Diagnostic classification systems categorise mental psychopathology in mental disorders. Although these entities are clinical constructs developed by consensus, it has been pointed out that in practice they are usually managed as natural entities and without evaluating aspects related to their nosological construction. The objectives of the study are to review a) the conceptualisation of mental disorders, b) the indicators of validity, reliability and clinical utility, and c) the values of these indicators in ICD-11 schizophrenia. The results show that mental disorders are conceptualised as discrete entities, like the diseases of other areas of medicine; however, differences are observed between these diagnostic categories in clinical practice. The reliability and clinical utility of mental disorders are adequate; however, the validity is not yet clarified. Similarly, ICD-11 schizophrenia demonstrates adequate reliability and clinical utility, but its validity remains uncertain. The conceptualisation of psychopathology in discrete entities may be inadequate for its study, therefore dimensional and mixed models have been proposed. The indicators of validity, reliability and clinical utility enable us to obtain an accurate view of the nosological state of mental disorders when evaluating different aspects of their nosological construction.

Los sistemas de clasificación diagnóstica categorizan la psicopatología en trastornos mentales. Aunque estas entidades son constructos clínicos elaborados por consenso, se ha señalado que en la práctica se suele tratarlas como entidades naturales y sin valorar aspectos relacionados con su construcción nosológica. Los objetivos del estudio son revisar: a) la conceptualización de los trastornos mentales; b) los indicadores de validez, confiabilidad y utilidad clínica, y c) los valores de estos indicadores en la esquizofrenia de la CIE-11. Los resultados muestran que los trastornos mentales están conceptualizados como entidades discretas, al igual que las enfermedades de otras áreas de la medicina; sin embargo, se observan diferencias entre ambas categorías diagnósticas en la práctica clínica. La confiabilidad y la utilidad clínica de los trastornos mentales son adecuadas; no obstante, la validez aún no está esclarecida. De modo similar, la esquizofrenia de la CIE-11 presenta adecuadas confiabilidad y utilidad clínica, pero su validez permanece incierta. La conceptualización de la psicopatología mental en entidades discretas puede resultar inadecuada para su estudio, por lo que se han propuesto modelos dimensionales y mixtos. Los indicadores de validez, confiabilidad y utilidad clínica permiten tener una visión precisa del estado nosológico de los trastornos mentales al valorar distintos aspectos de su construcción nosológica.

The concept of disease operates on the assumption that diseases are conditions of bodily aetiology that cause pathological abnormalities and result in signs and symptoms.1 This approach applied to psychiatry functions according to the same principles and assumes that mental symptoms are caused by abnormalities in the brain.1–3 Although this assumption has not been confirmed,4–6 the application of the concept of disease to psychiatry has proven favourable, as it enables psychiatric diagnoses to be made and mental symptoms to be treated.7,8 This has been achieved primarily with the conceptualisation of psychopathology as discrete entities termed mental disorders,9 which are not natural entities4 but clinical constructs that group signs and symptoms by consensus.10,11 The conceptualisation of mental disorders defines the content and characteristics of these entities12,13 and may vary with the publication of each new diagnostic classification system (the International Classification of Diseases [ICD]14 and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual [DSM]15).16–20

The conceptualisation of schizophrenia, to cite an example, has varied with the publication of each new version of the ICD and the DSM.21–23 The diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia have undergone changes that have broadened or narrowed the conceptual construct of this entity.21,24 These changes have arisen primarily from a lack of agreement on the definition of the disorder,9,13 the variety of theories that seek to explain its essential nature1 and the new evidence arising from publications of classification systems.25,26 The ICD-11, for example, reflected changes to the ICD-10 conceptualisation of schizophrenia that included the removal of Schneider's first-rank symptoms, given the studies showing their limited specificity in schizophrenia,27,28 and changes to specifiers (severity of symptoms and course) to improve the description of the disorder.29,30 The ICD-11 construct of schizophrenia will remain current for use in clinical practice, public health and research until new findings demand changes to it.31

