Colombia is one of the countries with the highest levels of internal displacement resulting from armed conflict. This population has greater chances of experiencing a mental health disorder, especially in territories historically affected by armed conflict. Our objective was to compare the levels of possible mental health disorder in people experiencing internal displacement in Meta, Colombia, a department historically affected by armed conflict, compared to the internally displaced population in the National Mental Health Survey of 2015.

MethodsAnalysis of data collected in the National Mental Health Survey (ENSM) of 2015, study with representative data at national level and the Conflict, Peace and Health survey (CONPAS) of 2014, representative study of the degree of impact of the conflict on the municipality, conducted in the department of Meta, Colombia. To measure possible mental health disorder, the Self-Report Questionnaire-25 (SRQ-25) was used. Internal displacement is self-reported by people surveyed in both studies. An exploratory analysis is used to measure possible mental health disorders in the displaced population in the ENSM 2015 and CONPAS 2014.

Results1089 adults were surveyed in CONPAS 2014 and 10,870 adults were surveyed in the ENSM 2015. 42.9% (468) and 8.7% (943) of people reported being internally displaced in CONPAS 2014 and ENSM 2015, respectively. In both studies, internally displaced populations have greater chances of experiencing any mental health disorder compared to non-displaced populations. For CONPAS 2014, 21.8% (95%CI, 18.1−25.8) of this population had a possible mental health disorder (SRQ+) compared to 14.0% (95%CI, 11.8−16.3) in the ENSM 2015. Compared with the ENSM 2015, at the regional level (CONPAS 2014), displaced people had a greater chance of presenting depression by 12.4% (95%CI, 9.5−15.7) compared to 5.7% (95%CI, 4.3−7.4) in the ENSM 2015, anxiety in 21.4% (95%CI, 17.7−25.3) compared to 16.5% (95%CI, 14.2−19.1) in the ENSM 2015, and psychosomatic disorders in 52.4% (95%CI, 47.5−56.7) in CONPAS 2014 compared to 42.2% (95%CI, 39.0−45.4) in the ENSM 2015. At the national level (ENSM 2015), displaced people had greater possibilities of presenting, compared to the regional level, suicidal ideation in 11.9% (95%CI, 9.3–14.1) compared to 7.3% (95%CI, 5.0−10.0) in CONPAS 2014 and bipolar disorder in 56.5% (95%CI, 53.2−59.7) compared to 39.3% (95%CI, 34.8−43.9) in CONPAS 2014.

ConclusionsThe greater possibilities of displaced populations at the regional level of experiencing a mental health disorder, compared to this same population at the national level, may represent and indicate greater needs in mental health care services in territories affected by conflict. Therefore, and given the need to facilitate access to health services in mental health for populations especially affected by armed conflict, there is a need to design health care policies that facilitate the recovery of populations affected by war and, simultaneously, that reduce inequities and promote the fulfilment of one of the most important and, at the same time, least prioritised health objectives in international development: mental health.

Colombia es uno de los países del mundo con mayor volumen de desplazamiento interno a causa de un conflicto armado interno. Esta población tiene mayores posibilidades de sufrir un trastorno de salud mental, sobre todo en territorios afectados históricamente por el conflicto. El objetivo es comparar la prevalencia de posibles trastornos de la salud mental entre las personas en condición de desplazamiento en Meta, departamento de Colombia históricamente afectado por el conflicto armado, frente a población desplazada en todo el país según la Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental (ENSM) de 2015.

MétodosAnálisis de datos recolectados en la ENSM 2015, estudio a escala nacional, y la encuesta Conflicto, Salud y Paz (CONPAS) de 2014, estudio representativo del grado de afectación por el conflicto en el municipio, realizado en el departamento del Meta. Para medir un posible trastorno de la salud mental, se utiliza el Self Report Questionnaire-25 (SRQ-25). La condición de desplazamiento fue declarada por los encuestados en ambos estudios. Se hizo un análisis descriptivo sobre el posible trastorno de la salud mental en la población desplazada de la ENSM 2015 y la CONPAS 2014.

