Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is a serious complication of several rheumatic disorders, among which are the systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Still’s disease and systemic lupus erythematosus. This syndrome is part of the Acquired Haemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytoses, and is a potentially fatal disease, with difficulty in its identification and a lack of consensus regarding its management. A series of cases are described of patients with macrophage activation syndrome, explaining their diagnostic process, their relationship with rheumatic diseases, their monitoring and treatment, as well as the results of different management schemes.

El síndrome de activación macrofágica (SAM) es una grave complicación de varias entidades reumáticas entre las que se encuentran la artritis idiopática juvenil sistémica, enfermedad de Still y lupus eritematoso sistémico. Este síndrome forma parte de las linfohistiocitosis hemofagocíticas adquiridas y constituye una enfermedad potencialmente mortal, con dificultad en su identificación y carencia de consensos en cuanto a su manejo. Describimos una serie de casos de pacientes con SAM, exponiendo su proceso diagnóstico, su relación con las enfermedades reumáticas de base, su seguimiento y tratamiento, así como los resultados de diferentes esquemas de manejo.

Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) is a potentially fatal condition found in the group of acquired haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. The term MAS is used to refer to the syndrome associated with rheumatological entities, mainly systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, Still's disease and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).1,2 MAS is characterized by being an acute inflammatory process, which occurs with high fever of difficult remission, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathies, hemorrhagic manifestations and dysfunction of the central nervous system, in addition to the alteration of several laboratory tests including pancytopenia, hypofibrinogenemia, hypertriglyceridemia, decreased ESR and hyperferritinemia, as well as the presence of macrophages phagocytizing hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow aspirate and biopsy (BMA).3,4 This syndrome can occur at any age, but it is more common in the fifth decade of life and in women.5,6 It is produced by an abnormal immune response of multifactorial origin, with increased activation of T lymphocytes and macrophages. The inheritance of defective genes involved in the control of cytolysis leads to a cytolytic activity of NK cells; these cells are not able to eliminate the tumor or infected cells, so the proliferation of the population of cytotoxic T-cells induces the activation and proliferation of tissue macrophages (histiocytes), producing a cytokine storm, which leads to a proinflammatory state with increased production of gamma interferon, tumor necrosis factor alpha, IL-1, IL-6 and a decrease in IL-10.7

MAS usually has precipitating factors for its onset, among which we can find exacerbations of the underlying rheumatologic disease, use of medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, bacterial, fungal or viral infections, being the most important the infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), malignancy and transplants.8 We describe a series of cases of patients with MAS, exposing their diagnostic process, their relationship with the underlying rheumatic diseases, their follow-up and treatment, as well as the results of different management schemes.

Case presentationCase 1. A 51-year-old female patient, of mixed race, with a diagnosis of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome meeting clinical criteria: gestational morbidity (fetal death >10 weeks) and submassive pulmonary thromboembolism (V/Q scan) and laboratory criteria (positive IgM anticardiolipin antibodies: 154, positive β-2 glycoprotein 1 IgM: 31.9, positive β-2-glycoprotein 1 IgG: 33.9); secondary to SLE with SLICC 2012 criteria supported by: oral thrush, leukocytopenia/lymphopenia, serositis (bilateral pleural effusion), antinuclear antibodies (ANA): 1/640, anti-DNA: 141.96, complement consumption, renal compromise (proteinuria >500 mg/24 h) and a positive direct Coombs test (without hemolytic anemia). The patient was admitted to the emergency room in June 2017 with fever, oral thrush, dyspnea on medium exertion and Raynaud’s phenomenon. On physical examination, fever of 38.7 °C, Raynaud’s phenomenon and overweight (body mass index: 28.3) were documented. The laboratory studies reported macrocytic anemic syndrome, leukocytopenia, lymphopenia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, elevated ESR, alteration in renal function, elevated transaminases, positive rheumatoid factor, hyperferritinemia, complement consumption, and positive direct Coombs test (Table 1). The BMA described infiltrate of monomorphic cells and immunohistochemistry with a pattern of follicular lymphoma and macrophages phagocytizing hematopoietic cells.

