Peripheral spondyloarthritis is a chronic inflammatory disease whose clinical presentation is related to the presence of arthritis, enthesitis and/or dactylitis. This term is used interchangeably with some of its subtypes such as psoriatic arthritis, reactive arthritis, and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis.

ObjectiveTo develop and formulate a set of specific recommendations based on the best available evidence for the diagnosis, treatment, and monitoring of adult patients with peripheral spondyloarthritis.

MethodsA working group was established, clinical questions were formulated, outcomes were graded, and a systematic search for evidence was conducted. The guideline panel was multidisciplinary (including patient representatives) and balanced. Following the formal expert consensus method, the GRADE methodology “Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation” was used to assess the quality of the evidence and generate the recommendations. The clinical practice guideline includes ten recommendations related to monitoring of disease activity (n = 1) and treatment (n = 9).

ResultsIn patients with peripheral spondyloarthritis, the use of methotrexate or sulfasalazine as the first line of treatment is suggested, and local injections of glucocorticoids are conditionally recommended. In patients with failure to cDMARDs, an anti TNFα or an anti IL17A is recommended. In case of failure to bDMARDs, it is suggested to use another bDMARD or JAK inhibitor. In patients with peripheral spondyloarthritis associated with inflammatory bowel disease, it is recommended to start treatment with cDMARDs; in the absence of response, the use of an anti TNFα over an anti-IL-17 or an anti-IL-12-23 is recommended as a second line of treatment. In patients with psoriatic arthritis, the combined use of methotrexate with a bDMARD is conditionally recommended for optimization of dosing. To assess disease activity in Psoriatic Arthritis, the use of DAPSA or MDA is suggested for patient monitoring.

ConclusionsThis set of recommendations provides an updated guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of peripheral spondyloarthritis.

La espondiloartritis periférica es una patología inflamatoria crónica cuya presentación clínica está determinada por la presencia de artritis, entesitis y/o dactilitis. Este término se utiliza indistintamente con algunos de sus subtipos como artritis psoriásica, artritis reactiva y espondiloartritis indiferenciada.

ObjetivoDesarrollar y formular un conjunto de recomendaciones específicas basadas en la mejor evidencia disponible para el diagnóstico, el tratamiento y el seguimiento de pacientes adultos con espondiloartritis periférica.

MétodosSe constituyó un grupo desarrollador, se formularon preguntas clínicas, se graduaron los desenlaces y se realizó la búsqueda sistemática de la evidencia. El panel de la guía fue multidisciplinario (incluyendo representantes de los pacientes) y balanceado. Siguiendo el método de consenso formal de expertos, se utilizó la metodología GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) para para evaluar la calidad de la evidencia y generar las recomendaciones. La guía de práctica clínica incluye diez recomendaciones: una sobre seguimiento de la actividad de la enfermedad y nueve sobre tratamiento.

ResultadosEn pacientes con espondiloartritis periférica se sugiere usar metotrexato o sulfasalazina como primera línea de tratamiento y se recomienda en forma condicional la inyección local de glucocorticoides. En los pacientes que fallan a cDMARDs, se recomienda iniciar un anti TNFα o un anti IL17A. Ante falla terapéutica a la primera línea con bDMARDs, se sugiere usar otro bDMARD o un inhibidor JAK. En pacientes con espondiloartritis periférica y enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal asociada, se recomienda iniciar tratamiento con cDMARDs; en ausencia de respuesta, se recomienda el uso de un anti TNFα sobre un anti IL-17 o un anti IL-12-23 como segunda línea de tratamiento. En pacientes con artritis psoriásica se recomienda, de forma condicional, el uso combinado de metotrexato con bDMARD para favorecer la optimización de la dosis de estos. Para evaluar la actividad de la enfermedad en artritis psoriásica, se sugiere el uso del DAPSA o MDA para el seguimiento de los pacientes.

ConclusionesEste conjunto de recomendaciones proporcionan una guía actualizada sobre el diagnóstico y el tratamiento de la espondiloartritis periférica.

