The term MINOCA refers to Myocardial Infarction with Non-Obstructive Coronary Arteries. The case is presented of a 54-year-old woman who, in different psychological stress situations developed characteristic symptoms of an acute myocardial infarction and increased troponins where the coronary angiography ruled out vascular involvement. In the psychological evaluation the patient described recent multiple stress factors and severe problems in childhood and early adulthood. This case is important as it concerns a woman that has no other risk factor except acute stress and a vivid traumatic history since childhood that can associate mental stress with cardiovascular disease.

El término MINOCA hace referencia al infarto de miocardio con arterias coronarias no obstruidas. A continuación, se presenta el caso de una mujer de 54 años en quien diferentes situaciones de estrés psicológico desencadenaron síntomas característicos del infarto agudo de miocardio y posteriormente elevación de troponinas, y cuya coronariografía descartó una afección vascular. En la evaluación por psiquiatría la paciente describía múltiples estresores mentales recientes y grave adversidad en la niñez y adultez temprana. Este caso es importante porque se trata de una mujer que no tiene ningún otro factor de riesgo diferente del estrés agudo y los antecedentes traumáticos vividos desde la infancia, lo que permite asociar el estrés mental con la enfermedad cardiovascular.

Myocardial infarction in the absence of obstructive coronary stenosis (MINOCA) is a term coined by DeWood et al. in 1986, when they found that 10% of patients diagnosed with acute myocardial infarction had healthy coronary arteries, with clinical and paraclinical findings of coronary syndrome, but angiography showing coronary obstruction of less than 50%.2,3

The causes of MINOCA syndrome can be grouped as follows: microvascular (myocarditis, Takotsubo syndrome, microembolism and microvascular spasm) or epicardial (thromboembolism and spasm). These are younger patients with few cardiovascular risk factors who experience some sort of psycho-emotional trigger prior to the onset of their symptoms.4

Chronic exposure to psychological stress is associated with sympathetic nervous system activation, resulting in wear and tear on the lining of the blood vessels, leading in turn to endothelial dysfunction, accelerated atherogenesis and increased incidence of cardiovascular events.5

The objective of this article was to report the case of a woman diagnosed with MINOCA associated with stressful traumatic events experienced over the course of her life and with an associated acute stress disorder.

CaseThe patient was a 54-year-old woman with technical studies in marketing, employed as a guard. She was divorced and had two children. She weighed 66 kg and was 165 cm tall. She denied any significant personal, toxicological or family medical history. She visited the accident and emergency department very early in the morning after two hours of severe, oppressive, retrosternal pain radiating to her back and both shoulders. She denied prior viral symptoms and reported that this was the first time she had ever experienced such symptoms.

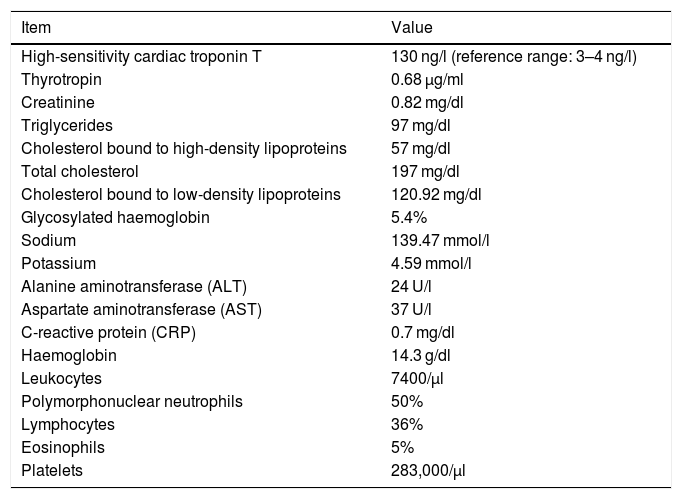

She was seen to be generally alert and oriented. Other findings were: blood pressure 159/85 mmHg; heart rate 78 bpm; oxygen saturation 98% on room air; axillary temperature 36 °C; heart sounds normal, with neither murmurs nor splitting and no S3; lung sounds normal, with no adventitious sounds; abdomen painless, with no masses on palpation; capillary filling <2 s; no oedema in the limbs; and no other abnormalities on physical examination. The patient’s paraclinical data is described in Table 1.

Paraclinical data.

