The kidney is one of the organs frequently affected in systemic lupus erythematosus (40–60%); the manifestations are variable, from a silent pattern to the irreversible impairment of renal function.

Materials and methodsDescriptive study with retrospective information in a group of patients under 18 years of age with a diagnosis of lupus nephritis, attended in two referral centres of the city of Medellin between 2008 and 2017. Clinical records of patients who met the inclusion criteria were reviewed.

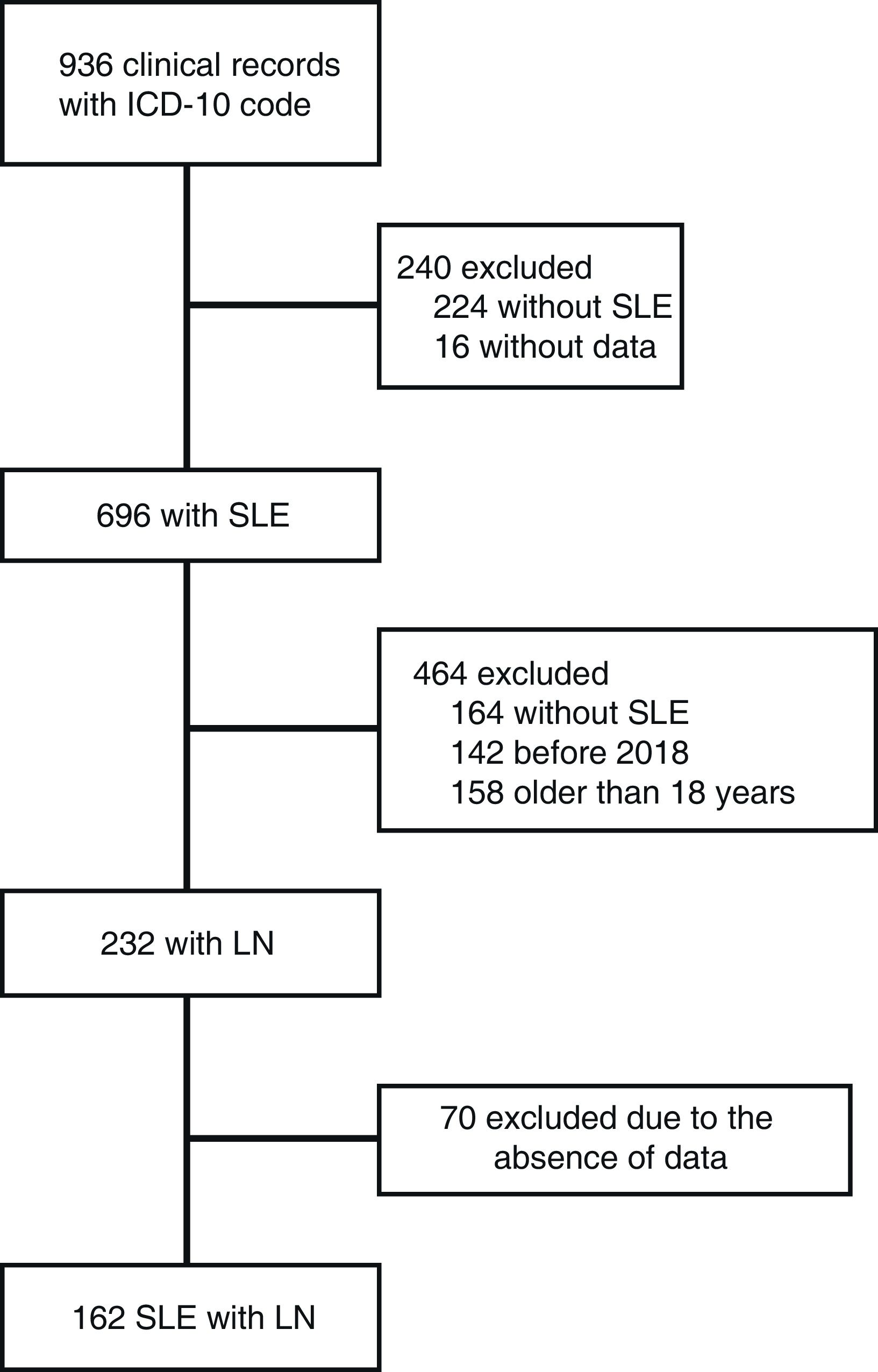

ResultsThe median age was 13 years, with predominance in females. The majority had renal involvement at the time of diagnosis of lupus. Histological class IV was the most frequent (48%). Age under 10 years, absence of response to induction therapy, and histological class IV, were related to the development of chronic kidney disease (>60 ml/min/1.73 m2).

ConclusionsRenal involvement was higher in this study. Age, class IV, and non-response to induction were associated with impaired renal function.

El riñón es uno de los órganos frecuentemente afectados en el lupus eritematoso sistémico (40–60%), con manifestaciones variables que van un patrón silente a la alteración irreversible de la función renal.