Spondyloarthritis (SpA) is a generic term comprising a group of underlying inflammatory conditions that share clinical, genetic, epidemiological, pathophysiological and therapeutic response characteristics. Based on their clinical presentation, these conditions may be peripheral or axial; the age of onset is usually before 45 years old. Peripheral spondyloarthritis (pSpA), as a subtype of spondyloarthritis, is a chronic inflammatory condition clinically characterized by the presence of arthritis (oligoarthritis predominantly of the lower extremities), enthesitis (site of attachment of a tendon, ligament, or joint capsule to the bone) and/or dactylitis (sausage fingers). The classification criteria Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society substantially changed the phenotypical approach, also referred to as the “SpA concept”, by a more accurate classification for the peripheral presentation associated with the predominant symptomatology.1 However, the ESSG classification criteria may also be useful in various clinical settings.2

The term SpA is used indistinctively with some of its subtypes, such as psoriatic arthritis (PsA), reactive arthritis and undifferentiated SpA. However, the hallmark of pSpA is the presence of peripheral symptoms (arthritis, enthesitis and dactylitis) but it is not pathognomonic, since these may also be present in patients with axial SpA.3

Several studies in Colombia have reported different clinical presentation patterns in pSpA and their more frequent manifestations, assessing the performance of the different classification criteria and using the rheumatologists clinical diagnosis as the external standard.4

The data associated with the clinical presentation patterns in pSpA, in contrast to the data extrapolated from PsA studies, are limited. The diagnostic delay is shorter than axial SpA because patients with peripheral manifestations usually present with clinically objective inflammatory signs (arthritis and/or dactylitis). The age of onset of symptoms is delayed as compared against axial spondyloarthritis and the gender distribution is the same.5 Among the typical manifestations of pSpA, dactylitis is a hallmark of PsA.6

Among the extra-articular manifestations, psoriasis is the most common one (43–53%), followed by inflammatory bowel disease (4–17%) and acute anterior uveitis (2–6%). Inflammatory lumbar pain which is a prevalent characteristic in patients with axial SpA has also been reported in 12.5% of the patients with PsA and in up to 21% in pSpA.7

The prevalence of SpA in Latin America has been estimated at about 0.14 (95% CI: 0.05−0.34).8 A recent study conducted in Colombia using the Copcord methodology, estimated a prevalence of 0.11% for SpA and of 0.28% for undifferentiated SpA.9

In addition to the extra-articular manifestations (uveitis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease), the associated comorbidities in these patients increase the total burden of the disease, particularly in terms of cardiovascular and infectious diseases.10

The main treatment objective in SpA is to maximize the long-term health-related quality of life by controlling signs and symptoms (pain, morning stiffness, and fatigue) and inflammation (disease activity), in addition to the prevention of progressive structural damage (osteo-proliferative and osteo-destructive changes in the peripheral joints), preserving function (spinal mobility) and social participation (activity and productivity).11 However, the treatment of patients with pSpA represents a challenge to the clinician because of the heterogenous nature of the clinical manifestations and the subtypes included in the definition, which significantly influence the therapeutic decisions for each individual patient.3

This is the first clinical practice guideline (CPG) developed, published and implemented in Colombia, for patients with pSpA; its objective is to make specific recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of these patients. The CPG are addressed to all healthcare professionals involved with the care of patients with pSpA, decision-makers, healthcare payers and government institutions developing health policies. The complete version of the CPG (included the methodology developed, the systematic search for scientific information and the detailed presentation of the evidence) is available in the supplemental material and may be accessed through the website of the Colombian Association of Rheumatology (Asoreuma) and the webpage of the scientific societies of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection of Colombia, following the publication of this document.

Materials and methodsThe main purpose of this CPG is to develop and design specific recommendations supported by the best available evidence associated with the diagnosis and treatment of adult patients with pSpA. The intent is to standardize diagnostic and monitoring approaches, to create awareness of the medical practitioners about the identification and clinical suspicion of the disease, reduce the treatment variability by rationalizing expenditure, optimizing timely referral of patients to the rheumatologist, and improving quality of life and occupational and social performance of these patients.

In accordance with the formal consensus methodology suggested by the Methodological Guidelines for the development of comprehensive care guidelines of the Colombian General Healthcare System,12 the experts panel approach was selected to produce the recommendations.

