health through access to mental health services.34 The programme operates at community mental health centres that care for large numbers of patients with serious mental illnesses. It includes educational interventions for families, training in resilience, training in education and employment, and personalised medical treatment.34 The programme, which involves a multidisciplinary healthcare team, adopts a shared decision-making approach with patients and their families in preparing a treatment plan according to the patient's objectives and needs. Healthcare team members meet weekly to evaluate patients' progress, stressors and setbacks and propose solutions to their problems. At present, the programme is part of the United States mental health system and provides medical care to people with initial symptoms of psychosis.34

Programmes for early intervention in psychosis, compared to standard care, are more effective at reducing positive and negative symptoms,38,41 mitigating substance abuse,42 and improving social functioning39,41 and quality of life,40 as well as reducing hospitalisations and days of hospitalization.43,44 They are also more effective at reducing the burden of the disease on the family and improving satisfaction with treatment.44 In terms of costs, most studies have indicated that these programmes are more cost-effective than standard care,43,45 and studies indicating that these programmes are more costly have indicated that the clinical benefits achieved justify the higher levels of expenditure.46 The two-year duration of the programme is under debate, as outcomes have not been seen to be maintained following the patient's transition to standard care.47 Therefore, it has been suggested that a duration of two years is very short and the optimum duration of the programme should be further studied.19,32 It is generally agreed that programmes for early intervention in psychosis are effective and cost-effective because they have clinical and functional benefits for patients.19

Schizophrenia in PeruPeru, with a total of 30,475,000 inhabitants, is the fifth most populous country in Latin America, after Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Argentina.48 Its capital and biggest city is Lima, which has 9,541,000 inhabitants and a population density of 274.2 inhabitants per square kilometre.

The population of those 15–29 years of age has surpassed 8,283,000 inhabitants and accounts for 27.2% of the country's total population. Total health expenditure represents 4.62% of Peru's gross domestic product, and government expenditure in health amounts to $184 per capita.49 In 2011, the budget allocated to mental health was 0.27% of the total budget assigned to the health sector.49 Care for mental health problems was concentrated in three specialised hospitals in Lima, which received 98% of the budget.49 However, this situation is changing with the opening of community mental health centres in different regions of the country. Mental health care in Peru is currently governed by Law No. 29889, approval of which by the Congress of Peru in June 2012 initiated the mental health reform process. This law ensures healthcare for people with mental illnesses and makes a number of changes to the mental health system.25

The national prevalence of mental illnesses is unknown; information is only available for Lima and some other cities on the coast, in the mountains and in the jungle. Studies conducted in Lima have shown that 26.1% of the population has suffered from a mental illness at some point in their lives and that psychotic disorders have a lifetime prevalence of 1.5%, with this figure being similar between males and females.50 Although the severity of the disorder does not differ from that reported in other countries, schizophrenia in Peru is associated with a great deal of disability.51 Psychiatric diseases in Peru, including schizophrenia, account for 12% of the overall disease burden measured in terms of healthy life years lost. Schizophrenia specifically ranks twelfth among the diseases that account for the largest shares of the country's disease burden, ahead of diseases that receive more attention from the health authorities, such as tuberculosis, which ranks seventeenth, and iron deficiency anaemia, which ranks twenty-second.51 Therefore, rapid recovery of patients with schizophrenia is important not only from a health perspective, but also from a socioeconomic point of view.

In Peru, many factors may have a negative impact on the severity and prognosis of schizophrenia. First, more than a quarter of the Peruvian population is in the 15–29 age group,48 coinciding with the period marked by the highest vulnerability to developing schizophrenia, i.e. 16–30 years of age.52 This means that, considering age alone, a high number of citizens is at risk of suffering from this disorder. Second, access to mental health services for this disorder is limited; it has been found that just 12.7% of people who have experienced an episode of psychosis in the past year sought medical care in that period.50 It is hoped that access to mental health services will improve in the next few years with the opening of community mental health centres in different regions of the country.26 Third, in Peru, schizophrenia carries a great deal of stigma, and those with the disease face much discrimination, such that the disorder is often associated with violence and negative incidents.50 Finally, Peru is going through an epidemiological transition with a resulting increase in chronic diseases.53 This situation adds a layer to the risk of developing metabolic disorders already imposed by the disease itself and its treatment.54,55

Implementation of a programme for early intervention in psychosis in PeruMental health and treatment of mental illnesses have received little attention from the Peruvian health authorities. This situation was reflected in the modest budget allocated to the sector, limited access to mental health services and short supply of mental health professionals, especially in regions outside of Lima. This has been changing in recent years, first as a result of recognition on the part of the authorities that mental health is a component of human well-being and, second, due to solid changes made to the health system as part of mental health reform.25 At present, community mental health centres are being established in different regions of the country, incorporated into primary care26; numbers of places at universities for training mental health professionals have been increased; and Seguro Integral de Salud [Comprehensive Health Insurance], i.e. Peruvian national health insurance, provides full coverage for the diagnosis and treatment of mental illnesses.24,25 These changes show that the country is in a suitable position to implement effective and cost-effective interventions that improve the health of people with mental illnesses.

