Osteoporosis is a public health problem. However, there is still a lack of data in Colombia on the characteristics of patients with osteoporosis.

ObjectivesThis study aims to characterise the population with osteoporosis without previous diagnosis.

Materials and methodsObservational, retrospective, descriptive study in patients with osteoporosis. Patients diagnosed between 2014 and 2017 were included. The information was obtained from the patient medical records and the densitometry results.

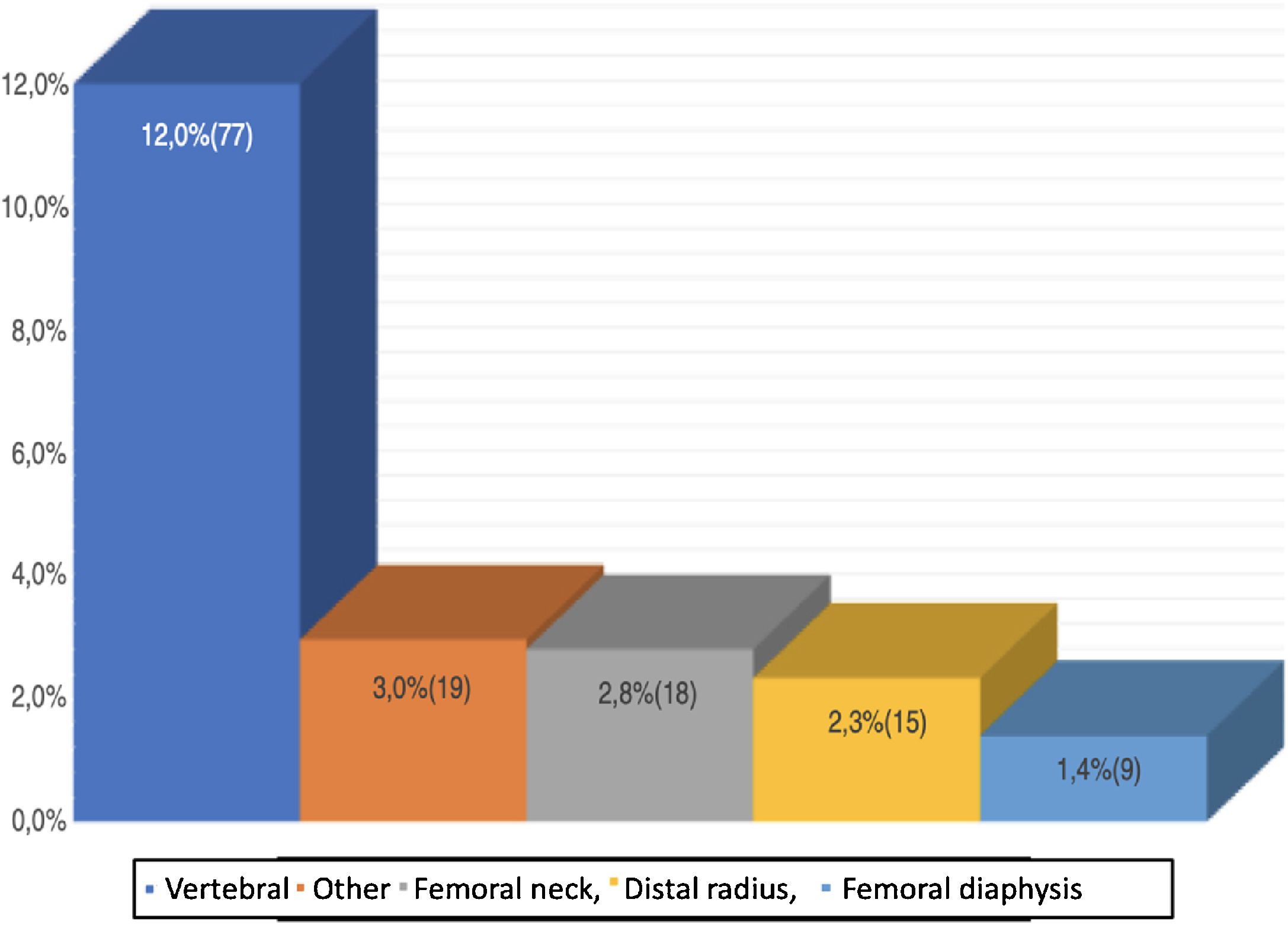

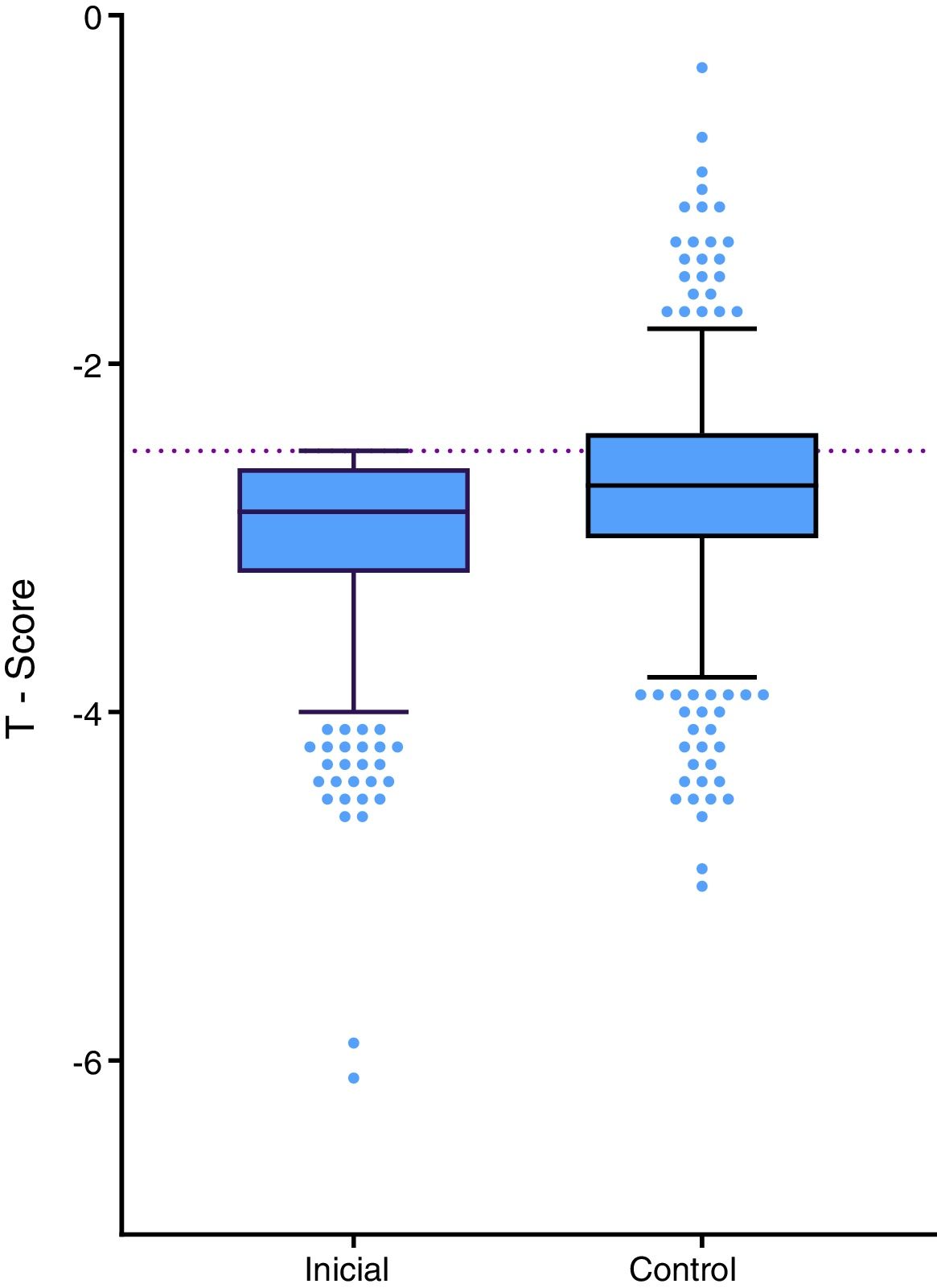

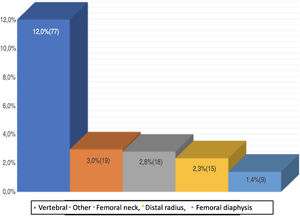

ResultsMost (92.2%) of the patients came from Medellín, and the rest from Cali. The mean age of the population was 65.1 years (SD: 9.97). As regards the history of fracture, it was reported that 12.0% had suffered from vertebral fractures, 2.3% had a history of fracture in the distal radius, 2.8% in the femoral neck, and 1.4% had had femoral shaft fracture. Bone densitometry showed a mean T-score of −2.90 in the femoral neck; −3.02 in total hip; −3.03 in the lumbar spine, and −3.42 in the 33% radius. In the 602 patients who had a control bone densitometry, an average BMD gain was seen in all the evaluated regions.