The Guidelines Development Team (GDT) assessed the accuracy of the evidence, developed and graded the recommendations, pursuant to the approach suggested by the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE [GRADEwg]) work group.13–16

Organization, planning and coordination of the clinical practice guidelinesThe GDT comprised 9 expert rheumatologists and one immunology bacteriologist, members of the Asoreuma Spondyloarthritis Study Group, 2 representatives of patients one anthropologist as the civil society representative. All the panel sessions were joined by representatives of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection and of the Institute for the Assessment of Health Technologies (IETS). The leader of the GDT was a rheumatologist representing the Asoreuma study group. The development of the CPG was under the methodological oversight of an external independent consulting firm — Evidentias SAS. The CPG were developed according to the recommendations of the Methodological Guidelines for Preparing Clinical Practice Guidelines and economic evaluation of the Colombian Social Security system.12 The work of the GDT was conducted using IT tools, on-site meetings, and virtual meetings. Evidentias assisted the process for the development of the guidelines, including the identification of the methodology, the preparation of the agendas for the meetings, the materials, moderating the discussion panel sessions, in addition to summarizing and assessing the evidence to systematically respond to each question of the guidelines and producing the final documents.

Sponsorship of the clinical practice guidelines and addressing conflicts of interestThe development of the CPG was possible due to the unrestrictive support of the following organizations which together funded the project: Abbvie, Amgen, Janssen, Novartis and Pfizer. The technical work for the development process of these CPG was independently conducted by the GDT.

The disclosure of possible conflicts of interest by each GDT member was explicitly made at the beginning of the process for the development of the CPG, and also before the start of the meetings to produce the recommendations suggested by all of the participants. No conflict of interests was disclosed which preventing the participation or vote of any of the GDT members.

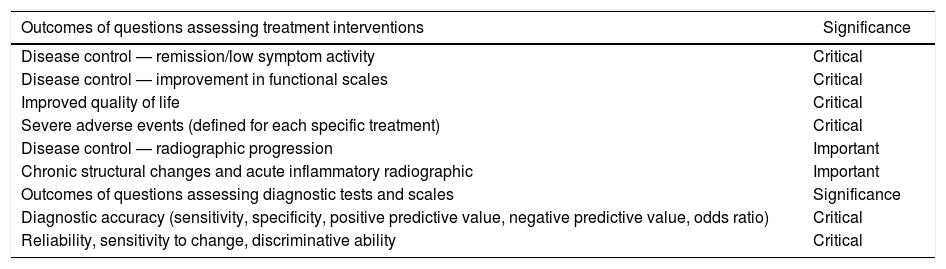

Drafting of clinical questions and definition of outcomesThe questions of the guidelines were designed via open consultation to all the GDT members and then prioritized by the GDT, pursuant to the Delphi methodology. A total of 2 rounds of virtual consultation were needed via e-mail to reach consensus (more than 80% of the GDT membership). The methodology suggested by the GRADEwg was used to grade the relevant outcomes for each question.13 The process was conducted virtually. The outcomes are shown in Table 1 and were considered critical and important for the total number of questions to be answered by the GDT, using in the definition the selection criteria of the evidence supporting each recommendation (Supplemental material [protocols per question available at: https://www.asoreuma.org]).

Grading of outcomes for questions on therapy and diagnosis.

| Outcomes of questions assessing treatment interventions | Significance |

|---|---|

| Disease control — remission/low symptom activity | Critical |

| Disease control — improvement in functional scales | Critical |

| Improved quality of life | Critical |

| Severe adverse events (defined for each specific treatment) | Critical |

| Disease control — radiographic progression | Important |

| Chronic structural changes and acute inflammatory radiographic | Important |

| Outcomes of questions assessing diagnostic tests and scales | Significance |

| Diagnostic accuracy (sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, odds ratio) | Critical |

| Reliability, sensitivity to change, discriminative ability | Critical |

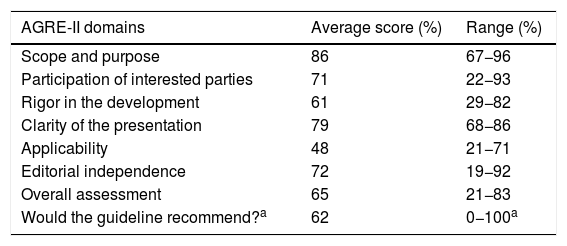

After defining the questions to be answered by the guidelines, a search was conducted to identify any CPG on pSpA, in order to assess the relevance of adapting and adopting some of their recommendations, according to the Adolopment strategy.17 A total of 10 CPG18–28 published over the past 5 years were identified as pre-established criterion, including the pSpA recommendation. These CPG were fully reviewed by 3 members of the GDT and an expert in methodology from Evidentias, using The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation Instrument (AGREE-II).29,30 The results of this assessment are shown in Table 2.