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| High-sensitivity cardiac troponin T | 130 ng/l (reference range: 3–4 ng/l) |

| Thyrotropin | 0.68 μg/ml |

| Creatinine | 0.82 mg/dl |

| Triglycerides | 97 mg/dl |

| Cholesterol bound to high-density lipoproteins | 57 mg/dl |

| Total cholesterol | 197 mg/dl |

| Cholesterol bound to low-density lipoproteins | 120.92 mg/dl |

| Glycosylated haemoglobin | 5.4% |

| Sodium | 139.47 mmol/l |

| Potassium | 4.59 mmol/l |

| Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) | 24 U/l |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) | 37 U/l |

| C-reactive protein (CRP) | 0.7 mg/dl |

| Haemoglobin | 14.3 g/dl |

| Leukocytes | 7400/μl |

| Polymorphonuclear neutrophils | 50% |

| Lymphocytes | 36% |

| Eosinophils | 5% |

| Platelets | 283,000/μl |

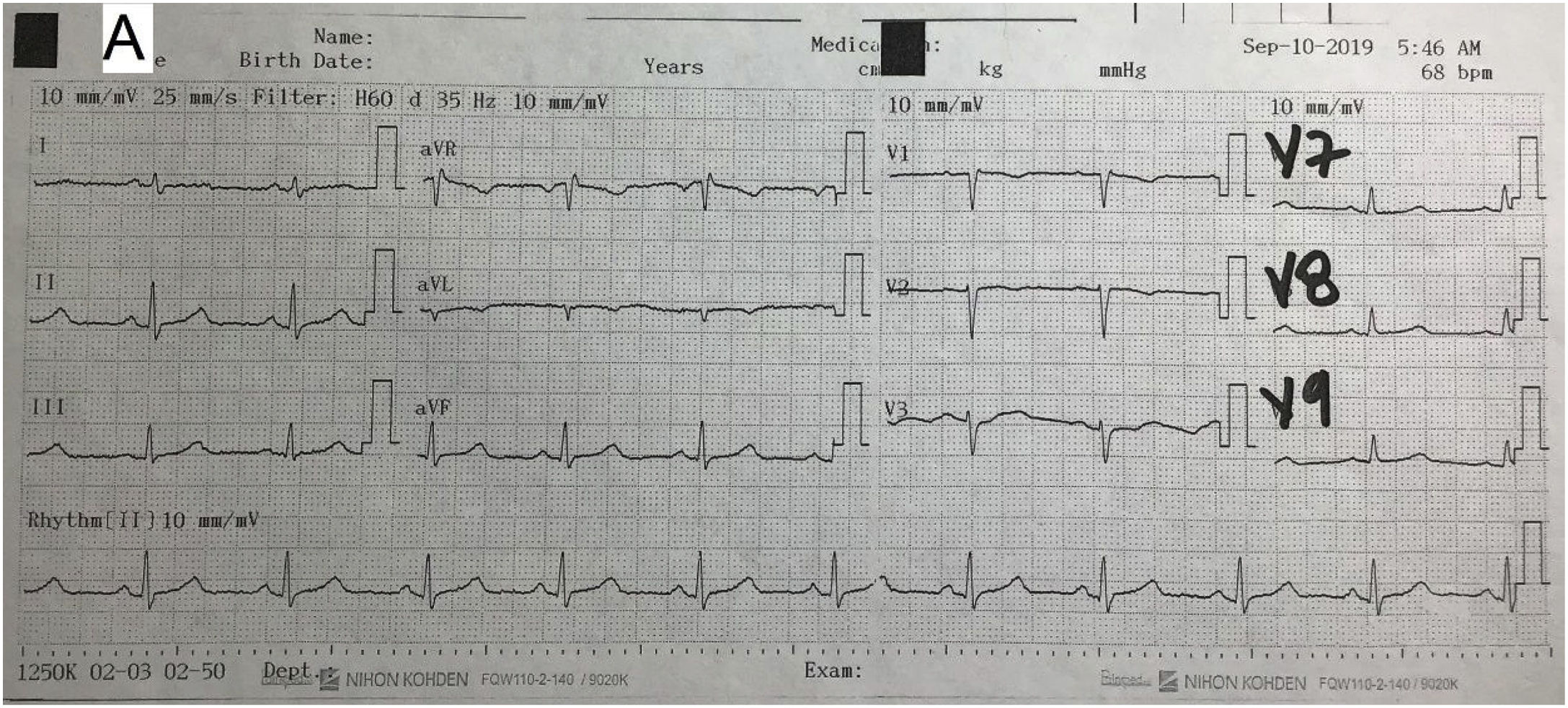

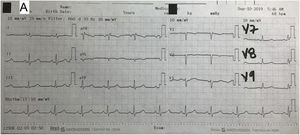

A chest X-ray showed no mediastinal enlargement, no increased cardiothoracic ratio, no pleural abnormalities and no pneumoperitoneum. An electrocardiogram showed a sinus rhythm, normal axis, heart rate 70 bpm, PR interval 120 ms, QRS interval 100 ms, ST segment with no elevation or depression and T wave inversion with asymmetrical branches in leads V1–V2 < 0.1 mV and corrected QT interval of 420 ms. Follow-up electrocardiograms showed no changes compared to the first electrocardiogram (Fig. 1).