ResultadosSe encuestó a 1.089 adultos en la CONPAS 2014 y 10.870 adultos en la ENSM 2015. El 42,9% (468) y el 8,7% (943) de las personas reportaron estar en condición de desplazamiento en la CONPAS 2014 y la ENSM 2015 respectivamente. En ambos estudios, la población desplazada tiene mayores posibilidades de sufrir cualquier trastorno de la salud mental que la población no desplazada. En la CONPAS 2014, el 21,8% (intervalo de confianza del 95% [IC95%], 18,1–25,8) de esta población tenía un posible trastorno de la salud mental (SRQ+) frente al 14,0% (IC95%, 11,8–16,3) en la ENSM 2015. Los encuestados en condición de desplazamiento de la CONPAS 2014 tuvieron mayor probabilidad que los de la ENSM 2015 en depresión —el 12,4% (IC95%, 9,5–15,7) frente al 5,7% (IC95%, 4,3–7,4)—, ansiedad —el 21,4% (IC95%, 17,7–25,3) frente al 16,5% (IC95%, 14,2–19,1)— y trastornos psicosomáticos —el 52,4% (IC95%, 47,5–56,7) frente al 42,2% (IC95%, 39,0–45,4)—. Los desplazados de la ENSM 2015 tenían mayor probabilidad de ideación suicida, el 11,9% (IC95%, 9,3–14,1) frente al 7,3% (IC95%, 5,0–10,0) en la CONPAS 2014, y trastorno bipolar, el 56,5% (IC95%, 53,2–59,7) frente al 39,3% (IC95%, 34,8–43,9).

ConclusionesLa mayor probabilidad de trastornos de la salud mental (SRQ+) de la población regional en condición de desplazamiento frente a toda la población nacional en esa condición puede representar una mayor necesidad de servicios de atención en salud mental en los territorios afectados por el conflicto. Así pues, y dada la necesidad de facilitar el acceso y la atención médica en salud mental a poblaciones especialmente afectadas por el conflicto armado, es importante el diseño de políticas de atención en salud que faciliten la recuperación de poblaciones afectadas por la guerra y, simultáneamente, reducir inequidades y promover el cumplimiento de uno de los objetivos en salud más importantes y, a la vez, usualmente menos priorizados en el desarrollo internacional: la salud mental.

Armed conflicts have serious repercussions on the mental health of the people involved, whether they are victims, illegal armed groups, the army or the civilian population in general.1 Events of this type increase the prevalence of mental disorders, mainly as a result of experiencing traumatic events, the fear of such events being repeated and the difficulty accessing emotional support networks.2 The lack of health services, especially in mental health, during times of conflict makes care provision difficult and leads to situations like in Colombia where, because the armed confrontation has been ongoing, the negative effects of poor quality mental health persist.3

In the long term, such a situation increases the global burden of disease (GBD), reduces both the productive potential of those affected and their ability to make their individual contributions to society, and prevents them from being able to fully participate and exercise their rights, all of which can lead these individuals to situations of poverty and social exclusion.4 This scenario promotes inequality and results in these societies having worse human development indicators, greater institutional instability, lower growth rates and fewer opportunities for long-term economic and social development.5

The decades of armed conflict in Colombia have resulted in different types of mental health disorder in the population.6–8 Populations which are victims of, or exposed to, such conflicts are more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation.9 The lack of access to healthcare services makes treatment and care difficult and puts these people at greater risk in the long term.10 Moreover, other social or cultural barriers, such as distrust in the healthcare system or social prejudices towards certain communities, can prevent people from taking full advantage and making full use of the available medical services in some regions.11 These repercussions are more evident in the places that have suffered most from the war. One such case is Meta, a department in the east of the country that was one of the strategic sites for paramilitary groups and the FARC-EP, formerly a guerrilla organisation and now a political party after the signing of the 2016 peace accords and their subsequent demobilisation in 2017.

One of the population groups most at risk of suffering mental disorders due to armed conflict is displaced persons.12–14 This population is permanently exposed to situations and contexts in which their basic rights are violated and they may at times be stigmatised due to their condition, a stress factor which then imposes an additional burden on their psychological well-being.6 In addition, they tend to have worse access to healthcare services and, having been expelled from their places of origin, have suffered forced separation from essential primary support networks, such as friends and family. This is an added restriction that hinders recovery from stressful events and helps create a vicious circle which further violates their rights.15 Such a scenario can be more serious in regions or territories where there has been no ceasefire, or where there are few security guarantees or little State institutional presence, meaning the displaced population is constantly living in a state of stress.16