Assessment of the clinical practice guidelines in peripheral Spondyloarthritis according to AGREE-II.15,16

| AGRE-II domains | Average score (%) | Range (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Scope and purpose | 86 | 67−96 |

| Participation of interested parties | 71 | 22−93 |

| Rigor in the development | 61 | 29−82 |

| Clarity of the presentation | 79 | 68−86 |

| Applicability | 48 | 21−71 |

| Editorial independence | 72 | 19−92 |

| Overall assessment | 65 | 21−83 |

| Would the guideline recommend?a | 62 | 0−100a |

None of the CPGs approached all of the questions designed by the GDT to be answered as part of this guidelines. The CPGs that rigorously complied (based on the assessment by AGREE-II) were taken into consideration to adapt their recommendations for the questions for which no evidence was found to provide an answer.

Review of the evidence and development of the recommendationsThe Evidentias team conducted a systematic literature review following the international standards suggested by the Cochrane collaboration,31 to respond to each question and report on the effects (benefits and damages) of the interventions, the use of resources (profitability), values and preferences (relative importance of the results), potential impact on fairness, acceptability, and feasibility of implementing the potential recommendation.

Initially, a highly sensitive search strategy was developed to identify any publications associated with “Spondyloarthritis”. Based on this strategic definition of the condition, specific search strategies were developed for each question, considering the interventions and relevant comparators according to the structure «Patient, Intervention, Comparator and Outcome » (PICO) of each question. The necessary changes were introduced to the strategies defined (Ex. use of high-sensitivity filters for the identification of the relevant type of study) so that 3 complementary searches were conducted per each question: 1) one focusing on the identification of evidence to assess the effect of the intervention or diagnostic test; 2) another focused on the identification of cost studies and economic assessments to inform on the potential economic impact of the intervention; and 3) identification of studies on values and preferences of patients. The searches were designed by a bio-IT expert from Evidentias.

The searches were conducted using the OVID search engine, including PubMed/Medline, Embase, Epistemonikos and LILACs-SciELO. If the search failed to produce any relevant evidence to answer the question, a manual search was conducted reviewing references, accessing pages of scientific societies, and consultation with GDT experts.

The studies identified for each question were assessed by 2 clinical epidemiologists from Evidentias in terms of their methodological quality. The systematic reviews were assessed using the Assessing the Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews tool.32 The randomized clinical experiments were assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias,33 while the diagnostic studies and systematic reviews of diagnostic tests were assessed using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies tool.34 Cost studies were evaluated using the Drummond checklist, recommended for the appraisal of studies on economic analysis.35 The quality assessment of the studies on values and preferences was conducted pursuant to the GRADEwg recommendations for this type of evidence.36 The overall certainty of the evidence was assessed according to the GRAD37 approximation for developing evidence profiles and summary tables of findings that included the principal outcomes considered to be relevant to each question.

A protocol was designed for each question, including: the PICO structure, rating of outcomes, search strategy, description of the search results, a brief outline of the studies identified for each relevant aspect and its methodological quality, in addition to the outcomes summary table GRADE, as well as the “Evidence to decision” (EtD) framework suggested by GRADEwg to collect the necessary information on each aspect to consider, in order to produce the recommendations and opinions of the GDT on each particular aspect.15

The protocol for each question was reviewed by an expert rheumatologist of the GDT. Any comments and addenda suggested by the expert were taken into account to produce a new version of the protocol, which was finally submitted to all the GDT members for review. The articles sent by the experts as complementary information were assessed in terms of their methodological quality by the Evidentias team, and allocated to the columns “evidence” or “additional information” of the EtD framework.

The GDT members, representatives of patients and fairness experts were contacted by the CPG coordinators during the process of preparing the EtD, well in advance, in order to collect the relevant data to report on these 2 aspects.

At least 8 days prior to the meeting for the recommendations, all GDT members received all of the protocols developed for each question, via e-mail, encouraging them to read the information and prepare any additional information considered to be relevant and their opinion (vote) regarding each of the items under the EtD framework.

Two virtual meetings using Google Meet were held to generate the recommendations. In addition to the panel of experts, the representatives of patients, the representative of the society, the representatives of the Ministry of Health and Social protection, the IETS representatives and the experts in methodology participated in these meetings. The votes were casted using the Mentimeter® x electronic voting system. The recommendation was approved with 50% + 1 vote, of the total number of valid voters. The results of the ballot are available in the supplemental material (https://www.asoreuma.org). The meetings were video and audio recorded for future reference.

