Every 40s, one person in the world commits suicide. As such, suicide is considered a public health problem, and prior suicide attempt is one of the risk factors associated with completed suicide. Despite the strategies implemented and the studies carried out, in Colombia suicide figures are on the rise, more markedly in the economically active population.

ObjectiveTo identify the sociodemographic, family, personal, economic and religious factors associated with suicide attempt in patients of productive age (18–62 years old) in a mental health institution in Bogota, Colombia.

MethodsAn analytical prevalence study was conducted at the Nuestra Señora de la Paz mental health clinic in Bogota. To explore the relationship between the factors described and suicide attempt, a review of 350 medical records of the selected population was carried out.

ResultsIn total, 37.7% of the sample presented a suicide attempt. Associations were found between the suicide attempt and higher education than primary school (PR=0.47 [0.23−0.97]), no economic income (PR=1.72 [1.13−2.61]), no partner (PR=2.10 [1.33−3.32]), alcohol consumption (P=.045), hallucinogen use (PR=2.39 [0.97−3.43]) and the presence of personality disorder (PR=1.93 [1.11−3.34]).

ConclusionsThe results of the study are similar to those previously described in other studies around the world. There is a need to recognise and address various factors associated with suicide attempt in depressed patients in order to implement promotion and prevention actions, early identification and specific interventions that have an impact on the numbers of completed suicide in the country.

En el mundo, cada 40 segundos una persona se quita la vida; el suicidio se considera un problema de salud pública, y el intento de suicidio previo es uno de los factores de riesgo relacionados con suicidio consumado. A pesar de las estrategias implementadas y los estudios realizados, en Colombia las cifras de suicidio van en ascenso, de manera más marcada en la población económicamente activa.

ObjetivoIdentificar los factores sociodemográficos, familiares, personales, económicos y religiosos asociados con el intento suicida en pacientes con trastorno depresivo en edad productiva (18–62 años), en una institución de salud mental en Bogotá, Colombia.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio de prevalencia analítica en la Clínica de Nuestra Señora de la Paz, de Bogotá; para explorar la relación entre los factores descritos y el intento suicida, se realizó una revisión de 350 historias clínicas de la población seleccionada.

ResultadosEl 37,7% de la muestra presentó intento de suicidio. Se encontraron asociaciones entre el intento de suicidio y la formación superior a primaria (RP=0,47 [0,23–0,97]), no recibir ingresos (RP=1,72 [1,13–2,61]), no tener pareja (RP=2,10 [1,33–3,32]), el consumo de alcohol (P=,045), el consumo de alucinógenos (RP=2,39 [0,97–3,43]) y la presencia de trastorno de personalidad (RP=1,93 [1,11–3,34]).

ConclusionesLos resultados del estudio son similares a los descritos previamente en el mundo. Es necesario reconocer y abordar diversos factores asociados con el intento de suicidio en pacientes depresivos para desplegar acciones de promoción y prevención, identificación temprana e intervenciones específicas que impacten en las cifras de suicidio consumado en el país.

Every year more than 800,000 people worldwide take their own lives; that means one death every 40s.1 According to the figures of the Colombian National Institute of Legal Medicine and Forensic Sciences, the death rate by suicide in 2017 was 5.7/100,000 population. That same year, the city of Bogotá registered a death rate by suicide of 4.3/100,000 population.2 Depression is the main diagnosis related to deaths by suicide and this is more common in women than in men.3 Between 30% and 60% of suicides are preceded by a previous attempt.4 The rate of completed suicide is 100 times higher in the roughly 14% of patients who have attempted to end their life at some point.5

Of the cases of suicide in Colombia, 44.7% are people aged 20–39.6 Patients with depression do not only have the moral pain that accompanies the disorder. Both the family nucleus and the community are also affected, added to the burden of the disease due to the related disability and potential associated suicide.

A recent World Health Organisation (WHO) report states that depression and anxiety disorders represent productivity losses of 1 billion dollars7 or one billion in Colombian pesos.

