Describe the beliefs of parents about the mental disorders of their children who attended a paediatric outpatient clinic at a university hospital.

MethodsThis was a descriptive study with parents of children with mental disorders seen from January to May of 2018 at a high complexity hospital in Medellin, Colombia. Ninety-eight (98) parents of children and adolescents attending their first outpatient consultation with Paediatric Psychiatry were studied. An instrument designed by the investigators was applied to obtain demographic variables and beliefs about the origin of their child’s mental disorder, treatment and adjuvants.

Results49.9% of the 98 parents believed that their child had a mental disorder. 43.9% believed the disorder was inherited and 41.8% believed its cause was organic. 95.9% of the parents believed the child needed treatment, including psychotherapy (90.4%) and medication (58.51%). Among the alternative treatments the parents believed the child needed, healing was the most commonly cited by 27.5% of the parents. Of the adjuvant methods, the most commonly cited were reinforcing positive behaviour (82.7%) and correcting with words and setting a good example (72.4%).

ConclusionsNearly half of the parents believed their child had a mental disorder, the treatment that was most commonly considered was psychotherapy above medication, and the best adjuvant methods cited by parents were reinforcing positive behaviour, correcting with words and setting a good example.

Describir las creencias de los padres acerca de los trastornos mentales de sus hijos que asistieron a consulta externa infantil en una clínica universitaria.

MétodosEstudio descriptivo transversal realizado en padres de niños con trastornos mentales de una clínica de cuarto nivel de Medellín, Colombia, durante el periodo comprendido entre enero y mayo del 2018. Se estudió a 98 padres de niños y adolescentes que consultaron por primera vez a Psiquiatría Infantil. Se aplicó un instrumento elaborado por los investigadores con variables demográficas y de creencias sobre: el origen del trastorno mental, del tratamiento y sus coadyuvantes.

ResultadosEl 49,9% de los 98 padres evaluados creyeron que su hijo tenía un trastorno mental; en cuanto al origen de este, el 43,9% creía que era heredado y 41,8% por causas orgánicas. El 95,9% de los padres creía que sus hijos necesitaban tratamiento, de ellos, el 90,4% estimó la psicoterapia y el 58,51%, la medicación. Entre los tratamientos alternativos el más frecuente fue la sanación, con un 27,5%. De los métodos coadyuvantes en el tratamiento, los más frecuentes fueron estimular comportamientos positivos con el 82,7%, y corregir con palabras y dar buen ejemplo con el 72,4%.

ConclusionesEn este estudio casi la mitad de los padres pensaba que sus hijos tenían una enfermedad mental. El tratamiento más considerado por los participantes fue la psicoterapia, por encima del uso de psicofármacos. En cuanto a los métodos coadyuvantes, los padres consideraron principalmente el estimular comportamientos positivos, corregir con palabras y dar buen ejemplo.

Beliefs are a set of ideological principles held by a person or social group which are assumed to be true.1 Form a sociological point of view, beliefs are part of the representations that seek to integrate individual and social concepts into people’s behaviour.2

In psychiatry, studies have been made of the beliefs of patients in relation to the aetiology, treatment and care of people with mental disorders, and how these influence the seeking or rejection of mental health care. In the field of children’s mental health, it has been reported that 85.4% of parents of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) think it is a real disease, and the rest that it is a myth, a fad or an invention of the pharmaceutical industry.3

For the aetiology of psychiatric disorders in childhood, a study on the beliefs of parents of children with autism reported that they thought the disorder had been caused by problems during childbirth, the use of vaccines or the treatment given to their children.4

In another study on the beliefs of the parents of children with depressive disorder, according to the respondents, problems related to parenting are a fundamental part of the aetiology and drug treatment could lead to “addiction” and being “doped”.5

In contrast, adults with depression believe that the aetiology of their disorder is related to the following aspects: biological vulnerabilities (84.8% of patients believe that it is due to a biochemical imbalance, 77.4% to heredity); stress in adult life (family stress, 98.8%, interpersonal problems, 89.9%); and a history of adversity in childhood (abuse or neglect, 85.4%).6

