It has been said that mental illnesses are characterised by poor decision making; there is some neuroscientific evidence of specific alterations in performance in decision making tests, but little is known about how patients make choices about their own treatments.

MethodsFocus groups with patients from two psychiatric clinics, with discourse analysis.

ResultsFive deductive categories (tools, capacity, therapeutic relationship, method and family and network), plus one additional category from the analysis (stigma), and 35 inductive (posterior) categories were considered. The categories are analysed and the findings presented.

ConclusionsPatients express a need for greater participation in decisions about their treatment, and a more symmetrical psychiatrist-patient relationship, involving families. Decisions may be changed due to stigma, barriers to treatment access, and previous experiences.

Se ha dicho que las enfermedades mentales se caracterizan por la mala toma de decisiones; existe evidencia de neurociencias de alteraciones específicas en el desempeño en pruebas relacionadas con decisiones, pero poco se conoce sobre cómo los pacientes eligen acerca de su tratamiento.

MétodosGrupos focales con pacientes en 2 clínicas psiquiátricas, con análisis de discurso.

ResultadosSe consideraron categorías previas (ayudas, capacidad, relación terapéutica, método, familia y red), con una categoría adicional (estigma) producto del análisis y 35 categorías inductivas. Se analizan las categorías, se presentan los hallazgos.

ConclusionesLos pacientes expresan necesidad de mayor participación en elecciones sobre su tratamiento y una relación más simétrica con el psiquiatra, con participación de las familias. Las decisiones pueden alterarse por el estigma, las barreras de acceso al tratamiento y las experiencias previas.

The participation of patients in decision-making (DM) about their treatment is related to clinical, legal, ethical and social aspects.1–3 Greater participation emphasises the autonomy of the subjects and the rights of users,4,5 which results in a change from passive use to active participation in the treatment process.6–8 There are policies that require the participation of patients in decisions about their treatment, although the practical repercussions are not clear.4,9 In Colombia, mental health law considers the patient as the recipient of the information and their participation in the decision is established through informed consent to treatment.10

The implementation of models that promote the participation of patients with mental illness in their treatment poses significant challenges and questions.4 According to the WHO (2012), the active participation of patients with mental illness in their treatment is one of the greatest challenges in mental health.11,12 Recovery-oriented mental health practice emphasises the autonomy and empowerment of patients and efforts to protect their rights.7,8,13,14 The priorities of patients with mental illness concerning their treatment cover a wide range of issues, such as access, opportunity, safety, continuity and costs,4,15,16 and show high levels of unmet needs.17,18

DM is the choice of an alternative to solve a current or potential problem, even without clear conflict.19 In medicine, it is taught with models from the social sciences and economics,20 such as decision trees and the evaluation of benefits and probabilities.20,21 These approaches to DM are generally not presented to the patient.

Mental illnesses alter DM: there are studies on different disorders that show variations in the tests that measure DM ability and DM tasks according to diagnoses,22–25 although the presence of mental illness, for example schizophrenia, does not necessarily alter the ability to make a decision.26 A big question is how to address difficulties in DM for patients with mental illness. For this, emphasis has been placed on the development of communication and negotiation skills, health literacy,27 health numeracy28 and the ability to recognise signs and symptoms.4

The goal is evidence-based decision making, but this can be a difficult construct with varied meanings and relevance for mental health workers,29 and difficult to translate to patients. To make decisions, patients use both personal history and factual information.30 According to the uncertainty management theory (UMT), patients face uncertainty in DM in various ways.31 Although not all patients seek to reduce it, there are many strategies to do so, such as actively searching for information.12

Poor DM in people with mental illness has an impact on individual and social functioning, regardless of the symptoms of each disorder.32 Decisions are altered as a result of deficits in basic neuropsychological processes, such as attention, memory and inhibitory response, which are clinically expressed in outcomes such as low rates of adherence to drug treatment, substance use disorders and metabolic syndrome.32 Alterations in performance on tests to evaluate DM in patients with mental illness reflect alterations in the “cognitive control network”, which includes the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, the medial prefrontal cortex, the anterior cingulate cortex, parietal cortex, motor areas and cerebellum.32