In Colombia, the largest proportion of the workforce is in the 18–62 age group,8 while the retirement age is 57 for women and 62 for men.9

Attempted suicide has been reported as the main risk factor for completed suicide4; demographic, social, family, personal, economic and religious elements have been identified around this which may be related to the fatal outcome.

In a case-control study carried out in Bogotá, it was found that the factors associated with patients' suicidal ideation and attempted suicide were: being aged 31 or over; being a student or not having an occupation; having a history of more than two previous suicide attempts; lack of resolution or worsening of the conflicts that triggered the event that required psychiatric consultation; and family dysfunction.4 In Ibagué, Colombia, a descriptive study identified the stressful life events in patients who had attempted suicide. In 2014, 34.8% referred to dysfunction with parents; 49.6% dysfunction with their partner; and 10.1%, social isolation. The analysis in this study enabled the population to be characterised, and other variables such as unemployment and mental illness history were included.8

Early identification of risk factors and the strengthening of protective factors can reduce the suicide rate and decrease its consequences for the environment of the affected person. To achieve this objective, in 2013 the WHO adopted the “Comprehensive Mental Health Action Plan 2013–2020”, which seeks the implementation of strategies for the promotion and prevention of psychiatric diseases.9 In Colombia, figures from the Legal Medicine institute show that from 2012 to 2018, 1878 people committed suicide in Bogotá, 268 per year; in that same period of time, 14,564 people attempted suicide, including 2811 in 2016 and 2351 in 201710; a significant proportion of suicide attempts ended up as completed suicides.

In Japan, in seeking to identify some of the factors associated with suicidal behaviour, it was found that the most common were health problems, followed by family, financial, work-related and emotional difficulties. After determining these factors and implementing early intervention, 10 years later suicides had decreased considerably among men in their fifties.11

Although the risk factors for and protective factors against suicide are well known in the scientific community, suicide mortality rates have remained unchanged over time in Bogotá, in Colombia and worldwide. Further in-depth research and the conducting of new studies in this area could help reinforce current knowledge and expand the scope for the creation of prevention strategies.

This study aims to identify the combination of sociodemographic and clinical factors related to suicide attempts in economically active depressed patients from a psychiatry referral centre in Bogotá, Colombia, to contribute to the creation of early intervention strategies and so help reduce the likelihood of suicide and its associated negative effects.

MethodsWe designed an analytical prevalence study to assess the factors associated with attempting suicide and estimate their prevalence in patients diagnosed with depressive disorder.

The target population were patients aged 18–62 with depressive disorder treated at the clinic, Clínica Nuestra Señora de la Paz, in the city of Bogotá, Colombia from January to December 2018.

The sample size was calculated accepting an alpha risk of 0.05 and a beta risk of 0.2 in a two-tailed contrast; 344 subjects were required to detect the statistically significant difference between two proportions.12 A loss to follow-up rate of 10% was estimated.

In accordance with the sample size calculation, 350 patients with a diagnosis of depressive disorder were selected; the investigators collected and analysed the data through the review of the subjects' medical records. We created a database without identifying information and labelled with codes to guarantee confidentiality. The selection of patients was managed systematically.

This research project was approved by the Clínica Nuestra Señora de la Paz Independent Ethics Committee.

The inclusion criteria were: men aged 18–62 and women aged 18–57 with a diagnosis of depressive disorder according to the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases and patients seen in the emergency and admissions departments of Clínica La Paz de Bogotá from January to December 2018. Patients with incomplete or discordant medical records were excluded.

The variables included in the analysis were attempted suicide, considered as dependent variable, and as independent variables: gender, age, origin, highest educational qualification obtained, healthcare scheme, psychiatric history, occupation, marital status, comorbidities, number of children, religion, stressful life event, adherence to treatment, smoking, alcohol consumption measured on an ordinal scale (no, occasional, moderate and high), consumption of psychoactive substances, type of substance and other associated psychiatric disorders.

