The article aims to describe the Mental Health Recovery Model, the Tidal Model in Mental Health Recovery and their relevance to implementation within the practice of Colombian nursing. Some concepts about mental health recovery and the theoretical model proposed by Phil Barker are presented in the text, analysing these with the challenges of the nursing professional to improve mental health care, taking into account the current context of care practice. The principles proposed with the Recovery model help to focus care on the person and not on the symptomatology of the illness, understanding that the person has different dimensions which make it possible for him/her to explore his/her own path to recovery. We can conclude that, through the theory, we can develop interventions and nursing activities that contribute to improving the quality of life of people who have been diagnosed with a mental illness, modifying the traditional healthcare models.

El objetivo es describir el modelo de recuperación de la salud mental (Recovery), el modelo de la marea en la recuperación de la salud mental (Tidal Model) y su relevancia hacia la implementación dentro de la práctica de la enfermería colombiana. Algunos conceptos sobre la recuperación de la salud mental y el modelo teórico propuesto por Phil Barker se presentan en el texto, y se analizan con los desafíos del profesional de enfermería para mejorar la atención de la salud mental, teniendo en cuenta el contexto actual de la práctica asistencial. Los principios propuestos con el modelo de recuperación ayudan a centrar los cuidados en la persona y no en los síntomas de la enfermedad, entendiendo que la persona tiene diversas dimensiones que le permiten explorar su propio camino hacia la recuperación. Se puede concluir que, a través de la teoría, pueden desarrollarse intervenciones y actividades de enfermería que contribuyan a mejorar la calidad de vida de las personas diagnosticadas de alguna enfermedad mental modificando los modelos tradicionales de atención sanitaria.

The World Health Organization (WHO) champions mental health promotion as a strategy for improving care quality and service management around the world.1,2 However, some traditional paradigms in the field of psychiatry have impeded the power of diagnosed persons to make decisions about their own treatment, especially drug treatment.3 This is evident in the false belief that there is no recovery from many of these diseases, such as schizophrenia, depression and bipolar disorder. Rehabilitation is held up as a person's only hope of reintegrating into society4; so-called neurocognitive impairment is the main argument for this.5 Diagnosis of a mental illness may be considered a catastrophic event,6 both for diagnosed persons and for their families,7 as when the disease is labelled and affirmed to be a lasting condition with a poor prognosis, their hope is shattered.8

Colombia and Latin American countries in general have limited experience in implementation of alternative care models, with the exception of countries such as Chile, Brazil, Panama and Argentina.9,10 Common obstacles to implementing these models include various health policies that organise care systems, reactions by mental health professionals who resist change11 and limited academic training of new generations in envisioning non-traditional care models.12

In the Colombian context, some laws — such as Law 1616, of 2013 (Ley de salud mental [Mental Health Law])13; Law 1448, of 2011 (Ley de víctimas y restitución de tierras [Victims and Land Restitution Law]); and Law 1098, of 2006 (Ley de infancia y adolescencia [Childhood and Adolescence Law]) — concern various mental health topics, hinting at great opportunities that can be taken advantage of through multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary efforts. The 2015 Estudio Nacional de Salud Mental en Colombia [Colombia National Mental Health Survey] emphatically affirmed that emergency measures are required not only to prevent the onset of mental illnesses but also to prioritise mitigating the impact of situations that cause mental health problems in Colombians, especially those in a state of vulnerability.