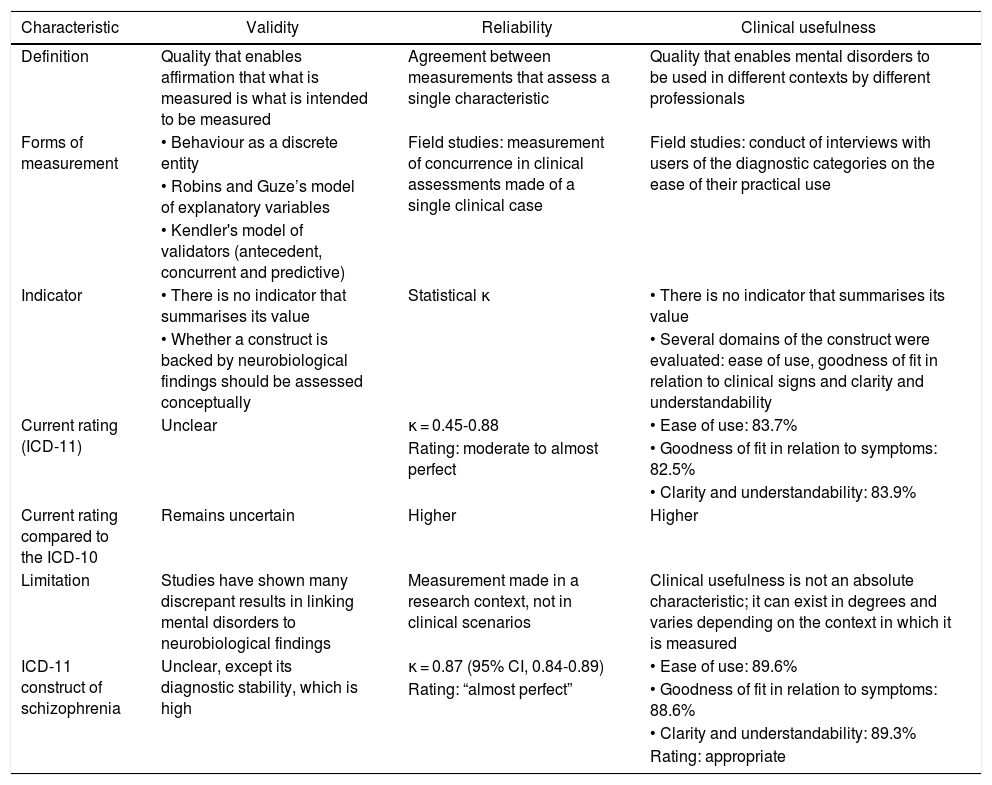

The conceptualisation of mental disorders is evaluated using indicators of validity, reliability and clinical usefulness (Table 1).1,32 Validity assesses the correspondence of the disorder as a true mental illness, reliability evaluates agreement in diagnosis across different evaluations and clinical usefulness considers the practical use of these entities in different contexts.32–34 These indicators vary across mental disorders and within a single mental disorder depending on the version of the classification system. In addition, changes in the conceptualisation of a disorder modify these indicators, and many changes are made to modify the value of one of them. For example, the DSM-III sought to improve reliability, and therefore incorporated explicit diagnostic criteria into clinical constructs.35 The ICD-11 sought to improve clinical usefulness, and therefore employed criteria for usefulness in the conceptualisation of disorders.36–38 Validity, for its part, is the indicator that has received the least attention, and both the ICD and the DSM have yet to study it in a comprehensive manner.39,40

Definition and characteristics of validity, reliability and clinical usefulness.