The prevalence was determined as the proportion, expressed as a percentage, of the total population in the last year. For the univariate analysis of the qualitative variables, relative and absolute frequencies were reported. For the quantitative variables, normality was explored by means of the Kolmogorov-Smirnoff statistic with a significance level of 5% (P<.05); the variables with non-normal distribution were reported as measures of central tendency, the median and as measure of dispersion, the minimum and maximum values. Bivariate analysis was performed to determine the association between the factors and the suicide attempt. The nominal dichotomous and polytomous variables were analysed by means of contingency tables and the χ2 test or the comparison of means or medians, as appropriate. Lastly, a multivariate analysis was performed with a logistic regression model, which included the statistically significant independent variables, in order to analyse their contribution to the suicide attempt.

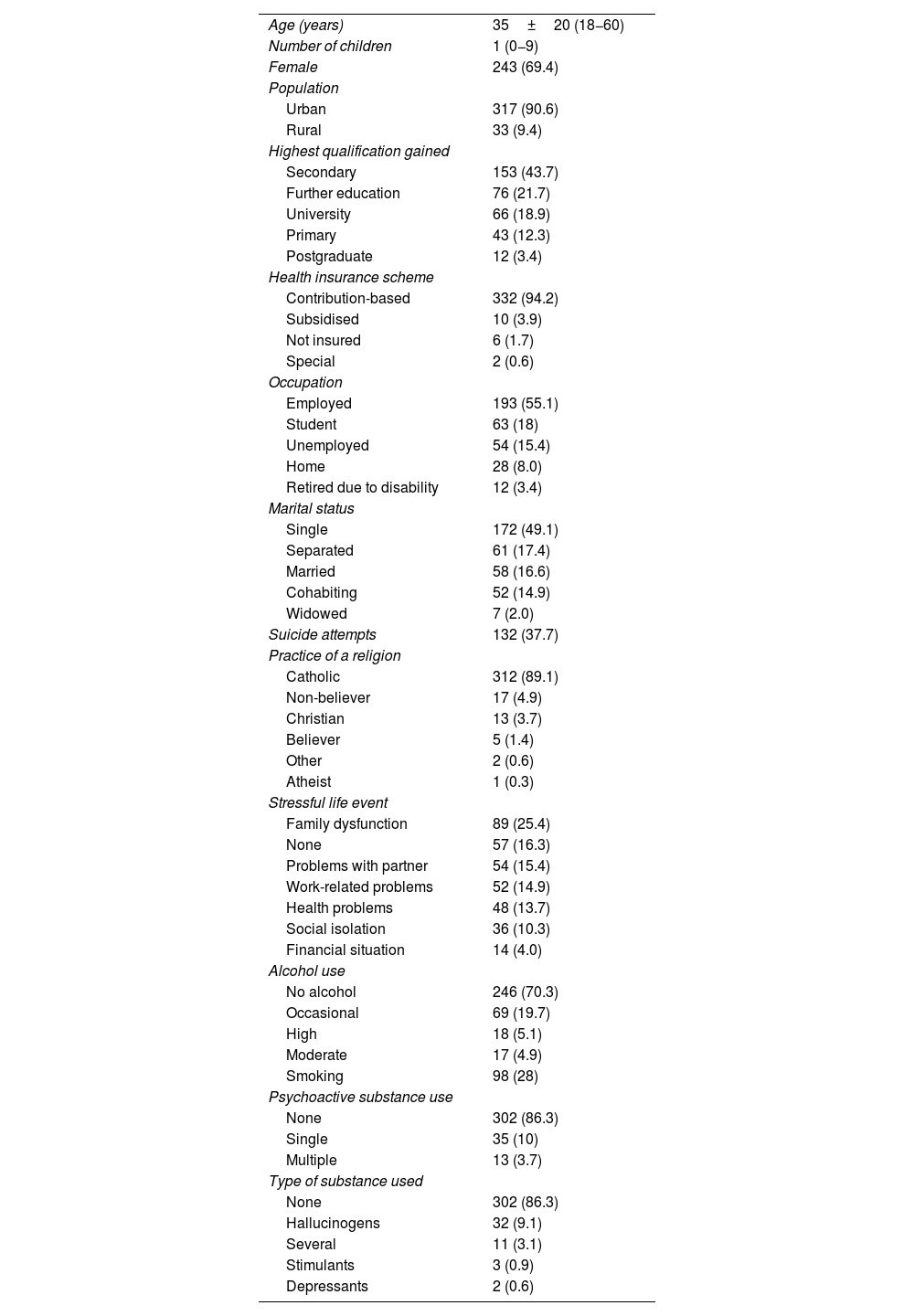

ResultsThe studied sample consisted of 350 patients aged 18–62 with a diagnosis of depressive disorder; 50% of the patients were under the age of 35, and the ratio of males to females was 4:10. The patients' sociodemographic and lifestyle variables are shown in Table 1.

Sociodemographic characterisation of the sample.

| Age (years) | 35±20 (18−60) |

| Number of children | 1 (0−9) |

| Female | 243 (69.4) |

| Population | |

| Urban | 317 (90.6) |

| Rural | 33 (9.4) |

| Highest qualification gained | |

| Secondary | 153 (43.7) |

| Further education | 76 (21.7) |

| University | 66 (18.9) |

| Primary | 43 (12.3) |

| Postgraduate | 12 (3.4) |

| Health insurance scheme | |

| Contribution-based | 332 (94.2) |

| Subsidised | 10 (3.9) |