ConclusionsThe present study has enabled the characterising of patients from 2 Colombian cities with a diagnosis of osteoporosis. The 2 most frequently reported locations for the diagnosis of osteoporosis were lumbar spine and femoral neck. An average BMD gain was also observed.

La osteoporosis es un problema de salud pública, sin embargo, en Colombia en la actualidad faltan datos sobre las características de los pacientes con esta enfermedad.

ObjetivosEste estudio pretende caracterizar la población con osteoporosis sin diagnóstico previo.

Materiales y métodosEstudio observacional, retrospectivo, descriptivo en pacientes con osteoporosis. Incluyó a pacientes diagnosticados entre el 2014 y el 2017. La información fue obtenida a partir de las historias clínicas de los pacientes y el resultado de la densitometría.

ResultadosEl 92,2% de los pacientes provenía de Medellín y los restantes de Cali. La edad promedio ± desviación estándar de la población fue 65,1 ± 9,97 años. En cuanto al antecedente de fractura, se reportó que el 12,0% había presentado fracturas vertebrales, el 2,3% tenía antecedente de fractura en radio distal, el 2,8% en cuello femoral y el 1,4% había tenido fractura de diáfisis femoral. La densitometría ósea (DMO) mostró un T-score promedio de –2,90 en cuello femoral, –3,02 en cadera total, –3,03 en columna lumbar y –3,42 en radio 33%. En los 602 pacientes que contaban con DMO de control se vio una ganancia de la DMO promedio en todas las regiones evaluadas.

ConclusionesEl presente estudio permitió caracterizar a pacientes con diagnóstico de osteoporosis en 2 ciudades de Colombia. Las 2 localizaciones más reportadas para el diagnóstico de osteoporosis fueron columna lumbar y cuello femoral; adicionalmente, se observó una ganancia de la DMO promedio.

Osteoporosis is a systemic disease characterized by a reduction in bone mass, altered bone tissue architecture and increased frailty making patients more susceptible to fractures. The methods used for diagnosing osteoporosis include Bone Mineral Density (BMD) measured using densitometry (bone scan), with ≤−2.5 standard deviations being indicative of osteoporosis1.

This condition is considered a public health issue due to the associated disability and high costs2. In the United States, at least 28 million people have or at least exhibit a high risk of developing osteoporosis3. Studies conducted in Colombia report a prevalence between 11.4 and 32%, depending on the population and affectation. It is estimated that more than 2 million Colombians will have osteoporosis by 20504.

Osteoporosis is considered a “silent disease” because it doesn’t show any symptoms until a fracture develops. The most frequent fracture localizations due to this disease are the vertebrae, the wrists and the hips5. Hip and vertebral fractures are associated with a higher risk of death: between 17 and 37% of the people with a hip fracture die during the course of one year after the fracture6.

Women are considered a population at risk for osteoporosis after menopause, when the negative balance between bone formation and bone resorption accelerates. Additionally, there is a reduction in cortical thickness, in the number of trabecula and increased cortical porosity3. These changes are associated with estrogen deficiency and age2.

Osteoporosis is the most prevalent disease in postmenopausal women7. Although it is less common in males who exhibit a lower risk of osteoporotic fractures, men have a higher mortality following a hip fracture and during hospitalization, as compared to women8.

The treatment of this disease includes life style changes to reduce bone loss, calcium supplementation, Vitamin D and pharmacological agents. The pharmacological strategies for improving BMD, bone quality, or to reduce the risk of fractures, include bisphosphonates, RANK-L inhibitors, parathyroid hormone analogues, inter alia9.

A better understanding of the disease is required to mitigate the public health impact. Currently in Colombia there is a shortage of data on the demographic, clinical and treatment characteristics, and the frequency of fractures in patients with osteoporosis. Therefore, this study is intended to do a demographic, clinical and paraclinical characterization of a previously undiagnosed population with osteoporosis in 2 referral centers in two different cities in the country.

MethodologyObservational, retrospective, descriptive study in patients with osteoporosis. The study included patients diagnosed with osteoporosis for the first time using bone densitometry, between January 1st, 2014 and December 31st, 2017, with complete medical records meeting the selection criteria and excluding potential secondary causes. The total population expected was approximately 650 patients, without doing a formal calculation of the size of the sample. 2 Medical referral centers in Medellin and Cali were included, using a competitive recruitment approach, with no expectation for balanced enrolment of the 2 centers.

