Telemedicine, defined as the provision of remote health services by health professionals using Information and Communication Technologies, has been adopted in healthcare in Colombia.

ObjectiveTo establish recommendations for the implementation and management of telemedicine in clinical practice for rheumatological diseases in Colombia

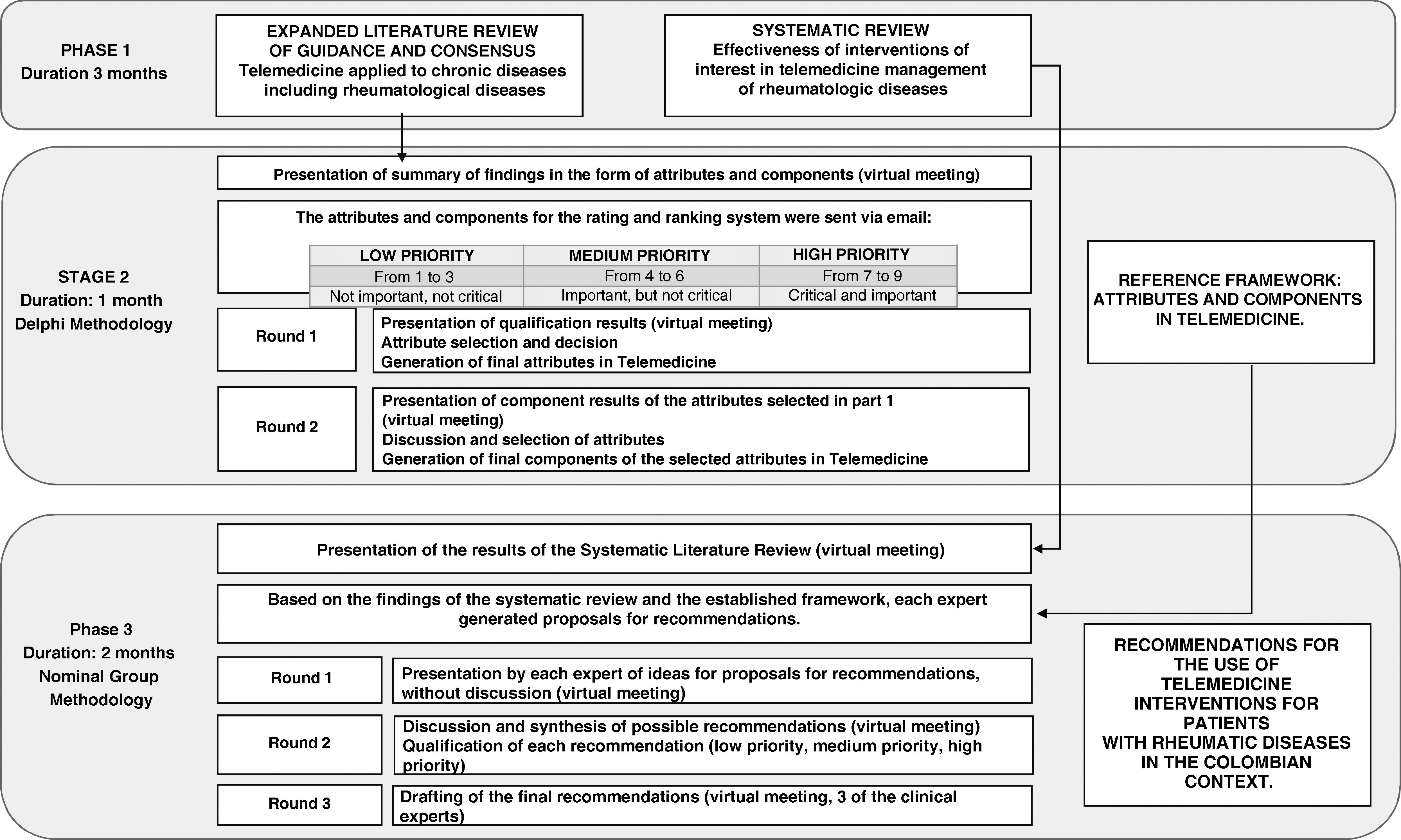

Materials and methodsThe recommendations were made in 3 phases. Phase 1 was based on an extended review and a systematic review of the literature. Phase 2 consisted of the selection of attributes and components based on the extended review to delimit the framework of the recommendations using the Delphi method. In phase 3, a group of experts, based on the systematic review, the selected attributes and components, and individual experience made recommendations through a nominal group.

ResultsThe framework of recommendations comprised 9 attributes and 26 components. A group of 7 rheumatologists in 4 cities of the country was formed. The nominal group drafted the final recommendations through 3 rounds according to the recommendations with a high priority rating.

ConclusionThis document contains recommendations for effective telemedicine healthcare for rheumatological diseases in Colombia. To establish effective telemedicine healthcare, it is necessary to evaluate different possible forms of care, the convenience of using telemedicine according to the clinical-cultural and sociodemographic profile of the patient, the access and implementation capacity of the different technological tools, and the exhaustive analysis of the barriers and facilitators to its adoption.

La telemedicina, definida como la provisión de servicios de salud a distancia por profesionales de la salud que usan tecnologías de la información y la comunicación, ha sido adoptada como modalidad de atención en Colombia.