The final EtD was produced after the meeting, including the final opinions of the GDT, any amendments agreed and the recommendations submitted. The final protocols for each question were reviewed once again by the GDT in a virtual consult via e-mail (these protocols are part of the available supplemental material available at: https://www.asoreuma.org).

Interpretation of the recommendationsEach recommendation informs about the direction (in favor or against the intervention assessed and indicates the strength of a recommendation, which is expressed as strong—“the panel recommends…”—or conditional—“the panel suggests…”—). Occasionally, a strong recommendation is based on a low or very low certainty of the evidence. In such circumstances, the panel believes that additional enquiry on other aspects such as: economic impact, patient values, impact on fairness and acceptability of the intervention in the evaluation, contribute to the balance of the impact (beneficial or undesirable effects), and therefore alters the recommendations. The rationale of the considerations and the opinions of the panel support such recommendations.

Document reviewThe GDT conducted the activities leading to the inclusion of the various stakeholders and decision-makers: 1) dissemination of the scope, the objectives and the clinical questions included in the guidelines, via their publication in the Asoreuma webpage; 2) participation and ballot during the virtual meetings; 3) dissemination over the course of one month of the final CPG recommendations among the healthcare professionals and interested parties, via the Asoreuma webpage and social media posts; and 4) submission of the final document of the CPG for external peer review. The suggestion is to update this CPG every 2 years from the date of its publication, when there is evidence of any changes in the recommendations initially made. In the absence of any new evidence, the guidelines shall be reviewed every three years.

ResultsThe recommendations – based on each question asked – are as follows, and include the summary of the evidence.

Question 1In adult patients with pSpA should SNAID or conventional DMARDs (cDMARDs)38 be used as the first line of drug therapy, based on effectiveness (disease control, remission/low symptoms activity, improvement in functional scales) and safety (adverse events)?

Recommendation: in adult patients with pSpA the suggestion as first line therapy is the use of cDMARDs. Conditional recommendation in favor of cDMARDs intervention. Certainty of the evidence low ⊕⊕○○.

Good practice point: the panel considers that methotrexate or sulfasalazine may be used indistinctively.38 It is necessary to educate the patient about the treatment and its effects for improved treatment compliance and satisfaction.39,40

Rationale: upon consideration of the evidence on effectiveness, safety, use of resources, costs, value for patients and impact on fairness, the panel considers that the balance of the effects favors the intervention with cDMARDs, based on its potential effect on the improvement of patients and the fact that there are no differences in terms of adverse events as compared to placebo.38–40

Subgroup consideration: In patients with PsA, the suggestion is to use methotrexate as the first line therapy.38 Conditional recommendation in favor of methotrexate. Certainty of the evidence low ⊕⊕○○.

Question 2In adult patients with pSpA, should local or systemic glucocorticoids be used based on their effectiveness (disease control, remission/low symptom activity, improvement in function and quality of life scales, radiographic progression) and safety (adverse events)?

Recommendation: in patients with pSpA the recommendation is to avoid the use of systemic glucocorticoids. Strong recommendation against treatment. Certainty of the evidence low ⊕⊕○○.

Good practice point: prior to initiating glucocorticoid management in patients suspicious of pSpA, the recommendation is early referral to the rheumatologist to ensure management and diagnosis according to the highest quality standards.

Rationale: upon considering the evidence on effectiveness,41,42 safety,43–45 use of resources and costs,46,47 value for patients48 and potential impact on fairness, the panel considers that the balance of the effects is against the use of glucocorticoids. This is due to the known undesirable effects of the systemic use of these medications, and the very low evidence of any benefits. The panel considers that despite the poor evidence, glucocorticoids are frequently used in these patients; this recommendation reduces the variability of the therapeutic approach of pSpA, optimizes and rationalizes healthcare costs.

Subgroup consideration: in patients with PsA the recommendation is to avoid the use of systemic glucocorticoids. Strong recommendation against the treatment. Certainty of the evidence low ⊕⊕○○.

Rationale: the panel considers that in patients with PsA treated with systemic glucocorticoids, the discontinuation of the medication may lead to a flare of the psoriatic skin lesions.48

Question 3In adult patients with pSpA and cDMARDs failure, the first choice for biologic therapy is an TNFα, an anti-IL-17, an anti IL12–23, or JAK inhibitors, based on their effectiveness (disease control, remission/low symptom activity, improvement if function scales) and safety (adverse events)?