Patients in whom osteoporosis could be considered secondary to other conditions were excluded; i.e., malabsorption syndromes, hypogonadal conditions, androgen insensitivity, severe eating disorders, hyperprolactinemia, panhypopituitarism, early menopause, Turner, syndrome, Klinefelter syndrome, acromegalia, adrenal insufficiency, Cushing’s disease, diabetes mellitus type 1, primary or secondary hyperparathyroidism, hyperthyroidism, severe nutritional deficiencies (calcium, magnesium, vitamin D), celiac disease, gastrectomy, inflammatory bower disease, primary biliary cirrhosis, severe liver disease, exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, hemochromatosis, hypophosphatasia, osteogenesis imperfecta, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, Marfan’s syndrome, Menkes’ syndrome, Riley-Day syndrome, porphyria, multiple myeloma, leukemias and lymphomas, systemic mastocytosis, pernicious anemia, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, cystic fibrosis, end-stage kidney disease, idiopathic hypercalciuria, multiple sclerosis and parenteral nutrition.

The information was obtained based on the patients’ medical records and the results of the diagnostic bone scan for osteoporosis. The information on the demographic characteristics, and pathological history organized according to SOC (system organ classes) was compiled, according to the MedDRA classification; smoking, alcohol abuse, a history of fractures in patients with osteoporosis without differentiating between fragility or trauma-associated fractures; medications used for osteoporosis and adverse events reported based on the MedDRA classification. The severity of the fracture was classified in accordance with the researchers criteria. The densitometry for diagnosing osteoporosis and vitamin D levels, calcium and creatinine were also considered.

A descriptive analysis of the sociodemographic and clinical variables was conducted, including a population background analysis. The statistical analysis was done using the Stata Statistical Software: Release 14 (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP).

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Coordinating Center (CAIMED, Bogotá, Colombia, Protocol v. 3.0, October 2019), as well as by the ethrics committees of the participating centers and their investigators, pursuant to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. In accordance with Resolution 008430 of 1993 of the Ministry of Health of Colombia, the study was classified as riskless, since the data was collected from the medical records. An informed consent was considered unnecessary.

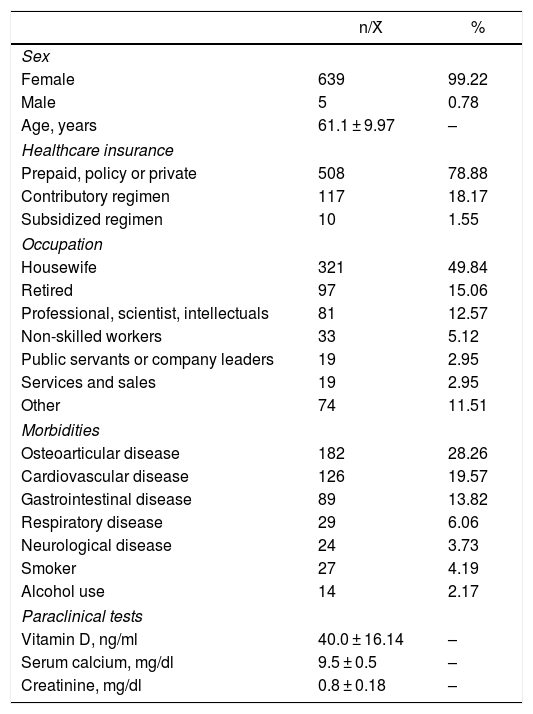

ResultsA total of 3500 medical records of potential patients were analyzed, of which 644 met the selection criteria. The patients came from 2 cities in Colombia: 92.2% were from Medellín and the rest from Cali. The mean age ± standard deviation (SD) of the population was 65.1 ± 9.97 years, and most of them were females (99.2%). With regards to occupation, 49.8% were housewives, 15.2% were retired and 12.6% were professionals (Table 1).

Description of the population.

| n/X̄ | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Female | 639 | 99.22 |

| Male | 5 | 0.78 |

| Age, years | 61.1 ± 9.97 | – |

| Healthcare insurance | ||

| Prepaid, policy or private | 508 | 78.88 |

| Contributory regimen | 117 | 18.17 |

| Subsidized regimen | 10 | 1.55 |

| Occupation | ||

| Housewife | 321 | 49.84 |

| Retired | 97 | 15.06 |

| Professional, scientist, intellectuals | 81 | 12.57 |

| Non-skilled workers | 33 | 5.12 |

| Public servants or company leaders | 19 | 2.95 |

| Services and sales | 19 | 2.95 |

| Other | 74 | 11.51 |

| Morbidities | ||

| Osteoarticular disease | 182 | 28.26 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 126 | 19.57 |

| Gastrointestinal disease | 89 | 13.82 |

| Respiratory disease | 29 | 6.06 |

| Neurological disease | 24 | 3.73 |

| Smoker | 27 | 4.19 |

| Alcohol use | 14 | 2.17 |

| Paraclinical tests | ||

| Vitamin D, ng/ml | 40.0 ± 16.14 | – |

| Serum calcium, mg/dl | 9.5 ± 0.5 | – |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.8 ± 0.18 | – |

Membership to healthcare systems was divided mainly into 3 groups: pre-paid medicine, private insurance policies and subsidized healthcare regimen distributes into 78.9, 18.2 and 1.4%, respectively.