Clinical, serological and treatment characteristics of the patients.

| General | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 51 | 41 | 16 | 25 |

| Sex | Female | Female | Female | Male |

| Rheumatologic disease | APS, SLE | SLE | SLE | Dermatomyositis |

| Criteria | ||||

| Fever | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | No | No | No | Yes |

| Leucocytes, RV: 8000–14,000/μL | 230 | 1360 | 2830 | 450 |

| Hemoglobin, RV: 12–15 g/dL | 8.8 | 6.9 | 8.0 | 7.4 |

| Lymphocytes, RV: 1000–4500/μL | 200 | 600 | 200 | 300 |

| Neutrophils, RV: 3300–10,000/μL | 0 | 700 | 400 | 100 |

| Platelets, RV: 150,000–450,000/μL | 2000 | 1000 | 10,000 | 26,000 |

| ALT, RV: 2–41 U/L | 164 | 158 | 166 | 184 |

| AST, RV: 5–40 U/L | 342 | 261 | 265 | 1326 |

| Ferritin, RV: 20–500 ng/mL | >2000 | >2000 | 1301 | >2000 |

| LDH, RV: 105–333 IU/L | 1385 | 1320 | 289 | 1.794 |

| Triglycerides, RV: <150 mg/dL | 187 | 188 | 189 | 731 |

| Fibrinogen, RV: 200–400 mg/dL | 25 | 51 | 89 | 71 |

| Haemophagocytic cells | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Other laboratories | ||||

| BUN, RV: 9−20 mg/dL | 77 | 38.8 | 15.4 | 18 |

| 0.6–1.2 mg/dL | 2.67 | 0.84 | 0.82 | 0.5 |

| Rheumatoid factor, RV: 15−20 IU/mL | 64 | 62 | <8.0 | <8.0 |

| Urinalysis | Hematuria | Proteinuria/hematuria | Proteinuria/hematuria | Hematuria |

| Treatment | ||||

| Combined therapy | Corticosteroids, rituximab | Corticosteroids, cyclophosphamide | Corticosteroids, immunoglobulin G | Corticosteroids, immunoglobulin G |

| Evolution | ||||

| Complete remission of symptoms | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; APS: antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; RV: reference value.