Decision-making ability includes the ability to understand relevant information, think rationally about the risks and benefits of potential options, appreciate the effects on the person, assess the consequences of decisions, and express the choice.33,34 An autonomous decision includes: (a) acting voluntarily, free from external coercion; (b) having sufficient information about the decision to be made (objective, risks, benefits and possible alternatives), and (c) having the ability (cognitive, volitional and affective) that allows for understanding, assessing and properly managing the information, making a decision and expressing it.34–36

In clinical practice, there are different models of DM1,19: (a) paternalistic: the doctor decides about the treatment and the patient does not participate actively; (b) informed decision: the doctor provides relevant information, the patient decides – it implies greater autonomy in the patient's choice; (c) interpretive: the professional guides and advises according to their values, and (d) joint decision making (JDM): the patient and the doctor participate in DM in a process of information, deliberation and shared decision making.

Although the JDM model is valued because it involves greater patient participation and autonomy, actions must be taken to improve DM and communication skills in order to participate in the process,8,37,38 using aids or tools that help patients to choose and providing information about the options and associated risks and benefits.39 This results in greater patients satisfaction and involvement in decisions, with a greater understanding of treatment options, a more realistic perception of risks, better quality of decisions and greater participation in screening, without increasing anxiety.4,9 There is a need to evaluate its cost-effectiveness, its impact on adherence and its use in populations with a low level of education.39

Some studies have shown that psychiatrists do not adequately involve patients in decisions about their treatment. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate which patient variables allow JDM and how they would affect outcomes.9 Adequate communication is imperative in health care.12 It is possible to accelerate the involvement of patients through strategies such as supportive communication, which explicitly recognises the patient's emotional state or motivations,12 and alliance-forming communication, which involves asking the patient about their preferences to encourage their involvement, agreeing with or supporting their requests.40

Clinical DM requires the integration of information on the patient's clinical condition and their circumstances, the relevant evidence on their clinical condition, and the patient's preferences and actions regarding the options.41 Most DM models focus on the role of the doctor and the patient, emphasising autonomy; the role of family and friends has not been adequately explored. There may be cultural differences: for some eastern cultures, autonomy does not seem to be so important and the role of the support network is more established.8 Not taking the environment into account can result in contextual errors and an inappropriate care plan,41 since cultural beliefs and attitude towards the disease are expressed in preferences and choices.41 Incorporating context into care planning is described as ‘in-context care’ or patient-centred DM.41

Currently, there is no research in Colombia on experiences, opinions and preferences in decision-making in psychiatry that addresses the patients’ point of view.

MethodsThe project was approved by the ethics committee of Pontificia Universidad Javeriana and Hospital Universitario San Ignacio.

Research question: what are the experiences, preferences and opinions of patients regarding their mental illness and their implications on decision-making? Type of study: focus groups. Study population: patients seen in the day hospital programme of two psychiatric institutions in Bogotá who gave consent to participate in the study. Inclusion criteria: patients from participating institutions, contacted for an appointment, who were not in an acute phase, could participate in the activity and signed an informed consent form. Exclusion criteria: clinical condition that prevented participation in the group.

Five focus groups were conducted: three in institution A and two in institution B.

Sample size: 49 patients (institution A: 20 patients; institution B: 29 patients) of both sexes, of legal age and with different diagnoses.

Procedure: meetings were announced in outpatient programmes at both institutions, and were held in day hospital facilities. They were attended by inpatients, day hospital patients and outpatients. With their prior verbal consent and after signing the attendance list, patients participated in group sessions lasting two hours each, beginning with the presentation of the topic and encouraging participants’ opinions on opinions, experiences and preferences regarding DM in their own treatment. It was established that opinions would be discussed while maintaining anonymity and that all opinions would be respected. Clarifications were made regarding DM models, information searches, help in DM, and the focus of the sessions was maintained. The moderator tried to ensure that all attendees participated, while respecting if some attendees did not express their opinion.

Audio recordings of the sessions were made for verbatim transcription in Word and subsequent analysis of the contents by the author. The focus was decision-making in clinical care. Descriptions that could identify the user were omitted.

The previous analysis categories (deduced) were based on a systematic literature review: decision-making ability, method, aids, therapeutic relationship and support network. The phrases recorded were grouped into the previous categories; grouping was performed looking for similar themes by emerging (induced) categories of the included accounts and were coded, looking for exclusionary categories.