With regards to the history of the population, 4.2% were active smokers and 41.2% said they did not smoke. 2.2% drank alcohol. In terms of family history, 2.7% reported fractures in at least one of their parents.

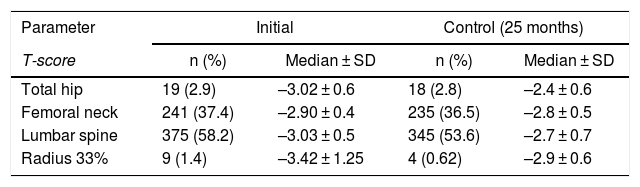

With regards to history of fractures of patients, 12.0% had experienced vertebral fractures classified as mild s (16.9%), moderate (49.4%) and severe (33.8%). The majority had one (39.0%) or 2 (20.8%) affected vertebrae and 16.9% between 3 and 5. The average number of vertebral fractures was 1.9 ± 1.14. 2.3% of the patients had a history of distal radius fracture and 2.8% femur neck fracture. 1.4% of the patients had sustained a fracture of the femoral diaphysis. Of this group, 88.9% was proximal and 11.1% distal. Additionally, 3.0% of the patients with osteoporosis presented with fractures in other sites such as: humerus, (57.1%), rib (19.0%), ankle (14.3%) or wrist (9.5%). Two patients (10.5%) reported 2 fractures each (humerus – rib and humerus – wrist) (Fig. 1).

The most frequent pathological history included osteoarticular (28.3%), cardiovascular (19.6%) and gastrointestinal (13.8%) disease. In contrast, respiratory disease (6.1%) and neurological conditions (3.7%) were the least frequent. Additionally, other preexisting conditions were considered, such as hypertension, hypothyroidism, dislipidemia, rheumatoid arthritis, breast cancer and diabetes mellitus type 2, with frequencies among the population of 13.2, 13.2, 7.9, 4.7, 3.4 and 3.3%, respectively.

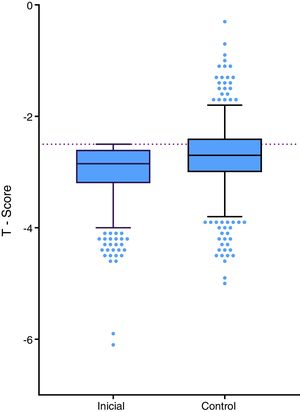

The patients in the study were diagnosed using bone densitometry which resulted in an average T-score of –2.90 SD in the femoral neck,–3.02 SD in total hip, –3.03 SD in the lumbar spine and –3.42 SD in the radius. Of the above-mentioned localizations, the most frequently reported in the medical record were: lumbar spine, femoral neck, total hip and radius with 58.2, 37.4, 2.9 and 1.4%, respectively. The 602 patients who had a control bone scan, an average BMD gain was observed in all the sites assessed (Table 2, Fig. 2). The control densitometries were taken in average after 25 months (interquartile range: 16–36.2).

Bone densitometry T-score.

| Parameter | Initial | Control (25 months) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-score | n (%) | Median ± SD | n (%) | Median ± SD |

| Total hip | 19 (2.9) | –3.02 ± 0.6 | 18 (2.8) | –2.4 ± 0.6 |

| Femoral neck | 241 (37.4) | –2.90 ± 0.4 | 235 (36.5) | –2.8 ± 0.5 |

| Lumbar spine | 375 (58.2) | –3.03 ± 0.5 | 345 (53.6) | –2.7 ± 0.7 |

| Radius 33% | 9 (1.4) | –3.42 ± 1.25 | 4 (0.62) | –2.9 ± 0.6 |

Initial control.

2.3% of the population presented with vitamin D deficiency. The laboratory tests of the patients showed average vitamin D levels of 40.0 ± 16.14 ng/ml, average serum calcium of 9.5 ± 0.50 mg/dl and average creatinine of 0.8 ± 0.18 mg/dl.

