The COVID-19 pandemic has negatively impacted mental health. Up to a quarter of the population has reported mental health disorders. This has been studied mainly from a nosological perspective, according to diagnostic criteria. Nevertheless, we did not find studies that have explored the daily expressions of the population. Our objective was to evaluate the perceptions of the COVID-19 pandemic and its repercussions on the emotional well-being of the Colombian population.

MethodsWe performed a Twitter metrics and trend analysis. Initially, in the trend analysis, we calculated the average duration in hours of the 20 most popular trending topics of the day in Colombia and we grouped them into trends related to COVID-19 and unrelated trends. Subsequently, we identified dates of events associated with the pandemic relevant to the country, and they were related to the behaviour of the trends studied. Additionally, we did an exploratory analysis of these, selected the tweets with the greatest reach and categorised them in an inductive way to analyse them qualitatively.

ResultsIssues not related to COVID-19 were more far-reaching than those related to coronavirus. However, a rise in these issues was seen on some dates consistent with important events in Colombia. We found expressions of approval and disapproval, solidarity and accusation. Inductively, we identified categories of informative tweets, humour, fear, stigma and discrimination, politics and entities, citizen complaints, and self-care and optimism.

ConclusionsThe impact of the COVID-19 pandemic generates different reactions in the population, which increasingly have more tools to express themselves and know the opinions of others. Social networks play a fundamental role in the communication of the population, so this content could serve as a public health surveillance tool and a useful and accessible means of communication in the management of health crises.

La pandemia de COVID-19 ha impactado negativamente en la salud mental. Hasta un cuarto de la población ha reportado alteraciones de salud mental. Esto se ha estudiado principalmente desde una perspectiva nosológica según criterios diagnósticos; sin embargo, no encontramos estudios que hayan explorado las expresiones cotidianas de la población. Nuestro objetivo es evaluar las percepciones y repercusiones en el bienestar emocional de la población colombiana por la pandemia de COVID-19.

MétodosSe realizó un análisis de métricas y tendencias en Twitter. Inicialmente, en el análisis de tendencias se calculó el promedio de duración en horas de los 20 temas tendencia del día más populares en Colombia y las agrupamos en relacionadas con la COVID-19 y no relacionadas. Después se identificaron fechas de acontecimientos asociados con la pandemia relevantes para el país, y se relacionaron con el comportamiento de las tendencias estudiadas. Además, se hizo un análisis exploratorio de estas, se seleccionaron los tweets con mayor alcance y se categorizaron de forma inductiva para analizarlos cualitativamente.

ResultadosLos temas no relacionados con COVID-19 tuvieron mayor alcance que los relacionados con coronavirus. No obstante, se vio un alza de estos temas en algunas fechas concordantes con hechos importantes en Colombia. Se hallaron manifestaciones de aprobación y desaprobación, de solidaridad y de acusación. De manera inductiva, se identificaron categorías de tweets informativos, humor, miedo, estigma y discriminación, política y entidades, denuncia ciudadana, y autocuidado y optimismo.

ConclusionesEl impacto de la pandemia de COVID-19 genera diferentes reacciones en la población, que cada vez tienen más herramientas para expresarse y conocer las opiniones de los demás. Las redes sociales tienen un papel primordial en la comunicación de la población, por lo que este contenido podría servir como herramienta de vigilancia en salud pública y medio de comunicación útil y accesible en el manejo de crisis sanitarias.

The new coronavirus pandemic has represented a great public health challenge worldwide. In response, mitigation measures were adapted with the aims of preparing the healthcare system, reducing the impact of the disease and mitigating secondary alterations in the economic, social and political systems.1 These measures range from the early identification and isolation of suspected or diagnosed cases and the strengthening of hospital infrastructure2 to stricter measures such as suspension of massive public events and restrictions on the movement of people.3 Added to this, the continuous fear of contagion and the loss of loved ones have generated significant changes in individuals’ routines, new realities, an increase in external stressors, a decrease in social contact and an increase in uncertainty in the population.4