| Not insured | 6 (1.7) |

| Special | 2 (0.6) |

| Occupation | |

| Employed | 193 (55.1) |

| Student | 63 (18) |

| Unemployed | 54 (15.4) |

| Home | 28 (8.0) |

| Retired due to disability | 12 (3.4) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 172 (49.1) |

| Separated | 61 (17.4) |

| Married | 58 (16.6) |

| Cohabiting | 52 (14.9) |

| Widowed | 7 (2.0) |

| Suicide attempts | 132 (37.7) |

| Practice of a religion | |

| Catholic | 312 (89.1) |

| Non-believer | 17 (4.9) |

| Christian | 13 (3.7) |

| Believer | 5 (1.4) |

| Other | 2 (0.6) |

| Atheist | 1 (0.3) |

| Stressful life event | |

| Family dysfunction | 89 (25.4) |

| None | 57 (16.3) |

| Problems with partner | 54 (15.4) |

| Work-related problems | 52 (14.9) |

| Health problems | 48 (13.7) |

| Social isolation | 36 (10.3) |

| Financial situation | 14 (4.0) |

| Alcohol use | |

| No alcohol | 246 (70.3) |

| Occasional | 69 (19.7) |

| High | 18 (5.1) |

| Moderate | 17 (4.9) |

| Smoking | 98 (28) |

| Psychoactive substance use | |

| None | 302 (86.3) |

| Single | 35 (10) |

| Multiple | 13 (3.7) |

| Type of substance used | |

| None | 302 (86.3) |

| Hallucinogens | 32 (9.1) |

| Several | 11 (3.1) |

| Stimulants | 3 (0.9) |

| Depressants | 2 (0.6) |

The values express mean±standard deviation (range), mean (range) or n (%).

In 58% of the sample there was no family psychiatric history and 53.7% had some non-psychiatric medical illness. Of the associated psychiatric disorders, the most common was personality disorder (14.6%), followed by anxiety disorder (11.7%); the least common was schizophrenia (0.6%). With regard to adherence to medical treatment, 38.9% of patients were classified as adherent to treatment, 38.9% as non-adherent and 26.9% were not on any drug treatment.