ObjetivosGenerar recomendaciones para la implementación y el manejo de telemedicina en la práctica clínica para enfermedades reumatológicas en Colombia.

Materiales y métodosLas recomendaciones se establecieron en 3 fases. La fase 1 consistió en una revisión ampliada y una revisión sistemática de la literatura. En la fase 2 se seleccionaron atributos y componentes basados en la revisión ampliada para delimitar el marco de las recomendaciones utilizando metodología Delphi. En la fase 3, un grupo de expertos, de acuerdo con la revisión sistemática, los atributos y componentes seleccionados y la experiencia individual hizo las recomendaciones mediante un grupo nominal.

ResultadosEl marco de recomendaciones estuvo constituido con 9 atributos y 26 componentes. Se conformó un grupo de 7 reumatólogos en 4 ciudades del país. El grupo nominal, por medio de 3 rondas, redactó las recomendaciones definitivas, considerando aquellas recomendaciones con calificación prioridad alta.

ConclusionesEste documento contiene recomendaciones para una efectiva atención de telemedicina para enfermedades reumatológicas en Colombia. A fin de establecer una atención efectiva en telemedicina, es necesario evaluar las diferentes posibles formas de atención, la conveniencia del uso de telemedicina de acuerdo con el perfil clínico-cultural y sociodemográfico del paciente, el acceso y la capacidad de implementación de las diferentes herramientas tecnológicas y el análisis exhaustivo de las barreras y los facilitadores en su adopción.

Telemedicine, a term used since 1970,1 is a discipline that involves the use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) to provide medical services remotely. It is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as: «…The delivery of health services, where distance is a critical factor, by all healthcare professionals using ICT for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of disease and injury, research, and evaluation, and for the continuing education of healthcare providers, all to promote the health of individuals and their communities… ».2

In Colombia, telemedicine has been used for more than two decades in different specialties such as internal medicine, pediatrics, psychiatry, dermatology, cardiology, and radiology, among others.3 In this context, a broad regulatory framework has been created specifically for the provision of telemedicine services as a component of telehealth, which is defined, according to the guidelines of Colombian law 1419 of 2010, as follows: «… the provision of health services at a distance in the components of promotion, prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation by health professionals using ICTs, which allow them to exchange data to facilitate access and timeliness in the provision of services to the population with limitations of supply, access to services, or both in their geographical area …».

In rheumatic patients, the use of telemedicine as a healthcare model has mitigated the difficulties of access for the active population living in remote rural areas, as well as the mobility limitations that affect some patients and the limited availability of rheumatologists, due to the limited number of specialists available in the country and also due to the centralization of human resources in large cities.4–6 Operationally, telemedicine has been broadly grouped into synchronous interaction (real-time communication between the two locations), asynchronous interaction (real-time messaging between the parties), and remote monitoring (sending data from the patient to a database for later review).5,7

With the health emergency triggered by the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19), telerheumatology was adopted in many cases as the only means of care available to patients, exponentially accelerating its implementation.6,7 This led to the establishment of guidelines and recommendations for its use, such as the recommendations issued by the American College of Rheumatology, which highlight the use of telehealth as a care strategy for the management of rheumatic disease in adult patients during the COVID-19 pandemic.7,8

In Colombia, the obligatory social distancing, together with the socio-demographic characteristics of the population and the human resources in health, consolidated the need to parameterize and expand the practice of telerheumatology. One of the published experiences9 describes 1905 patients, seen between August 2017 and March 2020 under the modality of synchronous telemedicine, with a total of 4864 consultations, which were carried out with a rheumatologist physician at the reception site, as well as a general practitioner in charge of examining patients at the place of origin of the consultation, in most cases. The main diagnoses of the consultation were rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthrosis, joint pain, myalgia, and systemic lupus erythematosus, diagnoses of care similar to those reported by two systematic reviews published in 2017,5,10 in which rheumatoid arthritis stands out as the main diagnosis. There is also local experience with telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic, as described by Santos et al.11 regarding the transition from an outpatient service to a telemedicine service in a cohort of 3503 patients with rheumatoid arthritis in a center in Bogotá.11 Both the experience in the country and the published reviews highlight the importance of structured care and rigorous research to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telerheumatology, describing aspects such as the impact of different types of telemedicine on rheumatology patients, strategies for accurate diagnosis, the effectiveness of monitoring, and use of new technologies in rheumatology, among others.

Most authors agree that telemedicine represents an option for certain patient populations with rheumatic diseases; there is also a consensus that telerheumatology does not yet have a comprehensive standard or practice guideline established for its appropriate and effective implementation, due to the heterogeneity of current studies, the availability of country-specific technologies, the costs of implementation, the level of patient education, and the requirement for an interdisciplinary team.5,6,9,12,13 In addition to researching the efficacy and safety of telemedical interventions, decision-makers must establish specific rules on how telemedicine should be used to provide the best, most efficient, and safest possible care for the rheumatology patient. Among the minimums to be established are: data security, operating protocols, telemedicine documentation, and informed consent, among others. Therefore, this expert group is expected to generate a series of recommendations to support the definition of general standards for good practice in the provision of healthcare services to patients with these medical conditions.