Materiales y métodosEstudio descriptivo con información retrospectiva en un grupo de pacientes menores de 18 años con diagnóstico de nefritis lúpica, atendidos en dos centros de referencia de la ciudad de Medellín entre los años 2008 y 2017. Se revisaron historias clínicas de los pacientes que cumplieron los criterios de inclusión.

ResultadosLa mediana de edad fue de 13 años, con predominio del sexo femenino. La mayoría presentaba afectación renal al momento del diagnóstico de lupus. La clase histológica IV fue la más frecuente (48%). Menores de 10 años, ausencia de respuesta a la terapia de inducción y clase histológica IV se relacionaron con el desarrollo de enfermedad renal crónica (>60 ml/min/1,73 m2).

ConclusionesLa afectación renal fue superior en este estudio. La edad, clase IV y la no respuesta a la inducción se asociaron con deterioro de la función renal.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multifactorial autoimmune disease characterized by systemic involvement, chronic progression, and variable severity. Among SLE patients, 15–20% are diagnosed before the age of 16, with an incidence of 0.28 to 0.9 cases per 100,000 children at risk per year, and a prevalence of 12 per 100,000. The disease predominantly affects females, with a female-to-male ratio of 8−13:1.1–4

Kidney involvement occurs in 40–60% of cases as the initial manifestation, with clinical characteristics that can vary. The incidence of end-stage chronic kidney disease in children is higher than in adults, with frequencies ranging from 16 to 45%, compared to 2.5% in adults.1,3,5–7

Lupus nephritis (LN) lesions are known to be dynamic, with frequent relapses and spontaneous transitions between different classes.1 The goals of lupus treatment include improving long-term survival, achieving remission or low disease activity, preventing multi-organ damage, minimizing drug toxicity, and enhancing the quality of life. Education of patients and their families on their role in the disease is also crucial. Patients with SLE and LN require multidisciplinary care tailored to disease activity, severity, and associated comorbidities.

The Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines recommend more aggressive treatment for proliferative histological classes (classes III and IV), with an induction therapy lasting at least 6 months using steroids and either cyclophosphamide or mycophenolate.8,9

Upon completion of induction therapy, subjects should be classified based on their 6-month response as: complete, partial, or no response, in accordance with KDIGO guidelines.8

In most recommendations, relapse during follow-up is typically defined by at least one of the following: persistence or recurrence of active urinary sediment, elevated creatinine levels, or an increase in 24-h proteinuria to more than 1 g if the response was complete, or more than 2 g if there was a partial response.8 There is currently no consensus on the definition of refractory disease.9

There is considerable variability in the clinical manifestations and histopathological aspects of LN, and its clinical course depends on various factors affecting the final prognosis. Early identification and treatment have improved overall and renal survival rates in SLE patients.10

Multiple risk factors are associated with the progression of LN to chronic kidney disease, with the cumulative risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) being as high as 33% at 5 years in individuals with diffuse proliferative glomerulonephritis. The development of ESRD also increases mortality risk, highlighting the importance of early detection. In patients with silent LN, renal survival rates reach 98% at 51 months, compared to clinical LN, which has survival rates of 60%–86% at 5 years.1,5,10–13

The objective of this study is to characterize subjects with childhood SLE who developed lupus nephritis and were treated at two high-complexity centers in Medellin, Colombia, and to conduct an exploratory analysis of variables related to renal prognosis.

MethodsStudy designThis descriptive study utilized a retrospective data collection approach. It included individuals under 18 years of age who were treated at Hospital Pablo Tobon Uribe and Hospital Universitario San Vicente Fundación in Medellín, Colombia, between January 2008 and December 2017. Inclusion was based on a diagnosis of the related conditions (M321, M328, and M329) as recorded in the clinical chart, according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition (ICD-10). Patients with incomplete medical records were excluded.

Variables examined included sociodemographic, clinical, paraclinical, and histopathological data at the time of lupus nephritis diagnosis, during the first relapse, and at the last recorded follow-up. Sociodemographic data collected comprised origin, race, social security status, sex, and age.

For subjects diagnosed with SLE before 2012, the 1997 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria were used, while those diagnosed after this date were assessed according to the 2012 SLICC criteria.14,15 Renal involvement was assessed using clinical and paraclinical parameters outlined in the KDIGO guidelines.8 Diagnosis of LN was confirmed by renal biopsy, and histopathological classification was based on the International Society of Nephrology and Renal Pathology Society (ISN/RPS) criteria from 2003.16

In individuals receiving induction therapy, responses were classified as complete, partial, or no response after 6 months, in line with KDIGO guidelines.8 Relapse during follow-up was defined by any of the following: increase or recurrence of active urinary sediment, elevated creatinine levels, or an increase in 24-h proteinuria to more than 1 g if there was a complete response, or more than 2 g if there was a partial response.8 Treatment resistance was identified as a lack of complete or partial response following the induction phase, and the treatments received by these patients were documented.9

Outcome variables evaluated at the final follow-up included chronic kidney disease, arterial hypertension (both in patients who were hypertensive at the time of SLE diagnosis and those who developed hypertension during follow-up), the need for renal replacement therapy (hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or kidney transplant), and death (due to SLE, infection, or other causes). Chronic kidney disease was defined according to the KDIGO guidelines.17

Statistical analysisFor qualitative variables, absolute frequencies and proportions were calculated. For quantitative variables, measures of central tendency (mean or median) and dispersion (standard deviation and interquartile range) were computed, depending on the distribution's normality.