| Characteristic | Validity | Reliability | Clinical usefulness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definition | Quality that enables affirmation that what is measured is what is intended to be measured | Agreement between measurements that assess a single characteristic | Quality that enables mental disorders to be used in different contexts by different professionals |

| Forms of measurement | • Behaviour as a discrete entity | Field studies: measurement of concurrence in clinical assessments made of a single clinical case | Field studies: conduct of interviews with users of the diagnostic categories on the ease of their practical use |

| • Robins and Guze’s model of explanatory variables | |||

| • Kendler's model of validators (antecedent, concurrent and predictive) | |||

| Indicator | • There is no indicator that summarises its value | Statistical κ | • There is no indicator that summarises its value |

| • Whether a construct is backed by neurobiological findings should be assessed conceptually | • Several domains of the construct were evaluated: ease of use, goodness of fit in relation to clinical signs and clarity and understandability | ||

| Current rating (ICD-11) | Unclear | κ = 0.45-0.88 | • Ease of use: 83.7% |

| Rating: moderate to almost perfect | • Goodness of fit in relation to symptoms: 82.5% | ||

| • Clarity and understandability: 83.9% | |||

| Current rating compared to the ICD-10 | Remains uncertain | Higher | Higher |

| Limitation | Studies have shown many discrepant results in linking mental disorders to neurobiological findings | Measurement made in a research context, not in clinical scenarios | Clinical usefulness is not an absolute characteristic; it can exist in degrees and varies depending on the context in which it is measured |

| ICD-11 construct of schizophrenia | Unclear, except its diagnostic stability, which is high | κ = 0.87 (95% CI, 0.84-0.89) | • Ease of use: 89.6% |

| Rating: “almost perfect” | • Goodness of fit in relation to symptoms: 88.6% | ||

| • Clarity and understandability: 89.3% | |||

| Rating: appropriate |

The concept of disease applied to psychiatry has proven useful.1 However, problems with its practical application have been detected. Studies have shown that, although mental disorders are clinical constructs,4 their inclusion in official diagnostic classification systems may result in their reification.32,41,42 With this, these entities are treated as natural entities, and matters related to their conceptualisation cease to be assessed.43,44 In addition, although the indicators of validity, reliability and clinical usefulness assess different aspects of mental disorders, in practice they are used interchangeably, leading to errant assessment of these entities in which properties that they do not possess are attributed to them.39 The objective of this study was to review: a) the conceptualisation of mental disorders; b) the concepts of validity, reliability and clinical usefulness; and c) the values of these indicators in the ICD-11 conceptualisation of schizophrenia. This disorder was selected because this entity’s construct sparks more discussion with each newly published diagnostic classification system.1,22

Conceptualisation of mental disordersDiagnostic classification systems, based on the concept of disease, conceptualise the heterogeneity of psychopathology as mental disorders. The ICD-10 defined these entities as “a clinically recognizable set of symptoms or behaviours associated in most cases with distress and with interference with personal functions”.14 The DSM-5, for its part, defined a mental disorder as a “syndrome characterized by clinically significant disturbance in an individual's cognition, emotion regulation, or behavior that reflects a dysfunction in the psychological, biological, or development processes underlying mental functioning. Mental disorders are usually associated with significant distress or disability in social, occupational, or other important activities”.15 In that sense, a mental disorder is currently the nosological entity that individualises psychopathology through symptoms, abnormal behaviours and loss of functioning.

The conceptualisation of mental disorders defines the content, characteristics and scope of pathological expression for use in clinical practice, public health and research.15 This process establishes the boundaries of what is classified, assigns a condition to the field of psychiatry or another medical specialisation, decides whether related diseases are grouped or split and sets the threshold that distinguishes the pathological from the non-pathological.12 The latest versions of the classification systems, specifically the DSM-III (1980) and later versions thereof, conceptualised mental disorders with diagnostic criteria and specifiers.32 Diagnostic criteria consist of clinical signs operationalised by their frequency and severity that, guided by clinical judgement, allow a psychiatric diagnosis to be made.15 Specifiers, on the other hand, are used once a diagnosis has been made, and allow the disorder to be characterised according to its course, its seriousness and the characteristics of its presentation.15