Materials and methodsThe choice of method was based on the need to combine scientific evidence and the collective judgment of experts, taking into account the heterogeneity of the scientific literature available in telemedicine and the characteristics of the rheumatic patient in the country.14 The methodology consisted of 3 phases (Fig. 1):

Phase 1: an extended literature review of guidelines, consensus, and systematic reviews published between 2015 and 2020, to learn about recommendations made in telemedicine applied to chronic diseases. The sources consisted of the databases Medline via OVID, Embase, and LILACS, and in the case of guidelines, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, the World Health Organization (WHO), the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network, and the National Guideline Clearinghouse. The search terms included “telemedicine” and “teleconsultation”.

A systematic review of the literature was conducted to determine the effectiveness of telemedicine in the management of rheumatological diseases. Medline, Embase, and the Cochrane database of systematic reviews were searched. GreyNet databases and a snowball search were used for the grey literature. Search terms included “telemedicine”, “remote consultation”, “teleconsultation”, “telehome”, “telediagnosis”, “video consultation for telemedicine and rheumatology”, “rheumatoid arthritis”, “rheumatic diseases,” “connective tissue diseases, and autoimmune diseases”, among other search terms for rheumatological conditions, and MeSH or Emtree terms were used, as well as related terms combined with Boolean operators. Three authors independently selected systematic reviews, randomized or non-randomized clinical studies in patients with autoimmune or inflammatory rheumatic diseases, in which telemedicine was compared to standard care. Efficacy was measured in terms of disease activity, quality of life, and functional activity. Additionally, patient satisfaction was measured. The risk of bias was assessed with the Cochrane Collaboration tool for randomized studies and AMSTAR II for systematic reviews. The results are the subject of a separate publication, approved by Telemedicine and e-Health, for publication “Manuscript ID TMJ-2022-0098.R1”.

Phase 2: Using the Delphi methodology and based on the results obtained in the extended literature search, a qualitative synthesis of the information was carried out, as a result of which concepts were formulated in the form of “statements,” called attributes, and components, which were presented in a virtual meeting and sent by e-mail to 7 expert rheumatologists, to be qualified. Each statement was rated from 1 to 9, according to the level of priority. In the first session, attributes rated as high priority were selected, and those with equal ratings of medium priority and high priority were submitted for discussion; attributes with any score of low priority, or medium priority above 60% agreement, were not included in the discussion. In the second session, the results of the components of the selected attributes were presented: the components with more than 50% agreement as a high priority were selected, while the components with a high priority of 50% were discussed and the lower percentages were excluded.

Phase 3: A group of seven national clinical experts was formed and convened based on their experience in healthcare and telemedicine care, who, based on the systematic literature review, the reference framework, and their individual expertise, drew up the recommendations by consensus using the nominal group methodology. A group of seven national clinical experts was formed and convened based on their experience in healthcare and telemedicine care, who, based on the systematic literature review, the reference framework, and their individual expertise, drew up the recommendations by consensus using the nominal group methodology. In a second session, the different proposals presented were discussed, and a synthesis of possible recommendations was obtained, which were rated from 1 to 9, according to the level of priority. In a final session, the final recommendations were drafted according to the recommendations with a high priority rating.