The patient was diagnosed with Killip class I acute coronary syndrome with no ST elevation, and treatment was started with acetylsalicylic acid 300 mg, clopidogrel 600 mg, atorvastatin 80 mg, enoxaparin 60 mg and metoprolol 50 mg.

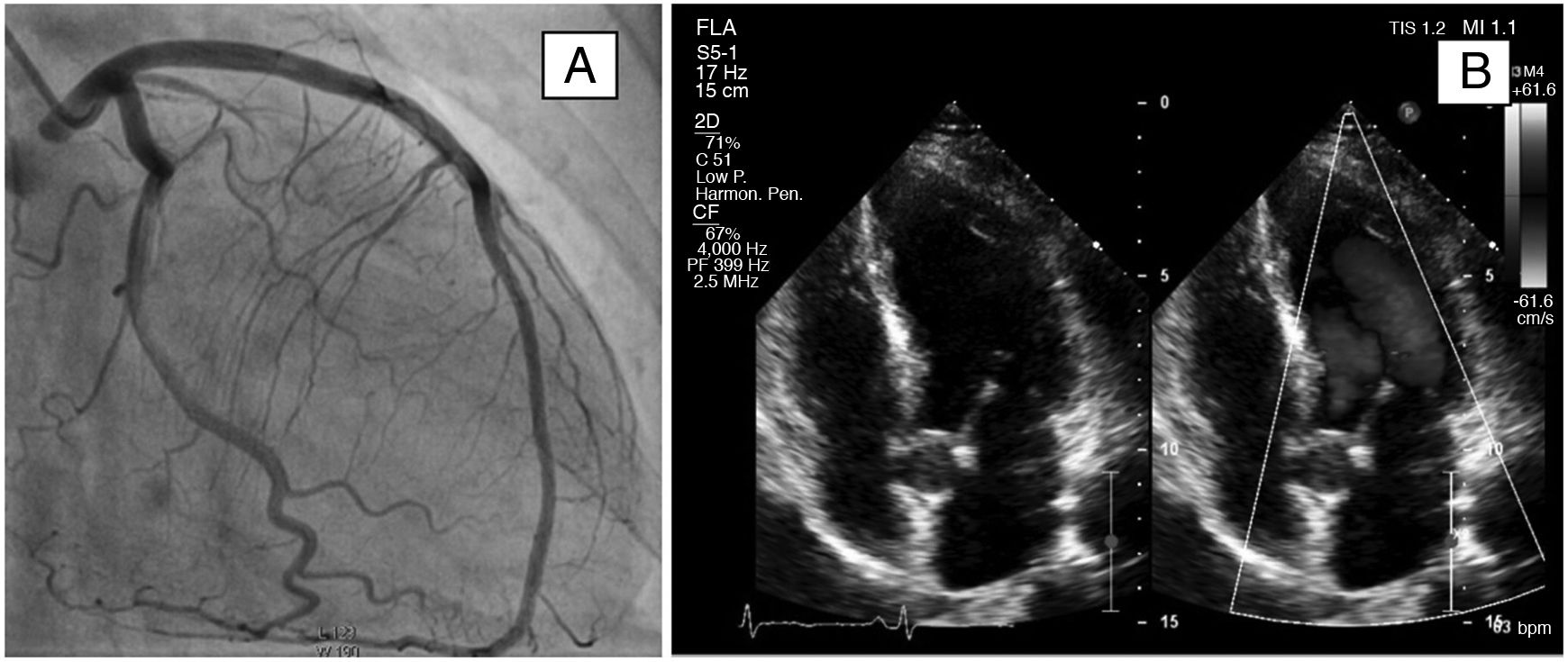

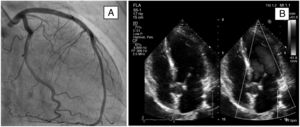

A transthoracic echocardiogram showed diffuse hypokinesia, evident in the medial and apical septal segments. Ejection fraction was estimated at 50%. Left ventricular systolic function was slightly reduced (mitral annular plane systolic excursion [MAPSE]: 12 mm). Systolic function was preserved (tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion [TAPSE] 17 mm). No thrombi or intracavitary masses were observed. The pericardium had normal characteristics, with no effusion. Pulmonary systolic blood pressure was estimated at 29 mmHg (Fig. 2).