In Colombia, as a public policy intervention strategy, the government introduced the Programa de Atención Psicosocial y Salud Integral a las Víctimas (PAPSIVI) [Psychosocial Care and Comprehensive Health Programme for Victims]. The aim of the programme was to address the medical and psychosocial disorders deriving from victimising events people have suffered as a result of the armed conflict.17 However, in recent years, the programme has experienced difficulties in some regions due to problems with coverage, interrupted care in some areas and difficulties in adequately measuring and diagnosing the prevalence of mental health disorders in certain regions and providing care to certain population groups, including displaced persons.18

Because of this, in areas where the conflict has had a greater impact and access to mental healthcare programmes and services is challenging, displaced persons may be more likely to suffer from mental health disorders than in other parts of the country. The 2015 Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental (ENSM) [National Mental Health Survey] showed a significant prevalence of mental health disorders in populations that were victims of displacement.19 However, these national studies may obscure the mental health scenario in regions affected by conflict, where victims of displacement may be subject to other risk factors or other direct effects of the conflict. It is therefore important to have comparative studies of this type between the regions and the country as a whole to provide an exploratory analysis of the differences in the mental health of the displaced populations in each area, and so identify whether or not there are major differences in mental health from one area of the country to another.

This study compares the prevalence of possible mental health disorders in 2014 in displaced persons in Meta, a department of Colombia historically affected by armed conflict, to that of the displaced population throughout the country in 2015.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study from a secondary source based on data from the 2015 ENSM20 and the 2014 Encuesta Conflicto, Paz y Salud (CONPAS) [Conflict, Peace and Health Survey]. The 2015 ENSM was a nationally representative survey stratified by gender, age and region, from a sub-sample of the Master Sample of Colombian Ministry of Health and Social Protection population studies. For this research, information from respondents aged 18 years or over (n=10,870) was exclusively used.

For this study, information from the CONPAS survey, completed by 1309 households in the department of Meta, was also used. Respondents were selected using a probabilistic design stratified at the level of incidence of the conflict in the municipality of residence and urban and rural areas. Using a multistage sampling method, we selected populated centres or villages and, in the interior of the country, map squares. In the last two stages, dwellings and one household for each of these were selected through simple random sampling without replacement. For this research, the answers given by the head of the household were used, who was asked about the socioeconomic conditions of the household, opportunities to access healthcare and quality of care received, and general questions about their state of health.

The CONPAS survey was conducted in 2018, but included retrospective questions from 2014 applied to the same population on the characteristics already described. In order to guarantee comparability between the CONPAS and the ENSM, only information from the CONPAS for the year 2014 was used and, in particular, from the people who were over 18 years of age that year and were living in Meta (n=1089). This strategy improved the comparability of both studies by specifically focusing on of-age populations and on similar time periods.

In both surveys, the Self-Report Questionnaire-25 (SRQ-25)21 was used to measure possible mental health disorders. This is a questionnaire developed by the World Health Organization that asks the respondent if they have had a series of characteristic symptoms of various mental disorders in the last 30 days. For this study, the first 20 questions of the SRQ were used. A person has a tendency towards a mental disorder (SRQ+) if they answer affirmatively to at least 14 of the first 20 questions of the questionnaire (70%). Through the questions in the SRQ and using the criteria recommended in the literature,21 the possible presence of the following disorders was measured in the population of displaced victims: depression, anxiety, psychosis, psychosomatic disorders, bipolar disorder and suicidal ideation. This instrument has been previously validated in Colombia22 for its application in national mental health surveys19 and to the displaced population.23

In both studies, the condition of being displaced was stated by the respondent and was measured identically. Both in the ENSM and in the CONPAS, a person was considered to be a victim of displacement if they reported having changed their residence or address as a result of threats or violence arising from armed conflict.

For this research, a review of academic databases was conducted using a search equation consisting of a combination of the most important keywords and operators. The equation was repeated in databases such as MEDLINE (new version), Scopus, WoS Core Collection, CINAHL Plus, Ebsco and Cochrane. In view of the need for more specific information, specialised equations were created for MEDLINE (new version), Scopus and Cochrane. In addition, the search was further restricted with search fields and limits, such as publication dates. Subsequently, repeated articles or those going beyond the scope of the study were ruled out. This search was the first step in establishing research priorities and facilitated discussion of relevant results from other publications.