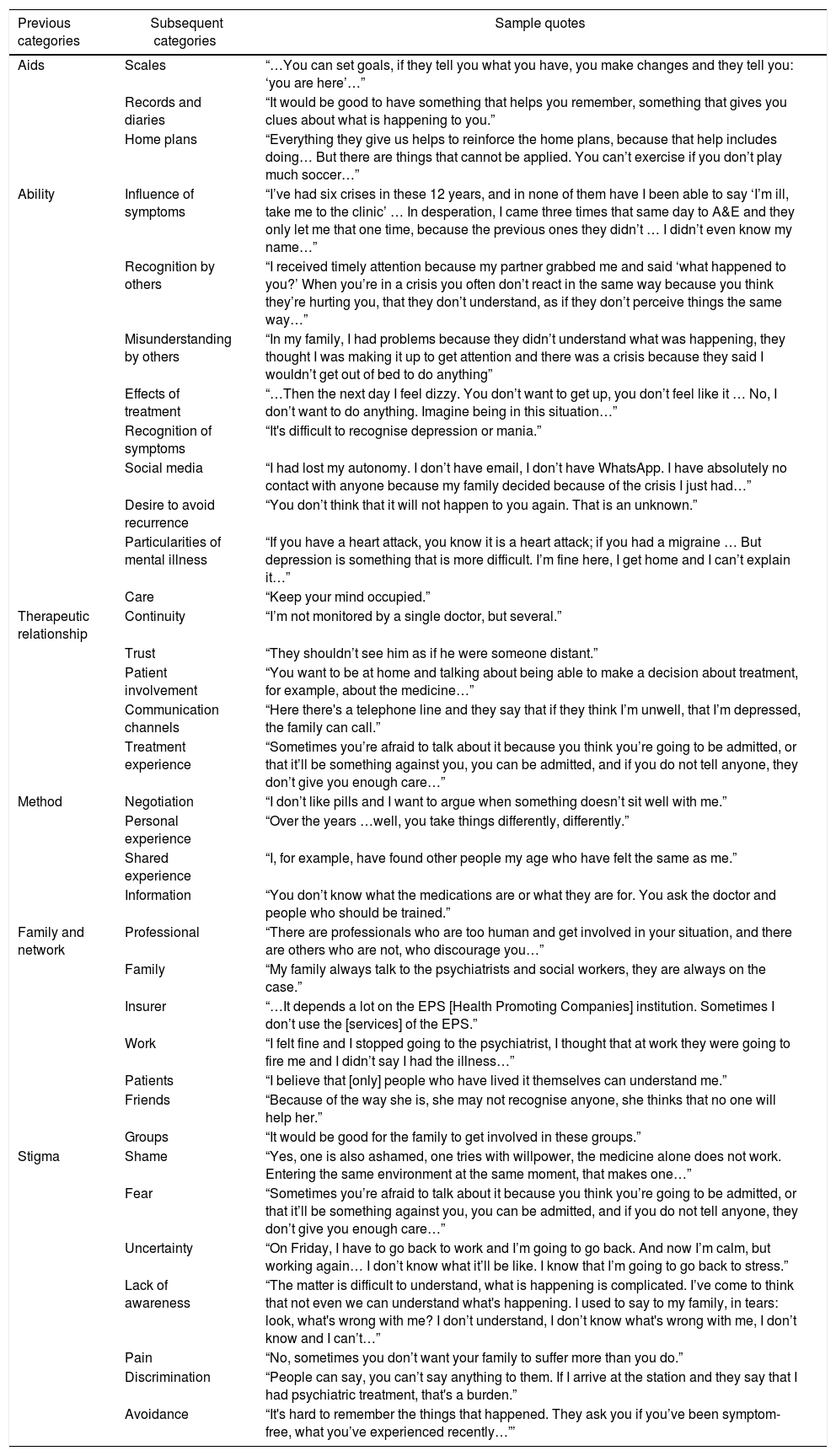

ResultsFive previous categories were established: decision-making aids, decision-making ability, therapeutic relationship, method and family, and support network. In accordance with elements that emerged in the recordings, an additional one (stigma) was analysed. Fragments of the session transcripts were placed in the categories; subcategories were established according to specific topic, resulting in 35 subsequent categories (Table 1).

