This research described the perspective of illicit drug users regarding illicit drug use prevention initiatives. The study used a convergent parallel mixed methods design, combining quantitative and qualitative methods. In the quantitative component of the study, 111 subjects from a psychosocial care centre (CAPS-AD). The qualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews with 11 subjects who were selected from among the participants and who declared themselves to be personally affected as being or having been illicit drugs users. From the perspective of drug users, the results pointed out different prevention initiatives and the institutions that should be responsible for them. For preventive actions to be successful, they must be intersectoral and involve government, community and families.

Esta investigación describió la perspectiva de los consumidores de drogas ilícitas con respecto a las iniciativas de prevención del consumo de drogas ilícitas. El estudio utilizó un diseño de métodos mixtos paralelos convergentes que combina métodos cuantitativos y cualitativos. En el componente cuantitativo del estudio, 111 sujetos de un centro de atención psicosocial (CAPS-AD). Los datos cualitativos se recogieron a través de entrevistas semiestructuradas con 11 sujetos que fueron seleccionados entre los participantes y que se declararon personalmente afectados por ser o haber sido consumidores de drogas ilícitas. Desde la perspectiva de los usuarios de drogas, los resultados señalaron diferentes iniciativas de prevención y las instituciones que deberían encargarse de ellas. Para que las acciones preventivas tengan éxito, deben ser intersectoriales e involucrar al gobierno, la comunidad y las familias.

Illicit drugs use continues to grow as a public health problem because of its harmful effects on individuals and communities. Illicit drugs include substances that are prohibited under international law, such as amphetamine type stimulants, cannabis, cocaine, heroin and other opioids, and ecstasy.1 In addition, such substances are illegal due to the problematic effects or consequences caused by any of its components.2

Illicit drug use is a key issue in national and international agendas, causing damage to health, society and the economy in general, interfering in internal development and in the relationship between countries. Besides that, the intensification of illicit drug trafficking remains a serious issue, associated with violence and therefore requiring the redefinition and improvement of actions for its combat as well as the promotion of respect for human rights.3

Around 247 million people worldwide use illicit drugs4 and illicit drug use directly accounts for 0.8% of global disability-adjusted life years.1 Also, according to the 2019 World Drug Report, approximately 35 million people suffer from drug use disorders and require treatment.5 In Brazil, according to data from the II National Survey on Drug Use and Health-II LENAD6, with regard to illicit drugs, there is a prevalence of marijuana use among the adult population of 6.8%, corresponding to 7.8 million Brazilians, followed by the consumption of cocaine (3.8%) and stimulants (2.2%).

Based on the reality described, it is essential to address the issue of drug prevention in Brazil, considering the Brazilian importance in global drug trade and the accessibility of these substances in the country. Prevention comprises processes to promote well-being, growth and optimal development at individual, family and community levels. It aims at foreseeing problems, enabling early intervention, avoiding drug use, strengthening protective factors, and decreasing risk factors.7–9 Prevention can be broadly categorized as risk reduction, harm reduction, demand reduction and health promotion. Effective prevention requires a broader health promotion approach and has to be linked to other drug control responses in order to achieve long-term benefits.10

Preventing substance use is one of the key components of a public health approach. Substance use prevention has the potential to prevent or reduce substance use, as well as social conditions and negative health consequences that affect individuals and society.11

In this sense, extensive efforts have been and continue to be made by governments and nongovernmental organizations at all levels to eliminate and prevent illicit drug production, consumption, trafficking, and distribution. The United Nations Office on Drugs and crime recommends that the most effective action to address the illicit drug problem is to coordinate a comprehensive and balanced approach in which the provision, control and demand reduction are mutually reinforcing. In addition, experiences around the world have shown that substance use and related problems cannot be significantly prevented or reduced by any single, limited measure.12

Measures are being adopted at international and national levels against the demand for illicit drugs. To be effective, these approaches require goal-oriented strategies that are inherently positive.13–15 The main focus of these measures is to reduce the use of illicit drugs among young people who are not at risk, as well as in more vulnerable groups.16

Measures for the prevention of illicit drugs should value the context in which illicit drug users take part, in order to direct actions of prevention. Based on these considerations, this study aimed to describe the perspective of illicit drug users regarding initiatives to prevent illicit drug use.