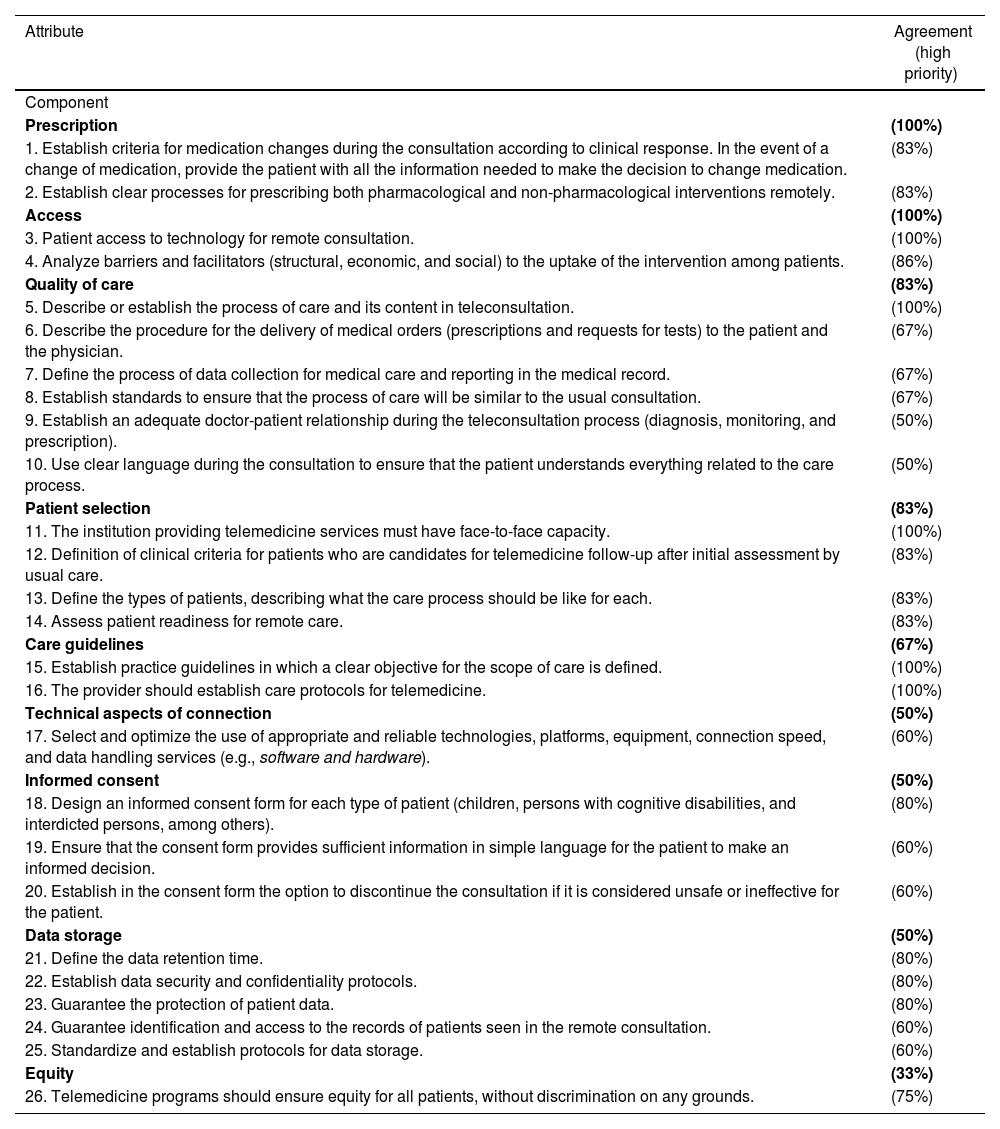

ResultsThe expert group consisted of 7 rheumatologists from 4 cities in Colombia (Cali, Medellín, Barranquilla, and Bogotá), with an average time of experience as rheumatologists of 8.5 years (±2.3). Table 1 summarizes the attributes and Components that served as a guideline for the development of the recommendations.

Framework: attributes and components as a guideline for the development of rheumatology telemedicine recommendations for the Colombian context.

| Attribute | Agreement (high priority) |

|---|---|

| Component | |

| Prescription | (100%) |

| 1. Establish criteria for medication changes during the consultation according to clinical response. In the event of a change of medication, provide the patient with all the information needed to make the decision to change medication. | (83%) |

| 2. Establish clear processes for prescribing both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions remotely. | (83%) |

| Access | (100%) |

| 3. Patient access to technology for remote consultation. | (100%) |

| 4. Analyze barriers and facilitators (structural, economic, and social) to the uptake of the intervention among patients. | (86%) |

| Quality of care | (83%) |

| 5. Describe or establish the process of care and its content in teleconsultation. | (100%) |

| 6. Describe the procedure for the delivery of medical orders (prescriptions and requests for tests) to the patient and the physician. | (67%) |

| 7. Define the process of data collection for medical care and reporting in the medical record. | (67%) |

| 8. Establish standards to ensure that the process of care will be similar to the usual consultation. | (67%) |

| 9. Establish an adequate doctor-patient relationship during the teleconsultation process (diagnosis, monitoring, and prescription). | (50%) |

| 10. Use clear language during the consultation to ensure that the patient understands everything related to the care process. | (50%) |

| Patient selection | (83%) |

| 11. The institution providing telemedicine services must have face-to-face capacity. | (100%) |

| 12. Definition of clinical criteria for patients who are candidates for telemedicine follow-up after initial assessment by usual care. | (83%) |

| 13. Define the types of patients, describing what the care process should be like for each. | (83%) |

| 14. Assess patient readiness for remote care. | (83%) |

| Care guidelines | (67%) |

| 15. Establish practice guidelines in which a clear objective for the scope of care is defined. | (100%) |

| 16. The provider should establish care protocols for telemedicine. | (100%) |

| Technical aspects of connection | (50%) |

| 17. Select and optimize the use of appropriate and reliable technologies, platforms, equipment, connection speed, and data handling services (e.g., software and hardware). | (60%) |

| Informed consent | (50%) |

| 18. Design an informed consent form for each type of patient (children, persons with cognitive disabilities, and interdicted persons, among others). | (80%) |

| 19. Ensure that the consent form provides sufficient information in simple language for the patient to make an informed decision. | (60%) |

| 20. Establish in the consent form the option to discontinue the consultation if it is considered unsafe or ineffective for the patient. | (60%) |

| Data storage | (50%) |

| 21. Define the data retention time. | (80%) |

| 22. Establish data security and confidentiality protocols. | (80%) |

| 23. Guarantee the protection of patient data. | (80%) |

| 24. Guarantee identification and access to the records of patients seen in the remote consultation. | (60%) |

| 25. Standardize and establish protocols for data storage. | (60%) |

| Equity | (33%) |

| 26. Telemedicine programs should ensure equity for all patients, without discrimination on any grounds. | (75%) |

Prescriptions made through telemedicine services should follow the same guidelines as face-to-face care.

Initiation or modification of treatment should be made only at the discretion of the treating rheumatologist, based on the information collected at the consultation. If the physician feels that he or she does not have sufficient tools to make treatment adjustments, he or she should be able to refer the patient for a face-to-face assessment to make an optimal therapeutic decision.15

Develop communication channels in which the patient receives the prescriptions generated through telemedicine services.15

Component 2Comply with relevant national guidelines before deciding to prescribe a medicine.