In previous pandemic experiences, a negative impact on mental health has been described due to depression, generalised anxiety, insomnia, post-traumatic stress, abuse of alcohol or other psychoactive substances, and psychosomatic disorders.5 The COVID-19 pandemic has been no exception.6,7 Up to a quarter of the population has reported mental health disorders such as insomnia, depression and anxiety.8 Furthermore, generalised control measures can differentially impact populations, so it is important to adapt these measures to the needs and resources of each community.9 This impact has been studied in different countries, especially in the northern hemisphere, using different instruments to measure factors such as stress, depression and anxiety.6,10 For example, it has been pointed out how isolation can be a factor that worsens pre-existing conditions, reflected in the development or worsening of habits, greater consumption of psychoactive substances, poor diet and poor sleep hygiene.11 However, we have not found any studies which have explored how the population expressed themselves and discussed their experiences on a day-to-day basis.

This can be facilitated by the growing use of social networks and other technologies in today’s world, since the digital sphere has been positioned as a space that allows users to express their affective dimension, as well as its modelling and amplification.12 As background to this, different social media platforms have been analysed to interpret user reactions to different events.13

Therefore, in search of strategies that allow a better understanding of the social phenomenon, the psychological and emotional manifestation of the population around the pandemic and the restrictive measures secondary to it, we seek to evaluate the perceptions and repercussions on the emotional well-being of the Colombian population due to the COVID-19 pandemic through a mixed analysis of the social network Twitter.

MethodsAn analysis of metrics and trends was carried out on Twitter, which currently has more than 340 million users. Its platform is global and seeks to be proactive in participating in debates which are generated at all levels of participation. It offers transparency in the results and exposure of its associated metrics.14