Analysis categories.

| Previous categories | Subsequent categories | Sample quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Aids | Scales | “…You can set goals, if they tell you what you have, you make changes and they tell you: ‘you are here’…” |

| Records and diaries | “It would be good to have something that helps you remember, something that gives you clues about what is happening to you.” | |

| Home plans | “Everything they give us helps to reinforce the home plans, because that help includes doing… But there are things that cannot be applied. You can’t exercise if you don’t play much soccer…” | |

| Ability | Influence of symptoms | “I’ve had six crises in these 12 years, and in none of them have I been able to say ‘I’m ill, take me to the clinic’ … In desperation, I came three times that same day to A&E and they only let me that one time, because the previous ones they didn’t … I didn’t even know my name…” |

| Recognition by others | “I received timely attention because my partner grabbed me and said ‘what happened to you?’ When you’re in a crisis you often don’t react in the same way because you think they’re hurting you, that they don’t understand, as if they don’t perceive things the same way…” | |

| Misunderstanding by others | “In my family, I had problems because they didn’t understand what was happening, they thought I was making it up to get attention and there was a crisis because they said I wouldn’t get out of bed to do anything” | |

| Effects of treatment | “…Then the next day I feel dizzy. You don’t want to get up, you don’t feel like it … No, I don’t want to do anything. Imagine being in this situation…” | |

| Recognition of symptoms | “It's difficult to recognise depression or mania.” | |

| Social media | “I had lost my autonomy. I don’t have email, I don’t have WhatsApp. I have absolutely no contact with anyone because my family decided because of the crisis I just had…” | |

| Desire to avoid recurrence | “You don’t think that it will not happen to you again. That is an unknown.” | |

| Particularities of mental illness | “If you have a heart attack, you know it is a heart attack; if you had a migraine … But depression is something that is more difficult. I’m fine here, I get home and I can’t explain it…” | |

| Care | “Keep your mind occupied.” | |

| Therapeutic relationship | Continuity | “I’m not monitored by a single doctor, but several.” |

| Trust | “They shouldn’t see him as if he were someone distant.” | |

| Patient involvement | “You want to be at home and talking about being able to make a decision about treatment, for example, about the medicine…” | |

| Communication channels | “Here there's a telephone line and they say that if they think I’m unwell, that I’m depressed, the family can call.” | |

| Treatment experience | “Sometimes you’re afraid to talk about it because you think you’re going to be admitted, or that it’ll be something against you, you can be admitted, and if you do not tell anyone, they don’t give you enough care…” | |

| Method | Negotiation | “I don’t like pills and I want to argue when something doesn’t sit well with me.” |

| Personal experience | “Over the years …well, you take things differently, differently.” | |

| Shared experience | “I, for example, have found other people my age who have felt the same as me.” | |

| Information | “You don’t know what the medications are or what they are for. You ask the doctor and people who should be trained.” | |

| Family and network | Professional | “There are professionals who are too human and get involved in your situation, and there are others who are not, who discourage you…” |

| Family | “My family always talk to the psychiatrists and social workers, they are always on the case.” | |

| Insurer | “…It depends a lot on the EPS [Health Promoting Companies] institution. Sometimes I don’t use the [services] of the EPS.” | |

| Work | “I felt fine and I stopped going to the psychiatrist, I thought that at work they were going to fire me and I didn’t say I had the illness…” | |

| Patients | “I believe that [only] people who have lived it themselves can understand me.” | |

| Friends | “Because of the way she is, she may not recognise anyone, she thinks that no one will help her.” | |

| Groups | “It would be good for the family to get involved in these groups.” | |

| Stigma | Shame | “Yes, one is also ashamed, one tries with willpower, the medicine alone does not work. Entering the same environment at the same moment, that makes one…” |

| Fear | “Sometimes you’re afraid to talk about it because you think you’re going to be admitted, or that it’ll be something against you, you can be admitted, and if you do not tell anyone, they don’t give you enough care…” | |

| Uncertainty | “On Friday, I have to go back to work and I’m going to go back. And now I’m calm, but working again… I don’t know what it’ll be like. I know that I’m going to go back to stress.” | |

| Lack of awareness | “The matter is difficult to understand, what is happening is complicated. I’ve come to think that not even we can understand what's happening. I used to say to my family, in tears: look, what's wrong with me? I don’t understand, I don’t know what's wrong with me, I don’t know and I can’t…” | |

| Pain | “No, sometimes you don’t want your family to suffer more than you do.” | |

| Discrimination | “People can say, you can’t say anything to them. If I arrive at the station and they say that I had psychiatric treatment, that's a burden.” | |

| Avoidance | “It's hard to remember the things that happened. They ask you if you’ve been symptom-free, what you’ve experienced recently…”’ |

Each category was analysed in order to deepen the analysis and seek a tentative formulation of a model or theory, as follows:

- 1.

