The crisis situation generated by COVID-19 and the measures adopted have generated social changes in the normal dynamics of the general population and especially for health workers, who find themselves caring for patients with suspected or confirmed infection. Recent studies have detected in them depression and anxiety symptoms and burnout syndrome, with personal and social conditions impacting their response capacity during the health emergency. Our aim was to generate recommendations for the promotion and protection of the mental health of health workers and teams in the first line of care in the health emergency due to COVID-19.

MethodsA rapid literature search was carried out in PubMed and Google Scholar, and an iterative expert consensus and through electronic consultation, with 13 participants from the areas of psychology, psychiatry and medicine; the grading of its strength and directionality was carried out according to the international standards of the Joanna Briggs Institute.

ResultsThirty-one recommendations were generated on self-care of health workers, community care among health teams, screening for alarm signs in mental health and for health institutions.

ConclusionsThe promotion and protection activities in mental health to face the health emergency generated by COVID-19 worldwide can include coordinated actions between workers, health teams and health institutions as part of a comprehensive, community care, co-responsible and sustained over time.

La situación de crisis generada por la COVID-19 y las medidas adoptadas han generado cambios sociales en las dinámicas normales de la población general y en especial para los trabajadores de la salud, que se encuentran en atención del paciente con infección sospechada o confirmada. Estudios recientes han detectado en ellos síntomas depresivos y ansiosos y síndrome de burnout, afecciones personales y sociales que alteran su capacidad de respuesta durante la emergencia sanitaria. El objetivo es generar recomendaciones de promoción y protección de la salud mental de los trabajadores y equipos de salud dispuestos como primera línea de atención en la emergencia sanitaria por COVID-19.

MétodosSe realizó una búsqueda rápida de literatura en PubMed y Google Scholar, y un consenso de expertos iterativo y mediante consulta electrónica, con 13 participantes de las áreas de psicología, psiquiatría y medicina; la gradación de su fuerza y direccionalidad se realizó según las normas internacionales del Joanna Briggs Institute.

ResultadosSe generaron 31 recomendaciones sobre el autocuidado del trabajador de la salud, el cuidado comunitario entre los equipos de salud, el cribado de signos de alarma en salud mental y para las instituciones sanitarias.

ConclusionesLas actividades de promoción y protección en salud mental para el afrontamiento de la emergencia sanitaria generada por la COVID-19 en todo el mundo pueden abarcar acciones articuladas entre el trabajador, los equipos de salud y las instituciones sanitarias como parte de un cuidado integral, comunitario, corresponsable y sostenidas en el tiempo.

The SARS-Cov-2 infection that causes COVID-19 has so far caused 13,200,550 infections and 575,178 deaths1 and was classified as a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020.2 This disease causes a mild to moderate respiratory condition, with spontaneous recovery in most cases. Groups at risk of symptom complications and with a higher risk of mortality are considered to be the elderly and those with underlying medical problems, such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, chronic respiratory diseases and cancer.3 However, little is known about the disease, which has made it necessary to rapidly and constantly generate new clinical information for its treatment, to take public health measures such as social distancing and quarantines, and to adapt new care spaces for the critical care of complicated cases, which represents a challenge for health systems in their infrastructure and human talent.

Regarding the effects on mental health, understood as psychological, emotional and social abilities and capacities,4 the crisis situation generated by COVID-19 and the measures adopted have generated social changes in the normal dynamics of the general population that have led to increased acute stress, frustration, loneliness, substance abuse, insomnia, loss of control due to high uncertainty, and even the appearance of depressive and anxious symptoms.5,6 In health workers who care for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, recent studies have detected the appearance of depressive and anxious symptoms and burnout syndrome,7–11 as well as personal and social impacts,12 which could affect their response capacity during the pandemic.13

These conditions could not only be an immediate and transitory response, but also have medium and long-term effects, as was found in a rapid systematic review14 which retrospectively looked at the experience of health professionals who faced the Ebola outbreak, the influenza A (H1N1) pandemic, and the epidemics produced by the severe acute respiratory syndrome and the Middle East respiratory syndrome, identifying effects after the health emergency has been overcome in the medium term such as feeling greater stigmatisation, more anger, annoyance, fear, frustration, guilt, helplessness, isolation, loneliness, nervousness, sadness and worry, and less happiness compared to the general population, and they were found to require more time to overcome the experience. In the long term, alcohol abuse and dependence, symptoms of depression and post-traumatic stress were also found.