MethodsThe study represents the continuity of a multi-center project that aimed at identifying the critical perspective of family members and significant others to illicit drug users in seven Latin American countries and Canada. The project focused on risk and protective factors, prevention initiatives, services and treatments and laws and policies on illicit drugs.

Considering the data obtained from the research with family members and significant others to illicit drug users, it was also important to understand the perspective of illicit drug users themselves and to compare the data from the 2 studies. This article presents the results obtained in an inner city of the state of São Paulo, Brazil, with regard to prevention initiatives from the perspective of illicit drug users.

The study design combined the quantitative and qualitative methods, with a view to exploring the different aspects of the participants’ life experiences. The combination was based on the acknowledgement that the methods are complementary and possess distinguished strengths, so that convergences can be compared and the results confirmed.17

Participants and recruitmentThe population of this study is comprised of adults over the age of 18 who identified themselves as personally affected because they are or have been illicit drugs users. The study included a total of 111 illicit drug users recruited from a psychosocial care centre (CAPS-AD) using a convenience sample. The sample size of 111 participants was chosen based on the resources available locally and to ensure sufficient variation in participants’ characteristics and experiences. Three interviewers were selected and trained on how to approach and interview the participants, as well as to fill out the data collection form, according the literature on the topic.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe inclusion criteria were as follows: men and women over 18 years of age who self-identify (and are perceived by researchers) with the cognitive skills necessary to participate in research, who use or have already used illicit drugs during the course of their lives. The exclusion criteria were people who were identified as not possessing the cognitive skills necessary to participate in research, or people who at the time of the interview were under the influence of some substance could impair their participation in the study.

Quantitative dataQuantitative data were collected through an instrument with closed questions, documented on paper and filled out by the researcher or selected research team member. The questionnaire contained questions on socio-demographic data (sex, marital status, religion, social network, schooling, occupation, housing conditions, family income and living conditions) and questions on prevention initiatives. The instrument was not submitted to psychometric testing. Questions related to the usefulness of giving people opportunities to prevent illicit drug use required a “yes”, “no”, and “do not know” response scale. Other questions related to the responsibility of institutions in prevent people in general from having problems with the use of illicit drugs, used a Likert scale.

Qualitative dataQualitative data were collected through semi-structured interviews followed by a guide with 7 questions, one of them regarding preventive initiatives for drug use. The purpose of these questions was to better understand how people describe, act, and deal with everyday situations related to illicit drug use issues.18 Among the participants who participated in the quantitative part of this study, a convenience sample of 11 subjects were invited to participate in the interviews.

The interviews were recorded, documented and transcribed. The interview transcripts were identified by numeric codes and names were replaced by “Interviewer 1 (I1), Interviewer 2 (I2), …” to protect participants’ identities.

Data analysisTo standardize the data capture, a form was developed in the EpiData program. Quantitative and qualitative data were analyzed separately and later in triangulation. The quantitative data were analyzed statistically with the support of the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS®). The qualitative data were tape-recorded and then transcribed to assure quality control and the precise reproduction of the contents. Hence, after the transcription, the interviews were again checked and read to guarantee information precision, complete existing gaps, correct imprecisions and start the process of getting familiar with the data. The interview transcripts were identified with the help of numerical codes. The study was conducted with the permission of the local ethics committee, subject to Resolution No. 580/18 on the ethical requirements for research with human beings, with protocol number/CAAE: 50641415.7.0000.5393.