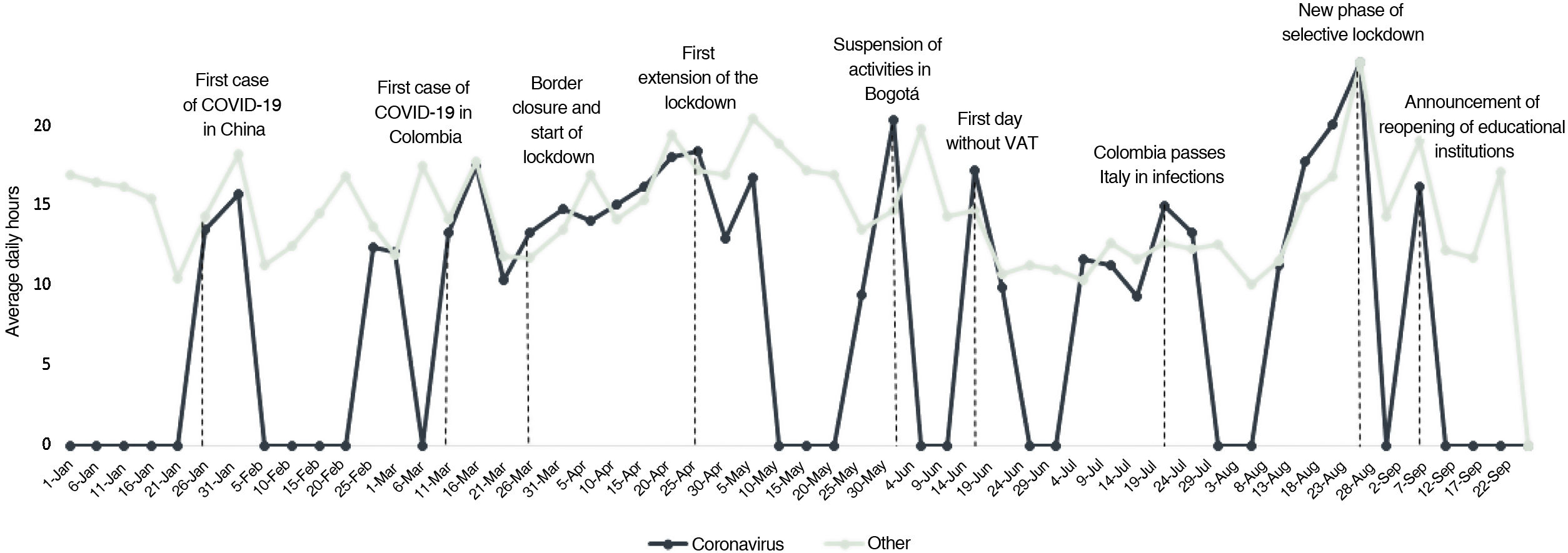

Initially, an analysis of Twitter trends (trending topics) was carried out on the Trendinalia15website, which is a tool for analysing global trends and acclaim on social networks and web pages, per day. On this page, the average duration in hours of the 20 most popular trending topics of the day in Colombia was calculated every five days from 1 January to 31 July 2020. For this average, four of the authors (FBR, MMQ, LM, SBM) divided the trends into two groups: related to COVID-19 and not related to COVID-19. Then, dates of events associated with the pandemic relevant to the country were identified, and they were related to the behaviour of trends associated with coronavirus.

An exploratory analysis was then made of the trends in Colombia represented by hashtag (#) or themes used from 1 January to 16 March through the same website. Once identified, we searched for the tweets with the greatest reach that included these mentions using the Mediatoolkit platform,16 a media monitoring instrument which tracks relevant mentions of a brand on the Internet and social networks in real time and makes it possible to identify the tweets which have used those mentions. We carried out two searches in two different periods: the first from 21 January to 23 March and the second from 14 to 21 June. We selected the 40 tweets with the greatest reach that the platform gave us. These selected tweets were categorised inductively for qualitative analysis and were summarised into the definitive categories for presentation in this study.

ResultsTopics not related to COVID-19 had greater reach than those related to coronavirus. However, increases and predominance of these topics were seen on some dates consistent with important events for this topic. It is worth noting that COVID-19 trends were more present at the beginning and middle of the evaluated period than at the end of the same period (Fig. 1).

Regarding the expressions of users on Twitter, in the first period evaluated there were multiple opinions related to COVID-19. Manifestations of approval and disapproval, solidarity and accusation were found, and there were prominent messages from well-known figures in the community (for example, political and social leaders and entertainment industry members) and from fewer citizens with less mass appeal. These trends were maintained in the second period evaluated, with slight changes in the particular topics. Categories were identified to group the messages inductively, and they are presented in order from greatest to least content (tweets related to politics and institutions, self-care and optimism, informative, citizen complaint, humour, fear, and stigma and discrimination).

Politics and institutionsOne of the advantages of social networks is bringing the population closer together and bridging the gaps in communication which tend to exist between different agents in society. In this category there were tweets directed at political leaders, where a great variety of opinions was found; most of the comments were critical of the delay in taking strict isolation measures, such as the implementation of lockdown or closure of the El Dorado International Airport. However, others support him: “President @IvanDuque, with all the respect you deserve, in the face of a pandemic of this magnitude, it is better to overreact than to move too slowly. The time to carry out curfew drills, to close airspace, to provide field hospitals, is NOW”; “The International Labour Organization estimates that 25 million jobs in the world are at risk. The Government in Colombia has not decreed anything to protect them and on the contrary, is sponsoring the labour massacre. #CoronavirusColombia…”.

In the second evaluation there were similar expressions; on this occasion, the measures taken in relation to the Day without VAT once again provided much to talk about, “Do you know who really wins with this irrational Covid Friday frenzy? Exactly! The banks with their exploited credit card interest rates. And Duque knows fine! #CovidFriday #coronavirus #DiaSinIVAEs”.

However, some users have been satisfied with the representation and decision-making of the national government. Other people contrasted and highlighted the work of local governors, “We are going to support our leaders. Let’s leave political differences aside and unite. My full support to the national, regional and district government. God give them wisdom… Nobody was prepared for this”, “Mayors and governors at the height of the emergency in many territories, some have managed to shield their regions and cities with measures that seem drastic but necessary. Duque says no, that until there are infections they cannot close anything”.