Selection of data contained in the category: includes the verbatim transcripts of fragments.

- 2.

Description: a general description of the findings according to the fragments from each category.

- 3.

Relationship between variables: aims to expand the selected data in each category with other categories of analysis.

- 4.

Data review: looks for elements that are present or absent in each category.

- 5.

Possible explanations: an attempt to find explanations common to the fragments contained in each category.

- 6.

General conceptualisation: looks for an in-context explanation, expanding to historical, cultural explanations, etc., beyond the group in attendance.

- 7.

Tentative formulation of new hypotheses: if possible, attempts to formulate hypotheses with the above elements.

- 8.

Search for new findings in the data: attempts to go back to the data to find other possible explanations.

The data from the transcription are presented, according to analysis of the discourse, whether in the general conceptualisation, the tentative formulation of new hypotheses or the search for new findings in the data, according to the level of analysis reached. The full analysis table is available from the author.

For this article, the six categories of analysis are presented with the general analyses contained in the subcategories.

DiscussionDecision making abilityPatients recognise that symptoms can interfere with DM, leading to them not following care recommendations and the treatment plan and rejecting the alternatives provided. This information is only understood a posteriori. Recognition does not always occur in a timely or quick manner, and it is more difficult in the first episodes of illness and early symptoms, which leads to a delay in the decision to consult a professional and communicate changes. The difficulty of putting into words what the patient has experienced makes joint DM difficult, since the options and considerations are not always made explicit.

Often, it is not the patients who recognise the symptoms, it is people close to them, particularly family or co-workers, who notice and make decisions about the treatment, even against the patient's will. However, the people around them are not always able to properly recognise and interpret symptoms, and decisions are sometimes made based more on prejudice or rejection than on support and health care.

Many patients are not prepared to recognise partial response and adverse events from treatment. Often times, decisions to stop taking medication or to take it irregularly have to do with the appearance of adverse events or the failure to produce the individually expected response, which is not always communicated to the doctor.

The use of social networks and contact with health care personnel show different types of relationships that can favour or hinder DM on personal care, given the amount of information, which is not always congruent and evidence-based or beneficial for treatment. In addition, it is necessary to select and analyse the information to make decisions.

Some patients struggle to accept mental illness. This process can take time and explains some of the decisions they make during the course of the illness. The desire to avoid new episodes leads some patients to associate treatment with the likelihood of recurrence, which leads to non-compliance and abandonment of treatment.

For some patients, it is difficult to understand mental illness with the non-psychiatric disease model, which leads them to search for different treatments such as alternative medicine, or religion-based or philosophical treatments.

Therapeutic relationshipPatients value a more symmetrical, collaborative and helpful doctor-patient relationship, emphasising providers that treat them like humans. Trust in the relationship allows for negotiating alternatives and changes to the treatment regimen.

Patients express a desire to participate more actively in their care, with greater verbal expression of their treatment experience, and the information shared with the doctor is not always explicit. This makes it difficult to properly assess the therapeutic response and the options to consider.

Consultation is the ideal time for communicating information and DM. Other channels such as telephone support are less common. In the sample, there was no reference to the use of websites, e-mails and the like.

Patients seek continuity in psychiatric treatment, but also change doctors when the expected improvement is not obtained.

Early treatment experiences can lead to rejection and scepticism, which impact the current relationship. It is important to address prior experiences when providing information and making treatment decisions.

MethodPatients want to be able to consider treatment options, discuss the effects of medication, which is not always possible when the paternalistic model of care and hierarchy is emphasised.

Previous personal experience of having suffered a crisis is valued for individual decision-making, and acceptance of drug treatment is more frequent after other attempts without adequate adherence to treatment.