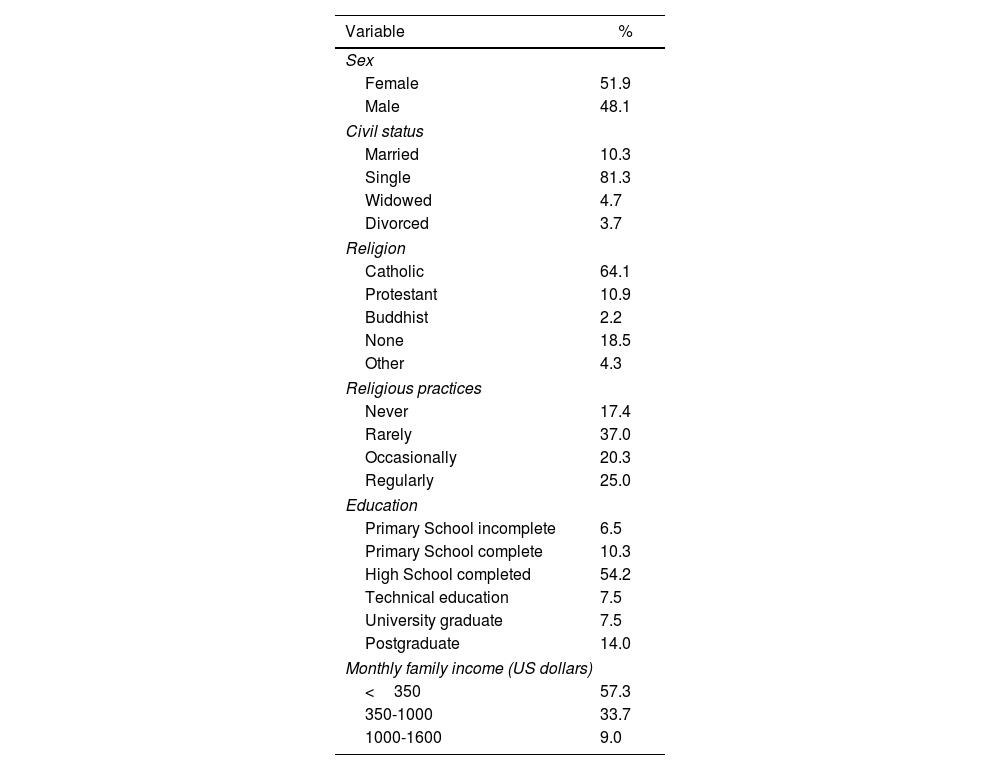

ResultsCharacteristics of the study participantsWith regard to demographic characteristics, 51.9% of participants were male and 48.1% female; 81.3% were single and 10.3% married; 54.2% finished secondary education; 64.1% were Catholic and 34% rarely practised their religion. Respondents were active in various professions (administrative, financial or clerical; sales or service; trades, transport or equipment operator; homemaker) and 11.5% worked with sales or service; 41.8%% had been employed in the same job for more than 2 years; 56.9% owned their houses; 66.7% lived with their relatives, and 57.3% earned less than 1000 US dollars per month.

With regard to the illicit drugs use, there was a prevalence of marijuana (93.6%), followed by crack/cocaine (32.3%), hallucinogens (24%), amphetamine/other stimulants (18.2%), benzodiazepines (15.2%), heroin/opium (4.1%) and prescribed opioids (3.1%). Some participants used more than one illicit drug.

Data on the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of participants (n=111) who are illicit drug users.

