To contextualize a medical prescription of the early 19th century in the New Kingdom of Granada, in which guaco was prescribed to reduce symptoms caused by musculoskeletal system disorders, which were ill-defined at the time. Similarly, based on current knowledge, to analyse the manner in which the formula acts on pathophysiological mechanisms of rheumatic diseases, in order to explain the reduction of pain, and associated sequelae.

Materials and methodsDocumentary research into the Cipriano Rodríguez Santamaría Historical Archive of the Octavio Arizmendi Library of the University of La Sabana, in Chía, Colombia. The document analysed was called "Rheumatism". Subsequently, a review of the literature was carried out in Science Direct / Clinical Key / Scielo databases in the period from 1999 to 2018.

ConclusionsThere is scientific evidence that supports the efficiency of guaco used in the Kingdom of New Granada due its anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties. However, a vague description of the dosage of the guaco, signs, symptoms, and comorbidities, which are not mentioned in the prescription, hinders the understanding of its application and the thorough effectiveness of the treatment in order to control the symptoms of musculoskeletal system conditions. This tradition, consequently, lacks proper scientific support for the medical treatment of musculoskeletal disorders.

Contextualizar una receta médica de comienzos del siglo XIX en el Nuevo Reino de Granada, en la cual se prescribe el guaco para disminuir síntomas generados por afecciones del sistema músculo-esquelético. De igual forma, analizar con base en conocimientos actuales, cómo actúa la fórmula sobre mecanismos fisiopatológicos de la enfermedad, explicando la reducción del dolor y las secuelas asociadas.

Material y métodoBúsqueda documental en el Archivo Histórico Cipriano Rodríguez Santamaría, de la Biblioteca Octavio Arizmendi Posada, de la Universidad de La Sabana. Se analizó el documento denominado “Reumatismo”. Posteriormente se realizó una revisión de la literatura entre 1999–2018, en las bases de datos ScienceDirect/ClinicalKey/Scielo.

ConclusionesExiste evidencia científica que podría explicar la efectividad del guaco, usado en el Nuevo Reino de Granada por sus propiedades antiinflamatorias y analgésicas aportadas por componentes como la cumarina y los flavonoides. Sin embargo, una descripción vaga en la posología del guaco, signos, síntomas y comorbilidades, que no se mencionan en la receta, dificulta analizar la eficacia del tratamiento y cómo lograba disminuir o controlar específicamente los síntomas dados por afecciones del sistema músculoesquelético con su aplicación. Esta tradición, en consecuencia, carece de sustento propiamente científico para el tratamiento médico de patologías osteomusculares.

The Cipriano Rodríguez Santa María Historical Archives, of the Universidad de La Sabana, have multiple medical prescriptions from the late 18th Century and early 19th Century, including a prescription describing breakthroughs and medical practices in Colombia over more than two centuries ago. The prescription was used for the treatment of disabling musculoskeletal conditions. This paper is intended to help us understand the scientific and cultural foundations supporting these relatively successful therapies, used during this period in history.

Journey of medicine and rheumatology over timeThe relationship between human diseases and the attempt by mankind to fight such diseases using traditional medicine, has been established over time. Alcmaeon of Crotona, philosopher and follower of Pythagoras around the year 500 B.C., defined health and disease as: «What preserves health is a balance between opposite qualities: dry and wet, cold and hot, bitter and sweet, etc. If any of those qualities prevails over the other, then disease develops… Diseases arise from the predominance of one of the qualities and also from poor nutrition or other externalities, such as rain, place of residence, fatigue, anxiety, and similar factors. Health depends on the combination of all qualities and external factors in the right proportions».1 With regards to rheumatic diseases, the first references were made by the father of western medicine, Hippocrates de Cos (460−370 BC), who used in his writings the word «rheuma», and is also associated with traditional medicine such as herbal and homeopathic medicine.2 Cornelius Celsus (26 BC.-50 AC.) refers to the word rheuma as a process of pain and inflammation (rubor et tumor, cum calore et dolore).3 Thomas Sydenham (1624–1689), an English physician, described in the 18th Century the semiology, the clinical manifestations and risk factors for gout, a disease he apparently suffered from.4 François Raspail (1794–1878), French physician, chemist, philosopher, and botanist, in his book Manual for health with domestic medicine and pharmacy, associates sedentarism and alcohol abuse with rheumatic diseases.5 Sir Marc Armand Ruffer (1859–1917), physician, pathologist, focused on paleopathology, anthropology, history, ethnography, and geography in different regions around the world, primarily in Egypt, investigating diseases of the bones, joints and muscles in mummies; he associated ancient discoveries with modern technology such as molecular biology, immunology, mitochondrial DNA, and techniques capable of tracing the origin and history of rheumatological diseases.3