Self-care and optimismIn contrast, social networks constantly served as spaces of support among users, both to share caring information and to send optimistic messages. It also provides a space to discuss desires, feelings of love and tranquillity, and give occupational advice during this time. They also highlighted positive comments for all Colombians, which supported the idea of personal and group care, as well as highlighting the work of some members of the community and companies in particular: “If we look at it historically, and we are positive financially and socially, we can see this moment as an opportunity for a series of awareness and new habits to emerge at the same time. I am positive. Everything will be fine. (If the Governments are responsible) #coronavirus #COVID2019”, “Thank you to all the doctors and healthcare personnel who are on the frontline fighting this war #AplaudoANuestrosHeroes #CuarentenaPorLaVida [#I applaud our heroes #Lockdown for life] #Covid_19 #CoronavirusColombia…”.

People were able to express their experiences, referring to the care they would take and compliance with isolation instructions even when they did not have symptoms, and recognising the importance of each role and each participation to achieve a goal as a community and look after ourselves as a community, with solidarity: “We have to learn to play together!! #CuarentenaTotal #YoLeHagoCasoAClaudia #YoMeQuedoEnCasa #YoMeCuidoYoTeCuido” [Total Lockdown #I’m listening to Claudia #I’m staying at home #I’ll take care of myself I’ll take care of you]; “Everyone as far as we can, let’s help the people who live from day to day, many of us can stay at home, distressed obviously, but calmer than those who are on the street, let’s do something now!!! #YoMeQuedoEnCasa #EstaEnTusManos” [It’s in your hands], “Hey… don’t worry! Handshakes, hugs and kisses will soon return, until then, let’s stay home! That’s how we’ll reduce the risk of spreading COVID-19. By following the measures and recommendations, we will get out of this!”.

Despite the difficulties that have arisen due to the pandemic, several users have expressed various situations of encouragement and hope regarding what is currently happening and what will happen when the pandemic is definitively over: “#19Jun WHO optimistic that millions of doses of a COVID-19 vaccine will be available by the end of 2020. There are three candidate vaccines that are about to begin the final phase of human testing in the United States, the United Kingdom and China”; “Let’s make a viral video that shows a human chain made by farmers to get out a SICK soldier in times #COVID19”.

InformativePeople used this medium to share relevant news about what happened in Colombia and the rest of the world, such as statistics, news and data on control measures: “⚠#ATTENTION⚠ Hands are the main vehicle of coronavirus transmission and that is why washing them often is the most important measure to avoid infection. Prevent coronavirus ¡#EmpiezaPorTusManos!” [Start with your hands!].

Although most of the tweets talked about COVID-19 and its control measures, there were also informative protests about the social impact of the pandemic and its control measures: “Hairdressers and manicurists from small or independent businesses are already feeling the impact of the crisis and now they will have to close. They need support, many are mothers who are the head of the family. Health crisis affects hairdressers and shops…”.

The trend of tweets turned to reporting on the growth of diagnosed cases, with greater emphasis on Latin America, as it is the new focus of the pandemic. It also served as a means to report situations of vulnerability in specific populations: “RT @HINCAPIEDATOS: 83,325 cases of coronavirus China 63,276 cases of coronavirus Colombia Cross this bridge and we reach the Chinese”, “RT @AP_Noticias: Colombia: they warn that thousands of indigenous people are at risk of contracting COVID-19”

Citizen complaintsBut the criticism and comments were not limited to the leaders; there were also complaints about the bad behaviour of other citizens by the users of this social network. These messages were accompanied by the annoyance generated by finding that other people were not complying with social distancing measures, and comparisons were made with the countries that had the epidemic before ours: “No one is taking the #Covid_19 seriously. In northern Italy the late lockdown meant the number of cases soared, in Korea the #patient31 infected 1000 people. Parrandolombia, unlike those countries, does not have a quality health system. What a helpless situation!”, “I WANT TO CRY AND SCREAM Urgent measures NOW! Lots of people are being irresponsible about handling this situation! They’re exposing healthcare workers too! If there is no lockdown it’s going to be really bad for all of us and we won’t even be able to help each other! WHAT CAN WE DO! What a helpless situation!”.

In the second period evaluated, the complaints were directed towards the so-called “economic reopening”. They highlighted tweets that alluded to the fact that citizen culture regarding biosafety measures does not allow for successful commerce, because commerce would become a source of transmission of SARS-CoV-2: “RT @fdbedout: Every shop, every shopping centre this Friday, 19 June is an Olympic swimming pool of Coronavirus. The ‘day without VAT’ in the midst of a rapidly growing pandemic in Colombia is irresponsible”.

