Blue finger syndrome (BFS), usually noted by the violet or blue coloration of one or more fingers, may be the first manifestation of several diseases. These may present with alterations directly on the fingers or be the expression of systemic diseases. The most common pathophysiological causes are thrombosis, embolism, severe vasoconstriction, or vasculature involvement that may be inflammatory or non-inflammatory.

A description is presented of 5 cases of BFS, where the emphasis is placed on the importance of early diagnosis. The concept of evaluation and approach as a medical emergency is also stressed, because depending on this, it could reduce irreversible complications, such as necrosis and/or amputation.

El síndrome de dedo azul se caracteriza por la coloración violácea o azul de uno o más dedos, puede ser la primera manifestación de múltiples enfermedades, tanto las que presentan alteraciones directamente en los dedos o ser la expresión de enfermedades sistémicas; los mecanismos fisiopatológicos más comunes son trombosis, embolia, vasoconstricción grave o afección del lecho vascular que puede ser inflamatoria o no inflamatoria.

Describimos 5 casos de SDA, donde resaltamos la importancia del diagnóstico temprano y enfatizamos en el concepto de evaluación y abordaje como una urgencia médica, sin importar la causa, ya que su manejo y tratamiento inicial, más el intento de lograr un tratamiento dirigido a una etiología podría disminuir complicaciones irreversibles como la necrosis o amputación.

The blue finger syndrome (BFS) was first described by Feder in 1961; the patients presented the BFS associated with the initiation of therapy with coumarin agents.1 BFS is defined as the change in color to a violet-blue tone of one or more fingers, its presentation may be acute of subacute, usually affecting multiple fingers of the lower limbs; however, it can affect only one toe or occur in the upper limbs, it is commonly associated with pain in the area with alterations of coloration.2 Once ischemia is established, loss of tissue and ulceration occur, increasing the risk of infection and gangrene.3 The final consequences are limb loss or life-threatening conditions.4

There are multiple etiologies that are associated with this semiological sign, and this is why it is required to have a broad knowledge thereof to develop an adequate clinical approach and avoid irreversible complications in the patient.3 We present five clinical cases of BFS with different etiologies, where the clinical diagnosis is not always conclusive. The most relevant point is the diagnostic process and the objective is to rule out potentially fatal diseases.

Case 1A 62-year-old woman with pain of 2 months of evolution in the lower limbs, associated with violaceous coloration of the toes and vesicles, that when ruptured drain serous material, with a history of consumption of alcoholic beverages in the youth an exposure to wood smoke. The rest of the antecedents were negative. The paraclinical tests report: negative ANAS, IgG and IgM anticardiolipin antibodies within normal limits, complement C3 in 153 and C4 in 16.6 (not consumed), negative ENAS, cryoglobulins >32 (positive), immunofixation of proteins with presence of gamma band of kappa chain IgG >4200 (high), IgA: 186 (high), IgM: 60 (normal) and IgE: 64 (normal), protein immunoelectrophoresis with monoclonal peak in gamma band: 45.6%, the rest of infectious paraclinical tests are negative. With the results, a BFS secondary to cryoglobulinemia is considered.

Case 2A 77-year-old woman who consulted for violaceous coloration and coldness of 4 fingers of the right hand and 3 fingers of the left hand over the past 5 years; refers that when these symptoms started she had violaceous coloration on all finger pads. On the review by systems the patient referred occasional xerophtalmia and xerostomia, without oral ulcers or photosensitivity; mechanical knee pain, involuntary weight loss of 4kg in 4 months. High blood pressure and depressive disorder as unique antecedents. Studies were started to rule out occult neoplasm (mammography, cytology, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, colonoscopy, carcioembrionyc antigen, Ca 19-9, alpha-fetoprotein, abdominal ultrasound and chest X-ray), which did not show any abnormality; arterial Doppler of upper limbs and echocardiogram are also performed, which are reported as normal. Total cholesterol: 212, creatinine: 0.85, BUN: 13, triglycerides: 116, GOT: 28, GPT: 20, alkaline phosphatase: 217, phosphorus: 4.1. TSH: 0.59, ANAS: 1/80 with speckled pattern, negative ENAS, normal C3: 107.1 and C4: 29.1, negative antiphospholipid syndrome profile, normal blood count, and normal conduction velocities in upper limbs without peripheral neuropathy. Management was started with vasodilators, ASA and corticosteroids, with which her clinical picture improved.