An exploratory analysis of factors associated with renal prognosis was conducted using the Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, with a p-value <0.05 considered statistically significant. Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.

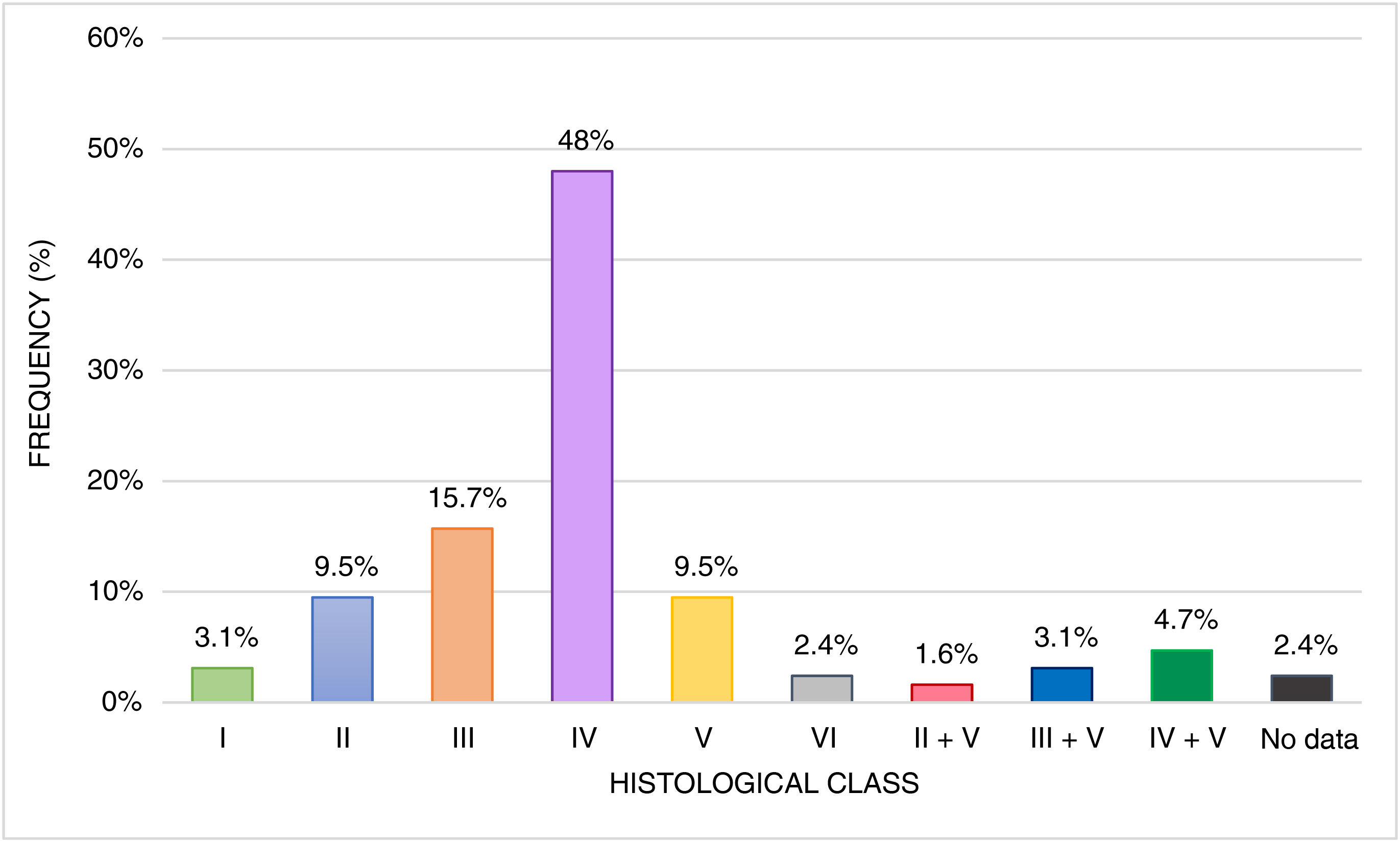

ResultsA total of 936 patient charts for individuals with SLE were reviewed, with 232 (58.5%) showing kidney involvement. Seventy patients were excluded due to incomplete data (see Fig. 1). Thus, 162 subjects met the inclusion criteria, with a median age at SLE diagnosis of 13 years (range: 2–17). Of these, 127 (78.4%) were female, resulting in a female-to-male ratio of 3.6:1. One hundred sixteen patients (71.6%) were from urban areas.