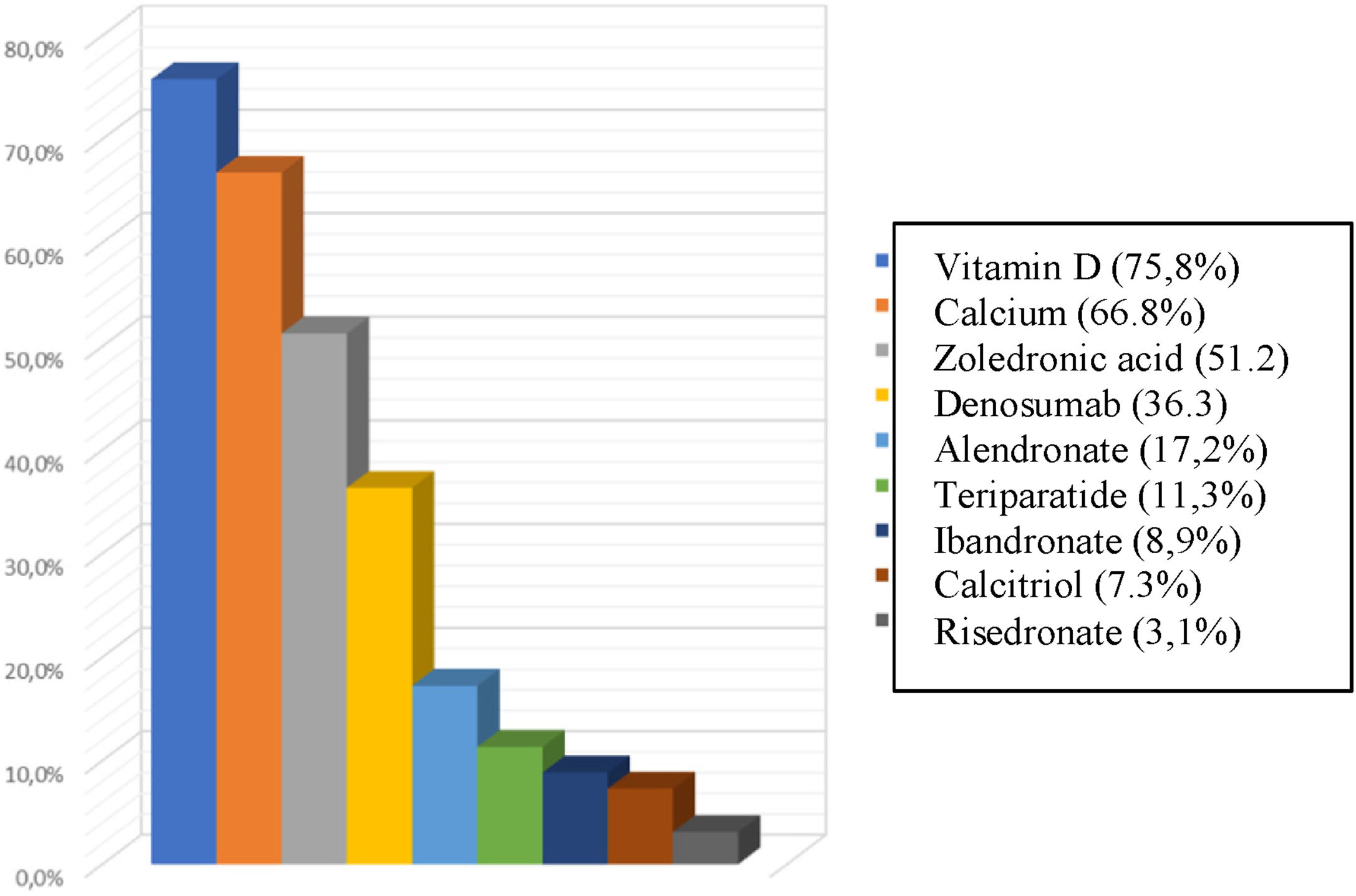

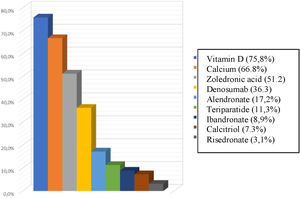

The most frequently used treatments for osteoporosis were zoledronic acid and denosumab in 51.2 and 36.3%, respectively. In terms of supplementation, 75.8% of the subjects had vitamin D as part of their management and 668% calcium (Fig. 3).

With regards to the male population in the study (0.8%), 20% came from Cali and 80% from Medellín. The average BMD measured with an initial T-score was –3.02 SD ± 0.56 and the control densitometry reported a BMD of –2.68 SD ± 0.70. One of the patients in this group showed a history of rib fracture (20%). The treatment most frequently used in males was zoledronic acid (60%), followed by calcitriol (40%) and calcium carbonate (40%). Other therapies such as alendronate, teriparatide and denosumab had a frequency of 20% each in males.