Thus, generating actions for the promotion and protection of mental health is more necessary than ever to take care of health workers as people and their ability to attend and respond to the daily demands in health institutions, improving their adaptation to stress and decision-making based on problem solving rather than emotion and uncertainty. This can positively impact the healthcare process and the institutional capacity to maintain a prolonged care response, keeping all possible staff available in the best conditions.5

For this reason, it is considered necessary to generate recommendations for the promotion and protection of mental health care for health workers and teams working on the front line during and after the COVID-19 health emergency.

MethodsTwo methods were used: a structured literature search and an expert consensus.

A rapid literature search was carried out with the key terms “mental health”, “COVID-19” and “coronavirus” in English and Spanish in the PubMed database and in Google Scholar, which was complemented with a snowball search of the references found within the structured search results. All documents that provided information on the impact on the mental health of health workers during COVID-19 or in situations of humanitarian crisis, as well as documents that offered information or guidelines for preventive care or interventions in mental health during crisis situations, were included.

All documents related to the treatment of pre-existing mental illness during COVID-19, research protocols, and those that could not be retrieved in full text were excluded.

The search for information as of 3 March had yielded 12 publications: 1 rapid systematic review, 2 cross-sectional studies, 2 opinion articles and 7 publications by the WHO, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Mental Health Europe, Harvard Medical School and the Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress.

An update of the search was carried out on 11 April, which yielded 88 additional publications to those found in the first search, related to cross-sectional studies, expert opinions and the development of technological tools and interventions for emotional and psychological support for workers.

A consensus was made for the review and feedback of the recommendations developed from the literature. The consultation was electronic and had the participation of 13 experts in the areas of clinical psychology, psychiatry, nursing, occupational health and safety, organisational psychology and anthropology, and specialists in family and internal medicine.

These recommendations were endorsed by the Sociedad Colombiana de Psiquiatría [Colombian Society of Psychiatry] and the Colegio Colombiano de Psicólogos [Colombian Association of Psychologists].

All the recommendations in this document have a level of evidence 5b15 according to the international guidelines of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) and a strength level of B or weak.16

ResultsRecommendationsRecommendations for the self-care of health workers during COVID-19It is recommended that workers develop individual activities that facilitate adaptation to new work demands, emotional management, strengthening of their social and family environment and the use of the support, services or materials provided by the institutions for caring for their mental health (weak recommendation in favour).

As strategies for adapting to new demands, it is recommended to reorganise the daily routine incorporating leisure activities that generate well-being, joy or happiness, and rest periods understood as total disconnection from the stressful environment for at least 10 min (weak recommendation in favour).

It is recommended to maintain eating and sleeping habits as much as possible, since they may tend to deteriorate or be ignored in situations of agitation and stress (weak recommendation in favour).

The inclusion of rest period activities can improve cognitive functions of attention and concentration and decision-making in the care process.

The inclusion of leisure activities can increase motivation and promote a regulated mood during the workday.

Stress, depressive or anxious symptoms, fear and uncertainty can be experienced in response to the pressure and responsibility felt in the workplace, when caring for a symptomatic person or being in the same physical space, given the possibility of getting infected and spreading the virus to family, friends, colleagues and patients, for which it is recommended to carry out techniques for emotional management on a daily basis (weak recommendation in favour).

As strategies for emotional management, it is recommended to do daily breathing and focused attention (mindfulness) exercises before starting and at the end of care activities (weak recommendation in favour).