At the time of SLE diagnosis, the most common extrarenal clinical manifestations were mucocutaneous in 118 subjects (72.8%), joint symptoms in 108 (66.7%), and hematological issues in 102 (63%). Less frequent manifestations included serositis and neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Immunological findings included positive ANA in 144 individuals (88.9%), with a median titer of 1:640 (interquartile range [IQR]: 1:320–1:1280). Anti-dsDNA was positive in 102 patients (63%), with a median titer of 1:160 (IQR: 1:80–1:395) and a maximum value of 1:5120. Other markers included anti-Sm in 58 children (35.8%), anti-Ro in 48 (29.6%), anti-La in 20 (12.3%), anti-RNP in 61 (37.7%), and ANCA in 6 (3.7%). The antiphospholipid antibody profile was positive for lupus anticoagulant in 37 cases (22.8%), anticardiolipin IgM antibodies in 17 (10.5%), anticardiolipin IgG antibodies in 16 (9.9%), and anti-B2 glycoprotein 1 in 3 subjects (1.8%). C3 consumption was observed in 122 individuals (75.3%), with a median level of 40 mg% (IQR: 27–60.7), and hypocomplementemia for C4 was present in 114 (70.4%), with a median level of 4.65 mg% (IQR: 2.9–8.5). C3 complement levels were normal in 12 patients (7.4%) and C4 in 19 (11.7%). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) was elevated in 102 patients (63%).

At SLE onset, 114 subjects (70.4%) presented with kidney involvement, and 114 individuals (92%) after 2 years of follow-up. The maximum time between the diagnosis of SLE and the onset of lupus nephritis (LN) was 81.2 months.

Renal manifestations included nephritic syndrome in 9 subjects (5.6%), rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis in 13 (8%), nephrotic syndrome in 37 (22.8%), acute kidney injury in 45 (27.8%), arterial hypertension in 67 (41.4%), active sediment in 107 (66%), proteinuria in 144 (88.9%), and nephrotic-range proteinuria in 60 (37%). The median proteinuria value was 29.5 mg/m2/hour (IQR: 10.1–86), and the glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was 97 ml/min/1.73 m2 (IQR: 72.4–121). At the onset of LN, positive anti-dsDNA was found in 96 individuals (59.3%), with a median titer of 1:160 (IQR: 1:80−1:640). C3 and C4 consumption occurred in 113 (69.8%) and 110 patients (67.9%), respectively.

A total of 127 patients (78.4%) underwent renal biopsy. The most common histological class was class IV, observed in 61 cases (48%) (see Fig. 2). The median activity index was 5 (IQR: 2–9; range 0−17, n = 119), and the chronicity index was zero (IQR: 0−1; range 0−12, n = 119). Notable additional biopsy findings included crescents in 19 cases (11.7%), fibrinoid necrosis in 17 cases (10.5%), vasculitis in 6 cases (3.7%), thrombi in 5 cases (3.1%), and arteriolar fibrointimal hyperplasia in 2 cases (1.2%).

One hundred and twenty-one subjects received induction therapy: 93 were treated with cyclophosphamide (57.4%) and 28 with mycophenolate (17.3%). Sixty-eight patients received pulse methylprednisolone (42%).

In the cyclophosphamide group, 48 individuals (51.6%) achieved complete remission, 6 (6.4%) achieved partial remission, and 9 (9.7%) showed no response. In the mycophenolate group, 10 patients (35.7%) achieved complete remission, 5 (17.9%) achieved partial remission, and 2 (7.1%) showed no response. Seventeen subjects (10.5%) required a change in therapy during induction. Of these, 7 needed alternative therapies at onset. Immunoglobulin was administered to 2 patients—one for macrophage activation syndrome with pulmonary involvement and the other for hematological issues-. Additionally, 2 patients received plasmapheresis and rituximab for rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome versus thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). Another 2 subjects were treated with plasmapheresis plus immunoglobulin for refractory TMA and hip septic arthritis with acute kidney injury. The final patient received plasmapheresis for alveolar hemorrhage.

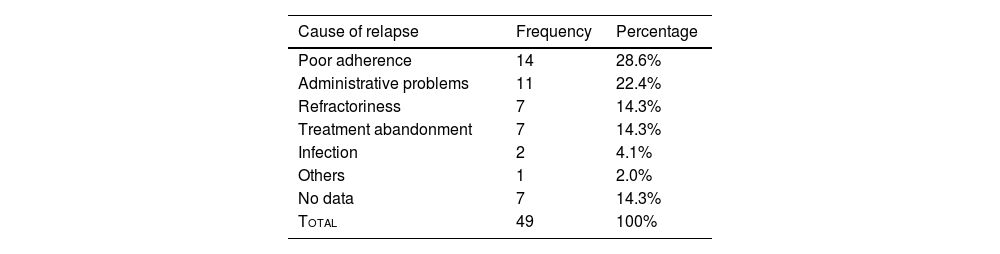

Renal relapseA total of 49 individuals (35%) experienced renal relapse, with poor adherence to treatment being the most frequent cause (n = 14; 28.6%). Other related causes are detailed in Table 1.