Mental disorders are conceptualised as discrete entities in the same manner as diseases in other branches of medicine.41 This approach considers mental disorders to be independent entities, with their own pathophysiology and with a well-established correlation between symptoms, course and clinical outcome.45 It also assumes the existence of a “zone of rarity” between different mental disorders.39 This approach is used in the conceptualisation of these entities even when they have demonstrated no such quality, and when diagnostic classification systems have explicitly stated that there is no evidence that mental disorders are discrete entities.46 Therefore, while mental disorders are conceptualised as discrete entities in the current versions of the ICD and the DSM, and are used as such in contemporary clinical practice and research in psychiatry, this does not mean that psychopathology definitively possesses such a quality.44

Despite being conceptualised as discrete entities, mental disorders have certain differences from diseases in other areas of medicine.47 These differences are evident when these entities are applied in the study of their respective diseases. In other medical specialisations, symptoms are closely correlated with anatomical abnormalities or laboratory tests, entities are clearly defined as a disease or a syndrome, and there is a clear delimitation between diseases.32 In psychiatry, however, mental symptoms do not show a stable correlation with genetic, anatomical or neurochemical abnormalities;48 many mental disorders present ambiguous states, whether as an isolated symptom, a disease or a syndrome;39 and a variety of these entities vaguely overlap with other entities or even normality.5,49 Lately, the differences between these diagnostic categories have made it clear that it is inappropriate to conceptualise psychopathology as discrete entities.50

Validity of mental disordersValidity refers to the approximate truth or falsehood of scientific proposals.33 In science, there is no agreement on the concept of validity, but it is accepted that it is not only a problem of measurement, but also an epistemological or philosophical problem dealing with the nature of reality.39 It has been said that the most appropriate definition of validity can be epitomised with the question: are we measuring what we think we are measuring?51 That is to say, validity would refer to the property of the instrument that enables affirmation that what is being measured really is what is intended to be measured.52 Carrying this concept over to the field of psychiatry, the validity of mental disorders would correspond to the possibility of these entities irrefutably describing true mental illnesses. Validity in mental disorders has been the subject of little debate; the few studies that have addressed it have indicated that validity in mental disorders is unclear39,53 and will not become clear by simply redefining existing criteria for disorders or adding new disorders.42

Validity lacks a simple measure that can sum up its value.32 Validity in mental disorders can be demonstrated when mental disorders are shown to be discrete entities or entities associated with explanatory variables.5,39 Discrete entities, discussed above, should have a specific correlation between pathophysiology, clinical signs, clinical course and outcome, as well as clear, well-established boundaries that distinguish them from other diseases.45 Mental disorders show no such characteristics; on the contrary, their pathophysiology remains unknown (while some markers associated with their development have been discovered, none has demonstrated a consistent relationship), and their symptoms are non-specific (poor pathognomonic symptoms) and weakly associated with diagnoses. Therefore, mental disorders present as vague, puzzling entities and their boundaries are not firmly established, which has led to the development of large numbers of comorbidities.53 In that sense, mental disorders do not show characteristics of discrete entities, and therefore their validity cannot be established using this model.5

Various authors have proposed a set of explanatory variables to which mental disorders should be related for purposes of demonstrating their validity.5,39 Robins et al.54 (1970) cited clinical description, laboratory tests, processes of ruling out other disorders, follow-up studies and family studies as explanatory variables. Kendler classified explanatory variables as antecedent validators (familial aggregation, precipitating factors and premorbid personality), concurrent validators (psychological tests) or predictive validators (diagnostic stability, relapse and recovery rate, and response to treatment).55,56 The DSM-5 proposed the following as explanatory variables: neural substrates, familial traits, genetic risk factors, environmental risk factors, biomarkers, symptoms, temperamental history, abnormalities in emotional and cognitive processing, similarity of symptoms, disease course, high comorbidity and response to treatment.15 According to this model, the stronger the associations that a mental disorder shows with these variables, the more likely that mental disorder is to possess validity.33