A study carried out in the general population in Switzerland to determine social representations about mental disorders and psychiatric treatments reported that 24% did not believe that mental illness really existed. The participants did not differentiate between mental disorders. Moreover, they attributed psychosocial and psychological stressors, rather than biological or supernatural ones, as more common causes. In terms of treatment, they preferred family and individual psychotherapy to pharmacological management. With regard to medications, 46.6% doubted their effectiveness and 43.4% feared side effects.7

The beliefs held by parents do not always coincide with the epidemiological image of mental health in the region. The 2015 Colombian National Survey of Mental Health found that 49.8% of parents considered that the mental health of their children was excellent, 30.8% very good and 17.8% good. However, the same survey shows that up to 44.7% of this population does have different symptoms of mental disorders.8 In children with mental disorders, the beliefs of their parents and society can have a negative influence on their acceptance of the diagnosis and adherence to treatment.

Other studies in Colombia show that parents think the symptoms of disorders, such as bipolar affective disorder, are not due to an illness, but due to “lack of will” or “laziness”, and consider the treatment and care of the patient as a family burden.9,10

The aim of this research was to describe the beliefs expressed by the parents of children diagnosed with various mental disorders who attended a children’s outpatient clinic at a university hospital in Medellín, Colombia.

MethodsDescriptive cross-sectional study. The source of information was the parents (mother and father) of the children who attended a first child psychiatry consultation at the Clínica Universitaria Bolivariana (CUB), Medellín, Antioquia, Colombia, from January to May 2018 (98 people). The profile of patients who attend the CUB are children and adolescents referred there for psychiatric assessment. Some come from Antioquia’s neighbouring departments, such as Chocó and Córdoba, but the rest are local and the vast majority are from the metropolitan area of Valle de Aburrá, which includes the cities of Medellín, Envigado, Itagüí, Bello and Copacabana. The majority of patients belong to the private social security system.

The inclusion criteria were: parents of children and adolescents who attended the Child Psychiatry clinic. Exclusion criteria were: not being the parents or responsible for their upbringing; being employees of institutions responsible for the comprehensive protection of children and adolescents; that the child did not have a psychiatric diagnosis according to ICD-10; and refusal to participate.

The specific objectives were: to describe the demographic characteristics (age, level of education, occupation, economic status, type of family, religious practice); to describe the beliefs about the origin of the disease (mental disorder, hereditary, biological, non-biological); and to determine the beliefs regarding treatment and adjunctive interventions (psychotherapy, medication, alternative therapies, parenting methods, activities, environmental changes).

A self-completion survey-type instrument was constructed with operationalised variables, with 25 questions about parents’ beliefs about childhood mental disorders. It was based on the authors’ experience and the literature on beliefs related to mental illness.3,4,7 The questions had the following answer options to choose from: what/which?; do not know; other; or leave blank. They did not have the option of “none of the above”.

We carried out a descriptive analysis. For age, which was the only quantitative variable, the mean ± standard deviation and range were extracted. For nominal variables, absolute and relative frequencies (percentages) are presented. For purely exploratory purposes, the beliefs are presented discriminated by gender, socioeconomic status and religious practice. Comparisons between groups were made using the chi-square test, with a significance value of p ≤ 0.05. Socioeconomic status was defined according to Colombian Law 142 of 1994, which establishes the classification of residential properties in a municipal area, which is calculated based on Colombia’s Residential Public Services Regime. This classification establishes three groups: low, middle, high.11

This study was considered to be of minimal risk, according to resolution 008430 of 1993, was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki on research with human subjects were taken into account. The objectives were explained to all the participants and they were then asked to sign the written informed consent form. The study instrument was applied confidentially and anonymously.

With the information obtained, a database was created in SPSS 20 and the data were analysed in this same program.