AccessComponent 3The service provider has the responsibility to ensure that his or her services are affordable and inclusive for all those who need them.15 If the patient does not meet the characteristics of access, understanding and facility to access any of the categories in telemedicine, the patient must be assessed in person, either intra- or extra-mural.

It is recommended that telemedicine healthcare be affordable to as many individuals as possible. It should be easily accessible using modern applications and browsers,16 including the availability of access for people with disabilities, among others.

The healthcare provider should make clear what services are available and not available online (laboratory tests, controlled drug administration, etc.). In addition, it should make patients aware of emergencies in which rapid access to intramural care services is required.

Patients who do not speak Spanish (e.g., indigenous patients) or are illiterate cannot be excluded from access to telemedicine care. The service provider must be able to identify them and make the necessary adjustments to accommodate them.

Patients with mental or cognitive disabilities require the accompaniment of their parents or caregivers in the telemedicine consultation. In this way, they can be involved in care planning, treatment, and patient management.

Component 4Examine barriers and facilitators to the uptake of interventions, i.e., assess the characteristics of individual or population subgroups that present different challenges to accessing health services. Socio-economic aspects, geographical location, and education, as well as socio-cultural and demographic factors, need to be considered. Discussion of these limitations is a determining factor in establishing in which groups telemedicine care is appropriate.

Quality of careComponent 5The recording of the medical history in the consultation room must follow the valid applicable regulations (Resolution 1995 of 1999, Law 2015 of 2020, Resolution 866 of 2021) that are handled in the face-to-face consultation room.

If the telemedicine consultation is carried out on a platform other than the institutional medical record, the platform used during the consultation should be indicated.

Assess whether the quality and completeness of clinical information and images, examinations, and diagnostic tests provided by the patient are sufficient for consultation by this modality. If insufficient, request additional information from the patient or refer for a face-to-face consultation.17–19

Record the names of those attending the telemedicine consultation (family members or caregivers), and any technical difficulties that may have impacted the physician's ability to fulfill his or her duty of care.

Confirm that the patient or caregiver is informed of the agreed-upon processes for implementing the management plan.

All documentation related to telemedicine, including referrals, consultation notes, and images, should be retained for the period required for medical records according to national regulations.

Referral to other specialties or healthcare professionals is an important part of telemedicine; therefore, it must be available when required for the patient.

Component 6Before the consultation, it is necessary to arrange with the patient how the medical orders are to be delivered, in case the patient does not have the technological means to access the documents. During the consultation, in addition to generating the relevant medical orders, the patient should be given a clear explanation of the actions to be taken during the consultation.20

When a patient is referred to the Rheumatology Service, the interaction with the referring physician should include the following information: agreed management plan, required follow-up, and red flags.

Initiate the referral process to the corresponding specialty(ies) or to the necessary care center in case of a diagnosis of severe disease (rheumatic, non-rheumatic, or requiring the assistance of other specialties in addition to rheumatology) for the care of the pathology.

Component 7Record the results and interpretation of diagnostic tests according to the applicable regulations in force.

Consider the limitations of the healthcare professional's abilities to perform consultations using remote methods, e.g., assessment of signs and symptoms or behavioral disturbances by telephone consultation.

Take into account the difficulties that may be encountered in assessing service users with vulnerabilities (e.g., people with mental illness or disorders, adults with disabilities, people with complex medical histories, and polymedicated people). Consideration should also be given to circumstances where it may be necessary to deliver bad news or deal with complex ethical situations. In all of the above situations, it is recommended that patients be redirected for a face-to-face consultation.

Minor patients should always be accompanied by their parents or caregivers during the consultation.

When prescribing remotely, prescribers should ensure that they can perform an adequate and reliable assessment of the patient without compromising patient safety.

In certain circumstances, it is necessary to assess the likelihood that a physical examination may be required, either at the initial consultation or at a follow-up appointment; in such a case, arrangements should be made for the face-to-face consultation.

Healthcare professionals should be aware of their skills and limitations and work only within their competencies. They should seek advice from experienced colleagues when required, due to the complexity of the patient or the particular conditions of the patient. In cases of doubt about the syndromic diagnosis or in the presence of a case that is difficult to manage, a referral for face-to-face consultation is recommended.

Technology providers must implement security systems and mitigate the risks associated with remote queries (confidentiality, loss of information, etc.); they must also be accountable for the performance of their data systems and for maintaining continuous improvement of the quality of their data systems, ensuring the availability of protection policies for all staff.

Develop internal audit processes to monitor the quality of care, operational processes, financial processes, and systems used in telemedicine patient care to identify areas for improvement and take the necessary steps to optimize the service.