On a coronary angiogram, the left main trunk, the anterior descending artery and the dominant circumflex artery lacked obstructive lesions. The non-dominant right coronary artery was rudimentary with no lesions (Fig. 2).

The patient was transferred to coronary care with a diagnosis of MINOCA.

Cardiology ruled out cardiometabolic risk, but did find traits of anxiety and excessive stress in the past few weeks, and therefore consulted with a liaison psychiatrist.

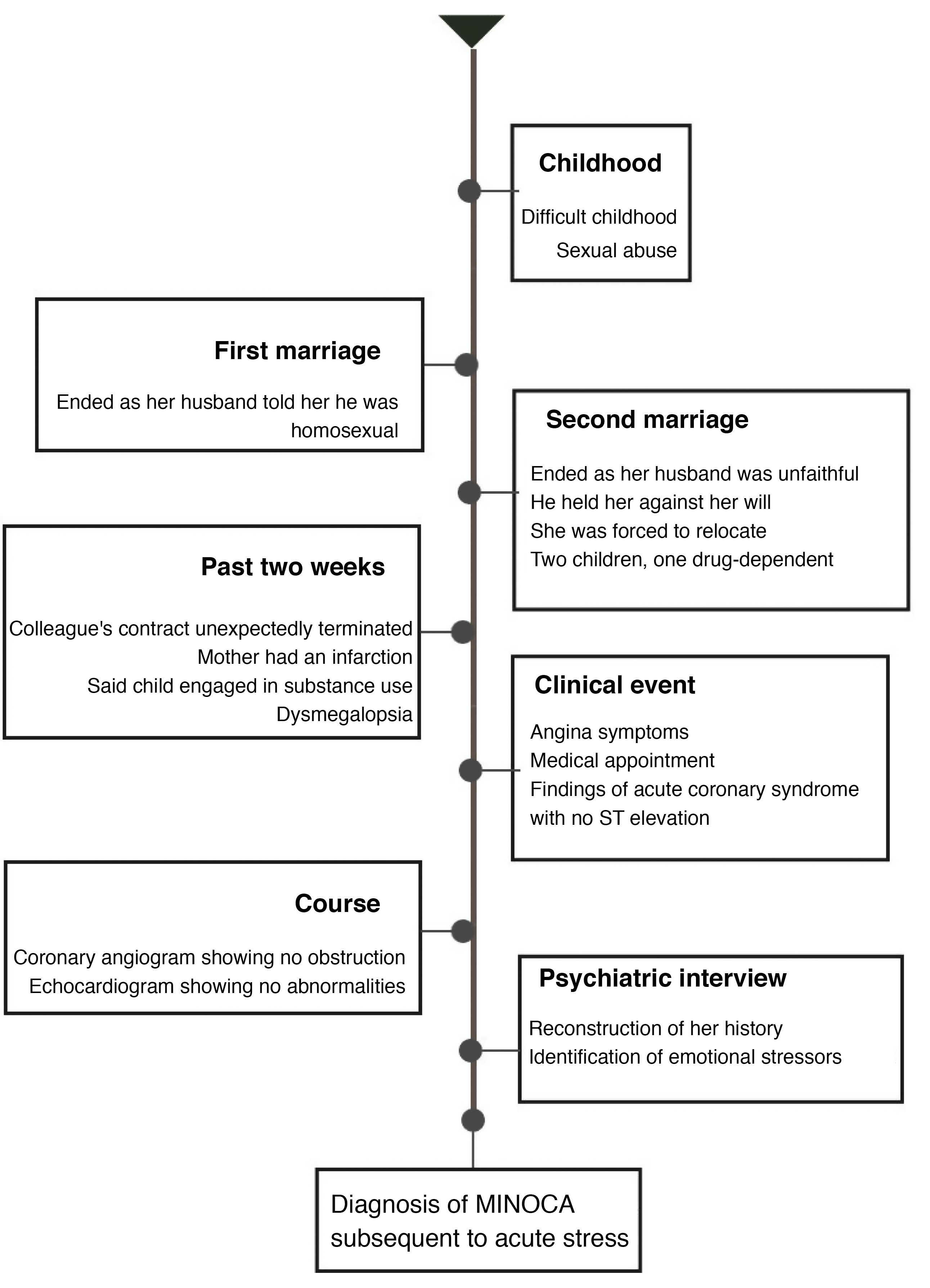

During the interview, the patient mentioned severe stress in the past two months: her sister had been diagnosed with cancer, her mother had become seriously ill, her son had been found to be using substances and she had slept poorly in the past week. On the day of the infarction, she had received a call from her colleague whose employment contract was terminated, and she felt that she was in danger of being dismissed. “Despite all my difficulties, I am brave and a fighter”, she said. “I kept on bottling it up until I couldn’t take it anymore.” She added, “I felt as though my body had swelled up almost to the point of bursting, then as though I could float …” This corresponds to dysmegalopsia, a dissociative symptom often found in patients with panic attacks, acute stress and dissociative disorders. The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)-14 was administered, revealing a high level of stress in the past month.