The atypical situations that the COVID-19 pandemic entails, such as providing healthcare with limited resources, the continuous deaths of a high percentage of patients, and demanding work hours can generate frustration, a sense of being overwhelmed and anger that affect decision-making and the well-being of the worker, so active participation in coping groups or in the development of emotional regulation techniques is recommended (weak recommendation in favour).

It is recommended to avoid the circulation of unscientific information about COVID-19, overexposure to information about COVID-19 outside the workplace and consulting information about COVID-19 several times a day for entertainment purposes, since this can increase the anxiety and uncertainty of health workers and health teams (weak recommendation in favour).

To strengthen the social area, it is recommended to establish fixed spaces during the week for virtual social contact via video calls or other virtual channels that allow verbal and non-verbal communication with relevant and important people (weak recommendation in favour).

Continuous virtual contact can increase motivation, decrease the perception of loneliness, avoid isolation in workers and build close support networks.

Family contact is also considered a protective factor and a source of well-being in times of crisis, which is why it is recommended to maintain close contact through weekly video calls or other virtual channels that allow verbal and non-verbal communication (weak recommendation in favour).

Faced with situations that are overwhelming or that make it difficult for workers to carry out their daily care activities, it is recommended to identify and use the channels and strategies provided by the health institution for psychotherapeutic support by specialised personnel (psychologists and psychiatrists). In the absence of these, it is recommended to consult with the health service provider or other platforms available in the country for emotional and psychological support (weak recommendation in favour).

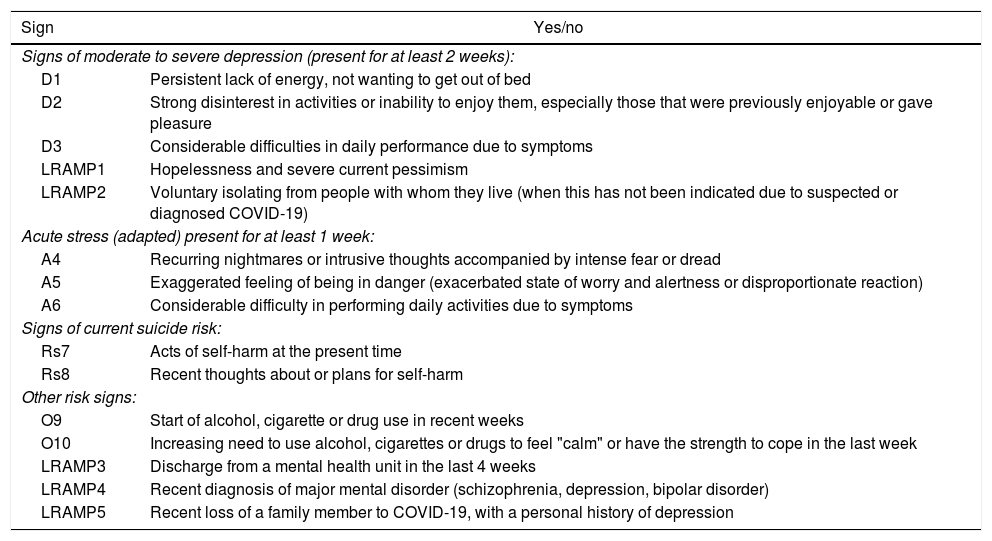

Some of the situations that may motivate consulting a specialised professional are described in Table 1.

Mental health warning signs for depression, acute stress, suicide risk and others.