HumourDespite the news and negative feelings, although in the minority, there were satires regarding the situation; for example, this tweet that they related to the political history of the country: “If the coronavirus had appeared with following presidents they would say: Uribe: Lead for the coronavirus. Santos: There’s no such virus. Samper: That virus came up behind my back. Pastrana: El virus me dejó la silla vacía” [The virus left me an empty chair] (Joke in Spanish alluding to “La Silla Vacía” [Empty Chair], which is an independent digital news medium in Colombia).

The same type of humour persisted throughout the pandemic, where the measures taken and people’s performance were criticised: “RT @Matador000: If you get coronavirus today while standing in a long queue to buy things. You will get a 19% discount on the purchase of your coffin. *The discount does not apply to respirators or ICU beds”.

FearRelated to this news, fear was a feeling that could be perceived in the users’ tweets. The fear was related to uncertainty, to international news and to the realisation that the control measures were not being complied with by the whole population, which would have negative consequences: “It doesn’t seem like it, I’m really anxious, it’s going to be a very hard few days, besides, I don’t know why my brain decided to remind me of videos about the situation in Italy and how bad things are there. I’m scared :(”.

As the pandemic progressed, the perception of risk grew, highlighting that this can be serious, and not just for older people and people with comorbidities. There were also fears regarding the economy and the effects directly on health: “Today a student I taught this semester died from Covid-19, 22 years old, with no serious illnesses, he had been diagnosed days before and was at home with mild symptoms, today he woke up unable to breathe, they took him to the clinic and hours later he was dead”; “The resurgence of the pandemic in China and the expansion of the coronavirus in several US states have meant investors’ worst fears have returned in recent days”.

Stigma and discriminationDespite many calls for solidarity and working together, there was contrast, when we found some signs of discrimination and blaming towards the eastern community. These messages also contain calls for nationalism and for pointing at other nations as the cause of this pandemic: “The Republic of China gave us an aerosol pandemic. When the coronavirus is over, I promise to never buy Chinese products, I will dedicate myself to buying Colombian products and nothing else. I consider China to be dead after watching this video…”; “Let’s do a recount. H2N2 (1957–1958). Origin: Beijing. H3N2 (1968–1969). Origin: Hong Kong. SARS (2003). Origin: Guangzhou. Coronavirus (2019). Wuhan. All of these viruses have originated in China and all together they have taken millions of lives. “Why let it go just like that?”.

In this category, most of the expressions of stigma and discrimination changed target, they were no longer international accusations, but within our community, such as the stigmatisation of healthcare professionals and general services: “This type of discrimination against doctors and healthcare professionals in Colombia in the midst of the pandemic is outrageous, absurd and unacceptable”.

DiscussionThe impact of COVID-19 on mental health has been described in the literature from a clinical perspective.6,7 However, there are few approaches that investigate people’s day-to-day or informal expressions. Therefore, seeking to obtain a greater understanding of the social phenomenon during the implementation of control measures to prevent the spread of the virus and its psychological and emotional effect on the population, we decided to perform an analysis of one of the world’s best-known microblogging social networks. An increase was found in the expressions concerning the pandemic and the relationship between the trend of these topics and the population expressions generated.

Nearly 50% of the world’s population are active users of social networks, which provide a simple and effective means to disseminate information and opinions.17 From our results, we were able to see an obvious increase in popularity and reach (according to trending topics) of topics related to COVID-19 from January 2020. This variability in trend was associated with events related to COVID-19. For example, in January it coincided with the identification of the new coronavirus (20 January) and then the report of the first infected patient in Latin America (20 February); trends such as #SiLlegaElVirus [#If the virus arrives].

Another milestone in our country occurred on 6 March, when the first case was reported in Colombia, although topics related to COVID-19 were not a trend that day because the person was diagnosed in the afternoon. However, after that date, elevated trends are found during the rest of March, April and May. During that period, different events stood out, such as the establishment of mandatory isolation and the closure of borders, which generated multiple reactions and confrontations among citizens, as reflected in the cited tweets (#DuqueResponda, #PresidenteSiTenemos [#Duque Respond, #President, If We Have One]). In addition, on 21 March the first death from coronavirus in our country was reported, which coincided with a sustained increase in our results, which can also be explained by events such as the clashes in the La Modelo prison in Bogotá after the protests against the pandemic control measures, an event that was also reflected by users on Twitter.