Among the manifestations at relapse, the most common was proteinuria, seen in 42 patients (85.7%). Nephrotic-range proteinuria was present in 21 cases (50%), active sediment in 35 (71.4%), acute kidney injury in 10 (20.4%), nephrotic syndrome in 6 (12.2%), and the need for hemodialysis in 3 cases (6.1%). Rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis occurred in 2 patients (4%), and nephritic syndrome in 1 patient (2%). Forty cases (81.6%) presented extrarenal symptoms at the time of relapse. Immunological findings included consumption of C4 in 35 patients (71.4%), with a median of 7.4 (IQR: 3.4–12), C3 hypocomplementemia in 33 subjects (67.3%), with a median of 57.4 (IQR: 36–88.5), and positive anti-dsDNA in 31 individuals (63.2%), with a median titer of 1:80 (IQR: 1:30−1:320, range 1:10−1:2560).

The median GFR was 110 ml/min/1.73 m2 (IQR: 85.7–139). Data from the last control were available for 89 patients.

Last check-upClinical data from the most recent follow-up were obtained for 140 patients, with a median follow-up duration of 31.13 months (IQR: 13.9–57.8). Of these, 89 subjects had their estimated creatinine clearance measured at this time. Among these, 53 patients (59.6%) showed improvement in GFR, 3 patients (5.6%) had stable GFR, and 33 patients (34.8%) experienced deterioration. Of the 66 individuals with histological class IV or combined classes IV + V, 8 had a GFR of less than 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 at the last follow-up (12.1%), and 7 were receiving renal replacement therapy at the last follow-up (10.6%).

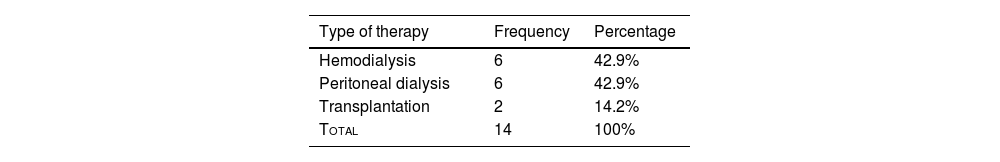

One hundred and two patients were at chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage 1 (81.6%), 43 had arterial hypertension (26.5%), and 14 were in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) (10%). The type of therapy administered is detailed in Table 2.

Forty-five subjects (32.1%) exhibited extrarenal symptoms. Regarding laboratory findings, 47 individuals had C3 consumption (33.5%), 54 C4 hypocomplementemia (38.5%), 45 positive anti-DNA antibodies (32.1%), 56 proteinuria (40%), 12 nephrotic-range proteinuria (21.4%), and 38 active sediment (27.1%). At the last follow-up, the number of patients and treatments received, respectively, were as follows: 6 rituximab (4.2%), 122 prednisone (87.1%), 64 mycophenolate (45.7%), 41 azathioprine (29.2%), and 1 tacrolimus (0.7%). Five patients died (3.5%), of which 3 deaths were related to SLE.