The beginning of rheumatology in the New Kingdom of GranadaTo speak about medicine during the colonial times involved associating a number of empirical and scientific knowledge brought from Europe, Asia and even from Africa, with the knowledge characteristic of rituals of slaves. The prescription described by William White (c. 1764–1834), a British merchant friend of Simón Bolívar (1783–1830), who died in Caracas 4 years after the death of the Liberator in Santa Marta, was mostly influenced by Spanish knowledge. It is believed that the medical literature of that time was based on the Spanish Pharmacopeia and the Pharmacopeia Matritensis, brought from the Iberian Peninsula late in the 18th Century; these are jewels of the literature because of the limited number of copies and their treasured educational content. Spanish apothecaries resident in America mastered the art of medicine to such degree, that they even published similar books that then became indispensable for the training of American apothecaries. The shortage of apothecaries in the New Kingdom of Granada, in addition to insalubrity and epidemics, demanded a lot of courage from practitioners. The therapeutic techniques were transmitted through the oral tradition (folk medicine), mostly among members of religious communities such as Saint John of God; they were the only ones with the financial and hierarchical power to embrace medical knowledge. As time passed, a secular movement developed aimed at training apothecaries, a trade which was then practiced by an individual in a dispensary of herbal medicines called apothecary’s shop. According to the evidence, Antonio Gorraez was one of the first lay apothecaries established in Santafé. His apothecary shop was the first to open in Santafé, with the help of a rich merchant.6 So the apothecary, or the physician, was in charge of prescribing herbal medicines, and monitoring the evolution and effectiveness in improving the symptoms.

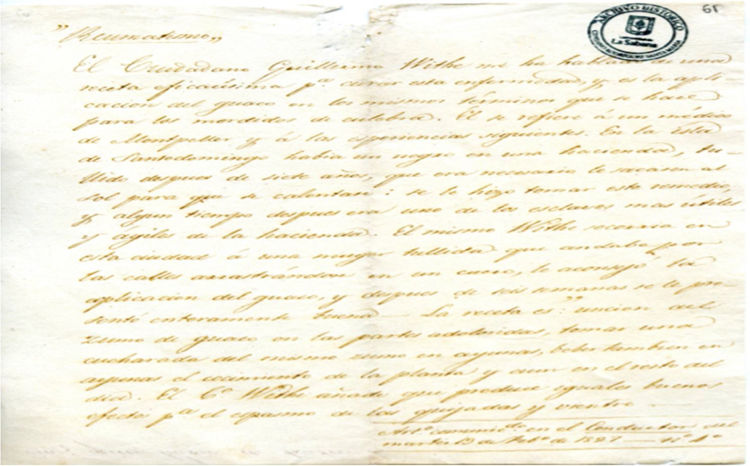

Following is a quote from the source document:

«Citizen Guillermo Withe has mentioned a very effective prescription to cure this disease, based on the use of guaco, in the same manner as it is used for snakebites. Mr. Withe speaks about a physician from Montpellier who had the following experiences: There was a black man in a farm in the isle of Santodomingo who had been crippled for seven years and he had to be taken out under the sun to warm him up; the man was given this medicine and after some time he became one of the most helpful and skillful slaves in the farm. Mr. Withe also took care of a crippled woman who crawled along the streets siting on a piece of cowhide; he advised her to take guaco, and six weeks later, the woman came to see him fully recovered. The prescription indicated to rub the guaco juice on the affected areas, take one spoon of the same juice before breakfast, drink the plant infusion also before breakfast and several times during the day. Mr. Withe also claims that this remedy is equally beneficial for jawbone and abdominal spasms» (Fig. 1).

