The prevalence of rheumatic disease in the general population is approximately 10%. At the same time, there has been an increase in the workload of rheumatology services, particularly concerning consultations. Many health institutions have limited the duration of rheumatology consultation to about 15 min. This article demonstrates the need to lengthen the duration rheumatology consultations.

ObjectiveThe goal of this work is to review the literature about the standards for the duration of rheumatology consultations and to propose new organizational strategies in this regard.

Materials and methodsA narrative review of the current literature related to care standards in rheumatology consultations was carried out, including the wide variety of diagnostic procedures, which decisively influence the duration of these consultations.

Results and discussionOrganizational strategies are proposed, based on classifying consultations into first, second, and follow-up visits, with a specific daily number, and giving more time to the first two types of consultations. Although this planning implies greater effort on the part of administrative staff, it will undoubtedly result in a better quality of care for rheumatology patients.

Las enfermedades reumáticas tienen aproximadamente 10 % de prevalencia en la población general. Paralelamente, se ha experimentado un aumento de la carga de trabajo en los servicios de reumatología, en particular en las consultas. Muchas instituciones de salud han limitado el tiempo de la consulta de reumatología a unos 15 minutos. En este artículo se demuestra la necesidad de alargar la duración de dichas consultas.

ObjetivoEl objetivo de este trabajo es revisar la literatura sobre los estándares de la duración de las consultas de reumatología y proponer nuevas estrategias organizativas al respecto.

Materiales y métodosSe llevó a cabo una revisión narrativa de la literatura actual relacionada con los estándares asistenciales de las consultas de reumatología que incluyen la aplicación de una gran variedad de procedimientos diagnósticos, lo que influye decisivamente en la duración de dichas consultas.

Resultados y discusiónSe proponen estrategias de organización basadas en la clasificación de las consultas en primera, segunda y de seguimiento, con un número diario determinado de cada una, y una mayor duración para las dos primeras. Aunque estas estrategias organizativas implican un esfuerzo mayor por parte del personal administrativo, sin dudas redundarán en una mejor calidad asistencial a los pacientes de la consulta de reumatología.

Rheumatic diseases constitute an important public health problem: in recent years a considerable increase in the prevalence of these diseases has been detected and it is estimated that approximately 10% of the world's population suffers from one of these conditions.1,2

The classification of rheumatic diseases is sometimes difficult due to the unknown etiology and the heterogeneity in their clinical presentation. Osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis are the 2 most common rheumatic diseases and account for a large percentage of disability.3

Rheumatic diseases share manifestations of inflammation or pain in the various structures of the musculoskeletal system, with frequent autoimmune alterations and systemic involvement.4 Laboratory tests and imaging studies guide or confirm the presence of a rheumatic disease as long as they are interpreted in the clinical context of the patient,5 because the basis for the diagnosis of a rheumatic disease is clinical.

Morbidity and mortality in rheumatic patients decreases significantly when an early diagnosis is made and treatment is implemented. For this reason, the cornerstone of a rheumatology service is the consultation, where the patient-rheumatologist bond is established. For example, in the case of rheumatoid arthritis, the implementation of early treatment can delay or stop joint deterioration, thus improving the quality of life of the patients.6

The exhaustive physical examination and the interrogation to each patient who attends a consultation of rheumatology are crucial to determine the diagnosis and consume time that is impossible to shorten. The "hurry" of the consultation can result in a decrease in the quality of the service. Based on this concern, studies have been conducted aimed at establishing quality standards for rheumatology care7,8 that propose minimum times for consultations.

The purpose of this article is to review the literature on the standards of duration of the rheumatology consultation and propose a new organizational strategy in this regard.

About the rheumatological examinationIn order to highlight the complexity of the diagnostic process and justify the need to carry it out carefully, fundamental aspects to take into account in the rheumatological clinical examination are summarized below9:

- □

Location and symmetry of the pain or the lesions.

- ○

Determine whether the problem is regional or generalized, symmetrical or asymmetrical, peripheral or central.

- ○

- □

Onset and chronology of the symptoms.

- ○

Establish the date of onset of symptoms and their evolution.

- ○

- □

Examination of the joints and surrounding soft tissues, bones, and individual muscle groups involved in the movement of the affected area.

- ○

Ask the patient about the circumstances around which the symptoms started (acute, subacute or chronic) and the types of movements that aggravate them.