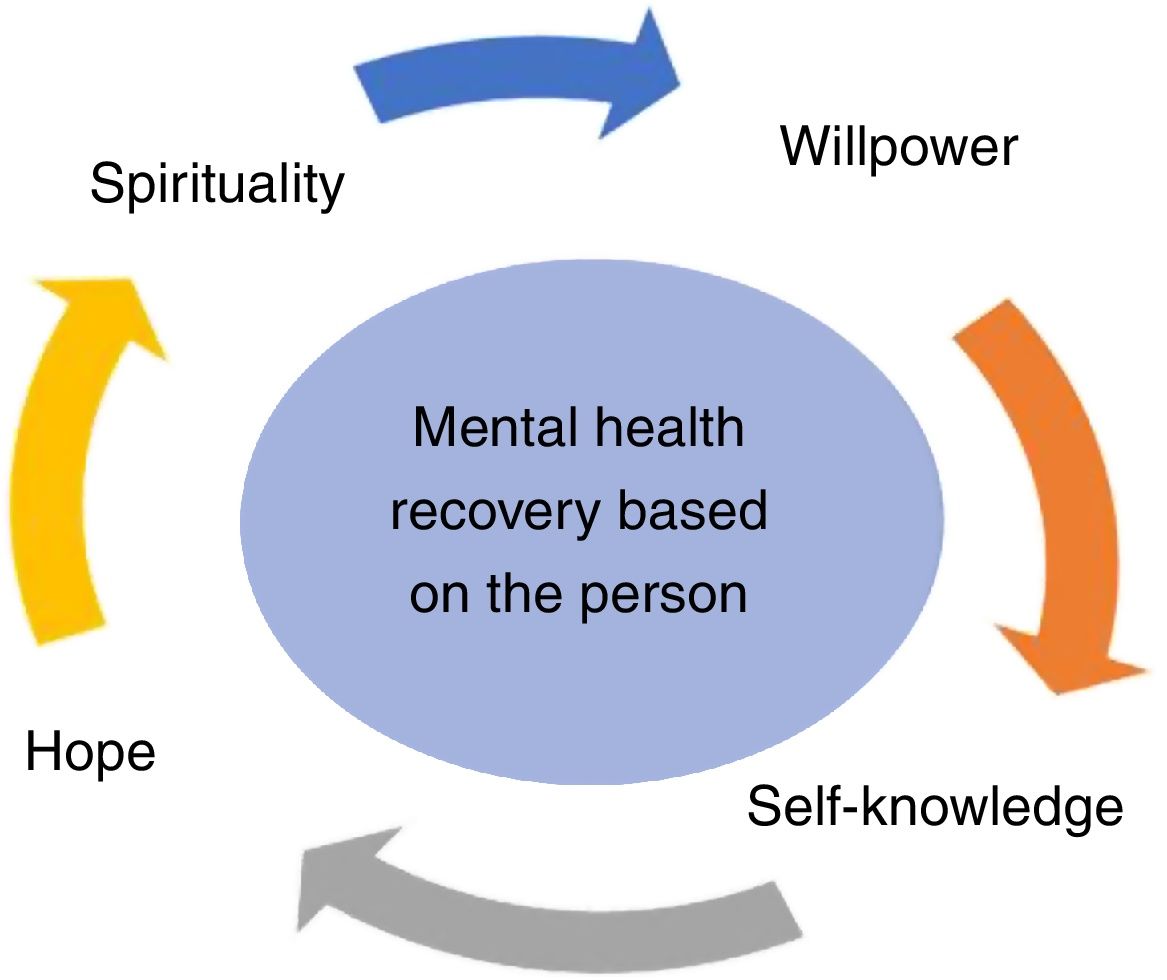

Mental health recoveryThe concept of mental health recovery has been gaining traction within the new healthcare standards. From the outset, it has promoted strengthening such qualities as willpower, spirituality, hope and self-knowledge to help the person find their own path to recovery.14 This concept moves away from an exclusive focus on mental disorders, which is very common in traditional psychiatric treatment models.15 The significance of a focus on mental health recovery lies in changes made by healthcare professionals in their approach to their work such that they see the person as a holistic being and do not fixate on the symptoms of their disorder. This enables so-called psychiatric "patients" to recover not only their state of health but also their dignity, self-esteem and well-being16 through strengthening qualities such as spirituality, hope, willpower and self-knowledge (Fig. 1).17