The rates of possible mental health disorders were estimated by calculating the proportion (as a percentage) with its respective 95% confidence interval (95% CI) using the Taylor series approximation method.24 The CONPAS survey has pre-assigned weights and uses as a stratification variable the degree to which the conflict has affected the municipality and the area of residence (rural, urban). All calculations were performed using Stata 15.1/IC software.

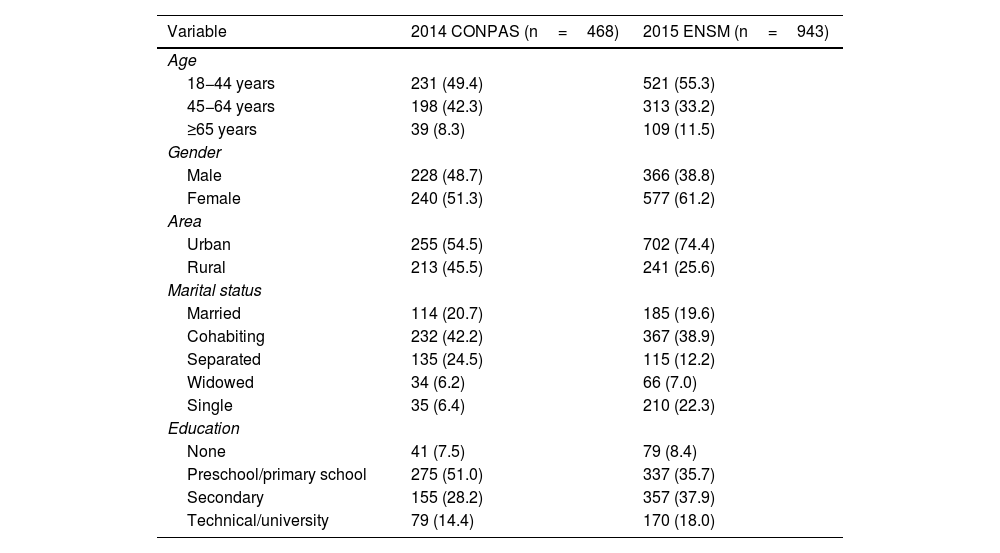

ResultsPopulation characteristicsThe 2014 CONPAS surveyed 1089 people over the age of 18, of whom 468 (42.9%) reported being displaced. In the 2015 ENSM, 10,870 adults were surveyed, and 934 (8.7%) stated that they were displaced. Table 1 shows descriptive statistics on the main characteristics of these two populations.

Characteristics of the displaced population in the 2014 CONPAS and the 2015 ENSM.

| Variable | 2014 CONPAS (n=468) | 2015 ENSM (n=943) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18−44 years | 231 (49.4) | 521 (55.3) |

| 45−64 years | 198 (42.3) | 313 (33.2) |

| ≥65 years | 39 (8.3) | 109 (11.5) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 228 (48.7) | 366 (38.8) |

| Female | 240 (51.3) | 577 (61.2) |

| Area | ||

| Urban | 255 (54.5) | 702 (74.4) |

| Rural | 213 (45.5) | 241 (25.6) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 114 (20.7) | 185 (19.6) |

| Cohabiting | 232 (42.2) | 367 (38.9) |

| Separated | 135 (24.5) | 115 (12.2) |

| Widowed | 34 (6.2) | 66 (7.0) |

| Single | 35 (6.4) | 210 (22.3) |

| Education | ||

| None | 41 (7.5) | 79 (8.4) |

| Preschool/primary school | 275 (51.0) | 337 (35.7) |

| Secondary | 155 (28.2) | 357 (37.9) |

| Technical/university | 79 (14.4) | 170 (18.0) |

Values are expressed in terms of n (%).

Table 1 reveals that the highest proportion of displaced people was in the 18−44 age group, both in the 2014 CONPAS (49.4%) and in the 2015 ENSM (55.3%). There were more displaced women than men (51.3% and 61.2%). In the 2014 CONPAS, the largest proportion of displaced people lived in rural areas (45.5%), while in the 2015 ENSM, the displaced population in rural areas was much lower (25.6%). In both surveys, cohabitation predominated (42.2% and 38.9%), followed by people who were separated in the 2014 CONPAS (24.5%) and single people in the 2015 ENSM (22.3%). Lastly, in the 2014 CONPAS, most people's level of education was preschool/primary (51.0%) or secondary (28.2%), while in the 2015 ENSM, the largest proportion of respondents (37.9%) had secondary education or technical or further education (18.0%).