At present, the most direct measure of validity is diagnostic stability.57 This variable measures just one aspect of validity (predictive validator): whether a disease is consistently diagnosed within a single diagnostic category. The indicator is represented by the percentage of patients with a single diagnosis over time. This variable assumes that the more stable a mental disorder is, the more likely it is to genuinely reflect an abnormality in a neuroanatomical substrate that enables prediction of its course, response to treatment and prognosis.58 By contrast, low diagnostic stability indicates that the conceptualisation of the disorder is very likely not based on solid aetiopathogenic variables.59 Diagnostic stability has significant implications for clinical practice and research in psychiatry, because it may lead to poor decision-making with respect to diagnosis and treatment and to biased research results in studies of risk factors, familial aggregation and prognosis.60

Reliability of mental disordersReliability refers to agreement between two measurements that assess a single characteristic.61 Intra-rater reliability refers to agreement between repeat measurements made by a single rater. Interobserver reliability corresponds to the agreement of a single measurement made by different raters.62 Before 1980, psychiatry practice was hindered by low reliability in mental disorders.9,32 Thus, agreement in psychiatric diagnosis was quite poor, and terms such as schizophrenia were used differently in different countries, and even at different centres in the same country.9 The problem of low reliability was addressed by the DSM-III, which incorporated standardised diagnostic criteria into the conceptualisation of mental disorders.35 This change improved the reliability of these diagnostic categories, and therefore communication between clinicians and researchers.5 Due to these results, the subsequent versions of the diagnostic classification systems definitively adopted this approach.32

The reliability of mental disorders has improved with each newly published classification system.63 This indicator, unlike validity and clinical usefulness, can be evaluated with a single summary measure called a kappa (κ) statistic.64 This indicator evaluates agreement between evaluations; the closer the value to 1, the better the reliability.64 World Health Organization (WHO) field research for the study of the mental disorders proposed by the ICD-11 has shown concurrent inter-rater reliability to range from κ = 0.45 for dysthymic disorder to κ = 0.88 for social anxiety disorder.63 These values indicate reliability values ranging from moderate to almost perfect and higher than those of their equivalent diagnostic categories in the ICD-10.63,65 However, this improvement in reliability has only been demonstrated in research contexts, where diagnostic criteria can be used operationally; there is no evidence of a corresponding improvement in clinical scenarios.36

The high reliability achieved in mental disorders does not correlate with improvements in their validity.32 Indicators of validity and reliability (and even clinical usefulness) are inter-related, but not directly.63,66 For example, a mental disorder with demonstrable validity— i.e., one that has proven to be a discrete entity or to significantly correlate with explanatory variables — may lead to poor agreement in psychiatric diagnosis (low reliability).32 On the other hand, a mental disorder with high reliability may have uncertain validity; in such a situation, the entity's high reliability is of little value in psychiatry practice.32 Although improvement in reliability undoubtedly signalled progress in diagnosis and communication in psychiatry, the diagnostic process suffered losses in sophistication and specificity.53 In that sense, research has indicated that classification systems, in offering high reliability but low validity, have yielded psychiatry nomenclature that is shared but probably incorrect.53

Clinical usefulness of mental disordersThe clinical usefulness indicator measures characteristics of mental disorders such as their scope, capacity for describing a clinical condition and ease of use in various situations.32 The WHO has stated that a diagnostic category is useful if it promotes communication among users, facilitates conceptualisation and understanding of diagnostic entities, can be readily implemented in different contexts, and aids in selecting treatments and taking a suitable approach to clinical entities.10 It has been stated that mental disorders should be clinically useful by necessity, and that their practical application should not be complicated, since otherwise healthcare professionals could use these categories inappropriately, which would have negative repercussions for psychiatry practice.34 The latest versions of the ICD and the DSM were designed with the main objective of improving the clinical usefulness of mental disorders, because that is crucial for meeting the WHO's goal of reducing the disease burden of psychiatric entities.36,67