Mental health reform does not explicitly call for opening programmes for early intervention in psychosis as part of this process. However, the principles of reform are consistent with these programmes. For reform to occur, people with mental illnesses must have access to more effective and timely treatment.25 Programmes for early intervention in psychosis have proven more effective than standard care and also fulfil the timely criterion, given that they are applied early in the course of the disease.19 Reform also requires that patients receive rehabilitation as well as family, occupational and community reintegration.25 Programmes for early intervention are aimed not only at clinical recovery, but also at restoring a person's functioning, meaning that each of these elements is considered in a comprehensive approach.16,33,34 Reform seeks to provide community outpatient care for mental health problems.25 This criterion is aligned with programmes for early intervention in psychosis, since healthcare is provided in community centres.33,34 Thus, the structure and characteristics of programmes for early intervention in psychosis comply with mental health reform guidelines.

Implementation of a programme for early intervention in psychosis in Peru could have a number of benefits for patients who present with this condition. The current mental health system in Peru does not address preventive strategies in mental health care. This programme would enable work on secondary prevention of schizophrenia through early detection and timely treatment of cases. The Peruvian population holds religious and folkloric beliefs that lead to discrimination against and stigmatisation of those with mental illnesses.56 The programmes include psychoeducation strategies aimed at patients and their families that seek to break down myths and address feelings of guilt and shame which negatively influence patient health.16,33,34 People with psychotic symptoms are often unemployed,57 have abandoned their studies,58 have limited social relationships59 and suffer from suicidal ideation in the early stages of the disorder.60 These problems are addressed in the programme, and an assertive approach is used to tackle problems in daily life, employment, studies and development of social skills.16,33,34 Finally, schizophrenia has a better prognosis in middle- to low-income countries than in high-income countries.61 This factor in favour of Peru means that implementation of programmes for psychosis may yield favourable patient health outcomes.

Despite the favourable context and the potential benefits for patient health, implementation of a programme for early intervention in psychosis does entail a number of challenges. The main challenge is raising awareness among mental health decision makers of the differentiated healthcare needs of patients with initial psychotic symptoms, and of the efficacy that supports the implementation of these programmes. A second challenge is resistance by healthcare professionals to acquiring and applying new care models.62 Programmes for early intervention operate from a different perspective than standard care, especially in relation to the assertive approach and shared decision-making between the professional and the patient. This different approach requires personnel to acquire new occupational skills. A positive predisposition is required to modify previously learned skills. A third challenge lies in preserving the reliability of and evidence for a programme so that it may produce the desired effects against a backdrop of frequent changes to health programmes by the authorities.63

Implementation of a programme for early intervention in psychosis in Peru must be gradual. The programme should start at specialised mental health centres, given that these institutions have resources and care workflows for patients with psychosis. Community mental health services are in a developmental stage and, therefore, do not constitute a favourable setting for implementing these programmes. The healthcare team should develop skills and incorporate knowledge enabling them to treat patients with a first episode of psychosis; therefore, they should continuously train in the therapy, psychological care and other strategies used in the programme. A care protocol should be prepared based on programmes in other countries, but adapted to local health needs. This document should specify the programme's components, phases, structure and strategies, and it should be adhered to with a high degree of fidelity. Programme outcomes should be evaluated not only by clinical indicators but also by family and social indicators. Once capacities are developed in the care of people with a first episode of psychosis at specialised institutions and the benefits of the intervention are confirmed, the resources and capacities learned should be disseminated to community mental health centres in a gradual, coordinated manner.

ConclusionsProgrammes for early intervention in psychosis offer coordinated and comprehensive treatment to patients with initial symptoms of psychosis. These programmes have proven more effective than standard care at improving the symptoms of the disorder and improving patient functioning. Furthermore, they are more cost-effective. These programmes have been gradually implemented in high-income countries, whereas in middle- to low-income countries their development has been slower. Peru is going through a reform of its mental health system that offers an opportunity to implement these programmes, the characteristics and objectives of which are aligned with the principles of the reform effort. This programme should be gradually implemented through raising awareness among the health authorities of the importance of investing in prevention, developing skills in healthcare professionals and preparing a care protocol suited to actual population needs. Once capacities are developed on a local scale, human and logistical resources are acquired and awareness is raised among healthcare professionals of the importance of preventive efforts, dissemination of the programme to community mental health centres in a gradual, coordinated manner can be considered.

Conflicts of interestNone.

We would like to thank Dr Lizardo Cruzado Díaz and Dr Santiago Stucchi Portocarrero for critically reviewing the study.

Please cite this article as: Valle R. Revisión de los programas de intervención temprana de psicosis: propuesta de implementación en Perú. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:178–186.