Clinical practice guideline 2022 for the early detection, diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of patients with rheumatoid arthritis developed by the rheumatoid arthritis study group of the Colombian Association of Rheumatology. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common autoimmune disease in adults. Worldwide, RA has a prevalence of 0.5%–1%, with an age-standardised prevalence rate of 246.6 per 100,000 population, being more common in women than in men and with peak presentation between the ages of 60 and 64 years. The disease is characterised by joint pain and inflammation and in some cases can cause extra-articular manifestations such as dry syndrome, vasculitis, pericarditis, pleuritis, scleritis, among others. RA causes great morbidity, impairment of quality of life, severe disability, high direct and indirect costs to health systems, disability, and absenteeism from work. This guideline was developed for rheumatologists, primary care physicians, specialists in related areas, and other actors in the system with the aim of providing the most relevant information on the early detection of the disease, and its correct diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up.

Guía de práctica clínica 2022 para la detección temprana, el diagnóstico, el tratamiento y el seguimiento de los pacientes con artritis reumatoide (AR) desarrollada por el grupo de estudio de artritis reumatoide de la Asociación Colombiana de Reumatología. La AR es la enfermedad autoinmune más frecuente en adultos. A nivel mundial, la AR tiene una prevalencia de entre el 0,5 y el 1%, con una tasa de prevalencia estandarizada por edad de 246,6 por cada 100.000 habitantes, siendo más frecuente en mujeres que en varones y con un pico de presentación entre los 60 y los 64 años. Esta enfermedad se caracteriza por dolor e inflamación articular, y en algunos casos puede causar manifestaciones extraarticulares como síndrome seco, vasculitis, pericarditis, pleuritis y escleritis, entre otras. La AR produce gran morbilidad, afectación de la calidad de vida, discapacidad grave, altos costos directos e indirectos para los sistemas de salud, incapacidad y ausentismo laboral. Esta guía ha sido desarrollada para reumatólogos, médicos de atención primaria, especialistas de áreas afines y otros actores del sistema con el objetivo de brindar la información más relevante relacionada con la detección temprana de la enfermedad, así como su correcto diagnóstico, tratamiento y seguimiento.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common autoimmune disease in adults. On a global scale, it has a prevalence of between 0.5 and 1%, with an age-standardized prevalence rate of 246.6 per 100,000 inhabitants; it is more common in females than males, while its peak presentation is between 60 and 64 years.1,2 In Colombia, its estimated prevalence ranges between 0.52 and 1.49%, representing the most common autoimmune disease with inflammatory joint involvement in the country, with a female: male ratio of 4.2:1 and a higher prevalence in the age range of 70–74 years.3,4

This disease is characterized by joint pain and inflammation, and in some cases, it can present extraarticular manifestations such as sicca syndrome, vasculitis, pericarditis, pleuritic, and scleritis, among others. It entails great morbidity, impact on quality of life, severe inability, high direct and indirect costs for health systems, disability, and work absenteeism.5 Patient management includes non-pharmacological and pharmacological interventions to improve quality of life through the reduction of symptoms and the prevention or reduction of joint damage and complications of the disease.6

Scientific evidence has shown that disease progression can be delayed with timely and appropriate treatment. In recent years, new therapeutic strategies have appeared that positively impact patients’ quality of life and improve their functionality.5 In this context, the Colombian Association of Rheumatology (ASOREUMA) developed this clinical practice guideline (CPG) to provide evidence-based recommendations regarding early diagnosis, comprehensive treatment (pharmacological and non-pharmacological), and follow-up of adults with a diagnosis or suspected diagnosis of RA, regardless of the time of evolution and the clinical disease status.

This guideline is primarily aimed at all health professionals involved in the care of patients with RA at different levels: general practitioners, specialists, and other health professionals. Likewise, it can constitute a support tool for the different actors in the health system in Colombia, including decision-makers.

MethodsThe development of this CPG included the participation of clinical experts in rheumatology, patients with RA, and a methodological technical team from the EpiThink consultant (the list of participants and declaration of interests can be checked in Supplementary material 1). The recommendations presented here were constructed following the Grade-Adolopment methodology7 (methodological details are found in Supplementary material 2). In general, the development group formulated the clinical questions and outcomes of interest for the CPG approach (Supplementary material 3), carried out a systematic search for guidelines, and performed a quality assessment using the AGREE II instrument.8 Due to its high quality, adaptability, and convenience, the Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Spanish Society of Rheumatology9 was chosen as a source for updating the literature searches.

Once the matching recommendations for each posed question were identified, the original strategies were reproduced in the Medline (via PubMed), Embase (Elsevier), and Cochrane databases. Additionally, the LILACS database was used to include Latin American evidence. To search the literature for questions not posed in the source guideline, strategies were created that combined free and controlled language terms according to the Thesaurus corresponding to each database (the strategies and search results can be consulted in Supplementary material 4). The selection of the identified references was conducted by two reviewers who independently evaluated the documents under the eligibility criteria, initially screening the references by title and abstract, and then reviewing the full text of the potentially relevant articles (see Prisma in Supplementary material 5). A quality assessment was carried out on selected articles and the evidence was summarized in tables following the GRADE methodology (the summary of evidence is found in Supplementary material 6).

Each expert in the development group, constituted of 9 specialists in rheumatology, reviewed the original recommendations of the source guideline, along with the new evidence resulting from the update, and defined at their discretion whether the original recommendation should be adopted or adapted. Subsequently, in multiple discussion sessions, the construction of the recommendations was performed. Finally, in a session with 23 specialists in rheumatology and 2 representatives of patients with RA, the posed questions, the supporting evidence for each topic, and the recommendations formulated for each clinical issue were presented. Panel participants voted on each of the recommendations and discussed the risk-benefit balance, feasibility of implementation, and possible impact on resource use. A preliminary version of the guideline manuscript was reviewed and adjusted by all members of the development group and was subsequently sent for external peer review.

All aspects covered in this guideline are subject to periodic review as warranted by the evolution of medical knowledge, technology, and practice (see the updating process in Supplementary material 2).

Key definitions and general principlesThe recommendations presented in this guideline are indicative but do not constitute a rigid guide for the care of patients with RA. Clinicians must make individualized decisions, ideally through a shared process that considers patient values and preferences. Therapeutic decisions may be limited by the realities of a specific clinical setting and resource availability, among others.