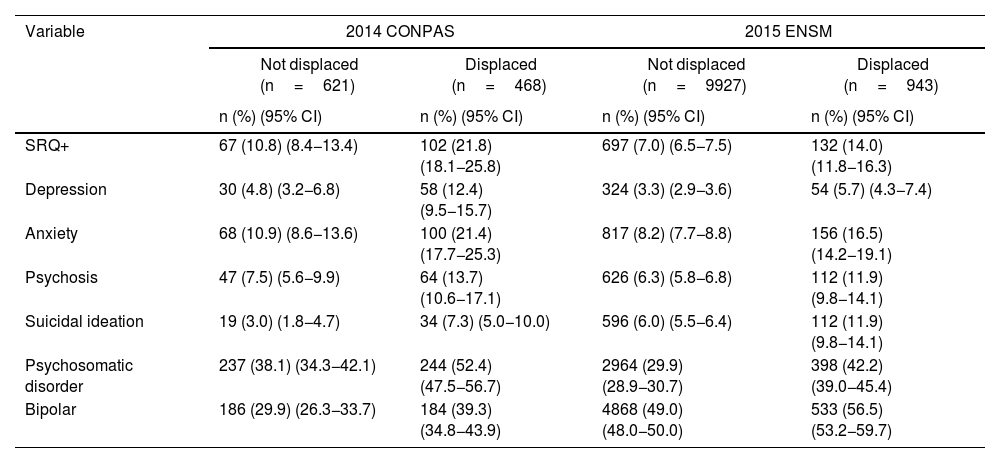

Possible presence of mental health disordersTable 2 shows the presence of a possible mental health disorder in the displaced population according to the 2014 CONPAS and the 2015 ENSM, estimated using the SRQ. The results are presented for both the displaced and non-displaced population in order to show whether or not there are significant differences between these two groups in both surveys.

Mental health disorders in the displaced and non-displaced population from the 2014 CONPAS and 2015 ENSM.

| Variable | 2014 CONPAS | 2015 ENSM | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not displaced (n=621) | Displaced (n=468) | Not displaced (n=9927) | Displaced (n=943) | |

| n (%) (95% CI) | n (%) (95% CI) | n (%) (95% CI) | n (%) (95% CI) | |

| SRQ+ | 67 (10.8) (8.4−13.4) | 102 (21.8) (18.1−25.8) | 697 (7.0) (6.5−7.5) | 132 (14.0) (11.8−16.3) |

| Depression | 30 (4.8) (3.2−6.8) | 58 (12.4) (9.5−15.7) | 324 (3.3) (2.9−3.6) | 54 (5.7) (4.3−7.4) |

| Anxiety | 68 (10.9) (8.6−13.6) | 100 (21.4) (17.7−25.3) | 817 (8.2) (7.7−8.8) | 156 (16.5) (14.2−19.1) |

| Psychosis | 47 (7.5) (5.6−9.9) | 64 (13.7) (10.6−17.1) | 626 (6.3) (5.8−6.8) | 112 (11.9) (9.8−14.1) |

| Suicidal ideation | 19 (3.0) (1.8−4.7) | 34 (7.3) (5.0−10.0) | 596 (6.0) (5.5−6.4) | 112 (11.9) (9.8−14.1) |

| Psychosomatic disorder | 237 (38.1) (34.3−42.1) | 244 (52.4) (47.5−56.7) | 2964 (29.9) (28.9−30.7) | 398 (42.2) (39.0−45.4) |

| Bipolar | 186 (29.9) (26.3−33.7) | 184 (39.3) (34.8−43.9) | 4868 (49.0) (48.0−50.0) | 533 (56.5) (53.2−59.7) |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval.