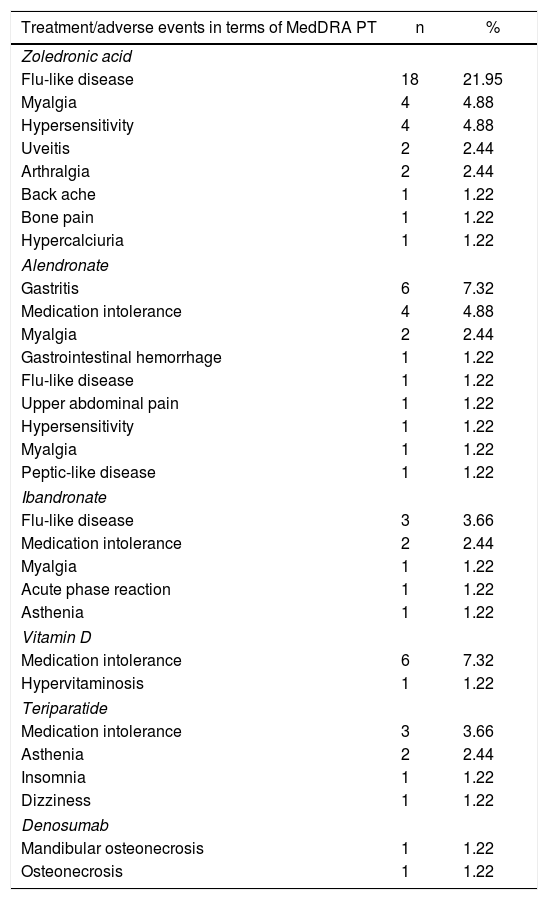

Finally, of the treatments or supplements used, the ones which reported adverse events more frequently were zoledronic acid (40.3%), followed by alendronate (22.0%), ibandronate (9.8%), vitamin D (8.5%) and teriparatide (8.5%) (Table 3). Treatment options such as calcium, risedronate or denosumab showed less than 2.5% of adverse events each.

Osteoporosis treatment-associated Adverse events in terms of MedDRA Pt.

| Treatment/adverse events in terms of MedDRA PT | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Zoledronic acid | ||

| Flu-like disease | 18 | 21.95 |

| Myalgia | 4 | 4.88 |

| Hypersensitivity | 4 | 4.88 |

| Uveitis | 2 | 2.44 |

| Arthralgia | 2 | 2.44 |

| Back ache | 1 | 1.22 |

| Bone pain | 1 | 1.22 |

| Hypercalciuria | 1 | 1.22 |

| Alendronate | ||

| Gastritis | 6 | 7.32 |

| Medication intolerance | 4 | 4.88 |

| Myalgia | 2 | 2.44 |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 1 | 1.22 |

| Flu-like disease | 1 | 1.22 |

| Upper abdominal pain | 1 | 1.22 |

| Hypersensitivity | 1 | 1.22 |

| Myalgia | 1 | 1.22 |

| Peptic-like disease | 1 | 1.22 |

| Ibandronate | ||

| Flu-like disease | 3 | 3.66 |

| Medication intolerance | 2 | 2.44 |

| Myalgia | 1 | 1.22 |

| Acute phase reaction | 1 | 1.22 |

| Asthenia | 1 | 1.22 |

| Vitamin D | ||

| Medication intolerance | 6 | 7.32 |

| Hypervitaminosis | 1 | 1.22 |

| Teriparatide | ||

| Medication intolerance | 3 | 3.66 |

| Asthenia | 2 | 2.44 |

| Insomnia | 1 | 1.22 |

| Dizziness | 1 | 1.22 |

| Denosumab | ||

| Mandibular osteonecrosis | 1 | 1.22 |

| Osteonecrosis | 1 | 1.22 |

In terms of the demographic characteristic, age is consistent with other studies conducted in Colombia, in which the patients with osteoporosis are in their 70 s10. It is worth noting the high percentage of females in our study – over 99% of the population – considering that in other studies with Colombian population, the percentage of females has been reported at 75.6–95.0% of the patients with osteoporosis10–12.

In terms of insurance, our study showed that around 2 of every 10 patients seek healthcare via the contributory regimen; this was a lower percentage as compared to a study conducted in Bogotá, in which 59.7% were contributory regimen10. This may be due to the fact that most of the patients in our population came from private consultation of a referral medical center, probably because these are users of pre-paid insurance policies or private patients.