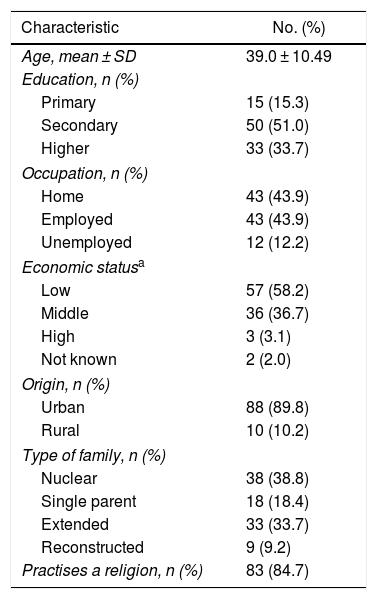

ResultsWe studied 98 parents of children with mental disorders, of which 93 were female and 5 male. Demographically, the age range of the parents ranged from 19 to 67 years, the majority with secondary schooling and low socioeconomic status. Other data are shown in Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of 98 parents of children diagnosed with mental disorders.

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 39.0 ± 10.49 |

| Education, n (%) | |

| Primary | 15 (15.3) |

| Secondary | 50 (51.0) |

| Higher | 33 (33.7) |

| Occupation, n (%) | |

| Home | 43 (43.9) |

| Employed | 43 (43.9) |

| Unemployed | 12 (12.2) |

| Economic statusa | |

| Low | 57 (58.2) |

| Middle | 36 (36.7) |

| High | 3 (3.1) |

| Not known | 2 (2.0) |

| Origin, n (%) | |

| Urban | 88 (89.8) |

| Rural | 10 (10.2) |

| Type of family, n (%) | |

| Nuclear | 38 (38.8) |

| Single parent | 18 (18.4) |

| Extended | 33 (33.7) |

| Reconstructed | 9 (9.2) |

| Practises a religion, n (%) | 83 (84.7) |

The most common mental disorders found in the children of the participants were: ADHD (40.8%); intellectual disability (16.3%); depressive disorder (8.2%); and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) (6.1%).

SD: standard deviation.

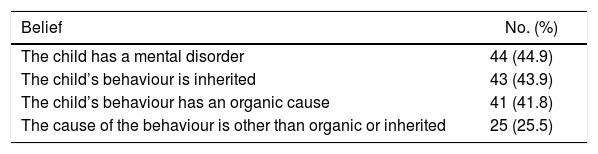

Out of all the parents, 44.9% considered that the child had a mental disorder; most believed that the child’s problems originated from biological causes (inherited or organic). Other data on these beliefs are shown in Table 2.

Beliefs about the origin of the disease of 98 parents of children diagnosed with mental disorders.

| Belief | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| The child has a mental disorder | 44 (44.9) |

| The child’s behaviour is inherited | 43 (43.9) |

| The child’s behaviour has an organic cause | 41 (41.8) |

| The cause of the behaviour is other than organic or inherited | 25 (25.5) |

Of the 25 people who thought that the origin of the disorder was other than organic or inherited, seven (28%) believed it was due to family conflict, five (20%) to reasons to do with the environment, two (8%) to witchcraft, one (4%) to a curse and one (4%) to food. We should clarify that the answers were not exclusive and that two (8%) respondents did not give any explanation.

When asked if what was happening to the child was due to an illness, 56 (57.1%) people answered yes. Of the remaining 42 (42.9%), 17 answered that it was due to lack of will (40.5%), four (10.8%) to lack of good manners, nine (21.4%) to poor parenting, and the answers were not mutually exclusive.

Beliefs about the need for and type of treatmentWe found that 94 (95.9%) of the people believed that the child needed some treatment. Of those, 85 (90.4%) believed that their child needed psychotherapy, 55 (58.51%) medication and 26 (27.6%) a neuropsychological assessment. These answers were not exclusive.