| Variable | % |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 51.9 |

| Male | 48.1 |

| Civil status | |

| Married | 10.3 |

| Single | 81.3 |

| Widowed | 4.7 |

| Divorced | 3.7 |

| Religion | |

| Catholic | 64.1 |

| Protestant | 10.9 |

| Buddhist | 2.2 |

| None | 18.5 |

| Other | 4.3 |

| Religious practices | |

| Never | 17.4 |

| Rarely | 37.0 |

| Occasionally | 20.3 |

| Regularly | 25.0 |

| Education | |

| Primary School incomplete | 6.5 |

| Primary School complete | 10.3 |

| High School completed | 54.2 |

| Technical education | 7.5 |

| University graduate | 7.5 |

| Postgraduate | 14.0 |

| Monthly family income (US dollars) | |

| <350 | 57.3 |

| 350-1000 | 33.7 |

| 1000-1600 | 9.0 |

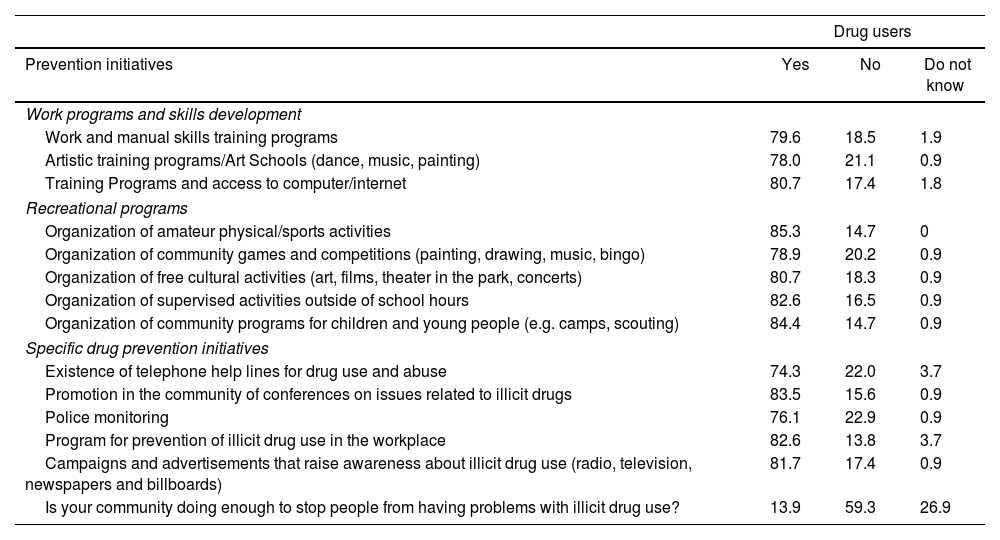

The questions on prevention initiatives were focused on the opinions illicit drug users had about different strategies that would help to prevent illicit drug use, as well as the perception of the effectiveness of the strategies developed at the community level for the prevention of illicit drug use. Data regarding prevention initiatives related to illicit drug use are presented in Table 2.

Opinion on illicit drug use prevention initiatives from perspective of illicit drug users (n=111).

| Drug users | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevention initiatives | Yes | No | Do not know |

| Work programs and skills development | |||

| Work and manual skills training programs | 79.6 | 18.5 | 1.9 |

| Artistic training programs/Art Schools (dance, music, painting) | 78.0 | 21.1 | 0.9 |

| Training Programs and access to computer/internet | 80.7 | 17.4 | 1.8 |

| Recreational programs | |||

| Organization of amateur physical/sports activities | 85.3 | 14.7 | 0 |

| Organization of community games and competitions (painting, drawing, music, bingo) | 78.9 | 20.2 | 0.9 |

| Organization of free cultural activities (art, films, theater in the park, concerts) | 80.7 | 18.3 | 0.9 |

| Organization of supervised activities outside of school hours | 82.6 | 16.5 | 0.9 |

| Organization of community programs for children and young people (e.g. camps, scouting) | 84.4 | 14.7 | 0.9 |

| Specific drug prevention initiatives | |||

| Existence of telephone help lines for drug use and abuse | 74.3 | 22.0 | 3.7 |

| Promotion in the community of conferences on issues related to illicit drugs | 83.5 | 15.6 | 0.9 |

| Police monitoring | 76.1 | 22.9 | 0.9 |

| Program for prevention of illicit drug use in the workplace | 82.6 | 13.8 | 3.7 |

| Campaigns and advertisements that raise awareness about illicit drug use (radio, television, newspapers and billboards) | 81.7 | 17.4 | 0.9 |

| Is your community doing enough to stop people from having problems with illicit drug use? | 13.9 | 59.3 | 26.9 |

In most items related to prevention initiatives, illicit drugs users gave more affirmative answers regarding prevention of illicit drug use. Among the participants, 85.3% identified organization of amateur physical/sports activities, followed by 84.4% who said that programs should be developed through the organization of community programs for children and young people and 83.5% selected the item related to the promotion in the community of conferences on issues related to illicit drugs. About the organization of supervised activities outside of school hours, 82.6% agreed on its importance. The program for prevention of illicit drug use in the workplace was reported by 82.6% participants as being part of specific prevention strategies.

Participants also stated that campaigns and advertisements that raise awareness about illicit drug use (81.7%), as well as the organization of free cultural activities (80.7%), training programs and access to computer/internet (80.7%), and work and manual skills training programs (79.6%), are prevention initiatives that help people to prevent illicit drug use.

Organization of community games and competitions were cited by 78.9% participants as a prevention initiative, followed by artistic training programs/art schools (78%) such as dance, music, and painting. Moreover, police monitoring (76.1%) and existence of telephone help lines for drug use and abuse (74.3%) were considered important drug prevention initiatives.

In addition, 59.3% of the participants indicated that the community was not “doing enough to prevent people from having problems with illicit drug use”.