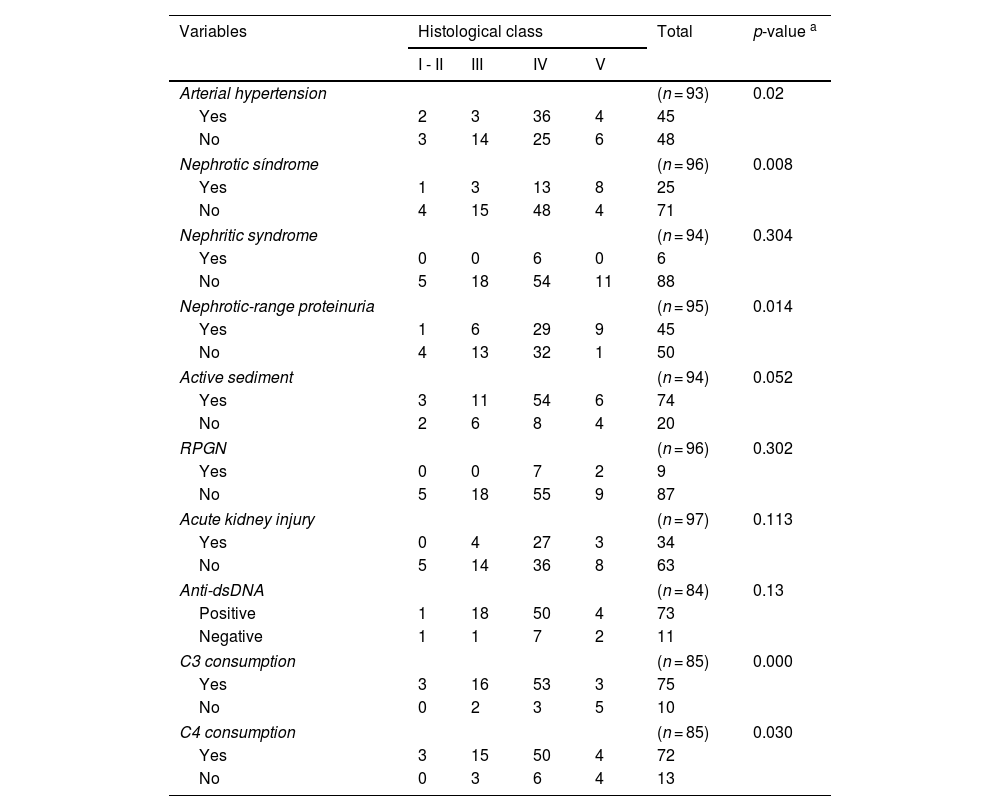

Bivariate analysisAn exploratory bivariate analysis was performed on renal clinical manifestations, immunological data, and histological classes, revealing significant differences for arterial hypertension, nephrotic syndrome, nephrotic-range proteinuria, and complement consumption (see Table 3).

Bivariate analysis of clinical manifestations, immunological data, and histological class.

| Variables | Histological class | Total | p-value a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I - II | III | IV | V | |||

| Arterial hypertension | (n = 93) | 0.02 | ||||

| Yes | 2 | 3 | 36 | 4 | 45 | |

| No | 3 | 14 | 25 | 6 | 48 | |

| Nephrotic síndrome | (n = 96) | 0.008 | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 3 | 13 | 8 | 25 | |

| No | 4 | 15 | 48 | 4 | 71 | |

| Nephritic syndrome | (n = 94) | 0.304 | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 6 | |

| No | 5 | 18 | 54 | 11 | 88 | |

| Nephrotic-range proteinuria | (n = 95) | 0.014 | ||||

| Yes | 1 | 6 | 29 | 9 | 45 | |

| No | 4 | 13 | 32 | 1 | 50 | |

| Active sediment | (n = 94) | 0.052 | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 11 | 54 | 6 | 74 | |

| No | 2 | 6 | 8 | 4 | 20 | |

| RPGN | (n = 96) | 0.302 | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 9 | |

| No | 5 | 18 | 55 | 9 | 87 | |

| Acute kidney injury | (n = 97) | 0.113 | ||||

| Yes | 0 | 4 | 27 | 3 | 34 | |

| No | 5 | 14 | 36 | 8 | 63 | |

| Anti-dsDNA | (n = 84) | 0.13 | ||||

| Positive | 1 | 18 | 50 | 4 | 73 | |

| Negative | 1 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 11 | |

| C3 consumption | (n = 85) | 0.000 | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 16 | 53 | 3 | 75 | |

| No | 0 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 10 | |

| C4 consumption | (n = 85) | 0.030 | ||||

| Yes | 3 | 15 | 50 | 4 | 72 | |

| No | 0 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 13 | |

RPGN: Rapidly Progressive Glomerulonephritis.

In the analysis of the last glomerular filtration rate about additional data from the baseline renal biopsy, a significant difference was found for an activity index greater than or equal to 7 (p = 0.01).