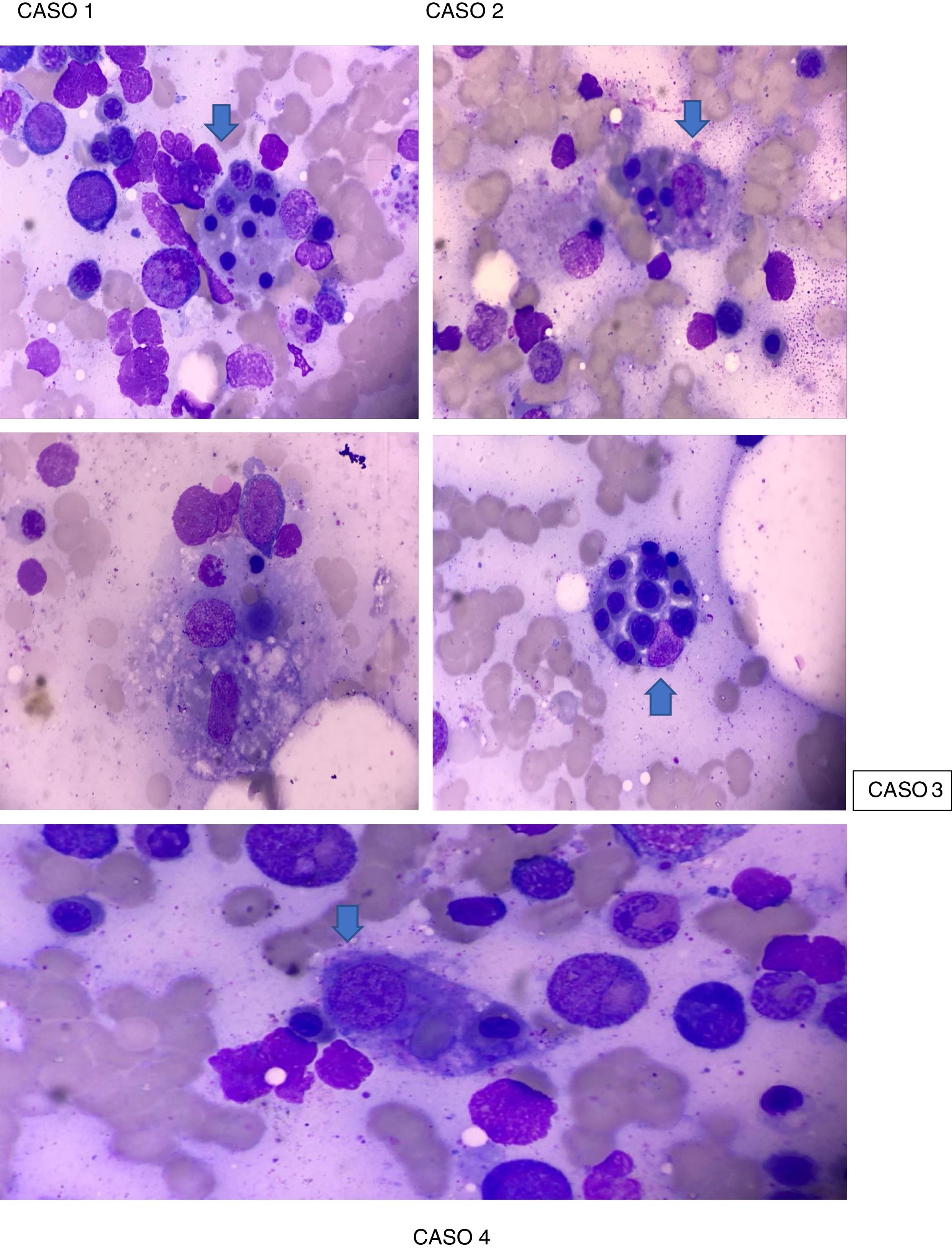

The patient exhibited Parodi criteria for MAS (Table 2), supported by clinical criteria: fever and laboratory criteria: cytopenia in 2 or more cell lines, hemoglobin (Hb) <9.0 g/dL, elevation of transaminases and hyperferritinemia with a BMA which revealed macrophages phagocytizing hematopoietic cells (Fig. 1). Then, she was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), with protective isolation. Pharmacological management was started with pulses of methylprednisolone 500 mg IV for 3 consecutive days followed by oral prednisone at doses of 1 mg/kg/day max, 60 mg/day, hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/day, prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii with trimetoprim/sulfamethoxazole 960 mg 3 times a week, presenting clear improvement, good modulation of her inflammatory response, with negative cultures, decrease in acute-phase reactants and improvement in hematological parameters (except platelets). The administration of rituximab was considered, which showed a considerable rise in the platelet count >100,000/mL after the second dose, without presenting infusion reactions. Given the hemodynamic stability and the compensation of her clinical disease, the patient was discharged from the Rheumatology specialty with an indication of a dose of rituximab in 6 months, subcutaneous fondaparinux 7.5 mg every day and outpatient control by Rheumatology and Hematology.

Parodi diagnostic criteria for macrophage activation syndrome.

| Clinical criteria |

| Fever >38 °C |

| Hepatomegaly (≥3 cm below the costal margin) |

| Splenomegaly (≥3 cm below the costal margin) |

| Hemorrhagic manifestations |

| Dysfunction of the central nervous system |

| Laboratory criteria |

| Cytopenia in 2 or more cell lines (hemoglobin <9.0 g/dL, leukocytes: <4000/μL, platelets: <100,000/μL, neutrophils: <1000/μL) |

| Increased aspartate aminotransferase (>40 units/L) |

| Increased lactate dehydrogenase (>567 units/L) |

| Hypertriglyceridemia >178 mg/dL |

| Hypofibrinogenemia >150 mg/dL |

| Ferritin >500 μL/L |

| Histopathological criterion |

| Evidence of haemophagocytic macrophages in the bone marrow |

Case 2. A 41-year-old female patient, of mixed race, with a diagnosis of SLE, presenting SLICC 2012 criteria, supported by: alopecia, ANA of 1/2560 homogeneous pattern, leukocytopenia/lymphopenia, thrombocytopenia, serositis (pleural effusion), clinical synovitis in hands and knees, positive direct Coombs test, hemolytic anemia, renal compromise (proteinuria >500 mg/24 h), who was admitted in March 2018 due to fever of 2 months of evolution and hemoptysis. On physical examination she presented biphasic Raynaud’s phenomenon in the hands, bilateral livedo reticularis in the feet and discrete generalized rash on the anterior chest. The patient was admitted for hospital management and laboratory tests were performed (Table 1), with which it was found that she met the Parodi criteria for MAS (Table 2), supported by clinical criteria: fever and hemorrhagic manifestations and laboratory criteria: cytopenia in 2 or more cell lines, Hb <9.0 g/dL, increased aspartate aminotransferase >40 and hyperferritinemia, BMA that revealed macrophages phagocytizing hematopoietic cells (Fig. 1). The presence of an infectious focus was not evidenced. A 3-day scheme of methylprednisolone 500 mg was started in combination with a dose of cyclophosphamide 500 mg IV, showing a substantial clinical improvement, which is why oral prednisone at a maintenance dose of 1 mg/kg/day was started, presenting complete remission of symptoms.