The WHO has evaluated the clinical usefulness of mental disorders within a systematic field study programme.67 The studies were conducted in a training phase that encompassed international surveys and training studies, and in an evaluation phase in which case–control and ecological studies were conducted.36,67 The different methods used, the variety of professionals who participated and the different languages in which the studies were conducted covered all aspects of the construct of clinical usefulness.67 The results of one of these studies in a sample of 339 healthcare professionals from 13 countries showed that, in general, participants positively rated the indicators of clinical usefulness of the diagnoses proposed in the ICD-11. Mental disorders received a rating of “quite” or “extremely” in the categories “ease of use” (83.7%), “goodness of fit or accuracy” in relation to patients’ clinical signs (82.5%) and “clarity and understandability” (83.9%).34 In addition, the diagnostic categories in the ICD-11 have received better scores on indicators of clinical usefulness than their respective categories in the ICD-10.68

Validity and clinical usefulness, despite being different concepts, are often used synonymously.39 Whereas validity is an invariable and absolute quality of a diagnostic category (mental disorders are valid or not), clinical usefulness can exist in degrees and varies depending on the context.5,39 For example, although schizophrenia has not been shown to be a valid concept, its construct is highly useful in clinical practice but of limited usefulness in genetic studies.39 In addition, different definitions of a single diagnostic entity have different effects on these indicators. The validity of a disorder becomes debatable there is more than one definition of its construct (schizophrenia in the ICD and the DSM); however, clinical usefulness benefits from there being different definitions, as in genetic studies of psychosis, in which it is preferable to use a broad category such as “schizophrenic spectrum disorder” versus a more limited category such as “schizophrenia” alone. It is important to distinguish between validity and clinical usefulness, since otherwise mental disorders could be considered valid entities when they are merely useful constructs.5

Validity, reliability and clinical usefulness of ICD-11 schizophreniaDiagnostic classification systems conceptualise schizophrenia as a discrete entity. This disorder is described with a set of clinical criteria defined by characteristics, duration and form of presentation,14,15,69 and people who met these criteria receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia (probabilistic diagnosis).1 This approach has enabled clinical treatment and research in chronic psychotic diseases. However, it has also shown that psychotic conditions, conceptualised in the construct of schizophrenia, lack the characteristics of a discrete entity. This is reflected in the high rate of comorbidity of schizophrenia with other mental disorders (e.g., obsessive–compulsive disorder), problems with classifying cases with psychosis and mood disturbances (e.g., schizoaffective disorder) and problems with classifying subthreshold psychotic conditions (e.g., attenuated psychosis syndrome).39,70,71 In that sense, although schizophrenia is conceptualised as a discrete entity, psychotic disease does not seem to possess this characteristic.

The validity of schizophrenia evaluated in terms of its correlation with explanatory variables has also not been demonstrated.21 Kraepelin, the first to conceptualise the construct of dementia praecox (later designated “schizophrenia”),50,72 believed that this disorder could be validated by means of neuropathology findings. He therefore conducted a number of studies with the most distinguished neuropathologists of his time; nevertheless, the results of his studies were inconclusive and he had to validate the disorder based on its symptoms, course and outcome.73 A century later, studies on neuroanatomy, neurochemistry and genetics have approached the study of schizophrenia with the objective of finding biological markers that could explain its pathogenesis.74–76 These studies also have not shown consistent results;48,77 on the contrary, they have indicated that multiple aetiological factors and different pathophysiological mechanisms may lead to this disorder.78. These results have spurred a current trend towards considering schizophrenia to be an entity that groups a set of specific diseases that today are difficult to individualise.22,23

The diagnostic stability of schizophrenia, evaluated as an aspect of validity, has been shown to be appropriate.63 Schizophrenia has high diagnostic sensitivity, and more than 90% of patients diagnosed with schizophrenia maintain their diagnoses after two and five years.79–81 The diagnostic stability of schizophrenia in the DSM-5 has not been evaluated, but probably retains the same value, given the minimal differences in the conceptualisation of the disorder between the DSM-5 and the DSM-IV-TR.25 The diagnostic stability of schizophrenia evaluated in patients with a first episode of psychosis has also been shown to be appropriate. A meta-analysis of a sample of 14,484 patients followed up for an average of 4.5 years found the diagnostic stability of this disorder to be 0.90 (95% confidence interval [95% CI] 0.85–0.95).82 These results are comparable to the diagnostic stability values of diseases such as dementia, which has a stability of 0.91.83 Therefore, the diagnostic stability of schizophrenia is the only aspect of validity that shows appropriate values at present.