| Sign | Yes/no |

|---|---|

| Signs of moderate to severe depression (present for at least 2 weeks): | |

| D1 | Persistent lack of energy, not wanting to get out of bed |

| D2 | Strong disinterest in activities or inability to enjoy them, especially those that were previously enjoyable or gave pleasure |

| D3 | Considerable difficulties in daily performance due to symptoms |

| LRAMP1 | Hopelessness and severe current pessimism |

| LRAMP2 | Voluntary isolating from people with whom they live (when this has not been indicated due to suspected or diagnosed COVID-19) |

| Acute stress (adapted) present for at least 1 week: | |

| A4 | Recurring nightmares or intrusive thoughts accompanied by intense fear or dread |

| A5 | Exaggerated feeling of being in danger (exacerbated state of worry and alertness or disproportionate reaction) |

| A6 | Considerable difficulty in performing daily activities due to symptoms |

| Signs of current suicide risk: | |

| Rs7 | Acts of self-harm at the present time |

| Rs8 | Recent thoughts about or plans for self-harm |

| Other risk signs: | |

| O9 | Start of alcohol, cigarette or drug use in recent weeks |

| O10 | Increasing need to use alcohol, cigarettes or drugs to feel "calm" or have the strength to cope in the last week |

| LRAMP3 | Discharge from a mental health unit in the last 4 weeks |

| LRAMP4 | Recent diagnosis of major mental disorder (schizophrenia, depression, bipolar disorder) |

| LRAMP5 | Recent loss of a family member to COVID-19, with a personal history of depression |

Adapted from: mhGAP Humanitarian Intervention Guide (mhGAP-HIG). WHO. 2015. https://iris.paho.org/bitstream/handle/10665.2/28418/9789275319017_spa.pdf?sequence=6&isAllowed=y, and Linehan MM. Linehan Risk Assessment & Management Protocol (LRAMP). University of Washington Risk Assessment Action Protocol: UWRAMP, University of WA; 2009.

Due to their close contact with patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, healthcare workers may suffer discrimination and social rejection by the general population. For these cases, it is recommended to strengthen coping through strategies that increase resilience capacity and assertive communication (weak recommendation in favour).

Recommendations for community care among health teamsFor care among members of health teams, it is recommended to have strategies in place for strengthening relationships and social cohesion, as well as for detecting and managing mental health risks (weak recommendation in favour).

To strengthen relationships and social cohesion, it is recommended to establish periodic virtual spaces for dialogue in contexts other than the health situation due to COVID-19 (weak recommendation in favour).

Closer relationships can facilitate the search for and obtaining of support among team members, which would facilitate the timely identification of workers who may require specialised psychological support.

It can also help with coping with situations of social discrimination and reduce the isolation of workers who live alone or are far from their families.

Clear and timely communication favours the development of activities in health institutions. For this reason, it is recommended to generate specific channels to ensure the diffusion of and access to relevant information on COVID-19 (weak recommendation in favour).

The collective experience of physical distancing due to demanding hours and temporary accommodation outside the home can generate a sense of isolation in health workers or lead to inappropriate behaviours of close social contact outside the work environment, for which it is recommended to open virtual spaces that can be oriented to emotional management, as a health team, of the experiences, emotions and difficulties experienced in the service (weak recommendation in favour).

Community management of emotions can improve emotional regulation in working hours and performance, and detect common situations that can be intervened or improved within care activities.

It is recommended that virtual spaces for emotion management be frequent, validating, non-punitive and accompanied by a trained facilitator (weak recommendation in favour).

Health team leaders recommend that environmental conditions (permits, specific times) for the development of community care strategies among health teams be promoted (weak recommendation in favour).

It is recommended that the leader constantly monitors compliance with these strategies within health teams (weak recommendation in favour).

Close support from leaders can facilitate the conditions, motivation and participation for the optimal development of community care strategies.

Recognition of the current situation by the health team and of how they are coping with it can generate strategies that mitigate or reduce attrition in personnel and their rotation.

For stress management across teams, it is proposed to rotate workers from higher stress to lower stress roles, and put inexperienced workers together with their more experienced colleagues (weak recommendation in favour).

The “buddy” system helps provide support, manage stress, and enforce quality and safety standards.

Team leaders also face stressors similar to those of their staff and a corresponding pressure added to the level of responsibility of their position. For this reason, it is recommended to develop strategies and adapt the recommendations for their mental health self-care (weak recommendation in favour).