- ○

Inspect all areas of the joints looking for signs of inflammation (warmth, tenderness at the joint line, pain with active or passive movement, particularly at the extremes of the range of motion, and intra-articular swelling or effusion), deformities, muscle weaknesses and atrophies, erythema, lack of muscle strength, among others.

- ○

Palpate the joints of the limbs looking for changes in temperature.

- ○

Palpate the joint line and major bone and soft tissue structures to assess sensitivity.

- ○

- □

Examination of the tendons, menisci and ligaments.

- ○

Inspect these components of the musculoskeletal system, because they may or may not be the primary source of the rheumatic disease.

- ○

- □

Systemic and extra-articular aspects.

- o

Ask about fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, among other symptoms that indicate the presence of an underlying medical disorder that could predispose to a specific rheumatological problem.

- o

- □

Functional losses.

- ○

Ask about possible functional losses or impairments, from mild (difficulty getting dressed) to severe (difficulty walking).

- ○

- □

Family history.

- ○

Ask the patient about the family pathological history, since several rheumatic diseases have a genetic basis.

- ○

According to the aspects of the rheumatological examination, it is important to recognize the role of the clinic as the cornerstone in the diagnostic process of the rheumatic diseases.

About the standards for a rheumatology consultationThe time assigned to each consultation is a critical factor for the proper diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of patients. It should not be forgotten that in consultations health professionals must perform functions, not only in the healthcare field, which include those mentioned above, but also actions of prevention and health education with the patients.

The ideal duration of a rheumatology consultation is that which allows the rheumatologist to obtain and analyze the information necessary to establish an accurate diagnosis, indicate a treatment and evaluate the evolution of the patient.

The factors that can affect the duration of a consultation are of a very varied nature.7 For example, an important factor is the experience of the rheumatologist. Although it is not so evident that the most experienced takes less time, it is recognized that the management of patients must be more fluid. In addition, the presence of other health professionals (nurses or other doctors) contributes to the rapid development of a consultation. For example, the convenience of a nurse specialized in the rheumatology service has been raised.10

In order to optimize the organization of the consultations, it has been proposed to differentiate them according to the time at which the patient attends. Thus, the consultations would be classified as follows:

First consultationIn the first interrogation and physical examination of the rheumatological patient, a large number and variety of diagnostic procedures11 are applied and complementary examinations are indicated. On this first visit, the minimum set of data that must be included are: a) reason for the consultation; b) anamnesis; c) physical exploration; d) complementary explorations (provided by the patient and requested); e) diagnostic orientation; f) therapeutic recommendations, and g) need for revisions and recommended term.8

The Spanish and British Societies of Rheumatology agree that the average duration of the first consultation is approximately 30 ± 5 min,7,12 although for systemic and inflammatory diseases these consultations are of approximately 40 ± 7 min.7

Second consultationIt includes the review of laboratory tests and images to issue or corroborate a diagnosis and indicate a treatment. In this visit the minimum set of data that must be included are: a) record of incidents from the previous visit; b) assessment of the complementary explorations; c) clinical judgment of the patient’s condition; d) diagnosis; e) therapeutic recommendations, and f) need for reviews and recommended term.8

The duration of this second consultation has been estimated at approximately 19 ± 3 min.7

Follow-up consultationThe specialist assesses the evolution of the patient, the effects of the treatment, and changes are made if necessary. In this type of visit, the minimum set of data that must be included are: a) record of incidents from the previous visit; b) physical exploration; c) clinical judgment of the patient’s condition with respect to the previous visit; d) therapeutic recommendations, and e) need for revisions and recommended term or discharge.8 In addition, the rheumatologist should review the treatment with the patient to detect and resolve problems related to its efficacy, safety, and adherence to treatment.8 In cases of medical discharge, a written report must be issued, delivered to the patient and recorded in the medical history.8

Follow-up visits have been timed at approximately 17 ± 3 min.7

For patients with systemic and inflammatory diseases, the 3 types of consultations record an average of 5–10 min longer compared to those reported previously.7

About the duration of rheumatology consultationsIt has been recommended that a rheumatologist should not see more than 5 initial consultations or more than 11 patients in total on the same day.7,8 The proposals developed in this article do not conform to what has been established, since they contemplate a greater number of consultations in the same session. However, they allow to increase the current consultation time and thereby improve the quality of care for these patients.