Case 3. A 16-year-old female patient of mixed race, with a diagnosis of SLE, presenting 2012 SLICC criteria, supported by skin involvement (malar rash), oral ulcers, non-scarring alopecia, joint manifestations and hematological alterations (leukocytopenia, lymphopenia and severe thrombocytopenia), and laboratory criteria (ANA 1/5120 speckled pattern, anti-DNA 1/80, positive anti-Sm, positive IgM anticardiolipin antibodies and positive direct Coombs test), who was admitted in October 2018 due to a clinical picture of 3 days of evolution, consisting of fever, epistaxis and gingival bleeding associated with periods of disorientation. The patient was admitted to the hospital where laboratory tests were performed (Table 1), finding that she met the Parodi criteria for the diagnosis of MAS (Table 2), supported by: neurological dysfunction, fever and hemorrhagic manifestations, in addition to laboratory criteria that include: severe pancytopenia, severely elevated aspartate aminotransferase, elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), hypofibrinogenemia, hypertriglyceridemia and hyperferritinemia, and BMA that revealed macrophages phagocytizing hematopoietic cells (Fig. 1). Management was started with pulses of methylprednisolone 500 mg IV, during 3 consecutive days, followed by oral prednisone at doses of 1 mg/kg/day max. 60 mg/day in combination with IgG at doses of 2 mg/kg/day for 4 consecutive days and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, presenting a favorable clinical evolution with subsequent remission of symptoms.

Case 4. A 25-year-old white male patient, known by the specialty of Rheumatology due to a clinical picture that began in June 2017 with generalized muscle weakness, wrist arthralgia associated with edema, mobility limitation, morning stiffness and subsequent pain in MCP, PIP joints, knees, ankles and shoulders, in addition to fever of daily morning predominance, without rash, hair loss with areas of alopecia, nail loss and appearance of skin lesions in extensor areas of the MCP, PIP joints, elbows, chin and malar surface, described as erythematous scaly plaques, fever, epistaxis with findings of nasal ulcers and hematochezia. During hospitalization, diseases such as SLE (normal renal function, normal C3 and C4, negative antiphospholipid antibodies ANA, ENA) and systemic sclerosis (negative anti-SCL-70 and negative anti-centromere antibodies) were ruled out. Among the diagnostic hypotheses, a probable inflammatory myopathy of the dermatomyositis type was considered, fulfilling the Bohan and Peter criteria, by findings in the skin, generalized symmetric muscle weakness, electromyography + neuroconduction with myopathic pattern and magnetic resonance imaging that reported inflammatory-type myositis. However, muscle enzymes (total CK, LDH, TGO, TGP, aldolase) showed normal results and the muscle biopsy was negative. The patient was being treated with prednisolone 20 mg and azathioprine 50 mg indicated in the outpatient clinic, in combination with physical therapy. Screening for Pompe disease was performed, which was negative, and a second biopsy of the left semitendinosus muscle was requested, reporting nonspecific atrophy to be established by immunoperoxidase markers, which could not be performed due to non-authorization of his health insurance entity (in Spanish, EPS).

During hospitalization in September 2019, the clinical condition of the patient deteriorated, presenting tachycardia of 120 bpm and heart sounds that impressed pericardial friction rub. Laboratory studies were updated (Table 1) reporting leukocytopenia, lymphopenia, neutropenia, microcytic-normochromic anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated transaminases, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, IgG, as well as positive rheumatoid factor at a low titer. (Table 1). The echocardiogram reported a normal-sized left ventricle, normal global and segmental systolic function, ejection fraction: 60%, trivial mitral and tricuspid insufficiency, aortic valve with normal appearance and function, normal-sized right chambers, moderate to severe pericardial effusion, without hemodynamic repercussion. The total abdominal ultrasound showed a focal hepatic lesion that, due to its sonographic characteristics, suggested an hemangioma as the first possibility, and the chest computed tomography reported mediastinal lymphadenopathies, hepatosplenomegaly, and severe hypodense pericardial effusion. With these findings, it was considered that the patient met Parodi criteria for the diagnosis of MAS (Table 2), supported by: fever >38 °C, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenias in >2 cell lines, Hb < 9 g/dL, increased transaminases, hyperferritinemia, hemorrhagic manifestations and confirmation by BMA, which revealed macrophages phagocytizing hematopoietic cells (Fig. 1). In the intrahospital management, protective isolation, broad antibiotic and antifungal scheme, pulses of methylprednisolone 500 mg IV during 3 consecutive days followed by oral prednisone at a dose of 1 mg/kg/day max. 60 mg/day in combination with IgG at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day for 4 consecutive days were indicated, presenting a favorable clinical evolution. Later, the patient was evaluated by Hematology, who suspected an associated lymphoproliferative syndrome, and suggested to transfer him to an oncology center, where he died a few days later.

DiscussionHaemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis encompass a heterogeneous group of diseases that can occur at any age. The genetic or primary form manifests itself before the first year of life and includes known genetic defects, for example, perforin, and unknown genetic defects, immunological deficiencies such as Chediak-Higashi syndrome, Griscelli syndrome, lymphoproliferative syndrome linked to the X chromosome, and the acquired or secondary form, which can be seen in any age group associated with infectious, endogenous, oncologic, rheumatologic or immunological processes.9 The MAS is part of the acquired haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and it constitutes a potentially lethal disease, with difficulty in its identification and lack of consensus regarding its management.

We describe a series of cases of patients with a diagnosis of MAS classified by the Parodi criteria (Table 2), which have a sensitivity of 92.1% and a specificity of 90.9%. The simultaneous presence of at least one clinical criterion and at least 2 laboratory criteria is required for the diagnosis. Bone marrow biopsy could be necessary only in doubtful cases, which is an advantage of those criteria regarding other classification criteria proposed for haemophagocytic lymphohystiocitosis.10

Our patients fulfilled more than 5 criteria and also presented different underlying rheumatological diseases, among other associated conditions. It is important to highlight that, although MAS is found mainly as a complication of SLE, juvenile idiopathic arthritis and Still's disease, it is also possible to find it in other rheumatological diseases and that its appearance can be triggered by multiple causes, such as infectious conditions and use of medications, or due to neoplastic processes, among others. However, in many cases it is not possible to identify with certainty the associated etiological agent, because the acuteness of the clinical picture captures the attention of the clinician, ignoring that the management of these triggers is a fundamental component of its treatment. Egües Dubuc et al. described a series of 13 clinical cases of MAS secondary to autoimmune, hematological, infectious and oncological diseases, finding the symptom of fever as the only criterion they have in common. Splenomegaly or hepatomegaly was present in 12/13 patients studied.11

MAS is potentially lethal and its maximum manifestations can appear acutely, quickly leading to the onset of multiple organ failure that requires admission to an ICU, being reported mortality rates of 8–24% in cases associated with rheumatic events or infections and being higher when it is accompanied by malignancy. Aggravating factors in these patients include the presence of associated neutropenia, which is rare in the natural history of MAS, where the granular lines are not usually altered, and the appearance of opportunistic infections, which not only worsens the patient's prognosis, but also makes management difficult. It is imperative, then, to emphasize the importance of considering this syndrome in rheumatological patients, since it is usually an underdiagnosed entity, mainly due to lack of knowledge and to the lack of specific markers for the disease.

The therapeutic objective is based on stopping the inflammatory process. Since there are no controlled studies for the treatment of MAS, the management is based on empirical experience, the main axis being the use of high-dose parenteral glucocorticoids, mainly methylprednisolone pulse therapy for 3 consecutive days followed by oral prednisone. In cases that are not controlled with glucocorticoids, an association is made with an immunosuppressive therapy such as cyclosporine A (2–7 mg/kg/day)12. The use of cyclophosphamide, immunoglobulins (Ig), plasmapheresis, and etoposide as initial therapy has had conflicting results. However, it should be mentioned that the use of IV Ig in our patients, in combination with the use of corticosteroids, showed beneficial results, presenting a favorable clinical evolution with subsequent remission of symptoms.

In cases of malignancy, a specific treatment for the type of neoplasm should be followed, using etoposide as part of the regimen or rituximab in cases of lymphoma13. If it is due to an infection, the corresponding specific treatment should be followed. If the MAS is refractory to any of the aforementioned schemes or if EBV is the causative agent, the treatment protocol for haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis is useful13,14. Anakinra and infliximab may be beneficial in these refractory cases, and the use of IV Ig and rituximab has shown good results in the presence of EBV, cytomegalovirus, and in patients with MAS secondary to SLE.

ConclusionMAS is a potentially lethal entity, which can lead to acute multiple organ failure and it is a complication of some rheumatological diseases, in the presence of triggers, which mainly occurs with high fever, hepatosplenomegaly, neurological and hemorrhagic manifestations and laboratory alterations. Although it does not present easily identifiable parameters for its diagnosis, it must be considered and studied in patients with risk factors and rheumatologic disease in order to reduce the risk of mortality and promote its knowledge and management among clinicians.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThere is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Saldarriaga Rivera LM, Sánchez-Ramírez N, Rodríguez-Conde L, Tejedor-Restrepo DP. Síndrome de activación macrofágica como desenlace de enfermedades reumatológicas: reporte de 4 casos. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2020;28:221–226.