The proportion of displaced persons with a possible mental health disorder (SRQ+) is higher in the 2014 CONPAS (21.8%) than in the 2015 ENSM (14.0%). In addition, a larger proportion of displaced persons in the 2014 CONPAS had possible depression, anxiety, psychosis and psychosomatic disorders; 12.4% (95% CI, 9.5−15.7) in the 2014 CONPAS had possible depression compared to 5.7% (95% CI, 4.3−7.4) in the 2015 ENSM. Similarly, 21.4% (95% CI, 17.7−25.3) had possible anxiety, compared to 16.5% (95% CI, 14.2−19.1) in the 2015 ENSM, and 52.4% (95% CI, 47.5−56.7) possible psychosomatic disorders, compared to 42.2% (95% CI, 39.0−45.4) in the 2015 ENSM.

Comparing national to regional figures, displaced people have a greater likelihood of suicidal ideation and possible bipolar disorder. In the 2015 ENSM, 11.9% (95% CI, 9.3–14.1) had possible suicidal ideation, compared to 7.3% (95% CI, 5.0−10.0) in the 2014 CONPAS. In turn, in the 2015 ENSM, 56.5% (95% CI, 53.2−59.7) had a possible bipolar disorder compared to 39.3% (95% CI, 34.8−43.9) in the 2014 CONPAS.

In both surveys there was a higher proportion of displaced people with a possible mental disorder (SRQ+) compared to the non-displaced. Similarly, in both surveys the proportion of displaced persons with possible depression, anxiety, psychosis, psychosomatic disorders, suicidal ideation and bipolarity was higher than in the non-displaced population.

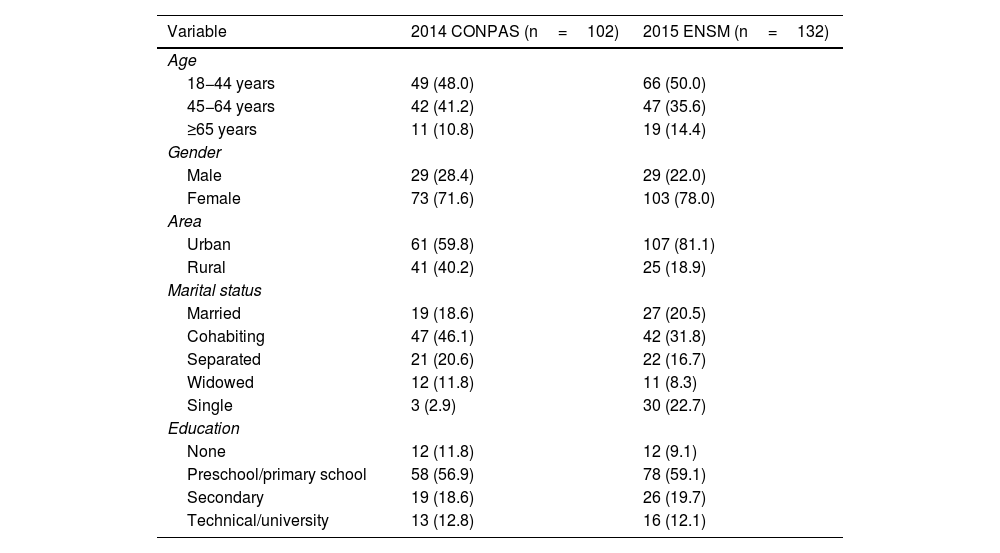

Characteristics of the population with SRQ+Table 3 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the displaced population from both surveys with possible mental health disorders (SRQ+). The 18−44 age group was more likely to suffer a mental health disorder (SRQ+) (48.0% and 50.0%, respectively) compared to older people. In both surveys, most of the cases of SRQ+ were females (71.6% in the 2014 CONPAS and 78.0% in the 2015 ENSM). The highest proportion of SRQ+was found in urban areas (59.8% and 81.8%). The largest proportions of SRQ+displaced populations were cohabiting (46.1% and 31.8%) and had preschool or primary school education (56.9% and 59.1%).

Characteristics of the displaced population with SRQ+in the 2014 CONPAS and the 2015 ENSM.

| Variable | 2014 CONPAS (n=102) | 2015 ENSM (n=132) |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| 18−44 years | 49 (48.0) | 66 (50.0) |

| 45−64 years | 42 (41.2) | 47 (35.6) |

| ≥65 years | 11 (10.8) | 19 (14.4) |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 29 (28.4) | 29 (22.0) |

| Female | 73 (71.6) | 103 (78.0) |

| Area | ||

| Urban | 61 (59.8) | 107 (81.1) |

| Rural | 41 (40.2) | 25 (18.9) |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 19 (18.6) | 27 (20.5) |

| Cohabiting | 47 (46.1) | 42 (31.8) |

| Separated | 21 (20.6) | 22 (16.7) |

| Widowed | 12 (11.8) | 11 (8.3) |

| Single | 3 (2.9) | 30 (22.7) |

| Education | ||

| None | 12 (11.8) | 12 (9.1) |

| Preschool/primary school | 58 (56.9) | 78 (59.1) |

| Secondary | 19 (18.6) | 26 (19.7) |

| Technical/university | 13 (12.8) | 16 (12.1) |

Values are expressed in terms of n (%).