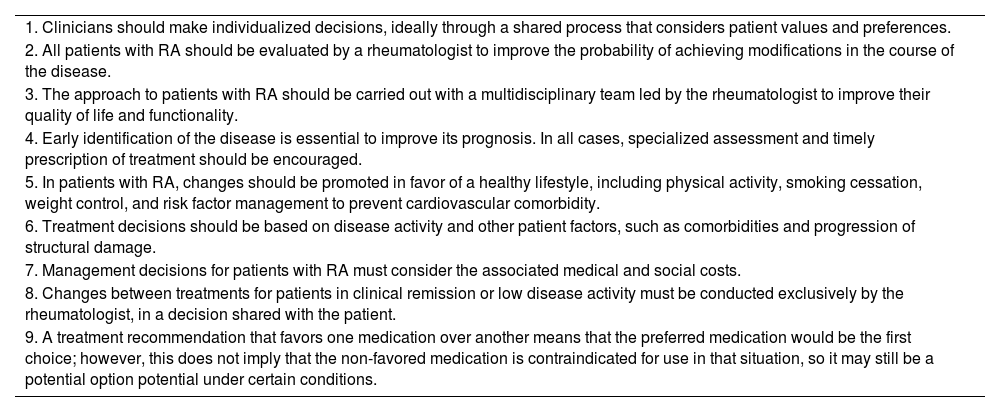

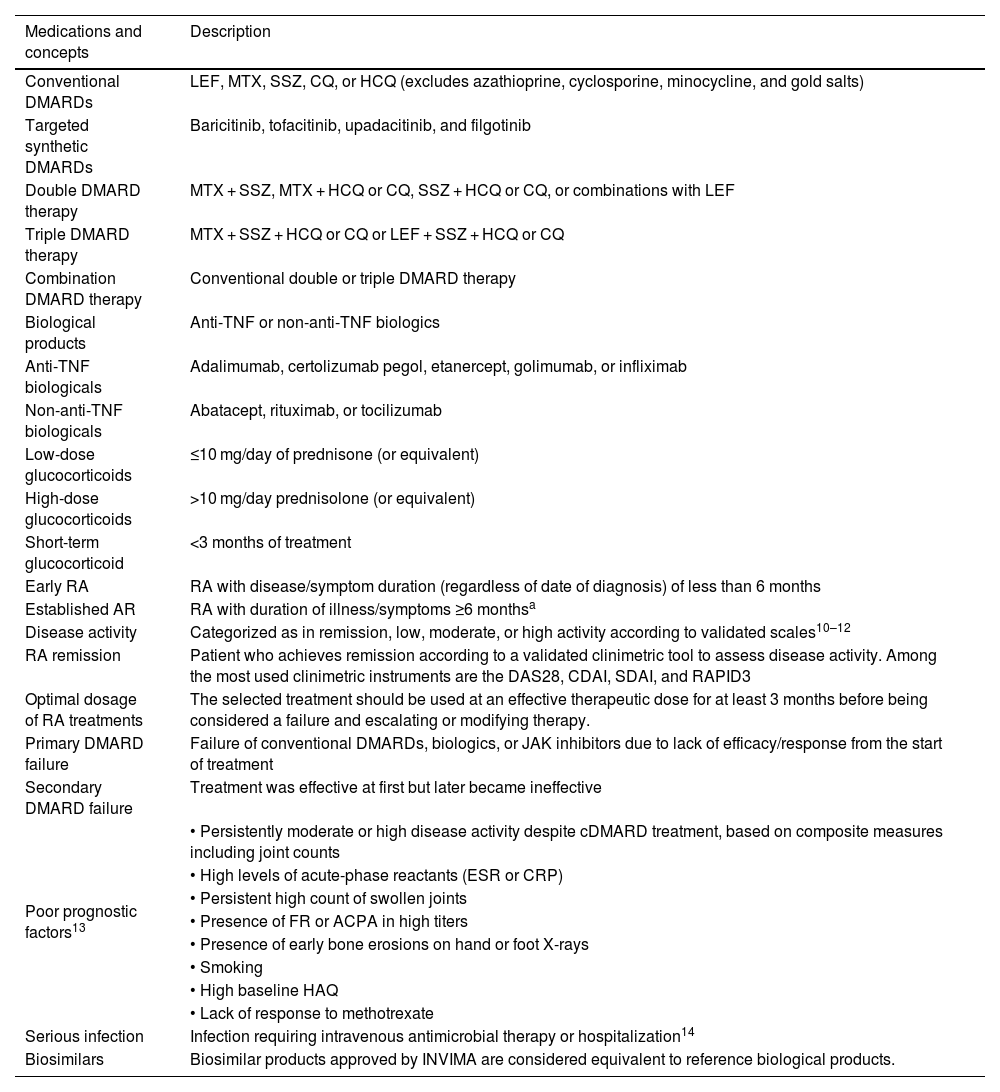

Tables 1 and 2 outline the key definitions and general principles applicable to this guideline.

General principles in the management of patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

| 1. Clinicians should make individualized decisions, ideally through a shared process that considers patient values and preferences. |

| 2. All patients with RA should be evaluated by a rheumatologist to improve the probability of achieving modifications in the course of the disease. |

| 3. The approach to patients with RA should be carried out with a multidisciplinary team led by the rheumatologist to improve their quality of life and functionality. |

| 4. Early identification of the disease is essential to improve its prognosis. In all cases, specialized assessment and timely prescription of treatment should be encouraged. |

| 5. In patients with RA, changes should be promoted in favor of a healthy lifestyle, including physical activity, smoking cessation, weight control, and risk factor management to prevent cardiovascular comorbidity. |

| 6. Treatment decisions should be based on disease activity and other patient factors, such as comorbidities and progression of structural damage. |

| 7. Management decisions for patients with RA must consider the associated medical and social costs. |

| 8. Changes between treatments for patients in clinical remission or low disease activity must be conducted exclusively by the rheumatologist, in a decision shared with the patient. |

| 9. A treatment recommendation that favors one medication over another means that the preferred medication would be the first choice; however, this does not imply that the non-favored medication is contraindicated for use in that situation, so it may still be a potential option potential under certain conditions. |

RA: rheumatoid arthritis.

Definitions in the context of rheumatoid arthritis.

| Medications and concepts | Description |

|---|---|

| Conventional DMARDs | LEF, MTX, SSZ, CQ, or HCQ (excludes azathioprine, cyclosporine, minocycline, and gold salts) |

| Targeted synthetic DMARDs | Baricitinib, tofacitinib, upadacitinib, and filgotinib |

| Double DMARD therapy | MTX + SSZ, MTX + HCQ or CQ, SSZ + HCQ or CQ, or combinations with LEF |

| Triple DMARD therapy | MTX + SSZ + HCQ or CQ or LEF + SSZ + HCQ or CQ |

| Combination DMARD therapy | Conventional double or triple DMARD therapy |

| Biological products | Anti-TNF or non-anti-TNF biologics |

| Anti-TNF biologicals | Adalimumab, certolizumab pegol, etanercept, golimumab, or infliximab |

| Non-anti-TNF biologicals | Abatacept, rituximab, or tocilizumab |

| Low-dose glucocorticoids | ≤10 mg/day of prednisone (or equivalent) |

| High-dose glucocorticoids | >10 mg/day prednisolone (or equivalent) |

| Short-term glucocorticoid | <3 months of treatment |

| Early RA | RA with disease/symptom duration (regardless of date of diagnosis) of less than 6 months |

| Established AR | RA with duration of illness/symptoms ≥6 monthsa |

| Disease activity | Categorized as in remission, low, moderate, or high activity according to validated scales10–12 |