In 56 (57.1%) of the children, some medication had previously been prescribed to treat their disorder and 36 parents (64.3%) considered that they could develop adverse effects, with 18 (48.7%) thinking they cause addiction, 16 (43.2%) slowing down, 14 (37.8%) change in nature, 8 (21.6%) worsening of symptoms, seven (18.9%) physical changes, three (8.1%) sleep problems and one (2.7%) irritability.

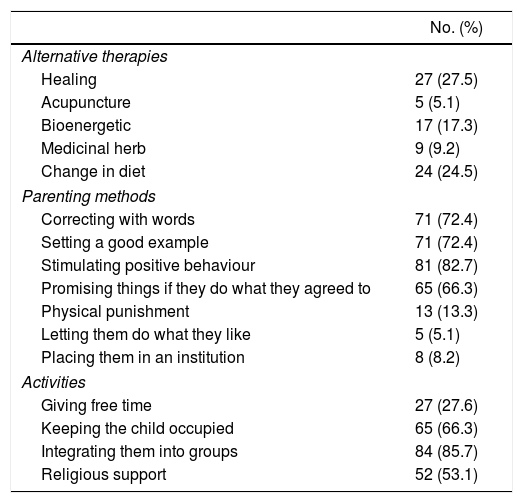

Beliefs about other types of interventions as adjuncts to treatmentWhen the parents were asked about what type of alternative therapies other than medication and psychological therapy they considered helped the treatment of their child, the one most considered was healing, at 27.5%.

In relation to parenting methods, the one considered of most help in improving symptoms was stimulating positive behaviour in the children (82.7%).

The activity that 84 (85.7%) of the parents thought was most important as an adjunct to the treatment was getting them involved in sports, religious or academic groups (Table 3).

Beliefs of 98 parents of children diagnosed with mental disorders about other types of interventions that could be adjuncts to treatment.

| No. (%) | |

|---|---|

| Alternative therapies | |

| Healing | 27 (27.5) |

| Acupuncture | 5 (5.1) |

| Bioenergetic | 17 (17.3) |

| Medicinal herb | 9 (9.2) |

| Change in diet | 24 (24.5) |

| Parenting methods | |

| Correcting with words | 71 (72.4) |

| Setting a good example | 71 (72.4) |

| Stimulating positive behaviour | 81 (82.7) |

| Promising things if they do what they agreed to | 65 (66.3) |

| Physical punishment | 13 (13.3) |

| Letting them do what they like | 5 (5.1) |

| Placing them in an institution | 8 (8.2) |

| Activities | |

| Giving free time | 27 (27.6) |

| Keeping the child occupied | 65 (66.3) |

| Integrating them into groups | 84 (85.7) |

| Religious support | 52 (53.1) |

Of the total number of parents, 53 (54.1%) considered that changes made in the places where the child lives might have a positive or negative effect on the disease. Of these, 47 (88.7%) believed that the child would improve with changes: in the home (36; 76.6%), at school (29; 61.7%) and in the neighbourhood (25; 53.2%).

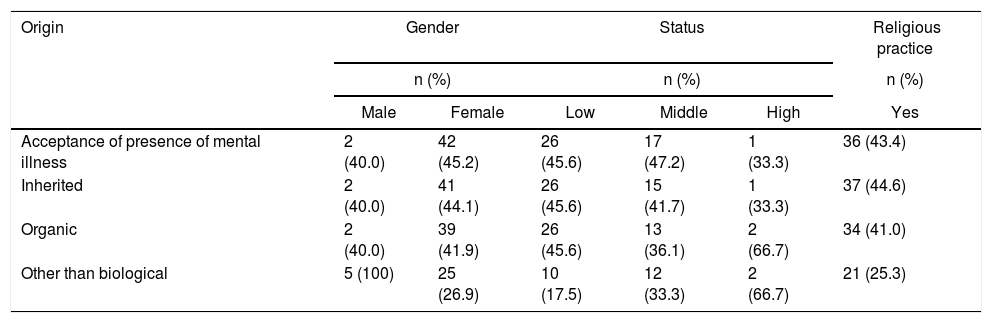

Parents’ beliefs about the origin of the disease according to relevant demographic dataThe beliefs about the origin of the disease according to gender, socioeconomic status and religious practice are shown in Table 4. There were no statistical differences according to the grouping variables (all p values >0.05). Of the total sample, 93 were female and 5 male; 100% of the male parents considered that the origin of the child’s disorder was other than biological. Those with the highest socioeconomic status were those who least believed that their children had a mental illness. Of the people who practised a religion, 21 (25.3%) thought that the origin of the disease was other than biological.