Prescription for rheumatism.

Source: Cipriano Rodríguez Santamaría History Archives, Octavio Arizmendi Posada Library, Universidad de La Sabana.

Reference: Archivo Histórico Cipriano Rodríguez Santamaría. Biblioteca Octavio Arizmendi Posada, Universidad de La Sabana. Caja 10, carpeta 2 (parte 2. PDF), f. 61 r. Available at: https://intellectum.unisabana.edu.co/handle/10818/18140, part 2.PDF.

The most frequent rheumatological diseases in Colombia are osteoarthritis, low back pain, fibromyalgia, Sjögren’s syndrome, SLE, dermatomyositis, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and gout.7 Rheumatoid arthritis and gout are probably the conditions that affected the patient described by Mr. Withe, but the lack of data and definitions about this type of diseases at that time, make it difficult to determine exactly what was the disease of the patient discussed in this document.8

Guaco, a front-line therapy in the late 18th century and early 19th centuryThe medicinal use of raw herbs is most common in developing or underdeveloped countries, due to economic, cultural, spiritual and demographic factors. Mikania glomerata and Mikania laevigata are 2 species commonly referred to as guaco; these are climbing plants from the Asteraceae family, which are morphologically similar and are native of the Southeastern part of Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Paraguay. Its use in physical therapy has been documented for over 200 years and has been known by the nickname “snake herb” because it is widely used for snakebites, as a topical agent, due to is anti-inflammatory properties.9 A search of the chemical components of guaco in the medical, botanical and biological literature, confirms its use and effects in the pathophysiological processes of a long list of diseases, and specifically its effective anti-inflammatory and analgesic properties in musculoskeletal illnesses. Its principal components are coumarin and flavonoids. Coumarin belongs to the benzodiazepines family and is responsible for 50-60% of the analgesic and anti-inflammatory activity,10 particularly of M. laevigata, which evidenced a higher coumarin concentration versus M. glomerata. Moreover, it plays a useful role as a raw material used in the manufacturing of perfumes, detergents, toothpaste, cigarettes, alcohol, gums, plastics, paints, sprays, sweeteners, and supplements in essential oils and antimicrobial agents.11 Flavonoids, on the other hand, have anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and antioxidant properties associated with the inhibition of acute phase interleukins (IL-1, IL-6), and of various enzymes such as cyclooxygenase, lipoxygenase, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, oxidase and xanthine oxidase.12 Therefore, coumarin has an anti-inflammatory effect in Mikania, particularly in the M. laevigata species, more than in M. glomerata, and should be differentiated for research purposes.13

A special case regarding the use of guaco as the “snake herb” was during the Spanish botanical expeditions. These expeditions were led by outstanding personalities such as José Celestino Mutis and encouraged the arrival of other botanists including Alexander von Humboldt and Aimé Bonpland, early in the 19th Century. They were guided by local botanists such as botanist and artist Francisco Javier Matís, who were eager to learn about the wide variety of the flora in the New Granada. Matís, was born in 1763, in Guaduas, from a low-income family and was passionate and talented for drawing plants. Fray Diego García, who had been commissioned by José Celestino Mutis to collect plants, recognized Matís’s talent and appointed him as the official artist for the Royal Botanical Expedition where he served for over 30 years. While collecting, classifying and drawing, Matís became particularly interested in the guaco leaf, and was the first one to identify its antivenom properties, based on the report of an afro-neogrenadin co-worker, - negro Pío – who remained in anonymity.14