| RA remission | Patient who achieves remission according to a validated clinimetric tool to assess disease activity. Among the most used clinimetric instruments are the DAS28, CDAI, SDAI, and RAPID3 |

| Optimal dosage of RA treatments | The selected treatment should be used at an effective therapeutic dose for at least 3 months before being considered a failure and escalating or modifying therapy. |

| Primary DMARD failure | Failure of conventional DMARDs, biologics, or JAK inhibitors due to lack of efficacy/response from the start of treatment |

| Secondary DMARD failure | Treatment was effective at first but later became ineffective |

| Poor prognostic factors13 | • Persistently moderate or high disease activity despite cDMARD treatment, based on composite measures including joint counts |

| • High levels of acute-phase reactants (ESR or CRP) | |

| • Persistent high count of swollen joints | |

| • Presence of FR or ACPA in high titers | |

| • Presence of early bone erosions on hand or foot X-rays | |

| • Smoking | |

| • High baseline HAQ | |

| • Lack of response to methotrexate | |

| Serious infection | Infection requiring intravenous antimicrobial therapy or hospitalization14 |

| Biosimilars | Biosimilar products approved by INVIMA are considered equivalent to reference biological products. |

ACPA: anticitrullinated protein antibodies; anti-TNF: tumor necrosis factor inhibitor: RA: rheumatoid arthritis; CDAI: Clinical Disease Activity Index; CQ: chloroquine; DAS28: Disease Activity Score 28; DMARD: disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; cDMARDS: conventional synthetic DMARD; RF: rheumatoid factor; HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; HCQ: hydroxychloroquine; JAK: Janus kinases; LEF: leflunomide; MTX: methotrexate; CRP: C-reactive protein; RAPID3: Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3; SDAI: Simplified Disease Activity Index; SSZ: sulfasalazine; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