With regards to patients’ habits, the data are similar to what has been reported in other studies11–13, which show that 5% of the population with osteoporosis are smokers and 2% are alcohol users. In our study, the prevalence of smokers was 0.8% lower and the frequency of alcohol users 0.2% higher.

It has been found that a history of fracture in parents is one of the risk factors of developing osteoporotic fractures14. Our study showed that 2.7% of the population had at least one parent with a history of fracture, which contrasts with the findings in other studies conducted in the country, in patients with osteoporotic fractures, since those studies showed that 1% had a first-grade relative with a history of fractures15. The study by Fernández-Ávila et al.15 also showed that the most frequent osteoporotic fractures are femoral neck fractures (51.4%), vertebral fractures (23.4%), wrist fractures (22.5%) and humerus fractures (4.5%) which contrasts with our study which showed a higher frequency of vertebral fractures, femoral neck, and wrist (Fig. 1). However, this difference in frequencies may be attributed to the characteristics of the populations and also to the fact that the study by Fernández-Ávila et al. was in patients who visited the doctor’s office due to fractures, contrary to our study in which the findings could have been incidental.

Due to the age of the patients with osteoporosis, our study evidenced that diseases such as hypertension, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes mellitus type 2 had a prevalence ranging between 3.3 and 13.2%, which was lower than the prevalence evidenced in a study assessing some characteristics in patients with postmenopausal osteoporosis, in a real world environment in which the diseases had a prevalence 2 to 6 times higher than the prevalence reported in our patients13.

Bisphosphonates are considered part of the first line therapies for the initial management of patients with osteoporosis. This study showed that bisphosphonates such as zoledronic acid are used in over 50% of the patients, reflecting what has been reported in other studies in Colombia, showing that bisphosphonates are the most frequently used medications2,10,13. It should be noted that in our study, over 75% of the patients used vitamin D as part of their medical management, while other studies showed that 29.6% used vitamin D supplementation. Likewise, calcium supplementation in our study was 55.3% higher that the numbers reported in other studies (43%)13.

Notwithstanding the fact that the densitometry diagnosis of osteoporosis is based on a bone scan BMD of ≤–2.5 SD, in which the measurement of the radius is used for diagnosis in particular situations1, the preferred site may be different. In our study, more than 95% of the population used the lumbar spine (58.2%) and femoral neck (37.4%) as a reference to make the densitometry diagnosis of osteoporosis; this is consistent with the findings in other studies in which the lumbar spine (49.7%) and the femoral neck (36.8%) were the most widely used diagnostic sites13.

With regards to the BMD of the above-mentioned sites, our study showed a higher lumbar spine BMD of 0.07 g/cm2, as compared to the study by Cunha-Borges et al. (–3.10)13. In contrast, the femoral neck BMD showed a value of –0.50 SD, lower than the report from the ALAFOS trial (–2.40)13.

Finally, of the laboratory parameters assessed in this study, vitamin D levels were higher (1.8 higher) than the average reported in similar populations (22.6 ± 6.38 ng/ml)16. This corelates with a higher vitamin D supplementation of the patients in this study. Moreover, the calcium levels in our population were similar to the findings in patients from an intermediate city in Colombia (9.08 ± 0.76 mg/dl)16.

Considering that this was a retrospective, real world study, the secondary nature of the information also may account for the proportion of lost data, as compared against other types of design. This study showed that the non-available information was in average 19.9%. The main limitation to establish a comparison of the control bone scan results is the non-availability of the technical features of the densitometers.

Furthermore, most patients came from a referral medical center, mostly from private consultation or insurance policies, accounting for a selection bias. All in all, these limitations prevent us from extrapolating the results to the general Colombian population. Similarly, currently there are no studies in Colombia characterizing patients with osteoporosis, with similar selection criteria to the patients herein, which limits inter-study comparisons.

ConclusionThis study enabled the characterization of patients with a diagnosis of osteoporosis in 2 referral centers in 2 major cities in Colombia, although the results cannot be extrapolated to the general population. The high percentage of females and housewives should be highlighted. The 2 most frequent sites reported for the diagnosis of osteoporosis were the lumbar spine and the femoral neck, with a T-score of –3.03 SD and –2,90 SD, respectively. The most commonly reported fracture site was the spine. The treatments used more often were zoledronic acid and denosumab.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Please cite this article as: Molina JF, Toro CE, Reynales Londoño H, Hernandez N. Caracterización clínica y demográfica de la población con osteoporosis en 2 centros médicos de referencia en Colombia. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2021;28:282–288.