This study compared the incidences of possible mental health disorders in the displaced population in the department of Meta and throughout Colombia. To do this, the information from the 2015 ENSM and the results of the CONPAS survey were analysed. In both studies, there were more cases of possible mental health disorder (SRQ+) among women, residents of urban areas, cohabiting couples and people who had not progressed beyond primary education. However, our study reveals a higher proportion of displaced persons with an SRQ+in the CONPAS compared to the 2015 ENSM. Depression, anxiety and psychosomatic disorders were more likely in the displaced population of Meta. In contrast, psychosis and suicidal ideation were more likely in the ENSM than in the regional survey.

LimitationsThe information from 2014 was collected retrospectively when the survey was carried out in 2018. This means there may be some biases in the reporting due to problems with information recall. Due to the strong stigma attached to the subject of mental health for some people, it is possible that some disorders have been under-reported. As the SRQ is not a diagnostic tool, the actual proportion of people with a mental disorder may vary in both surveys.

InterpretationRelationship between displacement and possible mental health disorderThe results from Meta confirm the national trend suggested by the 2015 ENSM. In both surveys, a positive correlation was identified between having suffered displacement and the tendency to suffer from any type of mental disorder. Our results therefore show a connection between traumatic life events and exposure to displacement, a trend reported previously in Colombia.25

The relationship between displacement and possible mental disorder is consistent with other Colombian and international studies. For Campo-Arias and Herazo,6 the prevalence of mental disorders in the displaced population in Colombia is associated with different social inequalities suffered by this population. These include fewer opportunities, higher levels of discrimination and the widespread stigma suffered by the displaced population. Kuwert et al.26 quantified the impact of long-term displacement in war zones in Europe. Here, displacement significantly leads to anxiety disorders, depressive symptoms and general dissatisfaction.

It is interesting to see that in the 2014 CONPAS, anxiety was more likely than depression in the displaced population. In individuals recently displaced after the civil war in Sri Lanka, Husain et al.27 reported a greater likelihood of depression (odds ratio [OR]=4.55; 95% CI, 2.47–8.39) than anxiety (OR=2.91; 95% CI, 1.89–4.48). Our conclusions show less likelihood of possible depression in the CONPAS than in other studies.28,29 These differences may be due to the difference in the amount of time between the event that caused the displacement and the declaration of symptoms. Despite these differences, our results are in line with other research in which anxiety disorders, sleep problems and psychosomatic disorders are the most common conditions among the displaced population.9,30

The appearance of suicidal ideations and tendencies in the CONPAS results is striking. Suicide is generally more related to depression than to anxiety,19 and in this study anxiety was much more common than depression. Although exposure to traumatic events can trigger depressive episodes, some people tend to develop personal strategies to face up to and manage their emotions in conflict situations, which can reduce the chances of a depressive disorder.25 However, continuous exposure to traumatic events and the permanent feeling of insecurity that characterise this population is usually reflected in a high incidence of anxiety and psychosomatic disorders.31 Previous studies have linked the greater suicidal tendencies in the displaced population with greater exposure to traumatic events such as sexual violence, death of friends or relatives, or domestic violence.32 In view of the particular vulnerability of the displaced population, therefore, recognising and addressing the existence of suicidal ideas, plans and/or acts needs to be a priority in any preventive mental health plan aimed at this population. Understanding how conflicts affect people, their interpersonal relationships and the psychological well-being of the displaced population in general is key to designing comprehensive health policies for these communities.33

Comparison of possible mental health disorders between the region and nationwideThe ENSM reports 943 adults with displaced status (8.7%),19 a figure much lower than the displacement rates reported in the 2014 CONPAS (468; 42.9%). Such differences may reflect the considerable exposure to conflict in Meta compared to the national average,34 as well as the historical trend of higher displacement rates in rural areas compared to urban populations in Colombia.35,36