In order to complement these results, the qualitative data pointed at prevention initiatives for the use of illicit drugs, actions to be developed in the community, at some work programs, recreational programs and specific initiatives. Besides that, they also indicated what could be done to help people to avoid the use of illicit drugs, highlighting issues related to accepting illicit drug users as human beings.

In relation to work and recreational programs, participants revealed that these programs related to work are opportunities for socialization, enabling them to feel useful in society and to have an occupation: “… to introduce a sport, a means of socialization, to feel useful… Do you know? To feel rescued, thus… because we are humans too… You know? I think that would help a lot” (I2). “I think the main thing is to keep people in activity, as it happens here at CAPS, for example, you fill your time with crafts, workshops, with, uh… with work, job. I think it helps a lot to get the person off, so I think I should broaden this range of activity. During this time you are working and doing crafts, you don’t smoke cigarettes, you don’t smoke marijuana. To offer jobs to survivors” (I3). “You have to put a person in the middle of field or in the middle a farm and make the person produce what they eat, so they can learn the concept of society, you know? Thus, they don’t have access to drugs, then you will really help people to recover” (I6). “You have to play sports, have fun, you know?” (I8).

Specific interventions to prevent illicit drug use have been linked to effective action through school and media campaigns to provide information to people on possible consequences of using illicit drugs: “To be effective it has to clearly demonstrate the consequences of illicit drug use. There have to be campaigns at schools with testimonies of users. Powerful campaigns are needed to show, just like with cigarette smoking, that it is bad, it gives cancer. The person reads the information needs to clearly indicate a person suffering with cancer as a result of illicit drug use. Such information should also be given via television. Television is a more practical and effective means, as is the personal testimony os the victims of drug use” (I8).

The participants also revealed information on prevention initiatives for illicit drugs use that exceeded the need for action through programs involving sports, job opportunities, the creation of artistic and cultural activities and the dissemination of information on the damage of illicit drugs. They showed the importance of welcoming, valuing the human being, assuring their dignity, listening, respect and acceptance as forms of prevention: “Once again I go back to this issue, we should fight for the human being, for the individual before their pathway is set in concrete, to save them from the pitfalls. But I think that in a certain way humanity as a whole should change, I think the focus should be on what you have. So I think this is complex, but with love, we can deal with what is coming, based on love and support. I mean that society has to embrace that individual” (I1). “The biggest step for us to stay abstinent, to be free of drugs, is to be accepted, you know? To accept yourself and to be accepted, thus you feel better, you will get stronger and not use drugs” (I2). “Get rid of it, uh, like we who are coming here at CAPS, being treated, have to do more for people who live on the streets, and to help these people who live on the street, having a good friendship, having knowledge, having respect for people, whether he has done drugs or not, has to have respect” (I10).

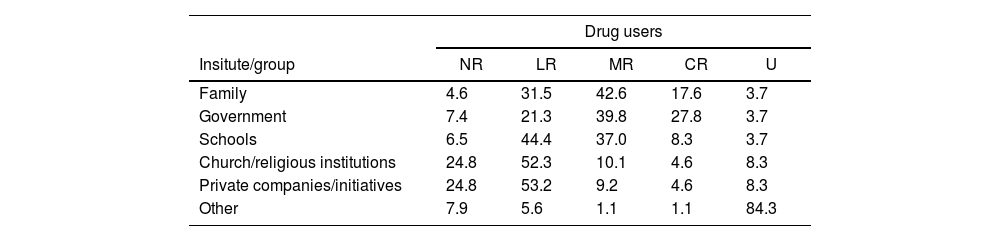

Institutions that contribute to the prevention of illicit drug problemsThe opinions of illicit drug users on the responsibility of institutions such as family, government, schools, church and religious institutions to prevent illicit drug use were given through a response scale “not responsible” (NR), “little responsibility” (LR), “mainly responsible” (MR), “completely responsible” (CR), or Unknown (U).

The results presented in Table 3 show that the majority of illicit drug users considered family and the government as MR for developing preventive actions, and pointed to schools, religious institutions and private initiatives as having LR for actions to prevent people from having problems with illicit drug use.