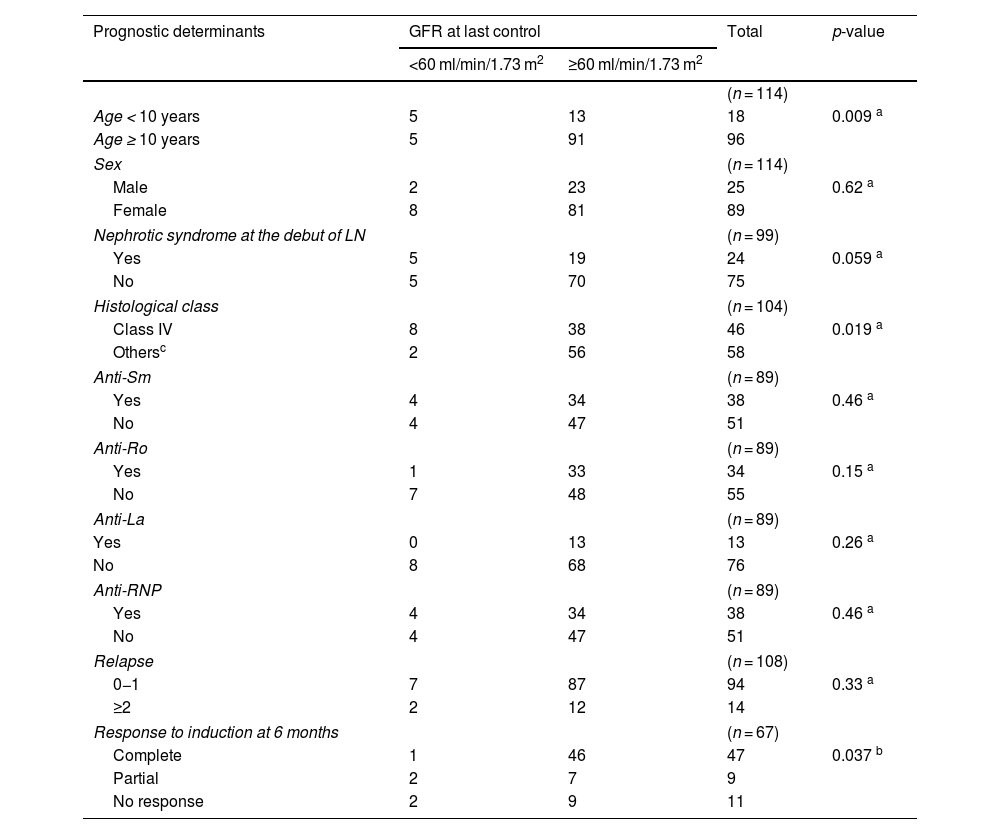

Among the prognostic factors and the stage of chronic kidney disease at the last follow-up, statistical significance was observed with the age at onset of SLE being under 10 years, histological class IV, and the absence of a complete response to induction therapy (see Table 4).

Bivariate analysis between prognostic determinants and glomerular filtration rate at the last follow-up.

| Prognostic determinants | GFR at last control | Total | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 | ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2 | |||

| (n = 114) | ||||

| Age < 10 years | 5 | 13 | 18 | 0.009 a |

| Age ≥ 10 years | 5 | 91 | 96 | |

| Sex | (n = 114) | |||

| Male | 2 | 23 | 25 | 0.62 a |

| Female | 8 | 81 | 89 | |

| Nephrotic syndrome at the debut of LN | (n = 99) | |||

| Yes | 5 | 19 | 24 | 0.059 a |

| No | 5 | 70 | 75 | |

| Histological class | (n = 104) | |||

| Class IV | 8 | 38 | 46 | 0.019 a |

| Othersc | 2 | 56 | 58 | |

| Anti-Sm | (n = 89) | |||

| Yes | 4 | 34 | 38 | 0.46 a |

| No | 4 | 47 | 51 | |

| Anti-Ro | (n = 89) | |||

| Yes | 1 | 33 | 34 | 0.15 a |

| No | 7 | 48 | 55 | |

| Anti-La | (n = 89) | |||

| Yes | 0 | 13 | 13 | 0.26 a |

| No | 8 | 68 | 76 | |

| Anti-RNP | (n = 89) | |||

| Yes | 4 | 34 | 38 | 0.46 a |

| No | 4 | 47 | 51 | |

| Relapse | (n = 108) | |||

| 0−1 | 7 | 87 | 94 | 0.33 a |

| ≥2 | 2 | 12 | 14 | |

| Response to induction at 6 months | (n = 67) | |||

| Complete | 1 | 46 | 47 | 0.037 b |

| Partial | 2 | 7 | 9 | |

| No response | 2 | 9 | 11 | |

GFR: Glomerular Filtration Rate; LN: Lupus Nephritis.

In the exploratory analysis of prognostic factors and the requirement for renal replacement therapy at the last follow-up, no statistically significant differences were found for histological class IV (n = 120; p = 0.29), anemia at the onset of LN (n = 123; p = 0.57), persistent hypertension (n = 79; p = 0.24), or nephrotic-range proteinuria (n = 119; p = 0.125).

Among the 31 subjects who experienced a relapse, there were no significant differences between this outcome and histological class (p = 0.056), additional biopsy findings (thrombi - p = 0.96; crescents - p = 0.28; fibrinoid necrosis - p = 0.81; vasculitis - p = 0.84; and arteriolar fibrointimal hyperplasia - p = 0.80), or the need for renal replacement therapy (p = 0.68).

DiscussionThis series represents the largest cohort of pediatric patients with SLE reported in Latin America and the third largest globally.18,19 Among the total number of pediatric SLE patients, 58.5% exhibited renal involvement, with a predominance in females and adolescents, consistent with findings from other studies, such as those by Caggiani et al. and Ferreira et al., both of which are Latin American, and with only one case diagnosed at 2 years old.20–23

Mucocutaneous, joint, and hematological involvement were the most common extrarenal manifestations. This finding is similar to that reported by Caggiani in Uruguay in 2016. However, it contrasts with Ferreira’s study, which found hematological and neurological manifestations to be more prevalent; also, Beltrán et al.'s study in Colombia reported a predominance of dermatological and hematological manifestations.20–22

The immunological findings at SLE diagnosis varied compared to the reviewed series, showing a lower percentage of positivity, particularly for anti-dsDNA, anti-Sm, and C3 consumption, due to incomplete documentation in medical records. Nonetheless, these findings are somewhat similar to those reported by Ferreira in Venezuela.4,22,24

Renal involvement at the onset of SLE occurred in 70.4% of patients, differing from the frequency of 50% reported in lupus review articles, yet comparable to another national series published in 2004.4,21,23,25 The literature indicates that some degree of renal involvement is present in up to 80% of patients within the first year and 90% within 2 years, consistent with the findings of this series.26,27