Patients or their caregivers should have the opportunity to ask questions and clarify any concerns they may have regarding their prescription at any point in the care process, including contact details that patients can use after the initial consultation.21

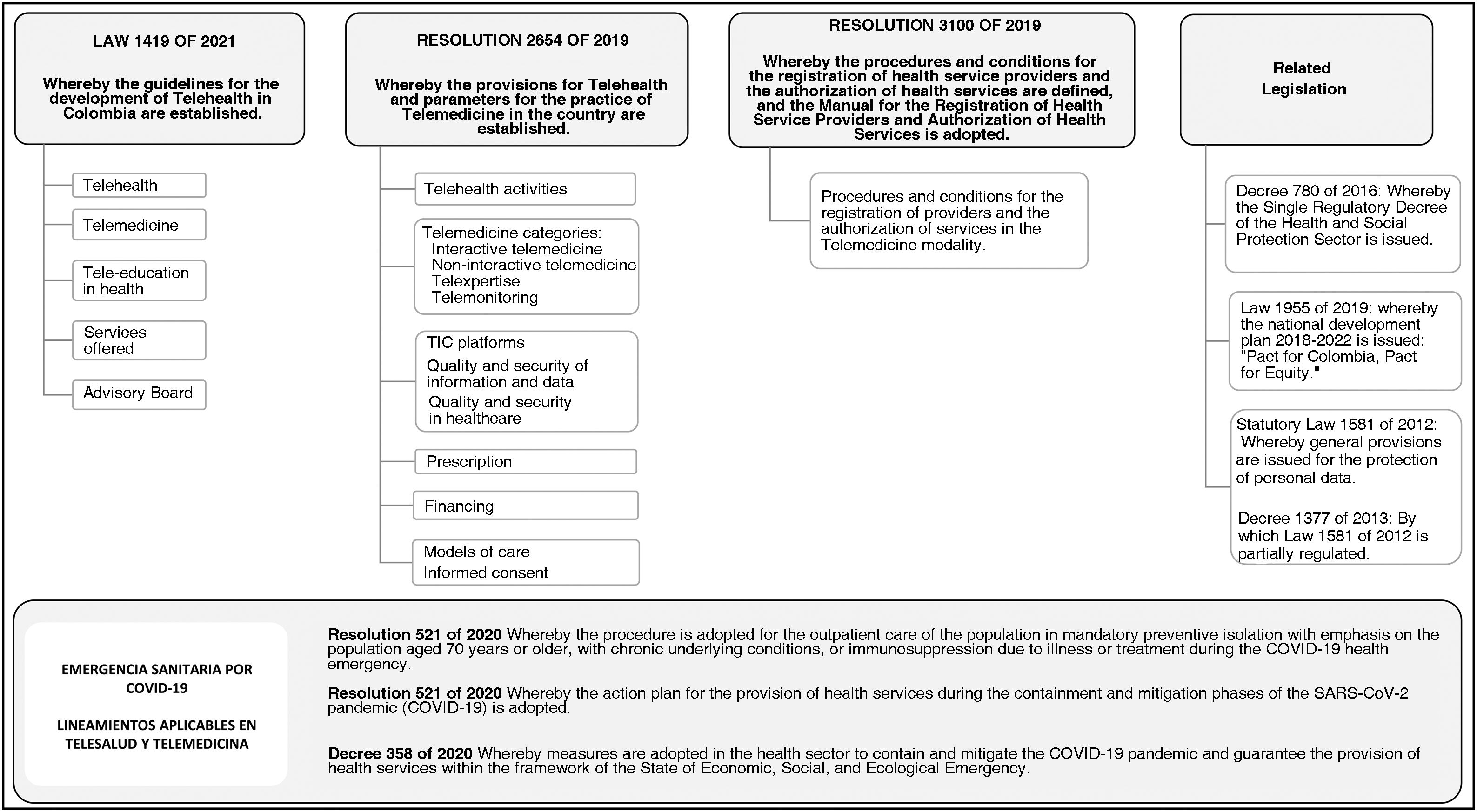

Component 8The current regulatory framework and amending regulations in telehealth and telemedicine must be complied with (Fig. 2), taking into account the adoption of reasonable measures to protect patient privacy, the privacy of patient medical records, and privacy reporting.

To determine whether the technical and socio-technical factors of videoconferencing interaction are of sufficient quality for a telemedicine consultation.

Component 9Healthcare staff providing remote consultation should understand and promote compassionate, respectful, and empathetic behavior. In this context, communication channels with the patient or caregiver should be optimized.

Healthcare professionals should be available to discuss care and treatment options with the patient, if necessary. The discussion should include health, social, and emotional needs. Support and reassurance are needed to ensure that the patient understands the risks and benefits associated with their choices and to enable them to make informed decisions about their care and treatme.18

Component 10Professionals providing services through telemedicine should offer individualized care using appropriate, clear, and simple language that takes into account the patient's cultural level. In this way, care and treatment will be person-centered and focused on assessing the patient's needs and preferences.

Patient selectionComponent 11Ensure that the pathway between face-to-face (intramural and extramural) and telemedicine or telehealth services is well supported and does not put the service user at a disadvantage if they need to move between the two types of services.

Component 12Consider telemedicine as an alternative when face-to-face consultation is not feasible for the patient. Face-to-face consultation will always be preferable.