Resilience in health workers can be very high, but it is recommended to carry out a systematic and periodic evaluation of mental health warning signs for timely intervention actions (weak recommendation in favour).

Recommendations for the screening of mental health warning signsIt is recommended to focus the screening on mental health alarm signs for depression, anxiety, acute stress, suicidal risk and substance use (Table 1) (weak recommendation in favour).

It is recommended to constantly screen and have specific support instruments for workers who have some type of disability or a history of mental illness or psychological disorder (weak recommendation in favour).

It is recommended that the pathways consistent with the screening results incorporate support and intervention channels within the health institution, as well as referral to the health worker's service provider (weak recommendation in favour).

For the design of care pathways and support strategies in health institutions, close support of the psychosocial teams available in each centre is recommended (weak recommendation in favour).

Given the shortage of health talent trained to be on the front line of care for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19, it is recommended to prioritise the psychological and psychiatric support they may require (weak recommendation in favour).

Recommendations for healthcare institutionsBecause the health situation caused by COVID-19 is considered long-term, it is recommended to plan medium and long-term strategies for promoting and treating the mental health of health workers (weak recommendation in favour).

In planning, it is recommended to identify and prioritise services or groups with high risk, which include emergency, intensive care and general hospitalisation services, to which preventive strategies in mental health can be directed (weak recommendation in favour).

It is recommended to include in the strategies the training of key workers within the services in basic emotional management techniques such as psychological first aid (weak recommendation in favour).

For workers who are self-isolating due to COVID-19 infection or are unable to work for other reasons, it is proposed to establish concrete actions of support and emotional accompaniment (weak recommendation in favour).

Having to self-isolate can exacerbate health workers' concerns about causing extra work for colleagues or about the lack of staff in their workplace. It can also increase feelings of isolation and frustration at being separated from your team or, conversely, lead to feelings of relief and guilt.

After the end of the health emergency, it is recommended to maintain a systematic process of evaluation of alarm signs within the work teams for a minimum of six months, as well as to keep the care and support channels active for that time (weak recommendation in favour).

DiscussionCaring for health workers in times of crisis is essential, therefore, all the measures introduced to guarantee their personal protective equipment, compliance with the protocols for the care of patients with suspected or diagnosed infection, and the retention of staff within health institutions are some of the main challenges in the pandemic. However, the mental health component is another one that requires special attention and concrete actions to be taken, since these generate another type of “protection” focused on ensuring the optimal disposition, guarantee of availability and best performance of health workers and their quality of life.

Some efforts in this area have been made, for example, in China, where social support interventions to help tackle COVID-19 have been carried out to improve the quality of sleep for medical personnel on the front line of care17 or to facilitate access to materials and mental health care.18 The staff themselves valued these as important resources for alleviating acute mental health disorders and improving their perceptions of physical health.

These actions become more important when analysing their impact in three areas: the health system itself, by maintaining its response capacity in the pandemic making use of all possible human resources; the care process itself, which involves the health institution and the patients and can be optimised and improved by a team with adequate coping and decision-making skills; and finally, the people themselves who make up this “human talent”, which shows the need to work in an organised manner and with joint responsibility between health institutions and health workers themselves.

ConclusionsThe activities for the promotion and protection of mental health to face the health emergency generated by the COVID-19 pandemic can range from individual worker self-care actions and community care actions generated by members of the health teams, to those made by health institutions through the provision of organisational support channels during the emergency and after it, offering comprehensive, community, co-responsible and maintained care.

The well-being derived from the active, individual, community and institutional care of health workers' mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic can also contribute in the long term to their quality of life and reduce the probability of suicides, depression disorders, anxiety disorders and behaviour patterns such as substance abuse that significantly affect society.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Cantor-Cruz F, McDouall-Lombana J, Parra A, Martin-Benito L, Quesada NP, González-Giraldo C, et al. Cuidado de la salud mental del personal de salud durante COVID-19: recomendaciones basadas en evidencia y consenso de expertos. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2021;50:225–231.