Beliefs about the origin of the disease according to gender, status and religious practice of the participating parents.

| Origin | Gender | Status | Religious practice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||

| Male | Female | Low | Middle | High | Yes | |

| Acceptance of presence of mental illness | 2 (40.0) | 42 (45.2) | 26 (45.6) | 17 (47.2) | 1 (33.3) | 36 (43.4) |

| Inherited | 2 (40.0) | 41 (44.1) | 26 (45.6) | 15 (41.7) | 1 (33.3) | 37 (44.6) |

| Organic | 2 (40.0) | 39 (41.9) | 26 (45.6) | 13 (36.1) | 2 (66.7) | 34 (41.0) |

| Other than biological | 5 (100) | 25 (26.9) | 10 (17.5) | 12 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 21 (25.3) |

There are no significant differences in any of the reported groups (p > 0.05).

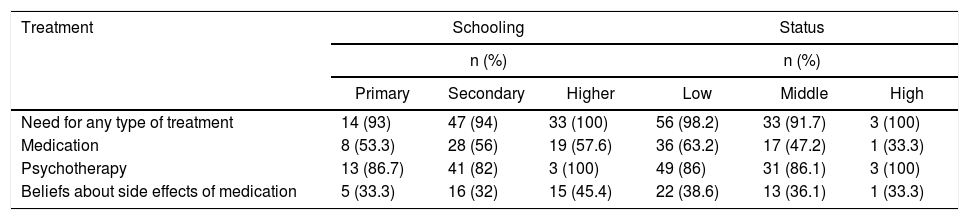

Analysing the beliefs about treatment according to schooling and status, we found that more than 90% of the people of all three strata believed that their children needed treatment, 36 (63.2%) of the low stratum considered pharmacological management was necessary, and three (100%) of the high stratum that psychotherapy was necessary. No statistical differences were found according to the grouping variables (all p values >0.05). Other data about treatment, schooling and status are shown in Table 5.

Beliefs about treatment according to schooling and status.

| Treatment | Schooling | Status | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Primary | Secondary | Higher | Low | Middle | High | |

| Need for any type of treatment | 14 (93) | 47 (94) | 33 (100) | 56 (98.2) | 33 (91.7) | 3 (100) |

| Medication | 8 (53.3) | 28 (56) | 19 (57.6) | 36 (63.2) | 17 (47.2) | 1 (33.3) |

| Psychotherapy | 13 (86.7) | 41 (82) | 3 (100) | 49 (86) | 31 (86.1) | 3 (100) |

| Beliefs about side effects of medication | 5 (33.3) | 16 (32) | 15 (45.4) | 22 (38.6) | 13 (36.1) | 1 (33.3) |

There are no significant differences in any of the reported groups (p > 0.05).

This research helped us learn about the beliefs of parents whose children consulted the child psychiatry unit at a university hospital in Medellín (Colombia) regarding their mental disorders. The demographic data describe a population with predominantly low economic status, similar to the country’s general population. The studied population had higher rates of middle and higher education, above the levels of the general population in Colombia.12,13 The figures for the diagnoses treated in our clinic were similar to those seen at other university hospitals, where ADHD is the most common disorder.14