Based on this experience, Matís began to practice as a healer and adopted the guaco leaf as an essential therapeutic resource to help people, taking care of patients in different areas which he visited regularly to monitor his patients. When he realized that his productive life was coming to the end, he trained Nicolás Cárdenas as a healer to continue his legacy. Matís died at 88 years old and it has been said that he was unable to personally follow on his last patient treated with guaco and who survived thanks to the effectiveness of the plant. There is no doubt that Matís revolutionized herbal medicine with the use of the guaco leaf. Guaco became a legendary plant in the transition from the 18th to the 19th Century in the New Kingdom of Granada to the new Colombia.

Evolution in the symptomatic management of rheumatologyThe current management of acute pain in rheumatic disease is mainly based on non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs, that have a similar mechanism of action as guaco. NSAIDs are used in inflammatory, progressive and degenerative diseases because of their analgesic properties via the depletion of inflammatory mediators such as prostaglandins, prostacyclin and thromboxane, inhibiting the cyclooxygenase or prostaglandin-endoperoxide-synthase enzyme based on arachidonic acid. Other therapeutic options are the glucocorticoids that generate an intracellular cytoplasmic signaling cascade in glucocorticoid receptors, that dimerize releasing a second messenger targeted to the nucleus, to be able to modulate gene expression.15

Slowing down the progression of the disease, an objective not previously considered. Most of the non-surgical diseases affecting the locomotor system become chronic and require modern medicine to innovate with treatments for an uncontrolled chronic response of the immune system. The study and in-depth understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms of the rheumatological diseases have resulted in an amazing progress over the last two decades, leading to the development of new therapeutic technologies, with specific treatment targets. Managing these patients now involves much more than simply relieving pain; treatment focuses on clear remission goals, being able to stop the progression of the disease, preventing joint or visceral damage, and disability. The lives of many patients, similar to the description of Mr. Withe, have drastically changed; however, there are still some patients who are refractory to the various treatment options, or who have limitations due to the adverse effects of the new therapies. As a result of gene sequencing, of the development of pharmacogenomics, and the possibility to manage and analyze big data, the 21st Century is the age of precision or personalized medicine.16,17 Just from a therapeutic perspective, for the first time we now face the possibility to deliver specific, personalized, individualized therapies that are light-years ahead of the purely symptomatic approaches to the rheumatological conditions in colonial times.18

ConclusionIn light of the current medical literature, the anti-inflammatory and analgesic characteristics of guaco – particularly due to the presence of coumarin – account for the improvement of symptoms described in Mr. Withe’s prescription. While obviously the scientific foundations we know recognize, and which are supported by science, to diagnose and treat the diseases affecting the locomotor system, were not known in the 18th Century, it is worth noting the merits of delivering a symptomatic treatment, effective to some extent, despite the prevailing limitations at the time. However, the vague information about the dosing and treatment parameters of guaco, make us wonder whether the results obtained in those patients have been garbled by non-modifiable factors, such as genetics or gender; furthermore, in the past, the lack of knowledge about the disease prevented its optimal therapeutic management which was limited to addressing the symptoms. Therefore, this guaco tradition had no scientific support for the medical treatment of osteomuscular disorders.

FinancingThe research and publication were funded by the universities the authors are associated with.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

The authors want to express their gratitude to Marcela Revollo Rueda, director of the Historical Archives of the Octavio Arizmendi Posada library of Universidad de la Sabana, for her generosity and collaboration.

Please cite this article as: Tuta-Quintero E, Uribe-Vergara J, Martínez-Lozano JC, Mora-Karam C, Gómez-Gutiérrez A, Briceño-Balcázar I. El Guaco: un agente vegetal utilizado en el Nuevo Reino de Granada contra los síntomas generados por afecciones del sistema músculo-esquelético. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2021;28:52–56.