There were also reactions related to the economic reactivation and control of the pandemic, such as the pilot plan for the gradual reopening of certain economic sectors and the first day without VAT held on 19 June. Secondary to this, a lot of controversy was generated, but mainly with rejection and criticism of both the organisers and the behaviour of the citizens, highlighting the trend #CovidFriday. Two weeks after the event, cases of infection increased and occupancy of intensive care units in Bogotá was over 90%,18 which was associated with an increase in expressions on social networks, as well as the demand for greater social control and complaints against political leaders (#DuqueNoEsMiPresidente, #BogotáTieneMiedo [#Duque is not my President, #Bogotá is scared]). However, to mitigate the negative impact on the economy, on 1 September the National Government withdrew mandatory social isolation, but that could not prevent an unemployment rate of 20%, and was followed by the Government’s decision to declare an economic recession, which has also been associated with higher rates of emotional distress, depression and attempted suicide.19,20

The evidence we have presented above shows that social networks have provided opportunities and challenges in communication during health crises. They can provide information in real time and give the chance for people to respond to that information, generating a space for dialogue and discussion about it. In this study, informative tweets were found about the pandemic and its control measures, but discussions were also generated around the secondary social impact, criticism of the Government, complaints about citizen behaviour and situations of vulnerability of specific populations. This is why a more important role has been highlighted for social networks than for traditional news media (where users only participate as recipients); Picard states that this has led to a “humanization” and “democratization” of communication on social media, which improves on the typical legacy of the traditional media.21 Social networks are positioned as a communicative space with greater reach and influence on and reflection in the general public, as it allows them to be part of a conversation.22 However, it has also been associated with changes in the population’s mood, mainly among adolescents.23 In addition, through this medium, users were able to share their experiences and feelings generated by the current situation. In our study, a higher proportion of feelings of sadness and worry were reflected, followed by optimism, similar to what was found in the Spanish population during this pandemic.24 This highlights the importance of identifying expressions through social networks since previous studies have indicated that both negative and positive emotions expressed can be contagious on the social network,25 and even that the language and psychosocial expressions used can help assess mental health.26,27

This can generate a change in people’s care and communication behaviours. In fact, in our results, there is less reference to issues related to the pandemic on the last dates analysed, even when Colombia was at its epidemiological peak (September 2020).28 This can be explained by the phenomenon of “pandemic fatigue” proposed by the WHO to refer to the use of biosafety measures, due to the exhaustion generated by the increase in stress, physical and emotional tension in the population, when they find that the pandemic persists despite the control measures implemented,29 all of which also reduces adherence to these measures. To counteract this situation, constant announcements on protection and prevention of COVID-19 have been proposed, but an overload of information can generate psychological fatigue and increase rejection of both the information and control measures, and greater distortion in risk perception.30

The study has a series of limitations. The population analysed was only active users of Twitter, which may leave a part of the population without representation. However, this is one of the social networks with the most users, and it allows them to easily express their ideas without restrictions based on job characteristics, as is the case with traditional media. Also, soft variables were evaluated without using standardised instruments. However, we would highlight the novelty of investigating the perception and emotions of the population in an environment where they can express themselves spontaneously; we believe this means our results can be of use for decision-making in health, in view of the fact that in the current context, accompanied by lockdown in several parts of the country, social networks greatly influence the mental health of the population.31,32

ConclusionsThe COVID-19 pandemic and its repercussions have impacted the population in social, economic and emotional terms. This generates different reactions in the population, which has increasingly more means available to express itself and hear the opinions of others. It would therefore be a good idea to expend greater efforts in monitoring the content generated on social networks as an instrument of public health surveillance, and as a useful and accessible means of communication in the management of health crises. Social networks now play a primary role in the population’s communication, and communication of risk and public health measures must adapt to this new reality and use this transformation as an opportunity for improvement when it comes to decision-making.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.