In some European countries, the concept of mental health recovery recognises that the person recovers their physical and social abilities in going about activities of daily living, and has become a defence of a personal search for strength through reflection and self-learning. These things are much more complex than symptoms of a disorder, and require various types of healthcare infrastructure.18

The idea that mental health recovery can be achieved with the influence of a single discipline lies far outside the ideals of comprehensive care sought with this approach.19 By contrast, collaborative efforts made by various professionals (social workers, nurses, occupational therapists, psychologists, speech therapists, physiotherapists and psychiatrists) have led to consideration of various perspectives in treatment, without imposing ideas on the person living with the diagnosis, who is, ultimately, the person who realises and determines the course of the process.18 This is undoubtedly a new approach to mental health care for the Colombian healthcare system, one that seeks to deliver person-centred care, alters various therapeutic spaces, humanises care and bolsters hope. It requires raising awareness of mental health recovery theory at all levels of training, which makes it easier to grasp and assimilate the model's therapeutic objective.20 In addition, it has been found that governmental support in different states of health is essential, as it facilitates incorporation of particular elements such as dialogue and the therapeutic relationship with the entire team at once.18

The Tidal Model of mental health recoveryPhil Barker and Poppy Buchanan-Barker are the leading theorists on the role of nursing within care models based on mental health recovery, having developed the Tidal Model of mental health recovery.14,21 Recognised as a middle-range nursing theory, the Tidal Model can be applied to professional practice and is the first model of mental health recovery that has been rigorously evaluated by the public sector.3,5

According to the theory, through instruments such as listening and dialogue, nursing and health professionals guide individuals in the recovery process.22 This idea is presented from a philosophical perspective; health professionals are invited to internalise the importance of the prior experiences, expectations and stories of the person suffering from mental health problems. It eschews an exclusive focus on symptoms in favour of reflection on and analysis of the crisis as something that enables a person to continue with the process on the so-called "path to recovery".23

This theory has been used in studies in various countries16,22,24 that have sought, in applying this model, to link nurses and various other mental health professionals with person-centred care,11 which should respect the person's rights, culture, life story and treatment expectations.25

The essential characteristics of the model are as follows26: a) collaborating with the person (and their family, as appropriate) in preparing their treatment plan — using this approach, treatment should be proposed from the perspective of the person living through a situation with repercussions for their mental health25 (it should be clarified that, through clear information on the different therapeutic approaches, the person and/or their family establishes the person's own life plan, which facilitates decision-making); b) empowering the person through narration of their experience, as such narration encourages the person to construct their own story, and this in turn encourages them to remember things that enable clarification of the various circumstances surrounding a crisis, which helps the person reaffirm their role as a player in a historical context in society and, to a certain extent, gives meaning to their existence — thus, narratives help the person construct their own story and actively develop a life plan; c) integrating nursing care with other disciplines — although clearly the nursing profession has collaborated with different health areas, emphasis is placed on the importance of generating a body of knowledge that does not just benefit a single discipline, but also benefits the person who receives care, which requires creating therapeutic spaces void of therapy jargon in which attention is centred on the person and each discipline contributes its grain of sand to the path that the person will traverse in their state of health throughout their life; and d) engaging in problem solving and promotion of mental health through narration based on individual and group interventions — others' experiences enable the person to appropriate elements that foster learning and represent a basic path towards self-knowledge,25 and based on this self-knowledge, the person manages to focus their attention on the circumstances surrounding the mental health problems they face, as well as factors that promote well-being, which manifest through narratives and may be expressed both in the experiences of others and in the person's own experiences.