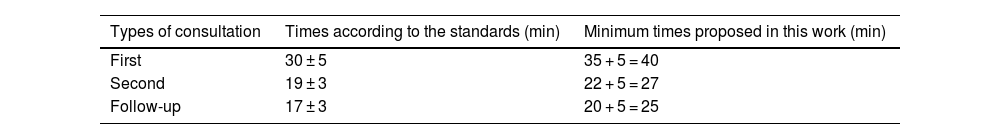

In this article, considering everything related to the thoroughness of the rheumatological clinical examination, as well as the real context in which rheumatology specialists work in daily practice, certain increases in the time dedicated to each type of consultation are proposed (Table 1).

Duration times for different consultations.

| Types of consultation | Times according to the standards (min) | Minimum times proposed in this work (min) |

|---|---|---|

| First | 30 ± 5 | 35 + 5 = 40 |

| Second | 19 ± 3 | 22 + 5 = 27 |

| Follow-up | 17 ± 3 | 20 + 5 = 25 |

The times proposed in this article start with the upper value of the time interval established in the standards and 5 min are added to contemplate the transition from one patient to the next.

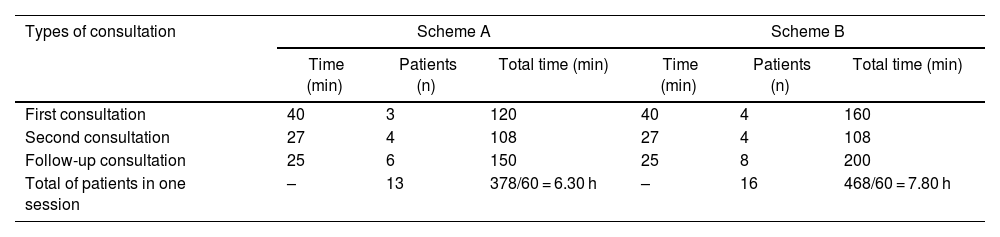

New schemes for planning consultations are proposed in this paper, which contemplate not only increasing the time with each patient, but also the total duration of the consultation session: The starting point is to increase the consultation session by 3 h: from the 5 h proposed in the international standards,7 up to 8 h in a consultation session, taking into account the possibility of applying these schemes in public health care systems or in private practice. Thus, a consultation session could be organized according to one of the schemes presented in Table 2.

Schemes for planning a consultation session.

| Types of consultation | Scheme A | Scheme B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (min) | Patients (n) | Total time (min) | Time (min) | Patients (n) | Total time (min) | |

| First consultation | 40 | 3 | 120 | 40 | 4 | 160 |

| Second consultation | 27 | 4 | 108 | 27 | 4 | 108 |

| Follow-up consultation | 25 | 6 | 150 | 25 | 8 | 200 |

| Total of patients in one session | – | 13 | 378/60 = 6.30 h | – | 16 | 468/60 = 7.80 h |

Schemes A and B, which are based on the times recommended in this work, differ only in the number of patients who consult in each session, with the consequent differences in the total times of the consultation session.

On the other hand, in the reviewed literature it is established that a specialist should not have more than 4 consultation sessions a week, in order to give time to other healthcare, teaching and research activities as well as his/her own training as a specialist.7

The proposed schemes are not rigid, so they can serve as a guideline to take into account when organizing consultation sessions. It is recommended that rheumatology consultations take place in the afternoon at least once a week, in order to facilitate patient accessibility.8

In addition, the possibility of treating in the day patients who have attended consultations without an appointment due to worsening of their illness, unexpected event or referral from the emergency department should be considered.8 Furthermore, the hospital organization must ensure that no more appointments than scheduled are given.

The virtual consultationTelemedicine is also a tool for doctor-patient communication,13 through synchronous and asynchronous consultations.14 The use of information and communication technologies has been increasing because technological advances are no longer exclusive to the upper social classes.15 It is common that people with few economic resources have at least one cell phone, so the patient and the doctor can communicate virtually. Furthermore, it is possible that certain patients who live far from the hospital, or who are physically limited, may find advantages in this type of consultation.16 In fact, it has been proven that the percentage of non-attendance at virtual consultations is much lower than at face-to-face consultations.17 On the other hand, there will always be the group of young patients, or not so young but with computer skills, who will welcome the idea of virtual consultation.