The reliability of ICD-11 schizophrenia has been classified as appropriate. The ICD-10 evaluated the reliability of this disorder in a study at 112 sites in 39 countries before the manual was published.65 The study used a “case conference” methodology, in which a rater interviewed a patient and then the interview was presented to other raters for them to make a diagnosis, whereupon inter-rater reliability could be calculated. The reliability found was κ = 0.81, which was classified as “very good”.65 The ICD-11, recognising the potential biases of the methodology used in the ICD-10, calculated concurrent inter-rater reliability, which consisted of two clinicians evaluating a single patient at the same time. The reliability found was κ = 0.87 (bootstrapped, 95% CI 0.84–0.89), classified as “almost perfect”, placing schizophrenia among the disorders with the highest degrees of reliability in the ICD-11.63 Based on this result, it has been concluded that the proposal for the diagnosis of schizophrenia in the ICD-11 is appropriate for universal application.63

The ICD-11 construct of schizophrenia has demonstrated appropriate clinical usefulness in WHO training and evaluation studies.34,36,67 One of these studies evaluated the clinical usefulness of schizophrenia and other psychiatric disorders in a sample of 339 healthcare professionals from 13 countries with different languages and cultures.34 The results show that the participants rated the ICD-11 clinical construct of schizophrenia “quite” or “extremely” in the categories “ease of use” (89.6%), “goodness of fit” in relation to the patient's clinical signs (88.6%) and “clarity and understandability” (89.3%). These values were higher than those received by recurrent or single-episode depressive disorder with the same rating (“quite” or “extremely”) in each of the corresponding categories.34 In light of the available information, it is observed that the clinical usefulness of the current ICD-11 construct of schizophrenia is perceived to be positive among healthcare professionals, regardless of their training, culture or language.

DiscussionThe concept of disease in psychiatry has enabled the conceptualisation of the heterogeneity of mental psychopathology as nosological units called mental disorders. This approach has proven useful to psychiatry as it allows diagnoses to be made, evaluations to be performed, treatments to be applied and prognoses to be postulated.7,8 However, it has not enabled the underlying causes of mental illness to be determined.84 In addition, the approach (discrete entity) in which the concept of disease conceptualises mental disorders might suggest that mental disorders are “quasi-diseases” whose only aspect up for debate is their unknown aetiology,33,45 and ignore matters related to their nosological construction, such as the grouping of symptoms based on a criterion of concurrence and changes guided by specific objectives to be reached. Recognising these latter two aspects is crucial to understanding the true nosological status of mental disorders; failing to appreciate them, on the other hand, feeds the notion that they are natural entities.

Given the inconsistencies shown by the conceptualisation of psychopathology as discrete entities, it has been proposed that mental symptoms be studied according to a dimensional approach.85,86 This approach assumes quantitative variation and a gradual transition between the various mental disorders and between “normality” and a disorder.41 A dimensional approach overcomes the weaknesses of studying mental symptoms as discrete entities in relation to the study of traits (e.g., personality and personality disorders), psychiatric comorbidities and subthreshold clinical conditions.41 One example of the use of this approach is found in the Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) project, developed by the United States National Institute of Mental Health, which seeks new ways of classifying mental disorders based on dimensions of observable behaviour and neurobiological findings.87–89 A dimensional approach is not exclusive of discrete entities; hence, mixed and hybrid models combining qualitative categories with measurements of quantitative traits have been formulated.41,90,91