The most frequent renal manifestations were proteinuria, active sediment, and arterial hypertension. These findings align with those reported by Youssef et al. in Egypt in 2015 but differ from the Latin American series by Beltrán and Ferreira, which reported a greater frequency of variations in glomerular filtration rate, and from Szymanik’s study in Poland, which highlighted nephrotic syndrome. The presence of positive anti-dsDNA and complement consumption was alike to the results in the Venezuelan series.4,21–23 The most frequent histological class in this study was class IV (48%), consistent with global literature, although exceptions were noted in the series from Uruguay and Puerto Rico, where class III (60%) and class II (41%) predominated, respectively.19,20,26,28

Previous series do not report additional findings from renal biopsies. Caggiani’s study described the presence of crescents in 25% of patients, with one case showing rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis and 80% crescents, 65% tubulo-interstitial involvement, and one case with thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). This study had limited data, noting crescents in 11.7%, with no information on tubulo-interstitial involvement and three cases of TMA.20

Cyclophosphamide was the most used medication for the induction phase in this study, consistent with other national and Asian series.19,21,24,29 The complete response rate was 47.9% (cyclophosphamide: n = 48; mycophenolate: n = 10), which is lower compared to other studies reporting around 87%.19

However, it is important to note that in this series, more than half of the patients faced administrative difficulties with the timely delivery of therapy. Other treatments at onset included plasmapheresis, immunoglobulin, and rituximab, used in 5.8% of patients, related to clinical severity and lower than the rate reported by Bogdanović.27

Relapses occurred at a higher percentage compared to Hari's series (19%) in India, although Jebali et al. in Tunisia report a 65.7% relapse rate.2,30 The primary causes of relapse in this study were treatment abandonment or poor adherence, which is consistent with the findings of Caggiani and the Tunisian series mentioned above.20 Notably, a quarter of the subjects in this study experienced administrative issues, a factor not described by other groups.

The follow-up period in this study was shorter than that in other series.20,27,28,31 Progression to end-stage chronic kidney disease occurred in 10% of patients (14 individuals). This percentage varies in the literature, ranging from 6.8% to 36.3% (with the higher end reported by Beltrán et al., who also studied a Colombian population). Despite the shorter follow-up period, the frequency of progression in this study was higher than in most studies with longer follow-ups, suggesting that the population studied might be at greater risk for permanent kidney damage. Further research with different study designs would be needed to explore this result.18,21,27–29,31 Arterial hypertension at the end of the follow-up was 26.5%, which is higher than reported by Melvin and Bogdanović, but lower than another local series.21,27,28

The two previously published national series reported a higher mortality rate than this study. However, the causes of death were similar, with the majority attributed to disease activity followed by infectious complications, consistent with Caggiani et al.20,27 Ferreira in Venezuela and Hari in India reported higher death rates (19% and 23%, respectively), with infections as the main cause, followed by complications associated with chronic kidney disease.2,22

In the exploratory analysis, a relationship was found between clinical manifestations (such as arterial hypertension, nephrotic syndrome, and nephrotic-range proteinuria) and immunological findings (such as complement consumption and positive anti-dsDNA) with histological class IV, similar to most literature reports.18,20,24,29,31 Despite a high frequency of acute kidney injury and nephritic syndrome in this histological class, this was not statistically significant compared to studies by Hari, Caggiani, and Emre.2,20,31 Notably, Jebali et al. found no significant difference between clinical and immunological manifestations and histological classes.30

Austin et al. found a relationship between an activity index ≥7 and deterioration of renal function (GFR < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2), which aligns with current findings. However, the chronicity index differed, likely due to fewer chronicity findings in the biopsies of this study.32 Other biopsy findings, such as crescents and fibrinoid necrosis, were explored as markers of poor renal outcomes but were not statistically significant.13,32–34

Factors related to worse clinical outcomes, specifically chronic kidney disease (<60 ml/min/1.73 m2), age of SLE onset <10 years, histological class IV, and lack of response to induction therapy, which are similar to findings by Caggiani, Emre, and Srivastava.20,31,35 Factors from other studies such as race, complement consumption, arterial hypertension, serum creatinine levels, and need for renal replacement therapy at onset and relapses related to ESRD were not significant in this study,6,9,20,28,31,35,36 corroborating Hari’s 2009 findings.2

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective nature, which affects the reliability of the information found in the records.

ConclusionsThis study presents the demographic, clinical, paraclinical, and histopathological profiles of pediatric lupus nephritis patients treated in Medellin, Colombia. It represents the largest characterization of this condition in the country and Latin America to date.

The demographic features are similar to those reported globally, except for race, which was not assessed. The percentage of renal involvement was higher than in most series. Histopathological class IV was the most common and correlated with clinical and immunological data described in the literature. This series also found a higher frequency of chronic kidney disease compared to many reviewed studies.

Significant differences were observed in renal function deterioration related to age, histological class, and lack of response to induction therapy. Further studies with prospective designs are needed to explore these results and investigate other findings described in the literature.

Conflict of interestNo conflicts of interest were reported by the authors.