Getting to know the experiences of other people who have faced similar situations helps patients in the self care process, since it is clearer when the other person is perceived as a peer due to their age, diagnosis and other characteristics. Patients frequently have access to the experience of other people, as users of the same institution or through user associations.

There are documented difficulties and barriers in accessing quality information. Patients emphasise that they are recipients of information, although the transmission of information is empowering, based on the educational model. Patients access information through various means, formally and informally, during clinical care and through social networks.

Decision-making aidsThe use of scales in decision-making is related to experiences in other areas, in which their usefulness is recognised. But they can be intimidating or tedious. The population that is active in the workforce are specifically familiar with their use. There are no references in the sample studied on the specific use of scales to make decisions regarding psychiatric treatment.

Record-keeping and diary systems are evaluated as useful, but are valued more as reminders than as an aid in DM. Although some patients have experience with these types of strategies, they may perceive them more as homework to show the psychiatrist in an asymmetric relationship model.

Home plans are being used in patients attending a day hospital programme. There is familiarity with their use and they are rather used as reminders of actions to take at home, not an aid in DM.

Family and networkHealth professionals focus more on the paternalistic model, which patients do not always value positively. They value participation in DM and greater autonomy in a more collaborative provider-patient relationship.

Patients state that families are of great importance in decisions regarding treatment and want them to participate more actively. There are barriers such as ignorance and prejudices that make it difficult to feel that they are the desired support network. In other cases, family members manage to show clear support.

The relationship with insurers shows that there are barriers to timely care and continuity of care. Mental illness acts as a social determinant in health. It is necessary to work on reducing barriers to access for the completion of treatment plans.

For this population in the active workforce, work is often perceived as a factor of the illness; the impact on job performance and uncertainty about job continuity are expressed as fears. Co-workers can be seen as a support network, although some cases show that the illness can affect the relationship with other employees.

Other patients with similar experiences help in the process of learning about the illness. The relationship with other patients focuses on similarity in symptoms. It was not evidenced that patients trained in the JDM model are recognised, which serves to make the information more effective.38

Patients make little reference to friends, except those from the work environment, which may show that priority is given in providing information about the treatment of the illness to the family and that many patients exhibit social isolation.

Participants have little knowledge of patient associations, although they show a positive attitude towards them. On the other hand, the search for peers is mostly done informally during clinical care.

StigmaShame over psychiatric diagnosis and treatment leads some patients to remain silent, isolate themselves and abandon treatment. Fears of mental illness run deep, linked to stereotypes that make it difficult to accept the illness and can be related to decisions not to attend consultations and failure to comply with treatment.

Uncertainty about the course of the illness affects DM, is related to the lack of information and mentors, which seems to lead to failures in the care that the patient may choose.

There is a lack of adequate recognition of the illness by patients and their families, with moral judgements about the symptoms that make communication and understanding with others difficult, and there are prejudices, including against psychiatrists.

Patients may experience varying degrees of pain from the traumatic experience of mental illness. This makes talking about it difficult. It needs to be done in a way that prevents them from having to relive the traumatic event.

Patients recognise various forms of discrimination as a result of the illness, both due to the behaviours they exhibit and the diagnosis.

Patients avoid being reminded of the illness or thinking about the possibility of relapse, because it is considered painful or difficult to put into words. This leads to social isolation, not evaluating treatment options and participating less in DM.

ConclusionsThis is the first study in Colombia to understand how patients with mental illness make decisions about their treatment.

Conditions related to the subject, their therapeutic relationship and their environment all result in decisions being made that are not always in line with the treatment plan, such as stigma and discrimination, barriers to access and previous treatments.

Patients want to take part in decisions about their care, as part of a more informed and participatory model, with the support of their family and peer groups.

Ethical considerationsStudy approved by the ethics committee of Hospital Universitario San Ignacio. Participation was voluntary. Data that would identify cases is omitted.

Conflicts of interestThe author has no conflicts of interest to declare.

Clínica La Inmaculada and Clínica Retornar. Doctoral Programme in Clinical Epidemiology at the Faculty of Medicine, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá, Colombia, of which the author is a PhD candidate.

Please cite this article as: de la Espriella R. Toma de decisiones en pacientes psiquiátricos: un estudio cualitativo con grupos focales. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:231–238.