Recommendation: in patients with pSpA who failed therapy or are cDMARDs intolerant, the recommendation is to initiate treatment with an anti TNFα or an anti IL17A. Strong recommendation in favor. Certainty of the evidence moderate ⊕⊕⊕○.

Good practice point: during treatment with any of these biologic DMARDs (bDMARDS), strict patient follow-up is mandatory and regular assessment of the therapeutic response. Following a reasonable period of treatment, the medication should be discontinued to start therapy with a different class of molecule, in accordance with the individual patient characteristics.

Rationale: upon consideration of the evidence on effectiveness,49–59 safety,60,61 use of resources and costs,62–64 patient values and the potential impact on fairness, the panel considers that the balance of the effects favors the start of biologic therapy with an TNFα or an anti IL17A.

Subgroup considerations: in patients with psoriatic arthritis and treatment failure or cDMARDs intolerance, the recommendation is to initiate therapy with an anti TNFα or anti IL17A, anti-IL 12–23, anti PDE4 or a JAK inhibitor (tofacitinib). Strong recommendation in favor. Certainty of the evidence moderate ⊕⊕⊕○.

In patients with PsA and significant skin involvement who failed therapy of are intolerant to cDMARDs, the recommendation is to initiate treatment with an agent exhibiting a stronger effect on these manifestations such as ixekizumab or secukinumab.65,66 Strong recommendation in favor. Certainty of the evidence, moderate ⊕⊕⊕○.

Implementation considerations: among the various anti-IL17A, the use of secukinumab or ixekizumab is suggested, based on their higher probability of being cost-effective versus the various thresholds of willingness to pay in the countries in which they have been assessed, in contrast to other medications of the different subclasses considered.67,68

Question 4In adult patients with pSpA and failure to first line therapy with bDMARDs (anti TNFα, anti-IL-17, anti-IL 12-23) or JAK inhibitors, which DMARD should be used as the next treatment option, considering effectiveness (disease control, remission/low symptom activity, improvement if function scales) and safety (adverse events)?

Recommendation: in adult patients with pSpA and failure to first line therapy with bDMARDs, the suggestion is the use of another bDMARD as the next treatment option (whether with the same or with a different mechanism of action) or a JAK inhibitor. Conditional recommendation in favor of the intervention. Certainty of the evidence, moderate ⊕⊕⊕○.

Good practice point: the decision to change or discontinue therapy with the first bDMARD shall be made based on the objective analysis of the disease activity, using valid clinimetric tools. Expert consensus.

Rationale: upon consideration of the evidence on effectiveness and safety69–71 and use of resources and costs, the panel considered that the balance of effects is favorable for the continuation of treatment with another bDMARD. The panel acknowledges that the current evidence is only relevant for psoriatic arthritis, there is no evidence about all of the potential comparisons, and some are the result of a subgroup analysis with a small number of participants; in every case, the safety analyses of the treatments assessed are adequate.

Question 5In the treatment of adult patients with pSpA and associated uveitis as an extra-articular manifestation, cDMARDs should be used based on their effectiveness (disease control, remission/low symptom activity, improvement in functional scales( and safety (adverse events)?

Recommendation: in adult patients with pSpA and anterior uveitis (associated as an extra-articular manifestation) the suggestion is to use methotrexate or sulfasalazine with a view to reducing flares. Conditional recommendation in favor of the use of cDMARDs. Certainty of the evidence ⊕⊕○○.

Subgroup consideration: in adult patients with pSpA and anterior uveitis that fails to respond to management with immune-modulators, the suggestion is to use azathioprine to control the ocular inflammation. Conditional recommendation in favor of the intervention. Certainty of the evidence is low ⊕⊕○○.

Rationale: the panel considers that there is currently a lack of strong evidence about the use of immune-modulators in patients with SpA and anterior uveitis; however, the available evidence shows the potential effectiveness of methotrexate and of sulfasalazine to prevent acute manifestations of anterior uveitis and improve visual acuity, in addition to being safe in these patients. Upon consideration of the specific evidence on effectiveness and safety,72,73 and of the use of resources and costs,74 the patients’ values and preferences,75 and the potential impact on fairness, the panel considered that the balance of effects is in favor of cDMARDs treatment.

Question 6In the treatment of adult patients with pSpA and associated uveitis as an extra-articular manifestation, should bDMARDs (anti TNFα, anti-IL-17, anti IL 12–23) or JAK inhibitors be used, based on their effectiveness (disease control, remission/low symptom activity, improvement in functional scales) and safety (adverse events)?