Currently, several telemedicine applications have been developed for mobile phones, although the cost and logistics of implementing these systems are difficulties to overcome for the establishment of this modality in health services.18 Obviously, rheumatology teleconsultation would be restricted to some of the follow-up consultations.19 However, they should be included in the time fund for specialist consultations. Otherwise, it would be chaotic.

Although evidence on telemedicine care in rheumatology is limited and is still emerging, telerheumatology visits have been found to be non-inferior to in-person visits and are often more cost-effective in time and financial resources for patients.13,15 Even though doctors and patients note the lack of a physical exam in this type of consultation, in general, both have positive attitudes toward the use of telerheumatology15 and agree on its usefulness, for example, in the follow-up of many rheumatic diseases that require frequent monitoring of the results reported by the patients.20

Frequency with which patients should attend consultationsIt is estimated that a patient should attend approximately 4 consultations per year (first, second and 2 follow-ups, although this depends on the disease in question).7 The maximum waiting time between the onset of symptoms and the first consultation should not exceed 4 weeks. The time between the first and second consultation should not be longer than 2 weeks. The maximum separation interval for the rest of the follow-up visits ranges between 3 months for patients with inflammatory and systemic diseases and 9 for patients with metabolic bone diseases.7,21

According to the functioning of the out-of-hospital care area, it has been assumed that the rheumatologist should only follow certain groups of patients (inflammatory joint diseases, connective tissue diseases and a small percentage of other rheumatic diseases such as osteoporosis and microcrystalline arthropathies). There will be cases successfully controlled by the rheumatologist (osteoporosis, gout, osteoarthritis, among others) that could continue their follow-up in primary care.7

Evolution of a rheumatology serviceThe Spanish Society of Rheumatology and the American College of Rheumatology consider that, to guarantee the correct rheumatological care, a rheumatologist for every 40,000–50,000 inhabitants is needed as a minimum in the health area.7

In routine clinical practice, a progressive demand for care, with similar human and material resources, often leads to an increase in the number of consultations per doctor, with the consequent deterioration in quality. For example, a rheumatology service is established in a hospital in a community that did not have one. At the beginning, the rheumatologist will have few patients, but over time this number will increase, especially because primary care doctors know that they can refer patients to these specialists.

Non-medical considerations about consultation time in rheumatologyIt is important to note that the medical computer system entails a delay of 10–15 min in completely filing out the information of a patient. This time varies according to the ease of each professional in using computer systems. In addition, the time spent filling out forms required by the quality or statistics departments or by the patients themselves in the form of references, counter-references, insurance reimbursements, among others, is added.

It should be clarified that filling out a digital medical record also depends on the quality of the electrical energy service and web servers. If something does not work properly, the filing out of the medical history takes longer than estimated, or is postponed until the end of the work day, when the energy or Internet service is working properly, exceeding the stipulated working hours.

ConclusionsGiven the complexity of the rheumatological clinical examination and the need to pay due attention to these patients, the use of times longer than the 15 or 20 min currently available is mandatory.

Although the differentiation of consultations according to the classification into first, second and follow-up will require additional effort on the part of the staff in charge of granting appointments, we are sure that this measure will improve the quality of the rheumatology service.

The methodology proposed in this article in relation to the time for consultations and the organization of human resources should contribute to improving the quality of care in a rheumatology service. The schemes proposed are not rigid and can serve as a guideline to take into account to effectively organize consultation sessions.

CRediT authorship contribution statementThe authors were in charge of the conception, design and writing of the manuscript and assume full responsibility for its content.

Ethical considerationsThis manuscript is entirely original and is based on other published works duly cited in this document. It is a reflection on the need to put patients at the center of medical care and the efficient use of time in rheumatology consultations. It does not include studies on humans or animals. No artificial intelligence-assisted tools were used during the preparation of this work.

FundingNone.

To our dear family, thank you for being on every step of this academic journey. Your unwavering love and unconditional support have given us the strength and confidence to face the obstacles and pursue our goals. Your words of encouragement and comforting hugs have always been our refuge, and for that we are eternally grateful.

To our professors, your dedication and passion for teaching have been fundamental in our academic development. Each of your lessons, your guidance and your valuable feedback have helped us grow as professionals and as individuals. Your commitment to our success has been inspiring and has motivated us to surpass our limits.