Indicators of validity, reliability and clinical usefulness offer insight into different aspects of mental disorders. Understanding these indicators may aid in having a true, empirical view of the current nosological status of mental disorders for two reasons. First, these indicators provide relative empirical assessments on an aspect of these diagnostic entities, shedding light on the strengths and weaknesses of each of them. Thus, these indicators ground the true state of mental disorders in facts, which helps to dispense with the typical notion that these diagnostic categories correspond to natural entities. Second, these indicators also provide information on the effects of changes in the conceptualisation of mental disorders. Therefore, the developers of diagnostic classification systems can measure the consequences of changing, adding or removing diagnostic criteria corresponding to the clinical constructs of these entities using well-defined indicators.

Assessment of the validity, reliability and clinical usefulness of schizophrenia enables measurement of the different qualities of its construct. ICD-11 schizophrenia has proven useful in the clinical treatment of chronic psychotic disease and shows high reliability derived from high levels of agreement on diagnosis. However, despite these improvements, the validity of schizophrenia is unclear, since the disorder does not behave as a discrete entity (as it does not show itself to be an independent entity with clear boundaries distinguishing it from other conditions),39,45 nor is it consistently associated with explanatory variables indicating genetic anomalies or neurochemical, structural or functional abnormalities of the brain.74–76 The only matter to be highlighted in relation to its validity is diagnostic stability, which indicates the very low likelihood of this diagnosis being changed to another diagnostic category over time.79–81 The study of this disorder should be centred on improving its validity, since otherwise a diagnostic category will continue to be used in the absence of clarity or certainty as to what is being evaluated.

The findings of this study support the proposal to develop psychiatric nosology as a science.92 The variable nosological status of mental disorders and the different experiences and expressions of psychopathology across different cultures call for these entities to be systematically studied before they can be universally used. The epidemiological field studies conducted by the WHO prior to the publication of the ICD-11 are a sample of the empirical study with which these entities can be evaluated.37,63,66,67 However, it is still necessary to build a body of evidence on theories, methods and procedures for their standardised study. We find it important for this effort to first and foremost assess ontological aspects of psychopathy;93,94 to this should be added research meetings in the biological sciences (e.g., genetics, biochemistry, etc.) for the purpose of stressing natural and essential aspects of psychopathology, which has not yet been thoroughly elucidated by psychiatry.

This proposal must also assess the role of cultural considerations in the development of psychopathology. The scientific evidence has shown differences in the pathogenesis, expression and outcome of mental disorders depending on the cultural context.95–98 One example of this lies in the International Pilot Study of Schizophrenia, a WHO study in nine countries with different cultural backgrounds that found that although healthcare professionals used the same procedures in psychiatric diagnosis, the presentation and clinical outcomes of mental illness varied across developed and developing countries.99,100 We also believe that the needs for practical use of mental disorders should be considered secondary, since the principles of usefulness do not necessarily correlate with those of validity,5,39 which is the aspect of mental disorders that has yet to be clarified. Developing psychiatric nosology as a science represents a complex and challenging task, but a vital and necessary one for advancing psychiatry as a medical discipline.92

In conclusion, mental disorders are clinical constructs prepared as discrete entities that represent and individualise psychopathology. The current approach with which they are conceptualised appears to be inconsistent with the nature of mental illness; therefore, new models of study have been proposed. Mental disorders have appropriate reliability and clinical usefulness, but their validity remains unclear. The ICD-11 construct of schizophrenia is appropriate for diagnosis and clinically useful for treatment of chronic psychotic conditions; however, its validity has not been thoroughly elucidated. Knowledge of these indicators opens the door to a more accurate view of mental disorders and assessment of various aspects of their nosological construction. Future research in this field should centre on the study of the validity of mental disorders; otherwise, these categories will continue to be used without complete certainty as to what is being evaluated.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Valle R. Validez, confiabilidad y utilidad clínica de los trastornos mentales: el caso de la esquizofrenia de la CIE-11. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2022;51:61–70.