Opinion on institutional responsibility to prevent people having problems with illicit drug use (n=111).

| Drug users | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insitute/group | NR | LR | MR | CR | U |

| Family | 4.6 | 31.5 | 42.6 | 17.6 | 3.7 |

| Government | 7.4 | 21.3 | 39.8 | 27.8 | 3.7 |

| Schools | 6.5 | 44.4 | 37.0 | 8.3 | 3.7 |

| Church/religious institutions | 24.8 | 52.3 | 10.1 | 4.6 | 8.3 |

| Private companies/initiatives | 24.8 | 53.2 | 9.2 | 4.6 | 8.3 |

| Other | 7.9 | 5.6 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 84.3 |

Qualitative data emphasized the government's responsibility to prevent illicit drugs use, as well as the community as a whole: “Some hospital or something, you know? To help you, in my opinion, measures that can be taken in the middle of society to get people far from the drugs, for example, to create a government policy that gives nothing to anyone. But it isn’t necessary to wage a war against illicit drug users… they must have commitment” (I6). “The important thing is to make a more integrated community, whether in the religious or civil sector. It would be very relevant if the municipality, the state, the federation actually had programs that would show the practical side of the illicit drug in the sense of the dangerousness of the product” (I8).

DiscussionThis study aimed to describe the perspective of illicit drug users regarding illicit drug use prevention initiatives. Preventive initiatives and programs usually provide accurate and relevant information, encouraging interactive education, and developing skills as primary characteristics. Many prevention programs focus on schools, ranging from kindergarten through high school, being especially intensive before the age of first use.19

In this sense, prevention in schools was initially motivated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1970 when it convened several countries to discuss drug use and prevention. The school setting can act as a point of reference for the promotion of a lifestyle that distances people from drug use, since it enables the consolidation of values that are beneficial for the health of the community as well as in the identification of risk areas.20

School drug prevention programs use strategies that range from providing didactic drug information to developing psychosocial skills.21 Research results show that interactive prevention initiatives have been more effective than didactic information.22 However, to be effective, programs need to be aligned with the developmental stages of the intended target group (childhood, early, middle, or late adolescence).23

Studies that used interventions based on life skills training, including problem solving, coping with stressful situations, and developing social and communication skills, showed results beyond the prevention of drug use, such as the development of personal and social skills.24

When participants were asked about “Work programs and skills development”; the majority of them affirmed that these activities can be preventive initiatives. These activities can be developed through community-based drug abuse prevention programs, including a combination of school, family, mass media, public policy, and community organization components.25 Prevention focusing on community-level interactions is a strategy that increases power among its members and promotes greater engagement with local government organizations.26 Community involvement affects a person's sense of community, increasing leadership unity, community program engagement, and members’ perception of the community.27

The recreational programs, represented by free sports, cultural and community events, were seen as prevention alternatives by the majority of participants. The promotion of recreational activities can be an alternative to offer people well-being, contributing with the development of emotional abilities in the human being to deal with victories, frustrations, joys and sorrows.28 Thus, people with drug use problems can be socially isolated, have limited social support, and have disrupted lifestyle and relationships.29 Recreation-based mutual self-help groups can help improve a recovery identity regarding drug use.30

In addition, sports and other recreational activities allow the experience of new challenges, the development of joy, and the confidence to participate in life.31 Sports enable the formation of citizens conscious of the risks to which they are exposed, and aware of their own ability to choose a healthier lifestyle.32 In this sense, the formation of an autonomous person, capable of self development, must be established based on real situations that the individual lives daily and that involves the community.32

However, a study showed that sports practice can be presented as both a factor associated with protection and risk of drug use, depending on a series of variables, such as gender, sports, socio-cultural environment and motivation for both sports practice and drug use. Those planning preventive actions involving sports should consider the different factors involved in order to promote the prevention of drug use among adolescents.33

With regard to drug-specific prevention initiatives, the promotion of conferences on illicit drug-related issues in the community was the most consistent initiative. Information about drugs may be a powerful instrument to prevent young people from using drugs.34 From this perspective, information obtained from research conducted on the effects that drugs have on the brain and on people's behavior can help to develop projects aimed at preventing the abuse of these substances, as well as assisting in the treatment of users.35 The accessibility of information was recognized in this study, reinforced by the possibility of making it available in work environments, through law enforcement (police) and media.