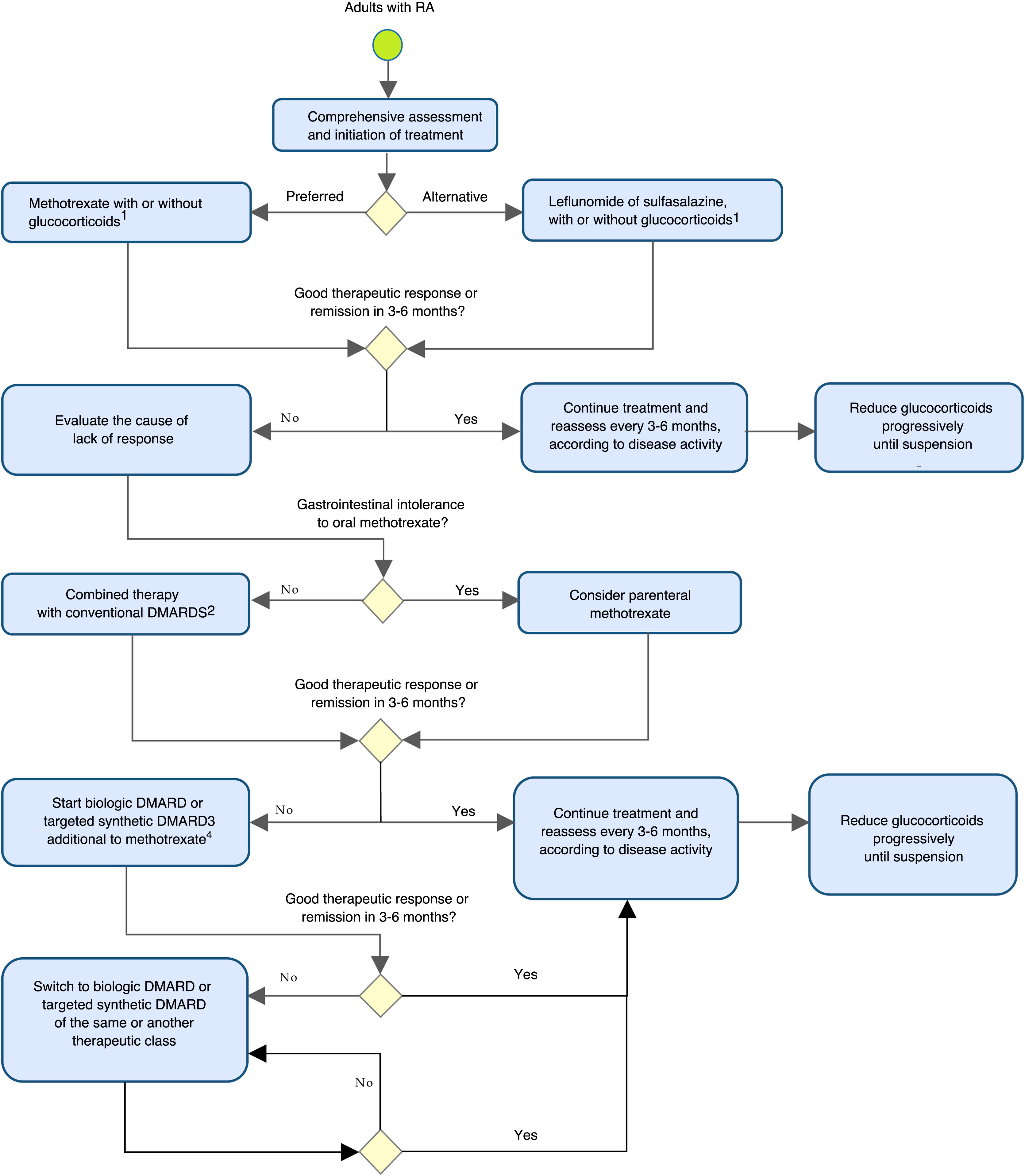

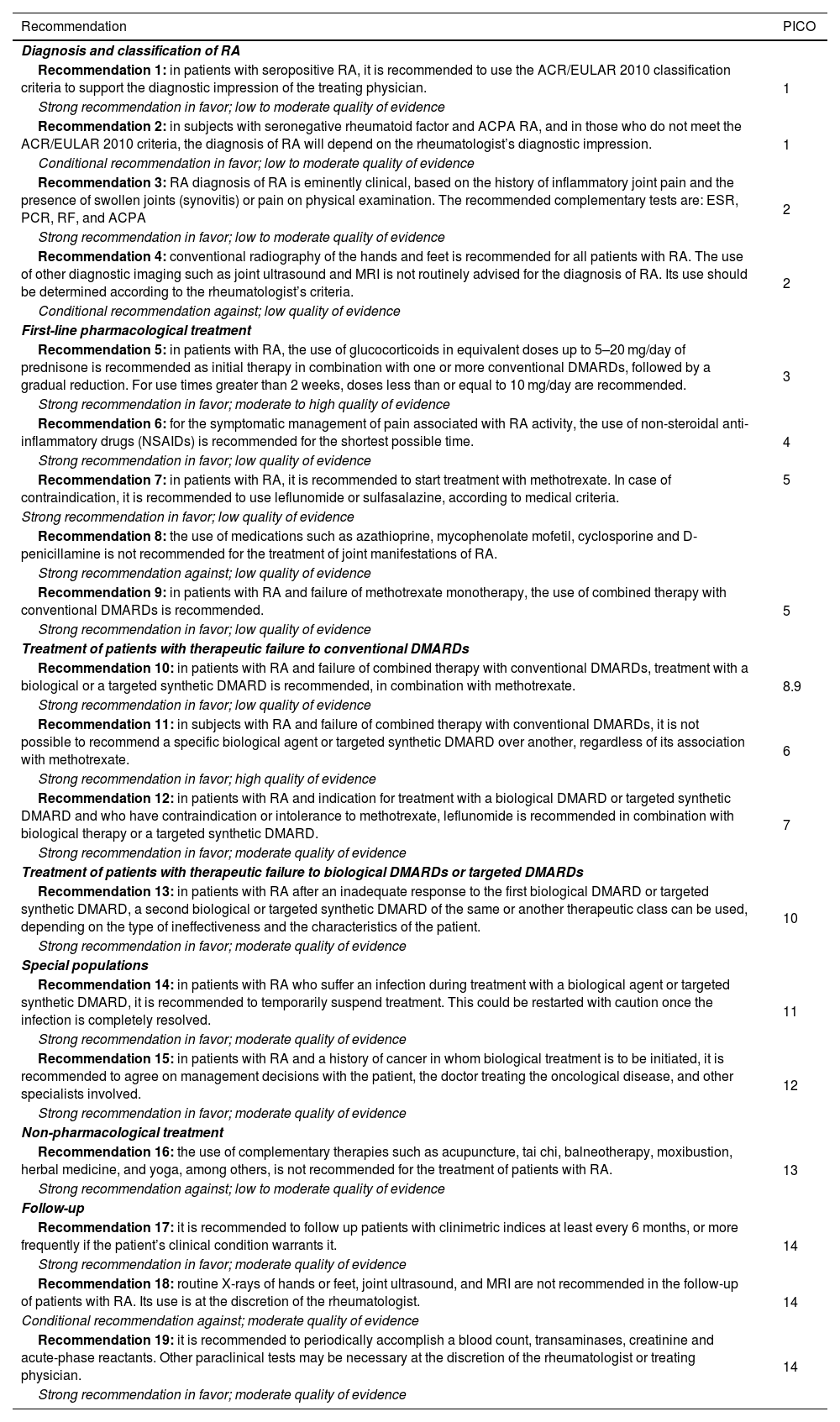

Table 3 and Fig. 1 summarize and outline the recommendations for the early detection, treatment, and follow-up of patients with RA.

Recommendations for the detection, treatment, and follow-up of patients with RA in Colombia.

| Recommendation | PICO |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis and classification of RA | |

| Recommendation 1: in patients with seropositive RA, it is recommended to use the ACR/EULAR 2010 classification criteria to support the diagnostic impression of the treating physician. | 1 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; low to moderate quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 2: in subjects with seronegative rheumatoid factor and ACPA RA, and in those who do not meet the ACR/EULAR 2010 criteria, the diagnosis of RA will depend on the rheumatologist’s diagnostic impression. | 1 |

| Conditional recommendation in favor; low to moderate quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 3: RA diagnosis of RA is eminently clinical, based on the history of inflammatory joint pain and the presence of swollen joints (synovitis) or pain on physical examination. The recommended complementary tests are: ESR, PCR, RF, and ACPA | 2 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; low to moderate quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 4: conventional radiography of the hands and feet is recommended for all patients with RA. The use of other diagnostic imaging such as joint ultrasound and MRI is not routinely advised for the diagnosis of RA. Its use should be determined according to the rheumatologist’s criteria. | 2 |

| Conditional recommendation against; low quality of evidence | |

| First-line pharmacological treatment | |

| Recommendation 5: in patients with RA, the use of glucocorticoids in equivalent doses up to 5–20 mg/day of prednisone is recommended as initial therapy in combination with one or more conventional DMARDs, followed by a gradual reduction. For use times greater than 2 weeks, doses less than or equal to 10 mg/day are recommended. | 3 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; moderate to high quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 6: for the symptomatic management of pain associated with RA activity, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is recommended for the shortest possible time. | 4 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; low quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 7: in patients with RA, it is recommended to start treatment with methotrexate. In case of contraindication, it is recommended to use leflunomide or sulfasalazine, according to medical criteria. | 5 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; low quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 8: the use of medications such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine and D-penicillamine is not recommended for the treatment of joint manifestations of RA. | |

| Strong recommendation against; low quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 9: in patients with RA and failure of methotrexate monotherapy, the use of combined therapy with conventional DMARDs is recommended. | 5 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; low quality of evidence | |

| Treatment of patients with therapeutic failure to conventional DMARDs | |

| Recommendation 10: in patients with RA and failure of combined therapy with conventional DMARDs, treatment with a biological or a targeted synthetic DMARD is recommended, in combination with methotrexate. | 8.9 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; low quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 11: in subjects with RA and failure of combined therapy with conventional DMARDs, it is not possible to recommend a specific biological agent or targeted synthetic DMARD over another, regardless of its association with methotrexate. | 6 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; high quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 12: in patients with RA and indication for treatment with a biological DMARD or targeted synthetic DMARD and who have contraindication or intolerance to methotrexate, leflunomide is recommended in combination with biological therapy or a targeted synthetic DMARD. | 7 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence | |

| Treatment of patients with therapeutic failure to biological DMARDs or targeted DMARDs | |

| Recommendation 13: in patients with RA after an inadequate response to the first biological DMARD or targeted synthetic DMARD, a second biological or targeted synthetic DMARD of the same or another therapeutic class can be used, depending on the type of ineffectiveness and the characteristics of the patient. | 10 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence | |

| Special populations | |

| Recommendation 14: in patients with RA who suffer an infection during treatment with a biological agent or targeted synthetic DMARD, it is recommended to temporarily suspend treatment. This could be restarted with caution once the infection is completely resolved. | 11 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 15: in patients with RA and a history of cancer in whom biological treatment is to be initiated, it is recommended to agree on management decisions with the patient, the doctor treating the oncological disease, and other specialists involved. | 12 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence | |

| Non-pharmacological treatment | |

| Recommendation 16: the use of complementary therapies such as acupuncture, tai chi, balneotherapy, moxibustion, herbal medicine, and yoga, among others, is not recommended for the treatment of patients with RA. | 13 |

| Strong recommendation against; low to moderate quality of evidence | |

| Follow-up | |

| Recommendation 17: it is recommended to follow up patients with clinimetric indices at least every 6 months, or more frequently if the patient’s clinical condition warrants it. | 14 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 18: routine X-rays of hands or feet, joint ultrasound, and MRI are not recommended in the follow-up of patients with RA. Its use is at the discretion of the rheumatologist. | 14 |

| Conditional recommendation against; moderate quality of evidence | |

| Recommendation 19: it is recommended to periodically accomplish a blood count, transaminases, creatinine and acute-phase reactants. Other paraclinical tests may be necessary at the discretion of the rheumatologist or treating physician. | 14 |

| Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence | |

ACPA: anticitrullinated protein antibodies; RA: rheumatoid arthritis; DMARD: disease-modifying antirheumatic drug; RF: rheumatoid factor; CRP: C-reactive protein; ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Algorithm for the prevention, evaluation, and management of rheumatoid arthritis in adults.