Case 3A 67-year-old woman, Afro-descendant, who presented with a blue finger on the left lower extremity during the development of sepsis of abdominal origin secondary to biliary peritonitis due to acute cholecystitis, that required management with broad-spectrum antibiotics and multiple washings of the abdominal cavity during her stay in the intensive care unit (ICU), in addition to the use of vasopressor agents and mechanical ventilation. A Doppler of the lower limbs was performed, ruling out vascular obstructive etiology, the change in coloration persisted, and in addition was associated with distal cyanosis and skin sloughing in the anterior and posterior regions of the base of the finger. Hyperpigmented punctate lesions in palms and soles (Fig. 1). Profiles of antiphospholipids and cryoglobulins were carried out, which were negative, therefore, it was considered that the patient had a BFS secondary to systemic hypoperfusion and use of vasopressors.

Case 4A 54-year-old woman who is admitted due to altered state of consciousness. A violaceous coloration is observed on fingers 3, 4 and 5 of the left hand (Fig. 2). The patient has no important antecedents, and she did not take medications. During her hospitalization the neurological changes revert, but a left parietal cerebral infarction is documented, and it is possible to evidence by means of a Doppler study the presence of a thrombus in the right ulnar artery and, due to desaturation, a chest angiography is performed, with which a pulmonary thromboembolism of the right interlobar artery is diagnosed. It is considered to be a hypercoagulability syndrome, and for this reason, anticoagulation is initiated. The studies report negative ANAs, negative ENAs and negative antiphospholipid profile. Screening for occult neoplasm is done, discarding masses at the level of the thorax, abdomen, breasts, as well as gynecological. The patient remains anticoagulated due to her multiple thrombotic events, which limits the totality of hypercoagulability studies. The study is completed with cryoglobulins, cold agglutinins and protein electrophoresis, which are normal. Finally, it is not possible to recover the perfusion of the phalanges and requires amputation and subsequent discharge with anticoagulation for an indefinite period of time.

Case 5A male patient with frequent cocaine use, who is admitted due to pain and coloration changes in the distal area of the 5 fingers of the left hand (Fig. 3). A 24h electrocardiogram (Holter) and an echocardiogram are performed, which discard cardioembolic origin. Due to similar episodes, but no so severe, it had been requested a protein electrophoresis, which have no alterations. ANA and ANCA, which were previously positive, were requested, and on this occasion they were equally positive but with low titers, in addition with low complement and proteinuria. Given the suspicion on previous hospitalizations of SLE or renal compromise by pauci-immune vasculitis, is requested a renal biopsy, whose result was focal and segmental sclerosis with deposits of IgA without extracapillary proliferation or crescents; after reviewing previous hospitalizations in which is observed that the titers of antibodies increase with the periods of cocaine use, as well as the renal commitment. It is considered that it is a patient in whom the cause of vasoconstriction is the cocaine use and the positivity and variation in the titers of the antibodies is part of the cocaine/levamisole syndrome. In this occasion the patient underwent an amputation of the affected phalanges.