The person is the key factor in their own recovery process, but the professional is the one who can help unlock enough potential for the person to reach this objective.23 The health professional helps by expressing "genuine curiosity" about the person — that is to say, a real desire to learn about a person's story.27 The Tidal Model is not problem-centred; it helps the person to develop and draw on resources that will aid them in their recovery process.25

Crises are recognised as opportunities to change and therefore to improve. The role of the health professional is to help the person view crises as events that aid them in directing their lives, and enable them to identify what they need in order to make a change so that crises do not recur.14

The model recognises that psychiatry is not the only profession that deals with treating mental health; it also plays a supporting role in other disciplines.26 On the other hand, there is a distinct difference between interdisciplinary and multidisciplinary invention. Interdisciplinary efforts are undertaken not separately but together with a specific, comprehensive goal.11,23

The Tidal Model features 10 commitments rooted in 10 fundamental values that represent the essence of the therapeutic process.11 Specific competencies which professionals should have and which facilitate the use of the model in practice are embedded in each36:

- 1

Value the voice: Allowing the person to tell their story on their own, not through others, alters the traditional landscape, which prioritises what the professional says and diverts attention from what the person says.

Competency 1: The professional demonstrates a capacity to listen actively to the story of the person with a mental health condition.

Competency 2: The professional is committed to helping the person make a detailed record of their personal story in their own words as part of the therapeutic process.

- 2

Respect the language: A fundamental aspect of the tidal model is respect for the person's colloquial language, since valuable elements that may contribute to the person's path to recovery may get lost in the technical terms used in psychiatry and psychology.

Competency 3: The professional allows the person to express themselves with their own language.

Competency 4: The professional helps the person to understand their experiences through personal stories, anecdotes and metaphors.

- 3

Become the apprentice: People are experts on their own life story; therefore, the professional carer should respect and should choose to learn from that experience.

Competency 5: The professional designs a care plan based on the needs expressed by the person.

Competency 6: The professional helps identify problems and/or needs that affect the person and helps propose solutions.

- 4

Use the available toolkit: The person's story features things that have worked and others that have not. The professional will help the person use instruments and put them in practice on their path to recovery.

Competency 7: The professional helps the person identify what is helping them and what is not in specific problems in their life.

Competency 8: The professional shows an interest in identifying which people in the person's life could aid in their therapeutic process.

- 5

Craft the step beyond: Any step that the person takes will help them recover. Developing objectives, no matter how simple, will help them advance and not get stuck, which will shorten the recovery process.

Competency 9: The professional will help identify the consequences of what taking a step means for solving the problems in the person's life.

Competency 10: The professional helps the person identify their short-term needs so that they have the experience of "taking a step" towards solving those problems.

- 6

Give the gift of time: The person must be given sufficient time. Nothing is more important than being generous with time when a person is trying to tell a story. This is all the more true when that person is relating their own experiences. The professional must be clear on this.

Competency 11: The professional helps the person identify that the time dedicated to solving their problems is of great value.

Competency 12: The professional recognises the time that the person dedicates to their own therapeutic process.

- 7

Develop genuine curiosity: When the person is telling their story, the professional should show real interest in hearing it.

Competency 13: The professional is interested in the person's life story and asks them to elaborate on important matters and details.

Competency 14: The professional shows the person their interest in helping them, but lets them tell their story at their own pace.

- 8

Know change is constant: One of the fundamental aspects of the recovery process is knowing that everything changes and that this change is inevitable. The role of the professional is rooted in helping the person understand that change is inevitable but growth is optional. The professional also supports the person in making decisions that help them deal with change on their path to recovery.

Competency 15: The professional helps the person identify changes in their thoughts, feelings and/or actions.

Competency 16: The professional helps the person to identify how they, other people and certain situations influence changes in the person.

- 9

Reveal personal wisdom: That experience which the person possesses turns into wisdom, and it is precisely when they are shown it that they start on their path to recovery.

Competency 17: The professional helps the person recognise strong and weak points in their therapeutic process.

Competency 18: The professional helps the person develop self-confidence and the capacity for self-help through the therapeutic process.

- 10

Be transparent: The person and the professional carer should take a genuine interest in working together. A safe environment that allows the person and the professional to communicate freely should be created.