DMARD: disease-modifying antirheumatic drug.

1Glucocorticoids should be used at the lowest possible dose and discontinued as soon as possible.

2Leflunomide or sulfasalazine.

3It is recommended to carry out an appropriate assessment of cardiovascular risk, infection, and malignancy in patients.

4In case of contraindication or intolerance to methotrexate, consider the use of leflunomide.

Note: the evaluation of the patient with RA should include non-pharmacological considerations regarding therapeutic adherence, education and self-care, physical therapy, and rehabilitation, among others.

Recommendation 1: in patients with seropositive RA, it is recommended to use the ACR/EULAR 2010 classification criteria to support the diagnostic impression of the treating physician.

Strong recommendation in favor; low to moderate quality of evidence

Recommendation 2: in subjects with seronegative rheumatoid factor and ACPA RA, and in those who do not meet the ACR/EULAR 2010 criteria, the diagnosis of RA will depend on the rheumatologist’s diagnostic impression.

Conditional recommendation in favor; low to moderate quality of evidence

Good practice point: classification criteria are used in the field of clinical research and can be used to support the diagnosis of RA in patients who meet them. In any case, the rheumatologist must perform an individualized analysis to confirm or rule out the diagnosis.

Summary of evidence and panel discussionThe evidence obtained from 16 observational studies15–34 that compared the performance of 1987 against the 2010 criteria for RA classification, in general, agrees that the 2010 criteria applied in individuals with early-onset arthritis are more sensitive, but less specific than the 1987 criteria. However, their sensitivity is greatly reduced in patients with negative RF and ACPA, which can generate false negatives in these patients. In turn, subjects with few swollen joints, but who have a positive RF and a slight elevation of ESR, may be misclassified as RA. Experts note that the use of the 1987 criteria is part of the clinical judgment of the treating physician and that it is possible that there are individuals with established disease who meet the 1987 criteria and not those of 2010, so their use should not be ruled out in certain clinical situations.

Recommendation 3: RA diagnosis is eminently clinical, based on the history of inflammatory joint pain and the presence of swollen joints (synovitis) or pain on physical examination. The recommended complementary tests are ESR, CRP, RF, and ACPA.

Strong recommendation in favor; low to moderate quality of evidence

Good practice point: the recommended technique for measuring RF is nephelometry; for ACPA, the ELISA technique (at least second generation); for ESR, the Westergren method, and CRP, quantitative methods.

Recommendation 4: conventional radiography of the hands and feet is recommended for all patients with RA. The use of other diagnostic imaging such as joint ultrasound and MRI is not routinely advised for the diagnosis of RA. Its use should be determined according to the rheumatologist’s criteria.

Conditional recommendation against; low quality of evidence

Good practice points:

- •

Ultrasound and Magnetic Resonance Imaging may be useful in patients with suspected RA in whom the diagnosis is unclear.

- •

The use of ultrasound and nuclear magnetic resonance should be exclusive to the rheumatologist.

Five observational studies35–39 were identified that assessed the performance of ACPA and RF for the diagnosis of RA. In general, the evidence supports the use of RF and ACPA together and associates the presence of high ACPA titers with a worse prognosis. The expert panel considers that laboratory tests are complementary to the physical examination. Currently, the use of RF and ACPA accompanied by imaging studies is supported in cases where it is considered pertinent. However, these studies are not mandatory and should not delay diagnosis or the start of treatment.40,41 Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that patients who present typical RA lesions on diagnostic images, such as bone erosions, structural involvement, or characteristic extraarticular manifestations, can be directly diagnosed as RA.42

Regarding the use of diagnostic images, five studies43–47 were identified that evaluated the performance of joint ultrasound and nuclear magnetic resonance in RA diagnosis. About joint ultrasound, although it is useful for the detection of subclinical inflammation, no differences were identified concerning conventional radiography for bone erosion detection. Although some studies have reported that the use of joint ultrasound is related to earlier diagnosis and initiation of DMARDs, studies are not conclusive on this topic, and, in general, the quality of the evidence is low. The panel of experts considers that, in our setting, the use of ultrasound is limited by the low availability of trained personnel to perform this technique, in addition to being an operator-dependent study.

Evidence of the usefulness of MRI in the diagnosis of patients with RA comes from a systematic review46 that concludes that synovitis, osteitis, and erosions obtained with 1.5 Tesla MRI images are valid and useful to evaluate inflammation and joint damage for RA of the wrist/hand. However, this evidence comes from studies with high heterogeneity. Due to the quality of the evidence and the possible usefulness of this diagnostic image, experts consider that MRI should only be used in selected cases and at the discretion of the rheumatologist.

First-line pharmacological treatmentRecommendation 5: in patients with RA, the use of glucocorticoids in equivalent doses up to 5–20 mg/day of prednisone is recommended as initial therapy in combination with one or more conventional DMARDs, followed by a gradual reduction. For use times greater than 2 weeks, doses less than or equal to 10 mg/day are recommended.

Strong recommendation in favor; moderate to high quality of evidence

Good practice points:

- •

Glucocorticoids should be used for the shortest possible time and in the lowest effective dose, so the treating physician should consider the possibility of reducing and discontinuing these medications at each patient visit.

- •

In patients in whom the use of glucocorticoids is contemplated for 3 or more months, calcium supplementation plus vitamin D should be indicated, and the risk of fracture evaluated.

The evidence on the use of glucocorticoids in RA comes from moderate and high-quality clinical trials, in which the interventions are combined with DMARDs in different regimens.48–57 All regimens that combined DMARDs with glucocorticoids were effective in patients with early RA up to 2 years. The use of low doses (<10 mg/day of prednisone or its equivalent) in the initial treatment of RA has been shown to improve the signs, symptoms, and radiological progression of the disease, being associated with fewer side effects than the use of higher doses.48 In all the clinical trials reviewed, a gradual reduction of the initial dose of glucocorticoids is performed with the intention of discontinuing them.49 For more information, consult the ASOREUMA glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis Clinical Practice Guideline.

Recommendation 6: for the symptomatic management of pain associated with RA activity, the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is recommended for the shortest possible time.

Strong recommendation in favor; low quality of evidence

Good practice points:

- •

In the decision to administer a classic NSAID or a cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) inhibitor, gastrointestinal, renal, or cardiovascular risk factors should be considered, with special caution in patients receiving simultaneous NSAIDs and glucocorticoids, due to the risk of bleeding and gastrointestinal perforation.

- •

Avoid combined use of NSAIDs.

- •

In patients with gastrointestinal risk, consider the association of a proton pump inhibitor for a limited time.