DiscussionThe BFS is associated with multiple systemic diseases. The first case is a woman in the seventh decade of life, in whom a violaceous coloration on the toes is documented. The extension paraclinical tests report positive cryoglobulins, and underlying hepatitis C was ruled out, therefore, it constitutes an etiology of blood hyperviscosity, which is a clearly known cause of BFS.5 The second case describes a clinical picture of 5 years of evolution in an older adult patient, ruling out as a first possibility a paraneoplastic vascular acral syndrome, in addition with paraclinical tests negative for systemic immunologic diseases, so empirical management was started with steroids achieving a good clinical evolution, thus considering that the patient has a BFS secondary to a possible inflammatory vasculopathy. Regarding the third case, it is a critically ill patient, secondary to sepsis of abdominal origin, requiring to stay in the ICU, with alterations of the distal perfusion and requirement of high doses of vasopressors, which is why it is a BFS secondary to a decrease in the arterial flow, a complication associated with the use of vasopressors, an adverse effect of these medications which is relatively common in the ICU.6 The fourth case is a patient with multiple thrombotic events and ischemic involvement of 3 fingers that required amputation, ruling out multiple etiologies and remaining thrombophilia as a working diagnosis; due to the need for early and indefinite anticoagulation, it is not possible to study the thrombophilia of the patient. The last case corresponds to a patient with cocaine use, also with immunological, hematological and renal alterations, which has previously been diagnosed as an effect of the cocaine/levamisole syndrome. In this occasion is admitted for severe ischemia of the fingers of the left hand that must be amputated; this last case shows a new cause of BFS.7,8

It is important to highlight that when an early diagnosis is not reached, the consequences of the BFS can be irreversible. Taking into account the analysis of the cases it is important to know the pathogenic mechanisms and the possible causes and diagnostic approach of this syndrome.