Important initiatives have also made use of mass media campaigns. These campaigns have an effective communication potential and are educational tools.19 Young people report getting information about drugs on television, followed by parents and other print media. Mass-media campaigns are a powerful means for disseminating health promotion messages. In the field of drug addiction and dependence, advertisements may contribute to shaping patterns of drug use and the intention to use drugs, as well as modifying mediators such as awareness, knowledge and attitudes about drugs. However, a better understanding of which media interventions work best is likely to result in a more effective prevention of drug use and increased efficiency in the management of public resources.36

All participants said that they followed a religion, with a predominance of Catholicism expressed by 64.1%, but only 25% regularly practiced a religion. With this in mind, various studies identified that religion plays a fundamental role in the prevention of drug use, especially among young people.37 However, only 19.1% considered that church and religious activities help people to prevent problems with illicit drugs use, information that is not corroborated by of different investigations, clarifying that religion is a factor that prevents drug use among its adherents as it generates conceptions based on moral values with a focus on valuing life.34,38,39

When asked about the main institutions contributing to the prevention of illicit drug problems, participants mostly identified family and the government. Family-based initiatives, promoting family involvement and parent-child communication with parents serving as positive role models are strategies to prevent or reduce substance use among young people.40 Kumpfer reported that family-focused interventions were the most effective interventions for preventing drug use by young people. The average effect was 2-9 times greater than school based interventions that focused solely upon young people.41 Thus, those family interventions that combine parenting skills and family bonding components appear to be the most effective.25

The government was also pointed out by the participants as an important institution that contributes to illicit drug use prevention and this reality is corroborated by measures that are being adopted at international and national levels regarding the demand for illicit drugs. To be effective, these approaches require goal-oriented strategies that are inherently positive.13,15,42 The existence of these governmental strategies makes the prevention or reduction of drug use possible, as well as the identification of individuals who are already dependent in order to offer treatment and strategies for social reintegration.43,44 Social reintegration presents itself as a new way of thinking about practices and extra hospital care, without excluding the person from their family and community life.45

In Brazil, the Ministry of Health has been proposing actions and guidelines for the development of initiatives, at all levels of care, aimed at focusing on drug users. It is important, therefore, to understand these actions as well as the challenges for their realization. The development of actions committed to the promotion, education, prevention and follow-up of users and their families in the perspective of social integration, family and valuing of autonomous users not only contributes to reducing consumption, but also to reducing suffering caused by the consumption of such drugs in the various segments of society.46

These actions are in line with the characterization of prevention, operating at the primary level (reduction of drug-related risks), secondary level (reduction of drug-related harm based on existing problems) and tertiary level (preventing drug-related harm intensification).9,13 In this regard, efforts have been made by various sectors, at all levels, to suppress and prevent the use of illicit drugs.

ConclusionsIn general, the perspective of illicit drug users on prevention initiatives for illicit drug use in their social environment is represented by preventive actions focused specifically on drug use, the development of recreational programs, the organization of amateur physical/sports activities and organization of community programs for children and young people. The participants of this study considered families and governments the main institutions to prevent people from having problems with illicit drug use. This highlights the importance of the family in issues related to illicit drug use. Based on this reality, strategies to prevent the use of illicit drugs should focus on intersectoral actions, which should be subsidized through policy interventions and the involvement of illicit drug users, family and community.

Strategies to prevent the use of illicit drugs involving the family are considered successful when they focus on the relationship between parents and children, seeking to improve family dynamics, develop skills and resolve conflicts.47 Programs that use staging and live demonstrations on family issues related to the use of illicit drugs.48-50 Regarding community involvement, successful programs focus on making the community a more protective environment, including strategies aimed at parents, teachers and close people, with home visits, skills training, lectures, media campaigns and public policy planning for small communities.51 Community involvement can occur in different spaces and contexts, so research on the effectiveness of drug policies in the workplace indicates the use of strategies such as screening for problematic use of psychoactive drugs, motivational interview techniques and referral to treatment services in order to manage the moderate and severe risk of substance abuse.52 However, the effectiveness of different preventive programs needs to be compared and more research is needed to identify the feasibility and efficiency of prevention initiatives and the barriers faced during implementation.47 Besides that, personal, interpersonal and social participatory processes need to be developed, which identify and multiply different prevention initiatives discussed in this study, in order to enhance their effects and enable more effective strength-based approaches.

FundingCNPq - National Council for Scientific and Technological Development.

Conflict of interestsNone to be declared.