The evidence regarding conventional analgesics in RA is scarce and generally comes from low-quality studies, with a small sample size and short duration, with a high risk of bias. The reports evaluate diclofenac and celecoxib in comparison with other analgesic treatments. The reported risk-benefit profile of diclofenac is comparable to that of other analgesic treatments.58 As for celecoxib, it may improve symptoms, relieve pain, and contribute to little or no difference in physical function compared to placebo. The results for short-term serious adverse events and cardiovascular events are uncertain.59 The panelists emphasize the need to assess the benefits and consider the risks in everyone to make therapeutic decisions and monitor those subjects managed with NSAIDs and glucocorticoids or with multiple medications due to the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding. Likewise, emphasis is placed on the rational use of proton pump inhibitors because, although these medications are safe and widely used, they are not free of adverse events.

Recommendation 7: in patients with RA, it is recommended to start treatment with methotrexate. In case of contraindication, it is recommended to use leflunomide or sulfasalazine, according to medical criteria.

Strong recommendation in favor; low quality of evidence

Good practice points:

- •

The recommended starting dose of methotrexate is 15 mg/week, orally, in a single dose or divided into two doses with a maximum interval of 24 h, with treatment adjustment according to response up to a maximum dose of 25 mg/week. In older adults, it may be necessary to reduce doses.

- •

In case of gastrointestinal intolerance and in some cases of lack of effectiveness of oral methotrexate, consider the use of the parenteral presentation approved in Colombia.

- •

Supplement with folic acid or folinic acid.

Based on moderate to high-quality evidence, significant clinical benefit (improvement in ACR50 response and functionality) of methotrexate (weekly doses between 5 and 25 mg) compared with placebo in short-term treatment (12–52 weeks) of RA patients was found, although its use was associated with a 16% discontinuation rate due to adverse events.60 Regarding the use of leflunomide, a systematic review that evaluated its efficacy and side effects with methotrexate in patients with RA as the first DMARD, reported an odds ratio [OR] of 0.88, with a 95% CI of 0.74–1.06 for the probability of achieving ACR 20 response, with a trend in favor of methotrexate, and a greater reduction in swollen joint count for methotrexate (mean difference = 0.82; 95% CI: 0.24–1.39). No differences were observed in tender joint count, physician global assessment, HAQ-DI, and serum CRP levels.61 The panel considers that the first therapeutic option in a patient with early RA is methotrexate. If contraindicated, leflunomide or sulfasalazine can be administered.

Concerning the use of parenteral methotrexate, the evidence comes from a meta-analysis that compared its efficacy with that of oral methotrexate in patients with RA and reported that the parenteral presentation was more likely to achieve a reduction in disease activity than the oral presentation.62 Due to the convenience in the administration of oral methotrexate, experts consider that this drug is of choice for the initiation of treatment in patients with RA; regarding parenteral methotrexate, they highlight that it is an option in cases of gastrointestinal intolerance to oral methotrexate and not necessarily as a prior step to escalating therapy.

Recommendation 8: the use of medications such as azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, and D-penicillamine is not recommended for the treatment of joint manifestations of RA.

Strong recommendation against; low quality of evidence

Good practice points:

- •

Consider the use of antimalarials as monotherapy only in patients with low inflammatory activity who do not have poor prognostic factors.

- •

In patients treated with antimalarials with remission of the disease, monotherapy with these medications could be continued.

Regarding azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil, cyclosporine, and D-penicillamine, no evidence was identified to demonstrate that they improve disease progression in terms of joint involvement. A systematic review, which aimed to assess the clinical efficacy of hydroxychloroquine in the joints of patients with RA, reported lower efficacy compared to methotrexate or sulfasalazine in monotherapy. Hydroxychloroquine, combined with other DMARDs, could increase clinical efficacy.63 The panel of experts considers that, due to its widespread use in Colombia, this medication can be considered in patients with low inflammatory activity who do not have poor prognostic factors, such as high-titer positive RF and ACPA, moderate or high activity at the beginning of the disease, failure of 2 previous conventional DMARDs or early structural damage. Additionally, those RA subjects with low inflammatory activity currently treated with hydroxychloroquine and disease control can continue using this medication.

Recommendation 9: in patients with RA and failure of methotrexate monotherapy, the use of combined therapy with conventional DMARDs is recommended.

Strong recommendation in favor; low quality of evidence

Good practice point: in selected cases, when the rheumatologist considers a high risk of disease progression, the use of a biological medication or a targeted synthetic DMARD could be considered, once failure to methotrexate used at an adequate therapeutic dose is documented for at least 3 months. The use of biological agents or targeted synthetic DMARDs in this scenario should be exclusive to rheumatology physicians.

Summary of evidence and panel discussionThe evidence regarding the use of combinations of DMARDs comes from clinical trials,64–66 with low to moderate certainty of the evidence, mainly due to imprecision. The findings suggest improvement in long-term disease activity of combination therapy; however, it is not conclusive regarding functional outcomes and remission, compared with monotherapy with conventional DMARDs. Considering the socioeconomic context and the Colombian health system, the preferred strategy includes combined interventions with conventional DMARDs in different regimens and with an early start within the “window of opportunity”.67,68 Only in selected cases, such as in those individuals with intolerance to methotrexate and leflunomide, can the use of a targeted synthetic biologic or DMARD be considered in this scenario.

Treatment of patients with therapeutic failure to conventional DMARDsRecommendation 10: in patients with RA and failure of combined therapy with conventional DMARDs, treatment with a biological or a targeted synthetic DMARD is recommended, in combination with methotrexate.

Strong recommendation in favor; low quality of evidence

Good practice points:

- •

In subjects over 50 years of age (especially in those over 65), the rheumatologist must consider cardiovascular risk factors, thromboembolic events, and malignancy when contemplating treatment with JAK inhibitors. If this risk is judged as high, it is recommended to evaluate the use of medications with other mechanisms of action.

- •

Before starting biological therapies, it is necessary to perform adequate risk management that includes a vaccination schedule and screening for endemic infections.

In terms of efficacy and safety, biological DMARDs and targeted synthetic DMARDs have demonstrated clinical benefit in patients with RA, both as monotherapy and in combination with methotrexate. Clinical trials comparing biological DMARDs with placebo in individuals previously treated with conventional DMARDs showed an effective reduction in signs and symptoms, regardless of the mechanism of action (anti-TNF or non-anti-TNF). Regarding JAK inhibitors, tofacitinib has been studied in multiple clinical trials and has demonstrated its effectiveness in monotherapy or combination with placebo in patients with RA without response to conventional DMARDs; baricitinib demonstrated efficacy compared to placebo in patients with a lack of response to conventional DMARDs and early RA as monotherapy or in combination with methotrexate; upadacitinib demonstrated to be effective compared to placebo in patients with RA without prior methotrexate or with lack of response to conventional DMARDs; and filgotinib was shown to be effective in reducing the signs and symptoms of RA in combination with methotrexate and as monotherapy.69

Regarding the safety of JAK inhibitors, a post-marketing study—ORAL Surveillance (ORALSURV)—assessed the safety of tofacitinib compared to anti-TNF therapy in subjects with RA over 50 years of age (especially in those over 65) with cardiovascular risk factors; an incidence rate of malignant neoplasms of 1.13 (95% CI: 0.87–1.14) was observed for individuals treated with tofacitinib at 5 mg/2 times a day, and 1.13 (95% CI: 0.86–1.14) for those treated with tofacitinib at 10 mg twice daily, compared with 0.77 (95% CI: 0.55–1.04) for patients treated with TNF inhibitors (hazard ratio [HR]: 1.48; 95% CI: 1.04–2.09). Based on these results, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) generated an alert that recommends treating physicians evaluate the risks and benefits of the use of JAK inhibitors in patients with RA, especially those with a history of smoking, cancer, and cardiovascular risk.70,71

Experts consider that the choice of treatment with a biological DMARD or a targeted synthetic DMARD is part of the criteria of the rheumatologist, who must perform a risk-benefit balance, especially in patients with cardiovascular risk factors or cancer history.