Interestingly, in the displaced population, the likelihood of a mental health disorder was higher in the CONPAS (21.8%; 95% CI, 18.1−25.8) than in the 2015 ENSM (14.0% 95% CI, 11.8−16.3). Depression in particular was more common in the CONPAS (12.4%; 95% CI, 9.5−15.7) than in the ENSM (5.7%; 95% CI, 4.3−7.4). Anxiety was also more common in the CONPAS, at 21.4% (95% CI, 17.7−25.3) compared to 16.5% (95% CI, 14.2−19.1). These differences may reflect greater suffering as a result of the armed conflict among the displaced population located in Meta, as well as additional difficulties in accessing mental healthcare services, compared to other parts of the country.

Very few studies, whether national or international, show comparisons of the mental health outlook of displaced populations between regions and the entire country. Most studies analyse the prevalence in a single region. Torres et al.37 studied 18 departments in Colombia where, applying the SRQ to 11,990 adults, the rate of possible mental health disorder (SRQ+) was around 32% in the displaced population. This SRQ+level is much higher than the ENSM SRQ+rates for displaced population and, although to a lesser extent, is also higher than the rates found in our study. Puertas et al.38 also used the SRQ tool to measure trends in mental health in the displaced population and reported a 27.2% rate of common mental disorders, similar to our findings. Lastly, Gomez-Restrepo et al.39 made comparisons in mental health between regions with different exposure to conflict through national historical data. They found a prevalence of 10.8% for any mental disorder compared to 6.4% in non-conflict territories, measured with the Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Although their study does not focus only on the displaced population, their results are consistent with our findings that suffering mental disorders is more likely in populations affected by conflict. These studies, combined with our analysis of a region affected by conflict such as Meta, provide preliminary analyses of differences in mental health in conflict areas compared to the national averages found in the 2015 ENSM.

These results show that, although the 2015 ENSM gives a general overview, the mental health situation in regions greatly affected by conflict, such as Meta, may be more critical. Future studies should therefore identify potential vulnerability factors, which particularly worsen the mental health of the displaced population,40–42 limit their adequate access to mental health services43–45 or lead to a higher rate of mental health problems in the most vulnerable members of this population, such as women, older adults and children.46–48

External validityOur study involved a local analysis in a single region, which was Meta. Our results therefore need further analysis in future studies in other regions, to determine whether or not there are similar trends in mental health in the displaced population in other areas affected by conflict. It is also important to verify whether or not, as in our study, the incidence of possible mental disorders is higher than that found in the 2015 ENSM. Nevertheless, the representative nature of our survey, not only for covering urban and rural areas, but also the impact of the conflict in the municipalities where respondents were living, meant we were able to gain a truer understanding of the effects armed conflict has had on the mental health of displaced populations. As the armed conflict has affected different parts of Colombia in different ways, and the consequences on the mental health of the displaced population may also therefore be different, it could be very useful for future studies to examine whether or not the mental health scenario in these regions and, in particular, in the displaced population, coincides with our findings in the department of Meta.

ConclusionsThe comparative approach adopted in our study highlighted differences in mental health in a region like the department of Meta historically affected by conflict, and identified from an exploratory point of view differences with the national mental health scenario. The analysis of this particular case has identified significant differences in mental health that can often remain hidden when examining the general mental health picture in Colombia overall. Such generalisation can hide considerable differences in mental health in the most vulnerable populations, as well as in districts most affected by violence.

Mental health problems are both a cause and a consequence of poverty, poor education, gender inequalities, violence and other global development challenges.49 A greater focus on mental health within global development policies makes it possible to place the individual at the centre of development50 and at the same time make the problem more visible. For many years this was an "invisible problem in international development",51 but it is now recognised as one of the biggest “obstacles” to achieving most development goals.52 Based on our findings, we therefore consider it important to design public policies aimed at addressing these problems where the individual is at the centre of development. Such policies need to particularly address the care of the displaced population, which is at greater risk of suffering these disorders and has to deal with situations affecting their mental health-related quality of life on a daily basis.

FundingProject funded by the UK Medical Research Council, Economic and Social Research Council, DFID and Wellcome Trust (Joint Health Systems Research Initiative, Grant MR/R013667/1).

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.