The patient reported a history of childhood sexual abuse, as well as problems in her relationship with her first husband, who had told her that he was homosexual. Her second husband had been unfaithful to her; he had also held her against her will for a few days and threatened to kill her. She had been forced to relocate to another city with her two children, lost her previous job as a merchandiser and had to deal with serious economic problems as a result.

Mental examination found her to be alert and oriented, with normal attention capacities. Affective modulation was resonant. Her speech was normal, with coherent logical thinking and anxious ideas in relation to her current situation. She did not demonstrate any depressive, suicidal or delusional ideation. No sensory processing disorders were identified. Her memory was preserved and her judgement appropriate. She showed positive prospection with regard to her physical recovery and suitable introspection.

The patient reported that, years earlier, she had seen a psychologist on three occasions, but had not improved. Psychiatry conducted a therapeutic conversation in which she was given a didactic explanation of the mind–body connection and encouraged to start individual outpatient psychotherapy. The mental disorder that accounts for her symptoms is an adjustment disorder, which according to the DSM-5 is a trauma and stress-related disorder. No psychopharmaceuticals were formulated6 (Fig. 3).

Five weeks later, outpatient cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed normal ventricular morphology, with segmental mobility and normal wall thickness, and preserved systolic and diastolic function, with no myocardial fibrosis or signs of an infiltrative or inflammatory condition and no signs of myocardial oedema or impaired myocardial perfusion.

DiscussionThe prevalence of MINOCA is around 6% of all patients with acute myocardial infarction; most are women younger than those with coronary obstruction. It has also been reported to have a higher prevalence in black, Maori and “Hispanic” populations with no history of angina or cardiovascular risk factors.7,8

A study by Lima et al.,2 conducted in 569 patients, showed a 23% reduction in coronary blood flow after patients had endured mental stress, amounting to a 78% increase in the incidence of cardiovascular events in affected persons (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.78; 95% confidence interval [95%CI] = 1.15–2.76). This supports the hypothesis of mental stress as a mechanism causing endothelial dysfunction.

Chronic stress limits endothelial relaxation and accelerates the atherogenic process by increasing the rate of endothelial damage and reducing nitric oxide in the coronary arteries, even in people without cardiovascular risk factors. Hence, stress triggers adrenergic sympathetic regulators, resulting in increased heart rate, blood pressure, cortisol, and peripheral arterial constriction as well as changes in the immune response, particularly T lymphocytes.9

Many studies have investigated the association between adverse childhood experiences and cardiometabolic risk, paying attention to the relationship between abuse in childhood and morbidity and mortality in adulthood. Felitti et al. found that childhood exposure to sexual, physical, and emotional abuse was associated with multiple diseases in adulthood, including cardiovascular disease. In a study of 66,798 women, Rich-Edwards et al. found sexual abuse in childhood to be associated with 46%–56% higher subsequent cardiovascular risk.10–12

Thirty years ago, McEwen proposed the concept of allostatic load, referring to the cumulative effects of stressful experiences in everyday life and the price that neurobiological systems will pay when physiological response overwhelms individual coping mechanisms. Physiological response to psychosocial stressors has been associated with the onset, maintenance and exacerbation of many and varied types of disease that may reduce life expectancy, such as cardiovascular disease.13,14

ConclusionsThis study reports a clinical case of MINOCA associated with acute stress of mental origin in a women with a history of multiple traumatic events having occurred over the course of her life and a Framingham cardiovascular risk score of 8%, pointing to a need to consider acute psychological stress to be a risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

MethodsA report of a clinical case seen at a private cardiovascular disease clinic in Medellín, Colombia, and a non-systematic review of the relevant literature. The patient signed an informed consent form after the use of her clinical information for academic purposes was explained and the confidentiality of her data was guaranteed. The CARE guidelines were taken into account in the preparation thereof.1

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Londoño-Gómez F, Romero-Cortes A, Restrepo D. Mujer de 54 años con diagnóstico de MINOCA y estrés psicológico: a propósito de un caso. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2022;51:71–75.