Recommendation 11: in subjects with RA and failure of combined therapy with conventional DMARDs, it is not possible to recommend a specific biological agent or targeted synthetic DMARD over another, regardless of its association with methotrexate.

Strong recommendation in favor; high quality of evidence

Good practice point:

In individuals over 50 years of age, the rheumatologist must consider cardiovascular risk factors, thromboembolic events, and malignancy when weighing up treatment with JAK inhibitors. If this risk is considered high, it is recommended to evaluate the use of medications with other mechanisms of action.

Summary of evidence and panel discussionConcerning the superiority of some biological medications over others, high-quality evidence from clinical trials that compared adalimumab vs. abatacept,72–74 rituximab vs. etanercept and adalimumab,75 certolizumab pegol vs. adalimumab,76 etanercept vs. adalimumab,77 sarilumab vs. adalimumab,78,79 and tocilizumab vs. adalimumab,80 is not conclusive, so it is not possible to recommend a certain biological agent over another.

Direct evidence for comparison between JAK inhibitors and anti-TNF revealed no clinically important differences in efficacy.81–83 Indirect evidence, from network meta-analysis, reported similar efficacy of biological DMARDs and JAK inhibitors. The preference of medications may be determined by their safety profile and cost-effectiveness.69

Recommendation 12: in patients with RA with an indication for treatment with a biological DMARD or a targeted synthetic DMARD and who have a contraindication or intolerance to methotrexate, leflunomide is recommended in combination with biological therapy or a targeted synthetic DMARD.

Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence

Summary of evidence and panel discussionThe evidence regarding the use of combinations of biological DMARDs with conventional DMARDs other than methotrexate comes from observational studies84–90 with moderate quality. The findings suggest that there are no differences in disease activity, functionality, and adverse events in combinations of leflunomide and anti-TNF compared with methotrexate plus anti-TNF or monotherapy. Leflunomide has demonstrated efficacy and adequate tolerance in clinical trials in patients with RA intolerant to methotrexate.

Treatment of patients with therapeutic failure to biological or targeted DMARDsRecommendation 13: In patients with RA, after an inadequate response to the first biological DMARD or targeted synthetic DMARD, a second biological or targeted synthetic DMARD of the same or another therapeutic class can be used, depending on the type of ineffectiveness and the characteristics of the patient.

Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence

Good practice point:

If the failure/inefficacy of the biological DMARD or targeted synthetic DMARD was considered primary, it would be advisable to use another biological DMARD or targeted synthetic DMARD with a different therapeutic target.

Summary of evidence and panel discussionThe moderate quality evidence comes from 2 systematic reviews 91,92 that assessed the efficacy of different biological DMARDs and targeted synthetic DMARDs in patients who had presented an inadequate response to the first anti-TNF. Greater efficacy was found for all biologics (anti-TNF and non-anti-TNF) and targeted synthetic DMARDs compared to placebo. There is a trend to observe greater efficacy of non-anti-TNF over anti-TNF after failure to anti-TNF.

About the efficacy of abatacept compared with an anti-TNF or other non-anti-TNF, conflicting results were found concerning the superiority of abatacept in subjects who failed an anti-TNF. No studies were identified that compared biological DMARDs with targeted synthetic DMARDs in the setting of therapeutic failure. With the available evidence, it is not possible to recommend one biological DMARD or targeted synthetic DMARD over another for the treatment of RA patients with anti-TNF failure.

Experts indicate that the cause of therapeutic failure must be evaluated to determine the conduct regarding treatment modification. When choosing treatment in the context of therapeutic failure of a first biological DMARD or targeted DMARD, in addition to efficacy, the safety profile and availability of the medication must be considered.

Likewise, in the case of patients with active disease and intolerance to conventional DMARDs and who require treatment with biological DMARDs or targeted synthetic DMARDs, there is some evidence that may favor the choice of using IL-6 inhibitors or JAK inhibitors in this context, but according to the group developing the CPG, it was not considered conclusive enough to develop a standard recommendation for all patients on monotherapy.

Special populationsRecommendation 14: in patients with RA who suffer an infection during treatment with a biological agent or targeted synthetic DMARD, it is recommended to temporarily suspend treatment. This could be restarted with caution once the infection is completely resolved.

Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence

Good practice point:

If the patient and the rheumatologist consider that the biologic was the main cause of the infection and there are fears about its reinitiation, the use of a different molecule or treatment scheme could be considered.

Summary of evidence and panel discussionThe evidence on restarting treatment in RA patients treated with biological medications is scarce and comes from observational studies14,93–96 with low quality of evidence. In the selected studies, it is reported that the rate of serious infection in patients treated with anti-TNF after a serious infection event is 18% patient/year compared to non-biological DMARDs (21.4% patient/year).14 In these real-life studies, it was observed that, after an infection that required hospitalization in RA patients who were being treated with anti-TNF, most subjects continued with the same anti-TNF and only a minority changed medications. The drugs with the lowest rates of subsequent serious infections are abatacept and etanercept.95

The expert panel agrees that individuals with special conditions such as severe infections should temporarily suspend biological treatment and restart it once the infection resolves. A change in treatment may also be considered if the infection is considered a consequence of the use of the biological agent.

Recommendation 15: in patients with RA and a history of cancer in whom biological treatment will be initiated, it is recommended to agree on management decisions with the patient, the doctor treating the oncological disease, and other specialists involved.

Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence

Good practice point: in subjects with RA and cancer who are undergoing oncological treatment, this takes precedence over the use of biologics for the treatment of RA. The biological medication could be used in patients with a history of cancer if, along with the doctor treating the oncological disease, it is agreed that the neoplasm is controlled and will not require further interventions that influence the therapeutic decision.

Summary of evidence and panel discussionThe evidence, of moderate quality, regarding the safety of treatment with biological drugs in patients with RA and cancer comes from cohort studies.97–103 Overall, no significant differences in overall survival were observed between patients who received biological agents and those who did not. However, there is insufficient information concerning other cancer outcomes, such as recurrence and progression, and there is no data to define the influence of each drug on cancer recurrence or survival in populations of patients with advanced cancer. This evidence does not allow us to recommend any specific biological treatment.