Consider clinical judgment in the selection of patients for the telemedicine modality. Evaluate the possibility of splitting the telemedicine consultation into a face-to-face and a remote proportion when physical examination is indispensable; in any case, when a face-to-face visit is required at the physician's discretion, it should be recorded in the telemedicine consultation.19

Telemedicine consultation is appropriate when: a) patients have a clinical need or for simple treatment requirements; b) physicians have access to medical records; c) physicians can provide information and explain what is needed in relation to treatment options, by telephone, internet, or video call; d) the patient does not need to be examined; e) the patient has the capacity to decide about their treatment; f) patients do not have severe communication disabilities.19,22

The doctor assessing the patient for the first time via telemedicine may request the examinations he or she considers relevant to focus the case and decide whether the second visit should be face-to-face, in the case of requiring a physical examination or in the case of a patient with difficulties to be seen via telemedicine.

In the event of any difficulty in the patient's care, as in the face-to-face consultation, the assistance of a third party may be required to facilitate communication.

Patient selection according to clinical factors and communication skills is recommended to establish the complexity and modality of the consultation.22

Component 13It is recommended that the decision for telemedicine be defined according to the following criteria: a) the clinician is able to make a definitive diagnosis; b) providing comfort and expertise with the clinician; c) the need for clinical examinations; d) clinical factors such as clinical status, type of consultation, and complexity of the consultation; e) whether the institution where the clinician works meets the criteria to provide telemedicine services; f) factors such as continuity of treatment and existing patient-physician relationship; g) practical factors such as availability of specialists, local clinical equipment, and technology; h) willingness to travel, patients' families, and cultural background.

Different categories of telemedicine should be available, according to the clinical conditions of each patient, the scope of interventions needed, and the capacity to use telemedicine tools.

Component 14In the pre-intervention approach to telemedicine, it should be investigated whether the patient has the minimum technological means available to carry out the intervention to be performed appropriately. Each center must establish the minimum necessary for each specific intervention.

It is recommended that an informative contact regarding telemedicine be made prior to initiating this type of care.

Care guidelinesComponent 15Each center providing telemedicine activities should establish management guidelines based on national and institutional guidelines for the treatment of different diseases. To do so, it should take into account national regulations regarding telehealth activities and strictly monitor adherence to the guidelines to establish improvement plans, if required.

Whenever possible, diagnostic interventions should be supported by high-quality evidence. Where this is lacking, health professionals will use their professional judgement, experience, and expertise to establish an accurate diagnosis.22 Thus, they should continually consider the likelihood of changing clinical patterns related to telemedicine, based on new findings in research and technological development.

Healthcare providers must ensure compliance with all laws, regulations, and security codes relevant to the technological and technical security of information handled in telemedicine.23

Where guidelines, tools,24 statements, or standards from a professional organization, government or scientific society25 exist, they will be reviewed and incorporated into practice whenever safe, contemporary and feasible.

Component 16Healthcare professionals will determine the suitability of telemedicine use and its categories on a case-by-case basis, whether or not a telemedicine visit is indicated, and in which cases a face-to-face consultation is required for clinical assessment of the patient.19,22 This will be documented in the medical record, in compliance with the appropriate standards for assessing the patient.

Healthcare professionals will be responsible for maintaining clinical practice guidelines to guide the delivery of care in the telemedicine environment, bearing in mind that some modifications may be necessary to adapt to specific circumstances.22

Technical aspects of connectionComponent 17Healthcare providers should ensure that the website is easy to navigate, through regular reviews and feedback from service users.15 In addition, according to current regulatory guidelines, additional forms of communication should be considered in areas where internet access or computer use is limited.

Digital support should be available to all users on the website so that they can get an explanation or additional information if required. Help icons should be easy to identify, clear, and consistent. The provider should have a mechanism for reviewing their use, so that it can identify areas requiring revision and ensure that information is kept up to date to meet the needs of service users.

The provider should actively seek feedback from users about their experience using online services, including how the care and treatment have met their needs and suggestions for improvement. It is recommended that satisfaction surveys be implemented to generate quality indicators for the telemedicine service.

Clearly establish the availability of physical infrastructure to support technology operations at the site where service delivery will originate, including electricity, energy access, and connectivity in the local context, among others.20,26 It is also necessary to assess the suitability of patients for telemedicine care, using pre-established checklists with the minimum requirements for adequate connection.

The healthcare professional should verify whether the technical and socio-technical factors of videoconferencing interaction are of sufficient quality to conduct a telerheumatology consultation.17

Providers should, as far as possible, offer the patient different software alternatives for telemedicine, which should have the possibility to be used on different devices (computers, tablets, mobile phones, etc.), to facilitate patient care.17,19

It is recommended that the provider or patient be able to use link testing tools (e.g., bandwidth testing) to verify bandwidth connectivity prior to care to ensure quality of service. The use of wired connections should be considered when available (e.g., ethernet).

Telemedicine healthcare interventions should not be considered to be of lower quality than face-to-face interventions.23

Enable videoconferencing software to adapt to changing bandwidth environments without losing connections.

Informed consentComponent 18In the case of interactive telemedicine, it is recommended that participants are validated before the session begins and a record of care is made.