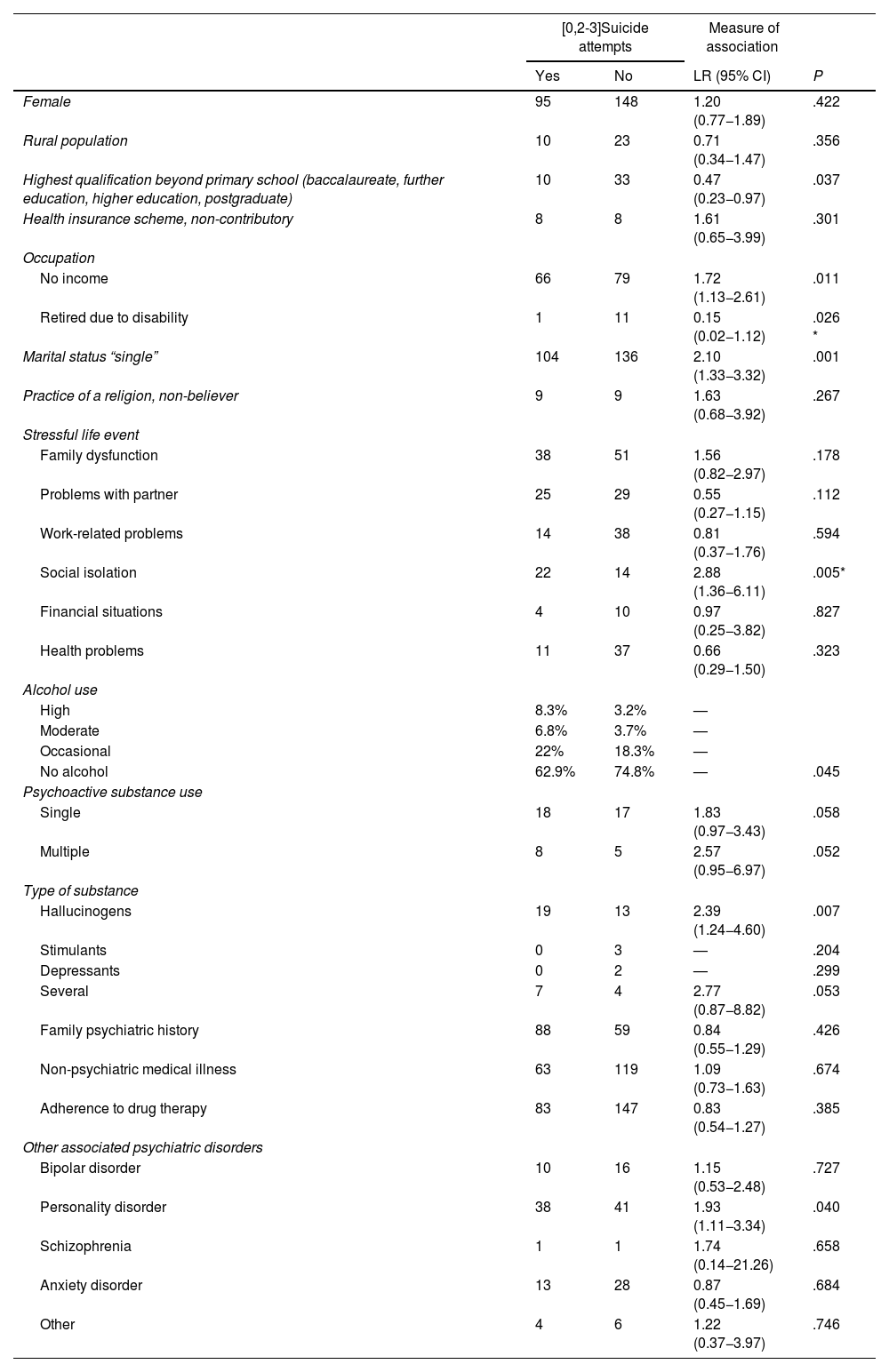

The prevalence of suicide attempts among patients with depression who attended the Clínica Nuestra Señora de la Paz in 2018 was 37.7%, higher in women than in men (39.1% versus 34.6%). Analysing the association between sociodemographic variables and attempted suicide, no significant differences were found for gender, type of population, health insurance scheme or being retired due to disability (Table 2).