Recommendation: in adult patients with pSpA and associated uveitis (as an extra-articular manifestation), with indication of bDMARDs, the use of an anti TNFα is suggested in order to reduce the rate of acute anterior uveitis. Conditional recommendation in favor of the intervention. Certainty of the evidence very low ⊕○○○.

Rationale: there is currently poor solid evidence to answer this question; the few experimental studies identified were placebo controlled and the most recent studies are observational or case series. Upon consideration of the evidence on effectiveness and safety, use of resources and costs, patient values and potential impact on fairness, the panel considered that the balance of the effects favors the intervention with anti TNFα (its potential benefits exceed the risks). Additionally, the panel considered that anti TNFα monotherapy does not show any clinically relevant differences in terms of undesirable effects (severe infections or hepatic events) when compared against combined methotrexate and anti TNFα therapy.76–83

Question 7In the treatment of adult patients with pSpA and associated inflammatory bowel disease, should cDMARDs be used in terms of their effectiveness (disease control, remission/low symptom activity, improvement in functional scales) and safety profile (adverse events)?

Recommendation: in patients with pSpA and associated inflammatory bowel disease, the suggestion is to initiate treatment with cDMARDs. Conditional recommendation in favor of the intervention. Certainty of the evidence very low ⊕○○○.

Rationale: the literature search analyzed failed to identify any study assessing the intervention of interest in these patients; hence a review of the Guidelines for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis of the American College of Rheumatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation published in 201884 was conducted and made recommendations for adult patients with active PsA and active inflammatory bowel disease, who were naive both to cDMARD and biologic therapy. The intent was to identify potential sources of information and assess the relevance of adopting some of their recommendations regarding this question. Upon considering the recommendations given in the guidelines and the supporting evidence, as well as the evidence on patient values and preferences, the panel decided to recommend by consensus the use cDMARDs, based on the fact that the balance of the effects favors the use of this intervention due to its potential moderate benefits, and the few undesirable effects observed with these therapies in multiple other treatment approaches (indirect evidence).

Question 8In the treatment of adult patients with pSpA and associated inflammatory bowel disease, should bDMARDs (anti TNFα, anti-IL-17, anti IL12–23) or JAK inhibitors be used, based on their effectiveness (disease control, remission/low symptom activity, improvement in functional scales) and safety profile (adverse events)?

Recommendation: in patients with pSpA and associated inflammatory bowel disease that do not respond to cDMARDs management, the recommendation is the use of an anti TNFα over treatment with other bDMARDs such as anti IL-17 or anti IL 12–23. Strong recommendation in favor of the use of anti TNFα. Certainty of the evidence: on anti-IL-17 moderate ⊕⊕⊕○; on anti-IL 12–23 very low ⊕○○○.

Good practice point: when choosing the anti TNFα in these patients, the suggestion is to prefer the use of monoclonal antibodies over soluble receptor bDMARDS.85–88 Certainty of the evidence: moderate ⊕⊕⊕○.

There is need to regularly monitor patients receiving this therapy to identify any adverse events in the long term.

Rationale: No studies were identified that assessed the intervention of interest in these patients; hence the recommendation made in this regard by the Guidelines for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis of the American College of Rheumatology and the National Psoriasis Foundation published in 2018 was reviewed.84 After assessing the additional evidence on the values and preferences of patients, the panel decided to adopt this recommendation by consensus, notwithstanding the lack of studies in the population of interest (pSpA and associated inflammatory bowel disease), the indirect evidence supports the effectiveness and safety of the biologic therapy with an antiTNFα in patients with Spondyloarthritis.

Question 9Is the use of clinimetric scales helpful to assess the activity of the disease in adult patients with pSpA (operating characteristics of the test): Disease Activity Score-28 vs. Disease Activity for Psoriatic Arthritis (DAPSA) vs Minimal Disease Activity?

Recommendation 9: in patients with PsA, the recommendation is to assess the activity of the disease using DAPSA based on its adequate ability to discriminate the activity of the disease. Conditional recommendation in favor. Certainty of the evidence, moderate ⊕⊕⊕○.

Good practice point: the suggestion is to complement the DAPSA assessment with the Minimal Disease Activity scale – if possible – keeping in mind that the evidence prevents the identification of superiority of one index over another, but they may complement each other when assessing different domains. Certainty of the evidence: moderate ⊕⊕⊕○.