Beliefs about the presence and origin of mental illnessLess than half of the parents believed that the child had a mental illness and that the origin was hereditary or due to some biological factor. A quarter considered that the origin was neither hereditary nor biological. Other authors who have studied beliefs about specific diseases describe similar findings.15 A study carried out in the general Spanish population found that 68.0% believed that the origin of schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder (BD) was a biological alteration of the brain, and 45.0% thought that the origin was hereditary.15

Another study in Peru on parents’ knowledge about ADHD found that 44.7% thought the origin was biological.16 In Mexico, a study on parents of children with ADHD found that 85.4% thought it was a disease.3 This figure is higher than that found in our study, where most of the children had ADHD, which is the most prevalent mental disorder in the child and adolescent population.17,18

A quarter (25.0%) of those studied believed that the origin of the disease was other than biological (family conflict and environmental factors). Other researchers in Latin America have found similar results in parents and teachers of children with mental disorders, who considered abuse, poor parenting, myths and fashion to be the origins.3,16,19

More than half of the parents thought their children did not have a mental illness. This may be explained by reasons such as stigma and discrimination surrounding such conditions, or because the respondents think the explanation lies in family conflicts or environmental situations affecting the child’s behaviour.20

The main cause of mental illness other than biological, according to the parents, was family conflict. It is known that family stress can trigger, but also be a consequence of, mental disorders.21 Clinicians therefore need to assess the degree of concordance between the belief and the reality in each specific case, as beliefs like this can help in terms of establishing treatment when they coincide with reality, but otherwise they can also hinder it.

In line with what parents believe, empirical research has shown that family conflict is a risk factor/trigger for mental disorders.21 Perhaps this overlap between beliefs and medical knowledge could be useful for formulating prevention programmes aimed at improving family harmony and helping families through multidisciplinary team interventions.

Beliefs about the treatmentThe majority of parents of all economic strata and all educational levels thought that their children needed treatment. This is positive, as it may indicate their willingness to accept that there are conditions that can be treated and modified. Their first preference was for psychotherapy and, in second place, medication. This could be explained by the stigma towards the use of drugs, the fear of their side effects, the fact that there is greater acceptance and less suspicion of psychotherapy, and that it was their first consultation with the Psychiatry Unit and they had not yet received psychoeducation. These results are similar to those obtained in other studies in the region.3,7,15,19,22 Understanding these aspects may be useful in terms of directing healthcare towards a multidisciplinary approach that includes psychoeducation and pharmacological and psychosocial therapies as an integral form of treatment. In addition, psychotherapy, family psychoeducation and family therapy have been proven to produce good results in the management of childhood mental disorders, such as ADHD,22–24 oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), depression and anxiety,25,26 and BD.27

The low-income parents were the ones who believed the most in the use of medications, probably because they think that drug treatment will produce a faster response, enabling the child to continue schooling and both the child and the parents to resume their usual activities. These results are similar to those reported by other authors.28 The fact that the lower strata may have less social support and less access to adjuvant therapies may mean they see medication as an alternative solution to help alleviate the day-to-day stress often suffered by low-income families because of their additional psychosocial risk factors.

Beliefs about the adverse effects of medicationsAs reported by other researchers, the most significant finding with regard to the possible adverse effects of medications was that parents believed the drugs used for treatment would cause addiction.5,7,29 They also believed that they made the child slow and changed their nature. This is probably because they are so used to their child’s impulsive behaviour, hyperactivity and psychomotor restlessness that, particularly in children with externalising disorders, as the medications act by controlling these symptoms, when they start being regulated by the drug, many parents are surprised by the change.

These parental beliefs about psychotropic drugs can generate fear of using them, because they think that they will cause addiction and change their children, and this leads to them not administering the treatment as instructed by the psychiatrist. It is known that any drug can cause side effects that result in having to modify or withdraw treatment.30 To reduce the impact of these beliefs, it is important for the treatment team to clarify that most psychoactive drugs are not addictive and that the side effects of some medications can be self-limiting over time. The clinician needs to explain that if the drug is not well tolerated, they will look for an alternative. In any event, the risks and benefits will be weighed up in order to improve adherence to treatment.