Association of variables with suicide attempt in patients with major depression (n=350).

| [0,2-3]Suicide attempts | Measure of association | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | LR (95% CI) | P | |

| Female | 95 | 148 | 1.20 (0.77−1.89) | .422 |

| Rural population | 10 | 23 | 0.71 (0.34−1.47) | .356 |

| Highest qualification beyond primary school (baccalaureate, further education, higher education, postgraduate) | 10 | 33 | 0.47 (0.23−0.97) | .037 |

| Health insurance scheme, non-contributory | 8 | 8 | 1.61 (0.65−3.99) | .301 |

| Occupation | ||||

| No income | 66 | 79 | 1.72 (1.13−2.61) | .011 |

| Retired due to disability | 1 | 11 | 0.15 (0.02−1.12) | .026 * |

| Marital status “single” | 104 | 136 | 2.10 (1.33−3.32) | .001 |

| Practice of a religion, non-believer | 9 | 9 | 1.63 (0.68−3.92) | .267 |

| Stressful life event | ||||

| Family dysfunction | 38 | 51 | 1.56 (0.82−2.97) | .178 |

| Problems with partner | 25 | 29 | 0.55 (0.27−1.15) | .112 |

| Work-related problems | 14 | 38 | 0.81 (0.37−1.76) | .594 |

| Social isolation | 22 | 14 | 2.88 (1.36−6.11) | .005* |

| Financial situations | 4 | 10 | 0.97 (0.25−3.82) | .827 |

| Health problems | 11 | 37 | 0.66 (0.29−1.50) | .323 |

| Alcohol use | ||||

| High | 8.3% | 3.2% | — | |

| Moderate | 6.8% | 3.7% | — | |

| Occasional | 22% | 18.3% | — | |

| No alcohol | 62.9% | 74.8% | — | .045 |

| Psychoactive substance use | ||||

| Single | 18 | 17 | 1.83 (0.97−3.43) | .058 |

| Multiple | 8 | 5 | 2.57 (0.95−6.97) | .052 |

| Type of substance | ||||

| Hallucinogens | 19 | 13 | 2.39 (1.24−4.60) | .007 |

| Stimulants | 0 | 3 | — | .204 |

| Depressants | 0 | 2 | — | .299 |

| Several | 7 | 4 | 2.77 (0.87−8.82) | .053 |

| Family psychiatric history | 88 | 59 | 0.84 (0.55−1.29) | .426 |

| Non-psychiatric medical illness | 63 | 119 | 1.09 (0.73−1.63) | .674 |

| Adherence to drug therapy | 83 | 147 | 0.83 (0.54−1.27) | .385 |

| Other associated psychiatric disorders | ||||

| Bipolar disorder | 10 | 16 | 1.15 (0.53−2.48) | .727 |

| Personality disorder | 38 | 41 | 1.93 (1.11−3.34) | .040 |

| Schizophrenia | 1 | 1 | 1.74 (0.14−21.26) | .658 |

| Anxiety disorder | 13 | 28 | 0.87 (0.45−1.69) | .684 |

| Other | 4 | 6 | 1.22 (0.37−3.97) | .746 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; LR: likelihood ratio.

Among personal variables, no difference was found between patients who declared themselves believers and those who did not. Among stressful life events, a relationship was found between social isolation and suicide attempts. Alcohol consumption was also associated with attempted suicide.

No significant differences were found between patients who consumed a single psychoactive substance or multiple substances. However, an association was found with the use of hallucinogens; users of this type of substance had twice the risk of attempting suicide.

Among the other psychiatric disorders, patients who also suffered from personality disorder were at 1.9 times increased risk of attempting suicide.

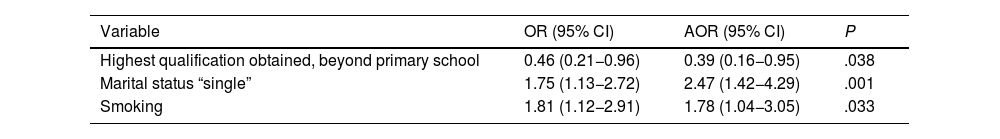

We carried out a multivariate analysis, including the set of significantly associated variables (P<.05) and those close to that value ranked in order of associated factors. The multivariate model explained 10% of the outcome of interest. We determined that the factors which in combination explained attempted suicide were having higher than primary education, not having a partner and smoking (Table 3).