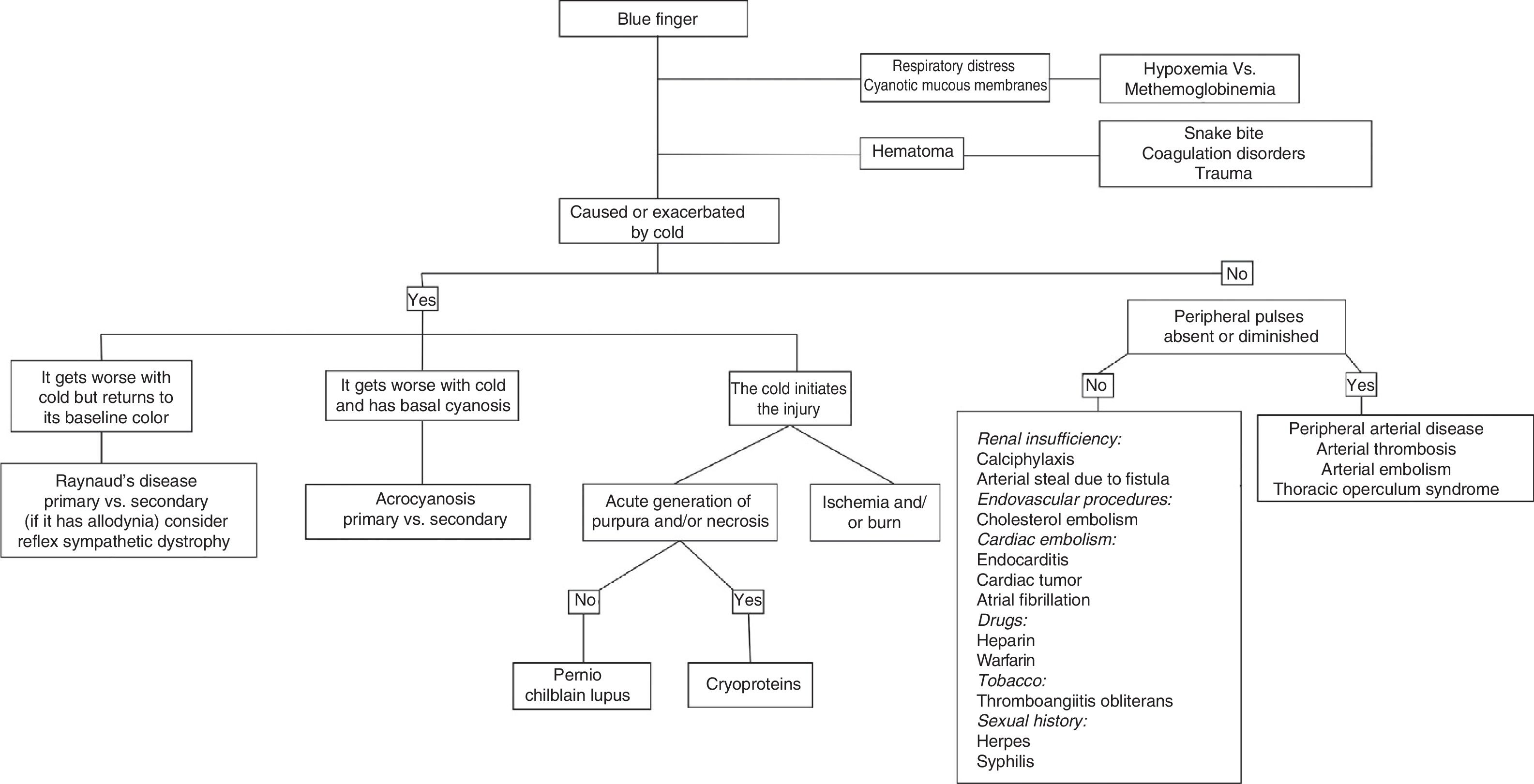

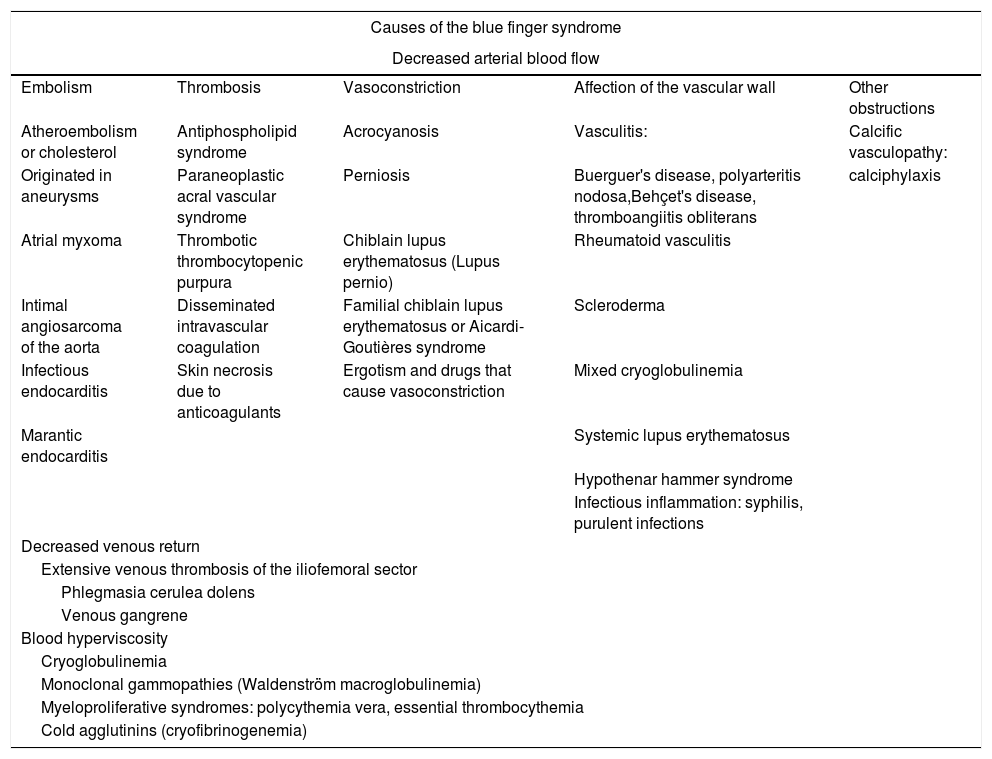

Pathogenic mechanisms of the blue finger syndromeThe causes of BFS exclude, in the first instance, a local previous trauma and situations that explain generalized cyanosis, such as hypoxemia, hypothermia or methemoglobulinemia. The most frequent pathophysiological mechanisms include the decrease in arterial flow, mainly of the distal small vessels, however, it can also occur secondary to the decrease in venous flow and blood hyperviscosity.9,10 (Table 1).