In patients undergoing oncological treatment (chemotherapy, radiotherapy, among others), treatment decisions must be taken in conjunction with the doctor treating the underlying oncological disease. To date, there is no evidence to recommend a specific biological treatment in cancer patients. Previously, caution was exercised over using anti-TNF in this population, as it was considered to increase the proliferation of tumor cells; however, this information has been reevaluated.104

Non-pharmacological treatmentRecommendation 16: the use of complementary therapies such as acupuncture, tai chi, balneotherapy, moxibustion, herbal medicine, and yoga, among others, is not recommended for the treatment of patients with RA.

Strong recommendation against; low to moderate quality of evidence

Good practice point:

In the treatment of patients with RA, joint management with physical medicine and rehabilitation, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and mental health (psychology and psychiatry), and pharmacotherapeutic follow-up should be considered.

Summary of evidence and panel discussionA search for evidence was conducted that included multiple non-pharmacological and non-surgical therapies, including physical activity, diet, acupuncture, tai chi, yoga, moxibustion, balneotherapy, among others.105–110 The only intervention with moderate to high-quality evidence that showed benefits in terms of pain and functionality was physical activity.110 For other non-pharmacological therapies, in general, the evidence is scarce, of low quality, and with inconclusive results.106–109 The panel of experts considers that it is necessary to emphasize the multidisciplinary management of patients with RA, considering not only rehabilitation but also mental health care and monitoring of adherence and drug interactions.

Follow-upRecommendation 17: it is recommended to follow-up patients with clinimetric indices at least every 6 months, or more frequently if the patient’s clinical condition warrants it.

Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence

Good practice points:

- •

Follow-up can be performed more frequently according to the patient’s features (functionality and comorbidities), the activity of the disease, and the established treatment.

- •

Monitoring of disease activity should be carried out with accepted clinimetric scales, such as DAS 28, SDAI, CDAI, and RAPID3, among others.

- •

For the evaluation of functionality, the use of HAQ (mHAQ or HAQ-DI) is suggested.

- •

In the context of telemedicine, one of the accepted scales for the evaluation of activity and functionality should also be used.

Recommendation 18: routine X-rays of hands or feet, joint ultrasound, and MRI are not recommended in the follow-up of patients with RA. Its use is at the discretion of the rheumatologist.

Conditional recommendation against; moderate quality of evidence

Recommendation 19: it is recommended to periodically accomplish a blood count, transaminases, creatinine, and acute-phase reactants. Other paraclinical tests may be necessary at the discretion of the rheumatologist or treating physician.

Strong recommendation in favor; moderate quality of evidence

Good practice point:

The treating physician must assess the comorbidities, cardiovascular, and metabolic risks of the patient with RA, with prompt referral for their control.

Summary of evidence and panel discussionThe evidence regarding the parameters for monitoring patients with RA is heterogeneous and of moderate quality, with differences in assessment methods and comparators. Published data indicate that all activity indices that include swollen joints are related to radiographic progression, while of the individual components, only swollen joints and acute-phase reactants are associated with this outcome.111 The expert panel considers that composite activity indices are the optimal tool to monitor disease activity in RA, and the frequency of their application and patient follow-up will depend on patients’ characteristics, disease activity, and established therapy, among others, which must also be defined by the treating doctor.

Regarding the use of images for the follow-up of patients with RA, the evidence is scarce and of moderate quality.112,113 Ultrasound and resonance studies can be a useful complement to evaluate the patient’s response to treatment; however, the findings require further validation. The panel of experts considers that routine imaging for the follow-up of patients with RA is only necessary in those cases selected by the rheumatologist.

Applicability, dissemination, and implementationThis guideline, produced by the Colombian Association of Rheumatology, aims to guide the decision-making of health professionals in charge of caring for patients with RA in Colombia. The recommendations were constructed considering the socioeconomic context of the country and the structure of the health system, based on the most recent evidence regarding the diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of RA, with the expertise of a group of rheumatologists from different regions of the country and the perspectives of patient representatives.

After the analysis of the determining factors for the implementation of this guideline, the coverage of the Colombian health system (close to 100%) and the inclusion of most of the medications and paraclinics recommended in this guideline in the health benefits plan were identified as facilitating factors. Resistance to change on the part of health professionals, lack of training of health personnel to care for these patients, absence of availability of laboratory and imaging tests in certain regions of the country, the lack of personnel trained in performing joint ultrasound, the difficulties in accessing specialized assessment (internal medicine and rheumatology), and the absence of educational programs and comprehensive care for patients with RA, were identified as barriers that must be overcome.

Thus, to put this guideline into practice, health personnel must be socialized at all levels of care and together with the corresponding government entities and the entities that administer the benefit plans, and access to specialized assessment for rheumatology must be guaranteed in all regions of the country, which can be developed with structured telemedicine programs. Other actions necessary for the implementation of the guidelines include ensuring access to laboratories, images, and medications throughout the national territory and promoting the creation of educational and comprehensive care programs for patients with RA.

Concerning the potential impact of this guideline on the use of resources, although no economic studies were carried out to determine the cost-effectiveness of each of the interventions in our context, in general, it is considered that they do not lead to the use of additional resources, since, as previously mentioned, the vast majority of the technologies (paraclinical and medications) recommended in this guideline are included in the health benefits plan and the judicious and phased use of the therapies suggested here leads to a rational use of higher cost medications.

The dissemination of this guideline will be done through publication in the Revista Colombiana de Reumatología, the official organ of ASOREUMA, through free access, and socialization at academic events supported by the Association.

To support the implementation process, assess adherence to the recommendations and the impact of the CPG, the indicators for audit and evaluation of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection Specific to AR are adopted, which can be consulted in the Supplementary material 7. The indicator board covers aspects of structure (characteristics of the health system), process (measurement of adherence), and results (consequences or outcomes in health), applicable to the implementation of the CPG.

FinancingThis CPG was developed in its entirety by the Colombian Association of Rheumatology (ASOREUMA), which received financial support from AbbVie. However, ASOREUMA developed this CPG independently, and the funders were not involved in the development, guideline content, or final recommendations.

Conflict of interestAll participants in this CPG declared their interests related to its development and none of them presented a conflict of interest.

Thematic experts: Paola Coral Alvarado, Wilson Bautista, Jairo Hernán Cajamarca, Luis Javier Cajas, Sebastián Herrera Uribe, María Constanza Latorre, Yimy Medina, Javier Ramírez Figueroa, Diana Nathalie Rincón, Wilmer Gerardo Rojas, Diego Saaibi, Lina María Saldarriaga, Adriana Vanegas, Kelly Vega, and Juan Manuel Bello.

Patient Representatives: Maria Mercedes Rueda, Luz Maria Sierra, and the Colombian Foundation for Rheumatic Support (FUNDARE).

Methodological team: Linda Ibatá, Susan Martínez, and EpiThink Health Consulting.