Logistic regression model.

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest qualification obtained, beyond primary school | 0.46 (0.21−0.96) | 0.39 (0.16−0.95) | .038 |

| Marital status “single” | 1.75 (1.13−2.72) | 2.47 (1.42−4.29) | .001 |

| Smoking | 1.81 (1.12−2.91) | 1.78 (1.04−3.05) | .033 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; OR: crude odds ratio; AOR: adjusted odds ratio.

In this study, we have described the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of patients diagnosed with depressive disorder treated at the Clínica Nuestra Señora de la Paz from January to December 2018 and we have looked for any associations with suicide attempts. The prevalence of suicide attempts in this sample was 37.7%. We found that most patients diagnosed with depression were not admitted to the hospital for suicide risk but for other clinical reasons, such as psychotic symptoms, survival risk and comorbidities.

Smoking and psychoactive substance use were variables considered as confounding, as associations with suicide attempts were detected before statistical control, but after controlling for them in the logistic regression model, they disappeared. Smoking, with an interaction effect, was identified as a risk factor for the outcome.

Women were found to have a higher percentage of suicide attempts, in line with previous studies in Colombia.5 However, there was no significant difference between genders and the outcome being studied.13 No significant difference was found between the patients' different health insurance schemes or between rural and urban populations. One explanation for this phenomenon may be the location of the mental health unit and the characteristics of the patients in a hospital whose coverage is more aimed at an urban population and a contributory scheme.

The results suggest that patients without a partner and with middle-level education have a higher risk of suicide attempts, which is in line with findings in other Latin American countries.13,14 However, it should be noted that having “single” marital status is not equivalent to living without a partner, so new hypotheses may be generated about this finding, as the quality of the data collected in this study limits the analysis.

Patients with children show differences in outcome compared to those without children, in line with reports from around the world,15 and it has been established that having children is a protective factor. Unlike the findings of other studies, no associations were found between practising a religion and the outcome of interest.15 The stressful life event associated with the suicide attempt was the social isolation reported by the patients, a finding already described in other studies in Colombia.8

As regards alcohol use, an association and linear tendency were found with the suicide attempt; despite not having an objective measurement of this variable due to the retrospective nature of the data collection, the association is present in the results, which may also reflect the differential behaviour of the dual disease. Patients who were users of a single substance or multiple psychoactive substances had a higher rate of suicide attempts. Patients who consumed hallucinogens, in particular, were at double the risk of attempting suicide, as found in other countries8,14; that can be explained by mental, emotional and biological changes related to their substance use.

No significant difference was found between other non-psychiatric illnesses and adherence to drug treatment. This situation in a mental health unit in the capital is similar to that described in studies from other parts of the country and the world.8,13

An interesting finding was the association of attempted suicide with being retired due to disability; we did not find much data on this area in the publications we reviewed. New research hypotheses should be generated around this finding, as it is a growing vulnerable population with a high demand for mental health care.

One of the study's strengths is the sample size, which exceeded the number indicated in the calculation. Another strength was the methods used to control bias, such as double typing and data verification. Researching in a mental health unit representative of the population with psychiatric illness can increase confidence in the results obtained.

The study's limitations include those inherent to relying on the material recorded in the medical records, the fact that the population was purely from one clinic in the capital of Colombia, and the retrospective nature of the data, all of which make it difficult to generalise the findings.

ConclusionsWe found that suicide attempts among the depressed patients in our sample were associated with factors such as having an educational level beyond primary school, having no income, not having a partner, being retired due to disability, alcohol use, social isolation, use of hallucinogens and suffering from a personality disorder. We need to structure healthcare models, including intervention and health promotion and prevention schemes designed around these variables, to create effective schemes that are more fit-for-purpose.

Conflicts of interestAlexie Vallejo Silva has received fees as a speaker and consultant from Janssen, Sanofi, Lundbeck and Pfizer. He also received fees from the Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud (IETS) [Institute of Technological Evaluation in Health].