Etiology of the blue finger syndrome.

| Causes of the blue finger syndrome | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Decreased arterial blood flow | ||||

| Embolism | Thrombosis | Vasoconstriction | Affection of the vascular wall | Other obstructions |

| Atheroembolism or cholesterol | Antiphospholipid syndrome | Acrocyanosis | Vasculitis: | Calcific vasculopathy: |

| Originated in aneurysms | Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome | Perniosis | Buerguer's disease, polyarteritis nodosa,Behçet's disease, thromboangiitis obliterans | calciphylaxis |

| Atrial myxoma | Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura | Chiblain lupus erythematosus (Lupus pernio) | Rheumatoid vasculitis | |

| Intimal angiosarcoma of the aorta | Disseminated intravascular coagulation | Familial chiblain lupus erythematosus or Aicardi-Goutières syndrome | Scleroderma | |

| Infectious endocarditis | Skin necrosis due to anticoagulants | Ergotism and drugs that cause vasoconstriction | Mixed cryoglobulinemia | |

| Marantic endocarditis | Systemic lupus erythematosus | |||

| Hypothenar hammer syndrome | ||||

| Infectious inflammation: syphilis, purulent infections | ||||

| Decreased venous return | ||||

| Extensive venous thrombosis of the iliofemoral sector | ||||

| Phlegmasia cerulea dolens | ||||

| Venous gangrene | ||||

| Blood hyperviscosity | ||||

| Cryoglobulinemia | ||||

| Monoclonal gammopathies (Waldenström macroglobulinemia) | ||||

| Myeloproliferative syndromes: polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia | ||||

| Cold agglutinins (cryofibrinogenemia) | ||||

Adapted from Hirschmann and Raugi.3

The clinical history must be meticulous and include the relationship with the cold (suspecting Raynaud's phenomenon, perniosis, acrocyanosis), the antecedents of vascular procedures or interventions (limb ischemia is reported among the complications of catheterization), changes in medications, consumption of substances (drugs and substances of abuse can be potent vasoconstrictors), previous thromboses and obstetric history (such as screening for hypercoagulable syndromes), presence of constitutional symptoms or malignancy (septic embolisms or paraneoplastic syndromes).11,12

The physical examination focuses on the search for fever, heart murmurs (endocarditis), livedo reticularis (autoimmunity), evaluation of the retina and a complete examination that includes the organs most frequent affected by neoplastic disease depending on age and gender (breast, gynecological, colon, lung, prostate).13–15

There is no prescription for studies that should be recommended for these patients from the beginning, however, it is prudent to include in the routine paraclinical tests a complete blood chemistry, urinalysis (looking for eosinophilia in atheroembolism) and other additional studies depending on the diagnostic suspicion. In general, it is recommended, unless the etiology is obvious, to perform a serology of hepatitis (especially for virus C) and VDRL to rule out infectious causes (including cultures if endocarditis is suspected), cryoglobulins, cold agglutinins and cryofibrinogenemia if there is a relationship with areas exposed to cold, antinuclear antibodies and antiphospholipid profile as autoimmunity screening.2,3,16–19

Imaging studies should always be directed to rule out thrombosis of the arteries that irrigate the affected segment20; they also can help to evaluate other comorbidities. The echocardiogram will be indicated when endocarditis or cardiac tumors are suspected. Radiological or tomographic studies will be used to determine the presence of neoplasms according to the patient context.15

Due to the great clinical variability in the patients and the multiple possible etiologies we recommend a sequential and orderly evaluation distributing the patients depending on whether or not their symptoms are related to the cold (Fig. 4).

Diagnostic algorythm.

Modified from Brown et al.2

The importance of the BFS lies in the fact that it is more than a just a clinical sign, since it is rather an alert of the presence of diseases with high potential harmful for patients, so the recognition and study of the BFS constitutes a challenge in the art of medicine, requiring a complete knowledge on the subject to allow a correct diagnostic and therapeutic approach, in order to avoid comorbidity and, in some cases, mortality in patients.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare we do not have any conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Izquierdo VP, Aguirre HD, Agudelo N, Cuervo FM, Peñaranda E. Reporte de casos de síndrome de dedo azul. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2018;25:292–297.