Prior to the appointment, the advantages and disadvantages of the telemedicine modality of care should be explained to the patient, and informed consent should be requested so that the patient has the possibility to disagree and request face-to-face care if he or she wishes to do so.17

The consent should contain all the principles required by the applicable regulations in force. In addition, it is suggested to detail: a) the telemedicine process and why this process helps the patient in their care; b) the medical information will only be based on the images and information provided; c) the points regarding risks and limitations; d) explain the difference in diagnostic accuracy between face-to-face consultation (intramural or extramural) and telemedicine; e) explain the difference in diagnostic accuracy between telemedicine and in-person consultation (intramural or extramural).15,17

Consent should be obtained prior to care by the telemedicine care manager, ensuring that the record is clearly identifiable, and that the information is accurately recorded, so that the process can proceed.17,19

Establish where there is a need for face-to-face consultation.

It is advisable, if possible, to be accompanied by a family member or companion if the patient expresses any doubts about the type of care.

Component 19Before receiving consent approval from patients, it must be ensured that the patient is aware of the different care options, any risks, and that they understand the proposal to which they are consenting.

Informed consent in healthcare means that the patient received clear and understandable information about his or her options so that he or she could make good decisions about his or her health and care.

Component 20Establish in the informed consent the possibility for the patient to withdraw if he or she considers the telemedicine consultation to be unsafe or ineffective.27

The development of guidelines for proper informed consent in telerheumatology should be promoted.

Data storageComponent 21The information obtained in the course of care must be stored according to legal provisions.

The storage of the telemedicine medical record shall be kept in the medical record as part of this document. This information shall be kept on file for the period of time required by the regulations in force.17

Component 22Establish medical record data security protocols and tools.20 Technology providers should verify that websites are secure and have essential cyber certification to protect against malware, hackers, and cyberattacks, according to applicable legislative guidelines.

Component 23Clinical records must be supported by auditing, management, planning, and monitoring. Institutions are responsible for monitoring the storage of records.

Ensure the protection of health data and records according to applicable local regulations.17 Clinicians must ensure the same level of confidentiality as in a face-to-face consultation.

If the clinician needs to request services from local providers, consideration should be given to how to send the information securely, including any follow-up or review.

Component 24The clinical consultation should record: the service performed by telemedicine, the category of telemedicine (specifying the use of smartphone devices, secure transmission, videoconferencing platforms, videoconferencing via a data network, etc.), the date and time of the consultation, and each healthcare member's responsibility for care management.

The telemedicine consultation, as well as the clinical image report, are part of the medical record and should be stored per patient or in a secure archive.

It is recommended that the institution establish the final disposition of the documentation shared by the patient.

Component 25Among the data storage considerations stipulated by regulations, it is suggested to highlight the following aspects: a) secure filing; b) no modification of images; c) mitigation of data loss; d) access control; e) encrypted images; f) image repository; g) storage in the computer cloud.

Telemedicine service providers require procedures for records management, meeting the requirements of legislation related to the use of private data.

EquityComponent 26The health service provider must guarantee equal access to telehealth services for all patients.15 In turn, the patient should be able to choose the modality of care (intramural, extramural, or telemedicine) in agreement with the treating physician.

The healthcare provider should ensure that the route between modalities of care allows the patient to move between the two services, if required, to ensure continuity of treatment and the required follow-up.

Content and user interface design should promote diversity and not discriminate against any protected characteristics.

Websites and applications should be user-friendly and not directly or indirectly discriminate against those with low levels of digital literacy. Telehealth interventions should include the promotion of digital literacy for both healthcare workers and patients.

Regulations related to patient care through telemedicine should be in line with the principle of equity, so that they are adapted to the conditions of patients and their possible limitations and guarantee access to the service without any discrimination.

ConclusionWith the advent of new information and communication technologies, the historical need for comprehensive healthcare coverage in distant regions of the country, as well as the social distancing imposed by COVID-19, has consolidated telemedicine as a modality of healthcare service delivery in Colombia.

At its peak of implementation and development, telemedicine as a component of telehealth has specific regulations and greater parameterization and expertise among the different health actors; however, there are still a variety of challenges to overcome in order to make it effective and accessible to the patients who require it, such as rheumatic patients. The development and publication of these recommendations is an effort to support the implementation and standardization of the use of telemedicine in the context of the care of patients with rheumatic diseases for healthcare professionals.

The recommendation for successful treatment of patients with rheumatological diseases includes ensuring that they have easy and direct access to care and specialists in different fields. Access to effective care is critical during the course of the disease, as it allows for early diagnosis, the initiation of treatment, and changes in disease management as the disease progresses. For telemedicine care to be effective, it is necessary to assess the different possible forms of care, the suitability of the use of telemedicine according to the clinical-cultural and socio-demographic profile of the patient, the access and implementation capacity of the different technological tools, and the exhaustive analysis of barriers and facilitators in the adaptation of such interventions. All in compliance with the relevant laws, regulations, and security codes to ensure the technological and technical security of the information handled in telemedicine.

The available scientific evidence supporting the recommendations relates to patients with rheumatological diseases treated by telemedicine, mostly at the international level, so the definitions and key points of the interventions were selected and adjusted according to the Colombian context. The recommendations provide key points for good clinical practice in telerheumatology, highlighting that the quality of care should be equal to that provided in face-to-face intervention; however, telemedicine is constantly being adapted and updated, which makes the recommendations applicable to the current Colombian environment, and further updates may be required thereafter.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest in the preparation of this paper.

FundingWork funded by Pfizer S.A.S.