Competency 19: The professional ensures that the person is aware of the purpose of the therapeutic process.

Competency 20: The professional ensures that the person receives a copy of all documents relating to the therapeutic process.

A very important characteristic of this model is that the term "patient" or "client" is changed to "person" or "cared for person" so as to emphasise the fact that they have rights, feel, get emotional and experience life as any other human being does.26 There is no hierarchy in the therapeutic relationship, as all are learning and complementing one another, even those whose experience renders them experts and enables them to help others.11

DiscussionWithout a doubt, various difficulties and problems in the community with respect to people's mental health currently exist and have been increasing in recent years. The family, as the primary network responsible for the direct care of people with a mental disorder, not only aids in administration and taking of medications, accompaniment to follow-up visits and day-to-day care, but also promotes comprehensive care, which involves diet monitoring, communication at home, support in decision-making and identification of roles, among other things.28 The nursing professional aids in activating various sources of support which may help with treatment and treatment continuity.

In general, professional training in mental health nursing has revolved around knowledge imparted by psychiatry and conventional biomedical models14,29; this undoubtedly turns professional practice into an instrument with greater benefits for treating disorders than for providing person-centred care.11 Furthermore, the limited number of mental health nursing professionals in Colombia and the Americas in general30 creates a complex landscape that impedes improvement in and qualification for services.31

The responsibility of the nursing profession in mental health recovery for people who have experienced difficulties that have altered their mental health lies in the very need to show that, as a scientific discipline, nursing is involved in every stage of the process,11 thus dispensing with the notion that the place of nursing is limited to the diagnosis and drug treatment stages.17 Each and every one of the efforts made by nursing professionals around the world has a purpose: caring for people. Thus, nursing professionals are crucial within the mental health/disease dynamic, as they are capable of establishing a connection between the biological, psychological, social, cultural and spiritual dimensions of a person.14

In many cases, psychiatric hospitalisation is necessary when it becomes impossible for the family to provide home care (understood as activities involved in managing a person's treatment, including adherence to drug treatment and diet plans and accompaniment to follow-up appointments).32 To this is added the fact that the diagnostic label "psychiatric disorder" is socially rejected in most cases,33 which creates in the family unit a number of internal conflicts triggering an emotional response that results in anguish and despair.28 In most cases, carer burnout can set in, distancing individuals from their family members and leaving them in a vulnerable state that makes recovery slower and more difficult. This is a point at which the professional may intervene and use this theory to provide compassionate, humanised care.34

Developing care protocols that include the various competencies in this theory helps health institutions to envision a care model that differs from traditional care models, which have demonstrably struggled to implement humanised, person-centred actions as opposed to actions focused on mental disorders.23 It is also essential for personnel working in mental health to take on these commitments in order to provide comprehensive care and recognise the person's experience as an important factor in the therapeutic process.24

ConclusionsThe principles of the recovery-centred mental health care model are rooted in the realisation of person-centred care. Through application of the model and narration of the person's life story, nursing and health professionals can help the person identify aspects of their attitudes and behaviours in various disease stages that led to the onset of a crisis and mechanisms used to cope with the difficulties caused by their symptoms.

Healthcare personnel guide and support individuals towards recovery of their mental health. Qualities such as hope, willpower, spirituality and self-knowledge aid in going about a process of personal fulfilment aimed at formulating a life plan, which gives meaning to the person's existence and promotes their subjective well-being.

In Colombia, various problems would complicate implementation of a model of this type. However, it is essential to create a space for discussion on this topic, as it represents an opportunity to make changes particular to various epistemological paradigms that have long underpinned healthcare practice and must be modified so that health professionals, especially nursing professionals, may come closer to providing comprehensive, holistic care.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Morales DRZ, Moreno JRC. El modelo de recuperación de la salud mental y su importancia para la enfermería colombiana. Rev Colomb Psiquiat. 2020;49:305–310.