Rationale: upon assessing the evidence with regards to precision and operating characteristics of the tests,89–91 patient values, use of resources and costs,92–96 the panel considered that the balance of the effects favors the use of the DAPSA clinimetric scale. However, this scale focuses mostly in peripheral joint disease and is able to accurately reflect any changes in this domain, but fails to measure other domains of the disease; this may neglect to document the disease activity (high disease activity on the skin).

Question 10In the treatment of adult patients with pSpA, is the use of combined methotrexate and bDMARDs therapy (anti TNFα, anti-IL-17, anti-IL 12–23) or JAK inhibitors more effective (disease control, remission/blow symptom activity, improvement in functional scales) and safer (adverse events) that the use of monotherapy with bDMARDs (anti TNFα, anti-IL-17, anti-IL 12–23) or JAK inhibitors?

Recommendation: in paients with PsA the combined use of methotrexate with bDMARDS (anti TNFα, anti-IL-17, anti-IL-12–23) is suggested. Conditional recommendation in favor of the intervention. Certainty of the evidence, low ⊕⊕○○.

Rationale: upon assessing the evidence of the effectiveness and safety of the patients and the use of resources and costs, the panel considered by consensus that the balance of the effects favors the combined therapy intervention. The use of methotrexate may be associated with higher retention of the biologic, and may additionally favor the dose optimization of the agent.97–100

DiscussionThis CPG provide the recommendations for the early diagnosis and treatment of adult patients with pSpA, and are addressed to the healthcare professionals involved with patient care, decision-makers, healthcare payers, and government agencies making health policies. These recommendations are intended to describe the treatment approach for typical patients and hence fail to anticipate every possible clinical scenario. Hence, the implementation of these recommendations should be individualized. This academic initiative is designed to reduce the variability in clinical practice and support decision-making for the management of patients with pSpA.

LimitationsThe evidence identified to answer most of the questions included in these guidelines is indirect, since no comparative studies were found among the assessment options studying patients with pSpA.

FinancingThe development of these CPG was possible thanks of the unrestricted support of the following institutions that jointly funded this effort: Abbvie, Amgen, Janssen, Novartis and Pfizer. The technical work of the process to develop these CPG was independently conducted by the GDT.

Conflict of interestsThe disclosures of each GDT member were submitted at the beginning of the development process of the CPG and before the start of the meetings to produce the recommendations by the rest of the participants. No conflict of interest was disclosed that prevented the participation or vote of any member.

The developer team of the guidelines wishes to express their gratitude to the representatives of patients María T. Castellanos and Julieth S. Buitrago (representative of the Anchylosing Spondylitis Foundation in Colombia), to Yuri Romero the anthropologist representing the civil society, to the representatives of the Ministry of health and Social Protection Gloria Villota, Rodrigo Restrepo, Nubia Bautista and Indira Caicedo, and to the IETS representatives Adriana Robayo, Kelly P. Estrada, Ani Cortez, Lorena del Pilar Mesa and Jeyson Javier Salamanca Rincón. Likewise, the GDT appreciates the participation, the methodological support, the advice and assistance of the representatives of Evidentias SAS, José R. Pieschacón MD, MsC, masters in clinical epidemiology, and María X. Rojas, nurse, masters in clinical epidemiology, Public Health specialist, Ph. D. in biomedical research with focus in economic evaluation.

Special appreciation to the external reviewers of the CPG, Mario H. Cardiel, MD, MSc., specialist in internal medicine and rheumatology from the Morelia SC Clinical Research Center in Michoacán, México; Research Unit Dr. Mario Alvizouri Muñoz of Dr. Miguel Silva General Hospital of the Health Secretariat of Michoacán State; Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México; and to Dr. Enrique R. Soriano MD, MSc, specialist in internal medicine and rheumatology, head of the Rheumatology Department of Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires and Director of the Master’s Program in Clinical Research of the same Hospital, former president of the Pan American League of rheumatology Associations and past president of the Argentinian Society of Rheumatology, member of the Board of Directors of Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis.

Please cite this article as: Saldarriaga-Rivera LM, Bautista-Molano W, Junca-Ramírez A, Fernández-Aldana AR, Fernández-Ávila DG, Jaimes DA, et al. Guía de práctica clínica 2021 para el diagnóstico, el tratamiento y el seguimiento de pacientes con espondiloartritis periférica. Asociación Colombiana de Reumatología. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2022;29:44–56.

This article is published simultaneously in Reumatología Clínica, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reuma.2021.09.002 and Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcreu.2021.07.005, with the consent of the authors and editors.