Beliefs about adjuvant treatmentsThe most common belief was in healing. It is known that spirituality reduces stress in people with anxiety disorders, epilepsy and depression, helps them cope with the disease5,31,32 and provides therapeutic support which reduces suffering.33 In Colombia, 82.5% of the people practice some religion, which may explain this belief.34

In terms of parenting methods, most parents considered that stimulating positive behaviour, setting a good example and correcting with words helped to improve their child’s behaviour. In parenting guidelines, it is known that reinforcing positive behaviour leads to increased positive behaviour and a decrease in negative and risky behaviour, as does modelling proactive behaviour.35 Similarly, studies in Colombia and Costa Rica showed that parents consider dialogue as a form of correction (80%) combined with physical punishment in up to 50%, unlike our findings, where this was only 13.3%.36,37

Among parents’ beliefs about the activities they considered as adjuncts to the treatment, integrating the child into groups (sports, artistic) was the most common. Physical exercise in children with mental disorders is believed to have a positive impact on their mental health.38

Beliefs about the presence and origin of the illness according to gender and statusWhen comparing demographic information in relation to beliefs about whether or not the child had a mental illness, we found that slightly less than half of the participants considered that the patient had a mental illness, with the rate slightly higher in female parents. This can be explained by the fact that women are the primary caregivers of children and the sick, so they may have more knowledge about them and their symptoms and behaviour.9,39

In terms of beliefs about the origin of the disorder, we found those belonging to the middle and lower strata more likely to believe that the child had a mental illness. In the higher strata, the most common belief was that the disease was biological. This was consistent with other studies.40 The lack of introspection about the origin of the disease in all strata could be explained by the stigma surrounding this type of diagnosis, a lack of knowledge and a form of initial denial, which is an emotional protective factor.41

LimitationsThis is a cross-sectional study and we cannot know how stable the beliefs are over time or how they may change as a result of psychoeducation. We believe that, once the parents’ beliefs have been established in the initial assessment and the therapeutic plan has been agreed, we need to keep reassessing what the parents think and how they feel about their child’s mental health and the prescribed treatment. The population cared for in our centre does not necessarily represent the general population. However, it is important to know what happens to the beliefs of parents whose children are treated at specialised university hospitals. In fact, according to the sociodemographic data described in our results, a wide range of people with diverse sociodemographic characteristics were included in this study.

The patients who had come to the hospital’s child psychiatry clinic for the first time were referred from other institutions and by different healthcare professionals, such as psychologists, neuropsychologists, general practitioners, paediatricians and neuropaediatricians. Some had already started pharmacological treatment and were receiving it at the time of the study, which may indicate that its use was accepted by the parents. Some had also had psychotherapy, while other patients had never received any type of prior pharmacological or psychotherapy treatment. These different experiences can positively or negatively influence beliefs regarding the use of medications and other treatments, but we did not analyse this area. However, it is an important aspect that could be a subject of future research.

ConclusionsThe demographic information in this study is similar to that reported in the general Colombian population. Slightly less than half of the parents considered that the origin of the disease was biological and most believed that their children needed treatment, with psychotherapy the preferred treatment. The treatments most often considered as adjuvants were stimulating the children’s positive behaviour and integrating them into groups. Recognising, respecting and taking into account the beliefs of the parents could improve the doctor-patient relationship, introspection about the disease and adherence to treatment.

FundingThis work was funded by the Dirección de Investigación e Innovación (CIDI) [Directorate for Research and Innovation] of the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana (project: 919B-10/17-45) in Medellín, Colombia. The CIDI did not participate in the design of the study or in the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data. It did not interfere in the writing of the article or in the decision to send it for publication.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Ricardo Ramírez C, Álvarez Gómez M, Franco Vásquez JG, Zaraza Morales D, Caro Palacio J. Creencias de los padres acerca de los trastornos mentales de sus hijos en una consulta universitaria en Colombia. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:108–115.